|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 26

Grubstake to Grocery Store: Supplying the Klondike, 1897-1907

by Margaret Archibald

Conclusion: The Well-Appointed Ghost Town

After 1905 it was obvious that the Klondike valley was to be divided

among a few large corporate claim-owners whose technological and

financial manipulation of the hydraulic and dredging processes would

secure control of gold mining in the 20th century.1

Population declined, and for those who remained there was a growing

dependence on these large gold-mining companies for jobs — and, in

the case of the merchant, for sales.

By 1906 most claims were mining camps whose owners stocked goods from

Dawson wholesale firms to feed their employees.2 Needless to

say the system was a fine one for those wholesalers who could snap up

one of these contracts (usually one of the two surviving trade

corporations, the NC Company and the NAT&T Company) but many of the

smaller firms were forced to close. Even then, the price offered by the

gold companies was barely above cost, and the profits of those companies

which did manage to survive were minimal. This new existence as a

company town was itself short-lived, for in 19073 Guggenheim,

the backers of one of the largest of the gold companies, announced that

henceforth they would send their orders for provisions to the west

coast. From that point forward, commercial Dawson was destined to

continue as a shadow of its former active self.

But Dawson was an adamant ghost town and a reluctant has-been. While

most of her early courtiers had loved her and left her, ten years after

her prime she did retain a few sympathetic admirers. Among them was E.O.

Ellingsen, who appreciated her still for her antiquated glamour.

Ellingsen's craft was photography, and for his models he chose Dawson's

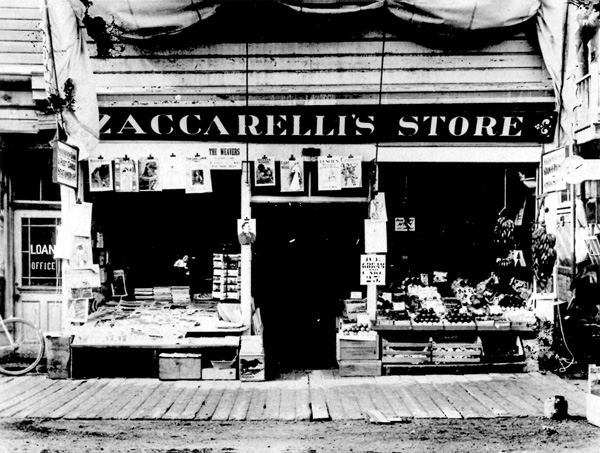

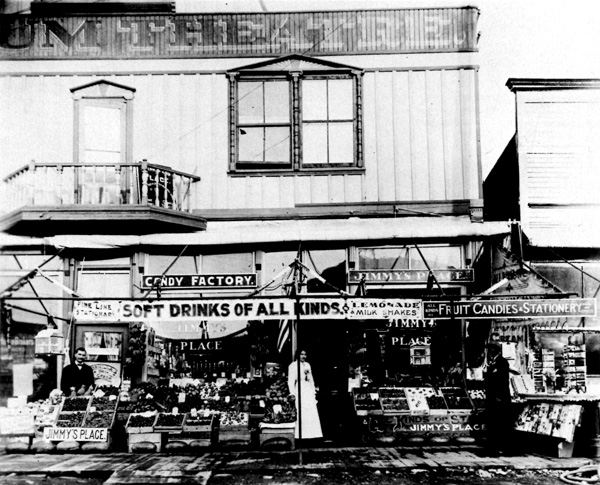

most elegant parlours, emporia and sidewalks. In three 1909 photographs

of some of the city's finer shops (the NC Company's, Zacarelli's and

Jimmy's palace of sweet fruits and stationery — see Figs. 39, 56, 58

and 59) Dawson appears as a young Edwardian lady, only slightly

overdressed for the occasion.

56 Jimmy's Place, Dawson (tobacco, stationery and confections), ca.

1913. Note the electric lighting.

(Public Archives Canada, C

21095.)

|

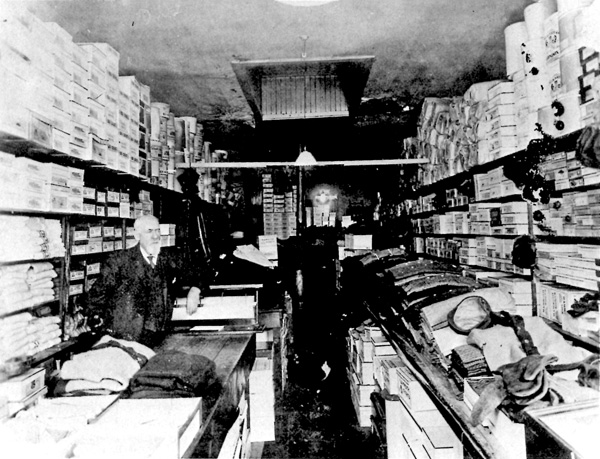

57 Daniel Kearney, a Dawson dry goods merchant, ca. 1905.

(Public

Archives Canada, C 16462.)

|

58 Zacccarelli's store in Dawson, ca. 1908. Photo by E.O. Ellingsen.

(Public Archives Canada, C 8121.)

|

59 Jimmy's Place, Dawson, ca. 1910. Photo by E.O. Ellingsen.

(Public

Archives Canada, C 8128.)

|

By that time, her riverfront façade was more rococo than ever.

While the elaborate effect of storefront finery was really no more

baroque than that found on King, Queen or Front streets in any other

Canadian city, there was something stilted about Dawson's streetscapes.

The original boom-town front — a matter of economy in times of

astronomical lumber prices — had been distorted beyond recognition

by the studied use of flourishes and curlicues.

Perhaps one had to see what lay behind that façade. While

Second and Third avenues had once been lively thoroughfares and still

did contain some thriving stores, the whole area was

on the verge of becoming a desert of secondhand shops & junk

yards. Some of the buildings were already vacant and the windows boarded

up. The secondhand shops were jammed with the refuse of the gold rush:

stoves, furniture, goldpans, sets of dishes, double-belled seltzer

bottles, old fur coats, lamps, jardiniers, cooking utensils, rubber

boots, hand organs, glassware, bric-a-brac silver, and beds, beds,

beds.4

One of the few general merchants to survive the heyday of the

specialized retailer was E.S. Strait, his specialty, auctioneering and

secondhand goods.5

By 1909, 11 grocers, 4 general merchants, 12 dealers in dry goods, 8

dealers in hardware, 4 secondhand traders and 4 fruit, candy and tobacco

sellers remained in town to supply the 2,000 inhabitants.

Amalgamation and consolidation continued. In 1912 the NAT&T

Company was forced to withdraw, leaving the NC Company as the final

winner of the retail monopoly, a position which the San Francisco firm

held in the Yukon until 1969. In that year the first of the great

Pacific northwestern trade monopolies withdrew from its last bastion of

retail sales, Whitehorse, just a little more than a century after its

incorporation as a sealing enterprise. The sale left Taylor and Drury as

the leading multi-purpose department store in Whitehorse. Founded upon a

partnership formed 71 years earlier on the trail of '98, Taylor and

Drury had worked from a keen sense of enterprise and an intuitive

knowledge of what the goldseeker would buy at any price. "Buying from

the downhearted and selling to the stouthearted:" the motto held true on

the trail, along the river and on the wharves. Later conditions,

however, called for a more rational and streamlined approach to

ordering, shipping and marketing. The decade following the gold-rush

demanded commercial skills of a different kind.

Hundreds of swappers, traders, pedlars and scowmen had swarmed over

the passes, surprised to find their much-sought gold in a form which was

crystallized, condensed, evaporated and tinned. Few of them outlasted

the great monopolies as did Taylor and Drury, but then longevity had not

been their goal. Their commercial careers had been for the most part

brief; a few were notable and many were nameless. In Dawson, the

permafrost has equalized their abandoned monuments. The false fronts sag

and the nearly illegible grey names no longer speak of proud

reputations. Lurching into the street, Strait's secondhand store still

proclaims its "tobaccos, furniture, crockery, clothing, tents, guns,

ammunition." Once there was a grocer and jobber who could declare, in

truth, that he could provide "anything from a needle to a

steamboat."6

|