|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 26

Grubstake to Grocery Store: Supplying the Klondike, 1897-1907

by Margaret Archibald

"Metropolitan Airs" — Dawson from 1899 to 1903

In his annual report for 1899 Superintendent A.B. Perry of the

North-West Mounted Police claimed to be

astonished to find so many substantial buildings, enormous

warehouses, fine shops, articles of costliest and finest description [in

Dawson] . . . The Yukon Council have provided sidewalks, bridges, graded

and drained streets, fire brigades, electric street lighting and many

other conveniences.1

In that same fall the Dawson Daily News declared proudly that

"substantial business blocks have taken the place of flimsy shacks and

neat frame dwellings have succeeded the log house. All this indicates a

belief in the permanency of Dawson as a mining centre."2 One

passing writer openly expressed his surprised reaction to the city's

appearance in 1903.

The first sensation experienced in Dawson was that of surprise at

the size and appearance of the town. With a population of about 7000,

with streets solidly built up for nearly a mile along the river, and

business extending back from the riverfront to Third Street; with graded

streets, water service and sidewalks and comfortable log and frame

storehouses and dwellings, the impression created is one of solidity and

permanence, which I venture to say is not generally entertained by those

who have not seen this metropolis of the Yukon.3

The self-confident view that Dawson wished to impress on the outside

world at the turn of the century was one of stability, prosperity and

progress, of rapid transition from a boisterous frontier boom town to a

fine Canadian centre of business and industry. Indeed, contemporary

journalistic reflections on the town during the period 1899-1903

radiated a booster-spirit aura, a feeling of civic pride in the orderly

change of both appearance and behaviour. When corroborated by

contemporary pictorial accounts of material changes and improvements,

the impression of metamorphosis seems justified indeed. Dawson did not

greet the 20th century with the shoddy boom town façade which

characterized it in 1898. The new façade was a finer, glossier

and more respectable one; it was more in keeping with that of a growing

business community in southern Canada (Figs. 28 and 29).

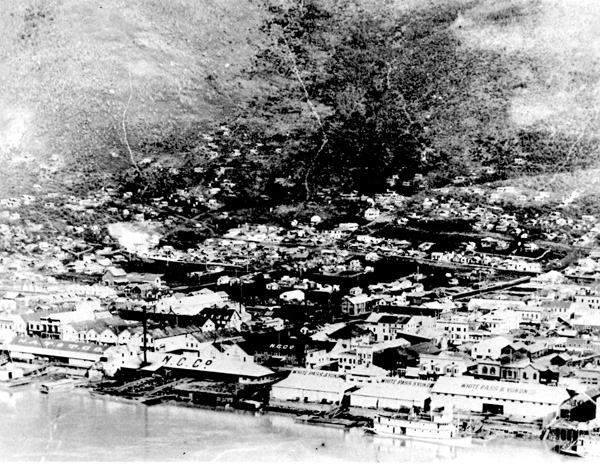

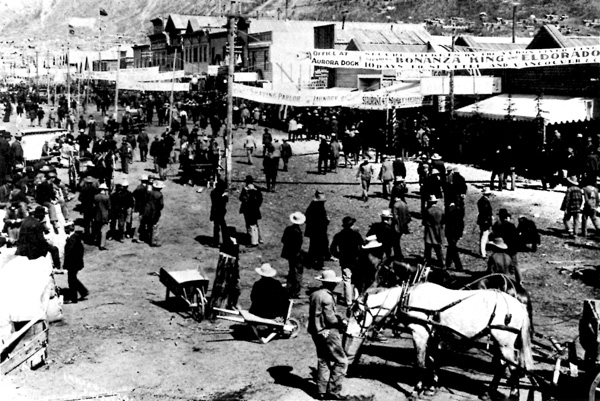

28 Bird's eye view of Dawson, showing docks, warehouses and stores

between King andd Queen streets, ca. 1902.

(Public Archives Canada, C 17015.)

|

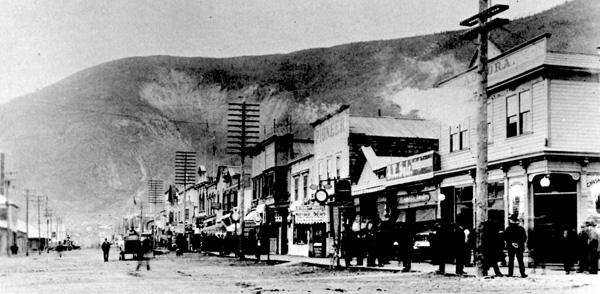

29 Northeast panorama of Dawson, ca. 1903. The main street to

the right of centre is King Street.

(Public Archives Canada, C 675.)

|

Six lumber mills operated in the town by 1899. By 1903 frame

buildings of two and three storeys had replaced log cabin structures in

the business section to such a degree that those log cabins remaining in

the city's core were singled out by one observer with a touch of

historical appreciation.4 In 1899 the first brick building

constructed entirely of local materials was erected on Third Street

between Third and Fourth avenues.5 It was a cold storage

warehouse for the Dawson Warehouse Company, and the building managed to

withstand the rigours of permafrost, the greatest hazard associated with

brick construction in the north. While the Dawson Daily News

enthusiastically heralded brick as the building material of the

future,6 only a handful more of these structures was actually

erected.

One major factor in Dawson's more respectable appearance was the

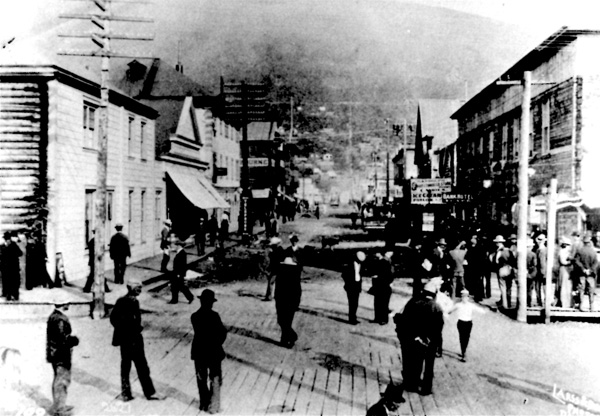

widening and macadamizing7 of the streets which served the

business core; that is, from Front Street to Third, and later to Fifth

Avenue for five blocks from north to south. By the time Lord Minto, the

governor general, arrived for an official visit in August 1900, the city

boasted five miles of graded streets planked at intersections and 12

miles of wooden sidewalks8 (see Fig. 31). The

harrowing stories of passageways clogged with mud, pedestrians and

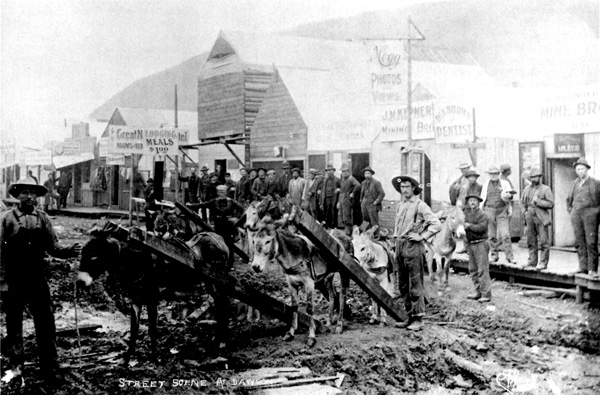

animals (alive and dead) were now only memories (Fig. 30). With

sophisticated nonchalance, the 1901 Dawson directory described the

buggies and carriages which passed freely along the thoroughfares. "A

pleasing sight of a summer eve is to see the many handsome turnouts

together with several hundred bicyclists lining the boulevard of the

waterfront in up-to-date Dawson.9

30 Dawson street scene, 1898. Each

heavy rain was a reminder of Dawon's swampy origins.

(Public Archives Canada, C 20891.)

|

31 A major intersection: King and

Front, ca. 1900. Contrast the road conditions to those in

Figure 30.

(Public Archives Canada,

C 13416.)

|

The extended use of electric lighting was clearly indicative of

Dawson's material progress. The Dawson Electric Light and Power Company,

incorporated in 1900, replaced several smaller concerns which had

attempted, somewhat erratically, to satisfy the city's need for

power.10 By the first months of the new century, some of the

town's leading trading companies had wired their stores to produce that

"clear white light so different from the smokey yellow glare of coal oil

lamps." In that same year the entire mining district was served by the

Yukon Telephone Syndicate. Two years later, 330 telephones were reported

to be in use in Dawson.12 Since some customers along the

creeks were as far as 50 miles from Dawson, the installation of a

working telephone system was an understandable asset to business.

One improvement essential to Dawson's physical survival was the

construction of a successful drainage and sewer system with provision

for a clean water supply. The excitement of the summer of 1898 had been

marred by a serious epidemic of typhoid, as well as by cases of malaria

and dysentery, all natural consequences of the unregulated

overpopulation of a poorly drained swampy area.13 While a new

board of health made initial improvements in 1899, it was not until 1900

that adequate sewer and water supply systems were

functioning.14

Probably greater than the apprehension of widespread disease was

Dawson's fear of fire. The two huge blazes which roared through the

overcrowded business district during the winter of 1898-99 had been

ample cause for a constantly alert fire department. By 1901 the

increased subscription support of the merchant community had equipped

the department with two engines, two hose carts, two chemical engines

and a hook and ladder truck; hydrant connections were gradually extended

along major arteries.15

In 1901, Dawson had unquestionably come of age. In no section was

this achievement more visible nor more enthusiastically praised than in

the business community. In fact this group was more responsible than any

other for many of the changes which effectively transformed Dawson into

an example of respectability. Few of the awed witnesses of

post-gold-rush Dawson failed to refer to the sense of "permanency" which

pervaded the city in general and its commercial sector in particular.

Nearly all made mention of the success of Dawson's prominent merchants,

the merchants whose large investments indicated their intentions to

remain in the Klondike market.

In a special "Midsummer Edition" in 1899, the Dawson Daily News

estimated the combined capital investments of the AC Company, the

NAT&T Company and the AE Company (the three leading trading and

transportation companies in Dawson) to be $5 million.16 An

assessment of 1901 showed that a total of 13 leading business houses

were valued at sums between $50,000 and $1.8 million.17

Architecturally, the city's exterior at the turn of the century

successfully projected the image of a thriving and prosperous community.

The commercial backbone of Dawson was composed of the row of stores,

hotels, small businesses and saloons which lined the entire length of

the east side of Front Street (later known also as First Avenue),

overlooking the chain of docks and warehouses which actually bordered

the shoreline. Here the impressive emporia of most of the larger firms,

as well as many of the city's finer hotels and theatres, were located on

the "line" or boardwalk (so called because of the 12-foot-wide sidewalk

which lined one side of that very wide street). Parallel to Front Street

and immediately to the east was Second Avenue, an equally busy

thoroughfare, where transactions occurred in every field from real

estate to confections, from prostitution to embalming. The nucleus of

primary activity extended as far as Third Avenue, the street singled out

in 1902 as the general artery of the town. Fourth and Fifth avenues

consisted mainly of warehouses and residences.

Quite a separate commercial and residential district grew up at the

southern tip of the city in an area which owed its sense of isolation to

the large tract of government reserve land which separated it from

Dawson's core. South Dawson, as the quarter-mile strip was known, housed

some of Dawson's more respected small businesses by 1901. Across the

Klondike River from this suburb lay Klondike City, maligned from an

early period by its universal nickname "Lousetown." The less than

sterling reputation of Dawson's younger sister was acquired in 1901,

when the Yukon Council ordered Dawson's birds of paradise to nest beyond

the city limits. The entire flock lighted in Lousetown. Councilmen were

hard-pressed to convince the more respectable — and now irate and

petitioning — residents of Klondike City that Dawson's demimonde

had not expressly been ordered to their shores.18

Two- and three-storey frame commercial buildings dominated Dawson's

streetscapes. While both the AC Company and the NAT&T Company

favoured the simple unadorned structures erected in 1897, the most

popular type of edifice still displayed some variation on the boom-town

front. Such fronts ranged from plain rectangular shapes to elaborate

outlines with peaks, parapets, domes and balustrades, often decorated

with highly ornamental friezes and cornices, contrasting woodwork and

trim (see Figs. 32 and 33). White seems to have been the predominant

colour of building fronts, but the general effect was by no means one of

blank space. The series of flat storefronts was broken by any number of

variations on the general format of large display windows on either side

of an indented doorway. Each store had its own colourful awning, often

striped, scalloped or bearing the owner's name. Presumably these awnings

were removed in the winter to let in the little sunlight that did

appear.

32 Boomtown architecture at its

rococo best, Front Street, 1904.

(Public Archives Canada, PA 14537.)

|

33 One of Dawson's main streets in 1904.

Second Avenue as seen from King Street.

(Public Archives Canada, C 14540.)

|

Photographs taken at the turn of the century provide contrasting

impressions of store-front signs. The majority show either letters

neatly painted on building fronts or unspectacular sign-boards affixed

over the central doorway. In one photograph, Front Street is festooned

with carnival-like banners proclaiming the remarkable bargains to be

made in various nearby shops. Perhaps Front Street tradesmen were among

the offenders singled out in a Dawson Daily News editorial early

in 1900 which complained of "those objectionable signs and banners,

especially those transparencies with lights" (Fig. 34). As Dawson prepared

for the upcoming visit of Lord and Lady Minto, the more "objectionable"

visible aspects of trade were ordered to be removed.19

34 Front Street in 1899: "those objectionable signs and banners."

(Public Archives Canada, C 6648.)

|

In the long run, this enforced and somewhat uncharacteristic tidiness

did not prevail in Dawson. A photograph of Second Avenue taken in 1904

(Fig. 33) reveals a muddle of signs, competing with wires and lamp

standards, on rooftops and overhanging the sidewalks — true

manifestations of urban North American enterprise. One element of the

tableau peculiar to Dawson in the long rain-free days of summer was the

transaction of business outdoors. Tradesmen extended their shelves,

crates, barrels, kegs and racks beyond the display windows and out onto

the plank sidewalks. During a closing-out sale (a regular summer

occurrence over the years) the heaps of goods and "selling out" sign

boards spilled over the sidewalk to the street itself, in open defiance

of the city's legal standards of respectable appearance.

Another unique feature of Dawson's skyline was the preponderance of

huge corrugated iron warehouses scattered throughout the city. By 1901

these structures numbered nearly 50, with a total capacity of some

50,000 tons.20 Even the earliest warehouses of the AC Company

measured in size from 30 feet by 50 feet to 30 feet by 190

feet.21 A good proportion of the entire capital investment in

Dawson lay within these warehouses, as well as its means of survival for

any entire year. The very presence of these enormous buildings was,

understandably, impressive (Figs. 28 and 35).

35 AE Company warehouses, ca. 1899.

(Public Archives Canada, PA 13297.)

|

When surrounded by such visible signs of prosperity, Dawson

residents, more than those of any other Canadian city, must have

continued to reflect upon the transience of fortune, the fickleness of

the paystreak. Even the most optimistic among them must have realized

just how tenuous was the validity of the city's nickname, "the Paris of

the North." Only the more cynical among them, however, would have dared

to interpret the town's newly gleaming exterior as a by-product of the

much sought-after goal of Dawson merchants, the lasting market. Without

this one promise of security no investment concern would have stayed in

that isolated northern valley.

The fact that they did stay represents the second phase in a cycle of

resource development. In proposing this theory, H.A. Innis suggests that

the phenomenon describes the slow death of a primary resource leaving in

its wake secondary industries, once urgently needed, as the basis of a

new but somewhat less productive economy.22 Given the

undoubted value of the Kondike's primary resource, as well as its

inaccessability, the capital outlay in the opening of the industry was

both extensive, immediate and necessary. The unusually high wages

offered to miners in the first year of the rush,23 the

immediate influx of established transportation and trading corporations,

the exorbitant cost of land and commodities and the immediate

construction of a rail connection all signaled heavy initial capital

investment.

In the service industries such investments could be repaid only if

increasingly efficient methods, firm markets and high prices

prevailed.24 Using Innis's hypothesis, one can appreciate the

influence of the Dawson merchant group as agents of change. Their eager

support of urban improvements was evidence of a sustained effort to

maintain business at a reduced overhead.

While operations were certainly made more efficient on many counts,

there were several basic aspects of doing business which remained

costly, to the chagrin of businessmen and, of course, of the consumers

who ultimately suffered unrelieved high prices. Rail and water

transportation companies provided increasingly good service to Dawson,

but the WPYR rates were still sufficiently high in 1901 to provoke what

was essentially a boycott of the line by both merchants and passengers

in the city.25

The lesson taught by one million dollars' worth of damage by fires

had prompted businessmen to subscribe to a good fire department.

Nevertheless, insurance rates remained high enough to be prohibitive

— 5 to 10 per cent in 1902.26 Commercial buildings in

the city core continued to be practically uninsured; risks were taken

only on stock in corrugated iron warehouses. The general opinion was

that these rates, too, were unnecessarily high.27

High insurance rates, coupled with rents which managed to reflect the

prosperity of the past rather than the present, ensured continuing high

storage rates. More than transportation, this matter of rents uniformly

affected all merchants, large and small.28 The territory's

Crown Timber and Land Agent, the official landlord of Dawson's

waterfront properties, was singularly guilty in failing to reduce the

rents of docking and storage facilities to a level in keeping with

Dawson's post-boom economy. A petition to the agent in 1904 from the

broker who had taken over the Seattle-Yukon Dock waterfront lease begged

him to consider that the contract had been made during boom times "and

certainly from a mistaken view of the permanency of the business then

prevailing." With the change in conditions, the rental value of the

property had fallen to one-third of its original value.29

For many of those who remained in the Yukon after the gold-rush,

permanency was forever an illusion; northern commerce, however

rationalized by technical progress, could never yield sustained profits

or security. For them, economic survival was possible under one

prevalent condition: consolidation. This constitutes the theme of the

history of the mining industry during the period; claims and capital

were amassed in order to apply modern technology rather than expensive

labour to the full exploitation of secondary gravels.

Commercial operations followed a parallel development. In 1901,

Dawson's business was estimated to be securely in the hands of the

following eight firms:

1) McLennan and McFeely, wholesale and retail hardware (reported to

have done the largest business of any firm in 1900);

2) The AE Company, general merchandise department store;

3) The Trading and Exploring Company, general merchandise;

4) Seattle-Yukon Trading Company, general merchandise;

5) AC Company, general merchandise;

6) NAT&T Company, general merchandise;

7) Ladue Company, general merchandise, and

8) Ames Mercantile Company, general merchandise.30

After this list had gone to press, the AC Company effected a merger

within this group, leaving no doubt as to the only solution to the

problem of duplicated overhead and services. On 1 June 1901 citizens

were shocked to learn that the AE Company, Dawson's great emporium and

owner of "the most magnificent and best appointed retail store and

offices north of San Francisco" had been taken over by the AC

Company.31 Along with it went the Empire Trading Company.

Four days later the president of the Seattle-Yukon Trading Company

arrived in town to hand over his firm — lock, stock, steamer and

warehouse — to the new company. The result, effective all the way

along the Yukon River, was the formation of two new corporations, the

Northern Commercial Company (the NC Company), which was to deal with

mercantile concerns, and the Northern Navigation Company to handle

shipping. W.D. Wood, the president of the Seattle-Yukon Trading Company,

explained his part in the amalgamation in rather magnanimous terms: "We

disposed of our holdings because we did not desire to oppose a movement

the prime object of which is to decrease the cost of living in this

northern country."32

Lois Kitchener, the historian of the NC Company, states that in 1901

no transportation company in the north broke even, and that the years

1901-03, despite appearances to the contrary, were not good ones for the

newly merged firm.33 Records are no longer available to

provide evidence for this statement. Nor do Dawson newspapers offer

confirmation, unwilling as they were to prick illusions of stability by

admitting the existence of bad times among the city's largest

investors.

While Commissioner Ross's report to the Department of the Interior

for 1902 contains the usual booster bravado on the subject of commerce,

Congdon's report in 1903 reflects seriously on the real state of

business for the majority of merchants.

Business generally in Dawson has been passing through a somewhat

critical stage. Formerly, when enormous profits were usual, men in

business made small fortunes in a year. Many of these . . . not

unnaturally concluded that increased investments meant corresponding

increase of profits, and put into business all available assets,

including those arising from excessively liberal credits . . . Business

is certainly on a more substantial basis now, although this result has

only been obtained after the unfortunate results to many former large

operators.34

An obvious feature of this state of affairs was the inevitable

decrease in Dawson's population. The depletion of high-grade gravels had

gradually turned placer mining from a labour-intensive operation into a

highly mechanized industry. While the legendary prospector of the Yukon

valley had been an independent operator, the majority of his

counterparts in 1898 were wage earners. If the widespread unemployment

of the winter of 1898-99 had not driven them back outside, the Nome

strike later that year offered them a second chance at the easy riches

and independence which had probably lured them to the Klondike in the

first place. An estimated 8,000 left for Nome over the winter of

1899-1900;35 after the mother lode had been discovered in the

Tanana district, 2,000 to 3,000 more evacuated Dawson for

Fairbanks.36 In consequence, the city's population, estimated

at 18,000 in 1898, dropped to 10,000 after the Nome discovery, to 9,142

in 1901 and to approximately 7,000 by 1903.37 With the

exception of the 1901 figure (which comes from a Dawson census) these

are approximations made by resident journalists. As such, they are

statistically unreliable but the general trend they record is

obvious.

While shrinking markets presented a setback to the whole community,

larger firms were clearly in a better position to weather the storm than

were the rank-and-file storekeepers. They had greater flexibility to

cope with changing demands and conditions for many of them were anchored

to established outside businesses.

It is therefore understandable that the NC Company of San Francisco

had sufficient capital to maintain its posts all along the Yukon River,

and could consequently profit from both the Nome and Tanana strikes. The

Ames Mercantile Company and the erstwhile AE Company, both of San

Francisco, were also able to command something of the Nome market by

opening branches there. The Pacific Cold Storage Company of Tacoma,

Washington, maintained branches in Nome, Dawson and along the river. The

NAT&T Company of Chicago and Seattle was also a long time proprietor

of a chain of Yukon River stores and trading posts. It opened branches

at Grand Forks (at the confluence of Bonanza and Eldorado creeks) and on

Sulphur and Dominion creeks in order to tap the market in the heart of

the Klondike district more fully.38 Such was the pattern of a

commercial system serving the placer gold-mining frontier. Like the

goldseekers themselves, company stores could be found at the site of the

most lucrative strikes. The operation of such branches helped offset the

inevitable rise-and-fall economic cycle of any single gold town. The

Vancouver hardware dealers McLennan and McFeely acted quickly in

establishing outlets not only in the Klondike but in Atlin and Bennett,

British Columbia, as well.39 As the initial rush through this

area died off, McLennan and McFeely closed its operations near the Yukon

headwaters to concentrate instead on the Dawson trade. All these

companies could, to some extent, offset the vagaries of the Dawson

market by operating branches throughout the territory.

In several articles of correspondence in 1903 and 1904, the Dawson

Hardware Company referred without regret to the slump in shelf hardware

sales. A conversion in mining equipment occurred as the industry

gradually turned to hydraulic operations. Like its competitor McLennan

and McFeely, Dawson Hardware was large enough to adapt itself to the

transition by producing and selling larger items of

machinery.40

Dawson, the reigning "gold rush town," unhappily surrendered her

title to Fairbanks in 1903. In one important aspect, however, the older

city did benefit from this rush, and its wholesale merchants were the

men to reap the profits. Dawson's short shipping season necessitated

year-round storage, which in turn produced the aggravating problem of

slow-moving or dead-end stock which was impossible to unload on a

decreasing population. A sudden strike in the north, with its

concomitant and immediate demand for all sorts of provisions, put Dawson

jobbers briefly in the fortunate position which their Seattle and

Vancouver antecedents had occupied half a decade earlier. While this

later rush was neither as large nor as sustained as the Kondike one had

been, the immediate impact on overstocked merchants was a healthy one.

Dealers whose surplus goods were American were especially fortunate, for

their stocks could enter Alaskan territory duty-free.41 In

1905 there were 24 bonded warehouses in the city with goods destined for

Fairbanks. The customs collector at Dawson claimed that year that the

previous season's trade with Fairbanks had earned Dawson wholesalers no

less than $750,000.42

The city's wholesale-retail firms made the most of Dawson's natural

position as the entrepôt for the Klondike hinterland. While

dealing in some retail trade themselves, an increasingly large part of

their business was ordering and shipping complete lines of goods from

outside for resale to retail outlets in Dawson and the creek

centres.43 At the same time, it was more convenient (if not

necessarily cheaper) for these merchants to buy their goods from local

wholesale dealers. They could at least count on suitable lines of

commodities, insured storage and more charitable terms of payment than

they might obtain from outside firms. Above all, the worrying trials of

long-distance ordering and shipping could be left to those larger

businesses better equipped to recover or absorb possible losses.

Whatever advantages the system might have offered the retailer, his

permanent subjugation to the jobber or wholesale supplier, local or

distant, was universally uncomfortable. In an article defending a

retailers' purchasing cooperative in Ontario, the Canadian

Grocer, always a friend of the individual merchant, sympathized with

the retailer's difficult position.44 The lot of the small

merchant in the shadow of the large wholesale firm was brought sharply

into focus by the Nugget during its war against the WPYR in July

1901. Not only did the WPYR charge more than the traffic could possibly

bear, the crusading Nugget claimed, but it gave preferential

rates to certain wholesale shippers. Although its charges were never

substantiated, the paper cited the firms McLennan and McFeely, Palmer

Brothers (general merchandise, wholesale and retail) and T.G. Wilson

(wholesale groceries) as examples.45

The percentage of Dawson's wholesale or jobbing trade which actually

went to the large multi-purpose companies, to the wholesale-retail

dealers in specific fields (hardware, dry goods, groceries, meats or

drugs) or to the amorphous group of wholesale importers and commission

merchants ("do you want to buy or sell anything?") can only be guessed

at. The only generalization one can hazard is that the initial

distribution of goods in Dawson became the prerogative of an

increasingly limited number of local jobbers.

The move toward consolidation within the Dawson merchant community is

not to be interpreted as a simple and drastic reduction of the number of

merchants participating in the trade. On the contrary, the number of

merchants in the city directories of 1901, 1902 and 1903 is overwhelming

and a numerical decline is not uniformly evident in this period.

(See Appendix G. Note, for instance, the number of grocers and

produce dealers, as well as hardware merchants.) One striking figure is

that of 135 merchants and traders without definite fields or locations

of business whose names appear in the alphabetical list of Dawson

residents for 1901.46 In what way these men and women did

their business we have little or no indication. The number of these

mysterious traders drops sharply to 41 in 1902; by the time the 1903

lists were prepared, they seem to have disappeared altogether. Those few

names which reappear do so in connection with well-defined trades in

groceries, hardware, second-hand goods or confectionery.

The incorporation of the city of Dawson in 1902 was undoubtedly the

prime cause of their disappearance, for with it came taxes and enforced

licensing of all businesses. Especially significant in this case was the

increase in fees for transient traders47 from $150 per annum

to $500.48 The annual spring scramble from the upper Yukon

River to supply Dawson with its first perishables was a lucrative

business, and these traders represented a get-rich-quick system which

seemed to show little regard for contributing to the growing community.

License fees were constantly evaded, but by June of 1902 the law had

caught up with the most blatant offenders, with the full support of the

outraged merchant community.49 By August, the heavy license

fee was uniformly imposed. Since these scow traders were not residents

of the city, there is no official record of their number, and no

indication of their reaction to the unavoidable fees. One suspects that

they, like the small permanent traders who suddenly fled Dawson, took

this as provocation to push on to richer frontiers.

Two possibilities exist to explain the next moves of these traders.

The more probable of the two is based on the idea that most individual

entrepreneurs did not last long on the frontier. They were likely to

return, richer or poorer, to the "civilized" heartland they had

originally left. This is especially probable in the cases of those

adventurers who had had no previous commercial experience. Mr. Bob

Bloom, once of Dawson and Fairbanks and now of Seattle, has suggested a

second possibility. Mr. Bloom was one of those Dawson traders who did

survive incorporation, but who sold out his hardware stock to join the

rush to Tanana, not as a merchant but as a miner. Bloom claimed that the

true northern trader was merely marking time, buying and selling to

support a much more fundamental quest. When the moment came, Bloom felt

little remorse in leaving Dawson, but he was to turn again to the life

of the general trader many years later in Fairbanks. Just as the

Alaska-Yukon directories do not reveal the cycle of Bloom's frontier

occupations, so we are left to imagine how the lives of those on its

pages labelled simply "trader" or "miner" must have passed through

similar patterns.

A third explanation of the fate of Dawson's floating merchant

population, and the most popularly accepted one, is that they moved

en masse to the creeks, in particular to Grand

Forks.50 This is hard to accept for a number of reasons.

First, Grand Forks was itself incorporated as the town of Bonanza in

1902; thereafter it imposed its own increases in licensing fees,

including a fee of $500 for transient traders.51 Second, the

directories for the years 1901-03 show very little increase in the

number of merchants doing business in Grand Forks (see Appendix H).

Third, none of the 135 small Dawson merchants and traders listed in

1901, or the 41 listed in 1902, appear in subsequent listings for

Bonanza in any capacity.

For various reasons, a steady amount of business was done on the

creeks. The activity at Bonanza in particular was enough to cause some

Dawson tradesmen to take notice, for the creeks seemed to be growing

progressively more independent of the centre.52 In the light

of this development, the commercial relationship between Dawson and the

surrounding creeks bears further examination.

Bonanza, located some 12 miles from Dawson, was able to offer most of

the services necessary to its own survival. As the largest of the creek

towns (its population was 4,133 in 1900),53 Bonanza was

described by one visitor as being actually busier than Dawson itself.

From the directories, it is obvious that no other creek offered the

variety of services found in Grand Forks. Men working on such distant

creeks as Sulphur, Dominion and Gold Run, well over 30 miles from either

Dawson or Bonanza, had to purchase their supplies at one of these small

creek centres.

Despite the presence of some local merchants on the more distant

tributaries, several diaries and personal accounts report long trips

(albeit only annual or semi-annual ones) into Dawson to buy the season's

supplies. One such account by a miner from Sulphur Creek, 35 miles from

Dawson, speaks resignedly of the muddy June trails which stretched the

journey into a two-day trip. Lower food prices and the opportunity of

exchanging the drudgery of mining for Dawson's urban excitement made the

long trip worthwhile.54 After a 25-mile trip into Dawson to

place his yearly order, one miner commented with unconcealed awe on

"some American Trading Company in which you could buy almost anything

you needed."55 While complaining bitterly about prices, the

miner marvelled at the rapid delivery of goods. "I'd hardly be there

myself before the store's dog-sleds would arrive with all that I

ordered. The whole supply would be delivered to the door without any

extra charge."

Until 1901, travel on the creek roads was arduous; consequently the

cost of freighting goods was outrageously high. Summer rates varied from

25 cents to $1 per pound, depending on the distance of the destination

from Dawson. Winter rates dropped by one-half, since the frozen trails

were considerably easier to negotiate.56 The miner from

Sulphur Creek quoted above tells us that an article which cost 50 cents

in Dawson was worth $1.50 once it had been transported into

camp.57 According to H.A. Innis, it was possible to pay ten

times the Vancouver or Victoria price for an article just to transport

it to an outlying creek.58 As the transportation of heavy

equipment such as steam thawers, pumps and boilers became increasingly

necessary, the annoyance of bad roads intensified.

As early as 1899 the Yukon Council had realized the need for better

roads, but an adequate network was not completed for several

years.59 By 1901 there were daily stage connections to the

creeks, and the 25 cents per pound summer rate to Grand Forks had fallen

to a more reasonable 3 cents per pound.60 Dawson's business

with the creeks that year was active enough to support eight freighting

companies on the circuit. In 1903 one visiting writer spoke grandly of

the fine government highway to Hunker Creek and of the many six-horse

stages that ran frequent trips into the territory. "Hence," he

concluded, "Dawson takes on metropolitan airs, and considers herself the

new metropolis of the far north and Yukon valley."61

Not all the general merchants on the creeks resigned themselves to

Dawson's superiority. As roads improved and rates fell, so their ability

to compete increased. Dick Craine of the Last Chance Hotel, General

Store and Museum on Last Chance Creek put an advertisement in the

Dawson Daily News late in the winter of 1900, announcing that "I

will compete in prices with any house in Dawson. Come and get my prices.

Pack train and delivery in connection. Give me a chance on your

freight."62 About a year later, the Nugget referred

with a certain sympathy to the small Dawson merchants whose businesses

were stagnating because of increased competition from the

creeks.63 According to the Nugget, the success of

these outlying traders was largely due to the exorbitant storage rates

charged in Dawson at the time, rates which creek traders were able to

avoid if they met their consignments right at the docks. No evidence

remains, however, to indicate the ultimate success of these creek

merchants in avoiding the Dawson wholesale middlemen.

The sphere of Dawson's commercial influence extended well beyond the

Kondike River and its tributaries. By 1902 the 307-mile

Dawson-Whitehorse road had been completed.64 To the Dawson

supplier, this meant not only that winter goods would have a better

chance of arriving intact but also that the completed road would give

rise to an uninterrupted chain of road-houses to be stocked. Needless to

say, Whitehorse jobbing grocers had much the same thoughts of possible

gains. Fort Selkirk, at the junction of the Pelly and Yukon rivers, some

175 miles from Dawson, seems to have emerged as the dividing point

between the Dawson- and Whitehorse-dependent posts.

While the division of spoils of the Yukon River trade was fairly

clear-cut, spheres of influence along the tributaries were more hazily

drawn. The Stewart River posts are a good example of this. An entire

general store outfit (for the Stewart River Trading Company) and

numerous individual consignments were sent out by steamer from Dawson in

1902.65 At the same time, the North West Mounted Police

detachment on that river was supplied through Whitehorse. The year 1902,

incidentally, marked the first occasion on which the Mounted Police

stocked their posts with goods "from home corners," as the quartermaster

put it in his announcement to the Dawson Daily News.66

This must have come as good news to both Dawson and Whitehorse companies

which might acquire contracts.

As the railhead, Whitehorse enjoyed a certain degree of commercial

activity on its own. It was never as wealthy as Dawson, for there were

no mining operations in the immediate vicinity. Yet a strike at nearby

Kluane Lake in the fall of 1903 provoked a great deal of excitement

among Whitehorse residents. The new strike was located on a headwater

lake of the Yukon River, just over 100 miles west of Whitehorse by

overland trail. Since Whitehorse, as the railhead, received freight on a

continual basis all winter long, it was in a good position to capture

the Kluane market. At this point the general merchandise trade in that

community was well under control in the hands of four major dealers. In

conjunction with a handful of specialists in hardware, men's clothing

and groceries, this group monopolized the services in the new camp.

Whitehorse itself was virtually deserted that fall.67 Its

citizens had spent too long a time as mere spectators to others'

stampedes: they were determined to have an active hand in this one.

The propitious effect of the Tanana strike on Dawson suppliers has

already been mentioned. Through a highly controversial point of Canadian

customs policy, these same suppliers enjoyed a continually strong market

in those downriver camps which, though in American territory, were

closer to Dawson than to Saint Michael. Merchants in these communities

(such towns as Eagle, Chicken, Steel Creek and Ramparts) soon became

frustrated when they tried to ship in American goods. The shortest route

was undoubtedly the upper river one; that is, the railroad through

Canadian territory. Canadian bonding procedure required that duty on

American goods be paid, to be refunded when such goods re-entered

American territory. But after coping with miles of red tape in the

customs office at Victoria, the receiving merchants found the refund

almost impossible to extract. American goods were still a large part of

Dawson's stock at this time (see "Satisfying the Sourdough

Appetite,") and victimized merchants soon discovered that it was much

simpler to buy from Dawson wholesale dealers. An added advantage was

that these goods could enter Alaskan territory under an Amerian

regulation as "American goods returned duty-free."68

Ironically, customs irregularities had helped to flood Dawson with

American goods in the first place. Now it was Dawson's turn to benefit

from similar confusion on the other side of the border.

If H.A. Innis's hypothesis that the initial Klondike boom period was

followed by a time of economic adjustment is accepted, then one can

legitimately view commercial activity in the period 1899-1903 in terms

of reduction and consolidation. This trend was most profitable for the

larger wholesale and retail establishments which could better adjust to

the change. The diversity of their activities would ultimately be the

factor which left to them the fulfillment of Dawson's role as Klondike

metropolis. Conversely, such commercial progress was apt to be

disastrous for the plethora of now-redundant traders and small merchants

who had once jammed Dawson's streets, for their stake in metropolitan

prosperity was a peripheral one indeed.

Such an insistent stress upon commercial consolidation might create

an unnecessarily bleak picture unless a related view of Dawson in this

period is also considered, for during these same years Dawson blossomed.

A number of experienced and specialized storekeepers had built up known

and respected businesses by maintaining high quality in their

commodities and by stocking lines as varied as could be found along any

main street outside. Variety and quality were more than anyone had dared

hope for in the rough and ready days of "tent city" hawkers. They were

qualities which Dawson merchants learned to provide.

|