|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 26

Grubstake to Grocery Store: Supplying the Klondike, 1897-1907

by Margaret Archibald

Satisfying the Sourdough Appetite

To the family:

Laura may tell Frank Gross that we disposed of

that pail of ham the same as we do of all grub, eat it up very quick.

The dried fruit that his mother gave me went the same way, and all that

Mother sent except the cherries. We have a lot of dried apples, peaches,

apricots and such stuff we bought in Seattle. I do not miss the grub we

have at home as much as you would think, but I will probably have a good

appetite for it by the time I get home next June.1

And so he probably would, for this miner, writing

from Sulphur Creek in June of 1898, still had a long way to go on the

crest of his optimism. His cache of dried fruits and vegetables, bacon

and flour was still good; he would probably depend on these staples for

his winter survival. While there were, of course, more interesting foods

on the market in Dawson, the creek worker could afford neither the time

nor the money to procure them.

Winter thawing was a long, tedious, back-breaking

task — one which is too rarely brought to mind by the romantic

concept of digging for gold. Only one man was released from this work at a

time to take charge of cooking, a chore which in some cases involved no

more than cooking up quantities of sourdough bread and beans. Cooked

beans could be left to freeze solid; the cook could then hack off a

chunk of them with an axe and heat them in skillet grease when

necessary.2 These solid victuals were consumed along with

bacon and coffee, tinned or dried fruits and vegetables when they were

available. For that first winter, at least, it was sourdough bread and

brown beans — not the excitement of scooping nuggets from creekbeds

— which kept the Klondiker's body and soul together. The first of

these staples, sourdough, was such a thoroughly rooted Yukon tradition

that it lent its name as a sobriquet to the Yukon old-timer.

"Sourdough" described the pungent taste and smell of the fermented

paste, or starter, which was used to start the leavening of dough. Why

the name was earned by anyone who had spent one winter inside has never

been successfully explained.

There were innumberable possible variations for the

baking of sourdough bread. Two follow. The first recipe was used by

Martha Louise Black in her earliest days in the Yukon. This recipe

employs the traditional starter, a rising agent made ahead of time

without the benefit of store-bought yeast. A small amount of starter was

saved each time for subsequent bread-making:

Mix a thin batter of flour and water. Add a little

rice or macaroni water and a pinch of sugar. Put mixture in a pail,

cover it and hang over the stove, keeping it warm for four hours.

Sourdough may be used to raise bread, pancakes and doughnuts. For

pancakes use a pinch of soda.3

The second recipe was included in his diary by a

Sulphur Creek miner.

6 cups flour

5 tea spoons baking powder

2 tea spoons salt

mix well

4 cups water4

The final traditional Klondike touch came with the

baking, for the bread pan was the prospector's gold pan. With more

modern methods of working dumps, the miner's pan was relegated to what,

up to that point, had been its secondary functions as a vessel for

baking bread and washing up.

The only food which could rival bread as a dietary staple was brown

beans,

which exactly ressemble [sic] the ordinary beans supplied to

horses, and require boiling for about 3 hours before they become

sufficiently soft. They possess strong nutritive and heating properties

and in those days, when meat could only be obtained at fabulous prices,

were consumed in enormous quantities. They were not unpleasant to eat

when there was nothing else, and went by the name "Yukon

Strawberry."5

Such a dispassionate observation must have

come from a man who wintered on something of a deluxe outfit.

Even a full stomach of bread and beans was not enough. The constant

exposure to cold, the unrelieved monotony of mining, the dark, airless,

unhygienic cabins and the endlessly repeated menu all contributed, if

not to scurvy, to a most depressing physical condition. As late as 1900

a boy wrote from the creeks,

Happily the cold air and the work do sharpen our appetites and we

could relish sawdust and garlic.

The succulent (and flatulent) bean is the mainstay of the miner

during the winter. In Dawson, one can feast on oysters, frogs' legs,

fresh eggs and beef, but on the creeks, while we may sigh for such

delicacies we are content to feed on the meat of moose or caribou,

bacon, canned mutton or canned roast beef.6

Moose, caribou and smaller game as well as fish in season were some

of the few concessions made by the Yukon to provide for these newcomers.

Even then, such concessions were not direct ones. If cheechakos were not

suited to the arduous miner's life, they were even less competent as

self-sufficient men of the bush. The inclusion of bacon and tinned meats

in an outfit was presumably intended to free the goldseeker from the

necessity of hunting. When the tinned meat ran out and the bacon became

unbearable, the cheechako could obtain game from the natives who had,

until recently, depended on it themselves. With their moose pastures

overrun by foreigners and alien gold-extracting equipment, many of these

bands had turned to exchanging their game for the gold they had

previously ignored. One band camped at Moosehide each summer to be

nearer the lucrative market at the Klondike's mouth.7 Winters

were particularly productive, for during that season native life was

"enlivened by quick trips to Dawson and the mining camps to sell meat at

inflationary prices."8

Throughout the year, weekly newspaper reports of fish and game prices

were regular features of the Dawson commodities market.9 One

sourdough recalled that caribou meat was tender and palatable, but less

energy-giving than moose, beef or pork.

It doesn't stay with one as long. Moose has all the consistency of

beef and is the same. The bulk of the meat is ... stringy but the steaks

are equal [to] beef steaks. It may be kept [frozen] in summer for

as long as required by placing in glacial streams.10

Some of the more fastidious urbanites who had rushed to the

goldfields ignorant and unquestioning were somewhat squeamish about

eating fresh game.11 Too late they realized that fresh meat

of any sort was all too rare an occurrence in the early Dawson

market.

One assistant surgeon for the North-West Mounted Police was very much

aware of the positive relationship between varied diet and high morale

among his men. As late as 1900, isolation and the lack of diversion were

considered by Dr. Paré to be a serious danger to the mental health of

the force. To counteract these conditions, he ordered that rations be

made as appetizing as possible, even though most food still came from

tins. "It is a daily and amusing sight," he remarked, "to see them going

to their mess with cans of peas, corn, fruit, cream, milk, bottles of

pickles, sardines, etc."12

The territorial health officer in 1899, Dr. J.W.

Good, was similarly concerned about the well-being of Dawson's

predominantly male population (80 per cent of the population in

1899).13 If more women came north, he reasoned, their talents could be

turned to raising vegetables, chickens and cows. The positive

influence of family life in Dawson would put an end to scurvy once and

for all.14

One northern woman who agreed with Dr. Good's

philosophy was Mrs. Clarence Berry, the wife of one of Dawson's original

Bonanza kings. She had accompanied her husband over the pass in 1895

because she thought that women had an essential role to

play in the goldfields, cooking for their men to

prevent sickness and stomach-aches. She strained her imagination to

produce a wholesome diet out of tins, yet despite her efforts, she still

pined for anything fresh, raw or green.15

Martha Louise Black found her culinary talents

similarly challenged by the limitations of an outfit and a general food

shortage in trying to cook decent meals for lonely and hungry miners.

This is Thanksgiving month, and I am going to celebrate with a

dinner. It is difficult to cook here, with granulated potatoes,

crystallized eggs, evaporated fruits and vegetables, canned meat and

condensed milk, but I have made mincemeat and it is prime. 16

She came up with the following menu:

Canned tomato soup — Bread Sticks

Oyster patties — Olives

Baked Stuffed Ptarmigan

Canned Corn — Dessicated Potato Puff

Bread — Butter — Pickles

Mince Pie — Cheese — Coffee

Popcorn Balls — and a taste of your Home

Fruit Cake (the larger part to be saved for Christmas).

In the isolated winter life of a miner,

Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year were bright moments indeed, moments

when the cabin walls seemed less confining, the surrounding wilderness

less oppressive. Such occasions called for cabin-to-cabin socializing

— something of a luxury in itself, when there was thawing and

digging to be done. Friends from the same hometown might get together

in one cabin to sing and dance and eat as fine a meal as could be

assembled from the best of the combined outfits.17

Roast moose often took the place of turkey,

accompanied by the traditional cranberry sauce, if someone had managed

to hoard a little.18 Mince pie or plum pudding was another

special treat, pulled from a corner of the cabin where it had been

stored for the occasion. For one group of miners, the celebrational

dinner consisted (by necessity) of dried potatoes, bacon, rice, evaporated

fruit and their last can of tomatoes as a treat.19

In recording this dinner in a letter to his sister in

England, a young miner reflected unhappily that whatever Dawson had for

sale lay far beyond the reach of an ordinary miner working a claim deep

in the Klondike valley. By the fall of 1898 the city boasted both

specialized and general retail establishments which were known for their

choice merchandise. In fact, one resident of Dawson and the creeks

from 1898 to 1901 declared that "there was little you couldn't get there

provided you had the money."20

Most Dawson residents, however, were as limited by

economic considerations in their choice as were the workers on the

creek-beds. They too grew tired of tinned goods, the inescapable

social leveller. Long after the outfits purchased in Vancouver had run out

and Dawson warehouses had been fully stocked in all lines of new goods,

tin cans continued to dominate Dawson's shelves — as well as its

hillsides.

As we approach the confines of the town the chief

object that attracts the eye is the immense number of empty tin cans of

every size and description, which lie in thousands upon all sides of the

innumerable log cabins dotted about on the rocky hill slopes. The poorer

inhabitants appear to live exclusively on canned food and there is

surely here a great field open for an enterprising inventor who can put

the masses of empty tins, which are thrown away in such quantities, to

any practical use. The motto "One people one tongue" much quoted in

Dawson, evidently refers to the canned commodity which forms the staple

food of the Anglo-Saxons of the city. 21

Fruits, vegetables, milk and cream, butter,

crystallized eggs, meats, fish (especially salmon), soups, baking

powder, yeast, baking soda, cocoa and coffee had all been sealed, at one

time or another, in those metal containers which lay strewn outside

Dawson cabins. Baking powder tins, because of their size (a 2-1/2 lb.

"Imperial" tin was 8 inches high and 4-1/2 inches in

diameter)22 were used as storage tins in the kitchen. Laura

Berton recalls that miners often stored their gold dust in these large

cans.23

Yukon sourdoughs seem to have developed one common

characteristic as a result of their first qualifying winter inside. Each

one acquired a lifelong and unshakable loathing for one particular dish

on the Dawson menu. For many it must have been one of the types of

evaporated vegetables. The humble turnip may indeed have had the power

to prevent scurvy, but it seems unlikely that it won many admirers in

the Klondike in its evaporated form.

The granulated or dried potato was another item

which, like the brown bean, won less than enthusiastic acceptance on

Yukon dinner tables. "Lubeck's" German sliced potatoes led the

field. The white substance, which rather resembled rice, was soaked in

cold water and then doused with boiling water; so softened, it could be

fried in bacon fat or butter.24 Perhaps the widespread use of

the granulated potato in Dawson is best illustrated by the fact that the

whole fresh potato was set apart by a special name, "cheechako potato,"

as being new to the territory. It was an expensive novelty at that. In

1899 one man who struck a rich claim celebrated his sudden wealth by

splurging on fresh potatoes. He

bought 100 pounds which, at the prevailing price,

would have cost him $25. Ella Hall, who recorded the event, felt

especially elated because, as a friend, she had received some of the

treasured tubers.25 By 1902 whole potatoes (as well as

onions) were available year-round and "Lubeck's" registered a distinct

decline in sales.26 The price of fresh potatoes had dropped

from the 25 cents per pound which the rich miner had paid three years

before to a steady 9 cents per pound in 1902.27

The advent of cold storage in Dawson had had a

decisive effect in enlarging the range of the city's diet. Cheese,

butter, eggs, apples, citrus fruits, bananas, fish, poultry, meats, root

vegetables and grains could all be kept in this say anywhere from 6 to

12 months.28 Dawson, like the rest of Canada, was

experimenting in a new process in dealing with

perishables.29 Across the country cold storage was greeted

with general public discredit; most consumers insisted on "strictly

fresh" goods.30 But the northern customer was, unlike his

far-off countrymen, in no position to make such demands. Cold storage

had reintroduced whole meat into his diet and had rescued him from a

life time of "Lamont's" crystallized eggs, "Lubeck's" evaporated

potatoes and J.B. Agen's canned preserved butter.

On the other hand, creek workers who continued to do

their shopping in Dawson on a twice-yearly basis kept the canned meat

and vegetable trade flourishing.31 A good week of frozen

trails in the fall meant heavy purchasing traffic from the creeks, and a

noticeable strain on the supplies of "Reindeer" milk or canned peas and

beans.

Still, many comparatively privileged Dawson residents

found that, after a few years, even cold storage food acquired a sameness

in flavour which made one crave the "strictly fresh." Martha Louise

Black yearned for dietary escape from the ten-month-old-egg. Mrs. Black

(who was by this time the wife of Commissioner George Black), was

adventurous enough to decide that she would have to raise her own

chickens if she was to have fresh eggs on a regular basis. Accordingly

she sent to Vancouver for six dozen hens. Each and every fresh egg she

relished, until she found out that the chickens had not prospered in the

northern climate; all along her husband had been buying crates of the

same cold-storage eggs which she believed that the gardener was

delivering "fresh from the hen-house."32

The type of food which cold storage really freed from

the confines of tin cans was meat. Without the benefit of

refrigeration, Dawson had no access to the products of southern

slaughter houses. The only alternative was to ship in livestock,

butcher it in Dawson and freeze the meat on the spot. This was no simple

matter, given the obstacle course between Dawson and the

coast which had defeated beasts far more agile than

beef cattle. Jack Dalton spent his gold-rush days laying a trail to

skirt the passes on a wide sweep from the Lynn Canal to Fort Selkirk.

For over 300 miles the footpath was long and rugged, but it avoided the

treacheries both of the mountain pass trails and the upper river rapids.

During the summer of 1898, some 2,000 beef cattle were herded over this

route to the river.33 When the overland trail from Whitehorse

to Dawson was completed in 1902, herding was made even easier. During

the winter, the stock was slaughtered at Whitehorse to save on additional

feeding, and the frozen beef, pork and mutton were shipped over the ice

from there.34

The greatest material improvement in Dawson meat

provision was made by the Arctic Meat Company in 1899. A 250-horsepower

steamer, the Lotta Talbot, was fitted out with liquid ammonia

refrigeration compartments. She was constructed to make both the Pacific

voyage from Seattle to Saint Michael and the shallow river journey up to

Dawson. After a little more than two months of travel she arrived at the

Dawson wharves, offering wholesale or over-the-counter meats to the

city. The meat sold by this Puget Sound company was reputedly killed in

its prime rather than after being driven to exhaustion over icy

trails.35

By 1901 a similar firm, the Pacific Cold Storage

Company, had entered the country from Tacoma, Washington, with both

sea-going and river refrigeration steamers. It offered public storage and

wholesale meat supplies at all points along the Yukon River as far

upriver as Dawson. Meat was also brought in by the WPYR, which, by the

same year, had installed special cars for transporting perishables.

At Whitehorse, the Canadian, the Columbianor the

Yukoner lay in berth to carry the refrigerated cargo down to

Dawson.36 With this modernization of cargo carriers, Swift

and Armour, both large American meat distributers, could look to Dawson

as an extension of their commercial empires.

The prospect of local ranching had been discouraged

from the start by the scarcity of nearby grazing land and a short and

uncertain growing season. A red-topped hay grew wild in some Yukon

valleys and meadows, but such fertile patches tempted only the hardiest

ranchers.

Much more successful experimentation in both

agricultural and monetary terms was done with vegetables. Such

experimentation was not a recent phenomenon in those latitudes. One trader,

Arthur Harper, had persisted in growing vegetables at every yukon post

at which he served.37 Small sandy plots were ideal, and while

the growing season was, of course, short, the long hours of daylight

could be relied on to produce unusually large vegetables.38

Nonetheless, the factor which most encouraged

the success of Yukon market gardening was the

ready-made market of eager Dawsonites.

C.M. Bartholam and James A. Acklin were two

entrepreneurs of 1898 who foresaw the effect of fresh produce on a

population hitherto dependent on tinned goods. Cultivating land just

above Dawson on the Klondike River, Acklin tried out various types of

lettuce, cabbage, cauliflower, radishes, peas, spinach, mustard, "sweet

peas," carrots, turnips, pea and string beans, onions, beets, rhubarb

and rutabagas.39 Like Acklin, Bartholam discovered that

there was more than one way to extract gold from the Yukon's banks. One

of the first water pails of greens from his Klondike River plot sold for

more than $100 to a northerner starved for fresh

vegetables.40

By the next harvest season there were 12 local

gardeners concentrated in the valley around Dawson, the Klondike River,

the flats at the river's mouth (near the Ogilvie Bridge) and the area

across the Yukon known as West Dawson.41 From that time on,

the city's summer residents were treated to fresh vegetables of all

kinds. In addition to those successfully cultivated by Acklin, local

strawberries were particularly good as a cash crop: a small box always

sold for more than a dollar.42 Potatoes, although prolific,

were never considered mealy enough to contend seriously with the cold

storage variety. Early frost and old seeds from the outside were

additional problems which hampered the immediate success of market

gardening.43 Nevertheless, Dawson consumed everything that

was grown in both market and private gardens. Even in competition with

fresh goods rushed in over the ice, early local lettuces and radishes

sold out as soon as they appeared on the market each

June.44

But fresh vegetables retailed at an average price of

12 cents per pound, and not everyone could afford them. Restaurants

found themselves tied in the same way to tinned goods because of the

prohibitive prices of local fresh merchandise.45 In four

years, however, the status of homegrown products had changed;

Commissioner Lithgow claimed in 1906 that importation of turnips,

carrots, beets and celery had almost ceased.46 The evaporated

vegetables seem mercifully to have passed by 1907, but tinned fruits and

vegetables were still regarded as staples. Dried fruit remained a

popular item as well.

In the realm of grains and cereals, Dawson's tastes

changed little during and after the gold-rush. Flour and rolled oats

were still staples. While there was an increasing number of bakeries in

town (the 1902 directory lists 13), breadmaking held its place as a

normal kitchen activity, especially in the growing number of homes where

wives had come north to supervise miners' eating habits.

There was one major change in cereal products which

registered as something of a fad across the continent during this period.

The idea of prepared breakfast foods, which began with the boxing of

"Quaker Oats" as early as the 1870s, had taken hold.47 By

1903 a substantial corner of the Dawson grocery store was needed for

boxed cereals, if the storekeeper intended to keep up with the almost 20

brands which were available to the market (see Appendix B). Steamed

cereal was considered an especially sensible way to start a Yukon winter

morning.

A major advance in the Dawson grocery trade after the

gold-rush, and one of which merchants were visibly proud, was the

increased range of specialty items or luxury goods which brightened the

rows of shelves. Many of those who reported spartan Christmas meals in

1898 would not have to repeat the menu the next year. Once his first

outfit had been consumed, the customer could take advantage of the many

delicacies which were advertised at the Christmas season. Besides the

turkeys and plum puddings which were expected at most tables, the Dawson

merchant made the most of his fancy stocks of wines and wafers, special

apples and raisins, nuts and biscuits, candied fruit and other such

treats in boxes, tins and bottles. "Crosse and Blackwell" figured

prominently in these seasonal advertisements for luxuries which would

have seemed too expensive at any other time of year.48

Foreign names abounded as candy and prunes from France, oranges, grapes

and raisins from Spain or Turkey and nuts from South America made their

special appearances in the showcases.

Also in step with the times were the menus in those

Dawson restaurants which maintained any pretence to elegance. The menu

of the Holborn Cafe in the spring of 1900 offered such delicacies as

oyster cocktails and lobster salad on mayonnaise, queen olives, eastern

shad au gratin, fricandeau of veal à la macedoine and English

plum pudding with brandy sauce.49 All one can hope is that

the elaborate names were accurate descriptions of better and more

appetizing food than the beanery meals of 1898 had been.

For those who preferred and could afford to prepare their own

gourmandises, speciality items were available all year round. One

advertisement from the Ames Mercantile Company in 1900 offered the

consumer everything from shrimp in tomato sauce, devilled ham and vienna

sausage to French prunes, pitted plums, New Orleans molasses and fancy

table syrups. In fact it seems, from scanning grocery lists in

Canadian Grocer and Eaton's catalogue, that the average Canadian

at the turn of the century had a greater craving for fancy fruits,

jellies and condiments in pots, tins and bottles than do his descendants

today. Stanley Scearce, a Dawson commission merchant and importer,

appeared to dominate the field of fancy goods in 1907. His store stocked

items which ranged from "Cresca" stuffed dates to "Averbach" German

truffled liver. He also advertised peanut butter, which made its first

appearance in Dawson around 1907. For a large jar of the substance

Dawson consumers paid one dollar.50

To speak of "imports" to the Dawson market can be

somewhat confusing for the word has a variety of connotations. Foremost

in the mind of the average resident was the fact that nearly all goods

had to be imported from far beyond the Yukon's borders. As the awareness

of Dawson's vulnerability to American goods increased, "import" came to

refer to goods from American rather than Canadian producers. In the

field of fancy groceries, the word "import" maintained the idea that the

item came from distant ports.

By 1902 several influential articles had pointed out

to Canadian manufacturers the extent to which the Yukon diet was

dependent on American goods.51 Tinned goods, packaged dairy

products, ham, bacon, lard, flour and evaporated vegetables were areas

which were primarily supplied by American sources. Most dairy products

and flour came from Washington and Oregon and most fruits and

vegetables from California, although Australia and New Zealand provided

some of these goods. The competitive Canadian products in these fields

(especially dairy products) usually came from Ontario, as did many

overseas shipments of such things as teas, coffees and dried fruits, and

were distributed by centrally located jobbers there.52

The quality of the edibles on the cabin shelf had

vastly improved since the concentrated and dessicated days of 1898. But

beans and canned goods might continue to dominate many a table over the

next decade, for not every miner could afford paté de toie gras

from Stanley Scearce. Still, those merchants who advertised regularly in

the local newspapers in 1902 appeared to have had an extraordinarily

wide variety of stock, even in staple items.

These advertisements were interesting for their lack

of convincing rhetoric and descriptive journalism. Mere lists of goods

and prices sufficed in most cases. By 1902 some brand names were

mentioned, but no consistent and focused effort was made to sell one

brand of goods in any line. The popularity of one brand was often

inferred only through repetitious references by more than one store; by

this means one can presume the success of such brands as "Rex" meats,

"Heinz" and "Crosse & Blackwell" products, "Ogilvie's" flour, and

J.B. Agen's butter. Over the years only a handful of manufacturers and

distributors advertised their goods directly in Dawson newspapers.

"Lamont's Crystallized Eggs," "Hand--Y Brand"

evaporated fruits and vegetables, "Blue Ribbon" and "Salada" teas,

"Durkee's" spices, "Libby, McNeill and Libby," "Clark's" meats,

"Ogilvie's Blue Label" flour and J.B. Agen's butter were among the few

products which were advertised in this way (Figs. 37 and 38). After 1902

this practice occupied increased space in the pages of the Dawson

Daily News.

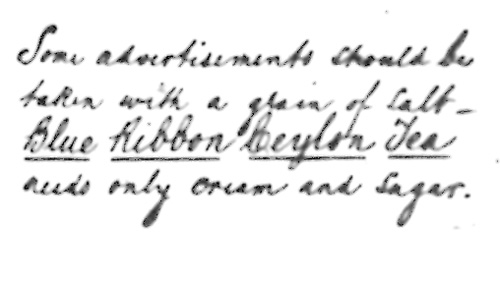

37 "Some advertisements should be taken with a grain of salt —

Blue Ribbon Ceylon Tea needs only cream and sugar." A common

advsertisement in the Dawson Daily News in 1902.

(Dawson Daily News, 10 June 1902, p. 3.)

|

38 "Hand--Y" brand evaporated fruit, advertised in the Klondike

Nugget in 1898.

(Klondike Nugget, 16 June 1898, p. 4.)

|

The more popular method of advertising was done

directly through the retailers of the product.53 In his own

store the merchant felt the greatest responsibility for the sales of

certain brands of goods. As technology in the last half of the 19th

century brought both the packaged product and the widespread marketing of a

recognized brand name, the manufacturer and distributor encouraged the

individual merchant to vouch for his product. The storekeeper, it was

reasoned, would appreciate the increased efficiency in handling (e.g.,

packaged cereals as opposed to bins of rolled oats) as well as a

reliable clientele if he stocked only one company's goods.

The transition made a tremendous difference to the

store's interior. Shelving became the primary method of display, since

the majority of products were in tins, bottles and packages and could be

displayed that way. In addition, colourful placards, posters, cut-outs,

bunting and plaster models were obtainable from the manufacturer for the

purpose of advertising the brand name of that company's

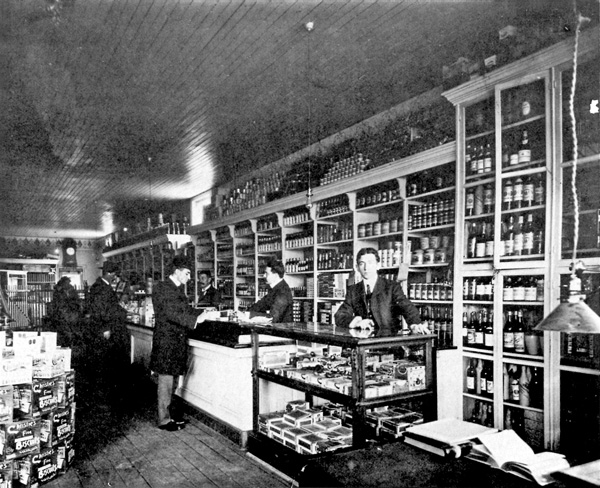

products.54 The NC Company store displayed this kind of

interior advertising (Fig. 39) as various company-sponsored

advertisements competed for the customer's eye. Merchants with

imaginative or artistic capabilities could build a rather elaborate

display around the product, placards and models.

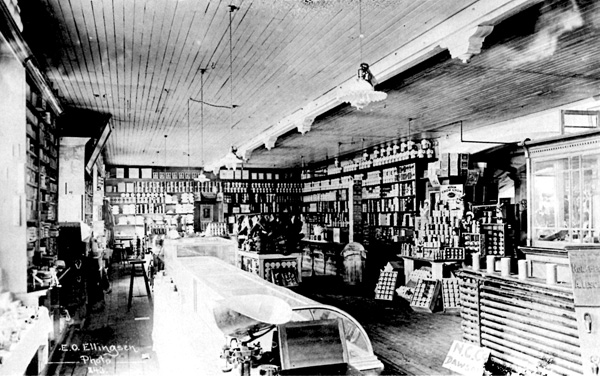

39 The grocery department of the Northern Commercial Company, 1909.

(Public Archives Canada, C 3014.)

|

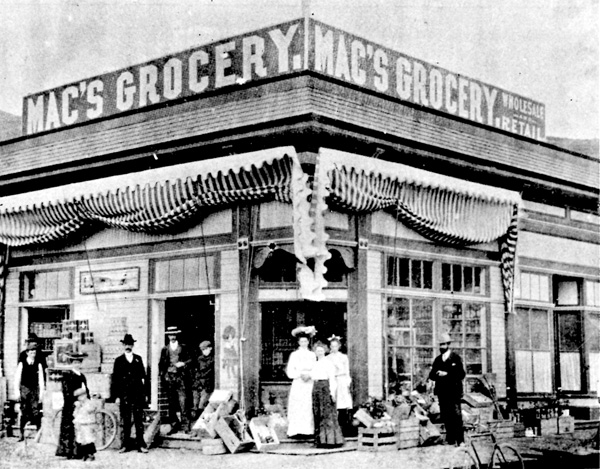

Ornate window dressings in grocery stores were

particularly popular among the subscribers to the Canadian

Grocer. Photographs, hints, criticism and praise directed at

particular window displays of this or that grocer became a regular

feature between 1903 and 1905. The accompanying articles stressed time

and again the importance of imaginative visual appeal in these displays.

It appeared that great pyramids of packaged products surrounded by large

placards bearing the company's name, along with sundry related

decorations, formed a most popular genre of window dressing (see

Fig. 40). While Dawson photographs offer glimpses of small piles of

goods in the window (Fig. 41) there seem to have been no grand

expositions on the British model suggestive of those in the Canadian

Grocer. This may, however, be the result of a gap in the pictorial

record of the city rather than a lack of sophistication on the part of

the merchants. The fact that many of the smaller stores opened out onto

the sidewalk for the light summer months may also have

limited window display (Fig. 42).

40 An exemplary grocery window display

(Canadian Grocer, Vol. 17, No. 50 [Dec. 1903], p. 50.)

|

41 The Dawson grocert did not always pay as much attention

to his window displays as did his southern counterparts.

(Public Archives Canada, PA 13279.)

|

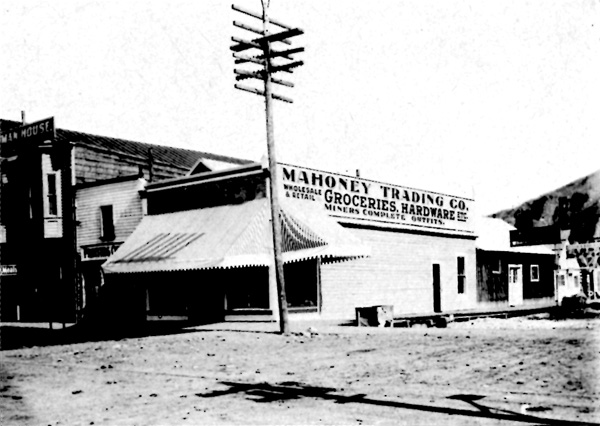

42 Mac's Grocery, 1903-05. Dawson stores extended to the

sidewalks in summer.

(Public Archives Canada, C 7068.)

|

The interior appearance of any well-appointed store

was thought to be an essential factor of good salesmanship. In this

matter the Canadian Grocer weekly espoused the cause of neat and

tidy displays. Now that packaging was coming into its own as a refined

commercial art, the pleasing array of goods in a store began to take

over from the chaotic floor-boards-to-rafters approach of the previous

century. "Within recent years it has become a generally recognized fact

that appearance is to a grocery store almost of the same importance

that clothes are to a woman. They are not everything but they account

for a great deal."55

As with window displays, the Grocer made a

regular feature of discussing the artistic and mercantile merits of the

interiors of various Canadian establishments (Fig. 44). The pyramid or

the three-dimensional stack of tinned and boxed products was

universally popular, relying on floor-to-ceiling wall space along one whole

wall of the store. Central display tables were used for some items,

often in conjunction with brand advertising cards. Goods to be displayed

in cartons, such as fruit, biscuits or candy, could be leaned against

these central islands, leaving the counters free for conducting

business. Showcases were also used for these sorts of goods, and in

some stores for the grain products which had previously been hidden away

in bins.

43 Grocery department, North American Transportation and

Trading Company store, Dawson, ca. 1901.

(The Library of the University of Alberta.)

|

44 A store selected by the Canadian Grocer exhibits a

popular display style.

(Canadian Grocer, Vol. 18 [July 1904], p. 53.)

|

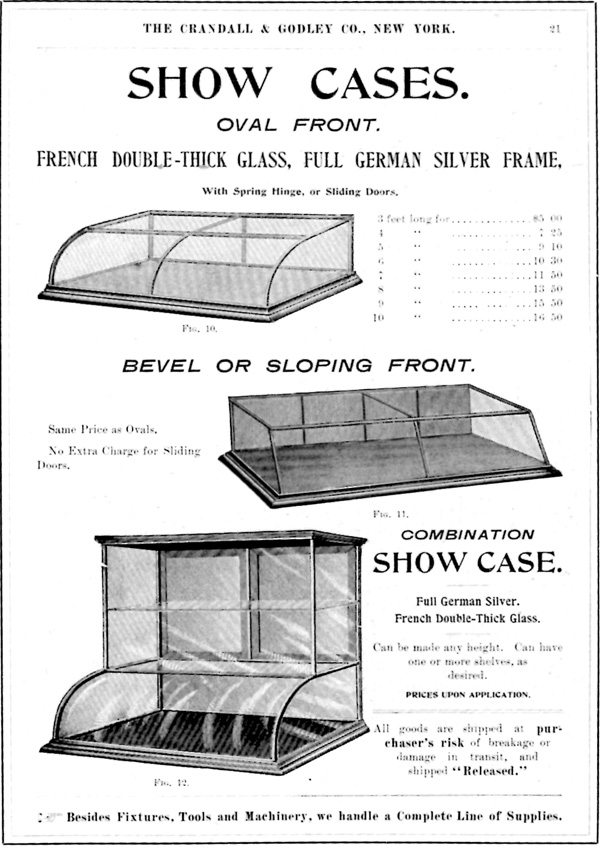

Flat, bevelled and sloping front glass cases were

popular along the counters. In some establishments the display cases

were built right into the shelves (Fig. 45). The Canadian Grocer

had the following advice on the judicious and aesthetic use of store

space:

Barrels in sight, whatever the position may be,

are not features of a neat interior. Counters should be free from almost

all stock save what must be kept in show cases, and the office must be

well built wherever it is placed. Neatness must exist in every successful

store, and to obtain this the stock should be confined as much as

possible to the shelves, show cases and fixtures specially made for the

purpose.56

45 Glass showcases intended for confectioner's displays, 1897.

(Crandall and Godley Company, Bakers', Confectioners', Ice

Cream Makers', and Caterers' Supplies, Tools, Fixtures, and

Machinery [New York: n. p., 1897], p. 21.)

|

Photographs of Dawson's commercial interiors show a

marked similarity to those selected by the Canadian Grocer for

favourable comment. Dawson merchants were obviously determined to keep

pace with the latest display techniques (Figs. 39 and 43). In the NC

Company's grocery department of 1909 only one barrel is in evidence; it

contained ginger snaps. The cracker barrel had disappeared, and along

with it a whole style of country store-keeping. Christie's appeared to

have dominated the packaged biscuit business, but the open carton of cookies at

the end of the counter never entirely disappeared.

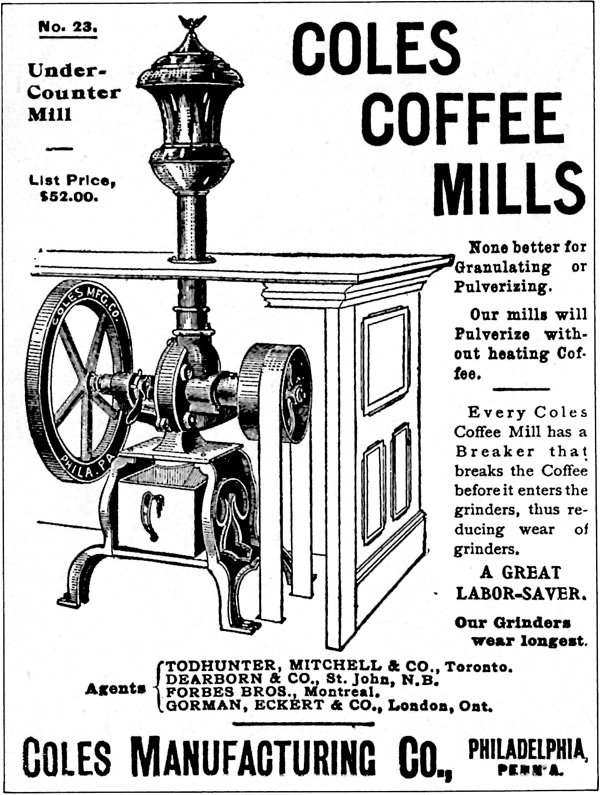

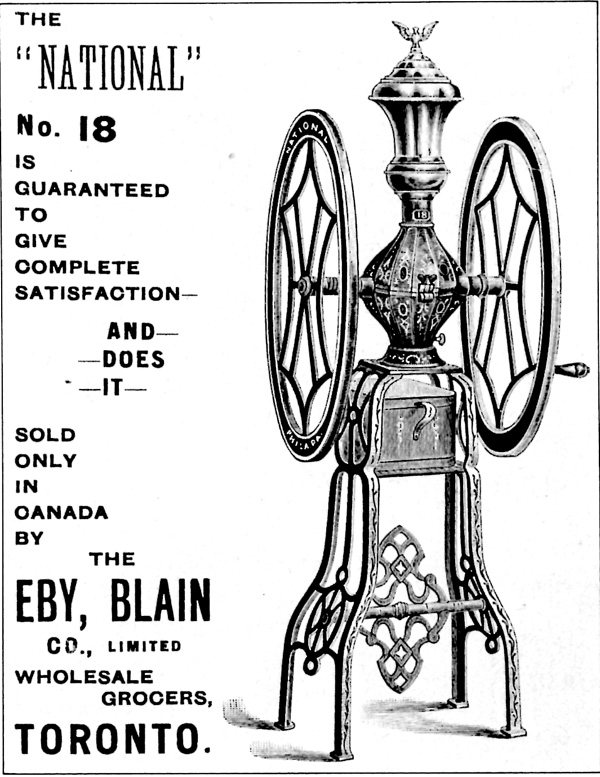

Like biscuits and prepared cereals, much of what had

once been bulk goods in barrels and bins appeared on Dawson shelves in

neatly and uniformly packaged units. Bulk tea appeared in 40- and

50-pound packages. Coffee beans were also available in one-pound tins or

in 25-pound sacks; the beans were ground into paper bags printed with

the retailer's name, as a common method of distribution, and the coffee

grinder never disappeared from the counter. In the photograph of the NC

Company's store, a grinder is barely visible at the far end of the

left-hand counter. While the Canadian Grocer carried

advertisements for "Coles" coffee mills from Philadelphia and "National"

mills (Eby, Blain and Company, Toronto, agents; see Figs. 46 and 47),

smaller countertop models are displayed in the Dawson Hardware Company

Museum; these are examples of the popular "Enterprise" (Enterprise

Manufacturing Company, Philadelphia) and "Swift" (Land Brothers,

Poughkeepsie, New York) coffee mills.57

46 Coffee mill, advertised in the Canadian Grocer in 1903.

(Canadian Grocer, Vol. 17 No. 45 [Nov. 1903], p. 28.)

|

47 Coffee mill, advertised in the Canadian Grocer in 1904.

(Canadian Grocer, Vol. 18 [July 1904], p. 23.)

|

Other goods were still available in bulk form, in

addition to more modern packages. Apples still arrived tightly packed

in barrels, but they were also sold in small tins and gallon units.

While tinned butter was the only kind which arrived in Dawson at first,

cold storage reintroduced the ordinary kind in 14-, 28- and 70-pound

tubs, cases and barrels.58 Tubs from the east were most often

made of spruce. The tubs manufactured by United Factories in Toronto had

lids firmly pressed on and four encircling hoops to hold them together.

For protection from prolonged contact with the wood, the butter was

wrapped in clean cloth and then in a salt and water paste. Cheese, like

preserved butter, was most popular in the north in its prepared and

packaged form.59 MacLaren's cheeses were especialIy in

evidence, in case lots of 24 small jars or 12 medium-sized ones (Fig.

48). Stilton, "Oregon Cream," "Genuine Swiss," "Young America" and

"Ontario Twin" cheeses are recorded in 1905 market reports at various

prices per pound;60 the forms they came in, however, are not

known. They were probably sold in boxed form, for at the same time the

Canadian Grocer urged its subscribers in the cheese trade to

avoid the false economy of cheap boxes.61

48 Three of McLaren's cheeses.

(Canadian Grocer, Vol. 19 [Feb. 1905], p. 14.)

|

Rice and flour of all kinds were traditionally put up

in 50-pound sacks, an especially convenient size for outfitting. This

size continued to be standard. In the NC Company's photograph, however,

the sacks on the left-hand back wall appear to be considerably

smaller than 50 pounds (Fig. 39), but they may have contained dried peas

or tapioca, which came in 10-pound sacks. Sugar was available in a wide

variety of forms, each with its corresponding pack. Granulated sugar

came in units of 20, 50 and 100 pounds; lump sugar came in barrels and

half-barrels; bar or loaf sugar came in 25- and 40-pound packs, and

pulverized sugar came in 25- and 100-pound barrels. Barrels and hogs-heads

of brown and white granulated sugar presented a common problem to

the merchant. The contents became so hard over a period of time that a

sugar augur had to be used to loosen the cemented mass.62

Syrup and molasses rarely arrived in the Yukon in

large kegs. "Imperial" and "Log Cabin" were both popular brands of maple

syrup (Fig. 49) and came in both 1- and 1-1/2 pound and in 5-gallon

tins. Vinegar was still available in large quantities. Most preserving

companies retailed their own vinegar in units from 1 gallon to 24 or 36

quarts. Pickled goods of all kinds were packed in wooden barrels or

smaller kegs (Fig. 50). Pickled mackerel, herring, pigs' feet, hocks

and beef, as well as the common pickled fruits and vegetables, were to

be found in this form. "Heinz" advertised a number of packing units.

Their pickles were put up in 1-, 2- and 3-pound kits, 16- and 30-gallon

barrels, 5- and 10-gallon kegs and (of course) in bottles of less than

a quart. Their motto, "57 Varieties," could be adequately vouched for in

any large grocery department (Fig. 51). Salt came in barrels, as well

as gunnies of 3, 5, and 10 pounds. Olive oil was marketed in quantities

ranging from a pint to 12 gallons; French mushrooms came in sacks of as

much as 100 pounds, and lard came in tubs of any size from 3 to 50

pounds.

49 "Log Cabin" registered label, 1900.

(Department of Consumer and Corporate Affairs, Trade Marks Registry.)

|

50 "Ozo" pickles, 1904.

(Canadian Grocer, Vol. 18 [July 1904], p. 56.)

|

51 Five of the 57 varieties, 1904.

(Canadian Grocer, Vol. 18 [Oct. 1904], p. 146.)

|

While the shipping and retailing of products in bulk

was maintained in various lines, these too were being gradually

converted to packaged and name-brand items. Jams, jellies, sauces, olives,

mustard and other condiments were packed into jars and tins (and, in the

case of jams, pails) which varied from half a pint to 5 gallons in

volume (Fig. 52). Baking powder came in standard-sized tins of 4, 8, 12

and 16 ounces and 2-1/2 pounds. Fruit and vegetable tins were usually of

the 1-, 2-, 2-1/2- or 3-pound size. Breakfast cereal boxes contained

either 1 or 2 pounds, while tins of cocoa were usually only a quarter or

a half pound (Fig. 53). Tinned meats were generally sold in 1- and

2-pound quantities, as was condensed milk and cream.

52 E.D. Smith cherry preserves (probably one pint), 1905.

(Canadian Grocer, Vol. 19 [March 1905], p. 55.)

|

53 A half-pound tin of cocoa.

(Canadian Grocer, Vol. 18 No. 1 [January 1904], p. 7.)

|

With the packaging of staple goods in standard units,

the standard case lot followed as a natural consequence. This provided

a measure of efficiency in shipping, storage and wholesaling. In fact

the photograph of the NC Company grocery department (Fig. 39) shows that

packing cases were brought into the store and incorporated right into

the displays. The transaction of moving goods from warehouse to shop

was much easier than it had been in the days of bins and scoops. The

case lot could be opened for display and small purchases or it could be

sold as a unit, as often happened in sales to miners from the

creeks.

The standard case lot of cereals consisted of 36

boxes of either one or two pounds each; biscuits were packed in lots of

four dozen 2-pound boxes. A case of cocoa had 24 half-pound tins; a

case of baking powder was 36 8-ounce tins or 12 16-ounce tins or 6

2-1/2-pound tins. A case lot of butter usually contained two dozen 2-pound

tins, while one of condensed milk comprised four dozen one-pound tins.

Case lots of tinned fruit and vegetables were usually made up of two

dozen of either the 2- or 3-pound size. T. Eaton and Company had a

case lot of half a dozen gallon tins as well (Fig. 54). Dried

fruits, both in Dawson and Eaton's catalogue, came packed in crates

weighing either 25 or 50 pounds (Fig. 55). Tinned meats were sold in a

variety of case lots, usually of one or two dozen of either the 1- or

2-pound size. Whole tins were packed directly into the cases, bottles

were wrapped first in a paper wrapper, often printed with the company's

name; "Lea & Perrins" wrappers had the company's name in blue ink

diagonally across the outside.63

54 Case lots of tinned fruits and vegetables put up by the T.

Eaton Company, autumn, 1909.

(The Archives, Eaton's of Canada Limited.)

|

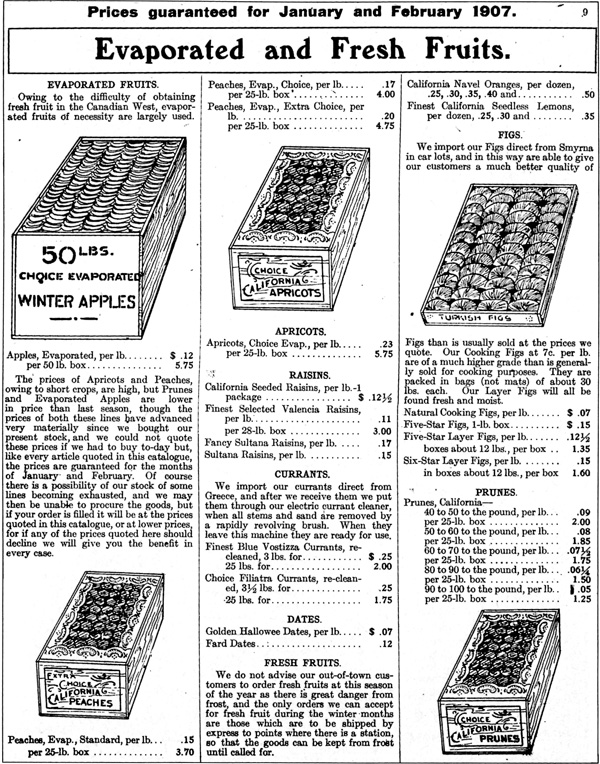

55 Case lots of fresh and evaporated fruits from the T. Eaton

Company, 1907.

(The Archives, Eaton's of Canada Limited.)

|

As F.C. Wade pointed out, one reason for the extensive American trade

with the Canadian Yukon was the progressiveness of its packing industry.

Lighter tin containers, more attractive label lithography, more reliable

packing of hams, cheeses and butter, all had their effect on the

competitive Dawson market.64 As late as 1905 the Canadian

Grocer took up the same issue with Canadian manufacturers who were

hoping to increase their shipments north.65

While increased convenience and tidiness were generally associated

with the transition to packaged foods, the quality of the food could be

affected too. A brief look at food standards has been taken above, but

many years after the outfitting rush, both retailer and consumer were

still plagued with adulterations and substitutions. While substitution

tended more to cheapen the product and add to its weight rather than to

introduce harmful substances, the common malpractice was gradually being

brought to public attention. Packaging had certainly cleaned up many

products, such as rolled oats, by sealing them off from the dirt which

naturally accumulated in any general store, but the practice of

additions and substitutions in the canning and packing industry was

still far from being eradicated.

A Canadian Grocer report in 1904 showed that of 74 tested

samples of jams and jellies, only four were found to contain nothing

more than fruit, cane sugar and water. The rest contained varying

amounts of turnip, glucose, coal tar, dyes and salicylic acid (the last

two of which are noxious).66 The same report showed that 100

out of 188 samples of various spices contained stone husks, shells,

sweepings, charcoal, hair or dirt. The following common adulterants were

singled out:

|

| Original | Adulterant |

|

| olive oil | cotton seed oil |

|

| maple syrup | brown sugar |

|

| maple syrup | glucose, sugar, water |

|

| pepper | stones, pulverized nut shells |

|

| jellies, jams | apple jelly, artificial colouring |

|

| baking powder | terra alba |

|

An early issue of the Grocer told of chicory in coffee (a

practice which was widely accepted at the turn of the century), acid in

vinegar, starch in mustard, old sugar covered by new and boric acid in

butter.67

Of course not all food complaints could be passed

over as the responsibility of the manufacturer. Laura Berton tells of a

well-known Dawson fruit dealer who "for a fabulous price . . . could sell

you a deep box of fruit, the top layer perfect specimens, and all

underneath rotten, with a smile of angelic sweetness and a gracious

phrase of broken English."68 The trials of shipping and

storing perishables were apt to have adverse effects on those foods. One

lady complained of finding five or six bad eggs after paying $2.50 for a

dozen.69 The taste of the eggs could be completely ruined by

poor packing procedures. For example, if jack pine was used for the

crates instead of basswood or elm, damp weather caused the eggs to

absorb a very nasty odour. Egg crates, the ever-watchful Grocer

warned, had to be well-constructed and ventilated, since breakages

could release a dreadful and permeating smell.70 Cheese boxes

needed continual inspection, especially in warm weather; unless they

were cool and dry, gases could form. When this happened, the merchant

was instructed to use a wire to poke a hole in the cheese to give vent

to the gas. Mould had to be scraped off, and the surface rubbed with

sweet oil.71

The average Dawson resident was cautious about what

he bought, not because he was an overly fussy customer, but because his

experiences with frozen outfits, tinned or cold storage foods, goods

shipped over several thousand miles (not to mention his encounters with

poorly packed or adulterated products) had made him acutely skeptical at

the grocery counter. While the merchant could never wax too descriptive

in his newspaper advertisements, he did recognize the prevailing

insistence on purity and worked his slogans around that demand.

"Warranted perfectly pure," "everything we sell is guaranteed" and "no

goods are sold over our counter until we have personally

sampled them and found them to be good" were common phrases in

newspaper columns. Some merchants were more blunt. The AC Company in 1900

advertised "Bro-man-get-on" as "a delicious dessert jelly, absolutely

pure ... no injurious adulteration." This store refunded money

to the dissatisfied customer as a policy,72 as did the Ames

Mercantile Company. Weld's Minnesota Grocery claimed in 1902 that

"adulterations are barred out and pure groceries are sold at very

moderate prices."73 In general, goods were advertised as

fresh, palatable, nourishing, wholesome, good, of the finest or highest

grade — or any combination of these.

Even in making his actual purchase the consumer had

to be careful, although the phasing out of bulk goods alleviated much of

the need for surveillance at the scales. The Dawson customer had added

cause for caution, at least as long as he was dealing in gold dust. The

understanding which existed between merchant and customer in this

ritual has been discussed in the preceding chapter. The eventual

insistence on hard currency as tender also contributed to the reduction

of this worry. In the early days of Dawson trade, the scales — for

dust and for goods — were among the most conspicuous features in a

commercial establishment, for a variety of goods from beans and

blankets to soap and candles was sold by the pound.74

Romantic though they may have been, the gold scales were the first to

go. They were replaced by one product from an up-and-coming company in

Dayton, Ohio, which was already working its way into many a North

American store. In 1898 the National Cash Register Company was retailing

its wares at $50 to $70 in Vancouver.75 Two years later,

McLennan and McFeely were selling these machines to any merchant who

wished to modernize his business.

The Canadian Grocer thought that the efforts

of even the best-intentioned merchant to present his goods in an

attractive fashion would be totally wasted if he did not ensure that

the interior of his store was brilliantly illuminated. By 1900, however,

a large number of Dawson firms were able to convert to electric lighting

using the power supplied by the Dawson Electric Light and Power Company.

In January, the AE Company had 50 lights installed, the SYT Company

had 40 and the Ames Mercantile Company had 20. Rowe and Townsend

(cigars and tobacco), the Melbourne Annex Lunch and the Criterion Hotel,

as well as several other hotels, offices, homes and stores on Second

Avenue, were also among the first to convert.76 Two large

corporations had already hooked up their own electric lighting.

Most Dawson stores were dependent for their large,

centrally located stoves, which (naturally enough) became the social

focus of the establishment. The larger department stores could not rely on

this method of heating for their huge retail outlets. Many of them

turned to the steam heat generated several blocks away at the Yukon Saw

Mill. The old AE store, which became the hardware department of the NC

Company, got its heat from one 100-horsepower and two 75-horsepower

boilers. The connecting pipe was wrapped in asbestos and placed in a

12-inch box packed with sawdust. Radiators in every room supplied the

heat. The company could claim proudly that they needed not one single

stove.77

One important aspect of the store's immediate appeal

to customers was the way it smelled. While the merchant had probably

grown accustomed to the olfactory jungle in which he worked, he had to

take care that the total effect was not overwhelming. The

Grocer suggested that foods emitting the most powerful odours (cheese and

pickled goods, for example) be kept near the rear, that dried fruits be

covered, that confectionery be kept under glass and that the sugar be

checked regularly for melting and souring around the wood. At least one

Dawson grocer discovered that, if he roasted his own coffee daily, the

pleasant aroma would manage to dominate all the others.78

Food was not necessarily the only concern of the

grocery and provisions merchant. T.W. Grennan, as has been shown,

carried a considerable stock of household supplies; Germer stocked

tobaccos — although the competition from confectioners and

tobacconists must have been stiff. The following was considered to be a

full slate of the household items offered by one merchant in 1899:

stoves and ranges

kitchen utensils

wringers

clothes pins

potato mashers

wash boilers

flour sifters

muffin tins

portable forges

stove furniture

knives and forks

wash boards

rolling pins

coffee mills

tubs and pails

lemon squeezers

cork screws79

While these items were more in the line of the

hardware merchant than the grocer's, the latter stocked everything

possible in household hardware equipment. The Dawson Hardware Company

Museum contains a "kitchen reminder" issued by Ahlert and Forsha

grocers. It contained such useful items as alum, blacking, blueing,

lamp wicks, lye, stove polish and washing powder.

The appearance of rubber boots in the middle of the

NC Company's grocery department (Fig. 39) is something of a mystery,

given a department store which had a section exclusively devoted to

Klondike clothing — especially since goods and clothing were among

the earliest specializations in Dawson business. Newspaper

advertisements placed by such clothiers as J.P. McLennan, Sargent and

Pinska, Oak Hall Clothing, Hershberg and Company and Red Front Store

were consistently prominent.

The most fundamental truism of Dawson business was

that prices were exceedingly high, both on the wharves in 1898 and in

major department stores a decade later. At this point the basis of the

problem should be fairly clear. Appendix J has been compiled from the

numerous references which had been made to the price of commodities over

the years. Many of these were accompanied by complaints; many more were

included in letters to shock the folks at home. A cursory study of this

appendix brings a number of trends to light. The most evident is the

monstrous gap which separates Dawson's retail prices from those in

outfitting centres or in the Eaton's catalogue. The analysis of

shipping and distribution conditions already given justifies to some

extent Dawson's comparatively exorbitant prices. An indirect effect of

long-distance shipping on prices was the need for Dawson's merchants to

bring in the highest quality and most climate-resistant goods. Another

way of looking at the same set of circumstances was to observe that,

with freight rates so high, it never paid to bring in anything but the

best.80

Another trend made obvious by Appendix J is that by

1907 prices had dropped considerably. Consequently, in some lines

(especially canned fruit and vegetables) Dawson prices appeared to be

nearly competitive with those in Eaton's catalogue. Explanations for

this phenomenon are various. In general, the entire mercantile

structure had been adjusted by 1907 to fit Dawson's population

comfortably; that is, a settled trade operation was able to predict and

provide for the needs of a more stable population. There were particular

factors involved as well, including the reduction of rail rates and the

insistence on cash or short-term payment — changes which created a

more suitable system for the businessman dealing in the modern business

world. The character of the merchant himself was also a consideration,

for everyone agreed that the boom days of speculation and sudden,

immense profits had come and gone. In these and many other ways, Dawson

was taking on the appearance and character of any contemporary Canadian

town.

Nonetheless, the prices charged for staples after

1903 were in no way readily accepted by Dawson's citizens. "You can buy

as handsome things here as in San Francisco or New York, if you don't

mind the price," one visitor wrote coolly,81 but Dawsonites

themselves could not afford to be so nonchalant. From all sides came

repeated criticism that merchants, like landowners, refused to lower

their prices in keeping with the general depressing effect of falling

wages. There were, of course, instances — usually corresponding

with general shortages, such as that felt over the winter of 1899 —

when merchants were actually accused of cornering the market and

deliberate price manipulation.82 During a suspected meat

combine in 1900 the Dawson Daily News took up the cause of the

"labouring classes" who could not afford the $1 and $1.50 per pound

which was being charged for meat, and whose families, it was argued,

hardly received enough nutrition from the cheaper moose and

caribou.83

The comparative price chart (Appendix J) has been set

up in such a way as to bring out one striking pattern of Dawson prices,

seasonal variation, for the years 1897, 1902 and 1905. Without exception

winter prices are higher during these years. The winter of 1897 (the

"starvation winter") is an especially dramatic example of this

phenomenon, and the price of flour most accurately reflects the pattern.

As winter drew to a close, scows of provisions were dragged over the ice

or were sent to Dawson immediately after breakup; the market broke, and

prices returned to normal. The price of flour, for example, dropped to a

startling low of $2.00 per 50 pounds.

It is difficult to follow the sensitive reactions of

retail prices to yearly market fluctuations. For instance, the end of

the winter might mean that one line of goods (Carnation cream, perhaps)

had been sold right out while overstocked canned goods, such as

vegetables, were selling at rock-bottom prices in an attempt to clear

them out before the arrival of fresh goods over the ice and the summer

pack of canned goods. Such was the case in April 1902 when the Dawson

Daily News declared that "staples are cheaper than ever in the

history of the country,"84 and commission grocers were

practically giving their stocks away. The arrival of goods over the ice

from Laberge did much to re-establish equilibrium in the market. By the

end of May and June, prices in fresh goods and perishables were as low

as they ever would be.

This basic pattern was played out annually. Once the

structure had been established, improved and stabilized, once the city's

tastes and needs had been formed and recognized, and once the number of

participating merchants had reached a level commensurate with the

reduced population, the machine was virtually self-perpetuating. As

Dawson settled into its respectable middle age, its customers resigned

themselves to the constant features of northern trade. Clark's "Ready

Lunch Beef," Borden's "Eagle Brand" milk and the ubiquitous canned

fruits would be with them always. Those who carried such commodities

inside as part of their outfits had not been aware at the time of the

precedent they were setting. Years later, if they were still in Dawson,

they had no doubt resigned themselves to a northern diet which was, at

best, tinned and boxed.

|