|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 26

Grubstake to Grocery Store: Supplying the Klondike, 1897-1907

by Margaret Archibald

Mercantile Mosaic: The Men and their Methods

The swampy streets of Dawson had been turbulent, in the summer of

1898, with the activities of Everyman the entrepreneur, with his

swapping, bargaining, peddling, profiting or losing, and ultimately with

his selling out. In such a trade there was little to distinguish the

buyer from the seller. A certain common spirit of adventure and

enterprise did, however, exist; one which in most cases understood quick

profits better than patience and planning. Nevertheless, an attempt to

single out and identify The Dawson Merchant from the maze of active and

peripheral participants results in a dilemma. The problem applies only

to the period during and after the gold-rush, for the identity of the

river trader of the pre-rush Yukon River commercial empire is very well

defined indeed. Jack McQuesten represents a legitimate stereotype; he

was the enterprising, trusting but astute frontiersman who differed

little in character from the prospector with whom he did business.

After 1898 the stereotype blurs. While the mercantile procedure was

definitely more structured and more rational in these years than it had

been before the gold-rush, these factors do not make it more conducive

to generalization. Instead, the group in question becomes more complex.

Dawson merchants have, in the previous chapter, been introduced as a

cohesive group with a known hierarchy and sphere of influence.

Nevertheless the whole was far from uniform; great variety and

individuality prevailed among its membership and within the community

bond.

Consolidation, the unifying force which was considered necessary to

ensure Dawson's commercial survival in the 20th century, was at work

during the period in conjunction with another influential trend, one

which was more a part of 19th-century mercantile behaviour. This trend

was specialization. In the early years of the new century Dawson

merchants were engaged in surprisingly narrow fields of endeavour. This

in itself bespoke a maturing urban population. The general trader in

provisions, dry goods, hardware, feed and livery had indeed been the

predominant figure of both the rural and mining frontiers, but after the

initial scramble for and distribution of provisions in 1897-98, this

kind of small-scale general trade was no longer the rule in Dawson.

After all, once the railway had been completed in 1900, the city no

longer considered itself a remote outpost. In 1899 advertisements

exhorted residents to "avoid the old style or back-woods trading" by

shopping in one of Dawson's better-appointed department

stores.1

The general merchant was still visible in the Klondike, but the

typical role (as defined by the rural country storekeeper or frontier

river trader) had altered considerably. After 1898 the trader and

general outfitter on the creeks probably conformed most closely to the

19th-century image. In many creek camps a single man looked after the

general store, roadhouse, stable and post office. While his tasks were

varied, he and his store were not necessarily the focal point of the

community. In the context of the Klondike's cosmopolitan and, indeed,

sophisticated population, neither was he necessarily the most travelled,

the most experienced in the ways of barter, nor the most versatile man

in the community, as the country storekeeper was reputed to have

been.2

In Dawson itself, the term "general merchant" no longer evoked the

trader or country storekeeper. City directories often applied the term

to individuals who did most of their trade in a diversity of dry goods.

The large multi-purpose or commercial companies, whose lines actually

did cover the range of products traditionally carried by the general

merchant, had from their infancy more resembled the modern department

store. Business was conducted on several floors in such varied areas as

hardware, men's and women's furnishings (clothing), groceries, drugs,

tinware and stoves, china and glass. All these were overseen by managers

and superintendents who directed a number of clerks, salesmen and

saleswomen, warehousemen, weighers, cashiers, book keepers and

stenographers. In 1902 the NC Company had 65 employees and the NAT&T

Company had 31.3 Hardly a classic example of the general

store! Among Dawson's floating merchant population there were, however,

dealers who were general merchants of the traditional sort. These

traders usually operated for a summer season only, and none of them

remained in the mainstream of Dawson's commerce for long.

The merchants who ran well-stocked shops carrying one specific type

of goods were far more noticeable in terms of advertising, promotional

photographs and newspaper articles, and far more representative of the

variety to be found in the business community. In 1902, for instance,

the Dawson consumer could obtain fresh poultry or "fresh eastern

oysters" from any of 16 local meat markets. A total of 27 retail grocers

were in town that year, but many of them were fairly specialized. W.A.

Hammell and Avery's Grocery had acquired reputations for stocking more

goods than the common everyday commodities. "Fancy goods" was the term

they used to describe them. T.W. Grennan was known for his large supply

of household goods and William Germer for his competitive tobacco

counter. If the customer wanted "Armour" meats, John H. Hughes was the

agent; if he was looking for "Swift's", N.P. Shaw and Company's store

was the place to go. Grocers Darby and Schink specialized in baked goods

from their German bakery next door, while M. Des Brisay and Company

concentrated in complete grocery outfits. The North End Grocery prided

itself on its coffee (roasted fresh daily) and the South End Mercantile

Company had a variety of Norwegian delicacies including herring,

sardines, fishballs and anchovies.4

While several grocers dealt in butter, eggs and cheese, there were by

1899 five independent dairies. For those of Dawson's citizens who craved

such luxuries as sweets, fruits and ice cream, there were from the

earliest days stores to satisfy such particular appetites. The number of

confectioneries in the city grew to 13 in 1902. These, along with the

many similar establishments which sold tobaccos, cigars and cigarettes

in addition to candies, comprised a total of 25 shops dealing in

delicacies, treats and specialty items which had once been the

prerogative of the general storekeeper. One of them, Zacarelli's, became

Dawson's most luxurious palace of self-indulgence, dealing in

stationery, ice cream and a full complement of current magazines as well

as in bonbons.

Sargent and Pinska, Hershberg and Company, J.P. McLennan and (later)

Oak Hall Clothing seem to have been the most popular men's clothing

dealers and had full stocks of up-to-date "nobby" fashions for the

northern gentleman. By 1902 there were 15 businessmen and women catering

solely to the women of the city (who had, by this time, increased in

number and respectability). They offered ladies' clothing, millinery,

dressmaking and hair dressing services.

Hardware, like groceries, was a singularly successful field of

endeavour in the Klondike. At first most miners and new residents had

been supplied from basic stocks of shelf hardware — largely an

extension of the types of tools which had been contained in the average

outfit (see Appendix L, below). It was not long before more

domestic tools were required, as were those items of heavy hardware and

machinery needed in the evolving mining industry. By 1903 Bob Bloom and

Charles Kaiser were among the few who still restricted themselves to

general shelf hardware. By contrast, George Apple's Pioneer Tinship, the

Tacoma Hardware Company, the Dawson Hardware Company and "Mc & Mc"

were focusing their efforts on producing their own stoves, tinware and

pipe-fittings. F.G. Whitehead specialized in lamps, D.A. Shindlar in

bicycles (commonly called "wheels"), and Brimstone and Stewart in

furniture and undertaking.

While Dawson was soon rid of the diseases which had plagued the

pioneers of 1897 and 1898, the average resident still had to consider

his own well-being. A versified play on the equation of "health" and

"wealth" exploited his concern in a popular form of advertising for

patent medicine, both inside the territory and out.

With this all-important and universal goal in mind, drugstores were

abundant and prosperous in Dawson. There were eight such firms in 1901,

of which Cribbs and Rogers was the largest. As well as filling

prescriptions, these drugstores provided an other source of such "staple

and fancy sundries" as cigars and sweets.5

With the possible exception of fresh meat and dairy products, all the

foregoing types of goods were available from the complete stocks of the

NC Company, the NAT&T Company, the Ames Mercantile Company and Ladue

and Company, whose claims to excellence were based on their ability to

fill the needs of the family table, the prospector's cabin and the

mining camp in both essential and luxury items at reasonable prices. Yet

these alternatives did not fulfill all the demands of Dawson's consuming

population. By 1899 only one-fifth of the city's population was

women,6 and despite the influx of wives in the new century,

Dawson's customers remained predominantly male and single.

Understandably, their need for entertainment was treated as a highly

promising market.

In this field, entertainment merchants held their own as successful

and respected members of the commercial fraternity. The restaurant and

saloon business was booming. According to Major H.J. Woodside, 50 per

cent of Dawson's residents, even as late as 1901, kept house only as a

place to sleep; daily they filled the city's 33 restaurants for the

standard $1 meal of pork and beans, bread, pie and coffee.7

As consumers of large quantities of food, these restaurants were

undoubtedly valuable clients of the large wholesale grocers.

A similar bond of interdependence existed between "respectable"

businesses and dance halls. While the moral attitudes of the first group

toward the commerce in pleasure associated with the second went

unrecorded, their single-minded opposition to the closing of dance halls

in 1902 was another matter. A petition bearing the names of many of the

pillars of the business community clearly illustrates the close

relationship between these merchants and the pleasure palaces. Not only

were these dance halls, concert halls, theatres and their employees good

customers, but a certain amount of their brisk trade tended to be

deflected into nearby shops.8

Liquor was another product essential to the Klondike way of life,

and, to some minds, one of the most profitable. At first the procedure

of licensing premises for the wholesale distribution of liquor had been

corrupted by the availability of black market permits. The fines levied

on non-permit-holders were regarded by many establishments only as

predictable working expenses.9 By 1902 the schedule of

license fees for the territory was as follows:

| A. — Per Annum |

|

| For wholesale licence | $1,000 |

|

| For hotel in Dawson | 700 |

|

| For hotel in Klondike City, Whitehorse or Bonanza | 500 |

|

| For hotel at any other point in the Yukon Territory | 250 |

|

| For saloon in Dawson | 1,000 |

|

| B. — For Season |

| For steamboats | 150 | 10 |

Lord Minto, on his trip through the city in 1900, hazarded a guess

that every third house was a saloon.11 A year later there

were still 23 of these establishments. Despite Dawson's growing

respectability as wives and family men asserted moderation, the number

barely dwindled over the years. There were 16 saloons operating in 1905.

These saloons, along with some restaurants and the city's many

confectioneries, shared the cigar and tobacco trade, a lucrative one

indeed. Tobacco had been regarded as a staple from the days when even

the most spartan of prospector's outfits contained enough plug to make

the long winter bearable. The Canadian Grocer's exhortations to

grocers to keep a well-stocked tobacco counter were of no avail in

Dawson, where that line of business had fallen into more specialized

hands.

The consumption of liquor was aided by a number of merchants who

dealt in wholesale wines and spirits. The AC Company, the NAT&T

Company and the Ames Mercantile Company probably carried the largest

stocks. In 1898 the AC Company was authorized to bring in 10,000 tons of

liquor in exchange for a $25,000 license fee and another $60,000 in

customs and revenue duties.12 By 1901 only the two largest

among the mercantile companies retained their licenses in wholesale

liquor. The remaining trade was divided between Gandolfo (one of the

enterprising fruit dealers of 1898) and Binet Brothers at the Madden

House Hotel.

Dawson establishments were as varied in size and status as they were

in the kinds of business they carried on. Again, loose categories may be

drawn up, based on the amount of control exerted on the whole process of

purchasing, shipping, storing and distributing. In determining

comparative status, the distinctions made in the previous chapter

between wholesale-retail companies and the smaller retail establishments

which depended upon them are still useful as well. By compiling

information from city directories for the years in question, a

comparative list of the number of people employed by various businesses

can be formed. Where more precise information as to capital and assets

is not available, this list is a rough indication of business size.

However crude the method, the results obtained reveal that the ten

largest employers and Woodside's list of the eight controlling firms

correspond remarkably closely (see "Metropolitan Airs: Dawson

from 1899 to 1903" and Appendix E). It also gives a fair indication of

those merchants who were clearing enough profit to hire help, separating

them from the third, more transient group of traders.

The large or controlling firms were lively promoters of Dawson's

trade, both wholesale and retail. Their concern with the future of the

community stimulated an interest in local elections to positions of

prestige and authority, an interest which encouraged them as a group to

play a significant part in local politics. Both as employers and as

major investors they were able to exert an influence over the scope of

candidates' policies. In some cases they entered the political fray

themselves. H.C. Macaulay of Macaulay Brothers, wholesale importers, was

one such; he was elected the first mayor of the newly incorporated

city.13 In the following year the mayoralty race was won by

P.H. McLennan, the popular "Dawson-Vancouver Hardware King" and resident

proprietor of McLennan and McFeely. His closest contestant was Thomas

Adair, better known as one of the owners of J. and T. Adair, general

merchandising, hardware and pianos.14

Local journals sometimes made mention of the various activities of

leading merchants. While the names of smaller establishments rarely

reached the columns except in advertisements, social notes frequently

contained items about the more important proprietor when, for example,

he left the north for the outside on a business tour of distributing

houses across the continent and abroad. The Dawson Hardware Company,

McLennan and McFeely, Sargent and Pinska, the AC Company, the

Seattle-Yukon Trading Company, the Ames Mercantile Company and the NC

Company could evidently afford the time and expense to set up their

orders in this way.15

Occasional bits of information exist which record the careers of

members of this group as they participated in related commercial

ventures. R.P. McLennan (dry goods) and H.T. Roller (resident manager of

the SYT Company) both held seats on various boards of directors in trust

companies, stage transfer lines and power and telephone

companies.16 J.R. Gandolfo, who was originally known for

being the first on the Dawson market with his citrus fruit in 1898, was

in later years equally well known in real estate as one of Dawson's more

cunning investors.17

In addition to this group, a second category of merchants existed, a

smaller group which played a constant but less visible role in the

community. This category roughly encompasses the city's variety of

retail firms which, although they competed with the larger firms for the

retail trade, were usually staffed only by the proprietor and one or two

assistants. The second part of Appendix E, showing those firms employing

fewer than three assistants (1901-03), covers the majority of this

group. There is little information about their personnel and

operations.

Although they were exceptional in the fact that theirs was not a

predominantly retail trade, Dawson's wholesale and commission merchants

should also be noted. The details of these businesses remain vague, but

newspaper advertisements reveal that they stocked their warehouses with

complete lines of goods over a wide range. Hay, feed, flour, eggs,

stored vegetables and canned milk might all come into their purview at

one time or another. They purchased surplus consignments and goods

brought in over the ice and stored them for resale and speculation.

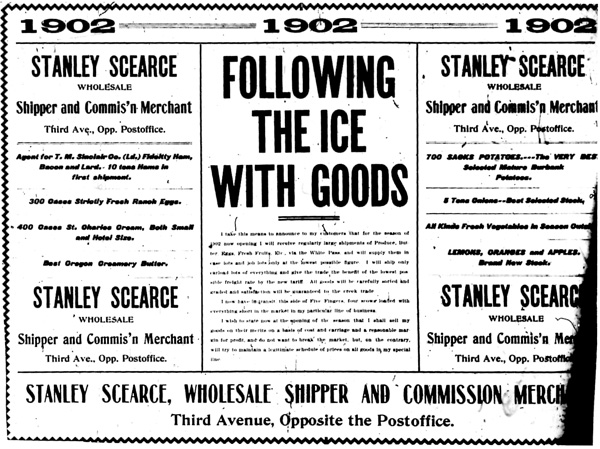

Barrett and Hull, Peter Steil (later Steil and Mullen), Stanley Scearce,

and Cheney Kniffen and London were Dawson's largest commission merchants

in the period 1901-03. Stanley Scearce's advertisements in the Dawson

Daily News in 1902 reveal the business on its grandest scale (Fig.

36). Although they were neither as completely nor as consistently

stocked, nor as responsible for the quality of the goods sold as were

the commercial companies, these commission merchants were nonetheless

their rivals.

36 The advertised stock of the versatile commision merchant.

(Dawson Daily News, 17 May 1902, p. 8.)

|

The third group (if it can be so-called) of Dawson merchants in this

period included its most colourful and certainly its most controversial

members. For the purposes of this work, these merchants may be loosely

described as unspecialized self-employed traders who operated without

permanent mercantile establishments. This includes men who were either

engaged in Dawson trade on a transient basis or who, if they took up

residence, spent (as a rule) no more than one season in the town. It

encompasses the transient trader — the mistrusted river or scow

pedlar, treated by the majority of contemporary permanent merchants as a

thorn in their sides and a universal scapegoat. While they were not

similarly mistrusted, the local small traders who were to disappear

during Dawson's belt-tightening after 1902-03 may also be placed in this

third category. The identity of such a trader is marked by his absence

from newspaper advertisements, photographs and business directories.

In retrospect, it would seem that these transient and local traders

shared a particular function: they filled the gaps and shortages which

were a perpetual feature of Dawson's market. These gaps were especially

visible in the grocery trade, more specifically in fresh fruits and

vegetables. In season and out, Dawsonites could never get enough of

these commodities.

The Dawson Daily News, a faithful voice of the stable element

of local business and a vehement advocate of commercial progress, spared

no adjectives in its condemnation of the transient trader:

Unscrupulous . . . unprincipalled curbstone dealers . . . with

office in their hats and the half of whose capital consists of an

immaculate nerve and an unequalled audacity. . . . The same chap one

meets on the street today with a lot of moccassins for sale, "go

sheep", tomorrow peddling out stale eggs and the next day probably

selling socks or cheechako spirits. . . . They are a pest to the

community and a parasite to the legitimate storekeepers, who have

hundreds of thousands of dollars invested in buildings and stock, and

yet who are brought into competition with these people, many of whom

have not even a six by eight shack wherein to do

business.18

These traders were notorious for their evasion of fees and taxes and

for their practice of passing one small rented building from hand to

hand as they took turns going outside for more cargo.19 As

early as 1899 license fees were imposed on transient traders, but in

1902 the government of the newly incorporated city raised that fee from

$150 to $500.20 The imposition and strict enforcement of such

fees must certainly have discouraged the transient element in Dawson's

business community.

The yearly advent of the scowmen, as these transients were generally

called, came in late May and early June. They arrived in Dawson along

with the ice floes. Their winters were spent in Vancouver or Seattle

where they gathered goods which were then shipped to be stored at

Bennett Lake, where the anxious goldseekers had waited out the late

winter weeks of 1897. At Bennett they too waited until the ice broke,

and then they set out in small boats for Dawson. Their small craft

navigated the ice-filled Yukon more easily than the larger sternwheelers

which most Dawson merchants employed to transport goods, and theirs were

understandably the first fresh perishables to reach the winter-weary

Dawsonites. Turnover was rapid, and before a trader's presence had been

really established, he was off to bring in a second lot. The speed of

these trips was the secret of their success, for such traders were best

at serving areas where known shortages existed. Such holes had to be

plugged immediately, before the larger companies had a chance to order

such products through regular channels. The trade was, in fact, an

exhausting one, and after a few years of two round-trips each shipping

season, the scowman had probably had enough.

Not every transient trader was denounced by reputable businessmen.

Ezra Meeker was a yearly comer whose arrival was hailed and whose goods

were announced in the newspapers.

Meeker was one of the traders who set up semi-permanent quarters on

which he paid taxes and his trader's fee. (The building is still

standing, or so a sign on a small one-storey cabin on Third Avenue

across from Caley's Store indicates.) Meeker's first and most memorable

trip was over the Chilkoot Pass in 1898. His flat-boat arrived in Dawson

with 9,000 of his original 15,000 pounds of vegetables. Two weeks later,

he pulled out with "two hundred ounces of Klondike gold in my

belt."21 Urged on by his hopes of a lifetime's wealth from

Klondike gold, Meeker continued his yearly pilgrimage until April 1901

when his mining properties finally failed. In leaving Dawson for the

last time, he vowed never to set foot in mining territory

again.22

One fascinating feature of the Dawson merchant's history is his

origin: what brought him to the Klondike? And what drew him into the

business of buying and selling in the city? Many who were to become

Yukon merchants had initially entered the territory as goldseekers,

unsure of what form the paystreak would take. Some of these never made

it to a placer creek, realizing along the way that there was a less

heroic but more reliable way of get ting rich. As long as thousands of

others were determined or naive enough to continue the placer quest,

there was money to be made in providing for their survival.

Many a Dawson merchant had his first taste of barter as a

goldseeker-turned-entrepreneur along the famous trail of 1898. The

commercial career of J.O. Drury, an Australian goldseeker, had an

enterprising start when he bought a bolt of ticking, filled it with Dyea

hay and easily sold the product to new arrivals. In 1899 he pooled his

commercial know-how with Isaac Taylor, an Englishman he had met on the

Ashcroft Trail to the goldfields the previous year.23 Since

their original meeting, Taylor had set up a store in Bennett which he

had stocked with collected outfits and an initial consignment from R.P.

Rithet in Victoria, representing an investment of $200.24

Before long, Taylor and Drury had moved to the new railhead at

Whitehorse where the firm has remained ever since. It amalgamated with

Whitney and Pedlar in 1912 and bought them out seven years later.

Like Taylor and Drury, Bob Bloom came to the Klondike in 1898 by the

Chilkoot Pass. Like them, he perceived the possible profit in handling

the redistribution of the tons of outfits on the passes. "Swopping," as

he called the transaction which occurred when the disillusioned sold out

to those who needed more goods to stay on, could lead to a fortune for

the permanent middleman.25 Bloom's first years of business in

Dawson were based on continual "swopping." He supplemented his stocks by

consignments from Victoria and Vancouver, primarily from McLennan and

McFeely. During these early winters when business was slack, he drove

cattle from the coast to Dawson by overland trails.

Charles Sargent and Martin Pinska formed a partnership in February

1899 which marked the beginning of a firm which soon became one of

Dawson's in 1898 (from Duluth and St. Paul, Minnesota, respectively)

their initial interests in the Klondike had been somewhat dissimilar.

Sargent hoped to acquire his wealth through mining, while Pinska came to

Dawson with enterprise in mind. He brought with him a large stock of

furs and opened a waterfront store in September 1898.26

Business was good, and Sargent was persuaded to leave the drudgery of

mining for a more reliable sort of profit-making operation. No sooner

had the partnership been formed than its store was destroyed by the

April 1899 conflagration. The firm relocated on a prominent lot at First

Avenue and Second Street. By that fall Sargent and Pinska had enough

capital to send one partner outside to buy stocks from New York and

Boston manufacturers.

Like Pinska, other commercially minded men regarded the Klondike

market as a worthwhile risk from the beginning. In many cases these men

already possessed a quantity of capital which they determined to invest

in mercantile ventures in Dawson. Some of them directed companies which

dispatched representatives to open branches and extend operations into

the north. (The extension of branch outlets by established west-coast

firms has already been discussed as a factor in Yukon River

development.) Others had no connections with existing companies, but

possessed a large amount of capital which they invested in mercantile

ventures. Both of these types were knowledgeable investors, men whose

experience had led them to anticipate a large profit on money invested

in gold-rush commerce.

One example of an extension of a large company was Parson's Produce

Company, with headquarters in Winnipeg. This firm was, according to the

Nugget, one of Canada's largest businesses. In addition to the

Dawson investment, Parson's had branches in Vancouver, Nelson, Victoria,

Rossland, Atlin and Bennett, British Columbia, as well as in Exeter,

Ontario. The Dawson local manager, H.P. Hanson, had had two years of

experience with the company and had at one point been mayor of Morden,

Manitoba. By the end of 1899 Hanson had supervised the construction of

three new warm and cold warehouses (to replace those lost in the April

fire) as well as a second Dawson branch store.27

A good example of the second type of capitalist was S.D. Wood who,

until he heard the call in 1897, was the mayor of Seattle.28

Wood soon became something of a legend (certainly an example) in

Seattle, for he relinquished his secure post and invested $150,000 in a

Yukon fleet and in stocks of goods and a warehouse in Dawson and five

other Alaskan points.29 He continued to live in Seattle,

leaving the management of his multi-purpose company (carriers and

traders, staple and factory provisions, wholesale and retail, warm and

cold storage and vessel leasing) to H. Te Roller.30 Te

Roller, as previously mentioned, invested in several Dawson concerns

himself. When the SYT Company was sold out in 1900 Te Roller became the

resident manager of the rival NAT&T Company.

Rather than embark immediately on a partnership or invest heavily in

a large consignment of outside goods, many businessmen preferred to

acquire capital and experience in northern mercantile activities by

working as employees of one of the already established firms. In some

cases, the prospective merchant probably sought temporary employment

when he was unable to locate on the goldfields. Before long, he

recognized the potential profit to be gained and resolved to embark on a

commercial venture himself. Appendix E indicates the ample opportunities

offered by Dawson businesses for such apprenticeships. The regularity

with which such apprenticeships occurred is illustrated by several

documented examples among the city's merchant population.

William Clark and W.A. Ryan were both experienced in northern trade

when they opened the North End Grocery in 1900. Both had come north from

Tacoma, Washington, where Ryan had been county clerk and correspondent

for the San Francisco Chronicle, and Clark had been an

attorney.31 Ryan had gained his experience as a clerk in the

AE Company, while Clark's commercial training had begun when he was a

waterfront trader.

Another Dawson merchant, W.H. Hammell, already had acquired some

commercial experience in Montana when he arrived in the city in 1897.

This experience undoubtedly helped him to find employment in the

NAT&T Company shortly after he reached Dawson, and he remained with

the company for the next two years. In August of 1899 he opened a store

of his own, providing staples and fancy groceries for the family home or

miner's cabin.32 The understanding of commercial operations

in the north and his capital, both acquired at the NAT&T Company,

were without doubt the foundation of his operation.

In 1903 a partnership known as Cheney, Kniffen and London appeared in

the city directory as commission merchants, auctioneers and general

merchants with outlets on First Avenue and in Bonanza. Directory

listings for previous years show that these three had been independently

engaged in auctioneering before coming together in a partnership.

One especially notable case of a proprietor who worked up through the

ranks of an established firm was that of R.S. Hildebrand. In 1901

Hildebrand was a mere shipping clerk for McLennan and

McFeeley.33 By 1905 he had bought out the firm's Dawson

holdings.

While Dawson merchants' routes to commercial success varied, there is

one feature of their collective origin which stands out clearly. Very

few of them were Canadians. This fact was exposed in 1899 when the

Dawson Daily News billed Parson's Produce as the only Canadian

firm trading in the Yukon.34 Why the News chose to

overlook McLennan and McFeely as Canadian operators must remain a

mystery, but the data given in Appendix C is a fair indication that

Canadian businessmen were not in the majority. This information has been

compiled from all available references to the place of origin of any

Dawson merchant or business firm. Such references do not abound, and the

final product is, unfortunately, rather meagre. The results, however,

are far from surprising. They merely reflect the fact that Dawson's

population was predominantly American.35

Contemporary newspaper advertising conveys both the quality and

versatility of Dawson's many stores. Weighted as they were in favour of

each merchant's virtues, these advertisements leave one to wonder what

reputation these men did indeed have with their customers.

The newspapers raised their voices in disapproval of business

oversights or malpractices only on major matters which involved the

entire business community. Consistently excessive prices and the

cornering of a particular line of goods were usually the issues in

question.

The NAT&T Company was censured by the Nugget in 1898 for

its supposed irresponsibility and unfair distribution of goods during

the preceding winter's shortages, but when Healey, the manager, was

recalled that September, the fuss died down. Such an outright

condemnation of a single firm was rare. One ardent critic of the

Klondike trade in general was Mary E. Hitchcock, a wealthy American

tourist who had chosen to spend her summer holidays in the Klondike. She

was a connoisseur of fine goods and a more demanding customer than the

average Dawson citizen during the summer of 1898. Few of the firms she

dealt with escaped her caustic commentary: "Between the cheating of the

people from whom we bought The goods, The spoiling and detention

of our boxes by The steamship companies and the Non-responsibility of

the warehouse owner, it is enough to drive one crazy."36 It

should be pointed out that the disorder of gold-rush times was hardly

likely to produce the sort of mercantile habits which Mrs. Hitchcock and

her companion had come to expect in the more genteel commercial centres

of the continent.

In keeping with the many other facets of northern progress, merchants

prided themselves on their maturing business methods. The AE Company

claimed in 1899 to have advanced beyond the crudities of backwoods

trading "where you get what they want to give you in exchange for all

you've got."37 A rather long and highly laudatory newspaper

article on the workings of the AC Company in 1898 praised that firm and

its managers for their attention to order and detail, their execution of

broad-minded plans, their fair prices and their absolute refusal to

exploit the consumer. As the most seasoned of Dawson's firms, the AC

Company was already capable of combining efficiency with elegance in

their operations. Undeniably (the Nugget thought) this marked

"progress towards civilization and its influences."38 As long

as business achieved that most important goal, the Nugget's

reporter could find no reason to criticize.

H.P. Hanson, the courteous local manager of the Parson's Produce

Company, was in turn singled out by the Nugget for public praise

as being one of the most popular men in Dawson because of "certain

straightforward qualities inherent in himself."39 Honesty

continued to be regarded as a virtue in the Yukon trader; the total

dependence of the community on his goods required it to be so. At one

time the trader had reciprocated by allowing almost unlimited credit to

his mining customers. Much has been made of the swamping of the miner's

code by the onslaught of the Klondike rush. Indeed, the kind of trust

which had existed between Jack Mcuesten and his customers would have

been sheer naiveté in the grasping days of 1898 and after. But a

certain amount of faith was still necessary, and Bob Bloom's wife spoke

in retrospect of her husband's "uncanny knowledge of who he can trust

and who he should avoid."40

Part of the price of 20th-century efficiency was the generally

enforced restriction of the once promiscuous credit system.41

The Dawson Hardware Company letterbook of 1903-04 shows that substantial

security had to be presented before opening an account with that firm.

The standard 60- to 90-day period of payment was all that was allowed,

although this does not appear to have been rigorously enforced. Late in

June a company collector was sent up to the creeks to clear up all

unpaid bills.42 His timing was good, since it followed

closely on most cleanup operations and ensured the sudden income needed

by the company to make its own large July payments. However severe the

Dawson Hardware Company's methods seem to be in theory, in practice this

rigorous system was essential to keep a balance. The company was

constantly beseeched by miners for clemency on payments. The company

letterbook is filled with scraps of paper with pencil-scrawled apologies

for late payment: cleanup had been impeded, the paystreak was close at

hand, unforeseen expenses for repairs had delayed other payments —

in short, cash was not available. One letter from a medical doctor-miner

in Dominion Creek starts with the common story of woe; his diggings had

taken him unknowingly away from paydirt and into bedrock —

therefore, no gold. His plea for time is made more complete by his

statement that his own patients were not paying their bills either, and

that he understood perfectly the position of the hardware company. One

roadhouse proprietor explained that August was the month for the renewal

of the expensive liquor licenses, and that as a result he had no cash

remaining to pay his bills.43

As long as gold dust was used as a means of payment, extended credit

was readily available and grubstaking remained a prevalent custom,

Dawson trading ethics were a common subject of discussion. There was a

legendary ritual of completing a transaction; one tossed one's poke on

the counter and pointedly turned away while the merchant weighed out the

amount owing on the purchase. It he so wished, the miner could request

that a respectable store or saloon keeper look after or "bank" his poke

for him.44 An unlocked drawer was allegedly used for this

purpose. (Presumably one avoided the premises of those less scrupulous

dealers who exploited such ceremonies.) In 1899, before the arrival of

official weights and measures from Ottawa, it was reported that no two

sets of scales in town were the same, and that the only reliable ones

were those used by the large companies.45 In most cases, a

certain percentage as a "tip" to the weigher was acceptable to both

sides. It was possible, however, for some swindlers to gain as much as

50 cents on the dollar.

While gold dust was never officially legal tender, its widespread

use as such was unavoidable. The miner paid for his provisions with the

products of his labour in much the same way that the rural consumer paid

for his supplies with crops, livestock or firewood. The custom was

entrenched in Dawson commerce by 1898. In that year, hard currency was

grievously scarce while dust was plentiful enough to be baked (one miner

quipped) into Christmas puddings.46

The AC Company partly solved the currency problem by issuing vouchers

and tokens.47 These were paid out at a specified rate for

contracted work; men selling cordwood to the store, stevedores on the

company docks and store employees were all paid in this way with

vouchers redeemable at the company counters. The policy did not last

beyond 1898 and it does not appear that any other company followed

suit.

The whole issue of the fluctuating exchange rate on gold dust was a

vital one to both merchant and miner. The slightest variation brought

cries of outrage from one camp or the other. The matter was complicated

by two factors. First, each creek's dust assayed at a different value,

varying from $12.50 per ounce on one section of Hunker Creek to $17.50

on another.48 Second, the nearest official assay offices were

thousands of miles away in Seattle. That necessitated initial payments

by the store or bank to the miner, with the promise of refunds if the

gold assayed more than the base value.49

The immediate solution adopted to cope with such an involved

procedure was a streamlined operation whereby a recognizable and

inferior gold dust, called "commercial" or "trade" dust, was circulated

exclusively for local business transactions. This adulterated form was,

of course, worthless, and could be bought from the bank at an

established rate in exchange for the real stuff. The process resulted in

uncontrolled inflation as the value of an ounce of trade dust dropped

progressively in relation to the value of a pure ounce. In 1900 the

ratio stood at $14.50 to $16.00.50 If a case of goods was

worth $16.00 (one ounce of pure gold) it could be bought (theoretically)

for an ounce of trade dust, but, given this ratio, the merchant would be

reimbursed only $14.50. As a result, rather than to assay all incoming

gold to determine whether it was pure or trade assay, merchants simply

went on the assumption that all dust in circulation was impure and

accordingly raised their prices.51

Eventually the market was so inundated with trade dust that the Board

of Trade reacted, announcing that the local exchange rate on all dust

brought to the counter would be $15 to the ounce.52

The placer labourers, an understandably discontented group at best,

were infuriated by this announcement. They feared that the next step

would be the total abolition of dust as a medium of currency. Throughout

this controversy the Dawson Daily News stood squarely behind the

merchants. The guilty parties, the editor claimed, were the mine owners

and bosses who were buying up the cheaper dust and using it to pay their

workers.53 The crux of the matter was the fact that wages

were computed on the basis of one ounce equalling $16, which of course

it did not. A worker paid in this way was bound to feel cheated at any

store where his "$16" ounce was accepted at less than that value.

By 1902, despite the threat among miners to form syndicates and buy

their goods outside,54 the exchange rate for commercial dust

dropped again to $13.50. A list of 36 firms which endorsed this policy

was published. Since virtually every major company in each field was

included, the buyer could do little to stem the tide against

him.55

At the same time as the exchange rate was lowered, the practice of

unlimited credit came under severe strain. More and more merchants

demanded immediate payment. Call it the prospector's code or a backwoods

style of trading, but the old order was being forced to change. The

unwillingness of outside suppliers and manufacturers to make allowances

for what they undoubtedly considered to be an outdated frontier system

is fully understandable. By 1904 most controlling firms in Dawson were

responding to this pressure by insisting on cash payments, even from

their most trusted customers.56 Up until that time, some 70

per cent of Klondike miners had been given credit for eight months,

paying up with the results of spring cleanup.

The cash-on-the-spot demand was more than a bluff on the part of the

large companies, but at the same time they could not deny that the

credit tradition was still, for many miners, a way of survival. Both the

use of gold dust and the extension of credit continued to a certain

extent. Generally speaking, long credit and gold dust payments remained

as regular practice only with the general merchants on the creeks whose

clientele was still almost entirely composed of mine workers and whose

methods continued to vary little from the acknowledged frontier

traditions.

Lowering the exchange rate had the immediate effect of stirring up

the long-simmering complaints against unduly high prices. On this issue

the Dawson Daily News jumped to the defence of the

consumer.57 Like landowners and their own arch-enemy, the

WPYR, merchants were (according to the editor) guilty of failing to

scale down their prices in keeping with the post-boom pattern of

economic belt-tightening. Little wonder, he exclaimed, that clubs were

being formed to send outside for supplies.

During this period the T. Eaton Company began to make in-roads in

the Yukon Territory. Although the exact date on which Eaton's catalogue

first crossed the Chilkoot is neither known nor celebrated, its arrival

in the north marked the beginning of a long-lived association between

the Dawsonite and the Dream Book. Since that time, loyalty to local

merchants has been carefully weighed against the advantage of sending

outside for goods.

Much of the general ill-will felt toward the Dawson merchants and

their position on the monetary question should more accurately have been

directed toward the Board of Trade, the official voice of the business

community, including transport, mercantile, banking and real estate

interests. Organized in September 1899,58 the board played an

especially active role before the incorporation of Dawson. During that

time it was an important lobby to the Yukon Council on such matters as

city improvements. Memorials from the board and reports from its various

members form a substantial portion of Lord Minto's Yukon

correspondence.59 The successive slates of the board's

executive position over the years 1899-1903 were filled by a

well-balanced sample of company directors, real estate brokers and bank

managers.60 The actual impulse needed to deal effectively

with the trade dust problem had come from this body.

Those adversely affected by the policy regarded the Board of Trade as

a dangerous combination designed to keep land and commodity prices

high.61 Merchants were thought to be doubly guilty as each

year they faced additional accusations of cornering the market in

certain commodities. This disreputable practice stirred "the collective

sourdough memory" to recall the grim winter of 1897. Calling it the

"starvation winter" was definitely hyperbolic. The root of the scare had

in fact been indiscriminate cornering, resulting in scarcities of

certain articles and black market dealings in many staples. Ever

afterward, once the rumour of a natural shortage in a certain area

reached public ears, fearful gossip about another such winter

abounded.

In 1899 the Yukon had frozen early, leaving many tons of freight

stranded between Dawson and Skagway. During that fall and winter,

massive manipulation was reported in the markets for rolled oats,

hominy, sugar, Ogilvie flour, butter and potatoes.62 No one

was quite sure where truth ended and rumour began. Some firms were

besieged with orders for 10,000 of a single item. The finger of blame

was pointed squarely at those greedy and speculative "unprincipled

curbstone dealers" who allegedly would not hesitate to deprive Dawson's

poorer citizens. After individual interviews with representatives of the

Ladue Trading and Exploring Company, the AE Company, the Ames Mercantile

Company, the NAT&T Company and the NC Company, the Dawson Daily

News discovered that all leading firms either pleaded total

innocence of the scare or issued public assurances of their full stocks

in all areas and their absolute refusal to sell staples in lots larger

than an outfit. No staple line disappeared entirely and no one starved.

Whether anyone actually made his fortune by the scare remains a matter

of speculation.63 Dawson would never be entirely free of

price fixing of a certain kind. No one would deny the existence of open

competition on one hand, but neither could one ignore the fact that,

when the NC Company published its yearly price list, few merchants in

Dawson were not affected.64

In 1902, again, the Dawson Daily News declared in December

that the Pacific Cold Storage Company, the Standard Commercial Company

and one other firm had the city locked in a three-way meat monopoly. The

main point of the newspaper's criticism was that these firms, not

content with their indisputable wholesale control of the market, had

cornered retail sales as well.65 Dawson residents were not

adjusting to mercantile monopolies without complaints.

Merchants were also criticized for their failure to live up to the

general public's expectations of high-quality goods. Dealers in

groceries and provisions were especially vulnerable to these attacks,

partly because of the shipping risks they had to take and partly because

of the age of adulteration in which they lived. (This particular aspect

of merchandising will be discussed more fully in the next chapter.) The

North-West Mounted Police's health inspection provided a certain

protection. The general efficiency of this unit is not known, but the

Dawson Daily News described in lurid detail at least one

successful raid in 1899. The trader in question had apparently been

doing business up until the moment of his arrest — at which time

the odor of his rotten eggs and tainted meat and fish was likened to

that emitted by a sewer, Examination by one health official showed the

meat to be "ready to walk." When the trader claimed that he was selling

his merchandise as dog food, he was admonished, fined $5 and court

costs, and sent on his way.66

By all indications, the established Dawson merchant enjoyed a

comfortable reputation in the city. Presidents and managers of leading

companies, however they were considered by customers and employees, were

generally respected as men of means and social prominence in the

community. These leading merchants were part of a clearly visible

post-boom elite, identified rather succinctly by Laura Berton in her

witty and perceptive analysis of Dawson's social fabric in 1907. The

event in question is the Grand Opening of the gala St. Andrew's

Ball.

It was led, of course, by Commissioner Henderson and his wife,

followed by the church, represented by the Stringers, the law (the three

head judges and police superintendent) and Mammon (the heads of

companies). The rest of us followed behind.67

As the northern store evolved from the cabin of the self-reliant

river trader of the 1890s to the equally versatile but more elegant

quarters of the department store, its role as a centre of social

activity changed considerably. The importance of a warm, well-lit

gathering place in the life of a prospector needs no further emphasis.

Even in Dawson's heyday, when the cheechako hoards jostled along

muddy Front Street, there was still a need for a central point of

reference where friends could be found, news bartered and (above all)

where word of any new strikes could be picked up, weighed as to

authenticity and acted upon it necessary. The AC Company and the

NAT&T Company, centrally located on Front Street and constructed

side by side in the early summer of 1897, had from the start served as

the agora of Dawson, Both stores opened onto large wide platforms

which overlooked the traffic wending its way up Front Street, steamers

rounding the bend from Whitehorse or Saint Michael, and, just across the

way, the heaving and hauling of merchandise onto company wharves. The NC

Company's verandah was indeed a fine place to spend long summer days

waiting for a steamer, waiting for a strike, waiting for a stage bound

for the creeks. In the early days of Dawson-Bonanza freighting, these

companies were the arrival and departure points for various stage lines.

There, without doubt, the pulse of the boom town could be felt daily.

The AC Company's platform and the post office were the places to locate

a long-lost friend, partner or husband. Stories of day-long lineups at

the post office would seem to indicate that the crowd on the AC

Company's platform probably had a better system for dealing with

personal inquiries.

The end of summer in Dawson meant an end to steamers, freights,

newcomers and Front Street activities. It meant the gnawing cold of

winter, digging, thawing and the endless confinement in smoky cabins.

There were, of course, diversions; unlike rural communities Dawson had

scores of saloons, dance-halls, theatres, restaurants and (ultimately)

ladies in Paradise Alley to compete for the gold of the lonely miner

during his first long winter inside. The store, however, continued to

hold its position as public assembly, reading room and social

club.68

Despite the general reputation of boom town populations, not every

Dawson citizen felt comfortable in the noise and smoky glitter of the

dancehall. With a few exceptions, Dawson's restaurants seem to have been

relatively cheerless eateries. The store, on the other hand, provided

some element of companionship. While the cracker barrel tradition was no

longer an element of its culture, the huge stove was undoubtedly the

centre of any store gathering. The daughter of one trader recalled a

vivid childhood memory of the tones of adult conversation punctuated by

the occasional sharp hiss of spit hitting the hot metal.69

This rag-chewing ran the usual gamut of Yukon topics from local

injustices to prospecting adventure (every sourdough had his own

"face-to-face-with-a-bear" story). References to the more distant past,

to one's outside ties, were scrupulously avoided.

When electricity came to Dawson, it came first to the stores. A

brightly lit room must have attracted many who found the hours of winter

darkness increasingly unbearable. One sourdough gives us an idea of just

how desperate the creek miner was for winter entertainment.

Dn the creek where I spent the first several years the only form

of recreation was playing cards by the light of a candle. There were

neither books nor magazines, and at times we were so wistful for a break

in the monotony that we would visit the store in the evenings and read

the labels on the cans.70

Lord Minto's Klondike diary records that in 1900 the stores and shops

seemed to be open night and day,71 a practice that was

probably directly related to long hours of summer daylight.

In time, some of the larger stores took to organizing activities to

help fill the winter months. Editions of the Dawson Daily News

during the winter of 1899-1900 made weekly references to hockey and

bowling tournaments set up between the employees of some of the larger

establishments. New Year's Day that year was celebrated around the punch

bowl in the AC Company's store.

There were still vestiges, indeed, of the kind of trust and

interdependence which had existed in the distant days along the Yukon

River. But it was obvious, in the next decade, that the simplicity of

this relationship would have to give way to the pressures of "progress

towards civilization and its influences." The closely knit "family" of

river traders working together more or less under the AC Company's

banner had been forced to take on a new and multifarious membership.

Streaming to the gold-bearing centres from all parts of the world, the

merchant group of 1898 and later brought a vast range of experiences and

backgrounds to bear on the traditional Yukon business methods. This new

group was no homogeneous whole in terms of specialities, ways of

operation or status in the community.

The next chapter focuses on one particular type of business and the

demands which helped to mould it. The grocery and provisions trade was

germane to all phases of Klondike outfitting and supply. As the Dawson

business community matured, the small-scale general store became a

peripheral rather than a central institution in the community. Only the

provision merchants remained to carry on the trade most reminiscent of

the gold-rush era in stores which were the most colourful emporia of

them all.

|