|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 26

Grubstake to Grocery Store: Supplying the Klondike, 1897-1907

by Margaret Archibald

The Great Outfitting Rush, 1897-98

When the soldiers from the east were drafted — or at least

When they volunteered to Klondike for to go,

They had to take their stuff, so that they would take enough,

In a most evaporated form you know.

So whether it was meat, or molasses for a treat,

Or whether it was whisky, eggs, or corn,

So that it would safely pack on a mule's uncertain back,

'Twas in the most compressed and concentrated form.

We'd evaporated flap-jacks, evaporated tin-tack,

Evaporated peaches and evaporated prunes,

Evaporated rice, beans, whisky, beer and ice-creams,

Evaporated flutes that played evaporated tunes....

We'd evaporated taters; O, they're the chest inflators!

Evaporated pork from an evaporated sow,

Evaporated eggs, crystallized and concentrated,

Even to the milk of an evaporated cow.

Private Green,

Royal Canadian Dragoons1

One tends to think of the impact of the Klondike

gold-rush in terms of a sudden discovery of the Yukon by the world at

large, and of the development of that territory at the hands of the

thousands who flowed north to the goldfields. Even realizing that over $100

million worth of gold was taken from those creeks in the first

10 years after the strike on Bonanza Creek, it is

difficult to calculate the impact of the widespread economic boom

triggered by the rush. Where did the money go?

This is to be a discussion of one segment of the

total bonanza; that is, of the share of the wealth which was staked from

the beginning by suppliers and outfitters across the continent,

specifically by those on the west coast. They went nowhere near the goldfields

nor, in all probability, did they want to. The combined factors of short

supplies and exorbitant prices necessitated the purchase of at least a

year's supplies before one entered that forbidding country. On this

basis, many a harbour wholesale dealer made his fortune.

Examination of the workings of this lucrative supply

trade serves to introduce the types of commodities which were initially

shipped or carried to Dawson. Once recognized, certain types of goods

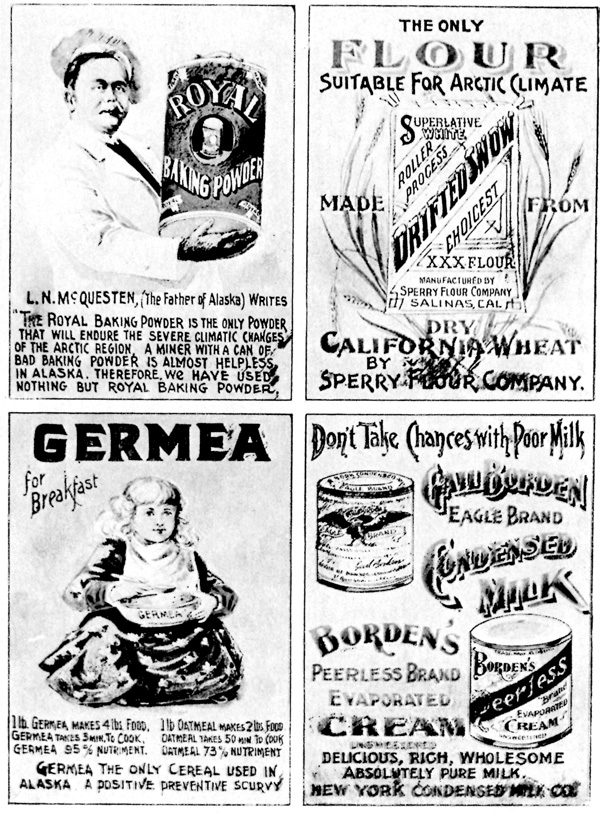

and specific brands can be traced through many years of

the Dawson retail trade. Some, like Borden's "Eagle

Brand" milk, were North American favourites even before the rush.

Others, like Lamont's crystallized eggs and Agen's tinned butter, while

not specifically developed for the north, were popular for their

suitability for such Yukon conditions as temperature extremes and extensive

periods in transit and storage.

A look at the geographical and economic structure of

the general outfitting trade brings to the fore those cities whose

locations and existing mechanisms for supplying the frontier served them

well in the business of outfitting the northbound hordes of gold

seekers. Of these cities Seattle is a fine example, especially since its

active Chamber of Commerce lost no time in mounting a highly effective

publicity campaign in order to promote its superior facilities. Nor did

it suffer from the prevailing misconception that the new goldfields were

in American territory. Here was one group whose optimistic belief in the

permanency of Klondike wealth proved accurate, for its members realized

that once secured, a profitable segment of the outfitting trade was the

thin edge of the wedge. By the 1890s distributors knew enough of the

techniques of marketing brand-name goods to realize that those brands

which established themselves early in a newly opened community could

lead to a market as permanent as the community itself.

The largest proportion of goods sold in the

outfitting centres was not, in the early stages of the rush, directly

intended for any Yukon merchant's shelves, although it seems probable

that large quantities of goods were purchased with resale in mind. No

matter what his or her intended activities at the goldfields might be,

every Klondike-bound fortune hunter would need an outfit — a year's

supply of everything that one person or party would need to survive. The

idea was hardly new to the North American frontier, for 19th-century

gold strikes in California, British Columbia and the Canadian northwest

as well as activities in logging, fur trading and exploring, had given

rise to equipped and knowledgeable groups of traders. It was their

business to outfit a man with due consideration to quality of goods,

durability in extreme climatic conditions, compactness and weight. All

this was based on the general estimate of 1,800 pounds of goods (or its

equivalent) per person per year.

To fulfill the most basic requirements of food and

shelter, an outfit consisted of provisions, dry goods, tools and gear

for transportation and shelter. Faced with a collection of outfit lists

from Seattle, Vancouver, Edmonton and Chicago, one is surprised by the

lack of regional variation in the staples offered. While there is

certainly no "regulation" outfit for the Klondike, it is possible to

ascertain more or less what the average goldseeker would have

carried north: about 1,000 pounds of food, soap,

candles and other groceries; basic cooking equipment; tools for boat- or

cabin-building; mining equipment; heavy clothing and boots, and a

sleeping bag.2

Of the many published guides which included outfit

lists, very few offered the tenderfoot Klondiker any sort of manual

which might give him proper advice on nutrition and on the efficient use

of this necessarily compact outfit. There were four which did: William

Ogilvie's excellent Klondike Official Guide, which was just that;

A.E. Ironmonger Sola's Klondike: Truth and Facts of the New El

Dorado, the Chicago Records book for goldseekers, and E.

Jerome Dyer's The Routes and Mineral Resources of North Western

Canada, published for the London Chamber of Mines. A second source

of instructive information, and of course a less reliable one, was the

advertisement which appeared in some guides, including Ogilvie's, the

Alaska Commercial Company's and Charles Lugrin's Yukon Gold

Fields, published by the Victoria Colonist.

The foodstuffs were unquestionably the most

important element of any outfit, though they were unfortunately the

bulkiest and heaviest as well. Although experienced firms packed outfits

in portable units not larger than 50 pounds (see Appendix L), the fact

remained that a single man could be expected to use up 500 pounds of

flour and other grains in a year. Other heavy items were the 150 pounds

of bacon, 100 pounds of beans and anywhere from 25 to 100 pounds of

sugar.3 The heaviest individual elements of the edibles were

the fruits and vegetables. By virtue of their weight and perishability,

they were frequently excluded from outfits, an omission which had

calamitous results. Scurvy was the traditional enemy of the badly

supplied miner in the north.

The food industry — packing, processing and

preserving — went through a period of experimentation which was

characteristic of the 19th century. One wonders if the throng of

outfitted goldseekers would have been a possibility had the Klondike's

resources been discovered a century earlier. Indeed the two processes

most relied on in providing a grocery outfit for the Klondike were new

to the 19th century. Foods were first successfully canned during the

Napoleonic Wars, and condensation received its impetus from the American

Civil War. By 1897 both methods had been taken over by efficient,

mass-producing industries.

The first patent for a "tin cannister" was registered

in England in 1810: "an iron can coated with tin and the cover soldered

on."4 Even then, spoilage was associated with the process,

because (it was believed) of the food's coming into contact with tainted

air; therefore early canning processes involved the cooking of food

already sealed in cans. By 1860, Louis Pasteur had

made known his theory of sealing tins hermetically.5 The

contents of any tin can of food were greeted with understandable

suspicion in Pasteur's day, for the process was still experimental,

crudely done and generally unreliable. It was another 30 years before

research was directly allied with the food industry. By that time, the

canning industry had sprung up, packing the harvest of market garden

and orchard alike into two- and three-pound tins. (The standard

Canadian two-pound tin can was 3-1/2 inches in diameter and 4-1/2 inches

high.)6 By 1905 there were almost 50 canneries in

Ontario.7

Meats and their preservation were also subject to

experimentation in search of improvements. Canning, as a method of

preserving small quantities of meat without the benefit of salt or cold

storage, was ideally suited to expeditions and long voyages. Captain Sir

Edward Parry carried canned meats and vegetables with him in the Arctic

in 1824.8

One of the major disadvantages associated with

packing tinned products on expeditions was their weight. Gail Borden,

an inquiring American schoolteacher and surveyor, became interested in

the dual problems of bulky and perishable foods. His experiments were

directed toward obtaining from a food its concentrated extract. One of

the first practical results of his work was his meat biscuit, a

concentrated mixture of wheat flour and beef. "Dry, inodorous, flat and

brittle,"9 the meat biscuit was perfectly suited to an

expeditionary outfit. Coinciding as it did with the California

gold-rush of 1849, Borden's discovery sold briskly. Basically his

biscuit was not unlike the traditional pemmican.

If Borden's name is even slightly connected with the

California gold-rush, then his subsequent discovery ought to have earned

his status as an honorary sourdough in the Klondike. For most of the men

at the goldfields or on the trail, Borden's "Eagle Brand" was synonymous

with condensed milk. This process, discovered by Borden in 1856,

condensed the milk by heating it in airtight vacuum pans.10

The liquid so produced was virtually imperishable. From the invention

evolved a company, producing Eagle Brand milk and "Peerless" evaporated

cream (see Fig. 1). Its foremost Canadian competitor, at least in terms

of the Klondike market, seems to have been the Truro Condensed Milk and

Canning Company (Figs. 2 and 3). "Reindeer" was their leading

brand:

The quantity of gold dust stored in Reindeer

Milk tins this season will be enormous. But it will not equal in

richness the original contents, for Reindeer Brand assays 1000

fine every time.11

1 Borden's best-known products, 1903.

(Canadian Grocer, Vol. 17, No. 45 [Nov. 1903], p. 11)

|

2 Condensed milk, 1904.

(Canadian Grocer, Vol. 18 [Dec. 1904], p. 5)

|

3 "Reindeer" trademark, 1919.

(Department of Consumer and Coporate Affairs, Trade Marks Registry.)

|

Other dairy products underwent similar adaptation for

use on expeditions. Vacuum-packed tinned butter never lost the early

popularity it had gained in Dawson. Packed so that it did not touch the

tin (presumably by using paper liners) this butter was reputed to

withstand the most extreme climatic conditions. J.B. Agens of Seattle

and Tacoma held a long-lasting monopoly in canned butter at the

goldfields (Fig. 4).

4 Agen's butter label, pack of 1903.

|

Whole eggs were useless in an outfit for obvious

reasons. To this problem the crystallized or powdered egg was the

answer. Lamont's crystallized eggs captured the Dawson market by

advertising, "No breaking. No Bad Eggs. No shells. No waste."12

Lamont had reduced the equivalent of two dozen eggs to an eight-ounce

can; to reconstitute one whole egg one needed only to add 1-1/4

tablespoons of baking powder and 2 tablespoons water or milk.

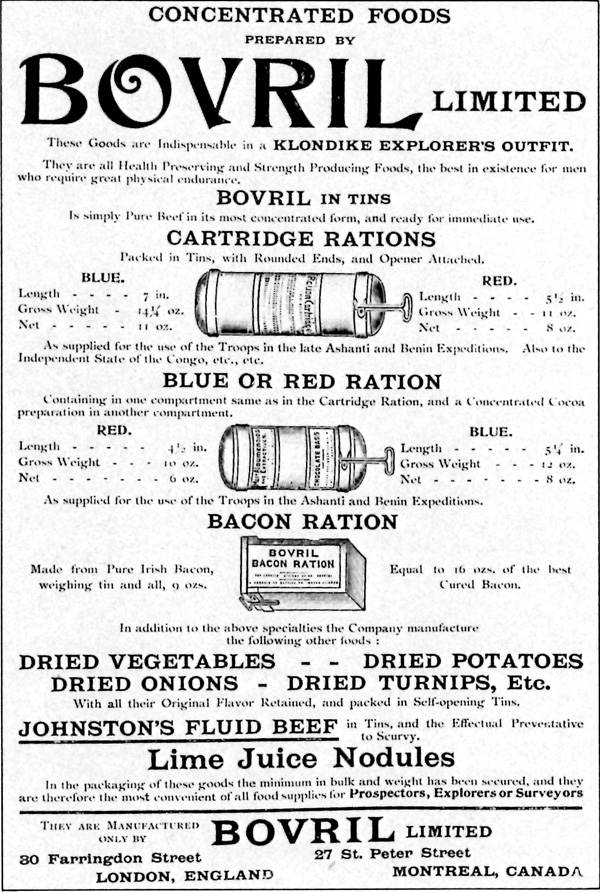

The process of concentration was not limited to dairy

products. Meat, fruit and vegetables could be reduced to a fraction of

their original weight, thereby both lightening the load and preserving

the food. Bovril was by far the best-known company engaged in reducing

meats and, to a lesser extent, vegetables. "Our object is to supply the

maximum amount of nourishment in the minimum of bulk."13 With

vast experience behind it, having outfitted prospectors, explorers,

surveyors and troops in the far reaches of the empire, the company was

up to this latest challenge. Numerous combinations of beef, bacon,

cocoa and vegetables in various reduced "cartridge" rations were

available (Fig. 5).

5 Bovril's cartridge rations, 1898.

(William Oglive, Klondike

Official Guid. Canada's Great Gold Fields, the Yukon . . . with

Regulations Governing Placer Mining [Toronto: Hunter, Rose, 1898], p.

xvi.)

|

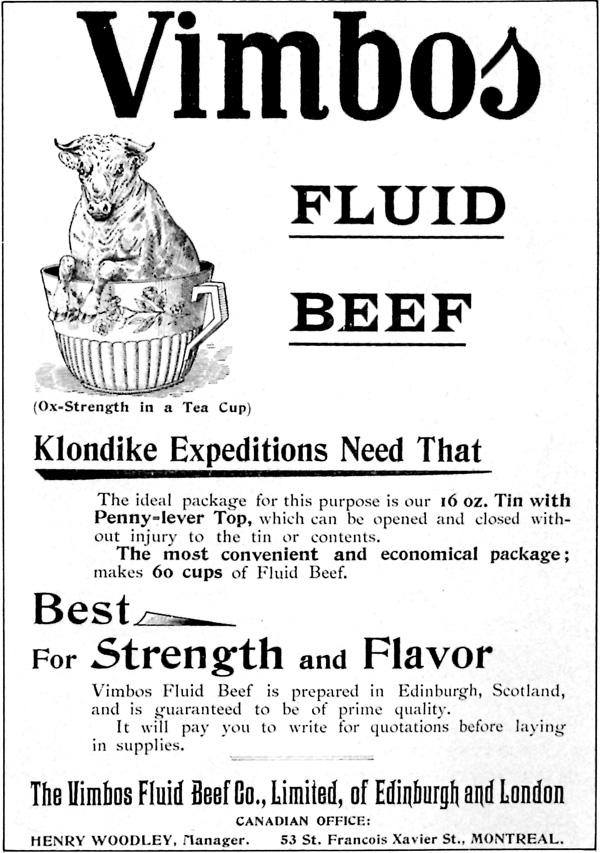

Along with "Maggi" and "Vimbo's Fluid Beef," Bovril

won itself a permanent niche, not just in the well-packed outfit but

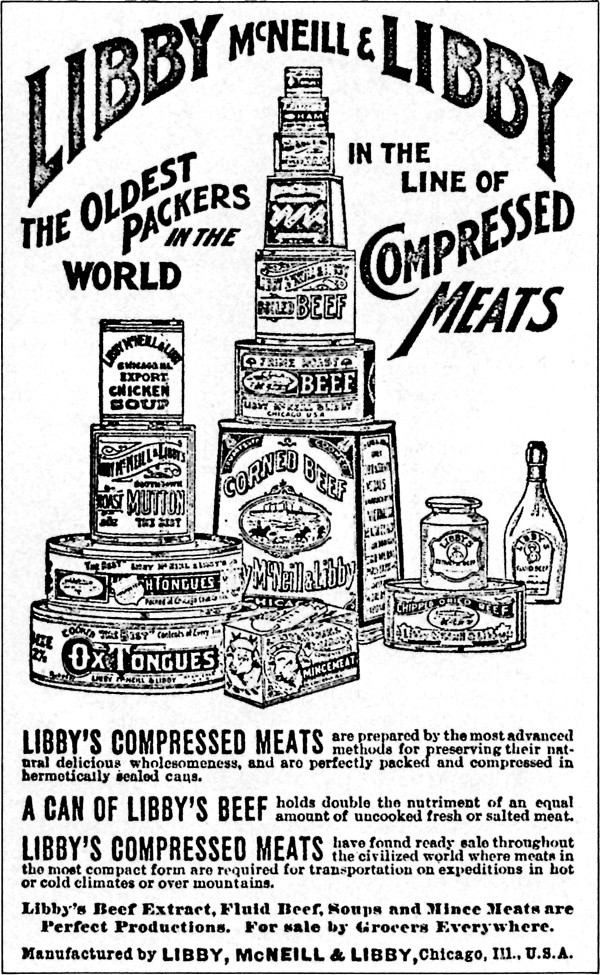

behind the counters of Dawson as well (Fig. 6). Libby, McNeill and Libby

of Chicago were prolific canners of beef in all its forms, as well as of

roast mutton, ham, tongue and soup (Figs. 7, 8). For the Klondike,

however, beef extracts had the advantage over canned products. William

Ogilvie, with the authority of a veteran surveyor in the territory,

personally advised against taking meats in tinned form.14

6 Vimbo's fluid beef, as advertised for the Klondike, 1898.

(William Oglive, Klondike Official Guid.

Canada's Great Gold Fields, the Yukon . . . with Regulations Governing

Placer Mining [Toronto: Hunter, Rose, 1898], p. x.)

|

7 Libby Mcneil and Libby compressed meats, 1898.

(Source Unknown)

|

8 Corned Beef, advertised by the Alaska Commercial Company, 1898.

(Alaska Commercial Company, To the Klondike Gold Fields, and Other

Points of Interest in Alaska [San Francisco: 1898], n.p.

|

Evaporated, or simply dried, fruits and vegetables

were perfectly suited to the Klondike situation. No outfit was complete

without about 100 pounds of fruits and vegetables in this form.

Advertisements of the period lead one to believe that there was not a

fruit known to man which was not evaporated and packed for sale to the

Klondike-bound. Potatoes, sliced and dried, were especially popular.

"Lubeck" was a brand of dried potatoes which sold consistently in

Dawson, but it is not known whether it was produced initially for the

outfit trade or not.

From the point of view of a world accustomed to

frozen foods and chemical additives, the number of processes in use at

the end of the century to reduce and preserve foods — all in the

name of lightness and durability — is surprising. The prospector's

diet was not simply canned; it was evaporated, concentrated, dessicated,

compressed, liquified, crystallized and granulated. His beef and sugar

(not to mention his lemons, limes, celery and milk) might come in

tablets; his coffee and tea in lozenges, his cocoa in cakes. One

extremist managed to put together an outfit made up exclusively of such

drastically reduced foods as these which, when complete, weighed a mere

69-1/2 pounds.15 In describing this quintessence of

gastronomic delight, the author of the publication reported with a

remarkable evenness of tone: "Almost everything comes in a powder or a

paste, and needs nothing but boiling water and an appetite to make a

meal."16 It is easy to imagine the monotony of food in the

cabins and on the trail. No doubt the least concentrated and most

appetizing goods were consumed first. For the last months in the season,

the remaining evaporated delicacies must have exhibited a dreary

sameness.

Whether the contents were whole, canned or dried, the

trend toward the use of brand-name food products was a significant one.

In an age of abundance and expansion in the food processing and packing

industry, adulteration had become an established practice. Since there

was still little effective legislation enforcing inspection and other

controls in either the United States or Canada,17 those

brands which guaranteed the purity of their products in their

advertising gained respectability in the market. The AC Company, in its

promotional Klondike pamphlet, included testimonials from no less an

authority than Jack McQuesten for brands considered trustworthy over the

years. His support of Eagle Brand milk is indicative of the general

trust put in known varieties.

There is nothing more precious, perhaps, to a

miner in the Arctic than a can of good condensed milk or cream. This is

so well known in Alaska that the Miners there will buy nothing but the

"Eagle" brand, but it is the ignorant miner — and only the ignorant

miner — that is fitting out in San Francisco or Seattle who ever

allows any other brand to be foisted on him, and he will find out when

he reaches Alaska, where the temperature is 80° below zero

sometimes, that his cheap, inferior milk is no good.

18

A similar endorsement was given to "Royal" baking

powder, the only kind (according to the AC Company) which would with

stand climatic conditions "harsher against baking powder than against

anything else." Other brands singled out for commendation were "Germea"

breakfast cereal (highly concentrated and nutritive, quick-cooking and a

preventative of scurvy), Sperry's "Drifted Snow" flour (for its dryness)

and Baker's cocoa and chocolate (withstanding extreme conditions, and

also preventing scurvy) (Fig. 9).

9 Endorsements by Jack McQuesten, 1898,

(Alaska Commercial Company, To the Klondike

Gold Fields and Other Points of Interest in Alaska [San Francisco,

1898], n.p.)

|

William Ogilvie was an experienced and more impartial

adviser. Less concerned with specific brands, he offered such general

sound advice as the fact that good fatty bacon, oatmeal and good black

tea ("the cup that cheers but not inebriates") should all be included in

an outfit for their warming qualities. Good medium flour and ordinary

brown beans were the most sensible investments in their kinds. Good

quality granulated sugar was preferable to brown, which was more apt to

freeze in winter.19

Unfortunately, the health of the miner was not the

concern to outfitters that it might have been. While some guides

included advertisements by wholesale druggists, only about a quarter of

the lists collected for this report included a medicine kit —

usually a $4 or $5 package. One advertisement for a "health regulator"

struck at the grim but realistic truth that miners and suppliers, in

their mutual haste to strike gold, ignored "Don't kill the goose that

lays the golden egg. Your future wealth depends upon your present

health. Take care of it in your own interests."20 One

reporter for the Chicago Record, who had already made the

overland trip, bemoaned the fact that so very little importance was

attached to the medical chest. He suggested the following useful items:

liniment for sprains and cold on the lungs, tincture of iron to

enrich the blood, extract of Jamaica ginger, laudanum, vaseline,

carbolic ointment, salts, cough tablets, mustard and adhesive plaster,

surgeon's lint, bandages, liver pills, powder for bleeding, absorbent

cotton, surgeon's sponge, needles and silk, quinine capsules and

toothache drops.21

While scurvy from a poor, unvaried diet was indeed a

grim possibility, those miners who listened to any expert advice were

clearly aware of the dangers and packed preventatives accordingly. One

encouraging feature of this gruesome disease was its amenability to

treatment in all but its most advanced stages.22 The

well-known role of ascorbic acid in its prevention and cure was

acknowledged in many outfits by the inclusion of lime juice or tablets

of citrus fruit extract containing the acid. "Montserrat Lime Fruit

Juice" and L. Rose and Company's lime juice were both reputable

products. While most of the goldseekers were probably unaware of the

fact, canned tomatoes also contained the necessary vitamin

C.23

An additional worry for the miner was that not every

company which put up medicine boxes with their supplies could be trusted

to fulfill the task knowledgeably or honestly. Her discovery that

certain drugs were missing from her medicine chest drove one

Klondike-bound traveller to write angrily that "merchants seem to

think that when they outfit you for the Klondike thay

can put upon you all the stuff that no one else will take and that they

will never hear from you again."24 Given the suddenness of

the Klondike phenomenon, the customers' general eagerness and their

ignorance, both of their needs and of their suppliers, dishonesty must have

been fairly common among the less scrupulous merchants in the trade. The

number of reported grievances, even in private papers, is surprisingly

low.

The food discussed above made up the basic provisions

outfit taken by the wise miner. There were those, of course, whose

tastes ran to such portable treats as cake and cookies, pickles, spices,

cheese and jellies. Like the treasured tobacco supply, these delicacies

were probably consumed before Dawson came into view.25 Such

luxuries did have an additional value; they could be used for purposes

of barter along the trail. While the intelligent traveller knew that it

was sheer folly to weight one's pack more than was absolutely necessary

with these extra pots and jars, one with a certain enterprising spirit

looked at the situation in a different light. He was almost sure to meet

some fellow gold-seeker, desperate in his deprivation, who was willing

to pay almost anything for a plug of "Old Chum" or a tin of "Log Cabin"

maple syrup.

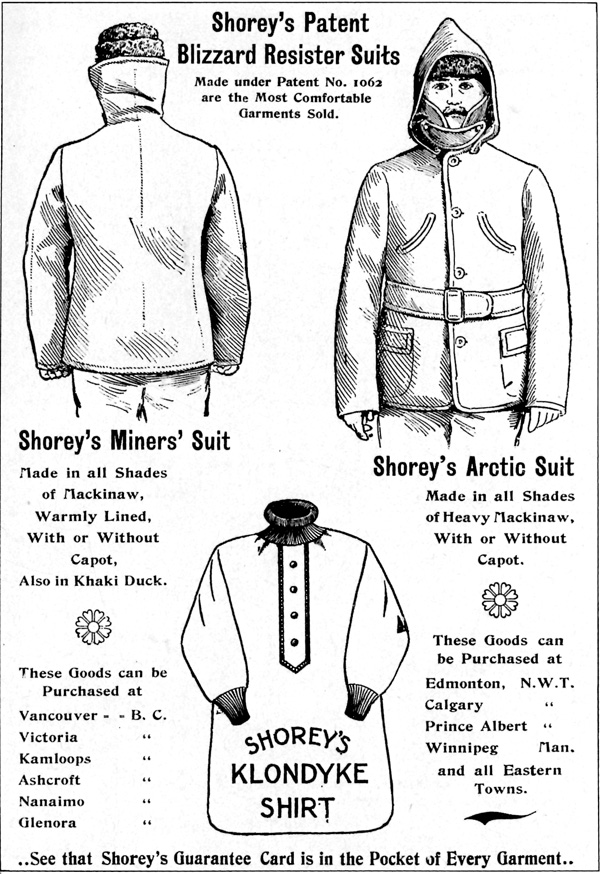

In the line of clothing, one comes across general

types of garments offered by most outfitters rather than specific brand

names. The most important items were heavy lined suits of mackinaw (a

blanket-like wool, either grey or plaid), wool, tweed, serge, corduroy,

khaki or waterproofed cotton duck. Under this went heavy sweaters,

woollen socks and knit underwear. The most descriptive selection of

Klondike clothing was offered by the T. Eaton Company in a special

Klondike section of their fall and winter catalogue for 1898 (see Fig.

10). Items "B" and "C" are Shorey's "Patented Blizzard Resister Suits"

and item "G" is the Klondike shirt made by the same company (Fig. 11).

These articles were still being distributed through Eaton's long after

the gold-rush had subsided.

10 Klondike clothing featured by the T. Eaton Company, Spring and

Summer Catalogue (No. 40) 1898.

(The Archives, Eaton's of Canada

Limited, The T. Eaton Company Limited Catalogue, 1898, p 124.)

|

11 Shorey's famous shirts and suitss.

(William Ogilvie, Klondike Official Guide,

Canada's Great Gold Fields, The Yukon . . . with Regulations Governing

Placer Mining [Toronto: Hunter, Rose, 1898], p. xxvii.)

|

Several companies offered everything from robes to

parkas, pants, hats and mittens in fur. Few goldseekers, however, could

afford fur robes and, because of the greater freedom of movement

afforded by fabric clothing, the native skins (as they were called in

the Yukon) were more attractive to those not actively engaged in

mining.26 Instead of fur robes, most buyers would be

satisfied with several heavy blankets, available for less than $10,

along with an oilcloth cover. The sleeping bag was gaining popularity,

as the Eaton's catalogue shows. Usually of oiled, rubbered or plain

cotton, it was lined with eiderdown, fur, wool or felt and cost between

$10 and $20 (Fig. 12).

12 Advertising by association in the Ogilvie guide.

(William Ogilvie, Klondike Official Guide,

Canada's Great Gold Fields, The Yukon . . . with Regulations Governing

Placer Mining [Toronto: Hunter, Rose, 1898], p. xxxviii.)

|

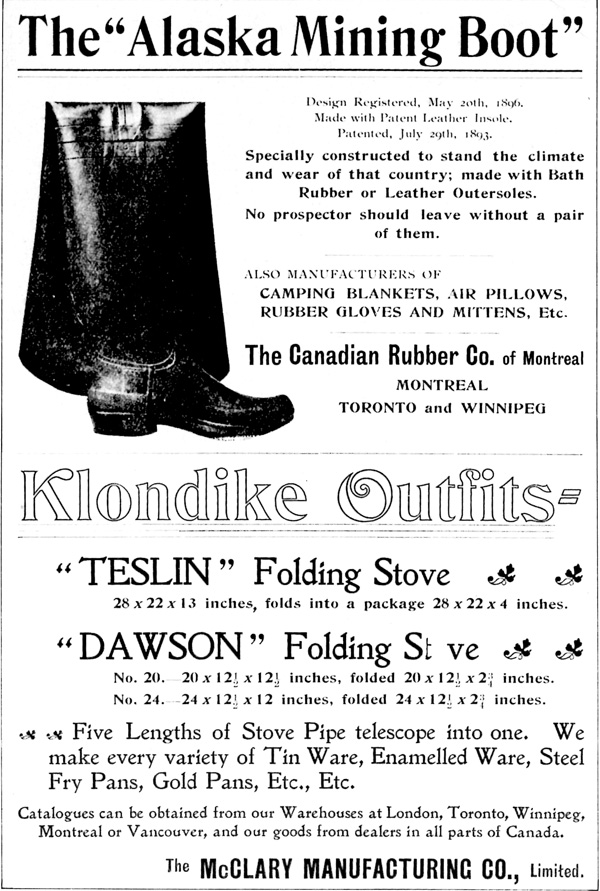

As for boots, the miner would have to be outfitted

with two distinct types. Winter definitely called for "native boots" or

mukluks, which could be purchased in the north.27 For the

spring mud along the creeks, rubber boots were essential. Several pairs

of snag-proof, unlined hip-waders were advisable. This was one area of

the clothing outfit where brand names did emerge. The AC Company stood

behind the patented snag-proof and crack-proof "Gold Seal" products of

the Goodyear Rubber Company of San Francisco. In Vancouver, "English

K-boots" ("guaranteed absolutely waterproof, snagproof gum boots") were

advertised,28 while the Canadian Rubber Company of Montreal

offered the "Alaska Mining Boot" (Fig. 13). Waterproof rawhide boots

were popular; they were more suitable for the arduous trails than for

the final muddy destination. George T. Slater and Sons of Montreal

produced a boot for $8 that remained a well-known brand in Dawson (Fig.

14).

13 The Alaska Mining Boot, from the Canadian Rubber Company (Montreal,

Toronto, and Winnipeg), 1898.

(William Ogilvie, Klondike Official Guide,

Canada's Great Gold Fields, The Yukon . . . with Regulations Governing

Placer Mining [Toronto: Hunter, Rose, 1898], p. xliv.)

|

14 The Slater mining boot, 1898 — consistently popular in outfits

and (later) in Dawson.

(William Ogilvie, Klondike Official Guide,

Canada's Great Gold Fields, The Yukon . . . with Regulations Governing

Placer Mining [Toronto: Hunter, Rose, 1898], p. xxxvii.)

|

Completing the clothing outfit were heavy wool socks,

called arctic socks or often "German wool socks," underclothing (Jaeger

flannel was common), mosquito netting and snow goggles. Depending on the

season in which one started north, one of the last two items would be

essential to one's travelling comfort. Again, the brand names made

popular by the strike remained so in Dawson stores.

The hardware list in the outfits sold by McDougall

and Secord was much like the one recommended by Ogilvie

himself.29 In addition to the tools and utensils which must

have been familiar to all woodsmen and explorers, certain items were

particularly adapted to the life and survival of the Klondike miner. The

gold pan and scales were obvious inclusions, as were pick and shovel.

In the hands of a resourceful miner, the pan could be used both as wash

basin and bread pan.

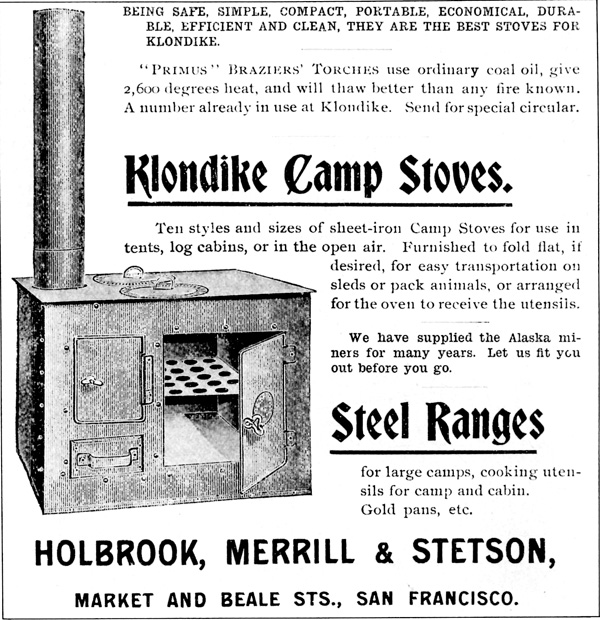

A more significant addition was the collapsible camp

stove. Often called the Yukon stove or Klondike camp stove, this article

was considered to be a unique northern adaptation. Its origin was

claimed by the city of Seattle.30 Its worth can be attributed

to its collapsibility. The sides of the box-like stove folded, and the

pipe telescoped into four or five pieces (Fig. 15). It could be carried

easily, although it was, after all, made of sheet-iron. (One model was

advertised as weighing a mere 17 pounds.)31 It was a compact

piece of work, about 9 inches by 12 inches by 24 inches, and its design

was such that "even on the coldest days it could keep a properly chinked

and roofed cabin uncomfortably warm."32 Often the tank of the

stove was divided between fire box and oven. While the box-shaped model

might have from two to five lids, there was a half-barrel and a

cylindrical shape as well which served only as heater and oven. Since it

was both absolutely necessary as well as relatively simple to construct,

this article was soon manufactured right in Dawson.33

15 One version of the collapsible Yukon stove.

(Alaska Commercial Company, To the Klondike

Gold Fields, and Other Points of Interest in Alaska [San Francisco:

1898], n.p.)

|

Another peculiarity of the Klondike outfit, intended

for those miners crossing the passes, was the inclusion of tools and

materials (other than lumber) necessary to build a craft to descend from

the head of Bennett Lake to Dawson City. These included a whipsaw,

crosscut saw, pitch, oakum, caulking iron, hammer and nails, jack plane,

chisel, brace and bits, knife and rope. For those who wished to avoid

the delay of having to build a boat, portable sectional canoes were

sold.34

The problems encountered by the miner who discovered

too late that his outfit contained useless quantities of goods have

already been mentioned. In the case of an excess of hardware or food,

the packs were either jettisoned or traded off, depending on the

relative demand for the product.35 In this way booths stocked

with the leavings of disheartened goldseekers became a familiar feature

along the Trail of '98. For those who ran them, this was often the first

step to a lifetime's work of merchandizing in the north.

The sudden demand for nearly a ton of supplies for

each of tens of thousands of adventurers was an unexpected shot in the

arm for the food supply industry across the continent. The news of the

Klondike gold finds which had arrived in July of 1897 with the first

nugget-laden ships, Excelsior and Portland, must have

excited astute wholesale dealers along the steamship routes. It opened

the possibility not only of profiting from the outfitting trade, but of

eventually earning a share of the market at the gold fields for as long

as the capricious paystreak would support one.

Of the west coast cities in competition for the

outfitting trade — San Francisco, Seattle, Portland, Tacoma,

Victoria and Vancouver — all had some experience in the business.

San Francisco, of course, had the edge on the rest of them, being the

supply depot and port for the pioneer AC Company. During the previous 20

years, however, Seattle had begun to catch up; her productive hinterland

had been greatly expanded by the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railway

at her back doorstep in 1885.36 By the early 1890s she had

gained a secure monopoly of the trade to Juneau, the commercial centre

for the hard-rock gold mining operations conducted on the Alaskan

panhandle since 1880,37 and in 1897 had been an outfitting

base for some of the first Klondikers over the passes.38 The

feather in Seattle's cap, and an event which launched her into serious

competition with San Francisco, was the decision of the newly formed

NAT&T Company to use Seattle as its Pacific coast

entrepôt.39

The Canadian ports of Victoria and Vancouver had both

earned admirable reputations as wholesale supply and outfitting centres.

With 50 years of experience under their belts in servicing the Cariboo,

Cassiar and Kootenay gold-rushes, they were recommended by William

Ogilvie in his Klondike Official Guide for the outstanding

usefulness of their goods.40

Also experienced, but in a less favourable location,

were the northwest centres of Edmonton, Calgary and Prince Albert.

Undaunted, these towns publicized the overland route (via the Mackenzie

watershed).41 While Edmonton merchants did indeed manage to

profit from the gold-rush,42 they could hardly continue

shipping goods along the impossible and tortuous wilderness route which

they had once urged the goldseekers to follow.

The spoils, in terms of continuing trade with the

Yukon, were divided, therefore, among those cities on the Pacific water

routes. It was to Seattle that the greatest number of Klondikers

thronged. This was the hard-earned fruit of a publicity campaign run by

the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, whereby advertising was carried on

through mayors, postmasters, public libraries, railways and newspapers

across the nation.43 In terms of an intense, immediate and

far-reaching reaction to the news of gold, no city was able to match it.

By the time other cities tried to adopt Seattle's methods, that city's

initial monopoly had been established.44 The first year's

reward for Seattle merchants was an estimated $10

million.45

During the previous decade of commercial success,

several Seattle firms had begun to flourish in the general grocery and

wholesale hardware line. The well-known wholesalers included the

Schwabacher Brothers, Seattle Trading Company, Harrington and Smith

(bought out by A.E. MacCulsky in 1893) and Fischer

Brothers.46 As for the food processing industry, the farming

country around the city produced quantities of raw materials for the

much-needed staples — condensed milk, evaporated or dried fruits

and vegetables and food extracts. A look at various lists of outfits

shows that, while Canadian firms were competitive on some counts (flour,

bacon and some fresh produce, for example), for the most part Seattle

could pack provisions more cheaply. To market these products in the form

of outfits, a new type of wholesale firm emerged that dealt mainly in

groceries.47 The dealers, supported by the Klondike trade,

could handle the large demands in provisions and could outfit

prospecting parties. Individual consumers had to buy from large

retailers who could handle the range of single orders for the Klondike.

An example of such a foods broker was the firm of Frank and May, which

in 1895 advertised as manufacturers' agents. Various small industries

had recently grown between railhead and port. In combination with the

existing lumbering industry, these had also converted Seattle into a

strong hardware-producing centre.48

One significant feature of Seattle's successful

outfitting business was the organizaton that pervaded the trade early in

the game. The descriptive article which follows appeared in the Toronto

Globe in February 1898.

[The Seattle merchants] began to see not lists of

goods in various lines but outfits. They prepared and packed complete

outfits containing every thing necessary for the trip and a year's

sojourning in the arctic placers. Intending Klondikers were not obliged

to inquire of experts regarding their future needs and to hunt about

among a number of stores to obtain supplies. They could find their

hardware, groceries, furs, clothing, tools, cooking utensils, etc. all

ready packed and ticketed as to weight and price at the outfitter's

store. An outfit for one, two, three or four persons could be obtained

without delay and without the risk of overlooking anything essential.

This trade was fully established in Seattle while the British Columbia

merchants were still adhering to their own lines of supplies and causing

their customers to go from store to store when buying

outfits.49

Seattle's other advantage lay in the official realm

of customs regulations. As long as there were no Canadian customs

officers at the summits of the passes (that is, at the international

border) Americans could bring in their supplies duty-free, avoiding the

tariff that, for the commodities in question, ran between 25 and 30 per

cent on the average. Although this loophole was plugged by the Canadian

government by August 1897,50 Seattle's "duty-free" reputation

had been established. Ironically, it was still the Canadian-based

Klondiker who suffered at the border. Until May 1898, American bonding

regulations on Canadian goods were so severe and convoying fees across

the panhandle so high that it was simpler to pay American duties at

Dyea.51

As in Seattle, it was the wholesale dealer in

Canadian centres who was most prepared to outfit. As the Globe

article quoted above indicates, however, trade in Victoria and Vancouver

was handled to a larger degree by specialists. In Vancouver, for

instance, there were over twice as many wholesale grocers as either

hardware or dry goods firms advertising in the "Holiday Klondike

Edition." Lugrin's Yukon Gold Fields shows a preponderance of

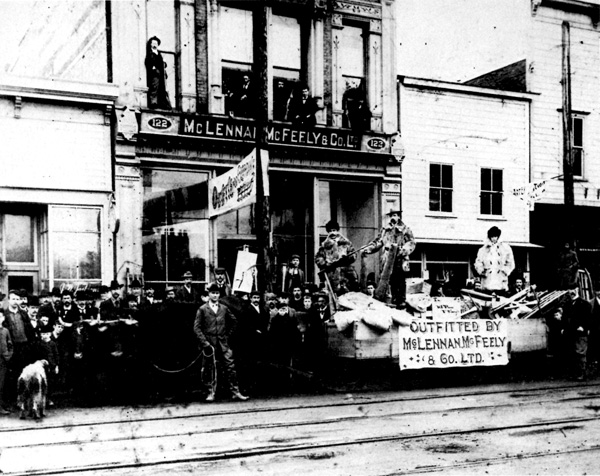

clothing merchants in Victoria. In tools and hardware, the name

McLennan, McFeely and Company is irrevocably attached to any reference

to Vancouver's role in the gold-rush.

It appeared at first that Seattle's main source of

competition would come from the active British Columbia port of

Victoria. Indeed, the Victoria Daily Colonist's first Klondike

outfitting advertisement for miner's clothing outfits from Marks'

appeared on 20 July 1897, only a few days after the news brought by the

Excelsior and Portland had burst on the world. Victoria's

campaign gained momentum throughout that first month and rose to an

early peak with the publication of the pamphlet Yukon Gold Fields

by Charles Lugrin, the Colonist's editor. Heavily supported by

local merchant advertising, the publication sold well in eastern Canada,

where the Victoria Board of Trade intended to focus its advertising

resources.52

Bypassed by Klondike-bound steamers from both Seattle

and Victoria,53 Vancouver had a poor position in the opening

lineup. Not until the new year, when two CPR steamers were transferred

to the Vancouver-Skagway run, were Vancouver's inadequate shipping

facilities increased to the point where it could compete as a point of

departure.54 Consequently, the reaction of Vancouver's

business sector to the rush past its door was a belated one. Sporadic

Klondike advertising in the Vancouver Daily World was not

replaced by impressive and consistent daily copy until after the

"Holiday Klondike Edition" came out on 31 December 1897. Once fully

mobilized, however, the Vancouver outfitting trade reached its peak

between February and June 1898.

The notable exception to specialized outfitting on

the Canadian west coast was the Hudson's Bay Company, the most seasoned

provider of them all. While the company's advertising was kept to a

low-keyed minimum, they announced in the spring of 1898 that they were

unable to keep abreast of orders.55 One can easily appreciate

the pace of their business in Vancouver in March 1898:

It is like a trip from Paris to Siberia to take

the elevator from the fashionable lower floors of their block to the

uppermost storey where piles of every conceivable supply for an arctic

zone from dessicated potatoes to moosehide moccasins are scattered

around while the busy clerks sell, pack and shift the goods away.

56

Another account of outfitting in that city, in

February 1898, maintains that, in those grocery and hardware stores

doing the most roaring business, shelves were completely empty by

nightfall. This report singles out druggists as a third group to profit

greatly from the rush, "furnishing men and women with different

medications to fight scurvy, and especially unguents to discourage black

flies and mosquitoes."57

The initial outfitting rush was short-lived; it

lasted only until the end of the 1898 season.58 By the fall

of that year, Vancouver and Victoria merchants alike were plagued by

overstocked shelves.59 The battle between Seattle and

Vancouver continued, but from then on it was to be fought over the

long-term privilege of supplying Dawson retailers. While Victoria had

originally seemed the most likely rival to the American port, her

position was in fact taken over by Vancouver. Once the two cities'

shipping was equalized, Vancouver's rail connections with the east

earned her a more advantageous position from which to deal with incoming

goods and goldseekers.

One very significant outcome of the outfitting rush

was the keen and continuing interest in the Yukon trade which was

generated by the outfitting experience of several Vancouver merchants.

The Oppenheimer Brothers, commission merchants, importers and wholesale

dealers in groceries, provisions, cigars, tobaccos and so forth, were

leading participants in the Vancouver Board of Trade's campaign to wrest

the Yukon trade monopoly from Seattle.60 McLennan, McFeely

and Company lost no time in establishing one of the earliest hardware

and tinsmithing businesses in Dawson61 (Figs. 16 and 17).

McLennan himself moved north to manage the outlet, becoming Dawson's

mayor in 1903. Thomas Dunn and Company, another wholesale hardware firm,

made a long-lasting contact as one of the largest single suppliers of

the Dawson Hardware Company. Kelly Douglas (in wholesale grocery

supplies) remains to this day as familiar a name in the Yukon merchant's

vocabulary as "Mc & Mc."

16 McLennan, McFeely and Company; outfitting for the Klondike from

New Westminster, B.C.

(Centennial Museum, Vancouver)

|

17 The first Dawson headquarters of "Mc & Mc"s hardware store

and tinshop, ca. 1898.

(Public Archives Canada, PA 13497.)

|

Calgary, Edmonton and Prince Albert were all

recognized as experienced outfitting centres,62 and enjoyed

in addition the reputation of being the gates to the only all-Canadian

route to the Klondike. Despite the rigours of the long overland haul

along the Athabasca and Mackenzie rivers, it was a much-promoted route.

Not the least enthusiastic of its promoters were the Toronto and

Montreal suppliers who stood to profit directly from extensive

outfitting in the northwest.63 To the disappointment of all

business interests concerned, the all-Canadian route never became a

major shipping route to the Yukon.

While the outfits offered in these centres were

complete in all areas, the prices were higher than on the coast (with

the exception of those for flour and bacon).64 Along with the

Hudson's Bay Company, which had branches in Winnipeg, Calgary and

Edmonton, the firms of McDougall and Secord and of Larue and Picard

offered complete outfitting services in Edmonton. In Prince Albert, the

majority of establishments were the experienced type of "general

merchants and Indian traders...in the north for 15 years" who could

outfit a man with everything from picks to packaged

potatoes.65

While at first glance it seems that the spoils of the

Klondike rush went to Pacific coast merchants, Montreal and Toronto

enjoyed a steady growth in the areas of importing, processing,

manufacturing and distribution which permanently expanded their

lucrative western market. It is worth noting at this point that the

Toronto Board of Trade believed itself to have been influential in

securing bonding privileges in Alaska more suitable to the entry of

greater volumes of Canadian products.66 While the names of

Seattle and Vancouver distributors became bywords to the thousands of

Klondikers they supplied, eastern manufacturers immediately understood

the potential profit in establishing their brands in the north through

these agents.

Outfitting was not a recent tradition in eastern

centres. Estimates of the extent of individual outfitting in Montreal

and Toronto as opposed to other cities are based on sketchy information.

While there are few personal accounts which relate experiences of

eastern outfitting, advertising in the Globe was considerable,

and articles early in the 1898 season made much of Toronto's advantages

as a starting point for the Klondike. One could outfit as early as

possible, prices were lower, superior goods were assured and through

freight rates were available.67 Montreal in that period is

reported to have had the exclusive privilege of outfitting British

goldseekers entering Canada at that port.68

It was the newly stimulated food processing industry

that was to earn outfitting prominence for these cities. The sudden

flourishing of advertisements for suppliers and their jobbers, geared

toward the Klondike outfitter, was a salient feature of the Canadian

Grocer trade magazine early in 1898. One of its first issues that

year states that "quantities of evaporated vegetables, carrots, onions

etc., are being put upon the market in concentrated and convenient form

for the Klondyke trade."69 The Tillson Company of

Tillsonburg, Ontario (split peas, kiln-dried), the Acme Dried Vegetable

Company and the Kerr Vegetable Evaporating Company all focused their

energies on supplying the Klondike through grocery jobbers and

agents.70

The canning industry was another to benefit from the

suddenly increased west coast demand. W. Boulter and Sons of Picton,

Ontario, shipped two CPR carloads of "Lion" brand canned corn to

Vancouver and San Francisco. By June of 1898, 3,500 cases of the

upcoming pack of tomatoes and corn were reported ready to

follow.71 While rumours of spectacular deals between eastern

firms and Yukon trading companies continued to fly,72 actual

market reports of unusually brisk trade in wholesale canned goods gave

backing to the optimistic speculation.73

Importers, especially those in Montreal, gained the

agency for several Klondike-bound British products. Bovril, Vimbo's

Fluid Beef and E. Lozenby and Son's soup squares were all British

products sold through such Montreal dealers as A.P. Tippet and Company

of Montreal and Toronto.74 One unnamed German manufacturer

was allegedly doing well on the west coast and among eastern

wholesalers, selling a product which had known 15 years of consistently

slack markets.75 Demand for his line of assorted evaporated

vegetables reached dizzying proportions, thanks to the Klondike.

The commercial link between Ontario food packers and

British Columbia outfitters was firmly maintained throughout the

gold-rush and beyond by a relatively small and secure group of food

wholesalers that jobbed (that is, distributed) the manufacturers' goods

among western retailers. W.H. Seyler and Company, Eby, Blain and

Company, Warren Brothers, and Davidson and Hays, all of Toronto,

furthered their reputations as reliable distributors and thereby

profited greatly, albeit indirectly, from the great discovery of

1896.

As the rush of individual goldseekers over the passes

was a phenomenon of the winter and spring of 1898, the frenetic attempt

to provide necessities to these men faded when their goal was reached.

During the summer of 1898, once the mass of goldseekers had reached

Dawson, a new supply system took over. The simplest statement that one

can make about the fascinating mercantile mosaic of that summer is that

trade was largely a matter of reselling the tens of thousands of tons of

goods which arrived at the waterfront. This activity resulted in acute

shortages in certain areas, exorbitant prices and uncertain quality of

goods. These elements of unpredictability made for a chaotic, if

picturesque, throng of companies, storekeepers, jobbers, pedlars and

simple dealers.

As the shipping season closed, after the

faint-hearted had sold out their outfits and gone home, it became clear

that "starvation" winters, at least, were a thing of the past. Since few

would venture into the Yukon valley before the next spring, the

outfitting trade suffered a predictable slump. As such, the end of the

1898 shipping season marks a point of transition. For many outfitters,

contact with the wealth of the Klondike would be limited to the early

enthusiasms of 1897-98. For the larger, more experienced and more

persistent companies, the initial rush would turn out to be more than a

flash in the pan. Klondike gold was indeed going to hold out, and since

their foundations had been successfully laid in the previous year or

before, these companies would be the ones to reap the benefits of the

new trade patterns by becoming steady wholesale suppliers to the Dawson

merchants. To extend their bonanza, they had only to come to grips with

the combined problems of distance, terrain and climate in order to

supply the motley Dawson market with whatever it wanted — for as

long as gold held out.

|

|

|

|