|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 26

Grubstake to Grocery Store: Supplying the Klondike, 1897-1907

by Margaret Archibald

Swamp to Boom Town: Dawson from 1896 to 1898

It was not by accident that Dawson's founder and

first resident was an entrepreneur and speculator and that within a

month of the Klondike strike he had set up a general store and sawmill

to supply the imminent throng of goldseekers. After 13 years as a Yukon

River trader, Joseph Ladue realized that the most reliable way to profit

from a placer camp was to provide it with the essential services of food

and shelter. He had spent his Yukon days doing just that, first under

the banner of the AC Company and later in an independent partnership

with the veteran trader Arthur Harper at Sixty Mile (or Ogilvie) about

100 miles south of Forty Mile on the Yukon River.

It was from this establishment at Sixty Mile that

Harper and Ladue had grubstaked Bob Henderson, the seasoned Nova Scotian

prospector, who reputedly recommended to George Washington Carmacks and

his party to try what was to be the richest creek of the Yukon valley,

and who subsequently lost out himself. In 1896, having prospected for

two years along the Indian River, Henderson was working a creek which

issued from the same height of land (or dome) as did Gold Bottom and its

famous tributary, Bonanza Creek, known before the strike as Rabbit

Creek. It was on the latter that Carmacks, Skookum Jim and Tagish

Charlie, on Henderson's recommendation, panned out the gold which was to

give rise to the Klondike stampede. The story goes that, contrary to

prospecting ethics, Henderson was not immediately informed of the

strike. Unaware until the best claims had already been staked on the

creeks which lay over the watershed, Henderson never did become a rich

man. Yukoners consider him to be something of a tragic figure.

Ladue, who had been a prospector himself, had been

known to sit tight while others "rushed," impelled by the news of

promising new finds. His years of stampeding experience had gained him a

prospector's wisdom, if not the concommittant wealth.1 It was

perhaps less his experience than his mercenary instincts which moved him

to act quickly on this most recent strike. He hurried downriver to Forty

Mile to stake his own claim — though not on any part of the

gold-bearing creekbeds. Sensing the magnitude of Carmack's discovery,

Ladue intended to outstrip the entrepreneurs by laying claim to the only

land in the area which could serve as a possible townsite, 160 acres of

swampy flats at the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon rivers some 10

miles from Carmack's claim. There is a story that, on his downriver trip

to Forty Mile, Ladue met a Klondike-bound miner asking for lumber.

Figuring that prices for timber would soon surpass anything yet seen in

the Yukon, he immediately dismantled the Sixty Mile sawmill and shipped

it, together with all the dressed lumber he could find, down the Yukon

to the new townsite.2

By 1 September, a mere two weeks after the discovery,

the 160-acre townsite had been patented and was ready for

survey.3 The sawmill was reassembled immediately so that

building materials would be available before winter set in, and a

two-storey cabin was erected to serve as trading post and saloon. On

what was known simply as Joe Ladue's townsite, these were the first

stirrings of enterprise and civilization.

Although news of the Klondike strike spread like

wildfire inside the territory that fall, the secret was kept well from

the outside world. By January there were only four cabins beside Ladue's

on the townsite. As spring came, eight more sprang up, surrounded by a

collection of bedraggled canvas dwellings which increased

daily.4 It was not until 2 June that the AC Company steamer

Alice slid around the Moosehide bend.5 As the first

steamer to reach the Klondike that year, she was to carry out with her

the men whose arrival in San Francisco a month later was to trigger a

worldwide scramble for Klondike gold. Among these men was Joseph Ladue.

After spending half of his 43 years crossing the continent in search of

his particular paystreak, Ladue had finally found it. He named his 160

acres of paydirt Dawson City, after George Dawson, the Canadian

government geologist who had studied the territory in 1887.

There were some who, at the time, had suspected that

Ladue had fabricated a grand rumour about a minor strike in order to set

off a stampede in his region. But Dawson was no illusion, nor were the

crates of dust that accompanied Ladue and the other on the

Excelsior. While there were certainly those who thought that Joe

Ladue was not above such things, it was hardly the time to voice their

suspicions.

Before the hordes who would eventually pour into the

Yukon valley had time to drop whatever they were doing and set out "Ho!

for the Klondike!" the first steamers up the Yukon had already deposited

two influential entities at the Klondike's mouth. While they were

newcomers to Dawson, they were in a sense sourdoughs of long-standing

reputation in the Yukon valley. No one was surprised to see them among

the first arrivals. By early July, both the Alaska Commercial Company

and the North American Transportation and Trading Company had erected

stores and warehouses which became the focal point of Dawson's Front

Street. The AC Company's two-storied store (40 feet by 80 feet) upheld

the company's reputation along the Yukon for consistently putting up the

biggest building in each town. Adjacent to it were three corrugated iron

warehouses, another two-storey building which served as employees'

living quarters, and an additional warehouse. The next block had a

similar store, quarters and warehouse of the NAT&T Company.

Bearing in mind that newcomers from the outside did

not reach Dawson until the late summer of 1897, it is understandable

that the summer's commercial activity was relatively slow and stable,

carried out mainly by the two mercantile monopolies to provide for the

most recent placer congregation. Ladue himself recorded an absence of

competition. In another description of the town's business in the late

summer of 1897, there is no reference to any individual provisions

merchant.6 (Ladue was dealing almost entirely in timber.)

Prices were high, but neither inflationary nor unsteady (see Appendix

J). Ladue explained them: "In the present conditions of trade things

cannot be sold very much cheaper at a fair profit."7

The greatest problem facing the trading companies

— and a serious threat to Dawson — was the potentiality of

winter shortages and possible starvation in the new camp. During the

winter of 1896-97, for example, the North-West Mounted Police contingent

at Fort Cudahy, buying from both companies, had been forced to reduce

the basic flour ration.8 Some mines finished the winter with

flour and nothing else. Dawson itself had suffered one particular

shortage that winter, although not an acute one; there were no eggs.

(This shortage gave rise to a legend about Swiftwater Bill Gates. To

spite his unfaithful lover, Bill bought up the town's entire supply of

her favourite food, a very rare commodity, whole fresh eggs. If

Swiftwater Bill was as thorough in his retaliation as we are led to

believe, there was not an egg to be had in the entire camp.)

The situation in Dawson in 1897-98 was far different

from that experienced by the isolated community which had wintered there

the previous year. The community of 1896-97 had been made up entirely of

miners and prospectors already inside, experienced men of the north, who

knew the essential requirement of an adequate winter outfit. The local

population explosion of the late summer of 1897 (though it hardly

compares with that of 1898) was composed almost entirely of tenderfeet

from the south, men so smitten with gold fever that they had not

hesitated a moment before rushing north. Leaving on the first crest of

enthusiasm, they had neither help from published guides nor realistic

advice. They did not know how unwillingly the Yukon valley gave up its

gold, and with what ferocity its winters could punish the

improvident.

The very presence of these hasty and unprepared

arrivals was enough to dismay the head office of the AC Company. Such

impatience could easily lead to a "starvation camp," an irrevocable blot

on the company's record. As early as mid-July, the company's president,

Louis Sloss, made clear his concern to a San Francisco newspaper. For

any outfitter or steamship company to encourage a rush that season would

be both cruel and foolish. However sincere such promotion might be, it

would be responsible for the resulting deprivation in the Klondike, and

criminally responsible at that.9

Exactly how many ambitious Klondikers managed to

enter the territory before winter closed in cannot be determined. Nor is

it possible to know how many of them had winter outfits. Police

estimated that by 1 January 1898 there were almost 2,000 people in

Dawson and 5,000 in the Klondike region.10 At the beginning

of winter, starvation, or at least severe suffering, did seem likely.

Once again a dry fall lowered water levels on the shallow Yukon River,

cutting supply traffic short and prematurely ending the provision of

winter staples. By the end of September, the NAT&T Company had 400

orders yet to fill; the AC Company had received scarcely a third of its

paid consignments.11

Both companies traditionally received their stocks on

the basis of individual orders for outfits. Early in the season, the

consignee entered his name with the company and deposited half the price

of his outfit. While the two companies were faced with the same prospect

of shortage, their methods of dealing with the crisis differed. The AC

Company, which had enough material to outfit 1,252 men completely and

furnish flour to 1,589 more,12 chose to fill to the best of

its abilities all of the orders it had received. The NAT&T Company,

on the other hand, preferred to bypass its original orders and to ration

all its stocks on the basis of need.13 In October, when the

scare was at its worst, both companies were persuaded by the Mounted

Police and government authorities to fulfill their responsibility to the

worst-outfitted miners by offering transportation downriver to Fort

Yukon, where supplies were said to be more plentiful.14

Both firms did attempt to curb skyrocketing prices;

they eventually limited their sales to issues of supplies for two weeks

at a time, thereby controlling food speculation.15 Despite

their efforts, prices for flour, the most basic as well as the most

limited staple, ran wild on the black market. At midwinter the retail

price for flour seems to have ranged from $35 to $100 for a 50-pound

sack.16 Butter, when it could be had at all, was going for $5

a pound and salt for its weight in gold.17 Such prices put

these commodities beyond the reach of most buyers and turned their goods

into mere figures on the speculative market.

As winter drew to an end, it became clear that there

would be enough to go around and that Dawson would not starve after all.

Two unexpected factors relieved the situation: extra commodities were

thrown onto the market by people who left the district after freeze-up,

and those who stayed were blessed with an unusually mild winter. Indeed,

the Klondike Daily Nugget declared in comfortable retrospect

that, considering even the obvious cases of speculation and

inflation,18 the whole situation had been nothing but a

scare. Many placed the blame squarely on the two supply outlets which,

for all their protestations of innocence, were suspected of having

rigged the shortage for their own benefit. Those citizens of Circle City

who had made an orderly raid on the AC Company's steamer Bella in

the late fall were only too aware that their camp was being by-passed by

the company in order to get supplies through to Dawson, which lay

further upriver. They interpreted the company's intentions as pure greed

for the higher prices which undoubtedly prevailed at the newer camp. The

NAT&T Company suffered as much, perhaps even more so, from

accusations of unbridled favouritism in their rationing policy. The

Nugget was the community leader in its outspoken criticism of the

latter company, specifically of its manager, Captain J.J. Healy, for his

handling of the food shortage. Healy was accused of refusing to fill

some orders and then selling out such rare luxuries as molasses and

tobacco to favoured speculators at fabulous prices. Over the summer of

1898 the Nugget painted the picture in increasingly lurid

colours. The last instalment, released just before Healy was recalled by

the company in September, disclosed that the demi-mondaines and

"satellites who revolve in that particular sphere" had won Healy over,

while honest miners and small businesses had gone

short.19

Even those who denied that the situation had at any

time been out of hand could not overlook the prevalence of scurvy in

Dawson that winter. Limited and unvarying diets and poor-quality or

badly cooked food had been the cause. By breakup, bacon was the only

meat available; tinned vegetables had gone off the market early in the

season.20 Wherever the blame lay, a lesson had been learned

by both consumers and suppliers, who resolved to stock up the town's

warehouses over the coming summer. Further to ensure that the situation

would not repeat itself, the North West Mounted Police, who had kept

watch over the winter supplies, enforced a regulation made by

Commissioner Walsh that all men crossing the passes have at least 1,095

pounds of provisions to support themselves for a year's

stay.21

To everyone's relief, the winter of 1897-98

officially ended on 8 June with the arrival of the Mae West, one

of the steamers which had spent the winter locked in Yukon River

ice.22 Another good omen was the fact that her cargo included

whisky. At that point bars had been serving what amounted to

whisky-flavoured water; "thirsty" rather than "hungry" might be the best

description of the badly stocked town.

When the ice broke up and the steamers could move

freely again along the Yukon River, the news spread wide across the

continent and the great Klondike rush was on. Perhaps the most eager

were the thousands who had camped on Bennett Lake, impatiently awaiting

their chance to be among the first to grasp at the pot of gold.

Mixed in with the multitude were speculators and

entrepreneurs who had heard that Dawson was a starvation camp, that any

conceivable article could be unloaded on that desperate town at prices

unheard of in any previous placer camp. Such rumours seemed all the more

believable in conjunction with out-of-date reports which had come out of

the town the year before, before Dawson's first millionaires had left,

when there were still enough nuggets to go around. Such testimonials as

the following one, issued in June 1897 and republished later that year,

fostered the vision of Dawson as exceedingly rich and very hungry.

"There are more ways of making money here than any place I ever saw . .

. Big money can be made by bringing in a small outfit over the ice this

fall . . . I have seen gold dust until it seems almost as cheap as

sawdust."23

Since these individual businessmen were to some

extent in active competition with the already entrenched monopolies,

their greatest advantage in the battle for the market was timing.

Traditionally the first and the last boatloads of goods commanded the

best prices. There was, therefore, a rush of a specialized kind which

took place within the 5,000-craft armada in the great June boat race to

Dawson24 The goal was to be the first into town with the

goods and services which the population craved. The stakes were high,

but they were equalled by the risks involved. While the passes had the

advantage at first of being the fastest route to the Klondike (since the

Yukon's northerly mouth did not thaw for shipping until early July) the

probability of loss or spoilage over that precarious trail was

considerable. Costs were high, even though most of the traders built

their own scows. Early spring shipment by native packers from Skagway to

Bennett Lake amounted to about 12 cents a pound, and would increase when

the ice was replaced with the more treacherous spring mud.25

The chances of meeting disaster on the river were fairly good,

considering the unwieldy nature of many of the home-made craft and

scows. Miles Canyon and the Five Finger Rapids had become legendary

graves for men and merchandise, while the river's countless shoals and

sandbars were particularly hazardous in the early spring and late fall,

when the freezing of the river's tributaries lowered the water level.

The final risk concerned the market itself, the chance that it might

already be deflated by earlier arrivals. To the successful went the

spoils in the form of astronomical prices. The best-known example is

H.L. ("Cow") Miller, who sold the products of Dawson's first milk cow at

a phenomenal $30 per gallon.26 Ice cream was proportionately

$10 a glass. One dollar, the lowest negotiable sum, would buy a tin of

meat or potatoes or one piece of fruit — unless the fruit was one

of the few melons, which sold for $25 to $35.27 Two-fifty

would buy either a pound of butter or a dozen eggs, both at a fraction

of their winter values.28 Flour prices dropped dramatically

as soon as the first sack hit the wharf; the inflated market collapsed

and the price for a 50-pound sack plummetted from $50 to $12.50 to

$3.29 Tobacco, once completely off the market, had returned

to it and "Old Chum" cost 75 cents a pound and "T & B" cost $1.

Whisky was once again available at $15 per bottle (see also

Appendix J). Unquestionably, the summer of 1898 was a high point of

Dawson's commercial enterprise. Among the variegated memories of glitter

and mud, dancing girls and disappointed goldseekers, are the recurring

stories of the success and failure of enterprising individuals,

partnerships and multi-departmental companies. Like the miners they

supplied, they lived their Klondike adventure in the belief that gold

and initiative made anything possible. Yukon commercial activity was no

longer the domain of a few large companies that it had once been. Just

as the spread of the Klondike news had thrown open the goldfields to

masses of hopeful prospectors, so the field of merchandising attracted a

great number and variety of participants — large and small

enterprises, some with vast experience and others with none whatsoever.

Every miner entering the country bearing his required half-ton of goods

was a potential trader. The commercial spectrum of Dawson extends from

the large, established corporations to these individuals,

unintentionally involved, "swapping" their wares on the Dawson

waterfront.

Delving into the chaos of the Dawson marketplace that

season, one can discern certain formative trends. Certain general types

of merchant activity can be drawn from available examples. The first

type of merchandising to be considered involves the largest and most

influential mercantile interests in Dawson. These companies were able to

control all phases of the supply and distribution process, from their

purchasing agents outside, their sea coast connections at Saint Michael

and their river fleets to their storage and retail outlets in Dawson.

The first such companies to join the ranks of the existing major firms

were the Alaska Exploration Company (the AE Company) and the

Seattle-Yukon Transportation Company (the SYT Company). Based in San

Francisco and Seattle respectively, these firms announced their

candidacy before the first of their river steamers had left Saint

Michael bearing hundreds of tons of provisions, along with materials for

corrugated iron warehouses, stores and winter quarters.30 By

the end of August, notice of complete stocks in their warehouses

appeared in the Nugget.31 In the case of the SYT

Company, the mayor of Seattle, W.D. Wood, had resigned his post to come

north and personally manage the firm.32

On a smaller scale, but still in control of all

aspects of the trade, was the California-Yukon Trading Company. With the

arrival of her steamer Rideout proudly bearing 500 tons of

freight for the camp, construction was begun on warehouses and

wharves.33 From Vancouver emerged the British American

Corporation, a transportation company running two river steamers, which

in September bought out a local merchant and opened a store and

warehouses in Klondike City, the community across the Klondike River

from Dawson.34 Another well-known firm (though without a

river fleet of its own) was the Joseph Ladue Gold Mining and Development

Company. As president and managing director of the New York-financed

firm, Ladue made his final trip to his townsite in September 1898 for

the opening of the company's store. Dawson had become everything that

Ladue could have imagined when he first laid claim to the swamp. It was

to be his last impression of the place, for he died of tuberculosis

three years later.35 His firm opened its store by advertising

goods of the best quality, adapted to Klondike use, all at reasonable

prices. "Come and examine our flour, beans, bacon, sugar, eggs, butter,

teas, coffees, spices, canned fruits, dried fruits, tobacco, candies,

clothing, underclothing, boots, shoes, stationery, etc."36

The firm retained its founder's name, and survived Ladue by almost a

decade as one of Dawson's reliable general supply firms and steam

sawmills.

There was no doubt that the NAT&T and AC

companies still controlled the bulk of Dawson's trade. Tappan Adney

maintained that of the 7,540 tons of freight brought in on the lower

river route (via Saint Michael) by 1 September 1898, half was carried by

these two companies.37 By this time, the AC Company was

running a total of 13 steamers, and had four warehouses, one of which

was exclusively for warm storage.38 Their total capacity was

5,000 tons, but four more sheds were under construction. In reporting

the growth of these two companies over the summer of 1898, the Nugget

leaned heavily toward the AC Company. The newspaper's scathing articles

led one to believe that the NAT&T Company's sales had suffered

profoundly from the discredit earned by Healy39 but his

recall eased the situation.

The success of these companies in terms of their

prominence and popularity was largely due, according to the

Nugget, to their specialized consideration of the needs of the

miner. The three-storey AC Company building, an indisputably central

point in the Dawson business area, was organized on this basis. The

first floor had rows of offices where clerks dealt with the daily tasks

of outfitting, transportation, mail, cash and credit. Nearby were 22

safety deposit boxes of case-hardened steel set in a wall of masonry and

concrete. Beyond this opened up a veritable emporium, where "countless

shelves groaning under their loads"40 of staples and luxuries

were divided into departments according to the priorities of the

miner-consumer. First came the grocery department, then hardware, china,

glassware and drugs. The second storey had mens' furnishings, combining

standard heavy-duty Klondike clothing, robes and boots with "fancy and

dress shirts, beautiful neck wear of latest designs, knox and stetson

hats in assortments equal to any shown in the avenues of New York,

Chicago or San Francisco."41 A recently opened showroom

contained a housekeeping department as well as ladies' dry goods and

clothing. The newspaperman describing the store was highly impressed

with additional and separate facilities for delivery, for ice supply,

for warm storage (with accurate checking and a 24-hour guard) and for

the assaying and storing of gold. A final revelation was the clean and

comfortably furnished employees' residence. The author's concluding

comment on such large enterprises was that their impressive

installations reflected a "faith in the permanence of the country and of

Dawson in particular as a great distribution centre."

The second group of merchants to thrive that summer

often did interdependently with these companies. Although the large

companies retailed some of their goods in yearly outfit lots, they were

in effect wholesale firms as well. Through them, individual merchants

could purchase their goods, then have them shipped, stored and delivered

for further sale. Alternatively small merchants could buy the goods

through their own outside agents, then have them shipped on vessels

usually owned by these large companies. There were, in addition, several

independent river transportation companies which catered to individuals,

merchants and companies. On the lower river route, the Columbia

Navigation Company and the Empire Transportation Company (with a fleet

of 18 steamers) operated, making connections for Seattle at Saint

Michael.42 Goods could also be shipped in via Skagway,

connecting at Bennett Lake with either the Bennett Lake and Klondike

Navigation Company or the Canadian Development Company. Before long, a

fleet of scows was also operating regularly on this upper river route,

to expedite quick delivery of small consignments.

There is an understandable lack of information about

most of the 300 "stores and saloons" recorded in the police census of

July 1898.43 Those who advertised or were mentioned in

newspaper reports leave a hazy idea of the retailing practices of

Dawson's many individual merchants. Approximately 36 retail outlets for

general merchandise, groceries, dry goods, furs, wines, liquor and

tobacco (these three usually sold together in saloons and restaurants),

jewelry, house furnishings and lumber advertised in the Klondike

Nugget Over 20 others were mentioned in articles and reports. By the

end of the season the paper was singling out several individual

merchants whose impressive stocks implied that they were in Dawson to

stay. Among them was the partnership of O'Donoghue and Swift of

Kingston, whose lines of groceries, wines, liquors and general

merchandise were proclaimed outstanding in terms of quality and

selection. Their wares apparently included many articles not otherwise

obtainable in the city.44 The Macaulay Brothers were

similarly praised for their latest styles in dry goods as well as for

their complete stock of groceries. Their shelves contained such

delicacies as jams, jellies, pickles and olives, all of which would help

"to make the Klondike life something of a pleasure."45

A third kind of merchant was the small trader who

arrived in the Yukon with his own stock all ready to sell. He brought

his goods with him; consequently he was able to act independently of the

Dawson jobbers or wholesale firms. These traders have already been

introduced as they patiently waited for spring breakup at the head of

Bennett Lake. On one Yukon River boat it was later recorded, "the

majority of the 30 passengers were going into the interior to make money

through the sale of merchandise."46 Their stocks were small

(necessarily, for those crossing the passes), but usually highly sought

after for the luxuries they included. Fresh meat, fruit and vegetables

and dairy products were the most popular cargo — items rarely

included in the miner's own outfit and both risky and expensive to ship.

Once they had scanned the market situation, these traders could return

to their outside supply bases in the hopes of freighting in another

load. A particularly profitable enterprise that summer (and for long

after) was livestock. The animals could be herded overland on the Dalton

Trail, skirting the passes from the panhandle to Fort Selkirk on the

Yukon River where the trail met the upper river steamer route. Dawson,

the herders knew, was a seller's market.

One of the best known of these independent produce

traders was R.J, Gandolfo, an Italian fruit seller, whose first shipment

of eight tons of oranges, lemons, bananas and cucumbers arrived in an

untouched market at $1 apiece.47 Paul Mizony, whose father

carried in perishable stock over the same trail, recalls:

The prices we got for some of the articles were

as follows:

| potatoes | $1.00 |

|

| onions | .75 |

|

| eggs | 2.50 |

|

| butter | 2.50 |

|

| oranges and lemons | 75.00 | a box |

| canned tongue | 1.00 | a can |

Other items like canned jams, salmon, milk,

tomatoes and meat, brought like prices. Our perishables we sold at

wholesale, the other merchandise at wholesale and retail. Most of our

stock was sold out in about a weeks [sic]

time.48

These prices are only one example, providing a very

general picture of the situation. Uncontrollable price patterns marked

most of the summer of 1898.49 As a significant element of

Dawson's waterfront, the transient produce vendors were in later years

to become the bane of general merchant establishments and their stable

market conditions.

The final group of merchants (who never thought of

themselves either as a group or as merchants) comprised an unknown

number of men who never expected to earn their Klondike gold as traders.

Many an eager goldseeker who had hauled his required half-ton outfit all

the way to Dawson discovered that, while the cost of living was every

bit as high as expected, the rich claims needed to support it were no

longer available. He rapidly concluded that his outfit must be sold to

obtain the necessary fare to return home. One outfit was good

collateral, but many men amassed a number of them and temporarily became

small retailers themselves. The familiar Dawson sign, "$15,000 money

wanted — this entire stock to be cleared out at once — prices

very low"50 demonstrates that one man could become a

commission agent of sorts for several others sharing his desire to leave

as soon as possible. Any man who was willing to speculate in provisions

in order to raise enough capital to go into mining falls into this

category as well. Jeremiah Lynch's career is an excellent example. Lynch

began by buying up the flour in a consignment of goods which the AC

Company had turned over to the Bank of British North America when the

consignee failed to pay up. Lynch managed to sell the flour for $3 a

sack less than the prevailing price. With his profit from this

transaction, he came back for other staples in the same

consignment.51

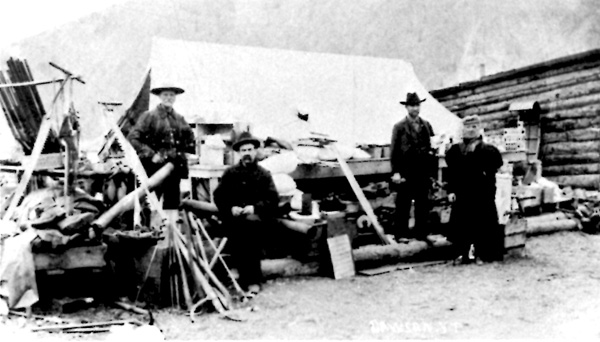

These entrepreneurs and impatient traders shared, for

the most part, a brief and disordered career in Dawson. The hectic,

bazaar-like atmosphere of their activity dominated many a first visual

impression of the city.52 The subject of a great number of

photographs, it presents a fascinating and detailed picture. Many who

arrived in small boats and scows never left the waterfront, where they

formed a "wobbly two-mile clutter from the mouth of the Klondike to

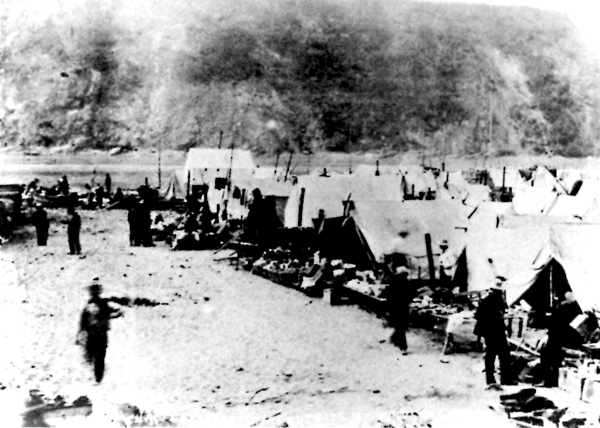

Moosehide Hill"53 (Figs. 18-19). A sand bar to the south of

the steamer landings was jammed with tents and scows so that there were

only two narrow thoroughfares to the water. Hastily constructed shelves

of planks and crates creaked with merchandise. The terms of purchase

were based on the best offer or, in many cases, on barter. Photographs

suggest that some booths specialized in certain commodities — case

lots of condensed milk, sacks of flour, boots, saws or rifles, for

example. One trader, by the look of his display, must have found argyle

socks particularly hard to sell (Fig. 20).

18 Scows along the Dawson waterfront.

(Public Archives Canada, PA 16182.)

|

19 Cheechacos "swapping" and selling out, Dawson, 1898.

(Public Archives Canada, PA 13432.)

|

20 An early "specialist" in dry goods, Dawson, ca. 1898.

(Public Archives Canada, PA 13490.)

|

As the season wore on, those hoping to leave tried

desperately to get rid of their goods. While provisions were still

limited and high-priced, dry goods of every description glutted the

market at prices slashed to half what had been paid for them in Seattle

or Victoria. In some cases that dealer had no choice but to auction off

his stock. For a month Dawson was witness to "boots and shoes and rubber

boots and the thousand and one things we all brought with us going at

prices which would make a Clarke Street Chicago second hand man sick

with envy."54 The out-of-here-or-bust mood prevalent in the

cramped canvas quarters was further encouraged by attractive newspaper

advertisements for immediate passage outside. In one instance a group

travelling out through the NAT&T Company got special rates 50 per

cent lower than the standard rates earlier in the

season.55

While Front Street remained the city's expensive

commercial "strip," newly erected structures were gradually creeping

along the cross streets (mainly York, King, Queen and Princess) to

Second Avenue, where land was cheaper. Summer traders, who had little

capital for land or lumber but wished to operate in this central

business section, often opened simple booths — canvas-covered log

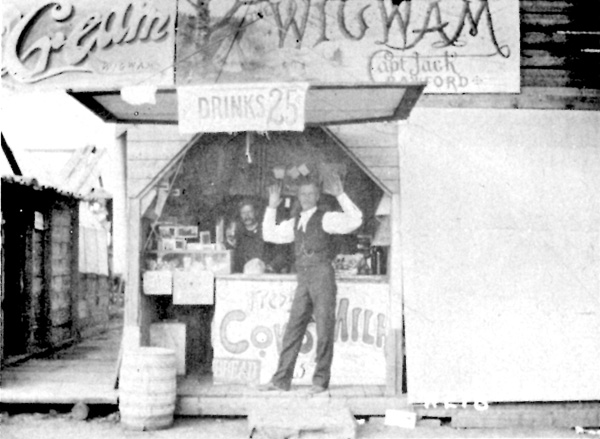

frames tucked away between two larger buildings (see Fig. 21). Gandolfo,

the fruit vendor, paid an astonishing $120 per month rent for 5 feet of

street frontage in his first quarters.56 Plate glass of any

kind was not to be had that summer, so booths and storefronts alike

opened right out onto the street or (in some parts of Front Street) onto

the sidewalk. Hooks, frames and cords were used as extensions of the

tiny interiors of such shops to hold and display all manner of crumpled

dry goods, used or warped tools and tangled tin masses of cooking

utensils (Figs. 22-26).

21 Captain Jack Crawford's store in Dawson, ca. 1898.

(Public Archives Canada, PA 16924.)

|

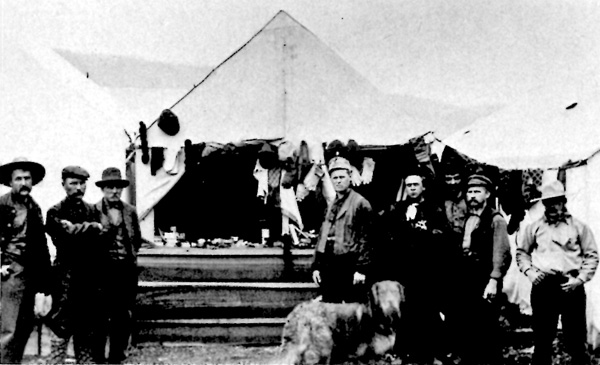

22 An early merchant, 1898 or 1899.

(Public Archives Canada, PA 13395.)

|

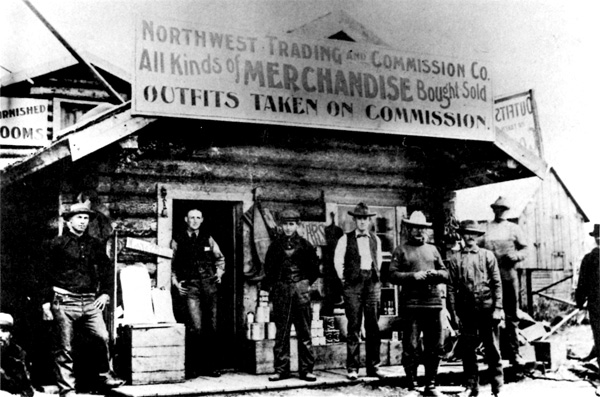

23 The Northwest Trading and Commission Company: "All kinds of

merchandise bought and sold," 1898 or 1899.

(Public Archives Canada, PA 13402.)

|

24 Reselling outfits at the Dawson waterfront, probably 1898.

(Public Archives Canada, PA 13501.)

|

25 "We buy and sell merchandise," 1898. Ben Levy was to become one

of Dawson's better-known clothing merchants.

(Public Archives of Canada, PA 13394.)

|

26 Selling out in Dawson, Asahel Curtis, photographer.

(Photography Collection, Special Collections, University of Washington Library.)

|

Against the dismantled Yukon stove or the sluice box

full of hip-length rubber boots leaned the proprietor. His waterstained

tent sometimes bore a hand-painted sign, or more often no sign at all

for his wares were known to all. He had lightered his own load onto the

beaches of Dyea, packed all 2,000 pounds of it over the Chilkoot, pried

it loose from the mud on the trail, and perhaps rescued it from one of

the shoals along the Yukon River, until at last he had reached the mecca

— Dawson, a muddy congestion of stumps, sawdust and dogs, populated

by innumerable cheechacos or tenderfeet like himself. This population, it

seemed, had one thought in mind: to get rid of the condensed milk and

the mackinaw suits to a luckier (or more naive) gold seeker who intended

to stay inside, and to return to the relative sanity and security of

Montreal or Seattle.

By the end of the shipping season (4 October that

year), the majority of disillusioned or homesick cheechacos had managed

to swap enough for a passage outside. Among those who had reason to

remain, there was an unquestionable confidence in the air. There would

be no talk of starvation in Dawson this fall. Well-stocked warehouses,

busy order offices and hurried autumn construction all reflected what

the Nugget termed the "faith of the moneyed men in the

Klondike."57 When Joe Ladue arrived in town late in August the

newspaper turned to him, as if for a patriarchal blessing. Ladue was

glad to oblige, and the Nugget reported that the city's founder was much

pleased with the growth and stability he saw around him.

The daily arrivals of loaded supply vessels over the

last months had allowed many a new establishment to blossom in elegant

premises. The Fairview and Aurora hotels and the Monte Carlo saloon were

known as Dawson's 'first class' establishments. For those who could

afford them, shipments of mirrors and mahogany replaced newspapered

walls and rough-hewn benches. By September two furniture stores were in

business, one offering "bed room suites, parlour, office, dining room

and saloon chairs, rockers, cobbler-seats, armchairs."58 In

addition to the already successful lumber trade, there was a burgeoning

tinware industry manufacturing pipes, fittings and, as winter drew

near, quantities of Yukon stoves. In this field McLennan and McFeely

were pioneers. They had lost no time in opening branches of their

establishment in Bennett and Dawson (Fig. 17). "Mc & Mc" was a

well-known firm in Vancouver, and this act of faith in the potential of

the district did not go unnoticed in the Dawson business community.

The two most significant features of the market at

the season's end were the greatly increased variety of available

commodities and the corresponding drop in prices.59 The price

of eggs settled at a respectable $3 a dozen, tinned fruit and vegetables

at 75 cents a can, bread at 25 cents a loaf. Tinned meat was expensive

— $2.50 a can — while potatoes were less than 50 cents a

pound, half their July price. While such prices were not necessarily

the cheapest such items had been, the arbitrary and fluctuating element

in the market had been settled.

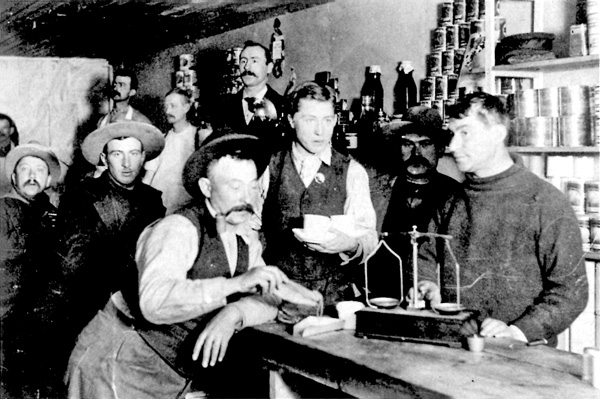

The multitudinous Dawson restaurateurs were among the

most astute observers of market fluctuations (Fig. 27). By the end of

the season, some of the more popular restaurants were reflecting the

time-of-plenty atmosphere with extensive and elaborate menus. For the

most part, though, there was little choice in which restaurant one

frequented. One weary customer reported, "You can eat anywhere. Its all

equally bad and dear."60 The average menu card ran as

follows:

| Sandwiches | $.75 | each |

| Dough-nuts | .75 | per order |

| Pies | .75 | per cut |

| Turnovers | .75 | per order |

| Ginger cake | .75 | per cut |

| Coffee cake | 1.00 | per cut |

| Caviare sandwiches | 1.00 | each |

| Sardine sandwiches | 1.00 | each |

| Stewed fruits | .50 | per dish |

| Canned fruits | 1.00 | per order |

| Cold meats | 1.50 | per order |

| Raw Hamburg steak | 2.00 | per order |

| Chocolate or cocoa | .75 | per cup |

| Tea or coffee | .50 | per cup61 |

27 Paying with gold dust, probably at one

of Dawson's early restaurants. Note the newspaper wall-covering.

(Public Archives Canada, C 5393.)

|

What form some of the more appetizing of these items

actually took is anyone's guess. One wonders, for instance, whether the

"caviare" was one of the dreadful pastes or tablets which had appeared

in the territory, suitably reconstituted. The stewed fruits were

probably evaporated ones, disguised, and the cold meats were undoubtedly

tinned. What was contained in the "Raw Hamburg steak?" In reporting

this menu, Tappan Adney registers his own doubts about the possibility

of creating these meals from the meagre pile of tins and bottles which

actually appeared on the shelf behind the counter. Eateries of this sort

sprang up across the town. While there are no references to deaths as a

result of their meals, the very experience must have given rise to a

number of unpleasant epithets as alternatives to "Paris of the

North."

Mercantile stability, the first signs of which had

been confirmed that fall by the town's founding father, was not easily

won. In Dawson itself there were tremendous physical obstacles to

overcome before the overgrown mining camp would give way to anything like

"civilization." Problems of health, sanitation, fuel and fresh water

supply, muddy thoroughfares and fire prevention gained increasing

newspaper consideration as winter approached. While the Yukon

Territorial Council was expected to deal with these urban problems, the

responsible merchants were acutely aware of the pressing need for an

active municipal organization. Incorporation of the city of Dawson was

the obvious first proposal, and was initially a popular one among the

city's commercial vested interests.62 Municipal taxation was

a fair price to pay for progress — improvements, protection and an

increased political voice.

The issue was given greater urgency when, in October

1898, a $503,000 fire in Dawson's business section levelled hotels,

saloons, stores and other businesses to frozen rubble.63 The

matter of incorporation would be tossed about for another four years

between Dawson citizens and the Yukon Territorial Council, where the

power to initiate the process resided. The merchants, represented after

August 1899 by the Dawson City Board of Trade,64 would not

always maintain the position on which they had united in the fall of

1898. Throughout these years the topic remained a lively one during the

dark winter days around the Yukon stoves. There it competed with the

gold royalty, freight rates, high prices, land speculation and newly

exchanged gold claims as the basis for opinionated discussion. Dawson

merchants turned their full attention to these concerns, alleviated by

talk about team sports, social functions and newly organized fraternal

orders in the days when the sun barely skimmed the top of the Midnight

Dome, the height of land overlooking Dawson from the east. For most of

the storekeepers who decided to winter inside, 1897-98 had been a

good season. Leather pokes and iron warehouses bulged alike, and there

was an optimism about the place which two major conflagrations could not

destroy.65 As far as anyone knew, the mother lode was still

to be found.

|

|

|

|