|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 17

The Halifax Citadel, 1825-60: A Narrative and Structural History

by John Joseph Greenough

The Very Model of a Modern Major General

I

Halifax felt the outbreak of the Crimean War almost immediately.

Troops from the garrison were dispatched to the front, as well as troops

which had previously served in the city; local civilians volunteered for

service, and Joseph Howe undertook to recruit in other parts of North

America in order to get volunteers to aid Britain. The citizens of

Halifax followed the fortunes of the British army with interest, and,

like most of the English-speaking world, they rapidly became aware of

conditions at the front. It was the first war in which newspapers

played a significant role in providing the civilian population with

detailed accounts of life in the army in the field, and the civilians

were, for the most part, horrified. The administrative machinery of the

British army had almost invariably faltered at the outset of previous

campaigns, but no one except the military and a few well-placed

civilians in London had known about it. But this was different. Every

newspaper reader knew about the breakdown of supplies, the horrors of

army hospitals, the bungling of the generals, and the other attendant

misadventures of the army in the field. The cry was raised for the

reform of the army. In the past, the antiquated and ridiculously

complicated military machinery had been well protected by the entrenched

interests of the officer class, the indifference of the politicians,

and the enormous prestige of the Duke of Wellington, who would consider

no change in the established order. But Wellington was dead: some of the

officers themselves favoured reform; and the politicians, goaded by the

public outcry, were thoroughly aroused. The administration of the army

was at least partly reformed. The public, including the good citizens of

Halifax, read in their newspapers of the changes. Those same citizens of

Halifax would have been amazed to learn that one of the very incidental

side-effects of reform was to be the last full-scale row over their

slightly dilapidated Citadel.

II

At the outbreak of the war, no fewer than 11 different ministries,

departments, agencies and boards were responsible for the administration

of the British army. The four most important of these were the General

Commanding in Chief, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies,

the Secretary at War, and the Master General and Honourable Board of

Ordnance.1 Without going into great detail, it is sufficient

to note that the Secretary of State, with his twofold responsibilities,

usually delegated military matters to the Secretary at War. The latter

was only infrequently a member of the cabinet, rarely an influential

politician, and, in practice, only had control over finance. The

relationship between the Secretary at War and the General Commanding in

Chief was made difficult by the fact that the latter's appointment was a

prerogative of the crown and no one had ever delineated the precise

relationship between the Commander in Chief and the cabinet. In any

case, the gentleman holding the office was usually more eminent than the

Secretary at War, who was as a result obliged to tread warily in

contentious matters. No Secretary at War, for example, would ever have

dared risk a major confrontation with the Duke of Wellington.

None of the above-named gentlemen had much control over the Master

General and Board of Ordnance. The Ordnance not only supplied military

equipment and built fortifications, it also ran what amounted to a

private army, in the form of the engineers and artillerymen. Some (but

not all) Ordnance officers held army ranks in addition to their

regimental ones, but their chain of command led directly back to London

and to the Inspector General of Fortifications (or, for the artillery,

the Director General of Artillery) who was in turn directed by the

Master General and board. This led to a ridiculous situation which has

been well described by the historian of the Royal Artillery.

The presence in every garrison of that band of conspirators known

as the Respective Officers, who represented the obstructive Board, and

whose opinion carried far more weight than that of the General

Commanding, was enough to drive that unhappy officer into detestation of

the Honourable Board and all connected with it.2

This, of course, was the reason why none of the commanding generals

in Halifax had ever interfered with the course of the building of the

Citadel, despite the fact that some of them must have been annoyed or

disgusted by the difficulties and crises of the 1830s and 1840s. Except

for authorizing the use of garrison soldiers for construction work, they

were almost as much spectators to the business as the civilians of

Halifax. Perhaps this had been at the root of the disagreement between

Colonel Nicolls and General Maitland in the late 1820s.

The reform of the army changed the entire situation. In August 1854,

the office of Secretary of State for War was created and that of

Secretary at War was abolished soon afterward. This meant that the

gentleman responsible for the army finally had major cabinet rank. Out

of deference to Lord Raglan, the last Major General, that office was

retained until his death in 1855, at which time it was abolished. The

Honourable Board disappeared at the same time. The administration of the

Ordnance passed to the Secretary of State for War, and military command

of Ordnance forces to the Commander in Chief.

These developments meant that the colonial detachments of the

Ordnance were finally incorporated into the same structure as the rest

of the army. The local Commanding Royal Engineers still reported to the

Inspector General (Burgoyne had enough prestige to survive the debacle)

but the local General Officer Commanding now had the authority to

countersign estimates, policy proposals and other major items. The two

chains of command ultimately went back to the same source: the Secretary

of State for War and the Commander in Chief. Moreover, the surviving

Fortifications department had lost much of its power and influence, and

the local commanders could easily go over the Inspector General's head.

Some of them proceeded to do just that.

The transition could not possibly have come at a worse time for the

Ordnance staff in Halifax. The General Officer Commanding in Nova Scotia

was one John Gaspard Le Manchant, who was also the lieutenant governor

of the province. A brief discussion on Le Marchant's personal history is

in order. He was a classic example of the problems of having a famous

father. The elder Le Manchant had had a brilliant career as a soldier.

He was something of a rarity in the 18th-century British army in that he

combined an ability to lead with a genuine interest in the theoretical

side of his profession. He had devised training procedures for the

cavalry and had been instrumental in establishing the Royal Military

College. He had helped to train an entire generation of young officers,

most of whom subsequently proved their worth in the Peninsular War, many

of them on Wellington's staff. He had also been acknowledged to be the

best English cavalry commander of his era. On top of all that, his life

had had all the elements of a romantic comedy. He had begun his military

career by challenging his colonel to a duel and had successfully

eloped. He was a respectable amateur artist and musician. He died

leading a successful cavalry charge at Salamanca, and Wellington

called his death a great loss to the army.3

The younger Le Marchant never attained the eminence of his father,

who died when John Gaspard was six. He too had gone into the army

— probably a mistake on his part — but unlike his father, had

had to purchase his promotions. The father had been a successful and

popular administrator; the son became a martinet. Eventually, after 26

years of service, uneventful except for a brief period in Spain during

the Carlist wars, he drifted into a career as a colonial administrator.

He was successively lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia (1852-57),

Newfoundland (1859-64) and Malta (1865-69).4 His

relative failure in the army rankled, and he rarely lost the chance to

make his military opinions known to anyone who cared to listen. When the

Nova Scotia Ordnance establishment came under his command in May 1855,

he was presented with a golden opportunity to make trouble, and he lost

no time in seizing it.

31 Major General John Gaspard Le Marchant, Lieutenant Governor and

General Officer Commanding, Nova Scotia.

(Public Archives of Nova Scotia.)

|

On 2 July 1855 Le Marchant addressed himself to the Secretary of

State for War on the subject of the Halifax defences. He was unsparingly

critical. In his opinion the city was rendered virtually indefensible by

the bad condition of all the principal works. He got in a dig at the

Respective Officers in true Le Marchant fashion: these officers had

undoubtedly performed their duties conscientiously, but the fact

remained that the works were in deplorable condition. The Citadel, he

noted,

though commenced in the year 1828 is still in an unfinished state,

and the Cavalier which has always admitted the Rain and which was

intended for the accommodation of 280 men is now

uninhabitable.5

The matter of the cavalier was something of a red herring; in fact

Colonel Stotherd had already dispatched a special estimate for

repairing and re-roofing the building.6 This had been

approved in record time, and authorization for the repairs was

dispatched on 28 July.7 Nevertheless, London put pressure on

Stotherd to explain the situation, and he did so on 26

August.8 He noted that the Citadel work was being held up

because the depleted garrison could not provide enough workmen, and, in

any case, there was not much work left. The parapets had suffered to a

certain extent from the cold of the preceding winter and the glacis was

unfinished. As for the cavalier, repairs were under way and would take

only two months.

The Ordnance annual estimate dispatched to London a month later

repeated the same point. There were seven items for the Citadel, only

two of which were for new work (the glacis and the parade). The

remainder were all for routine maintenance.9 The majority of

items in the estimate were of a similar nature. Stotherd wrote,

The services in Items 1 to 31 inclusive are for the most part

essential for putting the several defensive works in a proper and

efficient state, and for the due maintenance of the same in conformity

with regulations as also with the desire of His Excellency the Major

General Commanding.10

A few days later, Stotherd addressed a long letter to Burgoyne,

setting forth at length the condition of the defensive works in his

command. On the subject of the Citadel, he had comparatively little to

say; most of his comments concerned defects which would be remedied by

the approval of the estimate for the coming year. The only exception was

the old ironstone masonry in the escarp on the west front. This, he

admitted, was in poor condition, but it had stood for almost 25 years

and would, with care, continue to stand. He recommended pointing the

masonry to ensure its survival.11

Stotherd had a breathing space of a couple of weeks after Le

Marchant's first sally. He had, it seemed, met and survived the attack

— but this was true only insofar as he had answered general

objections. Le Marchant proceeded to change his approach. On 10 October

his military secretary sent Stotherd a list of questions directly

concerning the Citadel, and, on the same day, the general sent a copy to

Lord Panmure (the Secretary of State for War) in

London.12

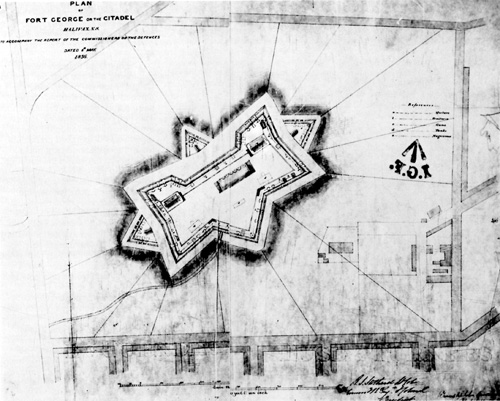

32 "Plan of Fort George or the Citadel," 1856. This plan was drawn to

accompany the final report of the 1856 estimate.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Why Le Marchant chose the Citadel as the focus of his complaints is

not entirely clear. Certainly the lessen defences, after a couple of

decades of neglect, must have been in worse shape. The most likely

explanation is symbolic: the Citadel was the most prominent work in the

general's command. Moreover, it had absorbed the greater part of the

money spent by the Ordnance in Nova Scotia for a quarter of a century,

and, should it prove faulty, would demonstrate that the old system had

indeed been inefficient.

Le Marchant's questions were specific. He wanted to know how long it

would take to finish the work: how many guns could be mounted; whether

or not the battery on top of the cavalier could be safely fired; the

quantity of water available; the length of time needed to complete the

glacis, and whether on not it would be better to complete it by

contract. He noted that the west curtain seemed, to his eyes at least,

to be completely rotten: that the cavalier was in such a bad state that

it was unsafe to fire its guns: that the redan salient was exposed

because the escarp was too low, and that there were faults with the

construction of the parapet and terreplein. He ended by requesting a

history of the work.

Stotherd replied on 22 November.13 Since most of Le

Marchant's questions were ultimately incorporated into the still longer

list which he presented to the commissioners in the following year, it

is unnecessary to quote at length from Stotherd's replies. The colonel

wisely attempted no more than direct factual answers, even when the

phrasing of the questions invited editorial comment or justification. He

produced elaborate calculations to demonstrate that the use of contract

labour in the work on the glacis would be more expensive than the use of

soldiers. This apparently convinced Le Marchant, for the question was

not raised again.

Having carefully done his duty, Stotherd sent a copy of his

correspondence with Le Marchant to General Burgoyne.14 The

Inspector General was infuriated by Le Marchant's treatment of the

colonel.

I regret very much that His Excellency the Major General

Commanding should have thought it necessary to adopt a tone of such

censure in the letter of the 10th October written by his direction to

the CRE, which by the explanation given by the latter appears to have

been quite uncalled for.15

Burgoyne realized the implications of Le Marchant's attack. Should

the general's allegations be substantiated, the whole business would

reflect badly on the Fortifications department, which was still

extricating itself from the wreck of the Board of Ordnance. The last

thing Burgoyne needed was a scandal. Even a minor one could do a great

deal of damage. From December on, he directed his considerable ingenuity

and influence toward defeating Le Marchant; but for the moment he could

do nothing directly. Everything depended on the attitude of the

Secretary of State for War. How seriously would Panmure take Le

Marchant's allegations?

The answer arrived on 28 December. Le Marchant's dispatches

containing his correspondence with Stotherd, which had arrived in London

in early December, had meandered around the War Office for a couple of

weeks and had finally been sent to Burgoyne with a request for a report

on the subject. This gave Burgoyne his chance. After 50-odd years in the

army, he was a consummate expert in the game of bureaucratic politics.

If Panmure wanted a report, how could he possibly fail to be satisfied

with one prepared by an entire committee of experts empowered to examine

the site at first hand? At one stroke Le Marchant would be prevented

from lodging more complaints and the whole business would be settled

quickly. The idea was immediately proposed to Panmure and was rapidly

accepted.16

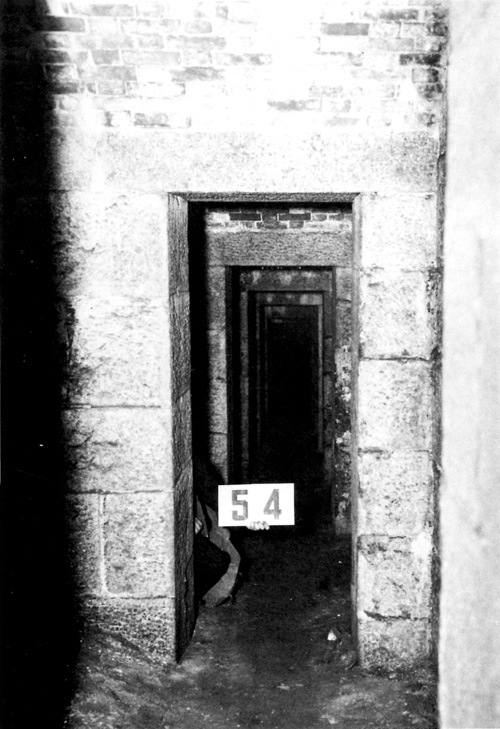

33 The counterscarp gallery opposite the south face of the raden, 1950.

This photograph was taken in the part of the gallery which runs under

the gate.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

The composition of the proposed committee was a work of art; it

presents a classic example of the manipulation of things in such a way

that nothing can possibly go wrong. Burgoyne proposed that the

commission be composed of the CRA and CRE in Nova Scotia, the CRE in

Bermuda, a naval officer, and an officer appointed by Le Marchant. The

importance of this selection lay in the fact that three of the five were

Ordnance personnel and the fourth (the naval officer) could almost

certainly be counted on to go along with the others. No matter what

attitude Le Marchant's appointee adopted, his was only one voice in

five. The scheme was plausible enough — the Ordnance officers were,

after all, the only experts available — and had an air of

impartiality. Le Marchant could hardly object to it. Burgoyne must have

been well pleased with his handiwork.

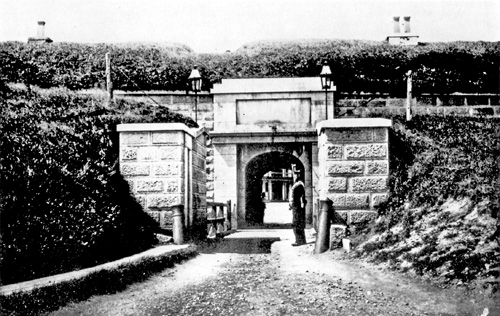

34 Photograph of the gate and bridge, ca. 1870. The post and chain fence

along the top of the counterscarp was installed in order to prevent

people (drunken soldiers being the worst offenders) from flailing into

the ditch.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Whatever his faults, Le Marchant did have enough political acumen to

give Burgoyne a run for his money. The committee was about the last

thing he wanted. Word of it reached him in February, and in the two

months remaining to him, he set about making as strong a case for

himself as possible. He realized that his only chance of making any

headway against a packed committee was to dig up something so scandalous

that the committee members, being officers and gentlemen, could not

possibly ignore it. He also realized, from Stotherd's answers to his

questions, that the majority of the points he had raised could be

satisfactorily answered. The one area about which Stotherd had been

relatively evasive was the state of the old ironstone escarps. Was there

something scandalous to be found there? On 9 March he asked Stotherd for

"the whole of the Contracts for the Citadel and their specifications" as

well as for information on expenditure oven the years.17

Stotherd — after telling Burgoyne about the request18

— promptly turned oven the documents in question. Among them were

the contracts for masonry let by Nicolls in 1829-30.19 These

suggested that there was indeed something to be gained by raising the

issue of the old masonry.

To ensure that the examination of the masonry in question was

thorough, Le Marchant requested that an independent expert, a Halifax

building contractor named Forman, be permitted to conduct his own

examination of the Citadel. Panmure agreed to the request.20

This may well have been a mistake on Le Marchant's part, since it

worsened his relationships with Stotherd and Burgoyne without gaining

much of a tactical advantage. After all, there were no fewer than two

engineers on the commission, and neither was likely to admit that a mere

colonial contractor knew more about masonry than they did. But the move

did ensure that an independent assessment of the work would be placed on

record and sent to London. It was a comment on the relative decline of

the Fortifications department that an army officer could successfully

impose such a condition. Nevertheless, the odds were still in Burgoyne's

favour as the committee began its deliberations on 24 March

1856.21

The five members of the committee were Stotherd, Lieutenant Colonel

Williams (CRE, Bermuda). Lieutenant Colonel Dick (CRA, Halifax),

Commander Shortland (Royal Navy) and Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Le

Marchant, the major general's brother. The committee was to answer a

total of 59 questions drawn up by General Le Marchant, and to give

recommendations for repairs, alterations and future works. Of the 59

questions, 27 were general, 10 concerned armament, 2 concerned

provisions, and the remaining 20 all concerned the state of the masonry.

The last were, of course, the most significant since they reviewed the

whole matter of the work done by Colonel Nicolls at the outset of the

building, and implicitly questioned the competence of Nicolls and his

immediate successors. They also raised issues which the Ordnance

department had not properly faced when it rectified Nicolls's mistakes

in the early 1830s. Specifically, they concerned the work done under

contract and the legality of the contracts themselves.22

The other questions were easier to answer. The beauty of Burgoyne's

scheme had, in part, consisted of the fact that it left Le Marchant to

draw up the questions which were to be put to the committee members.

Neither of the Le Marchants were trained engineers. In consequence, they

missed some extremely obvious defects in the plan of the Citadel.

Occasionally they noticed symptoms of the defects, but because of their

limited knowledge of the subject, their questions were not sufficiently

specific to force any admissions from the engineers on the

committee.

The best example of this involved the questions concerning the

exposure of the upper portions of the escarp in the redan and in the

western face of the north front. Such exposures were, in fact, the

result of the engineers' inability to form a proper glacis in these

areas, and had Le Marchant realized this, he might have gotten a

damaging admission from the committee members. As things stood, only the

two engineers on the committee knew the truth, and they were not about

to tell anyone. The exposure on the western side was explained away by

pointing out that there was no place in the vicinity where an enemy

could set up a battery and that the fort was well covered on the eastern

front, both from the ships in the harhour and from the guns of Fort

Charlotte. Similarly, the committee explained, the 8-inch gun at the

redan salient could not command the glacis immediately below it because

it was intended to cover the harbour. The committee did not feel obliged

to point out that none of the guns could command the glacis below

the redan salient because the slope was too steep.

The remaining general questions were even easier to answer, since

almost none of them raised serious objections; some of them, in fact,

were silly. The committee members were quite right to point out that at

no time was the cavalier intended as a keep and that it was erroneous to

consider it as one. Where Le Marchant did raise a legitimate question,

it was reasonably dealt with. Certain small errors in construction were

noted and alterations were advised but, on the whole, the committee

passed off Le Marchant's general questions without difficulty.

The questions on artillery and provisions also raised no important

issues; they merely served to get the answers on record. The masonry

questions, on the other hand, occupied a great deal of time. To answer

them, the committee was forced to call witnesses, collect legal opinions

and open part of the old masonry to find out whether or not it was

likely to remain standing. This took the better part of a month, and

resurrected events which had been forgotten for 26 years. In the end, Le

Marchant succeeded in at least part of his ambition; the workings of the

Ordnance department were examined by outsiders as they never had been

before.

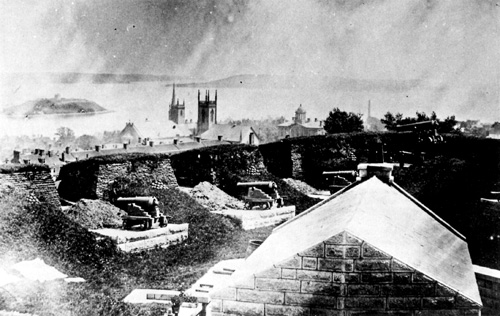

35 Photograph of the south ravelin ramparts, ca. 1870. This is the only

surviving photograph showing the original armament of any part of the

Citadel. The guns on the face of the ravelin are 6 ft. 6 in. 32-pounders

on garrison carriages, and the ground platform is of the type provided

for in the 1846 estimate. The gun mounted on a traversing platform at

the salient is a 9 ft. 6 in. 32-pounder.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Before this, no one had ever examined the Nicolls contracts. Were

they not, asked Le Marchant, "loosely drawn up and ill defined?" In

answering this, the committee called for opinions from three people, two

Clerks of the Works and Mr. Forman, the contractor appointed by Le

Marchant to make an independent examination of the masonry. The

committee posed three questions to Mr. Forman:

1. May not the [three contracts], be considered very

loosely drawn up and ill defined?

2. Would a practical and experienced person consider them

sufficiently binding to ensure the work being properly executed?

3. As a practical Man do you on reading the Specifications produced

clearly understand their meaning?23

Forman, in reply, noted that he "had found it necessary to be more

explicit" in his own contracts and had some specific complaints about

the wording, but, in general, was unable to come to any definite

conclusion about them. Mr. Gordon, a Clerk of the Works, found no

faults24 while Mr. Shiras, the second clerk, noted that

one clause provided for superintendance by the department:

I consider this clause . . . to be sufficiently binding, and that

by strict and due superintendence on the part of the Department, that it

would secure the Works to be executed in Accordance with the meaning of

the Specification, altho' the arrangements and provisions in its detail

are very different to that which must be introduced at the present

time.25

Shiras's answer raised the whole question of how closely the works

had been supenintended. Fortunately Richard Creed, a former Clerk of the

Works who had held the position during Nicolls's tenure, was still alive

and still in Halifax, and the measurement book for the period had been

located. The committee examined Creed as to its accuracy:

3. [Q] Are the entries in the Measurement Book now produced, in

your handwriting? —

3. [A] Yes.

4. [Q] Was an Officer of the Royal Engineers always present at these

Measurements?

4. [A] There was; — he always took the dimensions down in a

separate book which were compared with the entries in my measurement

book.26

The committee did not see fit to submit the contracts for the opinion

of a solicitor, and Le Marchant neither discovered the correspondence

between Nicolls and the Solicitor General of Nova Scotia on the

subject27 nor learned that the last set of contracts (1830)

had been let without tenders. On the basis of the evidence presented,

the committee was able to conclude only that "some of the clauses . . .

might have been drawn up with greater precision and clarity," and that

they were "sufficiently binding to ensure that the walls were built

according to the specification." Thomas Le Marchant disagreed, but was

forced to admit on the basis of Creed's evidence that he thought the

walls had been "actually built quite equal to the specifications."

In the course of collecting evidence, the committee discovered a few

odd facts about the methods of building employed by the department in

the early days. William MacDowal, a master mason who had been employed

on the works, testified that Nicolls had used masonry of lower quality

than was required later as a means of saving money, and that the working

season had usually gone on a month or so later than was needed for the

new work to set before the onset of the first frost.28 But no

really embarrassing facts emerged from the examination of the

witnesses.

The story of the failures was, of course, well known, and Le Marchant

made no attempt to exploit it. He was content to get it on record that

£17,585 11s. 2d. (according to the committee's reckoning) had been

spent on making the failures good. The committee also noted that "the

new work is of superior dimensions and quality to the old."

The critical question was whether or not the remaining

contract masonry could be expected to stand. This, the committee

established, included

About 3/4 of the Escarp wall of the South face, East Front: —

3/4 of the South Front; — about 1/8 of the flank of the South West

Demi-Bastion; — the whole of the West Curtain: — the flank of

the N. W. Demi-Bastion and the two faces of the North Ravelin:

— also 140 feet of the Counterscarp in front of the left Face of the

N. W. Demi-Bastion: —

To establish the condition of this work, the committee collected

opinions and made openings in two places. They concluded that

[these walls] are not in every respect well built; the facing

stones are in various instances unsuitable in dimensions for such walls.

—

They are of a weak profile being inferior to that which Vauban

prescribed, and are not in as satisfactory a state as the remaining

Escarp Walls built by the Department; yet as they do not appear to have

altered or bulged during the last 26 years . . . and being perfectly

covered from the foot of the Glacis, and only 3 feet of them being

visible from an eminence called Windmill Hill, . . . they could only be

breached from the Counterscarp, from whence the difference of time to

breach a good and a bad wall is a matter of only a few hours: — We

therefore recommend that they should remain for the present, being of

the opinion that with careful stopping and pointing . . . they are

likely to stand for many years. —

An opening made in the Escarp of the West Curtain and another in

the left Face of the South West demi-Bastion shew that the backing and

mortar are sound and good, the latter only, for about a foot inwards,

having been destroyed by the action of frost, owing to the neglect of

pointing.29

Thomas Le Marchant refused to endorse this judgement on the grounds

that Mr. Forman had not yet made his independent examination, and

complained that the other members should have withheld their opinion

until Forman had reported. His objections were noted, but the other

members declined to withdraw their observations, and there, for a short

time, the matter rested.

The rest of Le Marchant's questions about the masonry were easily

answered. The masonry work done by the department was, the members

considered, sound, although there were slight bulges in parts of the

interior retaining wall. As for the cavalier, the committee decided that

it was sound and could easily withstand the shock of having its roof

battery fired (although the members do not seem to have gone to the

extent of firing the guns to find out for sure).

The committee was concluding its deliberations when Forman's report

arrived on 1 May. Forman disagreed with some of the committee's

judgements, but not to any great extent. He considered the interior

retaining walls to be in a more serious state than the committee

admitted, and he took rather a dim view of the old masonry.

The rubble walls generally and especially the West curtain and

South front are in bad condition; the water percolates through most of

the joints; — they are pushed forwards and in many instances, the

stones have been forced out of the walls.30

Finally, he noted that the longitudinal walls of the cavalier had

"been lifted out of their original position and separated from the

arching abutting across the cross walls."

Forman had also opened several of the rubble walls — he does not

say which — and concluded that "the stones had not been skilfully

arranged, the walls not built solid nor proper precautions taken to bind

the work together," and concluded that "masonry in these walls cannot

last for any length of time."

The committee's response took the form of a brief rebuttal of most of

Forman's points. The tone of the reply implied that Forman, as a

civilian, could not be expected to know what a work of fortification

should look like. It was agreed that frost would eventually destroy the

contract masonry, but the committee was of the opinion that nothing

needed to be done about them "until more decided symptoms of failure

exhibit themselves." As for the cavalier,

the only lifting we have been able to discover is in two or three

upper courses of a 4-1/2 asphalted brick lining to the interior slope of

the top parapet, which lining the frost has fractured and rotted in

various places.

Similarly, the bulging in the interior retaining walls was due to

minor failures in the recess arches which the committee thought, could

be repaired only by expensive alterations.

Thomas Le Marchant, needless to say, disagreed with these

conclusions. He did not share the other members' opinion that the

interior masonry which had been examined was good, and he thought that

the old contract walls should be taken down and rebuilt "as soon as the

Citadel is in other respects perfect." He also noted that when the

ground at the foot of the recess piers in the interior retaining wall of

the south front was opened to examine the footings, "the hole filled

with water nearly to the surface of the parade," from which he inferred,

reasonably enough, that the works were "standing in water." The other

committee members pointed out that the ground was still saturated with

water from melting snow.

The committee's conclusions were numerous, but none was particularly

critical of the Ordnance department. The comments on the masonry (quoted

above) were allowed to stand; Colonel Le Marchant's objections were

noted separately. The committee recommended several things: the glacis

should be completed quickly; the brick revetments in the ravelins should

be removed: a couvre-porte in front of the gate should be constructed in

order to facilitate sorties: 68-pounders should be substituted on the

south salients; Addison's shot furnaces should be provided, and a few

other minor items should be taken care of. The report was signed by all

five members of the committee on 5 May.

Stotherd dispatched a copy of the report to General Burgoyne on 7

May.31 The Inspector General must have been pleased with the

results of his scheme. Although parts of the report could lead to

questioning, if they were examined more closely, and though some of it

shed rather an uncomplimentary light on the work done by the department

25 years earlier, it was, on the whole, a vindication. It stopped

further criticism and it effectively silenced Le Marchant. He never

risked another major encounter with Burgoyne during the remainder of his

term at Halifax.

One question remains for the modern historian: How much of the report

was whitewash? Considered in isolation, it would be difficult to

determine. But given the history of the work, given what we know about

the building done under Nicolls's command, it would seem reasonable to

believe Forman's assessment of the old contract-built walls; the

engineers on the committee had managed to cover up the facts, at least

partially. Fortunately there is enough evidence — sketchy as it

sometimes is for the later period — to reach a conclusion. The old

walls stood far longer than even the most sanguine member of the 1856

committee had any right to expect. Part of the south face of the

southeast salient had to be externally buttressed at some point in the

late 19th century, and ultimately had to be propped up with timber in

the 1930s, but the rest of the walls stood and still stand. Until it was

rebuilt in 1973-74, the west curtain remained more or less intact,

looking, one suspects, only slightly more decrepit than it had a century

earlier. (Now rebuilt, it probably looks better than it ever did.) In

most respects, then, it would seem that the 1856 committee members

acquitted themselves well; they salvaged the honour of the department

without greatly sacrificing truth.

|

|

|

|