Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 17

The Halifax Citadel, 1825-60: A Narrative and Structural History

by John Joseph Greenough

Imbroglios

I

Winter was usually the slack season for the engineering staff in

Halifax. The working season was over. The annual estimates were usually

completed before Christmas. There was little to do, except for the

administrative work necessary for the next working season which began,

weather permitting, around the first of May. In the early 1830s,

however, the winters were anything but normal. Christmas of 1833 found

the entire establishment — clerks, junior officers and draughtsmen

— labouring over yet another revised estimate for the Citadel, the

eighth in less than two years. By this time the work had become almost

routine. The calculations had been done many times before; many of the

necessary drawings were copied from ones made earlier for Boteler and

Peake. Even the order of the individual items was well-established. Any

novelty the work might have provided had long since vanished; all that

was left was simple hard slogging.

The new estimate, therefore, had something of an air of déjà

vu about it. Colonel Jones, who was ultimately responsible for its

formulation, fundamentally agreed with Boteler; the work had to be

completed along the lines originally laid down by Nicolls without making

sacrifices of strength or durability. He recognized that this would

entail spending more money than had originally been intended, and

faced this problem head-on in the opening paragraph of his explanatory

letter:

I have the honor to transmit the accompanying plan, and

explanatory Sections, showing the manner in which I consider the Work

can best be completed, together with an Estimate of the Expense,

Vt. £99,833 . . 2s . . 1 1/4d,

which I regret cannot be brought nearly down to the Amount of the

Original Estimate, without seriously compromising the Defensive

efficiency and General Protection which by the Original Instructions to

Colonel Nicolls, the Citadel at Halifax was intended to afford. . .

.

The enclosed Estimate . . . has been framed upon the lowest and

most economical Scale, and I know not how it can be

reduced.1

Anticipating critical comparison of his own estimates with Peake's,

Jones went on to reject the latter's proposals:

I cannot concur . . . concerning that it [Peake's proposal to

eliminate the eastern counterscarp] would actually impare the

defensive value of the Citadel, and also materially lessen its

estimation in Public opinion, a point of some consideration in erecting

a Work for the protection of a Town.

He concluded his introductory remarks with an acknowledgement of the

paternity of his proposals: "I have adhered as closely as practicable to

the original Project, and that of Lt Colonel Boteler for its

completion."

The estimate encompassed the completion of the three ravelins as

envisaged by the original plan. Accepting Boteler's and Peake's

arguments for caponiers. Jones provided for three of them, one for each

ravelin. The eastern front was to be closed with a redan which was to

extend "34 feet less than Colonel Nicolls intended but 16 feet further

than proposed by Lt. Col. Boteler." The counterscarp was to be built with

piers and arches instead of the continuous-arch gallery originally

proposed, since this would result in substantial savings. For the same

reason, Jones proposed to dispense with the countermines. In an

emergency they could "be readily branched out . . . in the requisite

direction through the openings to be left in the Walls of the Gallery at

proper intervals." Any savings from these two proposals would, however,

be more than swallowed up by the necessity of thickening the escarps

"nearly one half more than originally proposed." As for the earlier

failures, Jones wrote:

I coincide with Captain Peake in opinion, that the Masonry built

in 1829 must all be taken down and rebuilt to sustain the weight of a

Rampart. — But I think it not improbable that the portions of the

West Curtain and the Flanks recommended by Lt Col. Boteler to be rebuilt

may give way no further, and I should recommend their remaining

untouched.

The only really novel feature of Jones's proposals was the emphasis

he placed on casemates. He provided for no fewer than 27 new ones,

mostly on the north and east. His most striking innovation was his

proposal to casemate the redan as officers quarters. He had no doubts

that the problems associated with casemates could be successfully

overcome.

With due precaution and by adopting the expedients successfully

tried at other places; I have little doubt of being enabled to render

the Casemates sufficiently dry and in other respects fit for the

accommodation of Officers.

The provision of additional casemating rendered the cavaliers

superfluous, and Jones eliminated the northern and southern ones from

the estimate. The western cavalier, on the other hand, was already

largely built. Jones proposed to complete it as a barracks for 320

soldiers. He also proposed the addition of a casemate at each end of it

"to give the additional support it plainly appears to require before it

can be safely loaded with its Terreplein, or guns mounted on it."

The other major problem in the interior arrangement of the fort was,

of course, the magazine. Jones borrowed Boteler's proposal for two new

magazines, each consisting of a pair of casemates to be buried in each

of the western bastions.

II

With the arrival of Jones's estimate in London, the Fortifications

department finally had a coherent scheme to work with. Unlike the

previous plans, this one had been anticipated, and almost immediately it

began its slow progress through the proper bureaucratic channels. The

Inspector General was dismayed but no longer horrified at the prospect

of exceeding the original estimate. He recognized the fact that an

excess was inevitable. The whole approach to the new scheme reflected a

desire to investigate its component parts thoroughly and to insure that,

once adopted, it could be implemented without further embarrassment. A

copy of the new report was sent to the Master General and board as soon

as it arrived in England. On 15 May the Board of Ordnance issued orders

for the official submission of the estimate for its

consideration.2

The key document in the official submission was the Inspector

General's detailed commentary on the estimate, and this was dispatched

on 4 June.3 For the most part Pilkington was disposed to

agree with Jones's suggestions, although he had specific changes to

recommend in some of the items; for example, a different manner of

construction for the redan casemates and changes in the arches of the

two new cavalier casemates. He disapproved of the sunken casemated

magazines "because there is so much difficulty in affording them

sufficient ventilation" and recommended that they be "left open" (that

is, not covered by the ramparts). He thought that the retention of the

gallery through the whole of the counterscarp rendered all three

caponiers superfluous. He passed over the financial question without

comment, merely noting that the estimate required "£48,512 beyond

what Parliament have been told to expect for the whole," Pilkington was

not entirely satisfied with the estimate:

I have already stated that the Report of the Estimate is not

sufficiently explicit and full to admit of its minute examination, many

points of Specification are deficient and it will be seen that some

parts are provisional. — This I think unnecessary in the present

case, the intentions of the coming Engineer should be definite, founded

on the experience which this work has already afforded, and I therefore

propose returning the Estimate to Lt Coll Jones

for revision so soon as I am favored with the Master General's decision

on the Project.

The Master General's decision arrived within the month.4

The Ordnance clerks differed with those in the Inspector General's

office about the amount of the excess occasioned by the new estimate;

they put the figure at £62,000. Except for this detail, the Master

General found the estimate satisfactory. But there was a major

reservation. As a result of the excess, it would be necessary

to put the government in full possession of the circumstances

which have occasioned this great excess and to obtain the approbation of

the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury . . . before any further steps

can be taken on the subject.

A detailed examination of the Ordnance accounts had produced the

figures for the amounts already spent on the Citadel, but this was

insufficient. The Inspector General was, therefore, to

draw up a detailed Statement to shew how this great excess

has been occasioned [emphasis Byham's] — whether from

inaccuracy in preparing the original Estimate, — or from the

defective manner in which the Escarps were built by Colonel Nicolls,

— or from the alterations that have been made, and are

projected.

The statement was to be prepared as soon as possible so that "the

subject may be brought under the consideration of the Government."

Colonel Ellicombe replied to this missive two weeks

later.5 The Ordnance office and the Inspector General's

office were still at cross purposes about the amount of the excess, for

Ellicombe still calculated it at £48,512. Of this, £17,313

(Ellicombe explained) was for new services not provided for in the

original plan — the north and south caponiers, for example, and the

magazines, redan, casemates and so forth. Another £18,821 was the

result of "deficiencies in the original estimate" including the drains,

the increased size of the revetments and the necessary rebuilding. The

remaining £12,178 was the result of increasing the garrison from

320 men and 12 officers to 644 men and 19 officers. He concluded,

The excess on the original Estimate is to be very much regretted,

but with the exception of £6143 for a New Magazine, and the

expense of the Caponieres £1928 . . 14 . . 7-1/4. which might

probably be ultimately found unnecessary . . . the whole appears

unavoidable and shows that the original Estimate was much too low . . .

.

I would however . . . calculate on the necessity of providing for

the whole of the additional Amount . . . as the expense of this

important Work.

Ellicombe's letter demonstrated that the Inspector General's office.

at any rate, was completely convinced of the necessity of getting

additional funds. But the matter had passed entirely out of his hands.

The Inspector General was powerless to make major financial decisions,

or even to approach the Treasury directly for support. This was the

prerogative of the Master General and board. Those gentlemen were, by

now, thoroughly aroused. The board could hardly be expected to decide

about such a vital matter without first conducting an investigation of

their own and, with this decision, the first phase of the bureaucratic

process came to an end.

III

The new phase opened with an "Immediate" board order on 3

November.6 The Clerk of the Ordnance had finally agreed with

the Inspector General's Office that the new estimate would probably

exceed the old by £48,512. Part of the problem had been that the

amount of the excess could be calculated only if the exact amount

already granted for the Citadel were known and, while there was no

difficulty in ascertaining this figure, there was some disagreement

about the amount which had actually been spent. Specifically, there was

an unexplained difference of £7,659 between the amount which the

London office calculated had been spent by 31 March 1834 and the amount

which the Halifax office calculated had been spent as of 31 December

1833. A statement was appended showing the amounts calculated in

London,7 and the officers in Halifax were to comment on the

differences.

At the same time, the Clerk of the Ordnance had drawn up an extremely

detailed account of the expenses which had been incurred in the

construction. This detailed every last penny spent from 31 October 1828

to 22 March 1834 and took up 26 pages of close handwriting.8

The Respective Officers were instructed to compare this with the

accounts in Halifax so "a perfect uniformity may exist between the

accounts."

Halifax responded to this request with surprising speed. Statements

from the Respective Officers, dated 29 December, were dispatched by

Colonel Jones on 14 January 1835.9 The Respective Officers

found that the detailed accounts were correct in most particulars. A few

of the vouchers had been recorded inaccurately, but these all involved

small amounts and were apparently due to clerical

error.10

The difference between the calculations of actual expenditure

required a more complicated explanation. It was mainly due to two

factors. The expenditure had always been divided between sums spent in

the colony and sums allowed for stores sent from England. The accounts

for the latter were inconsistent because the Ordnance office charged the

full amount for good sent, while Halifax only invoiced the value of

goods received. As of 31 December 1833. £7,399 had been charged in

London as opposed to £3,242 invoiced in the colony. The difference

was largely the result of goods being damaged en route or not received

at all and included the sum of £422 for 20,700 large bricks

"thrown overboard on their way to Halifax" in 1830.11 The

other discrepancy was in the amount paid to the Royal Staff Corps

charged against the Citadel account. London had charged £10,216

while Halifax had charged only £7,404.12 The sum of the

differences between these two sets of figures, plus the £1,169

spent between 1 January and 1 March 1834, added £8,138 to the

Halifax calculations of overall expenditure. This narrowed the

difference between the Halifax and London accounts to £479 (the

Halifax calculations were now the higher of the two) and the Respective

Officers were at a loss to explain this discrepancy.13

But they did not leave matters at that, and after three months'

digging, finally unearthed the source of the trouble — two vouchers

which had not been properly recorded and cumulative errors in the

detailed accounts amounting to £1,478 3s. 0d. This brought the

discrepancy down to 17s., where everyone was content to leave

it.14 Whatever its other failings might have been, the

Ordnance department in Halifax had demonstrated that it could keep

books.

On 17 July the Clerk of the Ordnance pronounced himself satisfied

with the accounts.15 The gentlemen of His Majesty's

Honourable Board of Ordnance then paused to scratch their heads. If the

accounts were in order, then what could be wrong? "[Is] it possible,"

the Master General inquired on 19 August, "in any way to revise and

modify the estimate so as to reduce it nearer that originally proposed

and that without weakening the defences?"16

The new Inspector General, Sir Frederick Mulcaster, replied a week

later.17 He noted that, before 1825, over £300,000 had

been spent on temporary works on Citadel Hill, all of which had rapidly

vanished. The present fort, by comparison, would be permanent and, even

with the revised estimate, would cost far less than its predecessors. He

could suggest minor alterations in Jones's plan — the abandonment

of the caponiers, for example — but none which would result in a

drastic reduction in the cost of the work. He concluded,

Upon the whole therefore I am of the opinion that a great part of

the additional expense of £48,512 now contemplated, is unavoidable

if the permanent Work is to proceed to a state of defence. I concur in M

General Pilkington's report of 4th June 1834 which has been approved by

Sir J. Kempt19 and if the present Master General is of the

same opinion as to the eligibility of Lt Coll

Jones' Project as modified by the Inspector General, there appears to me

no other mode to pursue but to call for a revision of the Estimate as

proposed, and the whole subject will then be in a state to lay before

His Majesty's Government.

This judicious nudge finally got results. Mulcaster was to instruct

Colonel Jones directly to produce a revision of his estimate, and the

Master General promised in the interim to notify the Treasury to apprise

"their Lordships that a sum of about £49,396 . . . will be

required in excess of the original Estimate."19 The

instructions to Jones had barely left England20 when the

Treasury, having been informed of the case, reacted violently. Their

lordships flatly refused to sanction any additional funds beyond those

already approved, and demanded that the officer responsible for the

original estimate be called to account.21 The third phase of

the bureaucratic process had begun.

IV

By this time the process had begun to display a pattern. As each

government department became involved with the situation, it attempted

to deal with it in such a way as to minimize the impact of the problem

on its own day-to-day existence, The Fortifications office had attempted

to ignore the situation; the Board of Ordnance had tried to take refuge

in its own account books; the Treasury attempted to choke off the demand

for money. These initial negative reactions invariably provoked an

aggressive response from the agency which had raised the issue. In this

way the Commanding Royal Engineers, faced with the Fortifications

office's disbelief, consistently applied pressure; their aim was to

force the Inspector General to take effective measures to deal with the

situation. But once the process got above the level of the Inspector

General's office, it became more complicated. Once the Board of Ordnance

was involved, the Fortifications office became a sort of broker between

the Commanding Royal Engineers and the board, and the function of the

CREs became to supply the Fortifications department with sufficient

information to force the board to act. When the Treasury got involved,

the honour able gentlemen of the board be came the brokers and the

Inspector General's office took over the business of supplying enough

ammunition to enable the board to press the issue to a successful

conclusion.

This stage of the process began even before the Treasury's reaction

was known. Recognizing that the Citadel project was only one of a

multitude of matters under consideration by the Master General and

board, and a relatively minor one at that, the Inspector General's

office prepared a memorandum detailing the circumstances of Colonel

Jones's estimate.22 This was accompanied by a precis of all

major correspondence on the subject between 1828 and 1835.23

These two documents contained a distillation of the Inspector General's

case. and, since both Master General and board depended for information

and advice on the Fortifications office, it was inevitable that the

honourable gentlemen would present that case to the Treasury.

Having secured its flank with the Board of Ordnance, the

Fortifications department could only hope that Colonel Jones would

provide the necessary revised estimate as soon as possible. He did soon

2 February 1836.24 The covering letter was brief, Jones had

accepted all the major changes proposed in London and incorporated them

in his estimate. The caponiers were omitted; the redan counterscarps

were raised to 20 feet at the salient; the magazines were redesigned as

single-arch buildings, each enclosed by an area wall, and three

casemates were added on the north front. The saving amounted to only

£957 4s. 2-1 /2d.

There is no record surviving of the submission of the revised

estimate to the board. It must have been done almost as soon as the

documents arrived in England, because when the estimate was returned to

Jones for further revision on 17 July the comments of Mr. Cram, the

Surveyor of the Ordnance, were enclosed.25 Numbers of minor

revisions were requested. The Inspector General was of the opinion that

the buttresses to the magazines could be dispensed with and that the

main drain should have a concave floor. He also requested more details

about the gate and bridge and some additional information about missing

dimensions and so forth. Mr. Cram was more critical, but his criticism

was almost entirely directed toward specific instances of insufficient

detail in the estimate.

Jones made all the required corrections, and, for the third time,

sent the estimate to England. By then it was December. The estimate was

well on its way to its third anniversary, and progress toward its final

acceptance seemed minimal.

V

While Jones was revising his estimate for the second time, he was

also conducting a running battle on a second front with Colonel Nicolls

in Quebec City. This, of course, was the result of the Treasury's

insistence that the perpetrator of the original estimate be called to

account. As Jones knew more about the project than anyone else, the

burden of the dispute fell on him. One suspects, moreover, that the

Fortifications department preferred it that way; it gave the whole

affair the appearance of a squabble between two relatively junior

officers and deflected blame from the Inspector General's own staff.

Nicolls, predictably, defended himself and attacked Jones. Now that

London had decided that mistakes had indeed been made, the Inspector

General no longer felt it necessary to demand of Jones as he had of

Boteler, that the Commanding Royal Engineer in Halifax refrain from

exciting controversy. Jones was permitted to reply to Nicolls's comments

and by early 1836, the Nicolls-London-Jones correspondence had developed

into quite a considerable side-show.

Nicolls fired his first broadside on 23 November 1835. In a letter

addressed to Jones, but worded with the copy for London in mind, the

colonel defended himself.

I do not entertain the smallest doubt . . . I should have

satisfactorily completed the whole as estimated in 1825, with the

additional thicknesses, and moving the Buttresses nearer, as done in

1831, and these opinions are supported by the savings made on the

Casemated Cavalier built in 1830-31, . . . [and] on the Casemates

under the Ramparts . . . of which 10 were built, and 2 far advanced on

the £5404 granted for building.26

Without more information, he could not be specific about the reasons

for the additional expense, but he suspected that alterations in the

type and quality of materials and changes in the labour situation might

have been to blame. He also thought that

Much additional expense . . . has also arisen from the execution

of the Work passing from the first Projector [i.e. himself] ...

through 3 different hands ... whose ideas it is not to be expected would

exactly correspond, and even supposing them to be better than those of

the Projector, would cause additional expense, of which procrastination

itself is a great source.

He concluded with a request for more information.

Nicolls next addressed himself directly to the Inspector General,

sending a detailed commentary on the 1834 estimate.27 He had

many complaints. He had not resigned himself to the destruction of the

old magazine but, if this had to be done, he held that the replacement

should be built on the same site.

He considered the north and south caponiers useless and detailed his

objections to them. He thought that casemated accommodation would be

unwise "in so moist and variable a climate as Nova Scotia." He believed

the additional casemates at the ends of the cavalier to be unnecessary

for the reasons Jones had advanced — that is, to give the building

much-needed additional support — and he disagreed with the proposed

height of the redan escarp. As for the provision of additional barrack

space, he was of the opinion that there had been enough accommodation

allowed for in the original design, even for the expanded garrison which

was now considered necessary.

Shortly after Nicolls's letter was dispatched. Jones's detailed

account of work performed after Nicolls left Halifax arrived at

Quebec.28 This precipitated the most complicated exchange of

all. On 13 January 1836, Nicolls dispatched two detailed commentaries on

Jones's memorandum and a letter to the Inspector General, defending

himself and his original scheme.29 The commentaries were

promptly sent off to Halifax, and Jones lost no time in composing two

statements of his own.30 In this way the scope of the

controversy was limited to a fairly narrow area, the state of the work

in 1831-35 and the merits of the methods adopted by Boteler, Peake and

Jones himself during that period. But even this limited range was

sufficient to provoke the single most thorough discussion of the work to

appear during the entire history of its construction.

Nicolls's letter to Mulcaster is the least interesting of the several

documents involved in the exchange. In it he merely amplified the

arguments he had used in his earlier letter to Jones, blaming the

excessive spending on alterations in the work, the provision of

additional accommodation, the extensive use of granite and the frequent

changes of Commanding Royal Engineer since his departure. He still

maintained that he could have completed the Citadel for the amount of

the original estimate, and he contended that the £29,066 spent

between 1832 and 1835 had, perhaps, been badly expended; "[It] seems

very large for the services performed during these four years." This

last was the heart of his defence. It was not that he, Nicolls, had been

negligent, but that his successors had been inefficient.

Jones's memorandum of 16 December detailed the difficulties which had

arisen since 1831. He noted that almost no escarp wall had been

completed after that date, mostly because no agreement could be reached

on the dimensions of the new escarps. He detailed the troubles which had

unexpectedly developed when it was discovered that the foundations of

parts of the counterscarp had to be sunk far below the levels originally

intended in order to secure a solid footing. The excavations had

proceeded slowly because the engineers had not been able to form the

ramparts which would absorb the earth from the excavations. He noted in

passing that calculations had shown that the total amount of earth to be

excavated was insufficient to form both the ramparts and the glacis, and

that as a consequence, some earth would have to be hauled from

elsewhere. He dealt briefly with Nicolls's charges that he and his

predecessors had adopted more expensive methods.

On examination, the difference of prices between the two

Estimates, appear [sic] very immaterial.

With regard to the quality of the Materials, the only difference

is that a greater portion of Granite has been used than was at first

contemplated . . . but it is not considered more expensive than the iron

Stone for faced Work. —

The original Estimate was framed under the Idea of the Workmanship

being performed three fourths by Civil Artificers and one fourth

Military, and the labour altogether by the Military. — The

Workmanship of the present Estimate is calculated at the same rate, but

for the labour only one third Military, and two thirds Civil, from the

difficulty experienced in getting regular Military

assistance.31

Jones concluded by listing no fewer than 14 reasons for the

differences between the estimates, the bulk of them resulting from

additions to and corrections of the original project.

It would be futile to detail or even to attempt to summarize the

exchange between Jones and Nicolls which erupted over this memorandum.

The points in dispute were essentially technical, ("Should Col. Boteler

have sunk the foundations for the counterscarp opposite the North West

section to a depth of over 12 feet?" Colonel Nicolls asked. "Yes,"

answered Colonel Jones. "And in his place I would have done the same.")

Essentially Nicolls was trying to prove by example what he had charged

in his letter of 13 January to Mulcaster — namely, that his

successors had been inefficient and wasteful — and in so doing he

made a grave tactical error. As long as he confined his defence to

demonstrating that his original conception had satisfied all the

requirements of his superiors and answered all questions with general

replies, he was relatively safe. Instead, he chose to claim that he

alone could have completed the Citadel, and the claim would not stand

detailed scrutiny. Jones's replies were reasonable and satisfactory and

Nicolls's criticisms were more or less wholly refuted. He never again

was consulted on the subject of the Citadel.

At this point Colonel Nicolls departs from the history of the

Citadel. As far as can be seen the debacle did not have any adverse

effect on his career. His promotions arrived on the expected dates;

major general in 1837, lieutenant general in 1846, colonel commandant of

the Royal Engineers in 1851, and finally full general in 1854. He died

at Southampton on 8 September 1860,32 four years after the

major project of his career had been finally completed, 20 years behind

schedule.

VI

The absence of an accepted overall plan played havoc with the annual

estimates for the Citadel. In Halifax, Jones had no choice but to

continue bringing forward Citadel items in each annual estimate,

although, without a final decision about the eventual fate of the work,

it was becoming more and more difficult to find "safe" projects to spend

money on. Perhaps he hoped by attempting to keep expenditures at

near-normal levels to remind London of the need for haste.

London, however, could not be hurried. It responded to the problem in

an equivocal fashion; it continued to allow grants with each annual

estimate — possibly to allay suspicions in Parliament that

something was wrong — but insisted that Jones spend only the money

granted before 1834. Therefore, when Jones asked for

£11,143 10s. 8-3/4d. for the Citadel in the annual estimate for

183533 Mulcaster reduced it to £3,000 on the grounds

that the previous balances had not been expended.34 When

Jones asked whether this amount would also be frozen,35 he

was informed that the rule on expenditure still stood.36

A month later, the decision of the Treasury to limit expenditure

under the old estimate37 made the situation even more

difficult. The sum of £2,000 was granted on the annual estimate

for 1836 and it too was frozen.38 The situation in Halifax

was becoming desperate. At the beginning of the 1836 working season, the

unexpended balance on the grants for 1828-33 had stood at

£2,88039 and was declining rapidly. By August the total

had fallen to £700 and Jones warned London that, unless more funds

were forthcoming, all work would stop on 30 September.40

At this, London was finally forced to relent. Ellicombe recommended

that "the Commanding Engineer . . . be authorized to charge the vouchers

. . . to the votes referred to [i.e., 1834-36] as soon as the money

on previous votes shall be wholly expended" and to "proceed with such

parts of the work on which no alterations is [sic]

contemplated."41 The board agreed and issued the appropriate

orders on 30 September42 — the day the money ran

out.43

Even this was only a temporary relief. When Jones included

£5,814 13s. 8d. for the Citadel into the 1837

estimate,44 London deleted it altogether,45

completely drying up the Citadel funds. At that point there was a total

of £16,008 left in unexpended balances.46 Normally this

would have been spent in a single season, but conditions were by no

means normal. To all practical intents and purposes the works were

paralyzed by the absence of a coherent policy. As a result in the period

from 1833 to 1837, little was spent and less was done.

By the summer of 1838 it was abundantly clear where the bottleneck

was. The Treasury showed no inclination to hurry. Worse, the board had

more or less abandoned the struggle, leaving Mulcaster to fight on as

best he could. On 6 July he once again submitted the revised estimate to

the board for transmission to the Treasury, along with related

documents including the correspondence with Colonel Nicolls and Jones's

commentary thereon.47 He noted that the estimate had been

revised

with reference to ... the Reports of my Predecessor and myself . .

. both at the Station, and, (so far as it has been practicable to do so

from the information afforded) in my Office —

He admitted that there were still some minor omissions, but hoped

that these would be covered by the one-tenth contigency provision (a

provision by which one-tenth of the total amount estimated for was added

to the total as a margin of safety). The final amount of the estimate

was set "in round numbers [at] £102,500, which will be about

£51,000 beyond the [present estimate]" and he recommended its

acceptance.

On the same day, the board slid a discreet knife into Mulcaster's

back. The Surveyor of the Ordnance drew up his own assessment of Jones's

work, and he was far more critical than Mulcaster. He wrote,

I am induced [?] to consider that the present estimate could not

be looked upon as a complete Document upon which to form a conclusive

opinion of the actual expense of the Works.48

The Treasury took almost five months to respond to these documents,

and even then its response was equivocal. Colonel Nicolls's objections

were cited as the major reason for returning the estimate to the board

for further consideration.49 But what more could be said

about it? Mulcaster made one last attempt, and produced the most blunt

of his many letters and memoranda on the subject.50 Angry

because the Treasury had cited Nicolls's objections in their minute of 30

December, Mulcaster finally and unequivocally put the blame for the

excessive cost on Nicolls. The excess had been the result of

1st The original project being incomplete.

2nd The Estimate insufficient. — and

3rd The failures (from insufficiency) of the

Revetments.

The Treasury had used Colonel Nicolls's comments to object to the

alterations made in the original plan. Mulcaster retorted acidly:

The Lords of the Treasury appear not to have adverted to the fact

that the alteration of the Plan was first suggested by Colonel Nicolls .

. . in his report dated the 5th Septr 1831, and

the failures of the revetments were also received from that Officer.

— Hence it is erroneous to question his opinion as to the

"propriety or necessity" of the measures of improvement. It may be

inferred that Colonel Nicolls does not coincide in the details of the

measures, but they have been considered by the two late Inspectors

General as well as myself and approved by Sir Jas Kempt and I am

prepared to justify their necessity . . . from the insufficiency of the

original revetments planned by Col. Nicolls, and the omissions in the

original Estimate framed by that Officer.

This time it took the Treasury only two months to decide. On 27

March, Spearman notified Byham that "their Lordships will not object to

sanction the expenditure of such sums as may be granted by Parliament

for this work."51 On 4 April word of the decision was

forwarded to Halifax.52

The approved plan which finally emerged from the long controversy

closely resembles the Citadel as it now stands. Several of the

components of Nicolls's original design were dispensed with altogether

and many of the rest were substantially altered. The north and south

cavaliers and the old magazine were the most prominent casualties. The

old magazine was to be replaced by two new ones, one in the gorge of

each of the western demi-bastions. The counterscarp and redan were both

altered, the former by changes in the design and the latter by the

addition of dwelling casemates. The changes in the counterscarp design

eliminated the casemates of reverse fire and all of the countermines on

the southern and eastern fronts.

VII

The Treasury's decision had come very late. While it was trying to

make up its mind, Jones was becoming increasingly strapped for money.

He asked for a mere £4,474 7s. 3-3/4d. for 1838.53 By

the time the Board of Ordnance got round to acting on his request, the

Treasury order had been passed. But the measure had yet to come before

Parliament, and the most that Mulcaster could recommend was

£2,000.54 By this time the total unexpended balance was

down to £7,51655 and was still falling. The next year,

the crisis finally having passed, Jones asked for £24,093 7s.

2-1/2d.56 The board allowed him £5,000.57 to

which he could add an unexpended balance of £1,225.58 A

year later, all but £135 of it had been spent.59 and

Parliament finally granted a healthy £10,000.60 The

tempo of building returned to something approaching normal. The

financial drought was over, and Jones was finally getting the chance to

implement his plans after six years. As if to seal his success, he was

given permission to remain on the station to finish the

project.61

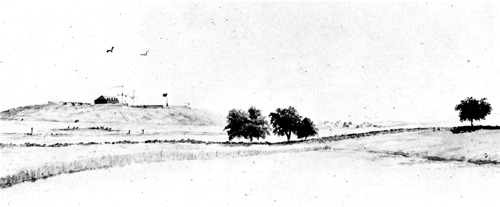

13 "Halifax Citadel and Common from Cogswell's Barn, near the Haunted

House, 21st August, 1840." Watercolour by Colonel Mercer. Viewed from

the northwest, the Citadel already looked rather imposing. A view from

the east would have given a different picture. The eastern front was, at

the time, barely started.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

|