Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 17

The Halifax Citadel, 1825-60: A Narrative and Structural History

by John Joseph Greenough

Colonel Nicolls's Citadel

I

Although the genesis of the design for the present Citadel seems

straightforward enough at first glance, the circumstances surrounding it

are, in fact, rather obscure. A careful reading of the relevant

documents reveals an essential uncertainty of purpose in the writings of

the principals responsible for the design. Had the work been

successfully completed without any major mishaps, the ambiguity

surrounding its birth would be of no more than passing interest. As it

happened, the adoption of the initial plan for the Citadel led directly

to a decade of failure and confusion, and the origin of the trouble lay

in the uncertainties evidenced in its inception and in the characters of

the two men most directly responsible for it.

3 Colonel Gustavus Nicolls, RE. Portrait by his wife.

|

The first of these two was Sir James Carmichael Smyth. He and his

fellow commissioners had the sometimes unenviable task of producing a

coherent and reasonable general scheme in keeping with the framework

laid down in the Duke of Wellington's 1819 memorandum and in his

instructions to the commission. The major problem was that Wellington's

instructions, though brief, were far too detailed. The duke was

attempting to settle the defence of a country which he had never seen.

Although his grasp of the overall strategic problems involved in the

defence of British North America was sound enough, he faltered —

sometimes badly — in his assessment of the value of specific

locations. In fairness to Wellington, one ought to point out that he

invariably phrased his suggestions in such a way as to give the

commissioners the widest possible latitude in making their decisions.

The problem was that Smyth and his fellow commissioners, in most cases,

treated these suggestions with a reverence which their Victorian

descendants usually reserved for Scripture. It was perhaps too much to

expect that any engineer officer, no matter how competent, would have

dared to contradict the duke himself but it would have been better if

Smyth had displayed a little more independence in carrying out his

commission.

This absolute devotion to Wellington's ideas was not, in itself,

entirely bad. Smyth, however, combined it with an incurable optimism in

estimating the amounts of money needed to construct the various works he

recommended. It is difficult to be precise about the extent of his

optimism, since so few of the works recommended were actually built, but

it is worth nothing that in almost all cases the amounts estimated by

the Commanding Royal Engineers (CREs) on the spot exceeded Smyth's

figures (see Table 1). Those works which were finally constructed

all cost more — some of them far more — than the figures

proposed by the commissioners. Smyth was, by all accounts, a competent

officer, so one is at a loss to account for his poor judgement. Perhaps

he was merely ignorant of Canadian building conditions. Possibly the

unrealistic estimates reflect Smyth's familiarity with political

conditions in England and his awareness that excessive costs would deter

Parliament from accepting his recommendations. In any event, the

optimistic estimates contained in the final version of his report were

to have serious consequences in the subsequent history of the Halifax

Citadel.

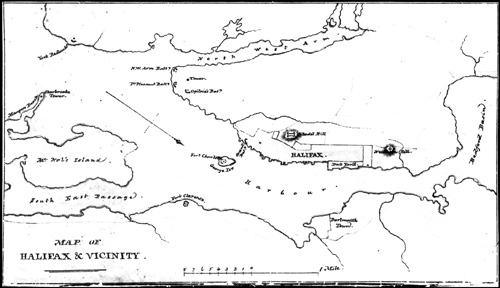

4 "Outline map to illustrate a Report to His Grace the Duke of

Wellington relative to His Majesty's North American Provinces" (1826).

This map was inset in a large map of British North America drawn to

illustrate the provisions of the Smyth report. It illustrates the

relationship between the Citadel and the town and harbour batteries. The

citadel was too far north to be of much use in defending the harbour and

inconveniently situated for the landward defence of the town. The map

shows clearly why a supporting fort on Port Needham Hill (north of the

Citadel) was thought necessary.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Smyth's weaknesses were neatly complemented by those of the engineer

officer most directly concerned with designing and constructing the

Citadel, Colonel Gustavus Nicolls. Nicolls and Smyth had much in common.

Both had enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1794 and had transferred to

the Royal Engineers in the following year. Both had risen through the

regimental ranks in identical stages until 1813, when both were promoted

lieutenant colonel. At that point their careers diverged dramatically.

Most of Nicolls's career had been spent in colonial postings. He missed

the opportunities afforded to officers who had had the good luck to

serve in the peninsular campaigns and at Waterloo, with the result that

he was still a colonel in the Royal Engineers — a mere major in the

regular army — in 1825. Smyth, on the other hand, had attracted the

patronage of the Duke of Wellington, married very well and, as we have

seen, served with distinction in Europe and had been at Waterloo. By

1825 he was a major general in the army and a baronet.1

Nicolls may well have resented his contemporary's striking success, but

his resentment was either tempered or hidden by a well-developed sense

of humility.

Nicolls's letters to his superior officers make interesting reading.

He never contradicted. He greeted suggestions with praise and gratitude.

He was deferential and complimentary. He never ventured to criticize. He

was quite capable of calling the attention of "His grace the Master

General" (Wellington) to the fact that the neck of the Halifax isthmus

bore "so strong a resemblance to the lines of Torres Vedras (that so

effectively put a stop to the success of the French in Portugal ...)"

that he could not "refrain from noticing it."2 Occasionally

this weakness completely usurped his better judgement. In 1830, Lord

Beresford (the Master General of the Ordnance at the time) differed with

Nicolls's strategic assessment of a local prominence known as Cape Hill

near Annapolis Royal. Beresford based his objections on a vague memory

of the geography of the place; he had served there as an ensign

forty-odd years earlier.3 Nicolls, whose acquaintance with

local conditions was of a decidedly more recent vintage, did not venture

to disagree. Instead he drew up plans for a work for the hill which he

took the liberty of "naming Fort Beresford . . . it having emanated from

His Lordship's recollections from having quarters at

Annapolis."4

Gustavus Nicolls, therefore, was the last man either to resist the

suggestions or to contradict the financial judgement of Sir James

Carmichael Smyth, especially since the latter had the backing of so

formidable a figure as the Duke of Wellington and good relations with

virtually every senior officer in the engineer corps, from the aged

Gother Mann (the Inspector General of Fortifications) on down. Picture

the two men touring the defences of Halifax in the late summer of 1825,

Smyth suggesting, Nicolls agreeing and enlarging on the suggestions.

Between them, they fathered the present Citadel. They were also largely

responsible for the disasters which befell their inadequate and slightly

peculiar offspring.

II

In the case of the Citadel, Wellington presented the commissioners

with the most ambiguous of his suggestions:

It would be most desirable to look at the ground upon which Fort

George at Halifax, now stands, with a view to either its reform or the

construction of a work of larger capacity upon that ground by way of

keep to the works destined for the defence of the harbour, which might

be garrisoned by two or three hundred men.5

This contradictory passage reveals the duke's fundamental uncertainty

about the strategic value of the hill in the overall framework of the

Halifax defences. It appears to suggest that the Citadel was less

important than the harbour defences. On the other hand, it does not

reject outright the possibility of a major building on the site. But it

does indicate that Wellington had in mind a modest work, and it does not

explicitly mention the possibility of permanent construction.

When Nicolls and Smyth came to consider the duke's recommendation,

they decided that a "work of larger capacity" was clearly called for. To

make a case for such a work, a variety of reasons was given. The

commissioners argued that a work on the hill would

[protect the town] . . . support . . . the sea batteries. . . .

give confidence to the troops and militia advancing to meet an advancing

enemy, and . . . enable the General Officer in command to move to any

other part of Nova Scotia with his disposable force . . . without

exposing his stores . . . to be taken and destroyed.6

Smyth himself added the argument that expenditure on a permanent work

would, in the long run, be cheaper than piecemeal expenditure on

temporary fortifications.7 He also elaborated on what, in his

opinion, was the nature of the threat to the town.

In Canada and Halifax the enemy is at our door. If our minister in

Washington is deceived, if our generals are indolent or supine, a war

may be declared and an invasion take place before the ministry in

England are aware that hostilities are even contemplated. The

construction of the fortress as proposed becomes consequently more

urgent and in dispensible.8

Nicolls's contribution to the debate was phrased in his usual

mannor:

Sir James C. Smyth has assigned several good reasons for the

construction of a work on Citadel Hill, — I will take the liberty

of adding one more, — viz, the good effect it would have on the

Morale of the natives, as well as the contrary on that of their

neighbours the Americans, who when on their frequent visits to this

harbour, see its shores bristling with cannon on every side, and the

British flag flying on the Citadel, on a fort respectable and strong for

this side of the Atlantic, are thoroughly deterred from making an attack

on Halifax.9

Despite its language, Nicolls's explanation of the reasons behind the

building of the present Citadel is the only one which makes much sense.

None of the explanations dealt at any length with the strategic value of

such a work, and indeed the meager explanations which were offered were

contradictory. In an era when the largest gun in common use in the

British army had a maximum range of just over 3,000 yards,10

the Citadel could not effectively support the sea batteries. A gun

mounted on the extreme southern end of the hill could only mask Georges

Island and the middle reaches of the harbour — neither of

which was an important factor in the event of a sea-borne attack. Nor

was the hill in itself particularly well situated to defend the town

against a land attack. Nicolls himself admitted that the first line of

defence against such an attack would be the neck of the Halifax isthmus,

which was out of sight of the Citadel.11 The commissioners conceded

that the hill could be properly defended only if it were supported by

temporary works on adjoining high ground (notably Fort Massey Hill) and

a permanent work on Needham Hill to the north.12

The best that could be said was that the Citadel, supported by the

works described above and by a field army, could assist in the defence

of the town against a land attack, and in this sense was intended as a

keep. However, "keep" can mean any work, from a blockhouse on upward,

and one wonders if perhaps a less elaborate work (like Captain Fenwick's

towers) would not have served the purpose equally well.

No one connected with the project, with the possible and ironic

exception of Nicolls, ever seems fully to have understood the fallacy in

the strategic reasoning behind it. There is no evidence, at least in

North American documents, that any questions were raised about the

scheme, except in terms of purely technical aspects of the final design.

Wellington's tentative and ambiguous assessment of the value of a work

on the hill was accepted, and the commission recommended, without

reservation, the present work on Citadel Hill.

III

The actual design was Colonel Nicolls's work. It is impossible to

determine how much of it was contributed by Smyth and his fellow

commissioners; their report is not sufficiently specific. They

pronounced themselves in perfect agreement with Nicolls on the

principles upon which he proposed to base his design, and enjoined him

to submit plans and estimates at his "early

convenience."13

The commissioners did, however, impose two restrictions, both of

which were to have serious consequences. The first involved the question

of the labour force for the new work.

[Colonel Nicolls] states that in turning the arches and other

important parts of the construction of a fortress, which require great

attention and superior work, he would prefer not employing contractors.

. . . We . . . agree with [him] that it will be desirable to

employ a company of Sappers in Nova Scotia, but we still recommend that

whatever can be done by contract should be agreed under proper

securities and subject to a vigilant

superintendance.14

This decision led directly to the employment of contract labour in

the building of the escarp walls, which was to have dire consequences a

few years later.

The second restriction imposed by the commissioners was concerned

with the estimated cost of the work. The commission decided, with its

usual optimism, that the fortress would cost about

£160,000.15 Most of the other engineers involved in the

design of works recommended by the Commission blithely disregarded the

commissioners' estimates, but Colonel Nicolls was of a different nature.

He adhered to the estimates so scrupulously that he found himself forced

to compromise in fundamental matters of design in order to keep the

costs down. The exact nature of his compromises will he discussed later

in this chapter.

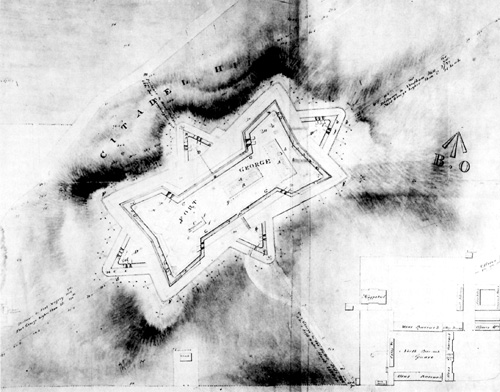

5 "Plan No 1" (1825). This was Nicolls's original plan for the Citadel.

In the course of construction, the eastern front was redesigned, the

north cavalier and the caponier were abandoned, the magazine was

demolished and new magazines and additional casemates were added.

Despite these changes, the west, north and south fronts as finally

constructed are virtually identical with the original design.

(Public Record Office, London.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

IV

Nicolls drew up his plans and estimates, which were duly dispatched

on 20 December 1825. "You will easily perceive," he wrote to Mann, "that

the trace has been formed more to answer the extent and nature of the

ground than according to any regular system of

fortification."16 It had indeed; compared to textbook plates,

the trace was peculiar. It resembled a stubby arrow feathered at both

ends. For this oddity Nicolls proposed to spend a total of

£115,999 16s. 3 3/4d.17 Despite its peculiarities,

General Mann could easily have discerned in Nicolls's plan echoes of

earlier proposals and suggestions for fortifying the hill, including at

least one of his own.

The title page of Nicolls's estimate reads: "General Estimate of

expense of reconstructing in masonry, altering and

adding to Fort George" (emphasis mine).18 This

insistence on the relationship between Nicolls's design and the third

Citadel (Straton's) is particularly appropriate. The two had much in

common. Both contained four bastions and were alike in

outline;19 both made use of cavaliers. Nicolls's ramparts

were at least as high as those of his predecessor, and were occasionally

higher,20 despite the fact that in his excavations of the

fort's interior, Nicolls had cut down the crest of the hill by as much

as 20 feet. There were divergences, most of them resulting from one

factor: Nicolls's use of permanent building materials. He was,

therefore, able to make use of elaborate fortification techniques which

had been denied Straton.

The greatest difference between Nicolls's and Straton's traces of the

fort, however, was in their respective conceptions of the difficult

northern and southern fronts. Nicolls considered Straton's trace

unacceptable; the fronts were "so short as not to admit regular

flanks."21 Both Fenwick and Arnold had proposed solutions for

this defect, but Nicolls discarded both men's ideas and selected a

method which Arnold had previously rejected, that of flanking from

reverse fire casemates in the counterscarp.

The individual elements of fortification which Nicolls used fell into

two classes: those which his predecessors had proposed and which had

never been built, and those which (so far as we know) Nicolls originated

himself. The casemates and caponier come under the former heading; the

counterscarp gallery, countermines and ravelins come under the

latter.

Casemates had found their way into both Fenwick's and Arnold's plans

in one way or another, but in neither plan had they been put to such a

variety of uses as in Nicolls's design.

In so small a work without casemated cover, troops may be shell'd

out immediately.

The smallness of the work also admits of but a weak diverging fire

being brought on the ground around it. By Casemated Cavaliers this fire

is greatly increased and the Troops have at all times a Barrack secure

from shells. — And for this reason as being the most exposed, I

have also placed a Casemated Defensible Guardhouse on each of the . . .

Ravelins, there not being a Covert Way.

The ditches of the Ravelins have been flanked by Casemates in the

Body of the place, — the fire from the interior outwards, when it

is to be procured, being preferable to that from the exterior

outward.22

In all, Nicolls proposed a total of 34 casemates including 16 single

storey casemates in pairs under the ramparts, 7 two-storey casemates in

each cavalier, and a casemated guardhouse in each ravelin. Of the total,

20 casemates (those in the ravelins and under the ramparts) were

intended primarily for defence; the remainder were to be bombproof

barracks.

The caponier was to serve two purposes; it was to be a flank defence

for the west ditch and a communication with the west ravelin. The idea

of using the caponier to defend the west ditch had first appeared in

Arnold's design for the northern and southern fronts, outlined in his

letter of November 1825. (See . . . we have nothing on Citadel

Hill but a heap of ruins ... above.)

V

Nicolls may have planned a counterscarp gallery and counter-mines

because it was impossible to form a covert way as a first line defence.

In any event, he seemed to consider them to be a logical outgrowth of

the four reverse-fire casemates.

[The north and south fronts] have . . . been flanked by casemates

of reverse fire from the Counterscarp which also serve as Galleries for

Mines, and I have included in the Estimate a Counterscarp Gallery around

the direct Galleries to run out 20 feet beyond them allowing for Mines

being exploded at that distance without injuring to [sic] the

Counterscarp, or that low Galleries may be made to branch out at

leisure.23

The counterscarp gallery was a relatively unusual feature. Ravelins,

on the other hand, were common in bastion fortifications, but none of

Nicolls's predecessors had proposed their use. Straton lacked the

wherewithal to build them properly, and ravelins on the northern and

southern fronts as he designed them would have made the fronts look

ludicrous. The spirit of Fenwick's design was such that ravelins would

have been entirely irrelevant. According to Arnold's plan, there would

have been insufficient room for them on the eastern and western fronts.

Considering the size of Nicolls's ravelins on those sides. Arnold may

very well have been right.

Arnold recommended, as we have seen, the occupation of a good deal of

ground on the northern and southern fronts, beyond the limits of

Straton's trace, to provide adequate flank defence and to take advantage

of the commanding nature of the ground. This second reason presumably

justifies Nicolls's occupation of much of the same ground with

ravelins.

Three of the ravelins, those on the north, west and south fronts,

were basically alike. In each of them, the guardhouse was placed in the

centre of the gorge and was surrounded by a shallow ditch which took up

most of the area beneath the ramparts in the ravelins' interior. The

only important differences among the three were, first, the size of each

(the northern and southern ravelins were identical and larger) and

second, the means of access. The north and south ravelins were to be

"entered from the ditch by wooden stops to be drawn up into the

Guardhouse"24 while on the western front there was to be a

casemated two-storey guardhouse, the lower storey of which was to

connect directly with the caponier.

The east ravelin connected to the body of the work by a bridge which

entered at the mid-point of the gorge. Another bridge, approached

through a passage under the ramparts on the right face, led to the

exterior. In the eastern ravelin, the guardhouse was shaped irregularly

and had no ditch. It was located on the left side of the gorge,

immediately adjacent to the ramparts.

The shape of the fort made its interior cramped: the distance from

curtain rampart to curtain rampart was less than 150 feet. It would seem

that the four bastions were intended to be hollow, although contemporary

plans vary on this point. The ramparts on the west side were somewhat

thicker than those on the east;25 this allowed more space in

the northern and southern ends.

What interior space there was in the northern end of the fort was

almost entirely taken up with the two identical cavaliers, one on a

north-south axis between the curtains, and the other on an east-west

axis fitting rather snugly between the bastions. Each consisted of seven

two-storey casemates surmounted by a masonry and earth parapet, a

terreplein, possibly of wood or earth (neither the plans nor the

contemporary documents are explicit on this point) and curbs and racers

for seven guns on traversing platforms. Both cavaliers were intended as

quarters; the northern one was to be "a convenient Barrack for 320 men"

and the eastern one "Officers Quarters for 4 Captains and eight

Subalterns."26

Certain peculiarities in the design of these buildings deserve

comment. For one thing, the only provision made for access from the

lower to the upper storeys of the casemates was by means of staircases

in a wooden verandah which was to run along the interior side of each

cavalier. As it was intended to remove the verandahs (to keep them from

being set on fire) during an attack, it is interesting to speculate how

Nicolls intended, in such a situation, to get men and ammunition to the

guns on the roof. Another odd detail was the arrangement of the chimneys

for the fireplaces in the casemates. The chimneys were to run through

the exterior wall and emerge flush with the masonry parapet on the roof.

Obviously Nicolls intended never to light fires during a

siege.27

Nicolls provided no detailed account of the armament proposed for the

work. It is likely that he had no more than an approximate idea of the

type and calibre of the ordnance to be mounted as he drafted his plans.

He did make allowances in his estimates for platforms and embrasures in

the appropriate places, as well as for traversing platforms in each of

the north and south ravelins — two in each face — as well as

four traversing platforms in the west ravelin and three in the east. He

planned one embrasure at each of the bastion and ravelin salients, and

seven on each of the cavalier roofs. The plan also shows two mortar

platforms in each of the western bastions.28 The 16 rampart

casemates were intended to mount guns. The total number of gun positions

would have been 63, a number which may be taken as an approximation of

the number of guns intended for the work.

The fort was provided with seven sally ports. One of them provided

access to the caponier. There were two in each curtain, and one in the

re-entrant angle of both northern and southern fronts, all leading to

the ditch. The two in the western curtain emerged opposite the

rudimentary place d'armes flanking the west ravelin; they therefore

provided access to the only defensive position proposed for the top of

the glacis.

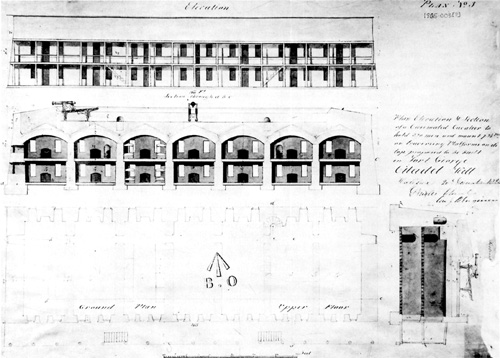

6 "Plan No 3" 1825. This, Colonel Nicoll's original design

for the cavalier, was much altered in the course of construction.

(Public Record Office, London.)

|

VI

Nicolls did not give a detailed account of the dimensions of the

works in his proposed fort at any point in either his estimate or his

covering letter. The estimate, in fact, gave only a cursory account of

the cost of each individual work, without detailed calculations of

materials, labour and workmanship involved. The only entries which come

close to accounting for the extra services necessary for construction on

the scale Nicolls proposed are as follows: a recommendation for the

purchase of 12 horses "for the service of the work;"29 one

entry for £385 for "scaffolding, wheeling, planks, etc.," and

another entry for £585 for "Repairs to tools, etc."30

Similarly, there were few references to building materials. The estimate

called for "granite quoins at the Salient angles of the shoulder

[sic] of the bastions," but did not specify the type or quality

of stone to be used in the remaining 99 per cent of the escarp

wall.31 The whole question of labour was dealt with in a

single paragraph.

The Estimate has been formed on the Principal of Workmanship being

performed 3/4 by Civil Artificers 1/4 military. . . . — But this

will vary materially according to the circumstances, as well as in

regard to the Military assistance to be had as what part of the

workmanship may be performed by contract; which I may offer my opinion,

as to works of Fortifications I consider not likely to be more

economical or the works to be equally well performed as by military

Artificers, supposing the principal part to belong to the Corps of Royal

Sappers and Miners; — as to stone, the principal part of the

material, I much doubt the Department obtaining it by contract as cheap

as by quarrying.32

This last sentence is the only reference to the manner of supplying

the raw materials, except for a recommendation that the necessary bricks

be sent from England as ballast, "as the Bricks here are of very

inferior quality."33

Nicolls's estimate was, therefore, somewhat less precisely worded

than one might expect. This made it easier for the colonel to conceal

the compromises he had made in formulating the design. There were two

major ones: the retention of the old powder magazine and the unusual

thinness of the escarps.

Nicolls retained the powder magazine he himself had built in 1812 for

use in the new Citadel. The magazine was a stone, bombproof building

with a capacity of 1,344 barrels of powder,34 located in the

new fort at the southern end of the eastern curtain. In his covering

letter, Nicolls mentioned it only once, to note that it could be

advantageously used in the new work.35 Nicolls's own section

drawings clearly showed that the floor of the old magazine was 10 feet

higher than the proposed level of the parade square of the new fort.

Moreover, the magazine roof was somewhat higher than the adjacent

ramparts.36 Nicolls mentioned neither fact in either his

covering letter or his estimate, and this omission seems to have gone

unremarked in London.

Nicolls's escarp sections were another, less obvious problem. It is

difficult to ascertain the dimensions of the escarps. In this, the

modern researcher is a good deal better off than the gentlemen in the

Fortifications department were at the time, since he, at least, has

access to the contract specifications of 1828-1829 and 1830. The

Fortifications department had no information whatsoever in Nicolls's

estimate and covering letter; their only guides were his section

drawings. These were contrived in such a way that, in almost all cases,

they showed the escarp where it was broken either by a sally port or by

the gate.37 This circumstance, obviously, made accurate

measurement of the escarp almost impossible. It also obscured the fact

the Nicolls's escarp sections were rather less substantial than the

fortifications textbooks permitted. A comparison between Nicolls's

escarps and Vauban's recommendations (see Table 2) shows that

Nicolls's escarps were, on the average, two feet thinner than they

should have been. The same comparison also reveals that Nicolls's

buttresses were up to three feet shorter than Vauban recommends, and did

not in all cases run up the whole height of the wall.38

|

| Table 2. Nicolls's Escarp Profiles compared to

Vauban's recommended Dimensions for Escarps of similar Size* (all

measurements are in feet) |

|

| Vauban

|

Nicolls

|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|

| Height of wall |

20 | 30 |

20 | 25 | 30 |

|

| Thickness (base) |

9 | 11 |

7 | 7 | 9 |

|

| Thickness (top) |

5 | 5 |

3 | 4 | 3 |

|

| Buttresses (length)† |

6 | 8 |

5 | 5 | 5 |

|

| Buttresses (width)§ |

4

to

2'8" | 5

to

3'4" |

— | 4 | — |

|

| Buttresses (height) |

20 | 30 |

15 | 25 | 24 |

|

*Columns 1 and 2 are derived from John Muller, A Treatise

containing the Elementary Part of Fortification . . . (Ottawa:

Museum Restoration Service reprint, 1968), p. 50; column 4 is derived

from PAC, MG12, WO55, Vol. 1558, part 7, p. 50; Columns 3 and 5 are

derived from NHPSB Plan 02-1825-12-2. These last figures are less

accurate than the others.

†Measured at right angles to escarp wall.

§Greater figure is width next to wall.

VII

It is difficult to assess Colonel Nicolls's design for the Citadel.

On the one hand, it is a competent piece of work, more sophisticated

than previous plans and better adapted to the site than any of them,

with the possible exception of Arnold's. On the other hand, Captain

Fenwick's towers would have been cheaper and strategically more suitable

for the hill. Nicolls's fort is admirable enough in itself, but its

utility can be questioned. It is doubtful whether there was any purpose

for the fort other than the one Nicolls himself suggested; to show the

flag.

The suitability of the work, however, is not as important to its

subsequent history as the adequacy of the specifications for its

components set forth in Nicolls's estimate. Those were demonstrably

insufficient to meet the demands of the local climate and soil

conditions. The work had barely gotten under way when their

insufficiency became embarrassingly obvious. Within four years of the

beginning of construction it was apparent that major alterations (and

more money) were necessary if the work was to be properly finished. By a

misguided but entirely characteristic attempt to please his superiors,

Nicolls not only put his own competence as an engineer seriously in

question but also delayed the completion of the Citadel by almost a

quarter of a century.

|