Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 17

The Halifax Citadel, 1825-60: A Narrative and Structural History

by John Joseph Greenough

". . . I now think I made a little too free with the Climate . . ."

I

In the hierarchy of the Ordnance in London, the office most directly

concerned with the Halifax Citadel was that of the Inspector General of

Fortifications. Like so much else about the Ordnance, the title was

something of a misnomer. The Inspector General in fact supervised all

the activities of the three Ordnance corps — the Corps of Royal

Engineers, the Royal Regiment of Artillery, and the Corps of Sappers and

Miners. Fortification was only one of the Inspector General's

responsibilities. He could not make major administrative decisions

(i.e., those involving policy or money or both). These were referred,

through the Secretary of the Ordnance, to the Master General and

Honourable Board of His Majesty's Ordnance. Theoretically the process

was simple enough; the secretary was to lay the matter, whatever it was,

before the Master General and board and the latter two were to render a

decision. But in reality the process was somewhat different. Despite

the impossing formulation, the Master General (invariably a soldier) and

the civilian board rarely had much to do with each other, and neither,

in most cases, actually made decisions. The important figure in most

transactions between the Inspector General and the board was an

intermediary, the secretary (properly, the Secretary to the Board of

Ordnance). This gentleman was the permanent departmental

under-secretary, roughly the equivalent of a modern deputy minister, and

his recommendations were usually accepted.

An example will serve to illustrate the workings of the department.

The Commanding Royal Engineer at a station would address himself

directly to the Inspector General. If a decision was necessary, the

Inspector General would write to the secretary, enclosing the engineer's

letter and any other documents he considered relevant, giving his

opinion and requesting a decision. The secretary would then go through

the motions of presenting the case to the Master General and board. In

some instances, if the matter was sufficiently important, the Master

General would either write a memorandum on the subject or would minute

the margin of the engineer's letter. The secretary would then compose a

short letter rendering the decision and return it, along with the

original correspondence and any marginal annotations acquired since, to

the Inspector General, who would then refer it to one of his deputies

for transmission back to the station. The whole process could

take only a few days. More commonly it took months and occasionally

years.

In the summer of 1828, the key positions in the Ordnance were held as

follows:

Inspector General of Fortifications: General Gother Mann

Deputy Inspector General: Major General Sir Alexander Bryce

Secretary to the Board of Ordnance: Richard Byham

Brigade Major, Corps of Royal Engineers; Lieutenant General Charles Grene Ellicombe

The Master General, Lord Boresford, had held office for only a few

months, and Byham only since 1827. Mann, who had been an engineer for 65

years, Inspector General for 17, and a full general for 7, was, for the

moment, the most powerful man in the Ordnance.1

II

The Inspector General's office acknowledged receipt of Nicolls's

Citadel scheme on 21 March 1826.2 Nothing further was heard

on the subject for more than two years. Mann contented himself with

referring the plans to Sir James Carmichael Smyth for comment, and,

when the latter pronounced himself satisfied,3 allowed the

subject to drop. It was not until parliamentary approval of the

necessary funds was imminent that Mann formally submitted the scheme to

the Master General and board for approval.4 His accompanying

letter was terse. "I concur with the opinion of Sir James Carmichael

Smyth of its [the plan's] fitness for the situation and that the

estimated expense, £115,999 appears moderate and, if the measure

be adopted, one of great economy." Despite the fact that it was already

almost July, he proposed to ask for £15,000 for construction in

the current year.

The Master General was in complete agreement. His only contribution

was a comment on building methods appropriate to North America. "No more

length of work should be laid down than could be completed to the top

during the season as covering it for the winter frost occupies much time

and is very expensive."5 In fact, no one connected with the

higher reaches of the Ordnance seemed to be too concerned about the

project. The following day, 17 July 1828, Byham dispatched the letter of

approval of the project to the Inspector General.6

Before sending the letter on to Halifax, Bryce appended a couple of

suggestions as to how the scheme could be improved. The most important

one concerned the cavaliers.

[Colonel Nicolls] is requested to consider whether it might not be

advisable to construct the casemated cavaliers in four distinct

positions . . . placing one in each Bastion across the Capitals . .

. [this] would . . . have the advantage of furnishing a powerful

Blockhouse or retrenchment in each Bastion without lessening in any

degree the accommodation for Troops & Stores.7

This was London's only quibble with the proposals, and it was added,

almost as an afterthought, on the same day that Colonel Ellicombe drew

up the covering letter for transmission to Nicolls. Approval had taken

only 36 days. Never again would a major decision regarding the Citadel

be made so quickly.

III

For almost three years, the Citadel project had been in limbo. Now

that official approval had finally been granted, a whole host of

difficulties had to be dealt with. For the remainder of the 1828 working

season, Nicolls confined himself to doing some preliminary excavation

and addressed himself to the formidable task of finding the materials

and workmen necessary to begin building in the following year. In

October he sent a progress report to London.

I have made a commencement in excavating the ditch of the West

Ravelin which being the lowest part of the West front (the most

important) it is necessary should be first excavated in order to afford

free water course for what would otherwise be pent up in the

ditch.8

He detailed what he proposed to construct in the following year: the

west ravelin counterscarp and part of the west escarp. The first was to

be built by soldiers (Royal Sappers and Minoes and artificers from the

line regiments) and the second by civilian contract.

Nicolls anticipated trouble in procuring enough skilled workmen, so

much so that he recommended hiring 20 civilian masons in England and

shipping them to Halifax for the working season. He also noted that

there were only two brick-makers in Halifax and that local supplies

were, in consequence, both insufficient and excessively expensive. He

therefore recommended that 100,000 bricks be sent out from England. He

concluded his report by agreeing with the Master General's directive

about construction methods, but noted that an exception would have to be

made in the case of the cavaliers, since "it would not be advisable to

construct the whole in one season. . . [The] arch part, which must

thereby be done late in the season would never become thoroughly dry, or

might even yet be affected by the frost." He proposed erecting the

cavalier up to the springing of the arches in one season and turning the

arches in the following spring. He did not think that this would be

either dangerous or expensive, since the standing walls could be

protected for the winter by the scaffolding.

In a second letter, Nicolls dealt with Bryce's suggested alterations

to the cavalier. Those he rejected. He considered the northern and

western cavaliers to be necessary, the one to cover Camp Hill and the

other to enfilade Needham Hill; their function would be impaired by

placing them across the capitals of the bastions. He did, however, admit

that a third cavalier facing Fort Massey Hill to the south might be

desirable, and suggested splitting the north cavalier, leaving four of

its seven arches in the original location and removing the other three

to the south end of the fort. He concluded,

this division might keep the defence more in equilibrio, but will

cause some increase of expense, requiring 2 additional abutments 8

ft. thick — instead of one centre pier of 4. . .

.

By allowing the [west] Cavalier B to remain on its present

site and dividing [the north cavalier] A into two [north]

A, & [south] K, each flanking [the west] B and

being flanked by it, it would only be necessary in time of war and

alarm, to build up and loop hole their lower doors and windows to form a

most powerful Retrenchment within Fort George; which Work is on too

small a scale to render a Retrenchment in each Bastion

necessary.

The last paragraph of the letter was pure Nicolls;

In offering these explanations, it is with much deference I differ

in opinion with Sir Alexander Bryce, even though that difference is in

the local, in the principles recommended in his suggestions I entirely

concur.9

In fact, Bryce's suggestion was ill-suited to the realities of the

site, and Nicolls had made a perfectly adequate rebuttal of it. Nicolls

conceived of the cavaliers as gun platforms directed at specific targets

and placed them accordingly. Bryce's conception of them as redoubts was

more than a little ridiculous, given the situation. Examples of a

garrison continuing to hold out when the enemy was busily engaged in

setting up gun positions in the interior of the nearly captured

fortress were rare, especially so in the case of a work as comparatively

tiny as the Citadel. Nevertheless, Nicolls felt obliged to whitewash his

difference of opinion, first by subscribing to the redoubt theory, and

second by denying that any such difference existed.

As it happened, Bryce and Mann never noticed the difference. What did

strike them forcibly was that Nicolls had used that ominous phrase,

"increase of expense." A terse reply was drafted within days of the

arrival of Nicolls's letter. General Mann agreed with Nicolls's proposal

and requested an estimate. "provided it should not exceed the expense

originally estimated."10 Nicolls was given no indication of

how this could be done. Once again, in an attempt to please his

superiors, he had talked himself into a corner.

7 Ground plan of the Citadel in October 1828, Colonel Nicoll's original

design. It was drawn at the end of the first working season and shows

the progress of the work.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

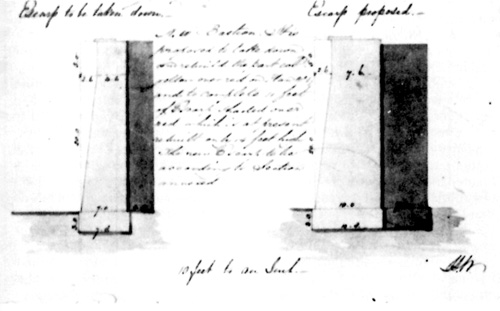

8 "Escarp to be taken down" and "Escarp proposed," 1834. The escarp to

be taken down was built to the specifications of the 1828 contracts. The

escarp proposed was the final variation on the standard escarp used to

replace earlier failures.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

IV

Nicolls spent the remainder of the winter of 1828-29 attempting

to solve the problems outlined in his letter to Mann. His task was made

easier by the fact that his request for stores and civilian masons from

England was quickly granted (although the wording of the letter left in

doubt the number of masons to be hired),11 but by this time

another difficulty had arisen. Up to that point the Engineer department

in Halifax had apparently never owned a quarry. In November, Nicolls

wrote to Mann outlining the steps he had taken to get possession of a

suitable site in Purcell Cove. The property had been escheated to the

crown in the preceding year. Nicolls needed money to develop it —

specifically £47 10s. 10-1 /4d. for a wharf and roads, and he now

requested that London approve the expenditure.12

While he waited for a reply, Nicolls turned to the business of

finding a civilian contractor for the escarp wall. Early in November

tenders had been called.13 It had been specified that no

builder could contract for less than 300 feet, that the work was subject

to the inspection of the Engineer department, and that the contractor

was to supply his own scaffolding and materials, except for the stone

itself, which was to be ironstone from the department's quarry. On 6

December, Mr. William Flinn contracted to build 400 feet of escarp on

the terms specified at 12s. 9d. per perch.14 (A perch of

masonry was 24.75 cubic feet.) A bond of £1,000 sterling was

posted by Messrs. Barron and Trider, guaranteeing performance of the

contract. A few days later, a second contract was let to Mr. Peter Hays.

The second contract was identical except that, for some reason, Hays got

a better deal 13s. 8-1/2d. per perch.15 The wording of the

contracts was vague enough to give rise to questions about their

legality some years later (see below), but for the moment

Nicolls's immediate problems were solved.

There remained the question of the labour force. A large proportion

of the force was drawn from the garrison regiments, and Nicolls depended

on the good will of the general officer commanding to ensure an adequate

supply of workmen from this source. Throughout the winter, Nicolls had

supposed that his major problem would be to find enough civilian

labourers. In early May he got a nasty jolt. His brother officers were

less than enthusiastic about cooperating. A routine request for an

increase in the Citadel working party from 100 to 150 regular soldiers

touched off a row when Lieutenant Colonel Harris, the deputy adjutant

general, revealed that Lieutenant General Maitland, commanding the

forces in Nova Scotia, was unhappy about the number of men engaged in

work parties.

It appears ... that from the number of Soldiers employed in the

Public Departments either as Workmen or on Fatigue, the daily Casualties

and Garrison guards, the united strength of the three Regiments would

amount to no more than 428 Privates, for all purposes of drill and other

Military instruction during the Summer.16

General Maitland disliked having an insufficient number of soldiers

to drill and, as a result, decided to cancel all working parties on

Wednesdays and Saturdays for the remainder of the summer.

This bombshell came on the very day when Nicolls had written a letter

to one of the regimental colonels complaining that his men habitually

arrived late and unattended by an officer, the officer "not arriving

until some time afterwards."17 Maitland's decision roused

Nicolls to one of his few recorded examples of tactlessness. He replied

to Harris, comparing the new attitude unfavourably with the cooperation

he had received from Sir James Kempt (Maitland's predecessor),

complaining that work would be slowed up under the new policy and

requesting that at least a token force of necessary artificers be

exempted from the ban.18 The next day Nicolls repented of his

rashness and wrote a more conciliatory epistle,19 but by then

it was too late. Maitland refused to rescind his order and it stood for

the rest of the summer, although the general did relent to the extent of

taking 10 men from the Georges Island work party and putting them to

work on the Citadel at the end of May.20

On 24 June a company of the Royal Sappers and Miners and members of

the Royal Staff Corps arrived.21 If Nicolls expected them to

alleviate the labour situation to any degree, he was mistaken. Less than

two months later he was complaining bitterly about their abilities.

I by no means receive the assistance I expected from the 18th

Company of Royal Sappers & Miners, lately sent to this Place. —

it is generally deficient in good Workmen, and particularly so in

Masons and Bricklayers; the non-Commissioned officers are but of

comparatively little service on the works, the two Serjeants being

Collar Makers, and the rest not particularly skilful in their

trades.22

He suggested that the vacant positions in the company be filled with

skilled masons and bricklayers; otherwise it would be necessary to hire

a civilian foreman "at additional expense." In the final paragraph of

the letter, Nicolls had comments to make on the quality of the garrison

soldiers as labourers.

The Staff Corps possesses some very good artificers, but I have

kept them as much by themselves as the Service would admit, as it seems

natural that Soldiers paid whether they work or not, and others paid

according to their diligence and attention [i.e., the Staff Corps]

are not likely to mingle well together.

The soldiers who were "paid whether they worked or not" caused at

least one incident with a civilian contractor in the course of the

summer. Mr. Patrick Kelly, a carter, complained that he was being

harassed by both the foreman and the working parties. The former was

forcing him to overload his cart in violation of his contract. He

claimed that one of the latter had threatened that

if they did not get rum from me they would break my trucks

in loading and this they expressed in the presence of the Overseer of

Labourers, whom I called upon to prevent such conduct, he made light of

my entreaties and said he could do nothing about

it.23

Unfortunately for Mr. Kelly, his complaint fell on deaf ears. By the

time it was written, Nicolls was convinced that the contractors were at

least as much trouble as the troops, and was not at all well-disposed

toward them.

In fact, by the end of the summer, Nicolls's relationship with his

civilian contractors was beginning to resemble a farce with paranoiac

overtones. The colonel had become convinced that most of the contractors

were cheating, and laboured mightily to prove it. He had the trucks

weighed, the hogsheads measured and the stones counted. Unfortunately

for his peace of mind, every time he thought he had proved his case, he

found himself thwarted by the deputy commissary general, George Damerum.

It was Damerum's business to negotiate contracts and oversee the

contractors, and it was his increasingly unpleasant task to demonstrate

to Nicolls's satisfaction that most of the illegalities were, in fact,

nothing more than misunderstandings.

As an example (admittedly an extreme one), take the case of William

Roach, the contractor for lime. Nicolls, on measuring one of Roach's

hogsheads, found it to contain less than he thought it

should.24 The difficulty lay in the fact that the definition

of a hogshead, as set forth in the statutes of Nova Scotia, had

inadvertently been carried over into the contract. According to the Nova

Scotian government, a hogshead contained "8 Winchester bushels or 96

gallons."25 Unfortunately the two measurements were not the

same; 96 gallons was somewhat larger than 8 Winchester bushels. Roach

insisted on the bushels,26 while Nicolls held out for the

gallons. No amount of persuasion from Damerum and ultimately

from the general officer commanding could convince Nicolls that Roach

in fact had a case. The correspondence on the subject dragged on into

November and was finally settled by compromise only after Nicolls

threatened to take the case all the way to the Treasury.

When the working season finally came to an end in

mid-November27 everyone was vastly relieved. While all

concerned recognized that it had been an exceptionally bad year, they

hoped that this only reflected the inevitable difficulties arising from

the commencement of a major work. The next season, 1830, would see

better results.

V

One reflection of the season's difficulties was the financial balance

sheet. Parliament had granted £15,000 in 1828 and a further

£15,000 in 1829,28 for a total of £30,000. Of

this only £10,595 had been spent.29 Despite this,

neither Nicolls nor London was unduly alarmed. In fact, Nicolls

requested and got £20,456 18s. 1d. on the Citadel account in the

annual estimate for 1830-31, the largest amount ever granted in a

single year for the project.30

One reason for optimism was that the two masonry contractors had

managed to build their allotted portions of escarp within the required

time. The system having worked so well, Nicolls saw no reason to change

it. On 15 October Nicolls issued a specification for 1,000 feet of

escarp; the wording of the specification was, in most respects,

identical to that of the previous year.31 The first contract

was let to Mr. John Metzler on 8 December. It was for 500 feet of escarp

at the rate of 12s. 7d. per perch.32 The contract for the

other 500 feet went to Peter Hays, who once again managed to get a

better rate — 13s. 7-1 /2d. per perch.33

The working season opened early in May with the usual wrangle with

Harris about the number of men available for the working

party.34 Once work had begun, however, things went relatively

smoothly. There were the usual problems with the labour force, but not

to the same extent as in the previous summer. Similarly there were few

open disputes about contracting. Nicolls contented himself with a

protest to London over the wording of Damerum's contracts for truckage

and supply (the building contracts had been largely the colonel's own

doing). Damerum's contracts were, Nicolls contended, imperfectly worded

and were open to criticism on that score.35 Viewed in the

light of subsequent developments, this was an ironic complaint.

By the end of the working season, much had been accomplished. A good

index of the progress was the rate of expenditure. The work had cost

£18,375 in 1830,36 almost twice as much as had been

spent in the two previous years put together. While it was true that

neither of the two contractors quite completed the required 500 feet of

escarp. Nicolls and the Engineer department were in a forgiving mood. On

4 November Peter Hays signed his third consecutive contract with the

department, agreeing to complete the portion of the work left unfinished

in 1830 and to build another 320 feet of escarp the next year, all for

the price of 13s. 7-1 /2d. a perch.37 Four days later Mr.

Metzler signed a similar contract; he agreed to complete his portion of

the unfinished wall and to build an additional 186 feet. He was to

receive the same rate as Hays.38 Both contracts were awarded

on Nicolls's recommendation, without further tenders being

called.39

The respective officers (Nicolls and other Ordnance staff) defended

their actions on the grounds of continuity. There was no point in

calling for new tenders, they argued; work by an experienced builder

with knowledge of the project was safer and in the long run more

economical than work by a new contractor.40 Colonel Nicolls

pronounced himself completely satisfied with the work done by Hays and

Metzler.41 The reports of both the respective officers and of

Nicolls himself made special mention of the "well-shaped large stones"

which Mr. Hays used.

Then, on 9 December, 50 feet of escarp in the southwest bastion, which

had been built by Flinn in 1829, suddenly collapsed.42 This

was bad but not disastrous; Flinn was not, after all, one of the

favourite contractors. If it could be proved that the collapse was the

result of faulty workmanship, Nicholls had nothing to fear. He promptly

submitted the documents relevant to the case to S. G. W. Archibald, the

solicitor general of the province, to see whether legal action could be

taken, Archibald replied on Christmas Eve. He was not encouraging.

I have carefully examined enclosed to me . . . and I am of the

opinion under the Contract and the manner in which it was agreed that it

should be executed that there would be great difficulty in this case of

compelling the Contractor either to rebuild the wall . . . or to answer

in damages for such rebuilding.43

Even if Archibald had been more optimistic, it would have been little

comfort for Nicolls. Two days earlier 70 feet of Hays's wall in the

northwest bastion had also collapsed.44 It must have been a

very gloomy Christmas for the colonel.

It was not until 28 January that Nicolls addressed himself to the

odious task of conveying the bad news to London.45 The

failure of Flinn's work was the easiest to explain; it had bulged as

early as November 1829, and in consequence Nicolls had refused to give

Flinn another contract. The work had been clearly defective from the

start, although the legal situation was such that criminal prosecution

was impossible. Hays's work was another matter. Nicolls was at a loss to

suggest an explanation, though he did suggest that the stones used had

perhaps been too small. Then, too, the climate was so damp that the

mortar had never set properly. He noted the improvements

which had been made in 1830 in terms of the thickness of the wall and

the quality of the stone, and stated that he entertained no fears about

the durability of the work built in that year. To strengthen subsequent

building still further, he recommended thickening the escarp sections

and using cement to point the faces. He noted that he had used

contractors for reasons of economy and speed, since the reserves of

military manpower were insufficient to build at so fast a rate. He

concluded,

It is with much regret I have to bring a Report of the foregoing

nature before you; and beg to assure you that I shall use my best

endeavours to profit by the experience gained in the last two Years, and

adopt circumstances as much as possible to this Climate, so very

unfavourable for building massive walls to retain moistened earth. . .

.

I entertain hopes that the Hill will still be completed for the

sum originally estimated.

Unfortunately the memoranda and letters sent in reply to this letter

are missing. One suspects that they made unpleasant reading. We do know

that the Board of Ordnance was at the point of approving a grant of

£14,931 on the Citadel account for the 1831-32 season when

Nicolls's letter arrived, and that the amount was cut to £4,989,

ostensibly because of the unexpended balances.46 We can infer

from Nicolls's reply to the missing letters that he was instructed to

stop using contract masons after the expiration of the current (1831)

contracts. We also know that Colonel Ellicombe addressed a personal

letter to Nicolls, and we have Nicolls's reply. It is resigned and

almost whimsical in tone.

Dear Ellicombe

I view your note of 2d March as kindly intended — and

therefore thank you for it — However, I entertain little

apprehension for any thing built at Fort George since 1829, in which

year I now think I made a little too free with the Climate — but .

. . I have written officially and fully on the subject . . . and there

is little pleasure in repetition of this nature. . . .

We are hard at work at the Hill — but we get no

Military artisans or Labourers, except Sappers and Staff Corps either

for it or the Barrack service, on Wednesdays & Saturdays— This

helps to increase the expense considerably, perhaps you could inform me

whether this is according to the spirit of the times, and general custom

where there are considerable Works carrying on.47

Nicolls's official response took the form of a letter and two

estimates for the work which he had intended to have Messrs. Hays and

Metzler do in the 1831 working season. The first was for 372 foot of

north ravelin escarp; the second for 186 feet of curtain. The new

estimates, which took into account both increased dimensions and the use

of military labour, exceeded the old by a total of

£957.48 The plans were rejected. Fanshawe (the new

brigade major) wrote on 29 June,

Sir Alexander desires me to say that he by no means feels

confident with a climate such as that of Halifax that the revetments

erected in 1830 are sufficient, and further that he cannot sanction the

construction of revetments at Halifax of a less mean thickness than that

used by Vauban, whose dimensions have now the advantage of long

experience over any calculations that rests [sic] in some degree

on theoretical data.49

Despite the uncertainty about the future, the working season

progressed as efficiently in 1831 as it had the proceeding summer. In

fact the department managed to spend £1,000 more in the course of

1831 than it had in 1830.50 But it was clear by the end of

the summer that some sort of settled policy on escarp sections was

necessary before the work could progress much further. It was also clear

that London was no longer disposed to listen to Nicolls, and it came as

no surprise when he was transferred to Quebec.

Nicolls made one last gesture. On the plan accompanying the progress

report dispatched on 3 September, he proposed a drastic alteration to

the eastern front — the abandonment of the ravelin and the

substitution of a redan. His explanation of the proposal was brief. It

would, he said, afford greater interior space and improve external fire.

It provided the ditch with flanking fire "as good or better than that

done away with." Finally the cost would be about the same as that of the

original proposal.51

London's reply was equally brief and requested plans and a detailed

estimate.52 It arrived on the same boat as Colonel Nicolls's

successor.

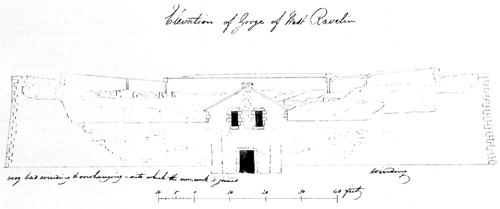

9 "Elevation of Gorge of West Ravelin," 1832. The failed ravelin as it

appeared to Colonel Boteler.

(Public Record Office, London.)

|

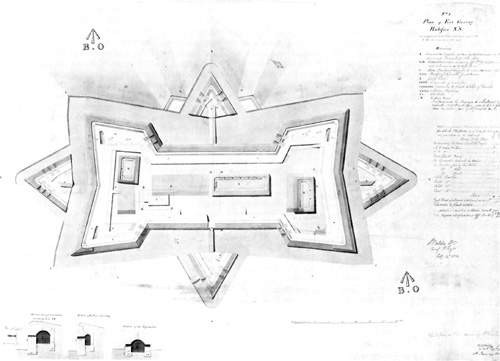

10 "Plan of Fort George," 1832. This is probably the best large-scale

plan of the Citadel in its original form, and was drawn to accompany

Colonel Boteler's letter of 14 January 1832. Appended to this version

is a list detailing the state of the work in January 1833.

(Public Record Office, London.)

|

|