|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 17

The Halifax Citadel, 1825-60: A Narrative and Structural History

by John Joseph Greenough

Truth and Consequences

I

Lieutenant Colonel Richard Boteler assumed Nicolls's command on 29

October 1831.1 It must have been plain to him from the start

that he had inherited a potentially dangerous and disturbing situation.

We can, from his later letters, picture him in his first months on the

station, picking his way around the rubble of the partly built Citadel,

looking in dismay at the breaches in the newly built walls, at the new

west ravelin, already twisted and misshapen,2 at the old

magazine, tottering on its island of mud in the middle of the partly

excavated parade square. Boteler asked questions of his subordinates;

there were few answers. Colonel Nicolls could tell him more, but the

colonel was already in Quebec City, thankful, no doubt, that the mess in

Halifax had passed into other hands.

Finally, in January 1832, the Fortifications department dispatched

copies of Nicolls's original estimates and later correspondence to the

new Commanding Royal Engineer, and informed him in a brief note that,

with respect to the revetments, the Inspector General could not

"sanction work of an inferior or insufficient description, nor a

substance of masonry less than was used by Vauban." The department also

asked for Boteler's opinion.3 The controversy which was to

swirl about Boteler and his successors had begun.

Boteler replied promptly, dispatching two letters and two expense

statements to London on 14 February. The first of those letters, a

summary of the state of affairs as he found them, was a long litany of

woe and confusion.4 The very shape of the fort was in

question. Was Nicolls's plan for a redan on the east front to be

adopted? Where were Nicolls's plans for drains for the place? Was it

intended to retain the old magazine? If it was, he begged to inform

General Pilkington that it held only 1,344 barrels of powder and was

"now standing on ground 10-1/2 feet above the level of the interior of

the fort." Was there any intention to provide barrack accommodation

beyond that in the three cavaliers? If not, he suggested that

the south Cavalier should be of the same dimensions as the north

and that both should be constructed with a central corridor and a

basement storey for servants. These buildings with the addition

hereafter of another cavalier similar to that already built as a

soldiers barracks, would contain accommodation for a regiment on the

present scale.

As to the work already begun, he did not consider it advisable to

continue with the west ravelin, since it was already twisted. He did not

think that the gorge would bear being carried up to full height. He had

similar reservations about the escarps; the one on the left face was

already bulging. He noted that the sum included in the 1832 estimate for

repairing the breach in the southwest bastion would only rebuild the

right face, and there was no money for repairing the breach in the

northwest bastion. In any event, he doubted the value of piecemeal

repairs to the old work; as places were repaired, others might "not

prove to be sufficiently good." He advised either waiting to see if the

masonry would stand or tearing it all down and rebuilding.

With all those difficulties it was not an easy task to find work

which could be undertaken. Boteler recommended continuing work on

the counterscarp and gallery opposite the northwest bastion, despite the

inconvenience of rubble spilling from the breach in the opposite escarp,

since this was necessary in order to keep the masons busy.

Boteler enclosed a balance sheet detailing the amounts remaining

unexpended of the parliamentary grants for the preceding three

years.5 The balance showed that most of the money had been

spent. Of the remainder, however, some could only be spent after the

problems raised in his letter had been satisfactorily resolved. This

list of problems, with Boteler's comments, is worth examining in

detail.

There was £2,277 6s. 9-1 /2d. left from the 1829 estimate on

the cavalier account. By Boteler's reckoning, all that remained to be

done was to sod the roof, shingle the verandah and lay the lower floor.

The cavalier was one of the few areas in which Boteler expected no

problems. There was £188 0s. 3-3/4d. left from the 1829 estimate

for four granite gun platforms. These belonged to the ramparts on the

west front and could not be placed because of the condition of the

walls. Another £145 11s. 0d. for the curbs at the salient angles

could not be used for the same reason. The sum of £1,562 14s.

8-3/4d. left on the 1830 account for the casemates of reverse fire could

be used, though Boteler doubted the wisdom of proceeding with the work.

The £139 11s. 3d. for retaining walls, £40 0s. 8d. for curbs

and £5 9s. 4-1/4d. for granite platforms, all for the west

ravelin, could not be spent because of the danger of the ravelin

collapsing. The remaining funds, mostly for excavation, could be

used.

When Boteler's letter arrived in London, the engineer officers were

astounded. Four cavaliers! Admission of the utter failure of previous

work! An inadequate and improperly placed magazine! No plans for

drainage! Whatever had happened? Who was to blame? Most important to

all, what was all this going to do to the estimates? Would they have to

go to Parliament again for money? The London staff had changed since

1828. Mann was dead; Wellington was loading the fight against the Reform

Bill in the House of Lords. In their places were Sir Alexander Bryce and

Sir James Kempt. It was Bryce who received the bad news first, and his

immediate, instinctive reaction was to try to preserve economy.

Under all the circumstances, it will in my opinion be advisable

that Lt Colonel Boteler be instructed to confine the operations at the

commencement of the Working Season, to the Excavation. Counterscarp and

Ravelin of the North Front, and that he should report how, in his

opinion, the objects proposed in the original Estimate can be best

attained without increasing the Expense already stated to

Parliament.6

Bryce agreed with Boteler that it was unwise to undertake piecemeal

repairs, and that it was necessary to wait and see how the work already

completed would stand up over several winters. He suggested that

casemating be substituted for cavalier construction. He had no firm

opinions about Colonel Nicolls's proposed redan.

It was left to Kempt, in a pencilled marginal note on Bryce's letter,

to assign blame for the situation and to speculate about the

solution.

I am exceedingly pained [?] to observe, by Lt. Col Boteler

[sic] Report, that the greater part, if not the whole of the

Revetments of 1829 Erected under the direction of Colonel Nicolls must

eventually be Rebuilt! — and I am pained [?] that an Officer of his

Standing and Character in the Corps Should have Committed such Serious

Errors as he must have done in the Plans & Estimates

Submitted by him for the Citadel of Halifax — particularly in

regard to the Strength and Solidity of the Several Revetments —

This is the more unpardonable Seeing that Colonel Nicolls had Several

years Experience of the Climate of N. America and ought to have been

fully aware of the strength [?] of Masonry absolutely necessary to

resist its Severity — indeed, I cannot but Consider what has

occurred to be highly discreditable to the Department. —

Nor Can I entirely acquit the Inspector General of Fortifications

from all blame on this occasion, — for altho the Executive [?]

Office is held responsible (and very properly so) for the Correction [?]

of his Professional [?] Plans & Calculations, yet the Master General

looks to the Inspector Genl of Fortifications for a Careful [?]

revision of all Such Papers — in the Case of every Work

Undertaken by the Department — and more especially When one of so

Much Magnitude and importance as the Citadel of Halifax — requiring

a great expenditure of the Public Money was in contemplation. . .

.

Seeing that the Revetments are imperfectly Constructed, it is a

great object certainly to relieve them from the pressure of a Solid

Rampart, and Casemating the North and South Fronts as proposed by Sir A.

Bryce in lieu of the two detached Casemated Cavaliers will I have no

doubt effect that object . . . but I can give no final decision on this

Point until I see Lt. Colonel Boteler [sic] further

Report.

J[ames] K[empt]7

II

One wonders what Colonel Boteler thought as the winter of 1832 wore

on. He had expressed his reservations about the Citadel project in

strong language and had implicitly criticized his predecessor. What

would London do? He got his answer in late May, and it was not

reassuring. The Fortifications department, terrified by the prospect of

asking Parliament for more money, demanded both results and economy

— demands which Boteler knew perfectly well were inherently

incompatible. He was to "complete the work in an efficient manner,

without increasing the amount of the original estimate or diminishing

the projected casemate accommodation, and preserving if possible the

Revetments of 1830, and 1831 which appear not yet to have proved

defective."8 He was to report on Colonel Nicolls's proposed

redan, which, Sir Alexander devoutly hoped, would "diminish the original

Estimate of expense, and be a desirable alteration." The counterscarp

gallery and mines on the east and south fronts were to be abandoned and

the repair of the defective escarps was to be postponed until it was

possible to find out whether they could be relied on. While Sir

Alexander was "by no means disposed to sanction the hazard of a

diminished revetment," he did wish, if possible, to "save those erected

in 1830 and 1831," and Boteler was to do this, if necessary, by

casemating. Finally the colonel was to report on the advisability of

constructing "additional Magazine accommodation under the Ramparts in

situations capable of thorough ventilation."

Fanshawe's private letter, which arrived with the same packet, was a

little more explicit about some points. Sir Alexander, Fanshawe

emphasized, was adamant about one thing; the revetments already built

were to be preserved at all costs. Where it was impossible to relieve

the pressure on the revetments by casemating, perhaps "additional

buttresses, arches of discharge, or . . . dry walls in the rear" would

serve as well. If it were absolutely necessary to rebuild failures, a

special account of the sums expended was to be kept.9

The spirit of those two letters, with their enclosed comments from

Bryce, was obvious, Boteler was

being asked to work a miracle in order to preserve the department's

honour. While we know that the Master General himself had agreed with

Boteler's implicit criticism of Nicolls, no word of Kempt's approbation

had seeped back to Halifax. Instead, the colonel got a curt injunction

in Fanshawe's letter against making comments which might "excite

controversial feelings." Boteler was to work wonders and he was not to

rock the boat. After all, as Kempt's memorandum made clear, any

criticism of Nicolls extended beyond him to the Inspector General's

office itself, and Bryce had been Mann's deputy.

The Inspector General was sufficiently upset about Nicolls's

performance to send him a copy of Boteler's letter of 14 February for

comment. On 21 July Nicolls, writing from Quebec City, resolutely passed

the buck back to the Ordnance.10 While it was true, he

admitted, that he had never framed an estimate for the drains, he

had shown them on his plan. Access to the ravelins through the

ditch was considered sufficient at other posts — Portsmouth, for

example. While the barrack accommodation was insufficient for the

garrison now proposed, it had been adequate for the number of men which

Carmichael Smyth had originally required. As for the magazine, Nicolls

wrote. "I believe there will be only a few spots outside Fort George

from whence the ridge of the roof of this Magazine maybe seen; when the

parapets [?] are complete; on this account no provision is made

for another." This last was the weakest point in Nicolls's case (should

the ridge of a magazine roof be visible from any point outside a

fort?) but on the whole the colonel acquitted himself well. Nicolls,

always the devious, ingratiating politician, succeeded in drawing

attention to the fact that his original design had been faithful to the

intentions of his superiors and had been approved by them. After he

scored this point, all attempts to assign blame for the Citadel debacle

temporarily ceased.

Nicolls's counter-attack was not forwarded to Halifax until

September,11 but long before this Boteler had taken steps to

protect himself in the event of the failure of his direct assault of 14

February. His position was, after all, unenviable. If he could not

convince London that the situation was indeed serious and that expensive

changes were necessary to complete the fortress properly, he would fail.

His professional reputation was at stake. Shortly after he launched his

direct assault, he changed to a different tack. The station records were

sketchy; twelve plans, seven of them from before 1826,12 and

a few dozen letters. If London could not be made to see the gravity of

the situation by direct means, perhaps a persistent series of inquiries

on points of detail would serve. By the end of the year, the Ordnance

had received more letters from Boteler on the subject of the Halifax

Citadel than it had received from Nicolls in the preceding four years,

and the flood showed no signs of crossing. In the end, Boteler achieved

his purpose, but the deluge was to involve the Fortifications department

in the intimate details of the Citadel's construction, and began a long

series of transatlantic exchanges which was to hinder and occasionally

paralyze Boteler's successors.

The first such consultation involved the counterscarp and gallery

opposite the northwest bastion. As this was one of the few areas where

Boteler felt that work could proceed, he wished to be able to start

construction as soon as the weather allowed. There was, however, a

problem. Nicolls's plans were vague. While the ditch deepened at the

salient, the gallery behind the counterscarp was apparently intended to

remain in the same plane throughout the entire length of the wall, with

the result that the loopholes were 6 feet 3 inches above the ditch near

the west ravelin and 9 feet 3 inches above it at the salient. Should he

build the gallery in this fashion, or should he incline it so that the

loopholes were all at the same height above the ditch?13 A

month later, Boteler reminded London of the problem, this time enclosing

a copy of Nicolls's plan of the gallery and stating that the wall would

be built according to plan if he did not receive instructions to the

contrary.14 London finally replied on 25 May.

Sir Alexander Bryce desires that the loopholes be so constructed

that a person immediately under them, and out of fire, may not be able

to reach so as to throw grenades or other combustables into them —

He therefore prefers the higher level of 9'3" . . . unless you find

their construction at that height would leave too much dead ground

immediately under them, in which case you are at liberty to adopt a

lower level provided the ditch be sloped off or sunk so as to obviate

the inconvenience before alluded to from grenades.15

The Inspector General also suggested changes in the construction of

the loopholes, and enclosed a sketch of the new

arrangement.16

Fanshawe's letter did not arrive until the working season was well

under way, and was therefore too late for its suggestions to be of

practical value. Boteler, therefore, politely acknowledged its receipt

and went on to say that he was proceeding along the lines indicated in

his two earlier letters17 — proof, if any were needed,

that the whole object of the correspondence was not so much to elicit

suggestions from London as to make his superiors aware of his

difficulties. In fact, a new problem had arisen since his last letter.

The salient of the counterscarp fell on "made ground" — ground

which had been filled up to form the glacis — and in places the

foundation of the gallery had to be "carried to a considerable depth,

— in one part 12'6" below the bottom of the ditch." Boteler had met

this difficulty by "building up the foundation . . . as far as the level

of the bottom of the ditch." and proposed to erect the gallery,

following the official plan, on top of this. The Fortifications

department, apparently satisfied with Boteler's judgement, did not reply

to his letter.

A month after his questions about the counterscarp and gallery,

Boteler dispatched a long list of statements and questions about the

north and south ravelins.18 He noted that there was not

enough money to complete the gorge of the north ravelin and that he had

insufficient information to commence construction of the guardhouse and

ditch in either. Was it Colonel Nicolls's intention to provide caponiers

for these ravelins? Would it be possible to lower the escarps of both

ravelins by two feet? London's reply took the form of four statements by

the Inspector General in the margin of Boteler's letter.19

The first three dealt with matters of detail. The escarps could be

lowered, if this did not expose the revetments of the body of the fort

to distant cannonade; the caponiers were superfluous and cost money; a

sunken area was to be provided around the ravelin guardhouses. The

fourth statement contained an important concession:

Lt. Col. Boteler is at liberty to offer any suggestions which his

local information may suggest; — But in every proposition he may

bring forward, Lt. Col. Boteler must distinctly state; with reference

to the original estimate whether the new suggestions will produce an

excess or saving, and to what amount.

No longer was Boteler explicitly enjoined to preserve economy at all

costs. The tide was beginning to turn in his favour.

As the summer of 1832 wore on, the results of Boteler's tactics began

to be evident in the financial balance sheets. Ironically, the problem

was not that Boteler was spending too much but that he was spending too

little. As we have already seen, when Boteler took over his command

there was over £3,000 unexpended on the Citadel accounts, some of

it money which had been voted as early as 1829. London's response to

this fact was an injunction to spend the money; as long as the total

expenditure during 1832 did not exceed the cumulative grants up to that

time (reckoned at about £71,000) both the Ordnance and the

Treasury would be happy.20 The Inspector General, earlier in

1832, had cut the annual grant by £3,409 17s. 2d. to £17,656

14s. 5-1 /2d., but saw no need for any further reduction.21

This gave Boteler a total of about £20,000 to spend. By the end of

the working season, £3,000 remained unused.22 The

failures of the preceding four years had taken their toll. Too much of

the work could not proceed without some sort of guidance on basic

matters such as the shape of the fort and the means of remedying the

failures, as well as specific information on lesser topics such as the

height of the escarp and the arrangement of the loopholes. A coherent

policy could be formed only in the light of detailed information which,

it had become apparent, neither Boteler nor London possessed. A few

plans Nicolls's brief and insufficiently detailed estimates and a few

dozen letters were all either side possessed, and these were not enough.

The work was in a state which bordered on paralysis.

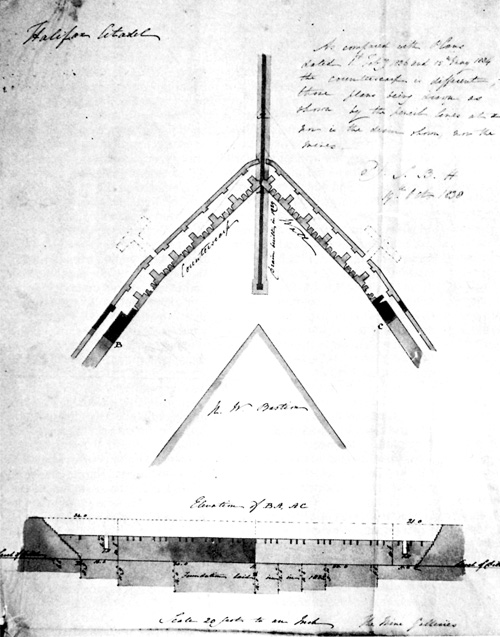

11 Plan and elevation of the counterscarp and gallery opposite the

northwest demi-bastion, 1838. This particular section of the

counterscarp had been begun as far back an 1831 and was still in the

course of construction. Difficulties encountered in its construction

resulted in the change of design of the counterscarp and the abandonment

of the casemates of reverse fire. The chief problem lay in the fact that

counterscarp at this point was being built on made ground, ground which

had been built up with earth excavated from the ditch. This meant that

the foundations had to be excavated to an unusual depth and accounts for

the 14 foot footing at the salent.

(Public Archives of Nova Scotia.)

|

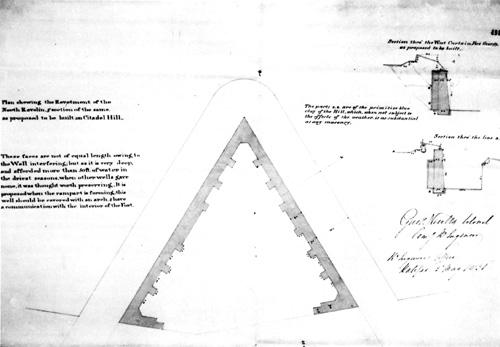

12 "Plan showing the Revetment of the North Ravelin," 1831. The north

ravelin was begun in 1831 and the escarps were carried up to the height

of 20 feet by the end of the working season. No further work was done

for at least seven years. It was not until the 1836 revised estimate was

approved in the summer of 1838 that any funds were authorized for its

completion.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

The major obstacle to the formation of a coherent policy was money.

Boteler seems to have realized from the start that the deficiencies

could not be made good and the work completed for the £116,000

allowed in the original grant. The problem was to convince London of

this fundamental fact. Boteler's chance arose over Colonel Nicolls's

proposed redan. On his arrival in Halifax, he had found a letter from

the Inspector General asking for detailed information on the

project.23 Boteler provided it. Estimate, plan and covering

letter were dispatched on 13 April 1832.24 Having taken pains

in his covering letter to state that he based his calculations on

Colonel Nicolls's original estimate of 1825, Boteler reckoned that the

additional expenditure for the alteration would be between £2,152

4s. 8-1/4d, and £3,254 11s. 2-1/2d. He emphasized that the greater

figure was for the construction of Nicolls's proposal in all respects.

Even this sum only allowed for a 30-foot escarp at the redan salient,

making it substantially lower than the salients of the two adjacent

bastions.

London was quite properly shocked. "Sir Alexr Bryce was not prepared

from Col. Nicolls's letter . . . to expect any excess beyond the

original estimate, even were his propositions to the full extent

sanctioned."25 Once again, the Inspector General demanded the

impossible; Boteler was to remedy the low escarp at the salient, adopt

the full extent of Nicolls's proposal, and stay within the original

estimate.

The Inspector General's letter contained one significant change in

tone. Earlier answers to Boteler's letters had called for reports on

specific problems, but this letter was sufficiently vaguely worded to be

taken as a request for a general report. In addition, Bryce's marginal

annotation of Boteler's enquiries about the ravelin was delivered in the

same packet. The two allowed Boteler the freedom to offer suggestions

based on his knowledge of local conditions. London had finally given

Boteler a loophole, and, in the autumn of 1832, he prepared to step

neatly through it.

There is no evidence in the surviving correspondence that London ever

requested anything so formal as a detailed estimate for the completion

of the Citadel, but that was exactly what Boteler set about drawing up.

In fact, he produced three of them, and, not content with transatlantic

letters, decided to go to London to argue his case in person. He set out

on the Calypso in late January 1833. He never reached London. The

ship foundered and took Richard Boteler with it.26

Of all the engineers who supervised the building of the Halifax

Citadel, Boteler had the most difficult task. It fell to him to retrieve

Nicolls's mistakes and to force London to recognize the necessity of a

thorough reassessment of the work. Had he lived, the transition from

Nicolls's inadequate planning to the more detailed work which was

necessary for the completion of the fort might possibly have gone

smoothly. His death, coming when it did, was an unmitigated disaster. In

the confusion which followed, the Board of Ordnance found itself saddled

with no fewer than eight different detailed estimates for the completion

of the Citadel, and an administrative stalemate set in which lasted for

more than three years. In the end, the matter was settled as Boteler had

intended, but by then the project had fallen hopelessly behind schedule,

and limped on for another 22 years before finally being declared

finished.

III

Finding a successor to Boteler proved to be no easy task. The new

Inspector General, Major General Robert Pilkington, recommended Sir

George Hoste.27 Hoste, who had been a member of the Smyth

commission, prudently declined.28 The next candidate was

Lieutenant Colonel Rice Jones, the Commanding Royal Engineer at Chatham,

who accepted. By this time the Fortifications department was keenly

aware of the disadvantages of sending out a new CRE without extensive

prior consultations on the course to be followed once the CRE arrived at

the station. But upon what could such consultations be based? The

Inspector General's office had not yet seen Boteler's detailed plans;

they had gone down with the Calypso. A request was dispatched to

Halifax for copies, and Jones was instructed to remain in England until

they arrived.29

When Boteler left for England, his command had temporarily passed

into the hands of Captain Loyalty Peake. Peake had had no part in the

formation of Boteler's estimates, but he was well enough acquainted with

the situation to realize that Boteler's revised estimates exceeded the

amount originally provided for the construction of the Citadel, and that

London would probably not be pleased with them. After Boteler's death,

Peake saw a golden opportunity arising. Rarely had a junior officer been

in charge of so important a project. If he could suggest an economical

solution to the problem, the Inspector General would be certain to

notice him favourably. In any case, he had little to lose. The

difficulties in finding a successor for Boteler and the decision to keep

Jones in England until more information could be gotten from the colony

gave Peake the time he needed, and he used it to draw up four estimates

of his own. Between September 1832 and June 1833, therefore, no fewer

than seven supplementary estimates for the completion of the Citadel

wore formulated.

Of Boteler's three estimates, the most elaborate incorporated all the

changes proposed in the correspondence of the previous

summer.30 The new features incorporated in the estimate

included the redan, two new magazines (each consisting of a pair of

linked casemates in the western bastions) and 16 now casemates, the bulk

of them in the north, west and south fronts. The southern and eastern

counterscarps were to be built without galleries or mines. Granite was

to be substituted for ironstone in the wall facings as "granite is very

abundant in the neighbourhood of Halifax and of the very best

quality."31 The remaining items of the estimate were for the

completion of other parts of the fort according to the original plan.

The total expenditure was estimated at £92,378 5s. 8-1/2d.

Boteler's first estimate was, therefore, his assessment of the

probable cost of implementing the suggestions made by London. Those did

not necessarily accord with his own views, He thought that "it would be

better not to place [?] casemates under the ramparts of the north, south

and west fronts," and he disliked the idea of abandoning the southern

and eastern portions of the gallery and countermines and the south

cavalier.32 He therefore drew up a second

estimate,33 intended to supersede those items in the first

estimate which dealt with the casemates and counterscarp, and to show

the comparative costs of the two schemes. In the place of the casemates,

this estimate proposed a "substantial retaining wall"34 to

take some of the loading weight off the escarps. The estimated cost was

£79,014 2s. 10-1/2d., plus another £10,000 for the south

cavalier.35

Boteler's third estimate36 was intended to supplement

either of the others. The bulk of it was concerned with the probable

costs of making good earlier building, should it be necessary to do so.

The amount of the estimate was £15,975 14s. 1d.

Peake's four estimates were arranged in a similar fashion; the first

three presented alternative schemes for completing the fort while the

fourth dealt with the cost of replacing earlier work. Peake's approach

to the problem was, however, only superficially like Boteler's. Boteler

had begun with the assumption that additional spending would be

necessary in order to complete the work and drew up his estimates

accordingly. He was not an innovator; indeed, as we have seen, he

personally wished to retain the essential features of Nicolls's scheme

and produced his second estimate to show that this could be done at a

reasonable cost. Peake began with the opposite assumption; the Citadel

could be completed for the amount specified in the original

estimate if drastic alterations were made in the physical shape of the

fortress. In proposing such alterations, he altered Nicolls's original

concepts beyond recognition.

Peake was merely continuing a process which had begun with Nicolls

himself. In Nicolls's original idea, the four fronts of the Citadel were

reduced to a regular order by duplication on opposite fronts and by the

uniform provision of auxiliary features like the counterscarp gallery

and mines. Insofar as this arrangement was based on the idea of four

fronts of more or less equal strength, it was a triumph of geometry over

common sense. Nicolls's proposal to substitute a redan on the eastern

front was a recognition of the fact that that front differed, both in

its relationship to the adjacent ground and in its accessibility to any

enemy from the other three. Peake carried this reasoning to its logical

extreme. Each of the four fronts, he argued, was unique; each presented

different problems to an attacking enemy and each had special advantages

or disadvantages for the defenders. With this belief as his starting

point, Peake produced a scheme in which no two fronts were at all

alike.

He left the west front exactly as Nicolls had designed it. Most of

the work had been done, if inadequately, and it would have been too

expensive to make any radical changes. On the eastern front he accepted

the idea of a redan, but considered the counterscarp and gallery

unnecessary, suggesting the substitution of "a palisaded covert way"

instead.37 His argument for this proposal was that the nature

of the ground and the close proximity of the town rendered it

unnecessary to make this front as strong as the others. The north front

he considered the most vulnerable because of

1st The nature of the ground towards the Country (See

Colonel Nicolls plan of 26th December 1825).

2nd The small extent of the Front.

3rd The absence of Flanks.

4th The acuteness of the salient angles tending to

shorten the parapet.

5th The position of the confined Ravelin which masks a

great proportion of the direct fire, leaving not more than 70 feet of

parapet fire upon each face.

To remedy these faults, Peake proposed that "A Caponnier . . . be

added, and the Counterscarp with gallery and mines . . . be continued

from the Salient (N.W.) until it meets the proposed covert way at the

N.E. Salient." The south front was not, he thought, such a serious

problem.

The South Front does not labour under all the disadvantages of the

North Front and the Ravelin has not yet been commenced, any attack

carried on against this side would be subject to annoyance both in flank

and reverse from George's Island, and the Ground towards the country is

less advantageous to an enemy than that to the northward, in fact this

Front may be said to be refused to an attack as it almost faces the

harbour.

He therefore proposed to complete the south front without a ravelin,

but with a wide ditch, caponier, gallery and mines and a covert way; the

last was to be an extension of the one proposed on the eastern

front.

The core of Peake's scheme, therefore, was the use of caponiers. He

listed six advantages to be gained from building them;

1st a sufficient Musketry fire will be obtained.

2nd Less of the interior space of Narrow Ravelins will

be taken up than by the Bomb Proof Guardhouses.

3rd good and easy communication will be established

between the body of the place and Ravelin . . .

4th The Ravelin may be mined.

5th The Caponnieres will give additional Barrack

accommodation for 20 men, making up a total of Barrack room for 700 men

within the work . . . .

6th The platform of these Caponnieres may be made a

little above or upon the same level with the superior talus, although

they will be completely separated from the Body of the place, when

together with the Cavalier already built, they may serve as defensible

points to a late stage of the attack, and may greatly prolong the

defence.

Above all, the caponiers had the advantage of being cheap. They

provided the means by which some of the more expensive features of the

original plans could be dispensed with, and "the several Fronts

completed at a moderate expense and their capabilities of defence nearly

equalized."

Peake estimated the additional money needed to complete his basic

scheme at £53,997 12s. 10-1/4d.38 He produced, in

addition, two variations on it, the first dispensing with the north and

south caponiers and reinstating the south ravelin,39 the

second encompassing both ravelin and caponiers.40 The cost of

the first variant was put at £55,770 9s. 1/4d., and that of the

second at £61,510 10s. 11-1/4d. Peake's fourth estimate, for

tearing down and rebuilding escarps in the southwest and northwest

bastions, amounted to £7,242 8s. 9-3/4d.41

We now come to the difficult problem of trying to ascertain the

amounts by which the various schemes of Peake and Boteler would have

exceeded the original estimate. If any contemporary calculation was

done, no trace of it has been found, and the contemporary material which

survives concerning Citadel expenditure before 1836 is frequently

contradictory. The overall cost was to be computed by adding the

estimated total of the new project to the amount of money already spent

under the original grant. The problem lies in determining the latter

figure. According to Peake, £55,718 had been expended as of 30

April 1833.42 The surviving Citadel account book, however,

states that no less than £86,570 had been granted by the

end of 1833.43 How does one account for the discrepancy? Had

the unexpended balance on the Citadel account increased from

£13,000 to £30,000 in less than a year?

Were the figures in the account book — which was only begun

after 1836 —mwildly inaccurate? Or did Captain Peake manipulate his

calculations to produce the lowest possible figure? Given the

information presently available, it is impossible to tell which

explanation is correct, but the last one is the most likely. The date

Peake chose for his calculations — 30 April — was significant,

since it fell before the beginning of the 1833 working season. By the

time he wrote his letter of 12 June, several thousand pounds more would

have been spent. The calculations which follow are, therefore, based on

the minimum cumulative expenditure under the 1825 estimate; the

total amount needed in excess of the estimate may have been anywhere up

to £30,000 more.

The accompanying table (Table 3) details the calculation of the

excess or saving produced by both Boteler's and Peake's schemes. In the

case of each of the five basic schemes, the total amount of the new

estimate is added to the £55,718 which, according to Peake, had

been spent on the Citadel to 30 April 1833; the sum of these two figures

is the estimated total cost for each scheme. This total is then compared

to the original estimated cost (£116,000, in round figures) and

the excess or saving calculated. To this is added the amount estimated

for rebuilding old work; the total of the two is the total excess. The

difference between the largest and smallest total excesses is more than

£54,000. The least expensive is Peake's basic scheme (Peake's

estimate No. 1) which represents a saving of £6,285 over the 1825

estimate. The most expensive is Boteler's first scheme, coupled with his

estimate for rebuilding, which represents an excess of £48,071. On

paper, at least, the range of alternatives was comprehensive.

|

| Table 3. Approximate Amounts by which the various 1833

Estimates exceeded those of 1825 (for derivation of figures, see

text) |

|

| Boteler

| Peake

|

| No. 1 | No. 2 | No. 1 | No. 2 | No. 3 |

|

| Expenditure to 12 June 1833 | £55,718 | £55,718 |

£55,718 | £55,718 | £55,718 |

|

| Estimated cost of proposal | 92,378 | 89,014 |

53,997 | 55,770 | 61,510 |

|

| New estimated total cost | 148,096 | 144,732 |

109,715 | 111,488 | 117,228 |

|

| 1825 estimate of total cost | 116,000 | 116,000 |

116,000 | 116,000 | 116,000 |

|

| Excess | +32,096 | +28,732 |

-6,285 | -4,512 | +1,228 |

|

| Estimated cost of replacing earlier work | 15,975* | 15,975* |

7,242† | 7,242† | 7,242† |

|

| Total excess | +48.071 | +44,707 |

+957 | +2,730 | +8,470 |

|

*Boteler No. 3.

†Peake No. 4.

On 12 June 1833 Captain Peake bundled up the whole lot — seven

estimates, a covering letter, two explanatory letters, reports by

Captains Wentworth and Rivers, and a list of plans — and sent the

entire collection off to London.44 Altogether, it amounted to

more than 400 folio pages. One can almost hear the gasps of alarm when

this monstrous collection was trundled into the Fortifications

department. Pages and pages of figures, enough to keep the clerks busy

for a month; the very complexity of Peake's report was its downfall.

Colonel Jones was presently to be sent out to the station. He could read

all these documents, of course, but only as a means of increasing his

knowledge of the situation. He must produce his own report —

simple, coherent and (subject to London's approval) final. As for the

fruits of Peake's and Boteler's labours, they were put aside and

forgotten until further alterations were proposed ten years later.

|