Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 17

The Halifax Citadel, 1825-60: A Narrative and Structural History

by John Joseph Greenough

Colonel Calder Revises

I

The Citadel entered the second and final phase of its construction

between 1840 and 1842. In these years the exterior of the fort, as

definitively established by the revised estimate of 1836, was finally

completed. There could be no fundamental alterations. In the second

phase, the fleshing out of the granite and ironstone skeleton into a

functional work of defence, a whole new set of problems arose. The

difficulties encountered in the 1840s were in matters of detail —

accommodation, waterproofing, interior partitions and so on. They

required specific and detailed solutions which, of course, were quite

beyond the general considerations provided for in the revised estimate

and its supporting documents. Indeed, some of the problems were simply

the result of the initial stages of building having taken so long. Many

of the difficulties encountered with the cavalier, for example, arose

from the fact that it was already more than 15 years old when the time

came to make it fit for lodging troops, and it suffered from the

maladies typical of any stone building left unoccupied for so long.

It was during this second phase that continuity in the building staff

became important for efficiency. Colonel Jones had already been in

Halifax for more than seven years and had, in effect, become the

projector of the work. In the process, he had acquired enough experience

with the Citadel to decide on matters of detail. He was also

sufficiently well-established with the London authorities to be allowed

a certain amount of latitude in his decisions. Any successor would have

neither of these advantages.

It was probably for this reason that the Inspector General requested

Jones to stay in Halifax until the work was completed. Then, less than a

year later, London reversed itself. It is not known why. Possibly Jones

himself requested it; he had been in Halifax eight years, longer than

any other Commanding Royal Engineer. In any event, Jones was notified on

19 November 1841 that he was to be relieved.1 His

successor arrived on 8 March 1842.2

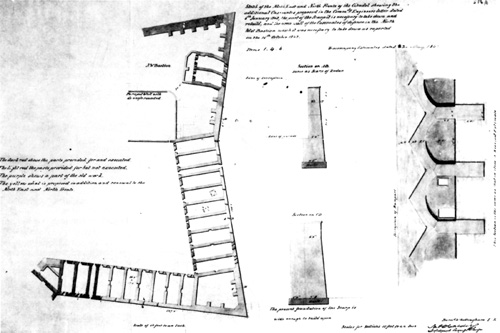

14 "Sketch of the North East and North Fronts of the Citadel," 1843.

This plan shows the additional casemating proposed by Colonel Calder in

his 1843 estimate.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

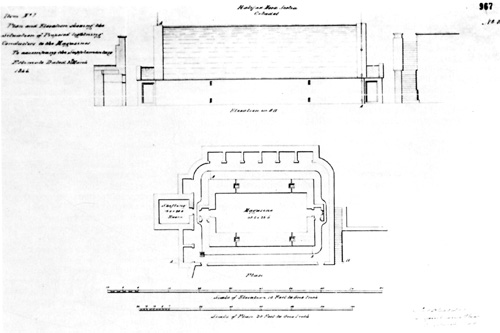

15 "Plan and Elevation shewing the situation of Proposed lightning

Conductors," 1846. The lightning conductors were installed (briefy) in

this fashion and shortly thereafter failed. They were ultimately

replaced by a different system. This is the earliest elevation of the

magazine as built.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

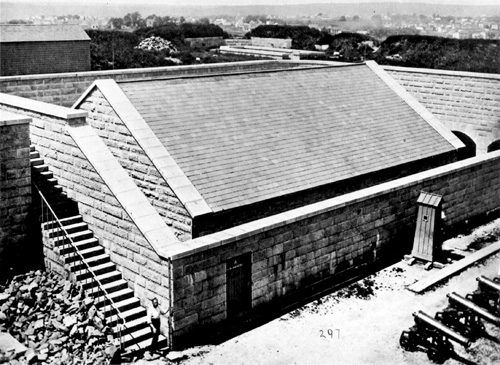

16 The north magazine and area wall, ca. 1880. The south magazine was

identical.

|

II

Lieutenant Colonel Patrick Calder arrived just as the final season of

work on the exterior walls was about to begin. The northern, western and

southern fronts were virtually complete (except for a few problematical

walls dating from Colonel Nicoll's time and a defective west ravelin),

and the escarp and counterscarp on the eastern front were both more than

half finished. The interior of the fort, however, had changed little

since 1832, and indeed since 1828. The old powder magazine still stood,

perched by that time on top of an island of earth in the centre of the

parade square. The new magazines were not yet begun, nor were the bulk

of the casemates; and the cavalier, which looked imposing enough, stood

empty and incomplete.3 A newcomer walking into the place must

have felt rather like a spectator blundering backstage at a theatre and

seeing the sets from behind. Even an experienced engineer like Calder

must have felt some discouragement at the amount of work still to be

done.

The first summer passed quietly. The work done cost £12,742

— about the average amount spent in a working season.4

The only ominous event was the collapse of the area wall enclosing the

stairs leading to the casemates of defence in the northwest bastion. It

was the first such collapse since the early thirties and it immediately

raised the question of the soundness of the other early walls. Calder's

first progress report, dispatched on 30 June, contained an account of

the collapse as well as of the other work in progress.

London's reply set the tone for Calder's relationship with his

superiors for the next two or three years. The chief draughtsman of the

Fortifications office, on examining the progress report, found it did

not agree with his interpretation of the original 1836 estimate. His two

complaints arose from an examination of the drawing accompanying the

report. In one, the redan basement was shown without the area wall

opposite; in the other, the main drain differed from that shown in a

drawing in a previous report. Calder was instructed to account both for

these discrepancies and for the failure of the area wall.5

The collapse of the area wall was easily explained; loading pressure

and the poor quality of the mortar and masonry used in its construction

were to blame.6 The chief draughtsman's complaints were

another matter. Both were essentially trivial and were easy enough to

correct; in the case of the redan basement, Calder's draughtsman had

simply omitted to draw the area wall, since it was irrelevant to the

matter at hand, and in the case of the main drain, an error had been

made in copying the original drawing. But it was obvious from the nature

of the complaints that Calder had not yet acquired the confidence of the

Fortifications staff in London, and that Jones's estimate, detailed as

it was, was still liable to differing interpretations on specific

points. This last fact suggested to Calder that the overall plan was

open to improvement. In his reply to the questions raised by his

progress report, he made his first tentative suggestion for alterations.

Could not two or three new casemates be provided in the rear of the

basement area wall to provide storage space for the officers' quarters?

Such casemates, "though eventually necessary," had apparently not been

foreseen in the original plan.7

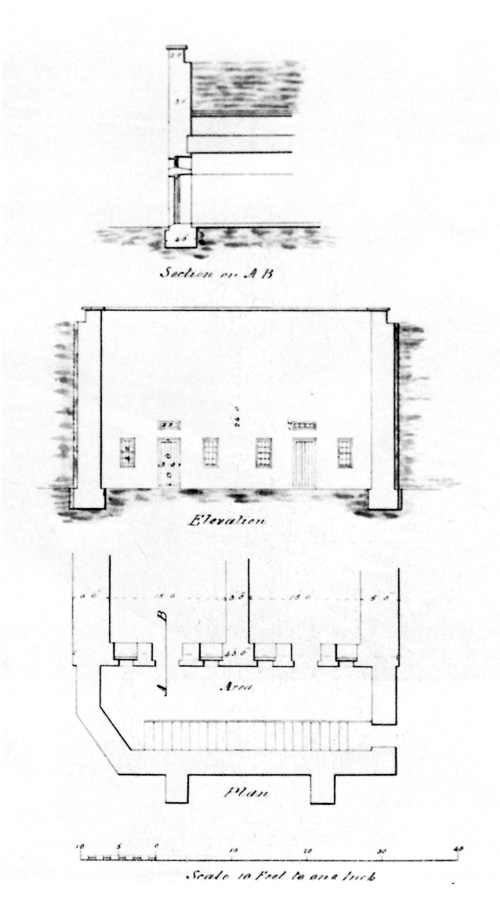

17 "Plan Elevation and Section of Retaining wall to two casemates of

Defence," 1846.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

When the working season ended, Calder finally had the time to examine

Jones's revised estimate in detail. He concluded that it could indeed be

improved upon by a few judicious additions, and on 6 January 1843 he

submitted his proposals for improvement for the consideration of the

Inspector General.8 The tone of his letter was unprovocative

and gentlemanly. He was not attempting to cast aspersions on Jones's

ability, but merely recommending a series of minor improvements which

either were too specific to have been considered within the broad scope

of the revised estimate or had been made necessary by developments since

1836.

The changes included the provision of porches and shifting rooms for

the new magazines, the cellars for the redan (already mentioned in his

letter of 15 October), an alteration in the method of constructing the

arches of the proposed cavalier additions, and the substitution of ramps

for staircases leading to the west ramparts. All of these were minor

changes which tended to increase the efficiency of the completed work at

little additional cost.

Calder also wanted to add more casemates. His argument in favour of

doing so was based on an absurd misinterpretation of Jones's intentions.

The latter had proposed strengthening the interior retaining wall by

building arches over the supporting buttresses to form small cells or

recesses which could be used for a variety of purposes. Calder misread

the wording of the estimate and believed that it had been Jones's

intention to carry the arches all the way through to the escarp. He

noted that this had not been done in the case of those parts of the

retaining wall already built, and went on to argue that, even if it had

been done, the resulting space would have been too narrow to be useful.

He proposed instead the substitution of full casemates in most

instances, two in the re-entering angles of the redan and an unspecified

number on the other fronts.

The collapse of the area wall in the northwest bastion once again led

to a reconsideration of the early work. Calder's opinion was that

The whole of the scarp of the north front (excepting 120 feet of

the right face of the N. W. Bastion) as well as the adjoining face of

the East front . . . [is] in such a state of dilapidation from

the badness of the mortar used in the construction . . . [and]

the inferior quality of the stone and the unworkmanlike manner in

which it is built, as to render it advisable to take down & rebuild

the whole from the level of the ditch.

This, he considered, would account for the bulk of the additional

expense he proposed — £7,000.9 The other features

he proposed could cost, in all, just over £5,000 for a grand total

of £12,620

When Calder's letter was received in London, a copy was immediately

dispatched to Colonel Jones for comment. He replied on 1

March.10 Apart from a mild rebuttal of Calder's

misinterpretation of his design of the retaining wall, he was generally

disposed to accept Calder's judgement. He did differ in certain points

of detail. Jones had a curious theory about magazine construction; he

disliked the idea of external porches and of north-end doors, both of

which he considered unsuitable in the Halifax climate. Consequently, he

suggested alterations to Calder's proposals for the magazines, while

agreeing that porches and shifting rooms would improve the design. He

raised a gentle objection to the proposed ramps:

[They] would give more ready access for guns &c to the Rampart

but yet [they] seem objectionable from interfering with . . . the

breadth of the Rampart at the Flanks.

The judicious wording of the objection is, however, typical of the

tenor of Jones's letter.

A letter from Lieutenant Colonel Edward Matson (the Assistant

Adjutant General of the corps) enclosing the Inspector General's

comments was similar in tone.11 General Mulcaster blamed

Calder's misinterpretation of Jones's design on an incorrect transcript

of the 1836 estimate, and enclosed a true copy so that the Halifax

version might be altered to read correctly. The Inspector General

directed that Jones's plan be followed with respect to the cavalier and

referred Calder to Jones's objection to ramps, but these things aside,

he was willing to consider the remaining items. Additional casemates

could be brought forward as items in the estimates if it was found that

"the casemated accommodation already contemplated [is] insufficient."

The cellar and shifting rooms items were both accepted in principle. The

matter of the magazine porches and doors was referred back to Calder

with instructions to confer with the "Officer of Artillery and the

Ordnance Storekeeper" on the subject. Matson concluded by requesting

detailed drawings and estimates for the proposed changes.

This exchange — gentlemanly, tactful and blandly reasonable

— was in vivid contrast to the acrimonious exchanges which had

greeted Boteler's first letters on the subject of alterations ten years

earlier. Even as recently as 1840, Calder's proposals would probably

have provoked a row, but in the intervening three years, attitudes had

mellowed. The ensuing history of Calder's proposals, though almost as

complicated as that of the 1836 estimate, was relatively harmonious. The

era of bitter controversy was at last over.

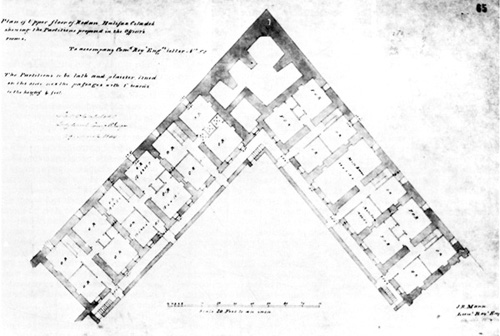

18 "Plan of Upper floor of Redan," 1844.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

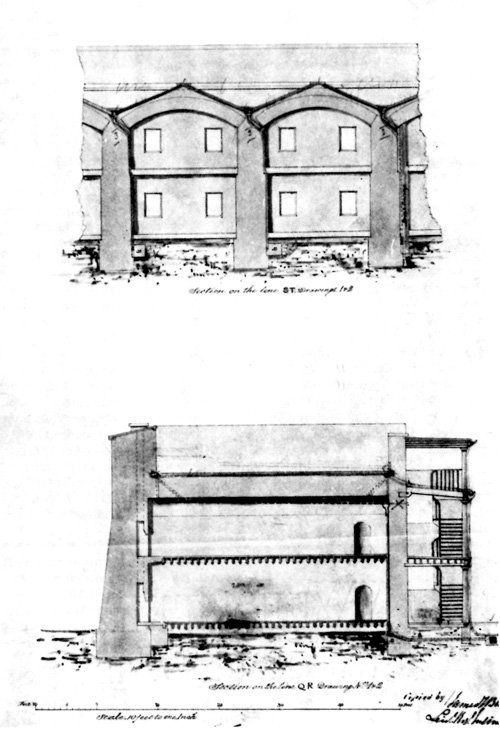

19 "Sections of cavalier showin [sic] the mode proposed for

rendering the arches secure against leakage," 1849. This plan

illustrates the drainage provisions of Colonel Savage's staunching

estimate of 30 April 1849. It is impossible to tell to what extent it

was carried out.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

III

The Inspector General's invitation to justify the increase in

casemate accommodation prompted Calder to do something which no one had

thought of doing before. In late April, he canvassed the other

department heads to find out how much space they would need in the

Citadel, both in peacetime and for a siege of two months.12

Since he wanted an argument for additional casemates, he encouraged his

colleagues to submit the largest possible claims for space. The Deputy

Commissary General replied that he would need three casemates for a

summer siege and at least three more for a winter one. (No commissariat

stores were kept in the Citadel in peacetime.13) The Barrack

Master needed two casemates under any conditions;14 the

Commander, Royal Artillery (CRA), needed at least three;15

the Ordnance Storekeeper, four. This gave Calder a maximum figure of 16

casemates beyond the ones he needed for the normal garrison of one

regiment. He considered this sufficient justification for bringing

forward 16 additional casemates in his new estimate.16

The estimate was completed on 22 May 1843.17 It provided

for all of the features mentioned in Calder's letter, excepting the

ramps for the western ramparts. It also contained provision for fitting

up the rooms over the end casemates of the cavalier and reconstructing

the roofs of the magazines and ravelin guardhouses. In all, it amounted

to £12,879 19s. 7d.

In his explanatory letter, Calder said little which was new. He had

consulted both the CRA and the Ordnance Storekeeper on the arrangement

of the magazines, and they had both accepted his proposals. As for

Jones's objections to doors facing north, he noted that "all the

magazines in Halifax stand north south and that each of them have

[sic] doors in both ends." The two new aspects of the scheme were

scrupulously accounted for. The cells over the cavalier end casemates

were in response to a suggestion from the Major General Commanding. The

substitution of rafters for cement on the dos d'anes of the magazines

and guardhouses was the result of "the latter having shown itself unfit

to resist the effects of this climate in the trials that have been made

on the last mentioned Buildings."

The most interesting features of the covering letters were the three

statements of accommodation appended to them. These were intended to

support Calder's argument for more casemates, and they detailed the

number of men intended for the Citadel's garrison. In all, the fort was

designed for two field officers, 17 officers, 609 NCOs and privates and

39 women (the proportion of soldiers' wives allowed under regulations).

In addition, provision was made for a 35-bed hospital in the cavalier

and a school room, as well as for the usual assortment of storerooms.

The average number of privates per casemate in time of peace was

22.18

London acted very quickly. The Inspector General dispatched the

estimate to the Master General and board on 1 July 1843.19 In

his accompanying letter, Mulcaster briefly reviewed the background of

the proposals and recommended their acceptance.

The Estimate amounts to £12,879 . . 19 . . 7 and although

its details have not yet been investigated by the Surveyor and some

internal Fitments are omitted, it may I apprehend be taken as an

Estimate sufficiently approximative to enable the Master General and

Board to determine upon the additional Bomb proof accommodation and the

omissions and renewals . . . which had not been originally provided for

or have become necessary.

He admitted that the renewals were "discreditable to the department,"

but could see no way of avoiding the expenditure. He concluded,

Should the Master General and Board sanction the view I have taken,

after a careful consideration of the above named Reports and

circumstances, I propose making the necessary communication without

delay for the Commanding Royal Engineer's guidance, in proceeding with

the construction, and that the detail of the several additions be

examined annually as they may be provided for in the Estimates for

Parliament.

The board took less than two weeks to decide in favour of the new

estimate,20 and authorization was dispatched to Halifax on 18

July.21

IV

The method proposed by the Inspector General of approving funds for

the new estimate signalled the beginnings of a change in the Ordnance

accounting system. At some point between 1844 and 1847, the

authorization of each item of expenditure as it arose in the annual

estimates became standard procedure (in contrast to the old system of

approving a general estimate and making annual grants against it). The

new system had obvious advantages. It eliminated the embarrassment of

over-running the original grant, as the Citadel account did at some time

between 1847 and 1849 (the accounts for these years have not been

located). It also, however, had one disadvantage. Like all changes, it

produced a certain amount of confusion during its transitional stage.

Not all the people involved understood the significance of the change,

and one who did not was Patrick Calder who, in 1846, submitted yet

another supplementary estimate for the completion of the Citadel.

The origins of this document are obscure. On the title page, it was

credited as being in response to the Inspector General's letter of 18

July 184322 authorizing the earlier estimate for alterations.

But the surviving copies of the Inspector General's letter of that date

contain no indication that such an estimate was requested or even

contemplated. Possibly Calder genuinely misread the letter; possibly the

title page was wrong and the new estimate was in response to a later

communication from London, since lost. Unless new evidence comes to

light, it is unlikely that we will ever know the truth of the

matter.

In its format, the new estimate reflected the new accounting system.

The items were divided into six classes:

(1) Works first detailed in Calder's first estimate for

renewals, and subsequently authorized in the annual estimates for

1844-45 and 1845-46.

(2) Works from the same source, brought forward in the current

annual estimate and not yet approved.

(3) Additional services found to be necessary since the 1843

estimate.

(4) Services in the 1843 estimate "ordered to be brought

forward as excess."

(5) Works necessary because of failures.

(6) Services necessary for the installation of the

armament.

Of the 17 items, 14 were new since 1843. These included water tanks,

a well on the glacis, flagging for the areas, lightning conductors for

the magazines, water pipes and gargoyles for surface drainage, flagging

for the cavalier dos d'anes, fitments for the casemates, and a picket

fence around the glacis to keep out trespassers. In addition to the new

features, provision was made for rebuilding works which had been

considered adequate three years earlier. These included the west ravelin

in its entirety and six casemates of defence (four in the curtain and

two in the northwest bastion) which had been part of the initial

construction. Calder had intended to provide for curbs and platforms for

the guns, but since no decision had ever been formally made on the

armament of the work, he was unable to estimate the overall cost of the

service. The entire estimate amounted to £26,563 3s. 1-3/4d.

Calder's covering letter was brief. It repeated the time-honoured

phrase used by successive engineers in submitting revised estimates: "I

have reason to think the amount of this estimate . . . will complete the

work."23 He went on to say that he had considered returning

to the use of caponiers, but had discovered that they had been removed

from Jones's first estimate for reasons of economy. Apart from this, and

a few comments on the lack of information about armament, he let the

estimate (which was the most detailed one yet drawn up for the project)

speak for itself. His arguments for each individual feature were

contained in the preamble of each item. Thus the rebuilding of the west

ravelin was necessary because "the gorge [had] fallen down carrying

with it part of the guardhouse"; besides this, the escarp faces had

"cracked from the foundations upwards in several spots."

One feature of the estimate was Calder's emphasis on securing an

adequate water supply. He considered the two wells insufficient for a

garrison in the event of a siege, and proposed two complementary methods

of supplementing them. The first method involved the construction of two

water tanks under the casemate next to the guardroom "to be supplied

with rain water collected from the ramparts of the work by the surface

drains" (item 4). The second involved the provision of protected access

to a well on the glacis near the northeast salient (item 5). The means

of access proposed was a tunnel, like a countermine, from the

counterscarp gallery. These two, in conjunction with the two existing

wells would, Calder considered, be enough to supply the fort.

The new Inspector General's assessment of the estimate was favourable

but cautious24 (John Fox Burgoyne had been appointed to the

post in July 1845.) He was disposed to accept most of the new features

as "desireable" with the exception of the picket fence, which was, he

thought, extravagant. But Burgoyne withheld final decision until he had

better information. He therefore ordered that the document be returned

to Calder for revision, that the CRA in Halifax be consulted on the

subject of armament and that a scheme be submitted to the local

commander of the forces for approval.

By the middle of July, Calder and Colonel Jackson (the CRA) had drawn

up the armament proposal (see "... and keep your powder dry!"

below).25 Calder then proceeded to revise his estimate. Most

of the revisions were minor. Asphalt was substituted for flagging in

the magazine areas and an entry (item 3-1/2) was inserted for providing

area walls in all three ravelins. Calder still did not estimate for the

number of curbs and platforms needed for the proposed armament, although

he did provide for 19 curbs for dwarf platforms, 12 wooden ground

platforms and 12 wooden mortar platforms. The bulk of the revision

consisted of alterations in the calculation of expense. The overall cost

of the works proposed in the new estimate was put at £27,977 10s.

2-1/4d. excluding armament.26

Calder's explanatory letter was, as usual, brief. He enclosed a list

of replies to the specific points raised by the Inspector General, and

the armament proposal, signed by Colonels Calder and Jackson, and

endorsed, as Burgoyne had instructed, by Major General Dickson, the

General Officer Commanding in Nova Scotia. The replies, for the most

part, revealed that Calder agreed with the Inspector General's opinions

except in the matter of the picket fence. Calder maintained that

Burgoyne had misinterpreted his original suggestion.

The enclosure proposed for the Glacis is a common picket fence and

not palisading. It is very near as cheap as an ordinary post and rail

fence, and affords greater protection against trespass of every

description in a Country where whatever belongs to the crown is almost

considered a common good, more especially where land has for a length of

time lain unenclosed and been dailly [sic] overrun by cattle,

goats, geese, &c.

Calder requested that the lightning conductor estimate be revised in

London according to the most approved opinion, this being a subject

"where such diversity of opinion" existed. He debated the virtues of

enclosing the ravel in guardhouses with an area:

[It] would be an improvement as a work of defence was the interior

space sufficiently large, and it would render the building more

wholesome in some situations, but in this Climate where a deep narrow

ditch is liable to be filled with snow . . . it is apprehended that the

walls might receive more injury and the building be less fit for

occupation than at present.27

He concluded that proper drainage would meet at least some of the

objections.

London answered on 15 September. Calder was instructed to bring

forward the items providing for the water tanks, the well, the magazine

areas, the lightning conductors, the water pipes and the cavalier roof

in ensuing annual estimates. The Inspector General stood firm on the

subject of the glacis enclosure and instructed Calder to substitute a

post and rail fence for his proposed pickets. Calder's objections to the

ravelin areas were also dismissed:

Your objection to the ditch or area to the guardhouse would apply

to all ditches and Buildings in that climate if care be not uniformly

and constantly taken day by day to keep the footings of all buildings .

. . clear of snow.

He was, therefore, enjoined to bring forward estimates for the areas

when "the guardhouses in these outworks require reconstruction." As for

the artillery plan, it was at present being considered by the Director

General of Artillery and Calder would be notified when it was finally

approved.28

The same day that this response was sent, the Director General wrote

to Burgoyne, pronouncing himself satisfied with the artillery

proposals.29 The proposals were then submitted to the Board

of Ordnance, which communicated its approval on 10 October.30

A week later notice of the decision was dispatched to

Calder.31

In his letter instructing Calder about the disposition of his

proposals, the Assistant Inspector General, Colonel Edward Fanshawe,

reminded him to adhere in future to the new system of annual accounts

and to submit proposals for new works in the appropriate annual

estimate. This spelled the end of the tradition of all-inclusive Citadel

estimates. Calder's revision of his second supplementary estimate was

the thirteenth32 and last of a long and frequently confusing

line. The change was symbolically appropriate. Despite all the disasters

and crises of the preceding decades, the Citadel was visibly nearing

completion, and major estimates were no longer appropriate to the

situation.

It is a striking fact that all five engineers who held the post of

Commanding Royal Engineer between 1828 and 1846 felt it incumbent on

them to draw up large-scale estimates for the Citadel. Quite apart from

the fact that the majority of these estimates were in response to

genuine needs, we can, I think, discern in this pattern an attempt by

each of the engineer officers to impose his own ideas on the work, to

leave a monument to himself. To a greater or lesser extent, all five of

them succeeded. But after Colonel Calder, no engineer had this

opportunity. Calder's successors did not even have the chance, unlike

Boteler, Peake and Jones, to gain some satisfaction from correcting, or

trying to correct, someone else's disastrous mistakes. Calder's

predecessors (excepting Nicolls) may well have looked on the work with a

certain amount of satisfaction. To his successors, it was nothing more

than an embarrassment.

Already in 1846 one future source of trouble was beginning to develop

— hardly a disastrous problem, merely an irritating one which

seemed to have no easy or permanent solution. It was becoming evident

that the majority of the new casemates had a disconcerting tendency to

leak.

|