Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 17

The Halifax Citadel, 1825-60: A Narrative and Structural History

by John Joseph Greenough

". . . and keep your powder dry!"

From Ballads of Ireland, Col. Oliver's

Advice, Valentine Blacker

I

The attempts to staunch the casemates absorbed most of the energies

of the engineering staff at Halifax during the last decade of the

Citadel's construction. The problem involved was fundamentally the

result of four different but related factors. The first was the

necessity of completing the casemates in such a way as to allow them to

perform their allotted functions effectively. This was vastly

complicated by the second factor: pressure from the military authorities

to use them as barracks. The third factor, in some ways the most

frustrating, was the age of the work. A good many of the casemates had

been standing empty for years before the construction finally reached a

stage where they could be put to use, with the natural result that the

process of staunching involved both building and repairing

simultaneously. The fourth factor was the inadequacy of the original

design. This was less because of incompetence on the part of Colonels

Jones and Calder; the casemates were of comparable quality to those

built elsewhere. But no one knew precisely what features could be used

effectively in a permanent fortification in the damp Halifax

climate.

These same four factors underlay the difficulties experienced with

other parts of the work carried on at the same time as the staunching.

The problem of waterproofing, moreover, ultimately affected almost all

the other parts of the fortress. While the casemates remained

unfinished, the ramparts, armement and parade ground could not be

completed: the magazines could not be used except as storage depots for

other works in the Halifax area, and the glacis could not be built.

There was simply not enough labour to do all the work at once. This

inevitably exacerbated the age factor, since the longer the remainder of

the work was postponed, the more decrepit the existing buildings became.

In the end the engineers found themselves caught in a kind of

nightmarish race to get the fortress finished before its aging fabric

went irretrievably rotten.

The last decade of construction was, therefore, characterized by

interconnected routine work, with the dominant theme of casemate

staunching played out against a counterpoint of increasing urgency. The

period can be divided into three phases. In the first, lasting until

about 1850, the momentum of building continued, all the while being

gradually slowed and interrupted by the growing demands of the

waterproofing problem. At this time the final provisions of the revised

estimate were carried out and the last attempt was made to introduce new

features into the original plan. By the end of this stage, it was

obvious that the primary concern was not improving the work but

preserving what had already been built. In the second phase, lasting

from 1850 to about 1854, the waterproofing brought almost all other work

to a complete standstill, while the decay of the older portions of the

masonry was accelerated. In the third phase, from 1854 to 1856, all the

problems, delays and faulty judgements of the previous quarter-century

finally came home to roost, and the project came closer to foundering

completely than it had at any point since the early 1830s.

The most characteristic activities of the first phase were the

removal of earlier failed work and the abortive attempt to introduce

prison casemates; of the second, the attempt to install the armament.

The third phase was characterized by an almost frantic attempt to renew,

restore on rebuild parts of almost all the major components of the

fortress, including the cavalier and magazines. Even the casemates.

after almost 10 years of continuous labour on the problem of

waterproofing, remained a major source of worry and complaint. In the

end, disaster was averted, but it had been (to use a Wellingtonian

phrase) "a near run thing."

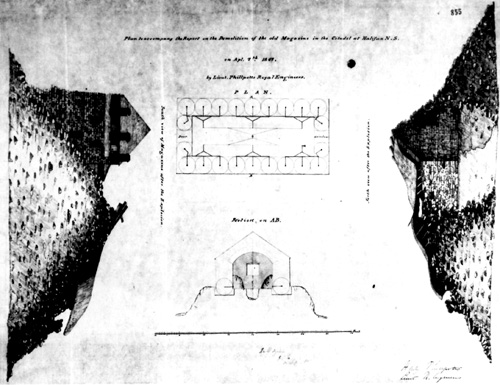

25 "Plan to accompany the Report on the Demolition of the old Magazine,"

1847.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

II

By the mid-1840s, one of the few remaining routine tasks which did

not involve the casemates was correcting earlier mistakes and

removing those features of the early design no longer felt to be

necessary. The first casualty was the old (1812) magazine, which had

been standing empty for 19 years and obviously impeded the completion of

the parade square. In the spring of 1847, Calder got permission to

remove it. As it was an almost embarrassingly solid piece of work, the

Fortifications department did not want to spend the time and effort

necessary to demolish it by conventional means. The only alternative was

to blow it up, and even this took considerable time. Between 24 March

and 6 April, working parties laboured with crowbars, picks and sledge

hammers on the business of constructing galleries in the masonry walls

for the gun powder charges. In all, 22 chambers were cut into the walls

and were packed with charges of between 9 and 16 pounds of gunpowder

each.

On 7 April, everything was ready. The officer in change of the

demolition described the results.

The charges being fired, the foundations were blown away, the

walls rose about 3 feet, and falling with a low rumbling sound, crumbled

to pieces, hardly two stones being left together. Not a stone was blown

50 yards from the building.

The arch, of course, fell in; all the charges exploded except the

four in the North Angle which was consequently left standing . . .

.

The demolition was most complete, and the magazine now presents

the appearance of a shapeless mass of ruins.1

Colonel Calder pronounced himself pleased with the operation. Indeed,

he was so impressed with the speed and efficiency of the demolition that

he proposed similar measures for one of the other failures earmarked for

removal.

I beg to propose the removal of the West Ravelin (which is to be

taken down and rebuilt) by a similar process, but for this I consider it

necessary to obtain your [Burgoyne's] sanction, as to effect it

about 20 barrels of gunpowder will be required, an expense which will be

amply covered by the diminution of labour.2

Calder waited almost a year for a reply to this proposal. When it

finally became important to get the matter settled so that he could

proceed with the rebuilding of the ravelin, he dispatched an informal

query to London. "Col. Calder presents his compliments to the Inspector

General of Fortifications and begs to acquaint him that the last

paragraph of his letter No 193 . . . has not been replied

to."3 The fact was that London had lost the original letter:

one of the clerks had to annotate the margin of Calder's query, "I

cannot put my hands upon the origl letter No

193."4 When it was finally found, the Inspector General

responded by asking Calder why he wanted to proceed with the scheme.

Calder restated his reasons.5 After another delay, Burgoyne

decided to forbid the use of explosives in the demolition on the grounds

that it might be possible to re-use some of the stone from the west

ravelin in rebuilding.6

This ended the brief vogue for dramatic demolition of old mistakes.

In fact, apart from the two cases mentioned above, a surprisingly small

amount of the supposedly defective work of the early period was ever

altered. Most of the work in question was, of course, in the escarp

walls, and some of the basic rebuilding and repairs there had already

been done by Nicolls and Boteler in 1831-32. Colonel Jones

estimated in 1834-36 that only 574 feet of the remaining old walls

would have to be rebuilt.7 This was only a portion of the

original escarp and it was demolished by means less dramatic than

explosives. In the end the engineers made do with the remaining old

walls, partly because the masonry in question, though shoddily built,

showed a complete disinclination to collapse. After the demolition of

the west ravelin in 1848-50, the whole question of the old work was

shunted aside and partly forgotten. It was not until 1855 and under

rather different circumstances that it became again an issue.

III

As the last of the old work was being removed, Colonel Calder made

the last attempt to introduce a new feature into the overall design of

the Citadel. This was in response to a peculiar and specific sort of

accommodation problem. The first soldiers to have the honour of

inhabiting the Halifax Citadel had been the military convicts. As early

as 1845, a strongroom and guardhouse had been fitted up for prisoners

in two of the defence casemates (Nos. 54 and 55).8 This was

apparently only a temporary arrangement to serve until cells designed

for the purpose could be built. Such cells were included in the 1843

estimate for alterations and renewals and were to be located above the

end casemates of the cavalier.9 But even after the cells were

built there was still not enough room for the convicts. On 7 August

1847, Calder submitted a proposal for 12 more cells to be placed under

the ramparts on the south side of the southeast salient.10

His design called for a complicated arrangement of two-storey arched

compartments connected by a corridor at the rear. He estimated the total

cost of the scheme at £2,410 19s. 7-1/2d.11

London not only approved the scheme but, in a rare burst of

generosity, actually enlarged upon it. Calder shortly received a revised

design which included two additional compartments for first-class

prisoners and a more complicated system of heating and ventilation. The

only objection which the Ordnance raised was to the proposed location of

the new work. The south face of the southeast salient was considered

inappropriate because of the lack of space available for the enlarged

scheme, so it was suggested that the work should be put on the east side

of the salient.12

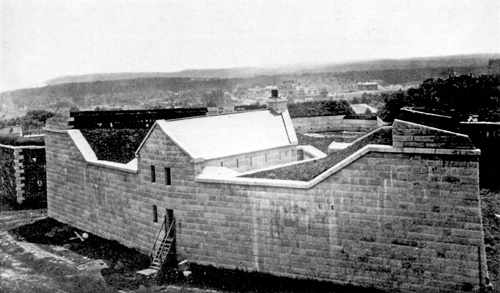

26 The west ravelin rearmament, ca. 1875. The rearmament of the ravelin

consisted of cutting an embrasure at the salient and removing one

embrasure from each face.

|

Calder, doubtless amazed at this unexpected development, could only

concur. He incorporated all the changes and re-submitted the design

on 15 November.13 Even as he was doing so, however, London

was having second thoughts about the whole project. The problem of

accommodating prisoners was essentially an army matter, and the Ordnance

had seen fit to submit the scheme to the Secretary at War for an

opinion. The secretary, Mr. Fox Maule, disliked the idea and decided

that it would be better policy to build a gaol large enough to hold all

the garrison convicts somewhere outside the Citadel.14 The

Board of Ordnance accepted the recommendation and instructed Burgoyne to

inform Calder.15 In the end, the cells over the cavalier

cookhouse remained the only military prison within the fortress.

IV

It was not until 1846 that the Ordnance staff in Halifax addressed

themselves to the task of composing an armament proposal for the

Citadel. In that year, Lieutenant Colonels Calder and Jackson (the CRA)

drew up a scheme which entailed 94 pieces of ordnance, including five

8-inch guns, thirty-one long 32-pounders, eighteen short 32-pounders,

twenty 24-pounders, twelve mortars and eight howitzers (see Table

4).16 On 15 September 1846 the Director General of Artillery

approved the plan and initiated the process of

installation.17 Almost ten years elapsed before the bulk of

the armament was installed.

|

| Table 4. Proposed Armament, 1846* |

|

| Location | Guns

|

Mortars

| Howitzers

|

|

| 8 -in.,

9'0" | 32-pr.,

9'6" |

32-pr.,

6'6" | 24-pr.,

6'0" |

13-in. | 8-in. |

8-in. |

|

| South front |

| 3 |

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

| West front |

| 6 | 2 |

|

2 |

| 4 |

|

| North front |

| 4 |

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

| East front |

| 8 |

|

|

| 2 | 4 |

|

| Salients, all fronts | 5† |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| North ravelin |

|

| 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

| South ravelin |

|

| 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

| West ravelin |

|

| 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Salients, all ravelins |

| 3† |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cavalier |

| 7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Casemates |

|

|

| 20 |

|

|

|

|

| Total | 5 | 31 | 18 |

20 | 2 | 10 |

8 |

|

*Adapted from a return in PAC, MG12, WO55, Vol. 880, p. 913.

†One in each salient.

The first stage of the process involved the manufacture of carriages

for the guns, the acquisition of the guns themselves, and the

construction of the stone platforms on which the greater part of them

would be mounted. The first matter was the responsibility of the Royal

Carriage Department; the second, of the Board of Ordnance, and the

third, of the Engineer department in Halifax. Since a coordinated

interdepartmental effort was involved, delay and complications were

inevitable, and it was well over two years before all the orders were

filled.

The most serious misunderstanding arose over the order for 24 siege

gun platforms after Lieutenant Colonel Alderson's pattern. These were

intended for mounting the mortars, howitzers and four of the

32-pounders.18 The Ordnance staff in Halifax included them in

the order for traversing platforms and carriages sent in to the Carriage

department in the spring of 1847.19 Two years later the

Carriage department decided that the platforms might not be their

responsibility. The gentleman in charge. Mr. Gordon, wrote to General

Burgoyne,

I feel assured you will excuse my addressing you point blank (as

the saying is) upon the enclosed order for Halifax.

I made inquiry from the Assistant Director General of Artillery

thereon, and he gives me the dates and authorities only, but I want

measurements or working plans and I am sensible you will afford me such

as to enable me to carry out this outstanding order.20

After some discussion, the Board of Ordnance decided that the

Carriage department ought to be relieved of the task of making the

platforms, and instructed Burgoyne to ask the Commanding Royal Engineer

in Halifax why they had not been included in the Engineer Demand of

Stores in the first place.21

By the time this finally got back to Halifax, Colonel Savage had

replaced Calder as Commanding Royal Engineer. Savage had no idea why his

predecessor had requested the platforms from the Carriage department,

and could only promise to include them in the Ordnance annual estimate

as required.22 By then it was obvious that the armament could

not be mounted at all until the problems of waterproofing the casemates

were solved, and the whole question of equipment was temporarily

sidetracked. Fortunately, the Artillery was in no hurry to mount the

guns and, except for the occasional enquiry on technical matters,

nothing more was heard about armament for two years.

By the spring of 1851, however, the Director General of Artillery was

beginning to get impatient. The CRA was requested to report on "the

condition of the fort with respect to its state of preparation for

mounting the Ordnance."23 The CRA relayed the request to

Colonel Savage,24 who answered that the Citadel would not be

in any state to receive armament until the summer of 1853. Even this

date proved optimistic. When the question was put to him again in

January 1853,25 Savage was able to approve the mounting of

only part of the armament for the following summer.

[The] following description & number of Guns may be mounted

viz:

5-8 inch — 9' 0" long at Salient angles. —

10-32pr — 9 . . 6—" on Cavalier & Ravelin

— 20-24d° — 6 . . 0 —" — In Casemates —

16-32d° — 6 . . 6—" — Ravelins.26

The remainder could not, he thought be mounted until the following

year.

The Ordnance did its best to prevent Savage from carrying out his

plans for 1854. The mounting of armament on the rest of the work

depended on the completion of the staunching project and the

construction of the ramparts and terreplein. While the former appeared

to be going ahead successfully, London prevented the latter by refusing

to allow Savage the sum provided for the service in the annual estimate

for 1853-54. Three months after he had given his optimistic prediction

to the CRA, Savage wrote to the Inspector General proposing that the

funds allotted for completing the glacis be used instead for the

terreplein and parade.27 London replied with surprising

speed, granting permission to make the substitution.28 Since

the work was not included in the annual estimate for the following

year,29 it would seem that the ramparts were constructed in

the summer of 1853, and, in all likelihood, most of the rest of the

armament was mounted the following summer.

Whether it would stay mounted was another matter. By the fall of

1854, serious questions were being raised about the future of the

cavalier, and after a brief period of optimism, it was becoming

depressingly evident that the casemates were still displaying a

pronounced tendency to leak.

V

The first indication that parts of the Citadel were falling to pieces

came on 19 October 1852, when the Ordnance Storekeeper, Mr. Ince,

discovered that the door of the north magazine would not open "in

consequence of something having fallen against it."30 On

examination, Colonel Savage discovered (probably to his horror) that

"the floor, which was previously in a decayed state, had suddenly given

way, from the weight of the powder and the decay of the

joists."31 Savage had already provided for repairing the

floor in the annual estimate for the following year, but the sudden

collapse took him by surprise, and he could no longer wait for the

estimate to be authorized. He therefore requested that the Respective

Officers formally propose a special estimate. The Respective Officers

replied three days later:

We have to request you will immediately take the necessary steps

to bring the subject under the notice of the Inspector General of

Fortifications with a view to obtain as soon as possible the Master

General and Board's authority for the repair of the floor for the

preservation of the powder.32

The next day, Savage formally requested permission to make immediate

repairs, stating that the expense could be defrayed from the savings on

various items of the annual estimate for the preceding

year.33 London was quick to authorize the expenditure, and

the repairs were carried out in the course of the

winter.34

In spite of his experience with the north magazine, Savage was

somewhat startled when, a few months later, he examined the floor of the

south magazine while alterations to the powder bays were being made:

I was led from the appearance of a depression in the surface of

the floor, to examine its state beneath . . . it was found that the

joists, plates and boarding throughout were in the last stage of decay,

evidently from the same cause that rendered necessary the renewal of the

floor of the north Magazine, and which makes it absolutely

necessary to renew this floor before the bays can be arranged or the

powder again stored therein.35

This discovery made it necessary to formulate yet another special

estimate, but this time Savage decided to use a new method of repairing

the floor. Acting on a suggestion from the Surveyor of the Ordnance, he

proposed to use

fine Seyssel Asphalte without grit in lieu of the joists and

planking, which substitution I consider may be effected as an

experiment, as it is probable that asphalte in this situation, not being

exposed to the direct action of the weather it [sic] may be found

to answer to the desired end.36

He enclosed a special estimate and a demand for stores amounting to

£158 5s. 0d.

Despite the fact that Savage's suggestion was made at the height of

the asphalt mania, London decided that it would not be appropriate to

use the material on the magazine floor. General Burgoyne recommended

that the floor be repaired in the same way as the one in the north

magazine (apparently with a new wooden floor) and the board approved his

recommendation.37

The two magazine floors were repaired and the buildings restored to

normal use by the summer of 1853. There followed a brief respite. It was

to be a year and a half before the next serious problem arose.

VI

By the fall of 1853, Colonel Savage thought that the end of the

Citadel construction was in sight. The Ordnance annual estimate for the

following year reflected this belief. There were only two items in it

for the Citadel.38 One, amounting to £2,681 12s. 3d.,

was for the completion of the glacis and parade square, and this was

believed to be the last major expenditure on the work. The Assistant

Inspector General wrote, in forwarding the estimate to the board, "With

the sum here proposed the Coming Rl Engineer

expects to complete the Citadel in 1854-5."39

The second Citadel item for £1,256 2s. 11d. was for the renewal

of the cavalier colonnade and was considered absolutely necessary for

the occupation of the building by troops. This was an ominously large

sum to be spent on repairs, but it could easily be explained. After all,

the cavalier was almost 25 years old and repairs were a matter of

routine in a building that age. At this point, no one seriously

considered more drastic measures to be necessary.

This mood of optimism lasted for some time. In February, Lieutenant

Parsons drew up his memorandum on the effectiveness of asphalt in the

Citadel; while he admitted that it had not worked in the case of the

cavalier, he did not speculate on the reasons.40 In

forwarding Parsons' report to London, Savage noted that

the very imperfect state of the Escarp and Retaining walls of the

Cavalier erected many years since, render any attempts to secure it

against leakage short of rebuilding the upper part of it, a measure of

considerable difficulty, if not an impossibility.41

Apart from this observation, which Savage appended almost as an

afterthought to a long report, the whole question of the cavalier's

suitability received little attention either in Halifax or in

London.

When Lieutenant Colonel Richard Stotherd inherited Savage's command

in June 1854, it seemed that he would have the good luck to be the first

Commanding Royal Engineer in more than a quarter-century to avoid

trouble with the Citadel. His first summer, in fact, passed quietly

enough. The only matter concerning the Citadel which needed particular

attention involved a special estimate (amounting to £22 12s. 10d.)

which provided for altering the position of the stoves in the cavalier

to keep the casemates warm in winter.42 This was approved by

London in just over a month.43 Stotherd's first annual

estimate, dispatched on 25 September, asked for only £1,902 for

the Citadel, most of it for completing the glacis. Only £100 was

for staunching the casemates and there were no items at all for

repairing the cavalier.44

But during the winter of 1854-55, two events occurred which shattered

the satisfaction of the Ordnance staff in Halifax, at least in regard to

the Citadel, and Colonel Stotherd found himself faced with the worst

crisis in the fortress's history since Colonel Nicolls's walls collapsed

in 1830.

The first event was a systematic examination of the casemates in

November 1854. This revealed that, despite all the measures undertaken

in the preceding eight years, 21 of the casemates were to some degree

damp. The extent of the problem varied from casemate to casemate. Some

were only slightly wet: others were uninhabitable. The rampart

casemates, however, were in relatively good condition compared to those

in the cavalier. Except for the small end casemates and the rooms over

them, the entire building was completely uninhabitable.

A very considerable extent of dampness is observable in the upper

rooms and which penetrates for the most part to the lower floor . . . .

The dampness arises chiefly from the very defective masonry of the

escarp and retaining walls which admit the wet through the joints so as

to penetrate beneath the asphalte. Owing to the frost of last winter,

there is reason to believe that the Asphalte is considerably injured

beneath the earth of the Terreplein.45

Stotherd reported all this to London in a rather gloomy letter. He

was particularly dissatisfied with the cavalier.

It is now evident that a very considerable expense will have to be

incurred to make the building water tight and habitable, apparently

owing to the defective nature of the masonry in the external walls . . .

. such is the state of the walls that it is considered doubtful whether

the firing of the heavy ordnance mounted thereon would not shake the

walls considerably or possibly bring them down.46

As for the ramparts casemates,

I regret to inform you [Burgoyne], notwithstanding the

hopes entertained by my Predecessor that the approved application of

Seyssel Asphalte would be successful in securing them against leakage,

that some of them have recently become damp from the percolation of

water through the Arches: — whether this arises from Cracks caused

by the frost during the previous winter, or from fractures in the

coating arising from the pressure of the overlaying shingle and earth,

aided by the heavy traffic in getting up and mounting the platforms and

guns, it is impossible to determine without opening the ground which at

this season cannot be effected owing to the frost.47

He estimated that complete repairs would cost around £6,000,

most of which would be needed to repair the cavalier, where he proposed

to rebuild the entire top of the building from the springing of the

arches up. He was less explicit about dealing with the leakage in the

rampart casemates, but apparently he contemplated a continuation of the

existing system of staunching.

Two weeks later, Stotherd dispatched a second letter requesting an

immediate delivery of asphalt so that work on the casemates and cavalier

could begin as soon as practicable in the spring.48 The

response was surprising. After nearly 10 years of experimenting with

asphalt in the Citadel, the Fortifications department was beginning to

wonder whether it was, in fact, entirely suitable for waterproofing in

the Halifax climate. The Assistant Inspector General, Colonel George

Judd Handing, wrote back, enquiring whether "flat tiles laid in cement"

would not be more suitable.49 One wonders whether Harding

was aware that his suggestion had been tried before, with indifferent

results, by Colonel Jones more than 10 years earlier.

27 A modern impression of the appearance of the cavalier prior to the

installation of the permanent roof in the summer of 1855.

|

Before Stotherd even got Harding's suggestion, the second, disastrous

event occurred. On 8 February 1855 Halifax experienced one of its very

rare earthquakes, and among the most vulnerable buildings in the entire

city was the aged, decrepit and top-heavy cavalier. The report on the

damage, submitted by the Clerk of the Works and two of the junior

engineer officers, Captains Philip Barry and Henry Grain, was possibly

the most pessimistic summary even produced in the entire course of the

Citadel's construction.

We are of opinion from the vast quantities of water discharged

through the arches and walls [of the cavalier] during the heavy

rains of the past week, that the shock must have, to some extent,

contributed to the further disturbance of the masonry so as to increase

the leakage . . . .

The external walls appear, to a very considerable extent, to be

splitting or separating longitudinally through the centre from top to

bottom, owing to the expansive action of the frost on the moisture in

the masonry, and which under present circumstances there is no

possibility of preventing, nor does it appear to us, that there is any

mode of repairing, at a future period, those defects, short of taking

down and rebuilding the whole of the external walls, as no pinning or

pointing would avail to render them secure in the event of a recurrence

of Earthquake, much less to bear the concussion from discharging the

guns at present placed on top.50

They concluded by recommending that no attempt be made to staunch the

arches while the walls were "in a condition apparently so irremidiable

[sic]."

A second report, appended by Captains Barry and Grain, was if

possible even more outspoken than the first:

We . . . would beg to suggest, that in a Military point of view it

may be well to take into consideration the value of the Cavalier as a

work of defence. — To us it appears not to be well calculated for

its object in that particular, its greatest advantage ls that of

affording quarters for troops, and therefore, and as the escarp of the

curtain of the West front is fast approaching a state of delapidation,

which must in a few years make its reconstruction absolutely necessary,

it may be worth while to consider the propriety of constructing

casemates under the ramparts to afford the requisite

accommodation.51

The two officers then went on to suggest that the cavalier be

demolished to make way for "a tower . . . to mount three or four heavy

guns" which would both fulfill all the military functions of the

cavalier and allow more space in the fort's interior.

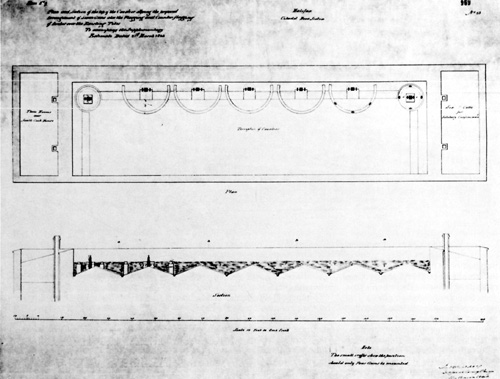

28 "Plan and Section of the top of the Cavalier showing [sic] the

proposed Arrangement of Seven Guns also the Flagging and Counterflagging

of Arches over the Existing Tiles," 1846. The flagging and

counterflagging detailed in this plan wer ultimately superseded other

materials (most notably asphalt), but the curbs, pivots and racers were

installed as shown here.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

This second report was not only outspoken, it was downright

dangerous. In a mere half-page, two junior officers had managed to

question the wisdom of the original designers of the Citadel, revive an

idea which had been forgotten for nearly 30 years, and, worst of all,

raise the whole question of the old remaining contract masonry which had

been often condemned but never replaced. One can imagine Stotherd's

reaction when he read it. It was beginning to look as if the major work

in his command was about to disintegrate.

In forwarding the reports on the earthquake damage to London,

Stotherd adopted a cautious, almost contradictory stand on the

suggestions contained in them. He began by confessing that, since it was

his first winter in Nova Scotia, he was far from being an expert on the

effects of the local climate. He then went on to state that, in its

present condition, he could not recommend the staunching of the upper

parts of the cavalier. But he was uncertain about the best course to

adopt.

The proposition of Captains Barry and Grain . . . to form

Casemates under the Curtain of the west front, with a tower in the

centre, in lieu of the Cavalier is worthy of consideration, for the

reasons they adduce, and I shall await your instructions to have it

regularly brought forward with Plans &c —

On the other hand, he noted that the cavalier had once been

a very useful building, and I am strongly of the opinion that it

should revert to that state and be made available for shelter for

troops, and for stores, by covering it with a wooden roof similar to

that which I understand existed prior to the attempt to secure the

arches from leakage.52

Such a roof would, he estimated, cost around £600.

The Ordnance was not disposed to accept any radical suggestions. In

fact, the whole apparatus of the Ordnance department was under

tremendous strain because of the Crimean Wan, and the department was to

undergo a major revolution in the near future. The officials in London,

uncertain about their own futures, were not about to make major

decisions. Their only response to Stotherd's letter and the gloomy

reports it enclosed was a brief note asking whether it was necessary to

restore or replace the building at all. No mention was made of the

possibility of tearing the cavalier down, and Stotherd was requested to

report on the "extent of the repairs required" so provision could be

made for them in the annual estimate for the following

year.53

This was virtually the last instance of the Board of Ordnance

handing down a decision on matters relating to the Citadel.

Appropriately enough the board ended its superintendance of the work on

a note of administrative equivocation. Stotherd was enjoined to await

events. He did not have to wait long; events were quick to catch up with

him. He was soon facing both a political challenge from forces which had

never before had any effective control over Ordnance works, and the

pressures of providing necessary services within the Citadel. The first

of these, which was to be the most difficult to manage, will be

discussed later. The second was to shape the concluding stages of the

construction of the work.

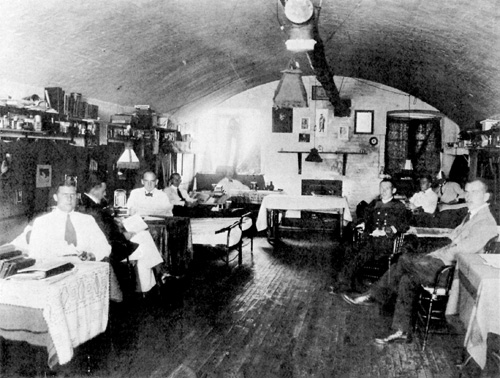

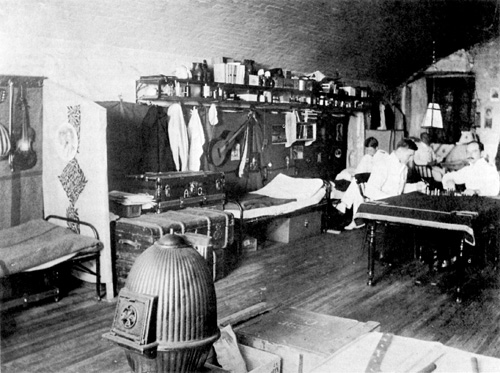

29 The interior of the redan casemates, ca. 1890.

(Public Archives of Nova Scotia.)

|

30 Interior of one of the redan casemates, ca. 1890.

(Public Archives of Nova Scotia.)

|

VII

London was wrong in assuming that the cavalier was of little

importance to the Halifax garrison. It was true that the station was

well below strength in the winter of 1854-55 because most of the British

army was in the Crimea. Even the small remaining garrison, however,

needed more barrack space. On 21 June Stotherd submitted an estimate

amounting to £944 0s. 7d. for the restoration of the

cavalier.54

The scheme put forward in the estimate was essentially an elaboration

of the roofing proposal which Stotherd had made at the end of his

February letter. Besides installing a timber roof, it proposed to alter

and enlarge the chimneys, to point the defective masonry joints and to

whitewash the rooms. This implied the abandonment of the cavalier as a

defensive work. Although the guns were left in place, the enlargement of

the chimneys and the installation of the roof would make it difficult to

get the gun positions cleaned for action in time of war and impossible

to fire them in peacetime.55

Authority to proceed with the scheme was quickly

forthcoming.56 By August Stotherd was able to report that he

expected to be finished with the work within two months.57 By

this time, Stotherd had found solutions to most of the remaining

problems of the Citadel. He no longer thought in terms of major

alterations, but only of minor repairs which, he hoped, would be

sufficient to silence criticism of the work and to keep it in a

tolerably good state of repair. It is difficult to escape the conclusion

that most of the items proposed were at least partly cosmetic in nature,

but they did at least manage to keep everyone satisfied. In this rather

undignified way, the Citadel project limped into its ultimate stage.

The nature of Stotherd's work is demonstrated by the type of item he

inserted in the annual estimate for 1856-57. Of the £2,900

estimated for the Citadel, over two-thirds (£1,795) was for minor

repairs of one sort or another, including £959 for repairing the

asphalt over the arches, £38 for pointing the arches in the redan,

and £529 for pointing masonry in the escarps, counterscarps and

magazines.58 This list covers two of the three major sources

of complaint (the old escarps and the waterproofing) in the cheapest

way possible.

In a report on the defence of the Nova Scotia command, submitted at

the same time as the annual estimate, Stotherd defended his policy,

especially in regard to the pointing.

[The] Curtain has been too long left in a most disreputable state

and the comparatively trifling sum [£528 17s. 10d.]

required for the extensive and very necessary repairs to the Scarps

and Counterscarps of two long neglected fronts together with the

pointing of the two magazines and their enclosures will, in my opinion,

be most profitably expended.59

The effectiveness of Stotherd's measures was varied. His assessment

of the strength of the old walls was borne out by subsequent experience

with them (see "The Very Model of a Modern Major General"). The

experiment with the roof of the cavalier proved equally successful. A

tabular statement of the condition and usage of the casemates drawn up

in June 1856 reported that there was only a slight appearance of damp on

the west wall and this could be easily corrected by additional pointing

of the masonry.60 The same statement revealed, however, that

Stotherd had been less successful with the other casemates. A surprising

number of them still leaked or showed evidence of damp on one or another

of their internal walls. The report treated each case individually;

there was no longer any attempt to assign blanket causes for the

problem. One was damp because of faulty drainage; another because of

decaying masonry; a third because the terreplein had not had time to

settle properly — and so on, down a whole list of similar minor

faults. In other words, the problem had reached the stage where it could

be treated as a minor housekeeping difficulty, and no further large sums

of money were needed to correct it.

As for the other features of the fort, most required only minor

alterations. Most of the armament had been installed.61 After

a bad start, marred by the complete undrinkability of the water, the

water tanks were in the course of being repaired.62 It was

not a particularly heroic ending but, with the exception of the glacis,

the Citadel was virtually finished.

|