|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 15

A History of Martello Towers in the Defence of British North America, 1796-1871

by Ivan J. Saunders

The Construction and Arming of the Kingston Towers: 1845-63

The six round stone towers erected at Kingston, Upper Canada, between

the years 1845 and 1848 were a politically expedient and only marginally

militarily efficient response to the dangers posed to the defence of

British North America and to the British army in Upper Canada as a

result of the Oregon crisis of 1845-46. They incorporated significantly

innovative structural and external features designed to adapt them to

the gradual evolution of the defensive art and the firepower of heavy

smoothbore American naval ordnance. However, they began to be obsolete

by the time they were completed in 1848. This process was virtually

finished by the time they were finally armed in 1863. The Kingston

towers represent the culmination of the cycle of employment of round

masonry towers in British North America. Given the date and

circumstances of their construction, these towers must be examined as

political and technological barometers of change rather than with a

single-minded emphasis on their intrinsic military value. They never

made any significant contribution to the military and naval security of

Kingston.

These towers, in addition to being the last examples of their type

constructed in British North America, were the final phase of the very

long process of erecting works for the defence of Kingston, begun with

the establishment of the first Fort Frontenac there in 1673. Kingston's

location at the confluence of two great inland water routes had early

recommended it to France as a point of strategic importance. It was a

defensive bulwark to the French settlements on the river and a supply

depot and offensive military and naval base sustaining their imperial

ambitions to the south and west, and the French occupied the fort

continuously until forced to abandon it to the English in 1759.

With the collapse of New France, this strategic junction was of small

importance to a power indisputably pre-eminent in eastern North America,

and Great Britain could afford to abandon it. After 1776 the British

preferred to establish a fort and naval base on nearby Carleton Island

rather than at Kingston. Not until 1788, in consequence of the imminent

loss of the island base as a result of the peace of 1783, was the naval

establishment transferred to Point Frederick and Navy Bay at Kingston.

It immediately became the principal British naval base on Lake Ontario

but, because the Americans' power in the interior was in its infancy,

almost no measures were taken for its defence until the commencement of

the War of 1812.

The nature of the American campaigns in that war and an unsuccessful

American naval attack on the town in 1812 clearly delineated Kingston's

importance to Great Britain. With its permanent loss or destruction all

naval operations to the west and a continuation of the naval contest for

the control of the lakes would be immediately impossible. Consequently

its defences were improved, so that before the end of the war they

consisted of an irregular fort on Point Henry, a battery on Murney's

Point, and a five gun battery on Point Frederick which had been added to

the hastily prepared 1812 defences.

While the War of 1812 clearly demonstrated the necessity of retaining

Kingston and the naval control of Lake Ontario, the peace that resulted

in the Anglo-American naval agreement, and Lord Bathurst's order of 10

October 1815, prohibiting new defensive expenditures at Kingston,

quickly eliminated any chance of its rapid military

development.1 Kingston's urgent needs were immediately voiced

in the fortification report commissioned by Governor General Sherbrooke

in 1816 and submitted to Lord Bathurst, the Secretary for War, late in

that year. It accorded great importance to Kingston as the depot and

dockyard of Upper Canada, and proposed its permanent defence by

improving Fort Henry and erecting round masonry towers to the north of

it as outworks on the landward side. It also recommended round towers as

keeps for batteries on Point Frederick and Cedar Island.2

This report contemplated only a defence of the Point Frederick naval

establishment. Sherbrooke himself was a proponent of towers and he may

have influenced their suggested use at Kingston.

No action was taken on this proposal, but it reinforced the views of

the Duke of Richmond, who envisioned Kingston as the citadel of Upper

Canada with a role analagous to that of Quebec in the lower province. He

believed it would provide a secure retreat for shipping and a staging

point for reinforcements sent into the interior against the Americans.

Richmond's scheme was taken up by the Duke of Wellington, the newly

appointed Master General of the Ordnance, who incorporated it into a

submission on British North American defence that he made to the Earl of

Bathurst in March 1819.3 Wellington was never very interested

in or sanguine about a successful defence of British North America, but

by the weight of his military reputation he exerted a disproportionate

influence on its development. He held the cabinet post of Master General

until 1827 and remained a consultant on military affairs for many years

afterward. His views also dominated the Smyth Commission of 1825, which

exerted a direct influence on policy at Kingston and elsewhere until

1845. The Smyth report's vestigial remnants remained in evidence until

the Jervois reports of 1864 and 1865. Wellington was a proponent of

sound and secure communications; as such he was dubious of the British

ability to maintain even the naval command of Lake Ontario in a future

war and was certain that the St. Lawrence River route would be cut west

of Montreal. In consequence he proposed an elaborate system of

alternative water routes to the north of the existing vulnerable one.

The most likely of these, the Ottawa-Rideau system, would debouch at

Kingston, which, in any development, was posited as a vital

communication centre and defensive anchorage, in addition to its

existing roles as a military base and naval depot. In view of its

importance. Wellington recommended its thorough all-round

defence.4 Despite the changing fashions of its proposed

defence, his 1819 view of Kingston's importance, substantiated by the

completion of the Rideau Canal system in 1832, was never seriously

challenged before the 1860s.

A new Kingston defence plan was articulated by the commission headed

by Major-General James Carmichael Smyth, R. E. This report, submitted in

September 1825, recommended the building of the Rideau Canal and the

defence of Kingston by permanent works, as it was only 30 miles from the

important American naval base at Sackets Harbor, New York, and was

subject to reduction by coup de main by a naval attack alone, or

by a naval attack in conjunction with an assault by American troops

landed nearby. The commission considered a naval attack on the military

and dockyard establishment on the eastern side of the harbour more

likely to be of serious consequence, and so did not contemplate a

permanent defence of the town of Kingston or it western land approaches.

Defence on this direction was commended largely to fieldworks and

available land forces.

The commission felt the existing defences were well placed but too

hastily and badly constructed to be of much permanent use. Consequently,

it recommended that Fort Henry be improved and that the existing

batteries at Point Frederick and Mississauga Point be enclosed and

defended in the rear. It further proposed that the naval defence be

augmented by a two-gun tower on Cedar Island to prevent a landing in

Hamilton Cove, and that a strong tower be erected on Snake Island near

the main shipping channel to serve as a keep for a battery to be erected

there in an emergency. It also proposed to erect another tower l,000

yards, in advance of Fort Henry to defend the approaches to the

dockyard. Most of the 1812-14 blockhouses, to the rear of the town were

defunct and the Smyth Commission proposed substituting a single

centrally located enclosed work there as a keep and rallying point for

an emergency line of fieldworks. In total, the commission recommended

spending £201,718 at Kingston. Most of it was to be used to turn

Fort Henry into a respectable fort requiring a regular heavy artillery

siege for its reduction.5

The committee's report on the feasibility of defending British North

America by means of the Rideau Canal and a few strategically located

forts quickly met a positive response in Britain. By March 1826 the

Master General, the Duke of Wellington, had approved such works for

Montreal, Kingston and the Niagara frontier. Additionally, there were to

be a number of ancillary works scattered along the frontier and the

approaches to Montreal.6 As valuable and necessary as the new

Fort Henry was recognized to be, in forcing an enemy to divert a

considerable force to undertake siege operations against it before

proceeding to an all-out attack on Montreal and Quebec, it was clear

that the fort could perform only a limited local defence role because of

its lack of outworks and remoteness from the commercial harbour and the

entrance to the canal, A number of permanent supporting defensive works

were deemed necessary, and the nature and extent of these works were to

be the subject of a prolonged controversy that culminated in the

construction of the Martello towers after 1845.

In June 1826, Lieutenant Colonel Wright, the commanding Royal

Engineer in Upper Canada, was ordered to make a further report and draw

up detailed plans for the recommended Kingston works. In February 1827,

he reported himself in substantial agreement with the Smyth Commission

except that he felt the security of the dockyard required two additional

detached stone towers in advance of Point Frederick. Although his view

was sustained by his superior, Colonel Durnford, the commanding Royal

Engineer for Canada, it was objected to by Major General Smyth.

He did not dispute the desirability of such towers, but argued that

this avenue of approach to the dockyard would afford an enemy no more

facilities than he would already possess if he were in control of the

weakly defended town and could bombard it from there. By October 1827

Smyth had been overruled and the extra towers accepted. Work was to

begin with Fort Henry and the next priority was accorded to the Cedar

and Snake Island towers.7

The whole scheme was negated by the treasury, which balked at the

expenditure. In 1828 another commission composed of Lieutenant Colonels

Fanshawe and Lewis was appointed to bring in an estimate within the

authorized limit of £186,087. They failed in this, although their

report effectively reversed the priorities of the Smyth Commission by

proposing the reduction of the size and prominence of the new Fort Henry

to a large casemated redoubt and advocating a more balanced all-round

defence of town, harbour and dockyard by means of a landward arc of

redoubts and towers. This arc would extend from Hamilton Cove to Murney

Point and operate in conjunction with the proposed and existing sea

batteries and towers. This plan was finally adopted in England on 24

October 1829.8

Once again the Treasury objected to the cost, now estimated at

£273,000, and would not agree to even a modified version of the

plan until January 1832. The Treasury was finally convinced that each of

the small components of the system could be given separate financial

authorization and an immediate and general authorization of a large sum

avoided.9 While this 1832 compromise was a useful short-term

expedient which facilitated the commencement of Fort Henry in that year,

it was to wreak havoc with the military priorities of the overall

development plan. In this way it was instrumental in a second 1845

compromise that produced the four main Martello towers.

The 1832 compromise contemplated the eventual construction of the

Cedar and Snake Island towers, three towers and two casemated redoubts

to the rear of Points Henry and Frederick, three casemated redoubts

behind the town, improvement of the existing Point Frederick and

Mississauga batteries, and a tower and battery on Murney Point, in

addition to the major work on Point Henry. Most of the landside works

were intended for sites that were private property. As early as 1828

Fanshawe and Lewis had recommended that all of the necessarily extensive

purchases be carried out before the plan was known and land prices

inflated by piecemeal acquisition.10

The nature of the 1832 compromise made such a rational expedient

impossible. The treasury was unwilling to approve large speculative land

purchases for works which it must have felt would never be entirely

completed. Consequently when it was desirable to expand Kingston's

defences in the early 1840s, the purchase price of the necessary land

was estimated as high as £100,000.11

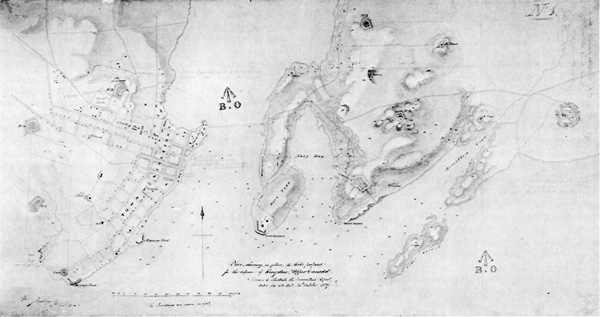

5 Plan of the city and harbours of Kingston, Ontario, 1829, showing the

location of the works approved in the new defence plan of that year.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Fort Henry was completed by 1836 and an advanced sea battery was

added to it by 1842. Before this, however, the Rideau Canal had been

completed and Kingston had become the military, naval and logistical

pivot for the whole western end of the Canadian defence line. With the

emerging acceptance of the general failure of a policy of permanent

fortifications in the early 1840s, the recognition that American naval

control of the lakes would be almost impossible to dispute, and a return

to a theoretical reliance on well-supplied field forces with good

communications, the retention of Kingston became even more essential.

Its sudden loss would mean a termination of operations to the west and

could lead to the whole western army being cut off and

humiliated.12 George Murray, the Master General of the

Ordnance, asserted in 1842 that, "upon the possession of Kingston will

depend, more than upon that of any other place, the possession of the

Upper Province."13 Consequently the further fortification of

Kingston came to be seen as second in order of priority after Quebec. By

1845 its importance and vulnerability were important factors behind the

hastily prepared tower proposed for that year.

While nothing was accomplished before 1845, detailed plans for

extending the Kingston towers and redoubts were in train as early as

1838 in anticipation of the completion of the Fort Henry works, though

final plans for them were not prepared until 1841. This great delay was

of little consequence, for as early as 1840 the dormant land question

had asserted itself in the form of an estimate of £57,920 for

purchase of the sites of the five redoubts and the Murney Point position

alone. Land prices were vastly inflated by speculators hoping that

Kingston would become the seat of government and, although a few small

purchases were made, it was very soon evident that some alteration in

the original defence plan would be necessary. If this were to be so,

Colonel Oldfield quickly recommended abandoning the town-side redoubts

and concentrating on the eastern side and harbour defence

works.14

These doubts as to the viability of carrying the whole plan into

effect, and Sir Richard Jackson's concern with the overall defences of

the provinces, prompted the Master General of Ordnance, after

consultation with Lord John Russell, the Colonial Secretary, to order a

further review of the whole defence question with a particular emphasis

on Kingston.15

The Inspector General of Fortifications, Sir F. W. Mulcaster,

promptly replied that the Kingston works could not be diminished without

a sacrifice to the security of the town, harbour and dockyard, and

recommended the commencement of a redoubt and two towers, but only if

the land necessary for all the works was previously

purchased.16

The intractability of the Treasury Board made such a course

impossible and, in fact, in 1842 it suspended the expenditure of

£10,000 already voted by Parliament for the Kingston works as it

would tend to have an inflationary effect on land prices.17

This suspension was predicated on the expectation of the early passage

of a vesting act by the Canadian legislature. This act would have given

the British government powers of expropriation. Even if, as the colonial

secretary believed, its power could not be generally used, the act would

deflate prices to some extent. The act was passed at the end of

1843.18

By that date the pendulum had swung once more and George Murray,

Master General of the Ordnance, had explicitly abandoned any intention

to defend the town of Kingston with permanent works. He declared that

all works should be limited to the eastern side of Kingston harbour

where most of the land was already in possession of the ordnance, and

all necessary additions. could be purchased for

£5,795.19 Murray claimed to have formed this impression

on a brief visit there in 1815. and by 1843 he found it sustained by

exorbitant land costs for works that the expansion of the town might

soon render useless. His view was accepted and incorporated into the

revised Kingston defence priorities forwarded to Canada in September

1843, although the 1829 defence plan was not formally

revised.20

Even this, more modest proposal was thwarted by the treasury when, on

1 April 1844, it refused to countenance any further cash land purchases

whatsoever, limiting the ordnance to such property as it could acquire

by exchange. The ordnance reported that as long as it was bound by the

formal terms of the 1829 plan it possessed no exchangeable land at all.

At this juncture some formal alterations of the accepted plan became

inevitable. In May 1844, Colonel Holloway, Commanding Royal Engineer for

Canada, was instructed on the orders of the colonial secretary to submit

a revised plan for the defence of Point Henry and the

dockyard.21 At this point the whole Kingston defence question

had returned in principle to the views of the Smyth Commission of 1825,

with its restrictive idea of defending only those points of immediate

military consequence.

Until 1844 the Kingston defence question was approached with the

lethargy and inefficiency so typical of the peacetime military

establishment. This attitude changed abruptly with the election of James

K. Polk as president of the United States in November of that year. In

the summer Polk had campaigned on a demand for the control of the entire

Oregon Territory and spoken of the annexation of the whole of British

North America. Given the chauvinistic fervour of American politics, the

British military was not alarmed, Polk's continuing belligerence after

the election, however, brought the spectre of an Anglo-American war much

closer and prompted the British government to a hasty re-evaluation of

the woefully inadequate defences of British North America.

Scattered large permanent works had been found to be militarily

inadequate and financially impracticable. Given British naval supremacy

and the prospects of a diplomatic settlement to the crisis, the imperial

government was unwilling to authorize large speculative increases in the

regular army in British North America. This caution may also have been

conditioned by the desire to avoid a military disaster to the regular

army in the Canadian interior where it was at such a manifest

disadvantage. A lack of permanent works and an unreinforced regular

force placed a premium on the vigour and reliability of the militia in

the early stages of any conflict. By 1845 British officialdom was

casting about for some cheap, speedy and useful mark of an enduring

interest that would at once reassure the populace and its military

forces and serve some useful military purpose. Robert Peel, the prime

minister, stated that large works proceeded too slowly and in

consequence could have no military value or salutory effect on Canadian

morale.22

Under these circumstances Kingston, with its pivotal position and

role, was the ideal site for some display of preparatory ardour, and the

construction of Martello towers was the ideal expedient. Their political

value was, of course, only one of a number of factors contributing to

the government's eventual course of action, but, notwithstanding the

military necessity of retaining Kingston, it appears to have been at

least as important as any other in the decision to construct only a

marginally useful range of towers that left Kingston fully exposed to an

assault from the landward side.

The continuing governmental concern with the defensibility of

Kingston was substantiated by George Murray's statement in September

1844 that he did not believe Kingston to be defensible against a

combined military and naval attack.23 While little of a

permanent nature could be done quickly and cheaply on the land side, the

naval and commercial harbours were amenable to improvement because most

of the necessary sites had been retained from the outset as crown

military reserves. The need for more formidable harbour defences had

also increased over the preceding few years with the appearance of

American steam war vessels on Lake Ontario. Kingston was fully exposed

to winds from the lake, and light harbour defences had sufficed against

sailing vessels, with their restricted power of manoeuvering

independently of the wind and engaging in heavy stationary

bombardments.24 No such restrictions applied to

steamships.

It was this resurgence of naval considerations that apparently moved

Lord Stanley to order, on 23 January 1845, immediate plans and estimates

prepared for the defence of the dockyard and entrance to the Rideau

Canal from attack by a naval force. In the atmosphere of barely

suppressed emergency prevailing in 1845, and under considerations of

time, expense, impressiveness and utility, it is hardly surprising that

the engineers turned to Martello towers as the most likely means of

meeting the terms of Lord Stanley's directive. Such towers had been a

suggested and versatile component of Kingston's defences since 1816 and

fully detailed drawings had already been prepared.25

Consequently, it was possible for Colonel Holloway, the commanding Royal

Engineer for Canada, to return preliminary plans and estimates for a

system of naval defence towers and batteries as early as 12 June 1845. A

shortage of time and staff, however, precluded a fully detailed

submission; these towers were adopted much as proposed.

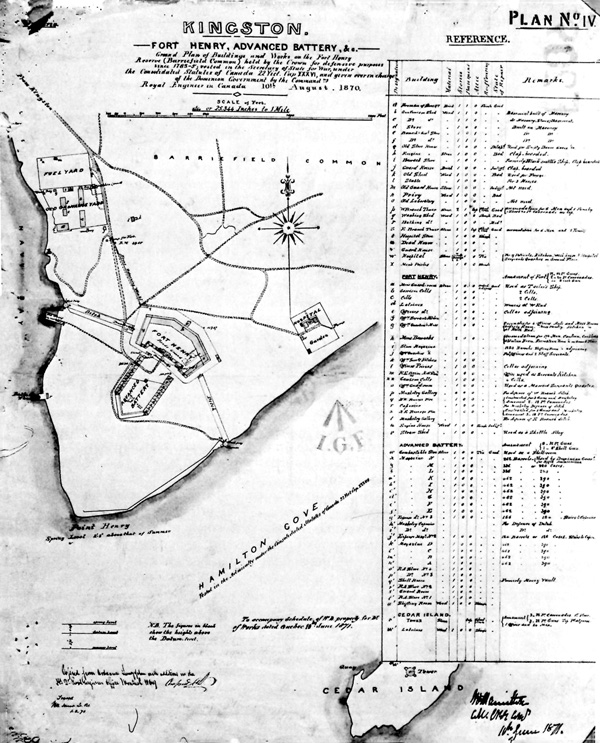

6 Plan of Point Henry and Cedar Island, 1871, showing the location of

the Branch Ditch and Cedar Island towers, with notes on their structure,

armament and capacity.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

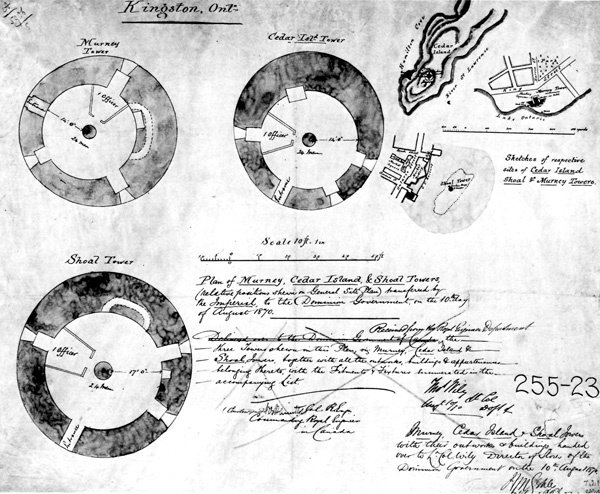

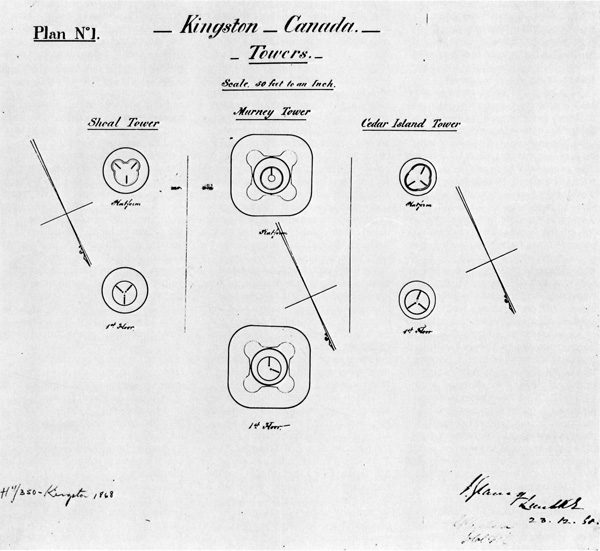

7 Location sketches and barrack floor plans of the Shoal, Murney and

Cedar Island towers, 1870.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

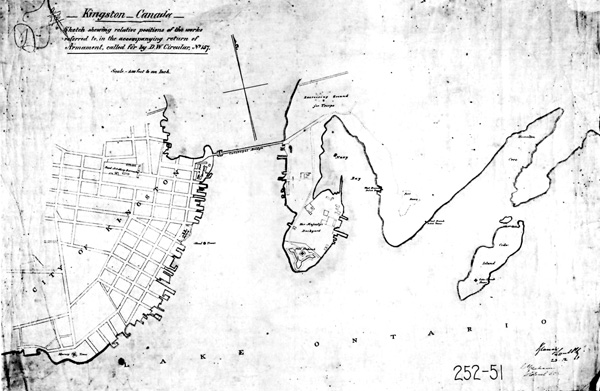

8 Plan of the town and harbours of Kingston, Ontario, 1869, showing the

location of the existing defence works.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Holloway opened his proposal by adverting to the fact that the full

security of Navy Bay and the commercial harbour required that the

defences of Fort Henry be made as complete as possible. This in turn

would require construction of the redoubt and towers in advance of it,

as proposed by the commission of 1826. However, he said,"I am not sure

whether the master general considers their construction under the

existing circumstances to be indispensable for the present design of

securing the harbour,"26 and went on to detail his new

suggested tower locations. He first suggested re-positioning the

long-proposed Cedar Island tower at the southern extremity of the island

so it could better cooperate in the general defence of the harbour. He

next deemed it advisable to reform and improve Fort Frederick as an

earthen sea battery for heavy guns, closed in the rear by a loopholed

musketry parapet, with a masonry tower in the centre as a keep, mounting

three 24-pounder howitzers. Holloway also recommended that a tower for

two 32-pounder guns and one 24-pounder howitzer be placed on the shoal

in front of the town. This tower would be slightly in advance of a new

heavy battery to be placed on the military reserve on the waterfront

directly in front of the Market House. In time of war the Market House

itself could be used to defend the gorge of the battery. Because of

Murney Point's distance from the shipping channels and other works,

Holloway considered it only an auxiliary to the lake defences and

recommended defending it with a tower rather than by the sea battery

recommended in 1829. Holloway believed the above works would provide a

secure naval defence at a cost of £51,000.27

George Murray accepted Holloway's proposal without demur and on 28

July 1845 it was forwarded to Lord Stanley for his approval. At that

time Murray made it clear that "This construction must be deemed to be

ultimately indefensible, however, against a combined military and naval

operation."28

The limited value of the works fully met the needs of the Colonial

Office. The decision to proceed without delay to their execution,

contingent on treasury approval, was communicated to the Master General

of the Ordnance on 15 August 1845.29 On 28 August this

decision was communicated to Holloway in Canada with orders to prepare

detailed submissions for the works30 for inclusion in the

next Ordnance estimates.

Up to this point agreement on the towers had proceeded in a regular,

if unusually expeditious manner, and construction normally would have

commenced in mid-1846 at the earliest. The continuing Anglo-American

diplomatic crisis, however, and the succession of Sir Richard Jackson,

the commander of the forces, by Cathcart as Governor General and

commander of the forces precipitated an early beginning. In December

1845 Cathcart feared that his whole force in Upper Canada might be

trapped by a sudden American assault on Kingston and ordered

construction of the approved works begun on his authority as commander

of the forces, rather than awaiting parliamentary approval.31

The urgency and extent of the works precluded their completion by

military artificers, and private tenders were called before the end of

1845.

On 28 January 1846 Cathcart approved bids for four towers from the

most reliable, though not the lowest, of the bidders. Immediate

construction costs were to be met from the military chest in

anticipation of parliamentary approval. The approved tenders totaled

£47,787.6.10½, distributed as follows: Murney Point tower,

£6,181; Cedar Island tower, £9,836; Market Shoal tower,

£6,885; Market Place battery, £9,013; and the Point

Frederick Fort and tower, £15,543.32

These figures were returned to the Inspector General of

Fortifications on 28 January 1846 and received his grudging acceptance,

although he had clearly not anticipated such an early start to the work.

John F. Burgoyne, the Inspector General, stated that "The collecting and

prepairing [sic] of materials, excavating foundations and

receiving tenders . . . would seem to imply a degree of preparation that

might preclude the use of any further consideration being given to the

projects."33 This was the case, and thereafter work

progressed with little overseas direction.

The four main harbour defence towers were indisputably Martello

towers, and, although freely adapted to meet local needs, all were of an

essentially similar design. While they were circular rather that ovoid

in their exterior form, Colonel Holloway reported in 1845, that they

would "follow the ordinary formation of towers."34 This was

particularly true of their internal structure and accoutrements. By the

time of their completion, however, the three land-based towers had

acquired a sophisticated caponiered flank defence and masking from

cannonade that must have rendered them among the most technologically

advanced of any Martello towers in the world. Certainly they had no

British North American peers.

Each of the towers was to be at least a two-storey structure with a

masonry exterior wall faced with ashlar limestone, rubble filling and a

brick-lined interior. They were to be between 50 and 65 ft. in exterior

diameter at the base and, with the exception of the 44-foot-high three

storey Fort Frederick tower, all were to have exterior walls between 33

and 38 ft. high. In each of the towers the circular interior compartment

was to be offset within the circular exterior wall giving an ovoid

appearance to their plans and providing a wall of unequal thickness

heavily biased toward the likely avenue of bombardment from the lake.

The approximate proportions of these walls varied from 9 to 15 ft. Each

tower was to be heavily arched in ashlar masonry above its barrack

level. The arch was to be sustained at the centre by a masonry pillar

and capped by an ashlar masonry terreplein. Each of the works was to be

adapted for heavy guns behind a masonry parapet. The barrack floors of

the towers were to be embrasured for carronades and the only entrance to

each was to be through a double reinforced door opening into the second,

or barrack, level of the tower. All were to be fitted with basement

magazines, cooking facilities, storage areas and pumps or cistern water

facilities to render each capable of independently supporting a garrison

through a long siege.35

From the outset each of the towers, with the exception of that to be

erected on the Market Shoal where external defences were impracticable,

was intended to be masked from the worst effects of naval gunfire and

protected from unimpeded infantry assault by provision of a ditch, stone

revetted counterscarp and glacis.36 This ditch, however,

provided no defence against an enemy established at the base of the

tower, and Colonel Holloway proposed to effect this necessary protection

by means of four mutually supporting loop-holed galleries or caponiers

attached to the base of each tower in preference to the more usual

machicolation galleries on the parapet. He included them in the

contractor's plans for the Murney, Point Frederick and Cedar Island

towers on his own initiative, as they would be completely hidden from

cannonade at any distance and so would well repay their cost of

£129 each.37 These precautions did not completely

shield the towers from gunfire though they were an improvement over

anything else in British North America.

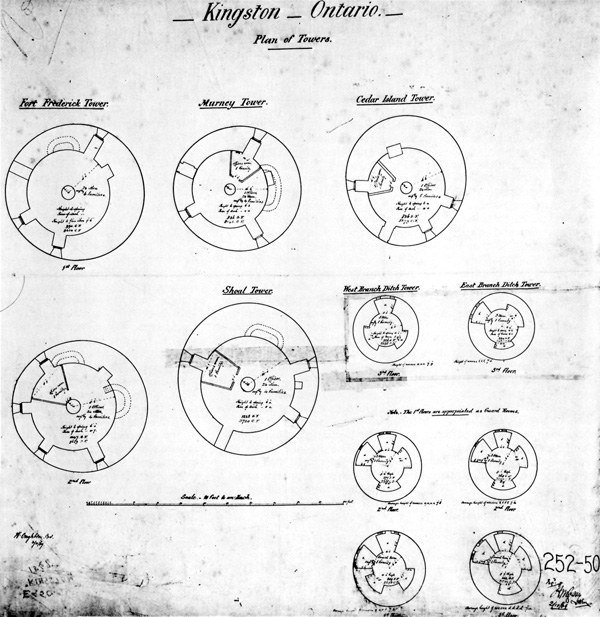

9 Barrack floor plans of the Kingston towers, 1869.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

10 Barrack level and platform plans of the Shoal, Murney and Cedar

Island towers, 1868, showing the quantity and location of the mounted

ordnance.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

The prior preparations. estimates and plans for the four Martello

towers were formally authorized as emergency defence construction by the

new Secretary of State for the Colonies, W. E. Gladstone, on 3 March

1846.38 When this was communicated to Canada, however, all of

the contracts had been issued for months and preparations for

construction were well in train. This was particularly true at the

accessible and conveniently located Murney Tower and the site of the

Shoal Tower. In the latter case, if construction were to commence in

1846, a coffer-dam had to be constructed on the ice, sunk on the shoal

as the ice melted, and pumped out to permit the workmen to build the

foundation.39 All of the towers were in preparation by the

end of March. It was at this time that names were fixed for them.

Colonel Holloway had proposed in February 1846 that each of the towers

be named after an official personage but the Inspector General of

Fortifications and the Master General of the Ordnance felt that naming

the works by locale would be more appropriate. Thus we have the names

Cedar Island, Murney and Shoal towers although the Canadian officials

persisted for some time in calling them respectively Cathcart Redoubt,

Murray Redoubt, and Victoria Tower. By June the Murney Tower was well

under construction, and by September 1846 all were reported in advanced.

condition.40 Despite this rapid early progress. work slowed

with the dissipation of the Oregon crisis after mid-1846, and by the end

of the year only the Murney Tower had been completed.41 Work

continued in 1847 and by September, Colonel Holloway could make the

following report on the towers:

Tower on Murney's Point 100% complete

Tower at Point Frederick 90% complete

Tower on Shoal in front of town 91% complete

Tower on Cedar Island 88% complete.42

In October he stated his expectation that most of the towers would be

completed by the end of the year: certainly all of them were ready for

arming early in 1848. The final detailed projected cost of each tower

was £10,251 for Cedar Island, £8,542 for Shoal Tower,

£6,856 for Murney Tower, and £7,442 for the one at Point

Frederick. All but that on the Market Shoal apparently included the

costs of counterscarps and glacis, and in total their cost was only

£2,944 in excess of the preliminary estimate of June

1845.43

Branch Ditch Towers

In addition to the four main Martello towers being erected at

Kingston in 1846 a functionally similar, but smaller and lighter, tower

was under construction at the lower extremity of each of the two branch

ditches that extended down the slope from Fort Henry to the water's edge

and isolated the end of the peninsula on which it was situated. These

towers were not directly related to the harbour defence programme and

were first suggested by Colonel Holloway in November 1845 to correct one

of the numerous technical defects of Fort Henry.44

The interiors of the branch ditches were not adequately flanked from

the fort and the steep and irregular drop from fort to shore left the

shoreline itself poorly defended against an assault landing. Defensible

guardhouses had earlier been approved for these locations. In late 1845

Holloway reported their substitution by the small towers at an estimated

cost of £6,262. They were to be of "hammer dressed masonry with

reverse fires looking into the ditch, the lower floor to be used as a

soldiers room for 20 men with single berths two tiers high, the walls to

be loop-holed . . . and a pintle for a traversing gun placed on

top."45 Burgoyne agreed with the substitution but advised

against placing the towers across the entire ditch saying, "but merely

add a tower there with a slight projection for flanking the ditch;

— the same tower being made also to flank the shore if possible

within and without, and be self-defensible."46

Accordingly the towers were cornered into the extremity of the ditch

with flanking embrasures and loopholes. A loopholed musketry gallery and

caponier, and the loopholed exterior face of the tower itself, were

directed toward the shore. These towers contained three interior storeys

and had a terreplein for one gun on top, behind a parapet. They were

both approximately 30 ft. in exterior diameter and 45 ft. high. The

exterior wall of each was 8 ft. thick on the water side where it might

be exposed to cannonade but reduced in places on the landward side to a

couple of feet. This was apparently to permit their easy reduction from

Fort Henry if they were captured during an attack and to allow the

easier working of their ordnance. These selective indentations gave a

very irregular appearance to the interior compartments of the towers.

Contemporary plans indicate that the towers were to have a single

elevated entrance door leading into the second floor of the tower on the

Fort Henry side, although at present there appears to be a ground-floor

door below the first in each case. Interior communication was by

hatchways and stairs or ladders. These towers had no central pillars and

the terreplein and dome arch were supported entirely by the exterior

wall.

The Branch Ditch towers had no magazines as they could be supplied

from Fort Henry. Originally, also, they had no barrack facilities as

they were not intended for permanent occupancy. Each of them was an

embrasured and top armed gun platform, functionally similar to the other

Kingston towers, but regarded as an appendage of Fort Henry. They

accorded it some small security but were not capable of a prolonged

resistance to an attack by land or water.

Structurally, they were in some ways similar to the standard British

one-gun tower, and to the one intended to be erected in advance of Fort

Henry in 1841. Certainly there was no shortage of contemporary plans

from which their form might have been adapted. They were the only

Canadian towers without central pillars. They were apparently begun

before the other Kingston towers, but were not completed until early

1848. At times work on them was stopped or delayed because of the more

urgent priorities of the main harbour defence towers.

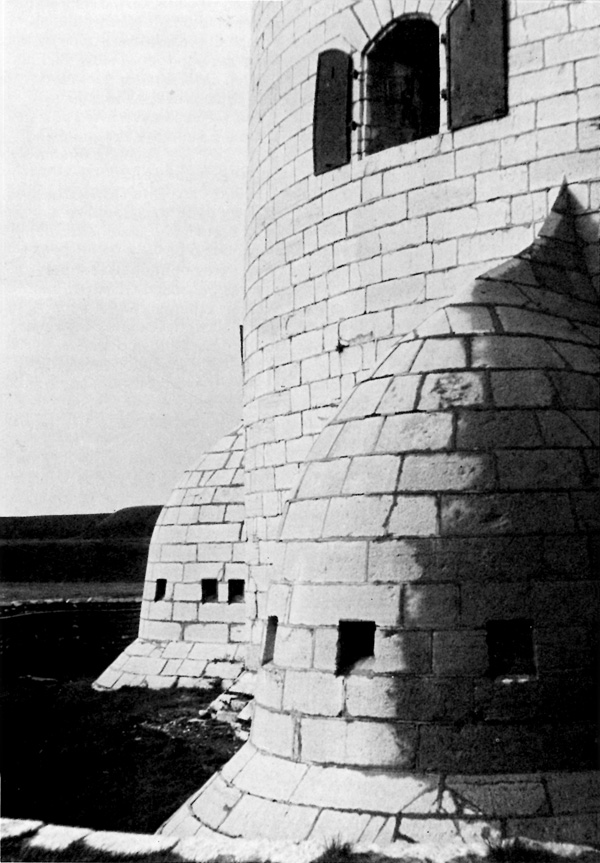

11 Photo of the base of the Fort Frederick tower, 1971, showing the

structure and position of caponiers in ditch.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Their subsequent history is in the same fashion subordinated to the

importance of the structural innovation. military merit and politics of

the construction and use of the other four towers.47 The

Branch Ditch towers were undertaken to meet a specific and limited need,

and contribute little to an understanding of the development and

deployment of this type of work.

All of the Murney, Point Frederick, Cedar Island and Shoal towers

were derived from the same pattern. When completed all had many similar

external features and were very much the same inside. The Murney Tower

was planned, commenced and completed before the others and contained

most of the salient features of the other three.

Murney Tower

The Murney Tower was constructed at a site on the western extremity

of the town of Kingston. Because of its great distance from Points Henry

and Frederick and the regular steamboat channel, it was never intended

to be more than an auxiliary to the lake defences. This early view of

the tower's role is substantiated by its intended meagre one-gun

armament.48 It was preliminarily estimated at £6,000

and the first plan, drawn in December 1845, differed only

insubstantially from the final design. The only noteworthy alteration

was the provision of the four caponiers and the consequent elimination

of the machicolation gallery over the door.49

In general form the tower was a two-storey masonry structure topped

by a terreplein and parapet. It was intended to be 56 ft. in exterior

diameter at the base with a slight inward taper to its 36-foot-high

scarp wall. The mean dimensions of the unequally proportioned exterior

wall were 14 ft. toward the lake and 8 ft. on the landward side. The two

interior levels of the tower were bombproofed above the barrack floor by

an ashlar masonry annular arch filled above with brick or rubble masonry

to the level of the ashlar platform. These gave it about 7 ft. of

bombproofing in all. This arch was sustained at the centre by a solid

masonry pillar 5 to 6 ft. in diameter extending down to the foundation.

The gun platform was some 6 ft. below the level of the crest of the

parapet with a double masonry banquette all round.

The exterior base of the tower was provided with four equally spaced

caponiers reached from the interior of the tower by passages through the

wall at its base. Each loopholed caponier extended out 13 ft. 6 in, from

the tower and the crest of its parabolic arch met the tower at a height

of 20 ft. above the foundation, at an angle precluding its use in

escalade. The bombproof caponier arch varied from 2 ft. 6 in. to 3 ft. 6

in. in thickness, and yielded an interior compartment 8 ft. x 10 ft. x 6

ft. 3 in. Each caponier was provided with 11 loopholes to enable it to

command the whole ditch in conjunction with its fellows.

At the Murney Point tower the ditch was intended to be 22 ft. wide on

the seaward side and 18 ft. on the landward side. The dry masonry

counterscarp, set at an angle of 75 degrees, was to be respectively 16

and 10 ft. high on those sides. The whole was to be provided with a

glacis to protect the counterscarp and almost completely hide the

caponiers. The barrack level entrance was originally intended to be

reached by a ladder of movable stairs from the bottom of the ditch. For

the sake of convenience, this was soon altered to a drawbridge over the

ditch.

The basement of the tower was reached by a hatchway and stairs

leading down through the wooden barrack level floor. The 9-foot-high

basement level was permanently partitioned in brick into storerooms and

a magazine leading off of a circular central passage around the pillar.

The 12 ft. x 14 ft. x 7 ft. magazine was arched in brick and had a

storage capacity of 114 barrels of powder when it entered service. The

magazine was provided with a small light chamber reached from the

central corridor and possessed a small shifting room at its entrance.

The other storage areas were intended to be given over to artillery.

equipment and provision stores. The caponiers were a poorly planned late

addition to the tower, and three of the four were reached through the

storerooms. These caponiers were separated from the interior of the

tower by a solid door at the interior end of the passage through the

wall and by an iron grille door at the outer end. The inner doors were

flanked on each side by a musketry loophole that afforded the defenders

a command of the grill-work door if a caponier were breached in an

attack. A brick-lined water tank 8 ft. square was created below the

basement level. It was to be supplied with water carried down from the

terreplein drainage system. It was intended to be drawn up again to the

barrack level by a pump for the use of the garrison in a siege.

The barrack area was 7 ft. high to the spring of the arch and of

about 14-ft. radius between pillar and wall. It contained the entrance

doorway, and the exterior wall was pierced at that level by three

embrasures for carronades. It was provided with a boiler arrangement

recessed into the wall for heating and cooking, and had two stoves, in

addition, for heating. All these were intended to vent, by means of

flues in the walls, to the crest of the parapet. For the most part this

floor was to remain an open barrack area, though a portion was

partitioned off to form an officers' room. Access to the top of the

tower was by means of a narrow stairway cut through the wide part of the

exterior wall from the barrack level to the parapet.

The terreplein of the Murney Tower was a regular circle, and was the

only one of the large Kingston towers so formed. The terrepleins of the

others were shaped in arcs to accommodate their intended ordnance. As

the Murney Tower was designed for only two pieces, it was possible for

both to traverse a full circle from a single pintle set at the centre of

the tower. The fronts of the traversing platforms of these pieces were

intended to ride on trucks resting on the banquette. The interior

seaward face of the parapet was provided with three shot recesses, and

the original contract plan of January 1846 envisioned the creation of a

passage for a machicolation over the entrance. The completed Murney

Tower was intended for a regular garrison of one officer or

non-commissioned officer and 24 men and capable of housing many more in

an emergency. It was in pattern the most sophisticated of all those

erected in Canada and was, in effect, a small self-contained

fortress.50

Fort Frederick Tower

A heavy earthen sea battery was also authorized for the extremity of

Point Frederick as part of the building programme of 1845. Its gorge was

to be defended by a loopholed masonry line wall and it was decided to

erect a Martello tower in the interior of the fort as a keep and barrack

for the whole position. The Point Frederick position was the chief focus

of the whole harbour and dockyard defence and was allocated

£20,000, over one-third of the whole emergency budget. The

necessity of accommodating a large garrison to man the battery led to

the construction of a three rather than the usual two-storey

tower.51

The Fort Frederick tower was circular in form and 60 ft. in exterior

diameter. Its slightly inward-sloping scarp wall was 45 ft. high from

its foundation to the crest of the parapet. The mean thicknesses of the

disproportionate exterior wall were about 15 and 9 ft. toward the lake

and land respectively. The wall was flanked at the base by four equally

spaced caponiers identical to those at Murney Point tower. In the

interior the solid circular central masonry pillar, 7 ft. in diameter in

the basement and diminishing to 6 ft. at the barrack levels, helped

sustain an annular ashlar masonry arch sprung over the second barrack

level. This approximately 3-foot-thick arch was filled above to the

level of the ashlar masonry terreplein and provided 6 ft. of vertical

bombproofing. The crest of the parapet extended 6 ft. above the level of

the terreplein and had a 2-foot-high banquette step at its base. The

only other external defensive feature of the tower was a shallow ditch

and counterscarp. As the tower was to an extent defended by the parapet

of the sea battery in front, it was not afforded the same level of

counterscarped defence as the Murney tower, thus permitting its musketry

fire as well as its embrasured carronades to sweep the whole interior of

the fort.

The tower's only outside entrance was by a door opening into the

second storey, and interior access to the basement was by stairs leading

down through the lower barrack floor. The basement, about 9 ft. high

with a 14-ft. radius, was partitioned off into an arched brick magazine,

magazine support facilities and storerooms leading off a narrow passage

around the pillar in much the same manner as at the Murney Point tower.

Its caponier entrances were similarly arranged and it likewise contained

a cistern below this floor level.

The lower barrack floor of the tower was intended to be retained as

an open room 10 ft. high with a 15-ft. radius from pillar to wall, all

round. Its floor was of wood and its ceiling was formed by the wooden

floor of the barrack level above. At this level the wall was pierced by

three carronade embrasures in addition to the doorway, and contained a

boiler heating arrangement recessed into the thickest portion of the

exterior wall. It communicated with the level above by stairs cut in the

outside wall. The upper barrack level was very similar to that below,

except that it was intended to have four carronade embrasures and its

ceiling was formed by the bombproof arch. It was about 15 ft. wide and 6

ft. high to the spring of the arch, which rose about another 4 ft. at

its centre. It also contained a recessed boiler for cooking and had an

officers' room partitioned off between pillar and wall. Another flight

of stairs within the outer wall of the tower led up to the terreplein.

This passage exited through the wall of the parapet at the top. The

tower was intended to mount three pieces of ordnance, and the terreplein

was accordingly shaped. The parapet was filled in concave arcs to

accommodate their traverses from separate centres in the English

fashion. The platforms were intended to pivot from pintles fixed in

their rear and traverse by means of trucks resting on the banquette.

Like the Murney tower, that at Point Frederick had three storage areas

recessed into the parapet.

While the base of the Fort Frederick tower was not as well defended

against artillery fire as that on Murney's Point, it was to be the most

heavily armed of all the Kingston Martello towers and when finished,

constituted an imposing battery keep. Through the medium of its platform

ordnance, it was also a well-protected small sea battery in its own

right. It was capable of firing over the parapet of the main battery

into Navy Bay and the commercial harbour and sweeping most of the

periphery of the low-lying point against an amphibious assault directed

at Fort Frederick.52

Cedar Island Tower

The first of the Kingston towers to be suggested and the last to be

completed was the one on Cedar Island. A tower in that location was

first recommended in Sherbrooke's 1816 fortification report, and

remained a constant of all subsequent defence schemes until the

authorization of its construction in August 1845. Its completion was

delayed into 1848 by the remoteness of its location and the need to

ferry the limestone building stone from the mainland. Cedar Island was

at the extreme east of the contemplated harbour defence and separated

from Point Henry by the entrance to Hamilton Cove. The cove was renamed

Deadman Bay after a number of workmen drowned there when a boat capsized

during the building of the tower. The tower was originally intended to

be located on the north end of the island to function as a sea battery

and prevent a landing in the cove. In 1845, however, Colonel Holloway

successfully argued for its relocation at the other end of the island

where it would be better placed for the general defence of the

harbour.53

The plans for the tower were drawn in March, and work commenced in

the summer of 1846 on a two-storey tower intended to be identical with

that on Murney's Point. The preliminary estimate was £6,000 but

unexpected construction problems raised its final projected cost to

£10,251.54

There were minor variations among the various plans but the completed

tower appears to have been 54 ft. in basal diameter and 36 ft. high from

the foundation to the crest of the parapet, with a disproportionate

exterior wall having a mean thickness of 8 ft. toward Fort Henry and 14

ft. on the opposite side. It was caponiered in the fashion of the Fort

Frederick and Murney towers. The first plans of March 1846 placed a

machicolation gallery above the second-floor entrance door on the Fort

Henry side, although the corrected plans of June of that year dispensed

with it.

The altered plans contemplated constructing a tower identical in

every internal feature with Murney Point tower and this would seem to be

very much the design finally carried into effect.55 The only

substantial variation between the two towers occurred on the top where

the Cedar Island tower followed the contoured plan of the Fort Frederick

tower, as it too was intended for three pieces of ordnance traversing

from separate centres.

While the tower itself was completed in 1848, its ditch and

counterscarp were not added immediately. The original intention had been

to surround the tower with a full ditch, counterscarp and glacis in the

manner of the Murney and Point Frederick towers. By August 1849,

however, this had been altered to a proposal for a partial redoubt that

would leave one side of the tower exposed to gunfire from Fort Henry.

This same proposal called for a musket gallery for reverse fire in the

counterscarp wall with a covered passage leading to a loopholed masonry

caponier set on the edge of the glacis beyond. A variation of this plan

was reintroduced in May 1850.56 Even without these external

defensive features the tower was an imposing, if isolated,

self-defensible sea battery for three heavy guns. The base of the tower

was 50 ft. above the waterline on the narrow island, and the tower

itself rose another 36 ft. above that level. While this height may have

hampered the effectiveness of its fire at very close range, it was well

adapted to commanding the passage into Hamilton Cove and cooperating

with the main harbour defences at long ranges.57

Shoal Tower

The last of the Kingston towers, the Shoal Tower, was a relatively

late entry into the scheme of Kingston's defences. Once suggested,

however, it was accorded a high local priority. Most of the earlier

defence schemes had contemplated defending the inner harbour with a

battery located at Mississauga Point on the western shore. By the time

of Colonel Holloway's report of 12 June 1845, that desirable position

was unavailable for fortification purposes. As an alternative, he

recommended forming a new nine-gun sea battery in front of the Market

House of the town. He further proposed that a tower for three pieces be

built on the shoal in front of the new battery. The two works he felt

would "fully effect the Command of the Harbour, with its channels and

anchorages, and support Fort Frederick in protecting the

dockyard."58 The harbour at that point was only about 700

yards wide. If it is remembered that, in addition to the above purposes,

the two works were to protect the Rideau Canal entrance, this seemingly

over-elaborate sea defence becomes much more comprehensible. In the

preliminary authorization of 15 August 1845, the tower was estimated at

£9,000 and, despite difficulties encountered in laying its

foundation, its final cost was only £8,725.59

Various methods of building a tower foundation on the shoal were

suggested and the engineer department finally adopted a proposal to

construct a coffer-dam on the ice and sink it onto the

shoal.60 It could then be pumped dry and the work commenced.

The coffer-dam contract was issued on 4 March 1846, the work completed

before the break-up of the ice, and the foundation commenced in the

spring of that year. This whole preliminary operation added the sum of

£1,196 to the cost of the tower.61

While the Shoal Tower is unique in its water location and in the

necessary coffer-dam, it was in most other ways an unexceptional

structure. From the outset it was intended to be a circular two-storey

masonry tower topped by a gun platform and parapet. It was the largest

of all the Kingston towers with a basal diameter of about 65 feet at the

high water line. The outward-sloping masonry foundation was 82 ft. wide

at the rock line 10 ft. below. The exterior wall of the tower rose some

35 ft. from the high-water line to the crest of the parapet. The mean

thickness of this wall was 14 ft. at its widest point toward the harbour

entrance. It declined to about 9 ft. on the opposite face. The tower had

a 3-foot-thick ashlar masonry annular arch sprung above its barrack

level. This was sustained by a regular solid circular pillar at the

centre of the usual proportions of 7 ft. diameter in the basement and 6

ft. on the barrack floor. This tower's shorter height, only 30 ft. from

the basement floor level to the crest of the parapet, necessitated a

compression of all its vertical dimensions. In consequence it had an

unusually shallow layer of additional bombproofing between the crown of

the arch and the terreplein. This was about one foot thick rather than

the usual three. Its parapet height was also a few inches lower than

normal. This same characteristic was carried to the interior where the

height of the basement was 8 ft. at maximum and the barrack level a mere

5 ft. to the spring of the arch. The Shoal Tower had a single doorway

opening into the barrack level through the thinnest portion of the

exterior wall. Communication to the basement was by the usual stairs.

The basement itself was circular and partitioned in the normal way into

storerooms and an arched brick magazine. This was not recessed into the

exterior wall and was somewhat smaller than usual, although the interior

diameter of the whole tower basement was slightly larger than was normal

at Kingston. The tower's location eliminated the need for a water

cistern. The barrack floor was a few feet larger than the average and

was otherwise undistinguished. It had three embrasures for carronades,

an officers' room, a recessed boiler for cooking and a stairway leading

off it up to the terreplein. The stairwell was cut through the thickest

part of the wall and exited through the side of the parapet above. The

terreplein and parapet were shaped in arcs to accommodate three pieces

of ordnance traversing from separate pivots after the fashion of the

Fort Frederick and Cedar Island towers. The parapet contained two shot

recesses and, in one plan, provision was made for

privies.62

The Shoal Tower's location precluded the necessity of any musketry

flank defence and it was left without caponiers, loopholes, or

machicoulis. Although it was ultimately susceptible to being reduced

from the western shore of the harbour, such a bombardment could not

occur until the town had already fallen. In point of situation it was,

with the Fort Frederick tower one of the two least vulnerable and most

advantageously located of all the Kingston towers.

All of the Kingston works authorized in 1845 were completed with

commendable speed and at the moderate cost of £53,944, exclusive

of the £6,262 voted for the Branch Ditch towers. The six towers,

however, contributed nothing material to the defences of Kingston for

over 14 years as, for a variety of reasons, they went unarmed for the

whole period. However well chosen their sites and whatever their

potential offensive and defensive military capacities, this fact weighs

heavily against the real military value of their construction. The

failure to arm the towers stemmed from no single conscious act of

policy, but from the relatively tranquil state of Anglo-American

relations between 1848 and 1861 and the underlying assumption that

preparing the towers for action would have been an act of no real

military consequence. The Martello towers were more neglected than the

other Kingston works in the 1850s but, because this inland terminus of

the Canadian defensive line was increasingly less defensible in the face

of growing American power, all the works were overlooked in the general

post-1850 revision of imperial and colonial defences that brought new

fortifications and armament proposals, and later works for Halifax and

Quebec.63

These Martello towers, of dubious tactical value when constructed,

began to decline immediately into a state of obsolescence that was

merely confirmed by the coming of the rifled gun and the massive display

of American military might after 1860. These weaknesses were further

articulated in the Jervois reports of 1864 and 1865.

Technically, the four main Kingston Martello towers were excellent

examples of their type. In their heavy construction, exploitation of

geography and use of ancillary defences against infantry and artillery

assault, they incorporated every practicable expedient that would make a

high-scarped masonry tower tenable in the face of attack. So anxious

were the authorities to test the value of the new towers that extensive

experiments were carried out at the representative Murney Tower as soon

as it was completed. In these trials the caponiers proved themselves

useful and efficient additions to the defence. As a flank defence the

Commanding Royal Engineer attested to "their superiority over any other

method that has hitherto come under my observation."64 The

ditches made an infantry attack a ponderous exercise and at breaching

distance the counterscarp and glacis almost totally obscured the tower,

leaving them subject only to mortar fire. So certain were the engineers

of the efficacy of the towers that Major Bonnycastle, the District

Commanding Engineer for Canada West, regretted: "We cannot fire at any

of the towers with heavy guns, as the direction that shot would take

after striking is uncertain, and might be attended with serious results

to the neighbouring buildings of the works or of the Town."65

It was also ascertained that an effective musket fire could be directed

on the glacis from the parapet. Colonel Holloway submitted to the

Inspector General of Fortifications that "The improved construction

appears to offer manifest advantages over the ordinary Martello tower,

particularly in isolated positions."66 However calculatedly

optimistic Holloway may have been, he was on the whole correct about a

group of towers that were the evolutionary end-product of a half-century

of experiment with that particular pattern of light permanent

fortification.

While the towers were not armed on completion, the four large ones

were almost immediately pressed into permanent barrack service. The

"green" masonry of their interiors was dried during 1848 and they were

fitted up for occupancy. In 1849 snow roofs of wood, covered with iron

to prevent fires, were added to protect the masonry. By the time they

were in place the main towers were already housing small numbers of men.

This barrack use, which continued in one form or other until after the

departure of the British garrison in 1870, is a distinction reserved

almost exclusively for the Kingston towers, as most of the others in

Canada were considered unsuitable for permanent occupancy.67

This same criticism applied at Kingston although it was not adhered to

there. As early as 1849 the staff surgeon condemned the Shoal Tower for

barrack purposes. In 1860 the Commanding Royal Engineer despaired of

making bombproof masonry works into healthy quarters. In 1864 another

engineer officer complained of the use of towers without lavatories,

ablution rooms, on any conveniences for the soldiers' comfort or

amusement, and recommended their occupancy be restricted to a guard in

wartime. After 1860, however, no change was thought desirable or

possible as the towers were in general use as married

quarters.68

While the towers continued to perform some useful service into the

1860s, neglect, lethargy and bureaucratic inefficiency combined to

prevent their effective arming until after the termination of the

Trent affair of 1861-62. The arming process commenced with a

short-lived controversy between the Commanding Royal Engineer and the

officer commanding the Royal Artillery. As early as August 1846, Colonel

Holloway, the engineer, recommended that the proposed towers not be

armed with the heavy 56-pounder or 8-inch shell guns lest they be taken

and turned against Fort Henry or the naval establishment. To prevent

this possibility, he proposed arming them with 24-pounder guns and light

howitzers. The officer commanding the artillery, on the other hand, was

anxious to extend the offensive power and range of the tower guns

against shipping and overrode the worst fears of Holloway's conservative

assessment. He proposed a compromise armament composed mainly of

32-pounder guns of 56 cwt. The balanced power, range and facility for

rapid fire of this version of the 32-pounder made it particularly

effective against distant shipping. At the same time he proposed

32-pounder carronades for the tower interiors so as to maintain a

uniformity of armament calibre.69

The decision rested with the artillery, and this 32-pounder ordnance

was ordered placed on the towers before the roofs were put on in 1849.

By 1850, seven 32-pounder guns were reported on the four main towers and

fourteen 32-pounder carronades within them. In addition there was a

32-pounder carronade on top of each of the Branch Ditch

towers.70 These were the guns and carronades that, for the

most part, later constituted the mounted ordnance of the towers, and on

the whole, it appears that they were judiciously chosen to meet the

particular geographical and other defensive peculiarities of

Kingston.

All the pieces were useless without proper carriages, and in

addition, the guns required fitted traversing platforms and racers to be

effective. The carronade carriages were not difficult to build and were

readily available from a quantity in store at Quebec. Serious problems

developed with the gun mountings, however: these had to be constructed

in England from drawings and adapted to meet the separate peculiarities

of each work. This practice was a general feature of preparing ordnance

for colonial works and while it may have produced a certain uniformity

of pattern and quality, it was at best a cumbersome procedure. In the

case of the Kingston Martello towers, all the difficulties were

aggravated by their unusual dimensions.

The towers had been commenced before common pattern platform plans

were accepted by the Royal Carriage Department in England, and the

engineers in Canada simply assumed that these plans would be altered to

suit the needs of the towers. The first plans were submitted home on

that basis. They were inaccurately drawn but, even when corrected

drawings were returned to England, the Royal Carriage Department

quibbled over the specifications as an excuse to avoid making the

necessary alterations in the platform pattern. No solution was reached

until early 1852, after a lengthy and involved dispute had occurred, and

then it was decided to alter the masonry of the towers rather than the

wooden gun platforms. Although the Master General was moved to pen some

caustic criticism of the lack of cooperation among the branches of the

Ordnance, this wasteful travesty on efficiency was not properly

corrected.71

Even this unsatisfactory resolution of the controversy did not

quickly produce the necessary traversing platforms, as British domestic

defence requirements took priority. They were not delivered in Kingston

until 1859, seven years after their authorization.72 In the

meantime little could be done to prepare the towers for the reception of

the traversing platforms and the little that was done was incorrect. The

pintles and racers prepared on the Fort Frederick and Cedar Island

towers were adapted for the ordinary, not the approved shorter dwarf,

platforms. The necessary subsequent alterations consumed more time, and

the tops of the Kingston towers were not finally armed until the second

half of 1862 after a further three-year delay. This delay was occasioned

by a shortage of the funds necessary to raise stone drums on the

terrepleins to suit the new traversing platforms, converting of the

works to the new style of raised racers, and then waiting for the new

hollow-soled platform trucks to fit the racers. The habit of

procrastination with regard to these towers was so deeply ingrained that

not even the Trent affair moved the authorities to hurry their

full preparation for war.73 It is difficult to believe that

the neglect and inefficiency chronicled above would have been allowed to

persist had the towers been deemed of any great value.

By November 1862, although some of the pieces were not yet in a

usable state,74 the towers were armed as follows:

|

| East Branch Ditch Tower | one 24-pdr. gun on top |

|

| West Branch Ditch Tower | one 24-pdr. gun on top |

|

| Fort Frederick Tower | two 32-pdr. guns on top

six 32-pdr. carronades within |

|

| Cedar Island Tower | two 32-pdr. guns on top

two 32-pdr. carronades within |

|

| Shoal Tower | two 32-pdr. guns on top

two 32-pdr. carronades within |

|

| Murney Tower | one 32-pdr. gun on top

two 32-pdr. carronades within.75 |

|

By February 1863 a third 32-pounder gun had been mounted on top of

each of the Fort Frederick, Cedar Island and Shoal towers, and by 1866

another 32-pounder carronade had been added to each of the last two

towers. The 24-pounder gun mounted on the Murney Point tower during the

Trent affair made a brief reappearance in the ordnance return for

that tower after 1863, but had disappeared by 1866. All of the guns on

top were mounted on dwarf traversing platforms moving on raised racers

and matching hollow-soled trucks. The carronades within were placed on

wooden ground platforms.76 The magazines of the four main

towers were supplied with small quantities of powder when they were

armed. Even though these towers were armed and equipped by 1863, it does

not appear that they could even be test-fired until the old wooden snow

roofs were replaced with more functional ones about 1867. The new snow

roofs were designed to be quickly and easily jettisoned into the ditch

in an emergency but it is difficult to see why. Such a procedure would

simply have blocked up the caponiers and provided an attacker with cover

and means of escalading the tower, as the ditches were not wide enough

for the roof segments to fall flat.77

Although the Kingston Martello towers were finally fully armed by

1863 some 14 years after their completion, any extended analysis of

their tactical merits becomes futile as by that date their military

obsolescence was generally recognized. As early as 1855 Colonel Ord's

report on the defence of Canada recognized the limited utility of the

towers and, in fact, of all the Kingston defences. While acknowledging

the necessity of an attacker's being well supplied with artillery to

breach them, he pointed out that their orientation to the harbour and

dockyard would necessitate their dependence on an effective field force

or a naval flotilla to resist an enemy in force on land. In both of

those instances the works would have been largely superfluous. Ord's

assessment was a polite expression of the fact that the towers were

useless against all but a hostile naval armada doggedly and

unimaginatively plodding in to force the harbour.78

Even this limited role was denied them in the somewhat later report

of Captain Noble, R. E., in which he pointed out that with the

introduction of the new rifled guns, with their longer range and greater

accuracy, the harbour and naval dockyard were vulnerable to bombardment

from as far out as Wolfe and Garden islands, beyond the range of the

towers' defensive 32-pounder smoothbore guns. Kingston was so vulnerable

that he recommended that the valuable naval stores be maintained afloat

above the Cataraqui bridge, beyond the range of the new

guns.79

It would appear that these towers only came to be armed at all

through reflex action and in the hope that they might form a

supplementary adjunct to an all-encompassing defensive system at some

future date.80 Such a system was suggested by Colonel Jervois

in his 1865 examination of Canadian defences, although he felt that

rifled ordnance would quickly silence the en barbette tower guns. He

went further to say that even in the days before rifled ordnance, the

towers could never have afforded efficient protection to the naval

establishment, even from a water-borne attack.81 Given the

dates of the towers' arming and the prior recognition of the

effectiveness of rifled guns, it is evident that these towers were not

considered capable of making a substantial contribution even to the

defence of Kingston harbour.

In 1845 the Kingston Martello towers provided a cheap, easy, and

obvious answer to a thorny and vexing defensive problem. They were

authorized and constructed to fulfil political, psychological and

financial rather than primarily military needs. It is indisputable that

Kingston required some sort of permanent protection at least to delay an

attacker, and that the towers built there embodied the most effective

and defensible design of such permanent works. However, as they were

geographically vulnerable from land and lake, they would have been

incapable of resisting the overwhelming tide of military and naval power

that could have been brought to bear against them by the industrializing

United States after 1848. The four large Kingston Martello towers were

in essence built to salve the conscience of a niggardly and

schizophrenic imperialism. All were the products of an era when old

colonial loyalties were breaking down and the British government was

seeking alternatives to the massive permanent fortifications which had

been such a dismal and costly failure.

|

|

|

|