|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 15

A History of Martello Towers in the Defence of British North America, 1796-1871

by Ivan J. Saunders

Stasis and Neglect: 1815-45

The history of Martello towers in British North America during the

30-year peace between 1815 and the Anglo-American Oregon crisis of 1845

is marked by two main themes: numerous proposals to build more towers

and neglect of the existing ones. Although throughout this whole period

none was commenced and only the Sherbrooke tower at Halifax was

completed, their frequent proposal is illustrative of the quandary of

the Colonial Office and British military strategists. The British found

themselves firmly committed to the defence of a vast developing inland

area where the range and expense of necessary fortifications was

magnified by every survey of the subject. They lacked the financial

means and, perhaps, any real desire to make thorough preparations for

war in an era of peace. In these circumstances they fell back on the

expedient of preparing many fortification proposals, building few works,

and for the most part trusting the defence of the British American

colonies to naval supremacy, successful diplomacy, and such scattered

existing works as had survived the earlier age of war. Martello towers,

because of their durability, were a major constituent of that defensive

pragmatism.

Although some of the existing towers were of questionable military

value and none had been put to the test of action before 1815, the

British government found it possible to maintain them in active service

during the three decades that followed because of the almost total

stasis in the development of ordnance and other offensive military

technology throughout that period. All eight of the towers completed by

1812 had been armed and prepared for action, and a number of them had

been garrisoned for the duration of the War of 1812. None of the towers

was deliberately disarmed with the coming of peace, but neither was the

Carleton Tower prepared for war. In every instance a process of

uncorrected deterioration and decay set in immediately on the towers.

This process was destructive of buildings, everywhere subject to heavy

frosts, and, in seaside locations, to the devastating effects of salt

air. The ongoing process of decay of the towers was almost everywhere

assisted by their on suitability as military barracks. Basically, they

were too cold and damp, and in some cases too remote, to be turned into

adequate permanent quarters. The consequent general lack of winter heat

accelerated the deterioration of the masonry while dampness rotted the

wooden fittings.

These natural processes were speeded up by the lethargy and

time-consuming administrative procedures that characterized the Ordnance

Department, which was exclusively charged with their overall maintenance

and carrying out even the most minor repairs on them. With the coming of

peace the abundant source of contingency funds, formerly available

through the military chest and at the disposal of the commander of the

forces, dried up. Thereafter, every repair item, even those as minor as

replacing window sashes and fixing door locks, had to be submitted to

England for approval of the Board of Ordnance and inclusion in the

Ordnance annual estimate for the following year. While this may have

been a sound and perhaps inevitable accounting procedure, it was

conducive to great delay and often, in that period of fiscal parsimony,

outright rejection year after year. Small tower repairs, such as broken

windows and shutters, were often not authorized until several years'

entry of moisture had badly rotted the interior woodwork. The whole

maintenance process was sometimes complicated further by the fact that

several military agencies shared partial responsibility for parts of the

tower. The engineers were charged with the task of overall repair of the

towers but the Royal Artillery, the other Board of Ordnance entity, was

responsible for the care of the ordnance and mountings and for the

magazine, if it contained powder. At the same time the Quartermaster

General's department, a part of the regular military establishment

reporting to the War Office, controlled the empty magazines and other

storage facilities. On the other hand the Barrack Department, another

Horse Guards' subsection, was in charge of the barrack levels of the

towers. The important chore of airing the towers in fine weather to

prevent mildew and rot appears to have been a much disputed and badly

performed joint responsibility of the Quartermaster and Barrack

departments. All of these separate and badly coordinated bodies were

under some measure of authority from the local military

commander.1 The consequence of this ponderous military

machinery was that the Martello towers, although they required little

repair and maintenance, received even less.

By about 1821 most of the gun powder and warlike stores had been

removed from the towers because of their lack of security and the

dampness of their poorly ventilated magazines. By that date, also, the

terreplein ordnance of the towers began to be dismounted and the

platforms and carriages stored within to preserve them from the worst

effects of the elements. Despite a local general order at Halifax in the

late 1820s to keep all the defences armed for immediate action, this

process continued until, by 1834, there was hardly a piece of mounted

ordnance on any of the towers in British North America. In 1821 only the

two 24-pounder guns remained mounted on the Prince of Wales Tower; at

Georges Island the tower retained only its four 24-pounder carronades on

top. The lack of a coordinated policy is illustrated by the fact that

the Carleton tower remained unarmed after 1815 while guns were mounted

on the Sherbrooke tower on its completion in 1828. At Quebec the only

pieces in place were the two 9-pounder guns within each of towers 2 and

3. This however, was not as serious a disadvantage as it might seem, as

most of the guns and carronades could be remounted in very short order,

although few towers were prepared to resist a surprise

attack.2

The deleterious effects of moisture on the artillery equipment and

the terreplein and parapet masonry of the towers, and of seepage within,

were diminished by the provision of conical snow roofs for all of the

towers after 1823. These roofs, supported by the tower either at its

centre or periphery, were generally so contrived as to permit some

limited firing of the guns while they were in place. They were, however,

intended to be removed in any serious crisis. The roofs of the Maritime

towers appear to have been cedar shingled while those on the Quebec

towers were later covered with sheet iron as fireproofing. The first use

of a shingled roof was on the partially completed Sherbrooke tower in

1818. This covering was perpetuated after its completion in 1827 by the

wood-roofed light room then erected upon it. A regular snow roof was

ordered for the Carleton tower in 1822 and for the Prince of Wales tower

by 1824 The Georges Island, Fort Clarence and Quebec towers were covered

about the same time. Only the York Redoubt tower was not provided with a

regulation snow roof: it did not require one, as its overhanging wooden

terreplein served to some extent to keep moisture off it. This de

facto roof, last replaced in 1809, was renewed about 1824 after

frequent complaints of its leaking.3

The York Redoubt and Sherbrooke towers were probably the best

maintained of all these early works. In the latter case this was due to

its regular occupancy by a lightkeeper after its completion, and in the

former, because it provided regular quarters for the men of the military

signal establishment operated from York Redoubt. This tower was a link

in the chain of signal stations down the harbour from Camperdown to

Citadel Hill.4 The most the others could hope for was the

irregular services of a caretaker.

While the masonry exterior walls of the towers were very enduring and

appear, in most cases, to have been repointed often enough to prevent

serious damage being done, a great problem had developed with the Quebec

towers as early as 1823. Their walls had been constructed with ashlar

masonry exterior facings over rubble or brickwork. By that date the

facings, which had been constructed without regular headers and

stretchers properly bedded, were so bulged in places that they appeared

ready to fall down. This problem was not immediately corrected and in

1826 it was reported that the towers

were built originally without a sufficient slope or batter, and

the rain having penetrated thro' the surface of the parapet, the severe

frosts and subsequent thaws of this climate have caused a good deal of

the outer stone work to peel off.5

This problem was subsequently corrected although at least one of the

Halifax towers was later allowed to deteriorate to a similar

extent.6

All of the completed towers appear to have run a slowly deteriorating

course until the new military crisis of 1845-46. At that time the

Ordnance reassessed their military condition and some of their guns and

carronades appear to have been remounted in anticipation of active

service. The Oregon crisis dissipated altogether too quickly, however,

to allow an excuse for their general repair, and by the late 1840s most

of them were still in an unimproved and unserviceable state, with

decayed gun carriages and floors and rotten door and window fittings

that exposed the interior to the elements.7 Although the

towers remained active components of the British defensive system after

1845, most of them were never refurbished or adapted to meet the new

conditions of warfare then emerging, and were accorded only such routine

maintenance as was necessary to maintain them while their ultimate fate

was decided by the War Office. It is difficult to assess the level of

unwarranted neglect of the towers in this period. To some extent their

original popularity had depended on their capacity to be shut up and

abandoned to await the next war. Most of them were certainly badly

maintained by a government preoccupied with massive fortifications but

none ever appears to have been completely unusable in an emergency.

While the existing Martello towers were perhaps being maintained in a

more slipshod manner than was intended even by the men who built them,

proposals for many others were being brought forward to meet the

defensive needs of the British North American provinces. This process

began immediately after the coming of peace in 1815 and was perpetuated

in the Smyth report of 1825 and the subsequent committees, commissions

and surveys that sought some manageable means of solving the dilemma of

British North American defence.

The first post-war Martello tower proposal came, not entirely

surprisingly, from Sir John Sherbrooke. Sherbrooke had been a devotee of

towers while in Halifax and by 1816 had been moved on to Canada to

become governor general. In July of that year he ordered a report on

Canadian fortifications. This document, forwarded to England in

December, recommended the construction of a number of towers at Kingston

to be used as battery keeps and outworks to the existing Fort Henry.

Sherbrooke's report was not implemented, but some of its themes were

taken up in 1818 by the Duke of Richmond, the Secretary for War, and

influenced the views of the Duke of Wellington, the newly appointed

Master General of Ordnance. Wellington in turn exerted a vital formative

influence on the deliberations of the Smyth Commission of

1825.8 This commission and the succeeding committees of

engineers which met over the next few years to refine the Smyth report

and determine the order of its implementation, together constitute the

most important departure in British North American strategic and

fortification thought in the first half of the 19th century.

The Smyth report and its proposed extended use of Martello towers was

antedated by a number of ad hoc local defensive proposals and

works, which were one of the contributory factors to the report being

commissioned. Among them were: the long mooted Quebec Citadel, which was

begun about 1820 to secure access to the Canadas: Fort Lennox on the

Richelieu, taken under consideration about the same time: the search for

a secure alternate water route from Montreal to the Great Lakes; and, in

the Maritimes, an 1824 proposal by James Arnold, the commanding Royal

Engineer, to construct a number of towers to defend the naval dockyard

at Halifax. The anticipated cost of such works helped precipitate Sir

James Carmichael Smyth's review of the overall defensive needs of the

colonies. Arnold's proposal serves as an example of the pressure for new

defences operating upon the British government. The cost of Arnold's

proposal was not stated but it must have been substantial. It was

essentially an amalgam of those earlier proposed by Fenwick, MacLauchlan

and Nicolls. Its key was the provision of two towers for Citadel Hill,

two towers for Needham's Hill and a line of towers across the

peninsula.

It also took cognizance of the earlier suggestions for a range of

towers on the Dartmouth side, although in view of General Mann's dictum

for economy and his predilection for confining permanent works to the

defence of the harbour, dockyard and town of Halifax, he did not press

the issue. Finally he urged the completion of the tower on Mauger

Beach.9 All of his suggestions except the last were stillborn

in the wake of the 1825 reassessment of British North American

defence.

Awakened to the prospect of some future military disaster and

prompted by the necessity of piecemeal and heavy future expenditures on

an antiquated defensive system largely neglected for a decade, the Duke

of Wellington, Master General of the Board of Ordnance, ordered a

thorough examination of existing and necessary defences of the British

North American provinces early in 1825. A commission of three under the

chairmanship of Major General Sir James Carmichael Smyth, R. E., toured

the provinces and made its report later that year. The commission found

most of the old works in ruins and determined that, although the Canadas

shared a 900-mile military frontier with the United States, the

Americans had only three worthwhile avenues of approach. These were by

the Richelieu route against Montreal and Quebec, across Lake Ontario to

Kingston, and against the Niagara frontier. Rather than reconstruct most

of the old scattered decayed works to meet an attack along these

avenues, the commission proposed an essential consolidation of the

garrisons within a few strongly fortified points strategically located

to check an American advance along the likely avenues of assault. In

conjunction with this strategy they proposed to leave much of the

intervening area to the command of a disposable field force. While the

commission found it could not recommend elimination of all the minor

points, it proposed defending them mainly with towers of one sort or

other. This whole defensive system was to be sustained by good water

communications withdrawn as far as possible from the American

frontier.

The strategy proposed by the commission was quite simple. It surmised

that, because of the opening up of the surrounding country, Fort Lennox

on the Richelieu could be by-passed. The members believed, however, that

with the defence of St. John's and Chambly, it would make the Richelieu

an untenable avenue of approach to Quebec, the final object of any

assault. Assuming that an enemy could be turned against Montreal first

they contemplated its defence by a citadel on Mont Royal supported by

outworks at the mouth of the Châteauguay River and Ile-Sainte-Hélène.

The commission generally favoured the use of large masonry barrack

towers costing £L50,000 each, like Fort Wellington near Ostend in

The Netherlands. Two of the works, however, were to be Martello towers

at a cost of £5,000 each.

At Kingston the Smyth Commission proposed to improve Fort Henry

greatly, repair the existing batteries and erect three Martello towers,

one on each of Cedar and Snake islands and one in advance of Fort Henry.

To the west of Kingston they proposed a major fortress on the Niagara

frontier sustained to the south and west by four redoubted Wellington

towers and three Martello towers. One of the latter was to be at the

mouth of the Thames River, and one at each end of Bois Blanc Island. At

Quebec the commission urged the completion of the citadel, which was

then only one-third finished, general improvement of the town works and

preparations for a defensive fieldwork line utilizing the Martello

towers, and a new Martello tower on the right bank of the Saint-Charles

River.

In the Maritimes, in essence, the commission proposed a road from

Rivière-du-Loup to Fredericton to facilitate communication between the

Canadas and Nova Scotia, a work at Fredericton on which to rally the

militia, a strong tower to reinforce a heavier battery at Partridge

Island, and erection of a citadel at Halifax and improvement of its sea

defences to prevent a coup de main. The suggested Halifax works

included completion of the Sherbrooke tower on Mauger Beach.

The whole projected cost of the commission's scheme, including the

Rideau Canal, the New Brunswick road and the fortifications, reached the

very high sum of £1,646,218. Although work soon commenced on the

canal, the Halifax Citadel and the casemated redoubt at Fort Henry, and

work on the Quebec Citadel pushed to completion, their financial

requirements exhausted most of the available funds. The remaining

proposals were refined and redefined over the next two decades, but

little or nothing was accomplished beyond the preparation of elaborate

plans and the completion of a few surveys.10

The Smyth Commission did not rely overmuch on Martello towers in the

new defensive system, preferring instead the more commodious and less

assailable Wellington towers. It did, however, appear freely to advocate

their use when necessary, and to favour them in circumstances where a

cheap, durable light permanent work was required to delay and hamper an

enemy briefly rather than to stop him for a protracted period.

Although a number of Martello towers were later erected at Kingston,

the only one of the many suggested in 1825 that was completed as

proposed was the Sherbrooke tower in Halifax. The commission suggested

that "as a further defence contributing equally to the Security of the

Harbour, and to impede any attempt at a 'coup de main' or surprise by

the North West Arm, that Sherbrooke's tower, commenced upon the Mauger

Rocks, should be completed."11 Another important impetus to

finish this Martello tower came in 1826 when the provincial legislature

voted £1,500 to erect a lighthouse on the beach. Gustavus Nicolls,

again Commanding Royal Engineer at Halifax, suggested that it would be

both necessary and inexpedient for the province to erect such a building

if the tower were completed. In such an instance the lighthouse would

effectively mask the fire of the tower. On the other hand, the tower was

too isolated to become a permanent barracks, and peacetime storage

facilities and accommodation for a lightkeeper could be supplied without

loss to the military.12 His suggestion was submitted to the

Board of Ordnance in June and received its approval in July 1826. The

tower, which was eight feet high at that point, was virtually complete

by November 1827, though the lighthouse was not in operation until April

1828. The intended platform armament of three 24-pounder guns was put in

place in 1827 before the wooden lighthouse superstructure was placed on

top of the tower. This light room caused almost no compromise in the

military design as it was balanced on a single masonry kingpost rising

from the centre of the platform. The umbrella effect of this arrangement

permitted the unrestricted traversing of the guns.13 Part of

the interior of the tower was given over to the purposes of the light.

The four 24-pounder carronades for the barrack level were not mounted.

although they were placed in the tower.14

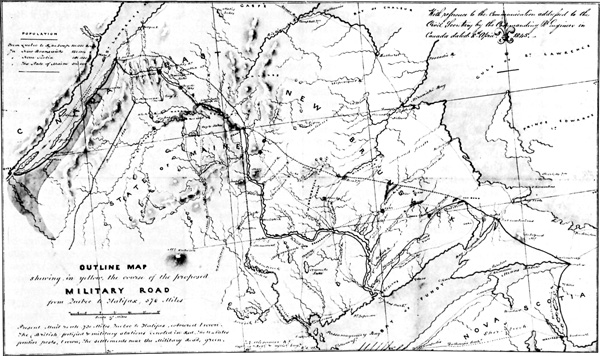

4 Map of the Province of New Brunswick, 1845, showing the course of the

proposed military road surveyed in that year.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

The fact that only the Sherbrooke tower was completed out of all

those recommended by the Smyth Commission did not prevent plans being

drawn for others of those proposed and the later projection of many

more. The first of these was the revised Partridge Island battery and

tower plan called for by the Inspector General's office in July 1826.

Captain Graydon, the Royal Engineer officer in New Brunswick, proposed a

heavy battery for each end of this small island at the entrance to Saint

John harbour. The batteries were to be enclosed by a continuous parapet

encompassing the whole upper part of the island. He was of the opinion

that such a work would make both harbour entrance channels impassable in

most circumstances. He further recommended a respectable tower midway

between the batteries to sweep them if they were taken by assault and to

serve as a bombproof barrack with storerooms sufficient to contain

supplies for a long siege. In its general features this proposed defence

was very similar to that of Georges Island. Both islands were difficult

of assault and offered an all-round perimeter defence of a position

primarily subject only to naval gunfire. This met the ideal conditions

for the employment of a Martello tower.

While neither tower nor batteries were constructed, a brief

examination of the tower's specifications and features allows an

assessment of the state of the tower building art in 1826. It was

intended to be a two-storey bombproof arched building with caponiers

communicating with each of the batteries. It was estimated that it would

cost £5,780. It was to be composed of one-third dressed masonry,

to be used in making the exterior of the wall, stairs, central pier and

the crest of the parapet. The remainder was to be of rough or rubble

masonry with brick arches and chimneys. Its woodwork and roof were to be

of spruce scantling with pine covering the floors. The same kind of wood

was to be used in the door and window fittings. The doors themselves

were to be of oak and the snow roof covered with cedar shingles. The

tower was to be heavily armed, with two 24-pounder guns on traversing

platforms and two 8-inch mortars on top and eight 24-pounder carronades

in the upper storey. This ordnance (including the only proposed use of

mortars on Canadian Martello towers), Graydon felt, would prevent an

enemy holding either battery if he should obtain it by a sudden

attack.15

The above proposal was hardly an isolated example. In 1827 Colonel

Nicolls recommended the construction of a number of towers. These

included several for the defence of St. John's, Newfoundland, and one

each for Needham's Hill in Halifax and Fort Edward, Windsor. The

detailed plan for the Needham's Hill tower was drawn and approved by

Major General Smyth. In New Brunswick two more towers were later

proposed for the defence of Saint John against a surprise attack. In

Canada plans were drawn for two 2-gun Martello towers, one for each end

of Bois Blanc Island. They were on the pattern of the one proposed for

Snake Island, Kingston. Although the Snake Island tower was never

constructed, there was a proliferation of the works proposed for

Kingston in the years 1825-29. The Smyth Commission recommendation had

been deemed inadequate for so important a point. By October 1829 a new

defence plan had been approved by the Board of Ordnance in an attempt to

provide an all-round defence by a system of works encompassing a new

Fort Henry, a series of redoubts and batteries and six Martello towers.

These towers were not constructed as planned due to a lack of funds and

the natural precedence of the main work at Fort Henry. While the towers

were not built they remained an integral component of the defensive

system and revised plans of some of them were ordered in 1839 and

1840.16 These persistent tower proposals emphasized the

assumed continuing military utility of Martello towers, both among

senior officers of the Board of Ordnance and engineer officers in

British North America, at a time when their general use was becoming the

subject of criticism in Great Britain.

The question remains, however, whether the espousal of towers was

primarily a military or political counter in the interminable debate on

British North American defences. The Duke of Wellington had delineated

the problem in March, 1819, while founding a hope of its solution on the

securing of an alternative means of inland communication further removed

from the American frontier than the St. Lawrence River. His dictum was

stated in the instructions to the Smyth Commission, in which it was

pointed out that:

It is quite obvious that if the Lines of communication proposed by

the Master General . . . for your consideration and report cannot be

carried into execution, or some other distinct from the St. Lawrence

discovered, the defence of those distant Provinces will become so

difficult as to be almost impossible.17

His views were reiterated in a letter to Lord Bathurst, the Secretary

for War, after receipt of the completed report at the end of 1825.

Arguing that British honour would prevent a withdrawal from Canada, he

gave it as his belief that if the communications line were built it

could be defended by means of fortifications. He further noted that if

the works were not constructed the loyalty of the populace would be lost

to the United States.

Even by the greatest exertion of the military resources of His

Majesty's Government in time of war, these dominions could not be

successfully and effectually defended, without the adoption of the

greatest part of the measures proposed; but if they are all adopted, and

attention is paid to the militia laws of these countries and care taken

to keep alive a military spirit among the population, the defence of

these Dominions ought not to be a more severe burden upon the military

resources of the empire in war, than such defence as was made proved to

be during the late war.18

None of these reviews challenged the essential defensibility of the

Maritime Provinces in the hands of the Royal Navy. By 1828 the defence

of the Canadas by a line of works and communications erected on a Quebec

City-Kingston-Short Hills-Lake Erie axis was firmly accepted into

British military orthodoxy and its prime essential, the Rideau Canal

system, was already under construction. In that year Major General Smyth

elaborated his views on the necessity of permanent fortifications and

established a rough equation between their completion and the number of

regular troops required for the defence of the country, and as well for

the effective use that could be made of the militia. He argued that the

substitution of a few judiciously placed and defensible works for the

many small posts formerly scattered along the frontier would provide

more effective rallying points for the militia. The locations for the

new works had been selected with this view in mind and Smyth felt it was

a very important one, as he placed small value on the militia in an

offensive capacity, although he felt it praiseworthy if used in a static

defensive role. By careful employment of the militia, primarily in

strong permanent works, he felt that the necessary wartime strength of

British regulars could be reduced to 5,000 infantry, a regiment of

cavalry and two brigades of field guns, in addition to the troops

required in the Maritimes. This he opposed to the currently estimated

necessary strength of 13,050. In Smyth's view his plan would ease the

sudden heavy manpower burden on the empire at war, effect a real economy

and improve the chance of success with works properly constructed in the

leisure of peace. Smyth certainly felt that permanency was the

overriding consideration and in 1827 he lamented how little of a

permanent nature had been accomplished at Halifax since Morse's report

to Sir Guy Carleton in 1783.19

Despite Smyth's cogent arguments for the construction of permanent

fortifications, the financial resources and sense of urgency necessary

to carry the system to completion were lacking. Work was initiated on a

continuing basis on the major fortresses at Halifax, Quebec and Kingston

but beyond that nothing of importance was actually completed before

1840, when Lord John Russell, the Colonial Secretary, ordered most of

the works contemplated by the commission of 1825 deferred for future

consideration.20

Russell's action appears to have been prompted by the fact that the

Smyth recommendations were by then 15 years out of date, and that the

effective and irreparable loss of naval supremacy on most of the Great

Lakes might have permanently altered the conditions and theatres of war

in British North America. By 1840 it was evident to Sir Richard Jackson

that the command even of Lake Ontario depended on the British capacity

to hold Kingston with its harbour and dockyard facilities.21

It appears that there might have been a general if unvoiced, suspicion

that nothing to the west of Kingston was permanently and assuredly

defensible in any event.

In 1840 Russell's doubts and the unsettled state of Anglo-American

relations produced a thoroughgoing reassessment of Canadian defences.

The opinions of officers in the British American provinces were

canvassed through the intermediary of the Governor General, and the

whole correspondence returned to Britain, it produced a reiteration of

the familiar arguments but yielded no definite general conclusions as to

the desirability or extent of permanent fortifications. On 18 February

1841, the Ordnance Office was moved to recommend that for the present,

at least, "It would be advisable to confine ourselves to carrying out

the fortifications at Kingston and Quebec, as proposed by the Inspector

General."22 Even this was not done to the full expected

extent and the resolution of the whole question awaited a pragmatic

solution induced by the appearance of another Anglo-American crisis.

The reports and memoranda of 1840-41 do, however, indicate that

Lieutenant Colonel Oldfield and his superiors in the Board of Ordnance

accorded a continuing and extensive role to Martello towers. In March

1840, Oldfield proposed that six round stone towers be built in a

half-circle in the rear of Montreal for its defence,23 and

plans for the defence of Ile-Sainte-Hélène by towers were being

forwarded to Britain as late as January 1847.24 Oldfield's

1840 survey of desirable fortifications was drawn up in reference to the

suggestions of the Smyth Commission of 1825 and included the tower for

the left bank of the Saint-Charles, first suggested in 1808; the six

Kingston towers recommended by the committee of 1829; a Martello tower

for Chippawa and two for Bois Blanc Island; another Martello tower as a

bastion keep for the fort at St. John's, Lower Canada; and numerous

other similar structures.25 While none of these towers was

ever constructed exactly as planned or suggested, and only the Kingston

towers were ever built at all, their continuing military acceptability

as a viable pattern of fortification is again clearly illustrated.

Further corroboration of the proposed use and continuing popularity

of round stone towers can be derived from Newfoundland, where, in 1841,

Sir John Harvey. the lieutenant governor, revived Gustavus Nicolls's

1827 suggestion and proposed a semi-circular series of eight such towers

for the land defence of St. John's harbour. His suggestion was rejected

out of hand from its unreasonable and unwarranted

expense.26

While factors contributing to the eventual construction of the

Kingston Martello towers can be discerned in almost every facet of the

long British North American defence controversy extending from 1816 to

1845, little of specific structural or functional consequence can be

ascertained from their often-suggested use, because none was commenced

and most were not even carried over into detailed plans. They were

projected in a wide variety of circumstances ranging from a keep to the

inaccessible sea batteries on Partridge Island to semicircular, mutually

supporting arcs of land defence in the rear of Montreal and St. John's,

Newfoundland. Their more common projected role, however, was as an

expedient means of defending exposed and isolated points, as at

Chippawa, "by posts, which although not calculated to withstand a

protracted siege, may be sufficiently respectable to oblige an enemy to

bring up his artillery, and thereby afford time for our troops and

militia to assemble for their support."27 Martello towers

with their high, thick scarp walls were ideally adapted to resist

surprise and escalade and to force their reduction by artillery. By

1846, Colonel Holloway, Oldfield's successor as commanding Royal

Engineer in Canada, was recommending towers almost to the exclusion of

all other works for defensible posts. By no means all of these were

round towers, for by 1840-41 square towers on the pattern of those

recommended for Lévis appear to have been recommended in about equal

proportion to Martello towers.28

The failure to build the towers proposed by the Smyth Commission is

easily explicable in terms of a commitment to large works, but the

failure to build any of those recommended in the general defence reports

of 1840 or after, despite their recognized value, is a more complex

problem. Economy and the future measure of the Anglo-Canadian colonial

relationship29 were contributing factors but for the most

part the lack of action was caused by the military confusion as to what

measures were likely to be effective and to repay the costs of

construction. In 1840 Sir Richard Jackson restated the obvious when he

lamented the advantage given to the Americans by the long unfavourable

line of the Canadian frontier and the American capacity to operate over

the ice in winter when no aid was possible from Great Britain. In this

way they could take possession of points necessary for future operations

before the opening of navigation. In consequence he recommended a

concentration of works at those points necessary to keep British options

open. Even this was difficult to determine, however, for by the 1840s

Canadian land communications had improved to the point that almost any

work, and certainly any of those west of Kingston, would be by-passed by

an enemy whose ultimate object was the fortress of Quebec. The British

government did attempt to implement a pallid version of Jackson's

proposals in the crisis year of 1845, but the authorized Kingston works

were inadequate, and the defence of the vital Montreal area was

relegated almost entirely to temporary fieldworks and a field force

operating to the south. Even this was done to protect communications via

the Rideau system, and to allow a naval contest on the Great Lakes,

rather than to hamper an invasion appreciably. As early as 1841 the

Board of Ordnance was rejecting works to resist an invasion because

there were too many holes in the line, and recommending that works be

confined to Quebec and Kingston.30

Despite the hasty authorization of a few works in 1845 the whole

temper of British North American defence in the years 1840-45 appears to

have been changing from a reliance on the principle of static defence

clearly enunciated by the committee of 1825, and further corroborated by

the later statements of Wellington and Smyth, to a reliance on a much

larger force of British regulars to be sent to Canada in an actual

emergency by means of an improved and defensible system of military

communications. From reasons both of necessity and expediency the

British government was returning to the 1812 principle of a reliance on

men rather than on fortifications.

Communications had certainly been well-considered in 1825, but by the

early 1840s the need to move large bodies of reinforcements inland the

year round lent the issue a new urgency. This requirement is marked by

the general survey of the Canadian water system, authorized in 1844 with

a view to its military and naval utility and because of the need to move

troops from Britain when the St. Lawrence was closed. It is also

indicated by the survey of the long mooted line of military road between

Halifax and Quebec ordered on 18 April 1845.31 This growing

concern with all-weather communication is further substantiated by the

survey and plan of a £70,000 fortress at Grand Falls, New

Brunswick, to protect this line although the government realized it was

likely to be little used. In the end both this fortress and the military

road failed to be implemented, with the dissolution of the Oregon crisis

in 1846 and the suspension of all further works in December of that

year.32

The year 1845 can be seen to mark the end of an era in the intended

general use of new and extensive permanent fortifications in the defense

of the interior of British North America, although this shift of

priorities did not apply to Quebec City or the sea defence works on the

Atlantic coast. Equally clearly, Martello towers were understood to be

an effective and integral component of the various systems of permanent

fortification articulated or approved between 1816 and 1845, and, in

fact, were among the very last of such permanent works built in the

Canadian interior.

The long history of the actual or intended use of Martello towers as

a viable pattern of fortification, as delineated above, was only made

possible by the lack of development of new instruments of offensive

warfare. While the problem of effectively attacking Martello towers in

the interior was often enhanced by the difficulty of moving artillery

over bad roads or by available water transport, their continued use in

positions accessible to naval or amphibious assault is reduced almost

totally to the technical difficulties of breaching them with

conventional smoothbore artillery from moderate range. This capacity of

the available ordnance changed only in small degree from the early years

of the 19th century until the introduction of rifled guns after 1860.

Most of the naval ordnance including the most common and effective 24-

and 32-pounder guns in British service in 1800, were still in use in

1860, although the 56- and 68-pounders and shell guns of various

calibres had been added. These last were of slightly longer range but

effected no revolutionary changes in breaching capacity.33 By

the 1850s the technical improvements and quantitative increase in

ordnance had led the British to consider the use of heavier earthworks

at Halifax and other places exposed to the full brunt of an attack, but

the subterranean masonry casemates that became a feature of the defences

erected against the rifled gun were not contemplated until the

1860s.

Isolated Martello towers in British North America appear often to

have been provided with a ditch and some measure of counterscarp, and of

course those within batteries were afforded some degree of masking

protection. Not until 1846 however, with the construction of three tower

redoubts at Kingston, was such a protective measure against artillery

deemed absolutely necessary. Even then only about one-half of the tower

was covered. The first redoubted towers were suggested by Gustavus

Nicolls for the Halifax peninsula in 1808, and tower 2 at Quebec had

been intended as a redoubted work. This proposal was reiterated in 1816

for all the Quebec towers, and in 1827 Nicolls gave it as his opinion

that all landward towers should be buttressed with

earthworks.34 Despite the apparent general agreement as to

the utility of this mode of improving the defensibility of Martello

towers, nothing was done about it.

Proposals for strongly counterscarped towers were revived in the

plans for those in advance of Fort Henry, Kingston, in

1839,35 and in 1840 Colonel Oldfield, the Commanding Royal

Engineer in Canada, again brought forward the earlier plan for

redoubting the Quebec towers. Because Quebec was indisputably the single

most important British North American defence point and because the

landlocked Martello towers constituted a significant portion of its

defensive outworks, an examination of the suggested mode of their

improvement provides a good measure of the techniques and funds

available to the engineer corps in updating such towers.

From the outset the role of the Quebec towers had been to impede an

assault against the main works, and this function was not diminished

with the completion of the Cape Diamond Citadel in 1830. At that time it

was intended to prepare and arm them for a 30-day siege.36 In

1840 Oldfield proposed expanding the Quebec outworks, although the four

towers on the Plains of Abraham were to remain the basis of the outer

line. He postulated a six-month siege of Quebec in which a tower line,

extending from tower 1 overlooking the St. Lawrence to the one to be

built on the right bank of the Saint-Charles River, would delay an enemy

two months. To make such a line tenable he proposed surrounding each of

the four existing towers with a strong earthen redoubt at a cost of

£1,244 each. His redoubts were to be composed of two faces and two

flanks defended at the gorge by a strong stockade. Each was to mount

three guns and contain a splinter-proof expense magazine, guardhouse,

and provision and coal store.37

Oldfield's idea was not accepted, and in 1841 he again submitted a

modified version of the same proposal. This time, from considerations of

expense, he contemplated redoubting only towers 2 and 3 and flanking

towers 1 and 4 with loopholed masonry walls. The Inspector General of

Fortifications sustained his view of the propriety of defending the

tower line while rejecting this particular proposal as inadequate. In

the end, the temper of the times and the fact that Quebec was already

the best defended point in Canada resulted in the strong redoubts never

being provided. Their construction was relegated to the never-never land

beyond the point where "the defenses of other parts of the province

shall be well advanced."38

The British failure to improve the defensive circumstances of the

Quebec towers, or any other of the existing British American Martello

towers, shows the clear unwillingness of the government to spend money

on such projects while at the same time indicating that no great

technologically inspired urgency surrounded the projects. Even the

theoretical designs of the engineers incorporated no additional

innovative protection that could not have been substituted for by

earthworks hastily thrown up in an emergency. Had time and the whims of

the enemy allowed such a course of emergency construction, it would

undoubtedly have been followed at each of the towers not already so

protected.

The course of the whole era of British North American defence between

1816 and 1845 is chiefly marked by a largely unsuccessful attempt on the

part of the imperial government to incorporate the negative lessons of

the War of 1812 into its thinking, and to discover some system of

defending the North American colonies with static permanent military

defences and secure lines of communication prepared in time of peace.

This process, revolutionary to a nation historically given to ignoring

fortifications in peace and financing their vast and frenzied temporary

proliferation in war, was ultimately defeated by the length and

vulnerability of the British North American frontier. In the end the

British government was forced to return more and more to the old mobile

defensive pattern in the great stretches of the country beyond the reach

of the guns of the Royal Navy.

This imperial experiment did, however, produce the Rideau Canal and,

at Halifax, Quebec and Kingston, fully establish an age of casemated

masonry fortification. In the restricted context of Martello towers,

little was accomplished by a government preoccupied with the size and

concentration of works, for the towers were essentially a product of a

time of more limited financial means and defensive requirements

demanding the impeding rather than the halting of an enemy force. Even

when the conditions of British American warfare were altered once more

by the limited willingness and capacity of the British treasury to meet

the ever-escalating demand for fortresses, a reliance on the efficacy of

field forces and improved communications prevented the reinstatement of

the pre-1815 role of Martello towers, except at Kingston. There they

were thrown up by an accident of geography and political expediency and

the final spasm of the military largesse of the British treasury in the

Canadian interior.

While no new Martello towers were commenced in the years 1816 to

1845, and by the latter date they were nearing the verge of military

obsolescence, their continuing local military popularity and versatility

was indicated by their frequent proposal to fulfill a wide variety of

military needs in much the same manner as they had between 1796 and

1815. Their persistent military utility is indisputable. This is evident

despite the fact that by 1827 the ten existing towers were being badly

neglected and allowed to decay below a point of immediate usefulness by

an ordnance corps and government preoccupied with the construction of

new works and caught up in the bureaucratic lethargy of the army in a

time of peace.

The allocated role of Martello towers remained essentially unaltered

through the three decades after 1815; but, with one largely accidental

respite, the death knell of the towers as respectable works was to be

inexorably rung in the following two decades.

|