|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 15

A History of Martello Towers in the Defence of British North America, 1796-1871

by Ivan J. Saunders

The Era of Great Construction: 1796-1815

Over half of the Martello towers ultimately erected in British North

America were constructed and armed in the short span of years between

1796 and 1815. This was also the period when they were most likely to

have seen use in combat. This figure includes, as is appropriate, the

first three Halifax towers, which were not strictly Martello towers. It

also encompasses the two later Halifax Martello towers, the four on the

Plains of Abraham in advance of the Quebec Citadel, and the one built on

the heights on the west side of Saint John, New Brunswick. In addition

to the multiplicity of towers actually commenced or completed at these

points, many more were projected for other places in British North

America in this period. when tower-building was seemingly contemplated

as an expedient for repairing almost every rent in the armour of the

defence of the British provinces.

Even at the conclusion of the long war with revolutionary and

Napoleonic France, the age of massive British North American defence

that culminated in the present citadels at Halifax and Quebec, the fort

at Ile-aux-Noix, and the heavy casemated redoubt of Fort Henry,

Kingston, remained for the future. In those years, however, there was a

qualitative change in the character of British American fortifications.

This trend led away from the temporary batteries, refurbished French

works and musket-proof wooden blockhouses that had marked previous

British attempts to ensure the loyal colonies against France and

America.

Both the means and the necessity for rationalizing the defence of

colonies thrusting a thousand miles into the interior awaited a more

propitious moment, but the year 1794 constitutes a benchmark in British

endeavours to lend an air of permanency to the defences of the more

salient points of the British American colonies. This process was often

obscured by the feverish temporary preparations to meet imminent attack

that characterized the early years of war, and was only imperfectly

articulated in the more measured responses of the later years. There is,

in this period, however, a discernible preference for building in

masonry where possible, and it was this penchant for permanence that

provided most of the impetus for the widespread use of Martello

towers.

At the onset of war in 1793, British North America was a relatively

minor constituent of an essentially European conflict, and the height of

the danger was the threat of a pillaging assault from the French navy on

the Atlantic coast. By 1807, however, after the blunting of the weight

of French sea-power at Trafalgar, the focus of danger had shifted

decisively to reveal an aggressive and antagonistic imperialism

established on the very frontiers of British North America. The hostile

appearance of the new United States and the likelihood of American

military aggression produced a fundamental alteration in the nature of

the requisite British military response in America.

The ten British North American Martello towers initiated before 1815

were primarily the result of a desire for permanent works and the

special problems posed by a prospective American war. Their final form,

number and locales, however were also influenced by the availability of

funds, geographical accident, and the personal predilections of

governors, commanders and engineers.

The building process began at Halifax, where three round stone

defensive towers were constructed between 1796 and 1799. These first

towers, erected before the design or even the name "Martello" had been

established in England, not surprisingly failed to conform in many

particulars to the structural definition imposed by later British

practice, although they were functionally similar to those in England

They do, however, display enough features of a common ancestry to merit

their inclusion in a general study of such towers. This decision is

reinforced by an analysis of alterations contemplated or actually

undertaken during the first 12 years of the towers' existence further to

adapt them to the general mold.

Halifax, founded in 1749, had served as a counterpoise to Louisbourg

and functioned as an offensive naval base and staging port until the

collapse of the French empire in America after 1759. The beginning of

the American Revolution in 1775 and the ensuing reversal of the

functional orientation of Halifax left its strategic role unaltered. The

resulting loss of the Thirteen Colonies in 1783 greatly enhanced its

value since it was now the preeminent strategic base for the defence of

Britain's truncated American empire, and it was launched on its long

history of service to the British fleet which constituted the only

permanently effective defence of British North America.

For a town and harbour of such enduring importance, Halifax was very

imperfectly defended in the 18th century against the threat of hostile

naval attack. With the collapse of the Indian danger after 1760, the

undeveloped and virtually impenetrable country beyond the town freed

Halifax from the threat of serious attack by land for decades, although

the danger from the French and later the embryonic American navies

remained unchanged. The first temporary Halifax sea defences were

erected in 1750. Although they were much expanded, they had achieved no

greater permanency when examined in detail in 1784, by Lieutenant

Colonel Morse of the Royal Engineers. All of the major works were

insubstantially composed of simple sods or fascines, haphazardly

situated and constructed, and, in Morse's opinion, collectively

incapable of preventing the passage of any enemy up the

harbour.1

The ineffectual and decaying Halifax works observed by Morse

continued to deteriorate through the decade of peace that followed.

Halifax's defences were largely ignored until the outbreak of war with

France in 1793. In the summer of that year, General Ogilvie, commander

of the forces in Nova Scotia, attempted to bring the old field works

into a defensible state and to expand the number of

batteries.2 Ogilvie's tenure was brief and his improvements

still incomplete when he was replaced by Edward, Duke of Kent, in

1794.

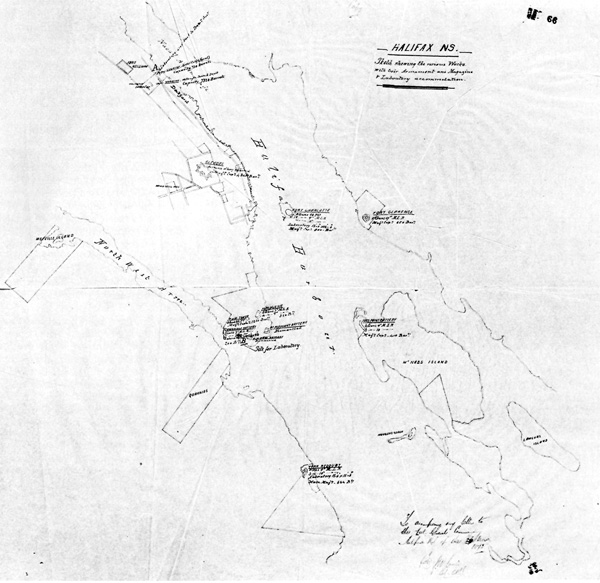

1 Plan of Halifax harbour and defences, 1875, showing works and

armament.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Edward, later the father of Queen Victoria and a wayward exile from

the court of his father, George III, was serving out his banishment in

military and other adventures in the colonies. Nonetheless, Edward was a

competent officer in many ways, and his arrival signaled a new era in

Halifax fortification. All previous Halifax works had been temporary

constructions designed to meet immediate emergencies. Though he was

bound by the same restrictive regulations as had hampered his

predecessors, Edward's personal enthusiasm for elaborate and durable

works and the influence of his rank allowed him to circumvent many of

those restrictions and, in his six-year tenure in Nova Scotia, to bring

the Halifax works to a level of permanency not achieved before, Edward's

ill-advised impetuosity soon necessitated the alteration of a number of

his efforts, but his penchant for building in masonry wherever possible

permanently altered the nature of fortification in Halifax.

The first demand on Edward's attention was the completion of

Ogilvie's work of putting the batteries in condition to meet an

anticipated French naval attack. By the end of 1794 this task had been

accomplished. It included upgrading the new Sandwich Point battery,

commenced by Ogilvie in 1793 and later renamed York Redoubt; partly

refurbishing the ruined Eastern Battery and Redoubt, later completed and

renamed Fort Clarence: and completing three sea batteries on Point

Pleasant, defending the harbour channel and the entrance to the

Northwest Arm. In his résumé of completed improvements and proposed

defences prepared in late 1794, Edward delineated all of the factors

that were to preoccupy and condition the defenders of Halifax for the

next seven decades. Among them, in addition to the major works he deemed

necessary for Citadel Hill, Georges Island and command of the anchoring

ground off Mauger's Beach, Edward noted the urgent necessity of

defending the rear of the exposed sea batteries on the eastern shore,

Sandwich Point, and Point Pleasant. These, he stated, would, with the

presence of the fleet, afford adequate security to the harbour.

Typically, Prince Edward, like his successors in the command of Halifax,

failed to acknowledge the vital role of the navy in any defence. Without

the navy the harbour remained virtually indefensible while with its

presence the sea batteries were largely superfluous. This enervating

view was not articulated and the new works proceeded apace.

By October 1796 Edward could report home that his projects for

Citadel Hill and Georges Island were well in train. At the same time he

announced that a two-storey blockhouse at the salient angle of the

stockade of the Sandwich Point battery was completed, that the battery

and redoubt on the Eastern Shore were finished except for a blockhouse

he proposed to have erected there in 1797, and that the recently

commenced stone tower in the rear of the Point Pleasant batteries was

already two-thirds completed.3

Prince of Wales Tower

This last remark referred to the structure now known as the "Prince

of Wales Martello tower." Although the completion of this work was

delayed until 1799 by a lengthy financial controversy, this speedy

beginning ensured the completion of a large two-storey masonry tower

capable of carrying up to ten pieces of ordnance on its flat

terreplein.4

While the European origins of the tower's design remain obscure, a

little is known of its adaptation to the height behind the Point

Pleasant batteries. Clearly it was not contemplated by Prince Edward in

1794, for at that time he specifically recommended defending the gorge

of each of the batteries by means of log guardhouses and palisades in

their immediate rear.5 By the spring of 1796, however, with

the whole military establishment caught in a wave of fear of the

imminent arrival of the French West Indies fleet off Halifax, Captain

Straton, the Commanding Royal Engineer, strongly recommended, and

Prince Edward quickly approved,

The erection of a stone tower to carry on the summit of it, four

sixty-eight pound carronades and two long twenty-four pounders, in a

situation not only most amply commanding the three Sea Batteries .

. . but also calculated greatly to annoy an enemy that might attempt

to land in the Northwest Arm.6

This tower, it was felt, would remove the danger that the three

batteries which constituted the principal sea defences of the western

side of the outer harbour might be eliminated by coup de main, by

compelling any assault force to reduce the tower some 400 yards in their

rear first. It would seem likely that this combined defence was little

more expensive and far more satisfactory than protecting each of the

batteries individually. A tower was chosen over the more conventional

earthwork, on the pragmatic grounds of speed and cost7

because:

Earth being extremely scarce on the spot judged fit for such a

work, and stone on the contrary being in great plenty, it was conceived

that a stone tower would be constructed with as little trouble as an

earthen work would have been.8

On technical grounds, the tower may also have been recommended

because of the security from sudden surprise and escalade provided by

its high scarp wall. This was much higher than could have been achieved

in an earthwork at similar cost.

Construction of the two-thirds completed tower was halted in November

1796 on the orders of the Secretary of State, the Duke of Portland, who

held that it was a permanent and not temporary fieldwork. Edward

therefore, was in violation of the 1791 regulations permitting a local

commander to undertake only temporary works in an emergency. The chief

difference in the two categories was that permanent works had to be

approved by Parliament under the authority of the separate Board of

Ordnance, while fieldworks were funded from the military chest on the

authority of the commander of the forces. The distinction, however, was

often a nebulous one, and in this instance Edward's personal power moved

Portland to intercede for ex post facto approval of the tower.

Portland was successful in June of 1797 and work resumed

thereafter.9 Most of the 1797 working season was lost because

of this dispute over Edward's authority and the circumstances of his

order for the tower. By the end of 1797, however, only the cutting and

placing of the coping stone for the merlons of the tower remained

undone. To that date the tower had cost only £1,137.15.9 although

a further estimate of £1,293 was then submitted for its

completion. Much of this sum was to be devoted to external fixtures such

as a ditch, counterscarp, glacis and palisade round the tower, although

£387 was earmarked for the merlons and a further £67

apportioned for internal partitions. Approval of this supplementary

estimate was communicated late in the 1798 season, and much of the work

remained for 1799.10 It would appear, however, that the tower

was functional and defensible in 1797.

The finished Prince of Wales Tower was an imposing structure, and, as

with many of the other Halifax works, Edward named it after a member of

the royal family in 1798. The tower was a circular rubble masonry

structure 72 ft. in exterior basal diameter and 26 ft. high from ground

level to the top of the parapet. Its slightly inward-sloping wall was 8

ft. thick at the bottom and 6 ft. at the parapet. The two interior

storeys were surmounted by a three-foot-thick timber roof, forming a

terreplein 60 ft. in diameter behind a six-foot-high parapet. This roof

was sustained at the centre by a hollow, circular, rubble masonry

interior wall extending down to the foundation of the tower. This wall,

concentric with the exterior face of the tower, created a central room

16 ft. in diameter on each of the levels in addition to the larger room,

16 ft. wide all round, formed between it and the exterior wall of the

tower.11 The exterior wall was pierced with 35 loopholes on

the ground floor as a means of musketry flank defence in addition to

eight loopholes on the upper level, which was also provided with four

embrasures for cannon. The parapet was pierced for 12 cannon embrasures;

the more functional barbette terreplein ordnance system was not adopted

in Halifax until some years later.12

The various early means of access to the tower remain a matter of

some dispute. It appears certain from a remark of Prince Edward's, in

which he referred to, "the bridge and Staircase to the top by which you

ascend to the tower on the outside," that a spiral staircase was one of

the first expedients. By 1812 a ground floor door had appeared. It could

have been created at any time after the inception of the tower and if it

were not one of the original features it may have well been opened at

the same time as the magazine, which appears to have been constructed

about 1805 and which was certainly present by 1810.13 The

typical second-storey Martello tower entrance door evident today was

only added as an afterthought in the 1860s and it appears the exterior

staircase had been removed by 1812.

With the external staircase, interior access must have been provided

by a hatchway in the terreplein, leading down by means of a ladder or

stairs to the upper interior storey which was used as a barrack.

Communication between the barrack room and the lower floor was provided

by a narrow stairway winding down through a passage in the exterior wall

of the tower near the site of the present ground-floor door. There may

also at that time have been hatches for stairs cut through the wooden

barrack floor. Lateral communication between the inner and outer rooms

on each level was by means of doorways cut through the interior masonry

wall.14

The permanent interior fittings of the tower were quite simple. On

the lower level they consisted of two cisterns sunk below the level of

the floor and, somewhat later, the small brick magazine partitioned off

in the outer room. The ground level loopholes were also served by a

wooden banquette around the wall. The basement floor was unheated while

the barrack floor above was provided with two fireplaces recessed in the

exterior wall and vented through it. Wooden partitioned officers' rooms

and berths for 96 men were added on this floor on completion of the

tower, but were soon removed to improve the air circulation

within.15

On the completion of the Prince of Wales Tower in 1799 there were

significant disparities evident between it and the common Martello tower

type. The most notable were its great overall diameter, the uniquely

large dimensions of its hollow central pillar and its lack of

bombproofing. It also lacked the typical means of access of such towers

and differed to the extent of having no magazine of its own. Neither

were its lower floor loopholes or embrasured parapet features of the

later structural definition of such towers. Over the succeeding 13 years

alterations were undertaken to some of the more changeable of these

deviations, bringing the Prince of Wales Tower into much closer

conformity to the then well-established functional pattern of Martello

towers.

The first of these changes came in 1805 with the addition of a badly

needed expense magazine with a capacity of 80 barrels of powder, while

the other changes remained for the major reconstruction approved by the

Board of Ordnance on 27 July 1810. These instructions gave permission to

throw a bombproof arch over the tower to protect it from plunging fire.

This was intended at the same time to end the complaints, which had been

a running feature of reports on the tower since 1803, that water was

leaking through the faulty wooden roof and destroying the interior. This

work was undertaken in 1811 and completed before the end of 1812; the

old wooden terreplein was removed and a heavy brick arch erected in its

stead. At the same time, the parapet embrasures were filled up so that

in future the ordnance would be mounted en barbette. Following these

alterations, terreplein access from the interior was by an aperture,

capped by a wooden cupola, cut through the centre of the new arch. This

was reached from below by a ladder or stairs leading from the central

room on the barrack floor of the tower.16 All these changes

did not make the Prince of Wales tower into a standard Martello tower,

but they did provide it with many functional similarities.

The armament of the Prince of Wales Tower was not quickly and

permanently established. It may have been armed before 1802, but by that

time it mounted four 6-pounder guns on its barrack level and two

24-pounder guns and four 68-pounder carronades on its top platform. The

heavy carronades were progressively removed between 1808 and 1810 and

replaced by a 24-pounder carronade after the alterations of 1811-12. By

1813 it mounted four 6-pounder guns on garrison carriages on its barrack

level, and two 24-pounder guns on traversing platforms and six

24-pounder carronades on traversing slides on top.17 The

nature and quality of this ordnance then remained unaltered for 50

years.

By the time its armament was stabilized, the tower had been fitted

with those military accoutrements that were to characterize its state of

preparedness through the War of 1812 and into the early years of the era

of peace that followed. It had been used as a supply house and provision

depot for the Point Pleasant position as early as 1805, and it appears

that the tower, which had an emergency capacity of 200 men, was shortly

thereafter provided with a store of arms and provisions for their use.

This amounted to 72 stands of arms, 12 pairs of pistols, and 30 boarding

pikes. Thirty-six barrels of powder had once been stored in the tower

magazine but had been injured by dampness, so by 1811 the powder was

kept in the nearby Point Pleasant magazine. The onset of an American

war, however, altered this arrangement once more, and 100 rounds for

each piece were stored in the tower in addition to the 10,000 musket

ball cartridges previously lodged there.18 With its other

fittings, the tower was thus equipped to withstand an extended

attack.

It appears that, despite the initial provision of barrack

accommodation and the retention of its heating and cooking facilities,

the Prince of Wales Tower was not regularly appropriated as a barrack.

This was the case, despite the lack of alternative accommodation on the

isolated point, as it proved too cold and damp for permanent use. In the

event of an attack, the tower, like the other smaller works, was

apparently to be manned by militiamen and by such regular gunners of

the navy and Royal Artillery as might be available.19 The

need never materialized and the tower remained a largely vacant sentinel

to the alarms of war.

The design and early history of the Prince of Wales Tower were

roughly paralleled in two other towers constructed at Halifax under the

direction of Prince Edward. Both of them were undoubtedly inspired by

the rapid progress and official popularity of the original tower.

However, each possessed characteristic features that made it more than

a poor imitation of the first Canadian tower. For the most part these

traits carried them farther than ever from the English model, although

modified versions of their most salient features were later to appear in

other Canadian Martello towers.

Fort Clarence Tower

The first of these towers to merit consideration is the Duke of

Clarence's Tower or Fort Clarence tower within the Fort Clarence Redoubt

on the east side of Halifax Harbour opposite Georges Island. This

position, known prior to 1798 as the Eastern Battery, was first occupied

in 1754 when a battery of guns was placed there to co-operate with

Georges Island in defending the 1,500-yard-wide eastern passage. This

battery was commanded from rising ground a few hundred yards in its rear

and subsequently an oblong earthen redoubt was erected behind it to

assist in its defence.

By 1784 both battery and redoubt were in a ruinous state and they

continued to deteriorate for another decade. Prince Edward renovated the

position after 1794, and in 1796 pronounced it complete, except for the

addition of a blockhouse in the interior of the redoubt which he

proposed adding in 1797. This blockhouse was not added because Edward

soon decided to substitute a round tower for it. The building materials

for the tower were already gathered by April 1798, when Captain Straton,

the Commanding Royal Engineer, announced his opposition to its

construction. Straton urged that the whole work should be abandoned as

it was defective in a manner not rectifiable by a tower keep as the

redoubt itself was commanded from above. He suggested that the tower

materials be moved and used to form a battery keep in a more secure

location on McNab Island. Edward persisted, however, and the masonry of

the tower was completed by October 1798, although the external stair had

not been placed nor the parapet coping provided as late as

1803.20 Thus this tower was erected, seemingly on Edward's

whim and against the advice of his engineer officer, in a location

effectively commanded at 300-500 yards distance.

Despite its seemingly dubious military virtues, the tower's enduring

role in an important harbour position render its structural and

defensive features worthy of some consideration. The tower was 50 ft. in

exterior basal diameter and 42 ft. high from foundation to parapet, with

an exterior sandstone masonry wall uniformly 6 ft. thick. Because of the

need to provide emergency accommodation for the whole garrison of the

isolated Fort Clarence, it had three rather than the usual two storeys.

The whole was capped by an unbombproofed terreplein composed of two feet

of layered timber topped by 112 ft. of plaster of paris surrounded by an

embrasured parapet. The terreplein and interior floors were supported by

a thin-walled hollow central pillar concentric with the exterior wall,

extending from top level to ground and forming a small central room some

6 ft. in diameter. This was suitable for communication or for hoisting

ammunition to the top of the tower, and was probably employed for that

purpose.

In spite of the tower's 42 ft. height, it would have appeared no

taller than other towers from a distance because a full 8 ft. of this

height were hidden by a seven-foot-wide ditch surrounding the tower.

This ditch was spanned by two loopholed caponiers on opposite sides of

the tower. They provided both a flanking fire at its base and a secure

communication to the timber-roofed subterranean magazine and cookhouse

that flanked the tower on either side beyond the ditch. The tower was

not intended as a permanent barrack and the external fixtures above

enumerated, along with an excellent well, must virtually have eliminated

the need for internal barrack fittings. There are, however, later

indications of a fireplace and of the internal partitioning of the lower

level for emergency use.21 The wall of each of the three

interior storeys was pierced by loopholes for musketry and each of the

upper and lower barrack floors above the basement was provided with four

embrasures for cannon. The parapet on top was pierced with eight

embrasures for guns or carronades.22 The completed tower had

only one intended means of access, an external iron staircase to the

top.23 It is not known where on the terreplein the hatch

leading inside was located, nor what means were used in internal

communication. The Duke of Clarence's Tower was not as strong a work as

that on Point Pleasant, but its position within the fort may have made

such strength seem unnecessary.

The completed Fort Clarence tower conformed fairly closely to the

Martello tower pattern in some ways, but there were disparities in

height and in the nature of its internal pillar, its lack of

bombproofing, lower floor loopholing, mode of access and embrasured

parapet. Its most interesting feature was its caponiers. In possessing

these it was unique among the British North American towers until a

variation of this feature was adopted at Kingston 48 years later.

The tower underwent alterations in the 14 years following its nominal

completion, although they were of less consequence than those undertaken

at the Prince of Wales Tower. The long neglected external stairway was

finally put in place, although in 1812 it was removed and replaced by a

door at ground level leading into the second storey of the tower. This

door was reached by a drawbridge across the ditch. In the same year a

small brick magazine of 100-barrel capacity was constructed within the

tower, as the subterranean one nearby was badly decayed. The

unbombproofed terreplein had been a frequent cause of engineer

complaints, but in 1812 it was replaced by another timber roof. This

failure to improve the tower top's defensibility against high-angled

fire may have resulted from the inability of the thin central pillar to

sustain the weight of an arch. Another alteration carried forth at the

same time was filling the parapet embrasures on the landward side and

cutting the parapet down to 3 ft. toward the water, so as to retain the

protection in the potentially threatened rear while converting it into a

barbette work on its less exposed seaward face.24 These

alterations were undertaken to bring the tower into closer conformity

with its military environment, and they much improved its potential

defensibility in the war that soon occurred.

The Duke of Clarence's Tower had been built to mount up to 16 pieces

of ordnance in all. It was probably armed about 1805, but no tabulation

of its mounted ordnance appears prior to March 1808. The tower was a

battery keep rather than an offensive sea battery, and was always armed

accordingly. It had carronades and howitzers in preference to guns of

longer range. In 1808 it contained 12 pieces: four 32-pounders and four

24-pounder carronades on top and four antiquated 8-inch brass howitzers

mounted within. By July 1810, two of the howitzers had been removed, and

by 1812 all of them had been replaced by four 24-pounder carronades

mounted on the barrack level on wooden carriages. In 1812 the top

armament of the tower consisted of eight 24-pounder carronades on

traversing slides mounted en barbette.25 This armament gave

it a ferocious firepower at short range, but denied it a larger

role.

All of the tower's defensive equipment was installed by 1812 and was

never subsequently upgraded. The barrack floors of the tower were fitted

for arms storage, and by 1808 contained 200 muskets, a proportion of

pistols and pikes, and 20,000 musket cartridges for the use of the

defenders. This equipment, with the addition of 100 rounds of powder and

shot for each piece, remained in place for some years.26 The

tower was not deemed fit for barrack accommodation, and by 1812

alternative quarters had been prepared for the small regular garrison of

the work.

The tower was intended to be defended by up to 164 men, who were to

be drawn from a company of volunteer artillery on the Dartmouth side,

bolstered by a leaven of the Royal Artillery stationed in

Halifax.27 This tower suffered from two great weaknesses: its

location below and in front of the commanding height and its

vulnerability to mortar fire. Despite its use as a battery keep in the

manner recommended by Colonel Twiss and other influential engineer

officers, it is perhaps fortunate that its defensive merits were never

tested from the land.

York Redoubt Tower

Edward's other Halifax tower was also an innovative structure and is

likewise difficult to classify as a Martello tower. This was the Duke of

York's Tower in York Redoubt. This so-called "redoubt" was a sea battery

located on a high bluff overlooking the outer harbour channel from its

western side. Ogilvie had opened a battery there in 1793, and Edward

further upgraded and stockaded the position between 1794 and 1796. By

the latter year he had also added a wooden blockhouse to the salient

angle of the palisade in the rear of the eight-gun battery and at that

time he reported the position complete. He soon reconsidered, however,

and by 1798 had removed the new blockhouse and replaced it with a round

masonry tower of rough quarried stone. His rationale is uncertain,

though the blockhouse may not have provided the desired security or

carried the weight of ordnance deemed necessary in its isolated

location. The whole redoubt remained a very weak one, mainly dependent

for its security on the freedom from naval bombardment provided by its

great height above sea level, and from an artillery assault in its rear

by the rough and inaccessible nature of the land.

The finished two-storey tower was 40 ft. in exterior diameter at the

base and 30 ft. high to the level of the terreplein. Its walls were

uniformly about 4 ft. thick. The tower had a thin-walled hollow circular

central pillar similar to that of the Fort Clarence tower that extended

its entire height. The interior space thus created was likewise suitable

for hoisting ammunition or for the placement of a communicating

staircase.28

The flat terreplein of this tower was of wooden construction as

favoured by Edward and Straton. It was, however, unique among Canadian

towers in that its circular parapet was constructed of the same

material. This expedient was dictated by the need for the rapid

completion of the tower rather than by the conscious design of its

builders.29 The first wooden superstructure appears to have

been formed by simply laying the terreplein timber on top of the

exterior masonry wall and extending it four feet beyond the edge all

round. The four-foot-high musket-proof wooden epaulement was then

attached around the extremity of the terreplein. A de facto

machicolation gallery was thus created all round the tower, as a

plunging fire could be brought to bear on the base of the tower from

holes cut in the projecting portion of the terreplein. The parapet wall

was loopholed for musketry and embrasured for cannon. This top defence

was supplemented by embrasures, and probably by loopholes, on the

barrack level immediately below.

Once again the nature and extent of the entrances to the tower are

difficult to determine. It is known that entrance to the tower was later

achieved by an outside staircase to the top, and, given the examples of

the Prince of Wales and Clarence towers, this was probably the original

means of access. This was later supplemented by a barrack-level entrance

reached by a drawbridge over a ditch from the exterior of the work and

by a ground-floor entrance door. The original means of internal

communication is uncertain, although later the space within the central

pillar was appropriated for this purpose. The first terreplein entrance

hatch was probably also at this point.30

The Duke of York's Tower appears to have been provided with its own

small bombproof brick magazine after 1811. Otherwise its main military

features remained unaltered for several decades, as it missed the flurry

of alteration just prior to the War of 1812. Despite Captain Fenwick's

early allusions to the weakness of the wooden parapet and terreplein,

Lieutenant MacLauchlan, his successor, who appears not to have been very

competent, declined to renew them in masonry. MacLauchlan commented that

the local building stone was so "weak, bad and expensive" that such an

endeavour would not be worth the effort. Consequently the old roof was

replaced by another one of wood in 1809, and nothing else of substance

was altered until the 1860s.31

Probably the tower was armed before 1808, although its first ordnance

return dates from that year. At that time it mounted two 6-pounder guns

in the interior embrasures and two 12-pounder and two 24-pounder

carronades at the embrasures on top. By 1810 the top ordnance had been

altered to six 12-pounder carronades, at which level it was to be

maintained. The heavy carronades were apparently removed without qualms,

perhaps because several smaller pieces were more desirable in a position

whose main danger arose from an infantry assault. This trend to more

pieces of smaller calibre was general among the three towers. By 1812 it

had also been provided with 111 muskets, pistols and pikes, and 10,000

ball cartridges.32 Afterwards its armament remained unchanged

for 50 years.

This tower was in fairly constant use for barrack purposes. It was

occupied as early as 1800, though it contained no adequate regular

barrack facilities. Its small garrison fluctuated from a few privates

and a non-commissioned officer to eight Royal Artillery gunners in the

1800-15 period.33 Their primary function was to raise the

alarm and man the guns in case of attack, as the redoubt was the first

harbour position to take up an approaching fleet. In the absence of an

enemy, however, theirs was largely a caretaker role over the arms and

facilities of the isolated position. They may also, from the outset,

have performed the signalling function that was to keep the tower in use

for many years. In a real emergency this small force was to be

supplemented by up to 100 militiamen lodged in the tower.

It can be seen that the Duke of York's Tower was the most primitive

of the three Edward had constructed in Halifax. In many ways it

resembled the other two but its most salient feature was the

accidentally created machicolation gallery, making it more reminiscent

of a frontier blockhouse than a bomb-proofed masonry Martello tower.

Despite its structural inadequacies, it was not badly adapted to the

requirements of its almost inaccessible position, and when armed and

prepared for war it was undoubtedly the strongest feature of the weak

redoubt, not only at that time but until the 1860s.

Prince Edward left Halifax in 1800 soon after the completion of his

three stone towers. Despite their common overall structural pattern it

is evident that none was a Martello tower in a narrow sense, their

divergent origins being displayed most particularly in their hollow

pillars, mode of access and lack of bombproofing. All were adapted to

rectify defects of design and meet anticipated future military needs in

the years before the War of 1812. In the case of the Prince of Wales

Tower, these changes brought it closer to a definition of a Martello

tower, but all the work was undertaken more to bring the towers into

conformity with purely local defensive needs than from a deliberate

desire to turn them into regulation Martello towers. While the towers

were apparently adequate for those needs after they were properly armed

and equipped, they were on the whole an evolutionary dead-end not copied

elsewhere in British North America.

While Edward's towers were not copied, their completion by no means

exhausted the popularity of round stone towers in the Halifax area. In

1801, Captain William Fenwick, the Commanding Royal Engineer, who was

generally a severe critic of Edward's works, proposed three massive

masonry towers, two to defend the extremities of the Citadel Hill work

and another to command the dead ground below the Georges Island star

fort. These works were large and elaborate caponiered towers 78 feet

high and 50 feet in diameter, and, at £9,600 each, so costly that

the proposal was quickly dismissed.34

These and Edward's earlier proposals had been designed to meet the

threat of French naval attack, but by the end of 1807 a new danger of

hostilities with the United States had emerged. At that time

MacLauchlan, the engineer, proposed a round tower to occupy a height to

the north of Needham's Hill on the Halifax peninsula. The work was

approved under the authority of the local commander of the forces, but

the lateness of the season for masonry work forced the substitution of a

musket-proof blockhouse. War preparations continued into the spring of

1808, and a number of Martello tower proposals were put forward, chiefly

at the instigation of Captain Gustavus Nicolls who had replaced

MacLauchlan as commanding Royal Engineer in Nova Scotia.

Captain Nicolls' proposals were prompted by the virtual

indefensibility of the town, harbour and dockyard, and were seconded by

Major General Martin Hunter and Sir George Prevost, successive

commanders of the forces in Halifax. Nicolls adopted MacLauchlan's plan

for erecting towers on the hills to the east of Halifax in the rear of

Fort Clarence,35 and General Hunter said of this

proposal:

It is the opinion of the Chief Engineer here, in which I perfectly

agree with him, that on the Dartmouth side of the harbour of Halifax,

where there is only one Martello Tower that three more could be placed

to great use, indeed I think absolutely necessary for the protection of

the Dock yard and Town.36

The general's comment constituted the first explicit Canadian

recognition of Martello towers, for Edward's towers were not known by

that name. It achieved little else since a shortage of building

materials prevented construction of the Dartmouth towers.

Nicolls further proposed three more towers, mutually supporting and

for 120 men and 4 pieces each, to shut off the entrance to the Halifax

peninsula. Lastly, he recommended that a Martello tower be constructed

within Fort Needham to command the adjacent ground. He defended his

choices by saying:

I consider the construction of the towers . . . would constitute

the cheapest, most permanent, and most effectual defence; at the same

time requiring the smallest number of men.37

Captain Nicolls' scheme was still born with the declining likelihood

of an Anglo-American war. Its most enduring virtue rests in the insight

it provides on the colonial popularity and attractions of the new

Martello towers. Nicolls was a competent and intelligent officer who

later achieved high rank in his corps. He approved the towers primarily

because they were cheap and could be completed in a single season,

providing both emergency protection and fortifications of enduring

value.38 They must also have seemed a god-send in a climate

where hard frosts could destroy laboriously constructed earthworks in a

single season.

Nicolls' proposal also indicates an early and basic adaptation in the

use of such towers. He may not have been intimately aware of the British

principles of locating these works, construction of which had only

recently begun. He proposed shielding some of his towers behind ditch,

glacis and counterscarp, but his plan violated the prevailing orthodoxy

and the almost universal custom at home of not generally building the

towers in inland locations where they would be exposed to fire from

land-based artillery. It was the generally, and perhaps accurately,

accepted view that they would be breached quickly in such

circumstances.

Quebec Martello Towers

Gustavus Nicolls's tactical heresy at Halifax was of little immediate

significance. At Quebec, however, it was at that moment being carried

into effect for much the same reasons it had appealed to him and other

officers in the Halifax command. The reasons behind the commencement of

the Martello towers across the Plains of Abraham in 1808 rested in the

whole lethargic history of its fortification since the British triumph

in Canada in 1759. The towers were finally precipitated by the same

Anglo-American crisis that had prompted the new proposals for the

defence of Halifax.

The city of Quebec was the key to the control of the continental

interior for both France and England, and both nations understood the

basic principles of its defence. Quebec is located on a triangular point

of land at the junction of the St. Lawrence and Saint-Charles rivers.

The French exploited these natural river flanks and extended a line of

works between them facing toward the plain in the rear of the town. The

St. Lawrence scarp rose so steeply as to be unassailable within the line

of works, but on the other side the land dropped off more gently toward

the shallow Saint-Charles River which was fordable at low tide. Before

1759 this vulnerable flank was not defended by even a continuous wall

around the town.

Despite the importance of Quebec and the danger of a renewed French

war, the English were slow to improve its defences after 1763. Some work

was carried out on the Cape Diamond promontory between 1779 and 1783 but

because of the peace it was left unfinished. For many years nothing more

was done, though as early as 1791 Gother Mann reported to Lord

Dorchester the proper principles for its defence.

Mann proposed enclosing the entire two-mile circumference of the

upper town to prevent a coup de main and reduce an enemy to one

point of serious attack, across the Plains of Abraham. To defend this

vital flank he wanted to carry a line of outworks to the Heights of

Abraham, forcing an enemy to reduce them before he could open batteries

against the main defensive line. Mann further proposed a citadel on Cape

Diamond to serve as a keep for the whole. In Mann's opinion these three

defensive lines, in conjunction with the short Canadian campaign season,

would be sufficient to retain Quebec until it was relieved by the onset

of winter or the arrival of reinforcements. No immediate action was

taken and Mann left Quebec, only to be recalled from the army in

Flanders in 1794 for the express purpose of carrying into immediate

effect part of his design for its defence. Priorities changed again and

almost nothing had been accomplished as late as 1804, though Mann

reiterated his proposals in 1799 and 1804, each time stressing "the

manner and expediency of occupying the Heights of Abraham . . . for the

better defence of the City of Quebec."39

Mann listed the occupation of the heights as second in importance

after the completion of the line wall around the upper town. Once it was

finished any attack must necessarily be funnelled across the Plains of

Abraham, from which the whole main defensive line was commanded from the

Ursuline to the barrack bastions at 800 yards distance. From there an

attacking force could open a regular siege and bombardment of the main

works. The heights were a difficult defensive proposition because, as

Mann explained.

although too near the Town to be left to the possession of an

Enemy they are on the other hand too distant to allow of the works which

might be constructed there, to be connected with those of the place.

They must, therefore, be regarded as detached

works.40

Mann therefore recommended four strong mutually flanking redoubts

across the heights, scarped in masonry and provided with defensible

masonry blockhouses as keeps. The redoubts were to be connected by

fieldworks and supported in an emergency by an entrenched camp in their

rear. He felt it unnecessary that these works have a great profile, and,

as well, it would have been difficult to excavate deep ditches in the

rock. He estimated the redoubts would cost £12,000 in all.

Mann had been closely concerned with the defence of Quebec from 1789

when he was a relatively junior officer, but by 1804 he was a

major-general in the army and an influential colonel of engineers. His

last proposal was taken up by the Committee of Engineers in England and

sparked a controversy with its chairman, General Morse, the Inspector

General of Fortifications. Morse refused to recommend the works of the

plains because from the heights the town works could not be reduced, and

"in the event of these advanced works being forced the troops would be

liable to great loss in their retreat." Mann responded that if the

heights were not defended they could be used to provide covering fire to

move batteries within 450 yards of the main works, from which distance

they could be breached.41 Mann's view was strongly sustained

by the Earl of Chatham, the Master General of the Ordnance, who took up

his case with the Earl of Camden, the Secretary for War, saying,

as I have no idea of any circumstances, under which the attack of

Quebec could be likely to take place, that would not render this measure

of peculiar advantage and utility, even independent of the assistance of

these outworks to the Defence of the place.42

At the same time Chatham saw no urgency in constructing the outworks

as the Plains of Abraham could be occupied quickly by guns and

fieldworks in an emergency.

Fifteen years of endeavour on Gother Mann's part failed to achieve a

commitment to permanent works for the Plains of Abraham. As long as the

drawn-out French war remained an essentially European conflict, the

proper defence of Quebec was a matter of no great urgency or consequence

as any attack on it was contingent on the triumph of French sea power.

By 1807, however, deteriorating Anglo-American relations and the

imminent prospect of another American war placed a hostile power at the

doorstep of Quebec. The British government feared that in the event of

war American naval inferiority might produce a compensatory invasion of

British North America. Any attack along the extended and indefensible

frontier would necessarily be directed at Halifax or Quebec; a sudden

successful attack on Quebec could deprive Great Britain of the whole

continental interior and the means of re-entering it before succour

could be sent from England. Consequently the new governor general of

British North America, Lieutenant-General Sir James Craig, was

instructed in August 1807, just prior to his departure from Britain,

to improve the defences of Quebec and defend it to the

utmost.43

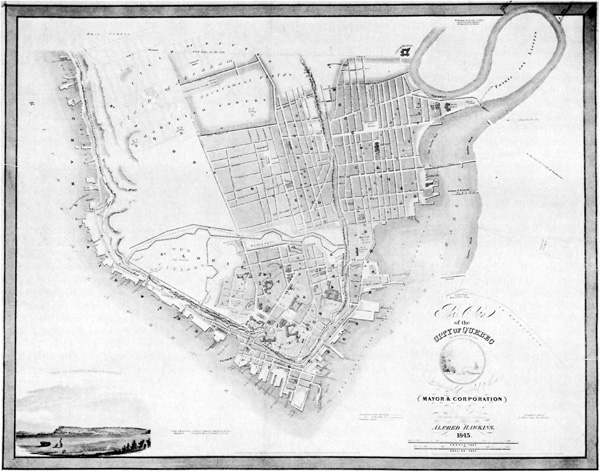

2 Plan of the city of Quebec, 1845, showing the locations of the four

Martello towers.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Craig arrived at Quebec late in 1807, with instructions to build

temporary works to prolong the siege in case of war or to improve the

permanent works if there were no war. The Embargo Act passed by the

American Congress on 22 December 1807 eased but did not eliminate the

possibility of war.44 In the spring of 1808 Craig found an

essential conflict in his instructions, as the measures demanded by each

contigency were quite different, and he confessed himself unable to

assess the likelihood of war; at the same time he felt it would be

foolish to wait on a result. Craig was opposed to unnecessary and

wasteful expenditures on temporary works, and so compromised by

commencing those permanent works that would be of the most immediate use

in supplementing the dangerously exposed existing fortifications.

In general, Craig accepted Gother Mann's assessment of Quebec's

tactical needs. The order of priorities was: completing the wall around

the town, covering and protecting the exposed town walls, strengthening

the outworks in front of Cape Diamond and occupying the Heights of

Abraham with advanced towers. Craig stressed that if all were not done

the remainder would be useless and Quebec not defensible for four days.

He acknowledged the necessity of a citadel on Cape Diamond to complete

the defences, but deemed it beyond his time and

resources.45

Craig's first three measures were not at all controversial; they were

in accord with the accepted needs of Quebec and within the scope of his

instructions. These same instructions, however, had specifically

precluded his proceeding to a permanent occupation of the heights before

referring his views to the home government for decision. In the event

Craig, impressed by the vulnerability of the works from the plains, did

not report any of his measures home until July 1808, when all were in

progress.46

Using the general ambiguity of his instructions as an excuse, he

stated that the absolute necessity of occupying the heights was too

obvious for much deliberation.

But the mode most eligible under the circumstances of our

situation of doing so, required every consideration that we could give

to it. . . the occupying them at the least expense of men has been the

principal object with us — and it is upon that principle as well as

on the consideration of their requiring the least time in their

construction, that we have determined on a range of Towers on the most

commanding spots across the height, four of them will be sufficient but

in order to furnish a more considerable line of fire than they would

afford, we proposed a small work connected with that which has the most

extensive command, — we are well aware of the objections that may

be made against the mode, but we are not the less convinced that under

all the circumstances of the situation, it has very far the advantage

over every other that could be proposed and we shall endeavour in their

construction to adapt the best means for meeting the circumstances on

which those objections are founded. I have no doubt my Lord that

Engineers whom your Lordship may consult will advance and enforce those

objections, nor will the limits of a letter admit of my entering into

that discussion upon the subject, that might be necessary to encounter

their arguments; but I agree most perfectly with Lieut.-Colonel Bruyeres

who commands the Department here, and a reference home on a subject, on

which there would be such a diversity of opinions, would certainly have

consumed that time in which they ought to be

constructed.47

Thus the British government was informed that four Martello towers

were already in process of erection at Quebec. A reference to Mann's

experience would indicate that Craig was correct in his private view

that a referral of the issue would "probably have been the occasion of

its never being done."46 His action was accepted without

demur and construction was permitted to proceed.

While Craig's contravention of his instructions ensured the building

of the towers, his disinclination to discuss the issue leaves the origin

of their choice in some obscurity. It seems likely that the decision to

use Martello towers originated with Craig himself, rather than with

Bruyeres, the Commanding Royal Engineer. This is particularly indicated

by the fact that Craig was responsible for the commencement of two

towers at the Cape of Good Hope in 1796 and was the commander of one of

the affected English military districts when the English tower idea was

conceived in 1803 and 1804. This assessment is corroborated in a letter

from Bruyeres to his counterpart in Halifax in March 1808, asking for

plans of the largest tower constructed there and for a description of

the point on which it was located. This information was returned on 18

March 1808. In the event, the Quebec towers, three of which were

completed by November 1810,49 owed a far greater structural

debt to their counterparts in Great Britain than to the Prince of Wales

Tower. The reference to Halifax was probably an attempt to justify the

use of the towers in a land defence role.

The proposed towers were not named but simply numbered consecutively

from the left, or St. Lawrence, flank. They were to be of one design but

of two different sizes. Towers 1 and 4, at the extremities of the line

overlooking the St. Lawrence and Saint-Charles rivers respectively, were

intended to be one-gun towers 45 ft. in diameter and 30 ft. high; towers

2 and 3, spaced evenly along the centre of the line, were to be

three-gun towers of the same height but 52 ft. in exterior diameter. The

cost of the four was estimated at £8,000 in all, while a proposed

redoubt in advance of tower 2 would have added another £5,000 to

the cost of the line. This redoubt, with a masonry scarp, two bombproof

caponiers to defend its ditch and bombproof casemates for troops and

stores, was intended to bolster the tower line at its highest point. The

line of towers was about 850 yards in front of the main works of Quebec

and in advance of the suburbs of the town. They were placed at roughly

equal distances in a 1,200-yard extension across the

plains.50

While the four Martello towers were one of the salient points of

Craig's and Bruyeres' plan of 1808, they by no means exhausted the

anticipated utility of such structures at Quebec. The same plan called

for a one-gun tower in advance of the old Cape Diamond outworks to

command the beach and cliff of the Anse des Mines, at a cost of

£1,800. A strong one-gun tower similar to those on the plains was

to be built on the opposite side of the Saint-Charles to command the

point of enfilade of the town works some 900 yards distant at

£3,000, and a similar one-gun tower on Point Lévis on the opposite

shore of the St. Lawrence, 1,500 yards away, to prevent a bombardment

from that quarter. However, the short working season for masonry and the

labour shortage induced by wartime prosperity combined to slow the works

in 1808, so none of these three towers was ever built.51

The same factors mitigated against an early completion of the towers

on the heights, though Craig accorded them a high priority. At the end

of 1810 he had to report that, "with all the assiduity we could extend

on them, however, we have only been able to finish three of the four

proposed towers and lay the foundation of the remaining one." Work on

tower 4 overlooking the Saint-Charles River continued in 1811 when the

construction was carried to an advanced stage, though it was not

completed in that year. The tower's advanced state and the threat and

then outbreak of hostilities in 1812 ensured its completion early in

that year,52 and all four towers were serviceable by the

onset of war.

The Quebec towers were built under the authority of the commander of

the forces in Lower Canada, and as such were funded from the military

chest and not carried to Parliament as part of the Ordnance estimate.

The towers were constructed as far as possible with military labour and

under the direct supervision of the engineer department. This method of

constructing the towers resulted in a confused tenure of the ground on

which they stood, as the sites were simply appropriated by the military

in the 1808 emergency. All of this land was owned by the Ursuline and

Hotel Dieu convents which, until 1787, had kept it entirely open. In

that year, against Gother Mann's advice, they were allowed to enclose

and lease it. By 1808 most of the property was in the possession of

long-term leaseholders who claimed losses as a result of the action of

the military. These claims were not sustained, but the tenure of the

land around the towers was only regularized piecemeal by purchase,

between 1811 and 1822, at a cost of £6,624. Such purchases were

necessary to ensure that the towers would not be closely enclosed by

substantial fences and buildings that would restrict their fields of

fire and hamper their military use. In 1808 part of the town works had

already been blocked by houses53 and later the towers in

their turn were to be masked as land prices inflated beyond the military

capacity of purchase. At Quebec and throughout British North America

generally to a lesser degree, the military fought a losing battle

against relentless civilian encroachments on the accepted 600-yard clear

fire arc in front of works.

In 1812, however, all of the towers on the Plains of Abraham were

completed well in advance of the town and armed to resist the invader,

though that capacity was never used and their military value never

tested. The proposed redoubt around tower 2 was not completed due to the

remoteness of the war, though materials were gathered for it and the

ditch excavated in 1811. At least towers 1 and 2, and presumably all

four towers, were surrounded by picket fences in addition to the ditch

around tower 2. These fences would have been intended for domestic

security rather than active military use. All of the towers were,

apparently, later provided with ditches to reduce the dangers of

escalade.54

The four towers were not built exactly according to the dimensions

laid down by Bruyeres in 1808. Their external dimensions as completed

were: tower 1, 44 ft. 6 in. diameter and 29 ft. 1 in. high to the

parapet; tower 2, 56 ft. diameter, and 33 ft. to the parapet; tower 3,

56 ft. diameter, and 33 ft. to the parapet; tower 4, 42 ft. 6 in. in

diameter, and 26 ft. 6 in. to the parapet. All sloped inward somewhat

toward the top. Thus towers 2 and 3 were identical while towers 1 and 4

showed minor variations. This pattern was carried over into other

aspects of the tower construction; the structural variations between the

supposedly identical towers 1 and 4 being greater than between the other

supposedly identical pair. All the variations were in detail, however,

as all four towers were of an essentially similar pattern. All were of

sandstone ashlar masonry exterior construction with a circular exterior

form and circular interior compartments within their thick rubble walls.

These compartments, comprising the basement and barrack floors of the

towers, were not concentric within the exterior faces of the works, but

were in the English fashion offset toward the eastern face. This added

to the thickness of the walls on the western side toward the plains, the

only possible avenue of attack. The approximate wall proportions were 6

ft. minimum and 11 ft. maximum.55

Again, in emulation of the English Martello towers, the only entrance

to those at Quebec was by a single door opening into the barrack level

of each tower. All of the doors were on the side nearest the town works.

The lower floor of each tower appears to have been ventilated by baffled

air holes.56

The interior compartment of each tower was surmounted by a bombproof

annular arch. In the Quebec towers the pillars were solid masonry and

extended uniformly from the foundation to the spring of the arch. Each

of the brick arches was topped by several feet of masonry to the base of

the platform on top, giving a total thickness of 5 ft. of bombproofing

in towers 1 and 4 and 6 ft. in towers 2 and 3. Each of the towers was

also equipped with a small bombproof magazine in the basement, with an

approximate capacity of 75 barrels for the smaller towers and 150

barrels for the larger. The remainder of the basement floors was

unpartitioned and reserved for storage purposes. The earliest available

tower plans do not indicate the presence of water storage tanks beneath

the wooden basement floors of the towers. They are, however, clearly

indicated in later descriptions57 and this may well indicate

a deficiency in the early plans.

The floor between the basement and barrack levels was of wood, and

access to the basement was provided by a trapdoor and stairs through the

floor. The basement floor itself appears to have been only about 7 ft.

high, while the barrack level above was 8 ft. to the spring of the arch.

Each of the barrack floors contained a fireplace venting through a

chimney to the parapet,58 and each was at one time fitted up

with a tier of double wooden berths (though these were later removed)

between the embrasures of the interior of their western walls. In this

manner the larger towers could provide regular accommodation for 20 men,

though all were intended to house larger numbers in an emergency.

Each of the four towers was pierced by two embrasures for guns or

carronades at the barrack level. In both the two larger towers (2 and 3)

these faced north and south directly along the axis of the tower line,

while in towers 1 and 4 the embrasures were angled slightly back toward

the main works. Thus none of the embrasures in the interior of the

towers was designed to fire directly out upon an enemy force advancing

from the west, but each was limited to a lateral or reverse

fire.59 The offensive fire role was reserved to the ordnance

mounted en barbette on the top platform of the towers.

In each case access to the platform was by a stairway from the

barrack level set into the thickest part of the exterior wall. The

parapet of each tower was higher as well as thicker on its westward

face, thus providing extra protection for the gunners on that side and

rendering the platforms untenable if taken by an enemy intending to turn

the ordnance against the main works. The terrepleins of the towers were

not regular circles as they were in Edward's Halifax towers. At Quebec,

in the English manner, the top of each tower was filled in so as just to

accommodate the intended arc of the traversing platforms of the

ordnance.

Towers 2 and 3 were intended for three guns and were shaped

accordingly. During the War of 1812, however, tower 2 was adapted for

two extra pieces of ordnance so it mounted five guns on its terreplein

in addition to the two 9-pounder guns in embrasures on the barrack

floor. These included one 68-pounder carronade in embrasure, two

9-pounder guns en barbette on traversing platforms and two 24-pounder

guns similarily mounted. Tower 3 was armed in like fashion, except that

it had no 9-pounders on top, though preparations were made for them. The

two smaller towers (1 and 4) were much more lightly armed as they

contained no interior ordnance and only one gun each on top. At tower 1,

armed at the same time as towers 2 and 3, this ordnance was a 24-pounder

gun. By December 1812 the newly completed tower 4 facing the

Saint-Charles was armed with a single 18-pounder gun. On towers 1 and 4

the guns were mounted on traversing platforms en barbette and traversed

a full circle from a central pivot.60 This ordnance remained

unaltered until long after the conclusion of the War of 1812.

The only strikingly unusual terreplein feature of the Quebec Martello

towers was at tower 4 where a surface gallery was formed within the

parapet itself, extending nearly half the way around the tower in its

east and north faces. This gallery, set back 2 ft. 6 in. from the

exterior of the parapet, was 3 ft. 9 in. wide with a banquette step, and

offered about 5 ft. of cover on its exterior side. It was apparently

designed to accommodate infantry firing in the direction of the

Saint-Charles River without hampering the working of the gun at the

centre of the terreplein.61

The Quebec Martello towers, conceived and carried to completion on

the personal initiative of the military governor of Lower Canada, were

to be the most English of all those constructed in Canada. There were,

however, minor structural discrepancies undertaken to adapt the towers

to local circumstances which the English design was never intended to

meet. Their positioning was analogous to that of the English towers in

that they had only a single obvious avenue of approach: this approach,

however, left them exposed to a severe battering fire from stable

land-based guns. Although the towers were completed, armed and equipped

for service by the beginning of the War of 1812, and apparently

garrisoned against a surprise attack, Craig's wisdom in ordering their

construction was never put to the test of battle.

Georges Island Tower

Although neither the main permanent sea or land defences of the

eastern inhabited portion of British North America was tested between

1812 and 1815, Edward's Halifax and Craig's Quebec towers were joined by

another Martello tower before hostilities were more than barely under

way. This last work was the Georges Island tower located on the island

of the same name in Halifax harbour. While Nicolls's 1808 proposal for

Halifax and Craig's Quebec towers of the same year had been prompted by

fears of an American overland assault, the new Halifax tower was

inspired by the worry in both England and Nova Scotia that Halifax's

aging and inefficient sea defences might fall to a small American naval

force in the absence of the British fleet. In that eventuality, Britain

would lose at once her principal naval base in the western North

Atlantic and one of her two main springboards for offensive operations

against the Atlantic coast of the United States.

While the Halifax sea defence batteries were never adequate in the

era of smoothbore ordnance because of the great breadth of the harbour,

Georges Island was the principal bulwark of those defences and was

reorganized as such.

The island had first been fortified in 1750, only a year after the

founding of the town. At the end of the American Revolution its

batteries mounted 48 pieces of ordnance behind decaying earthworks.

Shortly after his arrival in 1794, Prince Edward, the Duke of Kent,

described it as "of all situations the best for the defence of the

Harbour, as it makes a formidable cross-fire, with the Batteries, both

on the adjacent and opposite shores." At that time he deemed it

indefensible in its existing state and resolved on erecting there a

"star fort" for 300 men with a blockhouse keep in the interior. This

work was accorded a high priority and completed before his departure in

1800.

The fortifications were defective in every essential; there was a lot

of dead ground on the island and the square wooden blockhouse provided

insufficient accommodation for the intended garrison. It was these

defects that gave rise to Captain Fenwick's first unsuccessful proposal

to build a tower there in 1800.

In 1805 Fenwick renewed his suggestion for a strong tower to prevent

the earthworks being carried by assault and the whole harbour defence

jeopardized. It too was rejected. Nonetheless, the American war scare of

1807-08 emphasized the necessity for some alterations. Partial

reconstruction was rejected as ineffectual, and on 4 March 1810 the

Committee of Engineers in England, of which Colonel William Twiss was a

member, authorized the total reformation of the earthwork and the

erection of a stone tower in its centre to replace the blockhouse and

substitute for the defective subterranean magazine. The armament of the

new tower was intended to sweep both of the new island batteries and

command the shoreline beyond. Although this plan was approved in April

1811, a labour shortage in Halifax delayed construction until the spring

of 1812 when, with war in the offing. it was rushed forward. The walls

were six feet high in July and it was completed and very probably armed

before the end of the year.62

When completed, the circular tower was approximately 43 ft. in

exterior diameter at the base, with a masonry exterior wall 7 ft. thick

at bottom. By then it appears to have been a standardized two-storey

stone tower surmounted by a terreplein and parapet. It had four cannon

embrasures on the barrack floor besides being loopholed for musketry on

both floors. Its bombproof arch and the masonry platform over the

barrack floor were supported by a solid central brick or masonry pillar

5 ft. in diameter. The means used to enter the tower are not known,

though it appears the main access was by a ground floor door on the

Citadel side where the tower was presumed to be liable to covering fire

from that shore if it was assaulted. Communication from ground to

barrack levels was by a staircase in the wall. A brick magazine 15.3 ft.

x 10.3 ft. x 5.3 ft. was built on the lower floor of the tower and

pressed into immediate service to store the island's reserve ammunition.

The remainder of the lower level was fitted up with a wooden banquette

all round to serve the loopholes. The barrack floor above had two

fireplaces for cooking and heating, and a wooden officers' room was

later partitioned off on that level.63

In the war period each of the barrack floor embrasures was equipped

with a 12-pounder carronade mounted on an oak slide. There were four

24-pounder carronades en barbette on traversing platforms. This armament

appears to have been light for so important a work, but, in fact, would

have been quite adequate for a tower sandwiched between two heavy sea

batteries. Its principal task was to sweep the perimeter of an island

only 800 feet by 500 feet.64 The above ordnance could have

performed this chore at pointblank range.

Though the tower may have been garrisoned against a surprise attack

during the War of 1812, its armament found no employment. Neither did it

make any structural contribution to the evolution of Martello towers,

being, from all reports, a most orthodox structure. Its presence on

Georges Island, however, was a classic application of the Martello

tower. It combined Twiss's recommended use of them as battery keeps with

the English requisite that they be exposed, if possible, only to gunfire

from naval vessels. The impossibility of opening land batteries against

it at a moderate range and the capacity of the island's batteries to

keep ships at a distance must have made it in 1812-15 the most secure

Martello tower in the British empire.

Carleton Martello Tower

The safety of the Georges Island tower was in marked contrast to that

of another Martello tower erected in British North America about the

same time. The Carleton tower was constructed on an isolated height of

land on the west side of the harbour of Saint John, New Brunswick,

between 1813 and 1815. It also was built largely on the British pattern,

and circumstances were to combine to make it among the least useful of

all those constructed in British North America.

The Carleton Martello tower had its origins in a survey of the New

Brunswick defences executed by Captain Gustavus Nicolls, who was still

Commanding Royal Engineer at Halifax in October and November 1812. At

that time Halifax and most of Nova Scotia were considered immune to

overland attack, barring major and unexpected reversals at sea. New

Brunswick, however, was not so fortunately situated as it shared an

extensive, sparsely populated and largely indefensible land frontier

with the United States. Nicolls despaired of holding the interior in the

face of an American overland expedition, and commended its defence to

the militia and to such fieldworks as they could erect.

The city of Saint John, as the province's main entrepôt, commercial

centre and chief repository of naval and military stores, fell into

quite another category. Nicolls felt its hastily prepared harbour

batteries were capable of defending it against such desultory raids as

the Americans were likely to mount against it by sea, as it was of small

overall strategic importance. Nevertheless the threat was still present,

for while geography nearly precluded assault by an American military

force landed by sea to the east, it was subject to a land attack from

the west either from troops landed on the nearby coast or coming

overland via the St. Andrews road. Thus any military expedition against

Saint John would bring an enemy to the same point, the town of Carleton

on the western shore of the harbour opposite Saint John. From this point

the city could be safely bombarded.

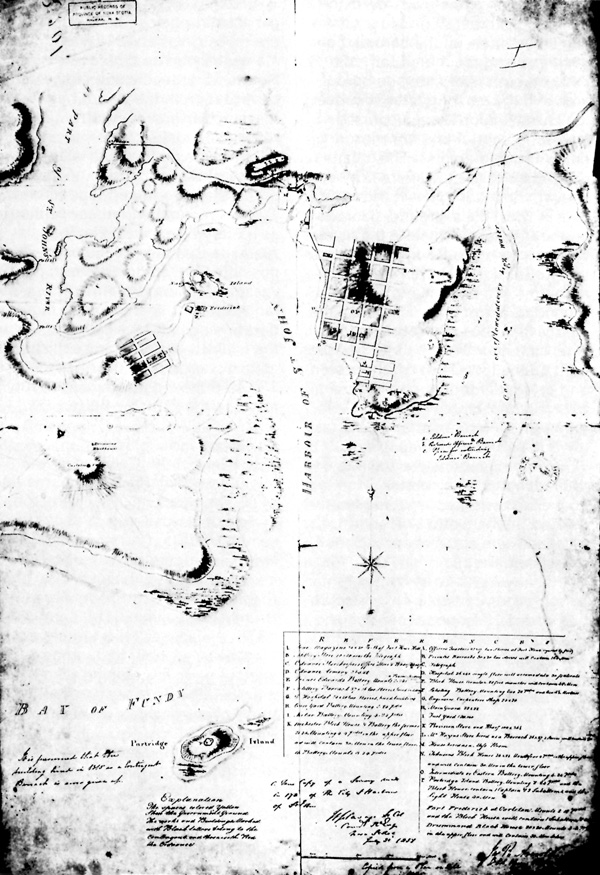

3 Plan of Saint John, N.B., 1814, showing carleton tower and other

defence works.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Consequently the heights in the rear of the town constituted a

position of some considerable military significance. The position was

also potentially strong, flanked on the right by the Saint John River

and on the left by the Bay of Fundy. In November 1812 Nicolls proposed

defending it with a chain of four redoubts, adding, "I . . . think the