|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 20

The History of Fort Langley, 1827-96

by Mary K. Cullen

The Twilight Years

At the beginning of the 1860s Hudson's Bay Company trade in British

Columbia was in a state of transition. The interruption caused by the

loss of its exclusive trading licence was aggravated by depression in

business generally and uncertainty with respect to Company land claims

in the new colony. As reports of gold strikes far up the Fraser spread

in 1861, the great Cariboo rush which peaked in 1862 and 1863 introduced

new confidence into the British Columbia economy and a plan on the part

of the Company to harness its posts in support of a supply system to the

mines. This decision and the final settlement of land titles in 1864

were the signal for redevelopment of Langley Farm and reactivation of

other commercial enterprises such as salmon packing. Ultimately,

however, rising costs of labour and competition from more strategic and

larger centres proved too strong and even relocation of the saleshop in

the adjacent village did not result in a viable business. For the

Hudson's Bay Company at Langley, the birth of British Columbia had

ushered in the twilight years.

Following the departure of Yale in May 1859, Fort Langley lapsed into

a period of inactivity and mismanagement. W.H. Newton, accountant at the

fort, supervised operations until January 1860. He was replaced by Chief

Trader George Blenkinsop for seven months and in August 1860 reassumed

charge with a reduced staff of seven.1 The functions of the

post were minimal. Blacksmith James Taylor and his assistant R. Bayley

continued to make beaver traps, axes and other iron works for the

interior brigades. Two men stationed at the Indian fishing station on

the Chilliwack salted salmon for home consumption while Cromarty, cooper

at Langley since 1846, turned out barrels for Company use and local

sale. There was one labourer, Narcisse Falerdeau, and one store clerk,

Kenneth Morrison. Operations were simplified by abolishing the Indian

shop and admitting native people to trade in the saleshop.2

An inspection of the place in December 1861 indicated things were only

in a "very so so order." Chief Factors Tolmie and McTavish found that

Newton had "no knowledge about business or the management of a place

like Langley" and that the stores and warehouses were in "a fearful

state with dirt and confusion for which there is no

excuse."3

When rumour abounded in 1858 and 1859 that old Langley might be made

capital or the chief commercial town of British Columbia or both, the

board of management considered relocating the fort. The Company store

seemed poorly situated for business and owing to a gradual silting up of

the river channel directly in front of Fort Langley, its wharf had

become less accessible to steamers. Chief Factor Dallas proposed

removing the saleshop and office dwelling to the site lower down the

stream long used by the Company as a point of embarkation for salt

salmon. Unfortunately, the land there was disposed of at the government

sale of town lots.4 Clearly a move to any new site would have

to be deterred until Company land claims at Langley and other posts in

British Columbia were precisely defined.

Langley Farm, rented to C.R. Bedford in March 1859, was repossessed

by the Hudson's Bay Company in July 1860 after Bedford failed to produce

the annual accounts required by the rental agreement.5 Most

of the existing stock of horses and milk cows were sold off, but the

number of beef cattle was augmented in order to supply the brigades

while at Fort Hope.6 Hay was also sent on to Fort Hope for

foddering the pack horses of the brigade train.7 In the

summer of 1860 Langley Farm made its first attempt at sheep raising,

grazing 400 ewes and wethers for eventual sale, live weight, in various

towns on the lower Fraser.8

When the rush to the Cariboo mines gathered force in 1861, the

Company established an inland transportation service, using Langley as

one station for breeding and grazing pack animals. Twenty-two mules

purchased from the Hawaiian Islands and sent to Langley in March 1861

were employed during the summer packing provisions between Fort Hope and

the junction of the Tulameen and Similkameen rivers (now Princeton);

from there the pieces were taken to Kamloops by horses.9

During the winter of 1861-62 Langley kept more mules for use on the Fort

Yale-Lytton trail and also horses for packing from Lytton to

Kamloops.10 With the inauguration of the Cariboo wagon road

from Yale to Clinton in the summer of 1863, the Company began to employ

wagons for transport some distance from Fort Yale. Langley made oxen

yokes for this service and also supplied hay at various road

houses.11

While Langley Farm supported the Company's brigade and mining

transport, development of a full-scale agricultural enterprise was

delayed until the Hudson's Bay Company was securely placed in possession

of its fort and farm lands by the colonial government. The imperial

government had early recognized a moral indebtedness to the Company

which might be paid through a generous disposition to land

grants,12 but if was not until October 1861, at a London

meeting between Her Majesty's government and the Hudson's Bay Company,

that a preliminary settlement of land claims was worked out. According

to this agreement the Company was entitled to the following land at

Langley:

New Fort Langley

The actual site of the Fort (stated by Mr. Dallas to be about 2

acres) with all surrounding Buildings and Enclosures or actually

cultivated or ploughed Lands, but not exceeding in the whole 200 acres,

and at Langley Farm (about 1 mile distant from the Fort Site) a quantity

of Land not exceeding 500 acres .... the Company ... to have the option

of purchasing at 4/2 per acre at Langley Farm (in addition to the 500

acres) any quantity of the surrounding Land which may have been

enclosed, cultivated, or ploughed, or sown with grass, not exceeding

1500 acres. This option to cease if not exercised within six Calendar

months of notice from the Governor to the Company's agent to select

lands.

Old Langley or Derby

Site of salmon store and wharf; and land adjoining not to exceed 2

acres in all.13

The colonial government surveyed the Langley lands in the fall of

1862 and forwarded tracings to the Company in February

1863.14 Having experienced legal difficulties with squatters

at Langley, the Company requested that its boundaries there be more

conspicuously marked than was the usual practice.15 This was

carried out in the spring of 186416 and on 12 April 1864 the

Company received a crown grant of three lots in group 2 of the official

survey for the district of New Westminster. These included lot 19, the

new fort site of 200 acres, lot 20, the old fort site of 2 acres and lot

21, 500 acres of Langley Farm south of the fort. On the same day the

Company received formal conveyance of lot 22, the remaining 1,500 acres

of Langley Farm which it had purchased at 4s. 2d. per

acre.17

The general management of both fort and Farm was taken over by Ovid

Allard in October 1854. Allard had served as Indian trader and

interpreter at Fort Langley from 1839 to 1852 and had been lately

officer in charge at Fort Yale.18 His tenure at Langley was

marked by efficiency and resourcefulness. He put new life into sales and

increased trade in furs, but his most notable contribution was a revival

of salmon curing. On Allard's initiative enough salmon was cured at

Langley in 1865 to allow a small shipment to the Hawaiian Islands. The

net proceeds of $15 a barrel convinced the board of management to

continue exportation.19 Cromarty made the barrels and Allard,

competing successfully with other buyers, purchased salmon at ten cents

each and delivered the packed fish to Victoria at a cost price of eight

dollars per barrel.20 About 100 barrels were produced for

foreign trade annually until the end of the decade when the

establishment of commerce and the focus of the fishery at the mouth of

the Fraser made the Langley venture unprofitable.21

By 1865 the buildings at the fort were fast decaying and much of the

old lumber was used to build sheds on the farm.22 Relocation

of the fort, first mooted in 1858-59, was now intimately tied to the

larger consideration of steam shipping on the Fraser. Extension of steam

service to Forts Hope and Yale during the gold rush had quickly

indicated the significance of transportation in determining the centres

of commercial prominence. Thus, even after New Westminster had been

selected as capital and port of entry, the board of management did not

abandon the idea of Langley as an important commercial town. By

obtaining control of steam shipping from Victoria to Fort Yale, it

proposed to make Langley the connecting point between sea and river

steamers.23 Since 1859 the Hudson's Bay Company steamer

Enterprise, from Victoria, connected at New Westminster with the

two sternwheelers, Reliance and Onward, owned by Captain

Irving. When Irving offered these boats for sale in 1865 the board

strongly urged their purchase, not only to prevent the entire traffic

from falling into American hands, but also to "have a more controlling

commercial position at Hope, Yale and New Westminster" and to "bring

Langley into a more important position by arranging that the boats

should stop there long enough to allow passenger's to purchase at the

Company's store."24 In the fall Tolmie selected a new site at

Langley for a store, dwelling and other necessary

buildings.25 The opportunity to buy Irving's boats, however,

was later matched against a government subsidy for steam service from

San Francisco to Victoria and a contract to build a steamer for the

navigation of Kamloops and Shuswap lakes. The board chose the immediate

benefit of transportation in the gold district and selling through

steamboat tickets from San Francisco to the Big Bend.26

Irving was persuaded to continue service on the lower Fraser and Company

plans for moving Fort Langley were postponed. Correspondence between

Victoria and London in October 1866 suggested that the relocation of

Langley post and its future development were still tied to Company

control of Fraser River transportation. In a letter to London secretary

Thomas Fraser, Tolmie recommended,

it would be adviseable soon to lay off a townsite on the Company's

property at Langley, and to sell lots, for which some enquiry has

already been made. It must be our endeavour to make Langley the point

of meeting, for the exchange of passengers and goods between the Gulf

and River steamers. But this can hardly be attempted until the Company

own boats on Fraser River.27

Six months later Company purchase of the Reliance and

Onward was again postponed, this time by the insertion of a

clause in the Shipping Act authorizing the governor to admit foreign

shipping to the coast and up-river trade.28 The board of

management was convinced that the clause was intended chiefly to deter

the Company, had it owned Irving's boats, from transferring the

forwarding business from New Westminster to Langley.29 Their

conclusion that every endeavour to develop Langley would be impeded by

new government measures to protect the interests of New

Westminster30 seemed to lead to acceptance of Langley's

decline.

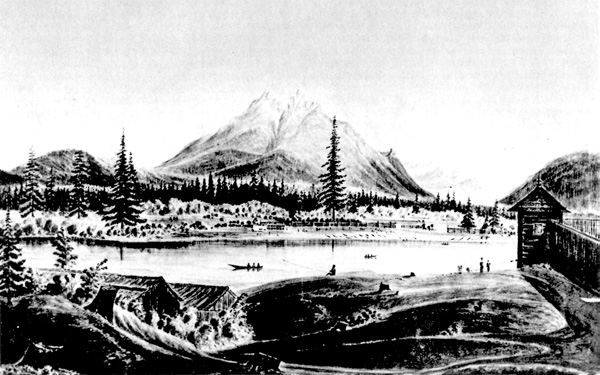

24 Watercolour of the Fraser River drawn from Fort Langley in 1860

by James M. Alden, an American officer serving as a field artist with

the British-American Boundary Commission.

(U.S. National Archives, Washington, D.C.)

|

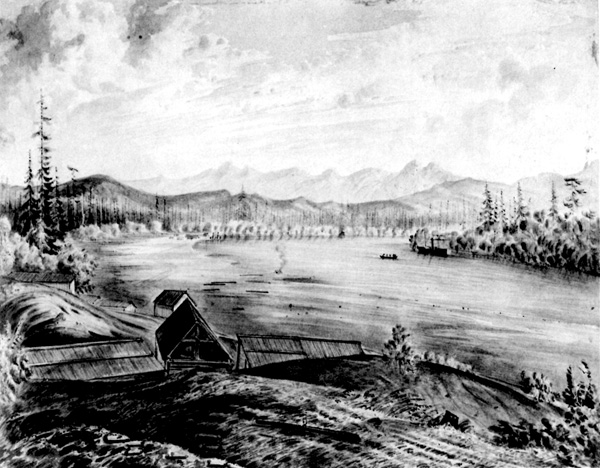

25 View from Fort Langley downriver, 1860, by James M. Alden.

(U.S. National Archives, Washington, D. C.)

|

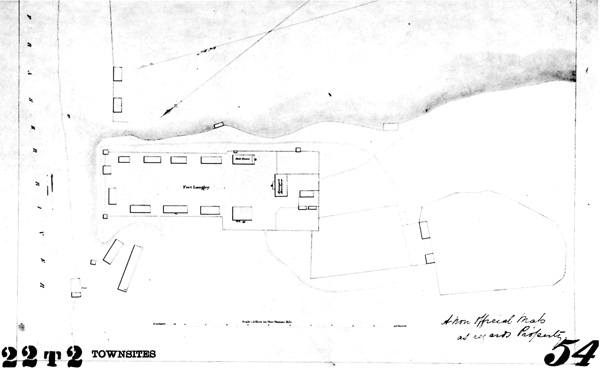

26 The only known plan of Fort Langley, drawn by Sergeant William

McColl, RE, 17 September 1862.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

27 Fort Langley, 1862.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

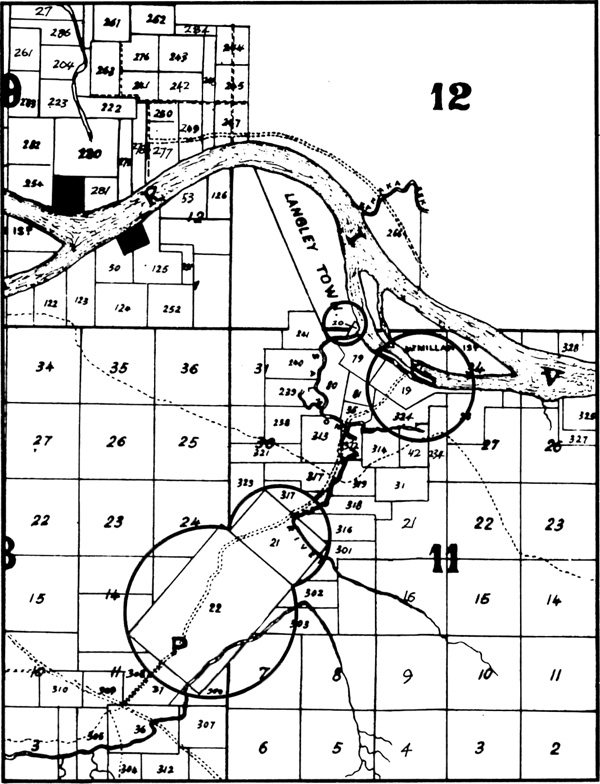

28 Part of "Map of New Westminster District B.C. 1876," British Columbia

Department of Lands and Works, drawn by F.G. Richards. Circled lots 19,

20, 21 and 22 show the Company's lands in oblique relationship to

surrounding lots.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

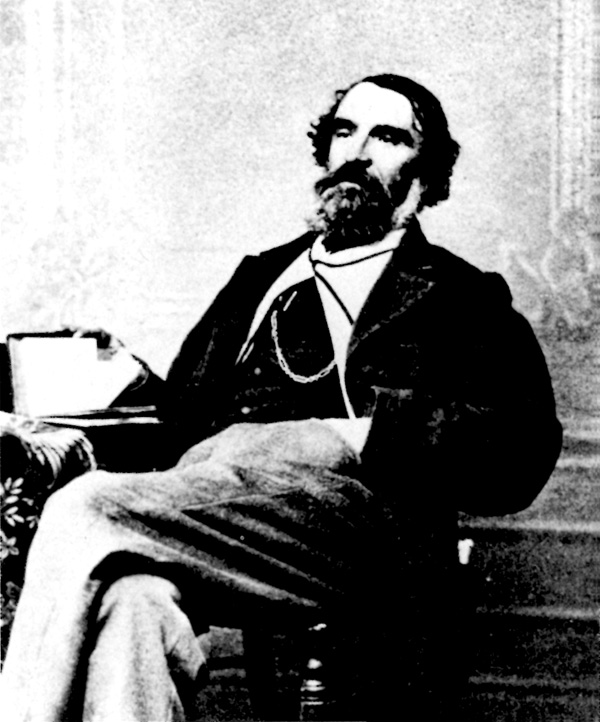

29 Ovid Allard, chief trader in charge of Fort Langley, 1864-74.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

Once plans for the commercial improvement of Langley post were

shelved, little capital was designated for the renewal of fort

buildings. A new roof and chimney were put on the blacksmith's shop in

March 1868,31 but the store was leaky,32 the

cooper's shop was no longer fit for barrelmaking33 and

several other buildings had fallen into disrepair. Allard reported in

September 1868 that he was pulling down one of these structures and

using the material to build a hay shed at the steamer

landing.34 In October 1871 the blacksmith's shop was made

into a dwelling house.35 The cooper's shop was fixed up as a

salesroom in January 187236 and by September the historic Big

House had been pulled down and a new house built for the manager of

Langley post.37 A drawing of the fort property dated April

1873 records three buildings — the Hudson's Bay Company house (just

one year old), the Company stores (the former cooper's shop) and

Cromarty's house (probably the converted blacksmith's

shop).38

The principal activity at Langley post in the late 1860s was farming.

By 1867 about 25 tons of oats and over 100 tons of hay were being

produced yearly.39 From this yield Langley supplied Fort Yale

with some of the grain and nearly all the hay used for feeding the

Company's wagon teams and pack trains when in for loads. It also fed a

huge stock of milk and beef cattle and marketed surplus hay and oats in

Victoria and New Westminster.40 In conjunction with the

Company's farm at Uplands, Vancouver Island, Langley Farm supplied the

steamers Enterprise and Onward and the Company stations of

Hope and Yale with butter, salted beef and pork and a variety of

vegetables such as potatoes, onions, cauliflower and peas.41

All the horses, mules and bullocks employed in the inland transport

business (in 1867, 20 yoke of oxen and 16 horses and mules) wintered at

Langley and hogs and beef raised there found a ready market among the

principal butchers of southern British Columbia.42

Despite the wide support which Langley Farm provided for the

Company's various operations in the Western Department, an assessment of

agriculture at Langley in September 1870 indicated the Company made

little or nothing by it. Because of the high rate of wages prevailing in

the colony of British Columbia, Langley's substantial returns from hay,

cattle, butter and sundry vegetables barely covered its outlay in

labourers' wages and provisions. In fact, produce could be purchased

more cheaply from California and Oregon than it could be raised locally

to supply the shipping and inland transport. Under these circumstances

there was "no object in any longer carrying on farming on account of the

Fur Trade." Approval was soon given to the board of management's

suggestion that farming operations at Langley should be discontinued and

the farm advertised for sale or lease.43

The conclusion of farming activities at Langley commenced in October

1870 when Allard received instructions from Victoria "to reduce the

number of hands employed on the farm to the lowest possible

number."44 The Langley stock were advertised for sale in the

Mainland Guardian in April 1871.45 Within three weeks 189

cattle had been sold for $5,636, more than $3,000 above their inventory

price.46 Farm produce was also worked off in large sales

throughout the year to Yale, Victoria and Burrard Inlet. By October 1871

agriculture at Langley had been reduced to a 26-acre47

gardening operation at the fort and the annual report on trade stated,

"the farm at this place is now closed."48

The Company tried, without success, to lease Langley Farm for five

years at about ten per cent per annum on the amount of the

improvements.49 Several parties without means applied for the

lease, but they were viewed as unsuitable because they wanted a long

lease and low rent, and were unable to give reasonable security that

they would not exhaust the land while they occupied it.50

Until it could obtain better terms, the Company decided to harvest the

hay annually and to employ William Harvey at the farm to keep the

buildings and fences in repair.51

The business of Fort Langley, while partially relieved from the

expense of the farm, showed diminishing profits in the early 1870s. The

fur trade fell off after 1872 owing to the increase and competition of

new buyers52 and the saleshop business was undermined by

merchants in New Westminster, who unlike the Hudson's Bay Company, took

farmers' produce in exchange for staples.53 Some salmon

continued to be cured and packed in barrels for the use of Company posts

and ships, but by 1874 the export market for barrel fish was almost

entirely replaced by Fraser River canned salmon, a growing operating in

which several companies were involved.54 During outfit 1874

trade was set back by the death of Allard, who had guided Langley's

destinies for the past decade. W.H. Newton, briefly officer in charge

for 1859-60 and 1863-64, succeeded Allard, but died in January

1875.55 Shortly after Henry Wark, former manager of the farm,

took charge of the fort business, opposition to the Company at Langley

was set up by a retail dealer and publican supported by New Westminster

merchants.56

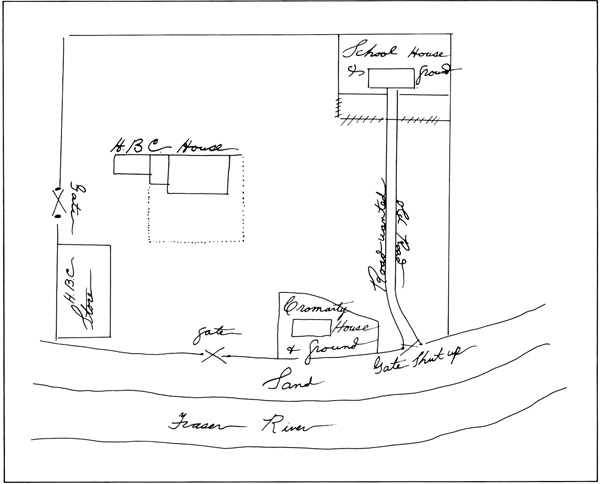

30 A ground plan of the remaining buildings at Fort Langley, drawn by

Mrs. W.H. Newton, April 1873.

(Hudson's Bay Company Archives.)

|

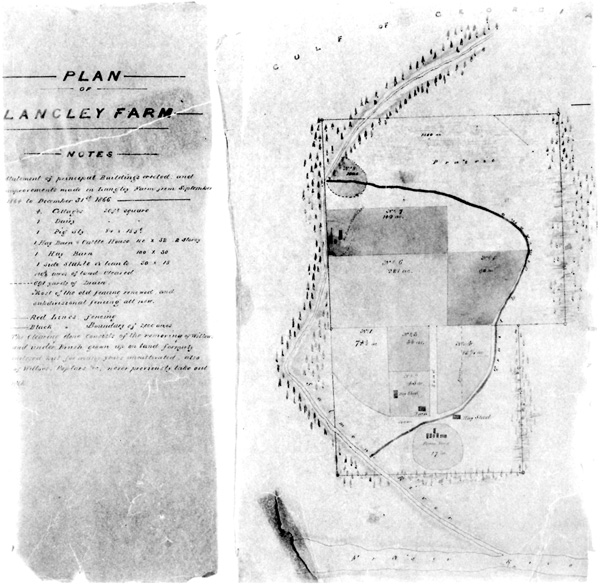

31 An 1866 plan of Langley Farm with a statement of the principal

buildings erected and improvements made there from September 1864

to 31 December 1866.

(Hudson's Bay Company Archives.)

|

The several difficulties facing trade at Langley and necessity for

improvement renewed Company determination to detach the farm from the

trade shop connection.57 It still seemed impractical to work

the farm to advantage. The land had not been laid down in grass since

1864, hay was getting inferior and there were no markets for it. Wark

reported, "the property is only a common for everybody's cattle and a

great eyesore."58 On 3 November 1876 the London board

approved a second effort to lease the farm, expressing "no desire

whatever to carry on trade at Fort Langley unless it can be done

profitably."59

In May 1877 Alexander Munro, the Company's land agent at Victoria,

reported difficulty in obtaining a tenant for Langley Farm on

satisfactory terms and recommended the sale of the property as bringing

a better income than could most likely be obtained as rent. According to

Munro, a farm of such dimensions required a large outlay to stock and

cultivate it while any farmer possessing the necessary capital and

willing to pay a fair rent would not accept the short term of years and

uncertain tenure offered by the Company. He had hoped to lease the farm

as a recruiting station for cattle bound for the Victoria market, but

found that upcountry stockraisers preferred to drive their stock

directly to market to realize on it immediately. Considering the growing

scarcity of land in the market near Langley and its probably enhanced

value should the railway follow the Fraser River, Munro strongly advised

selling Langley Farm. He added that the situation of the Company farm in

an oblique position relative to the government survey of the surrounding

district meant the eventual intersection of Company property by several

roads, a costly fencing operation to protect the land and potential

taxation by municipal authorities.60

During the summer of 1877 the idea of selling Langley Farm was fully

discussed in Winnipeg and London. Company officials, well aware of the

tax danger of holding large tracts of land near expanding

municipalities, were disposed to sell.61 At the same time

they were anxious to profit by the venture and to get the full benefit

to be derived from the proximity of the railway. They issued authority

to sell the farm in parts with the proviso that the sale be delayed one

season.62

Detailed preparations for the sale were made from Victoria in the

winter of 1877-78. One of the first tasks was to partition the

2,000-acre farm into equitable and saleable lots. Farm lots 21 and 22

were surveyed and divided into 20 subdivisions of approximately 100

acres each while the crooked road which traversed the farm from end to

end was run through the centre in a straight line to give each

subdivision road frontage.63 The general terms of sale were

fixed at one-fifth of the purchase money to be paid on signing the

agreement and the remainder in four equal annual instalments with seven

per cent interest on the unpaid balance.64 Early in December

the public was informed of the intended sale of Langley Farm and invited

to visit the property.65 Sale by auction was chosen as the

best means of stimulating competition and rewarding a fair decision to

the buyer.66 The auction, first announced in April, was to be

held on 17 June at the Hudson's Bay Company salesrooms, Wharf Street,

Victoria.67

The sales made at the 1878 auction of Langley Farm were

disappointingly small. Although each of the 20 lots was offered and

several of them without any upset price being stated, only four lots

found purchasers; number 1 at $25 per acre and numbers 6, 7 and 8 at $26

per acre. In his report of the sale, Munro attributed the unsatisfactory

result to two principal causes: (1) "that there are so few persons on

this coast able and willing to give more than a few dollars per acre for

farming land" and (2) that many people soon expected to buy cheap

reclaimed land in the Matsqui, Sumas and Chilliwack

districts.68 Even Ottawa's recent announcement of the

adoption of the Fraser valley as the railway route was greeted with

skepticism and did not materially benefit the sale.69 The

remaining 1,600 acres of Langley Farm were left to be sold by private

bargain over the next eight years.

The small retail operation at Fort Langley continued to fight a

defensive battle against new competitors in the 1880s. The saleshop,

managed with rigid economy and supplemented by sales of hay from the

farm, showed a reasonable remuneration of over $1,000 for outfits 1878

to 1880.70 As the various sections of Langley Farm were sold,

however, the proceeds from haying were substantially less. During

1881-82, the returns of the post slumped to $39.67.71 The

improvement of the business to a gain of $1,770.06 for outfit 1883 was

largely attributable to customers being steadily employed on railway and

other works in the immediate neighbourhood.72 Unfortunately,

this increased activity also brought into existence several other stores

in and near Langley which threatened to diminish the trade of the

Hudson's Bay Company.73 The physical arrangements of the

"fort" handicapped the Company in competition with these opponents.

Formerly the focus of activity on the Fraser, by 1885 the site of Fort

Langley lay on the periphery of commerce. Sandbanks had gradually filled

the river branch on the fort side of McMillan Island so that ships now

anchored about 400 yards short of Langley post.74 Since the

nearest centre of population, the town of Langley, was located west of

the steamboat landing, the Company post was "unlikely to command any

trade except in such articles as cannot be obtained

elsewhere."75 Its buildings there were old too. The manager's

residence had been built by Allard in 1872 while the store had

functioned as a cooper's shop long before its conversion to a salesroom

in 1871. After a visit to the site in December 1885, Assistant

Commissioner Thomas R. Smith reported that the store building was "very

old, and unfit to store any but heavy goods in."76 On Smith's

recommendation the Company decided to quit Fort Langley and to set up

new premises in the village near the wharf.

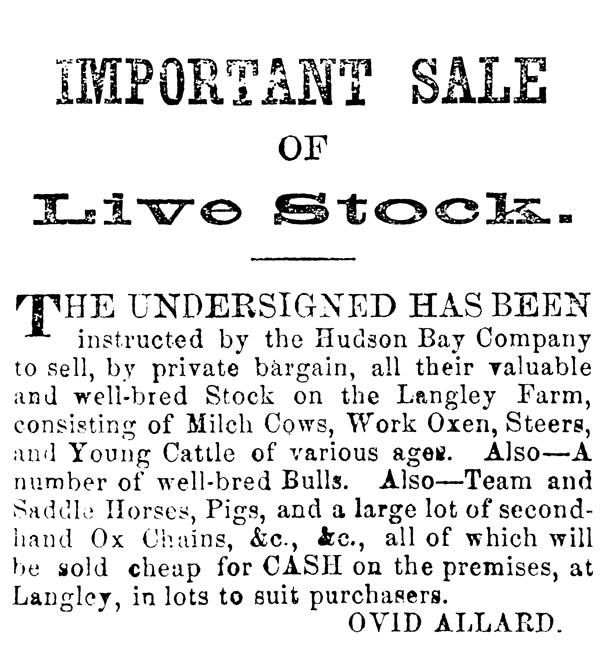

32 Advertisement for the sale of Langley livestock, Mainland Guardian,

New Westminster, B.C., 5 April 1871.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

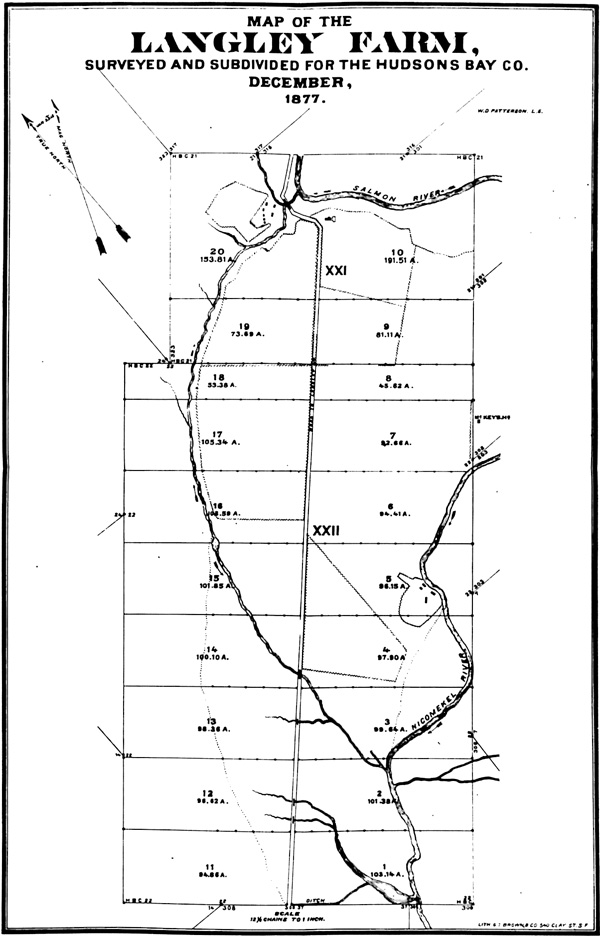

33 Langley Farm as subdivided for purposes of sale.

(Hudson's Bay Company Archives.)

|

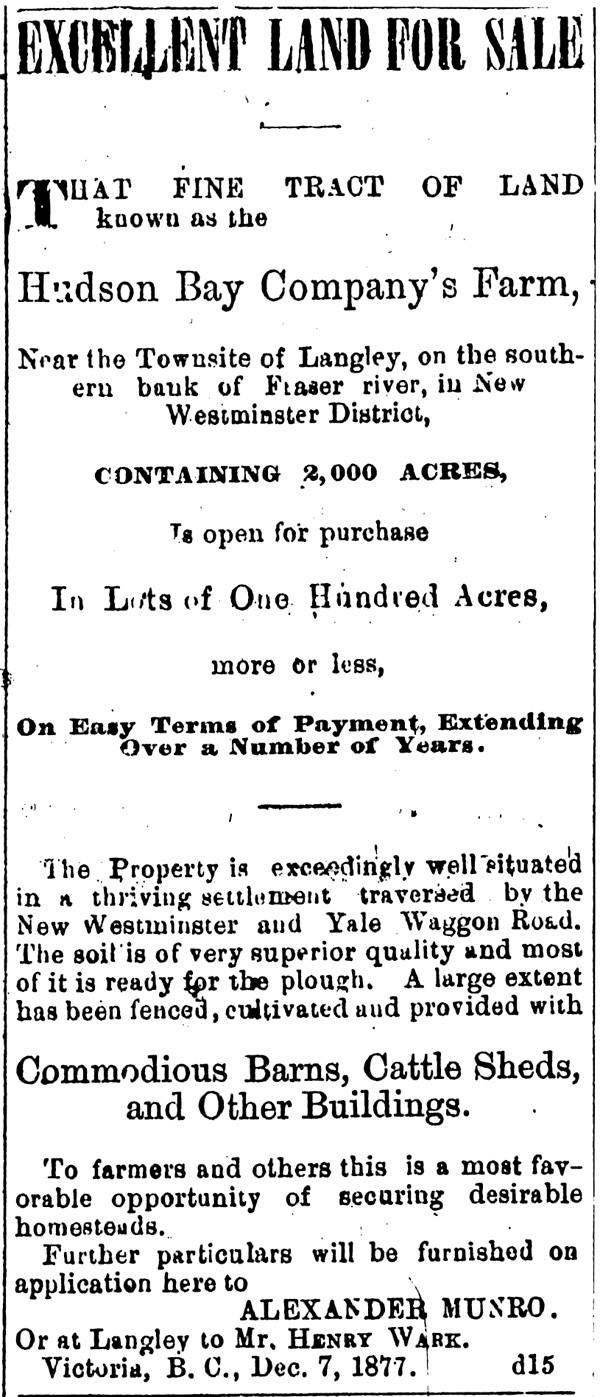

34 Mainland Guardian, 15 December 1877. The first notice of

the intended sale of Langley Farm ran in Victoria and New Westminster

newspapers from the above date until 1 May 1878 when notice of the

auction sale appeared.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

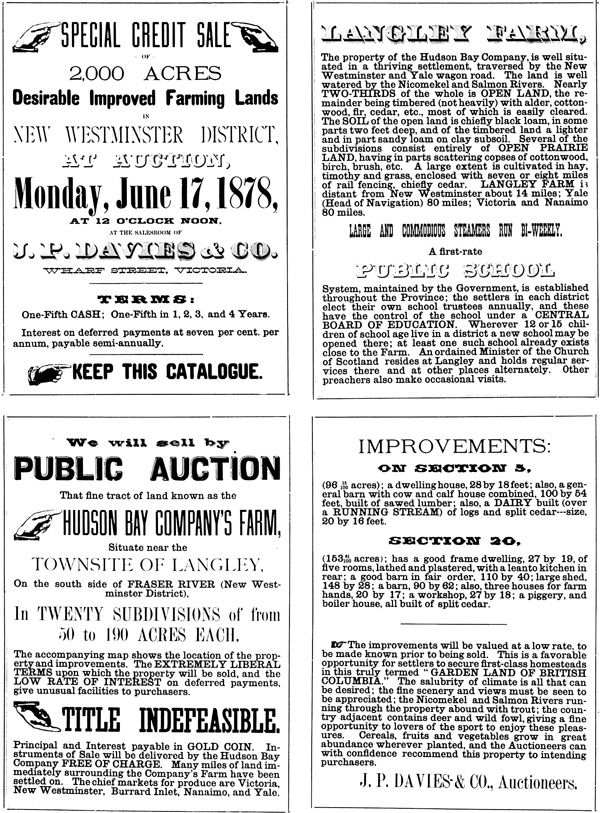

35 A four-page poster put out by the Hudson's Bay Company to advertise

the auction sale of Langley Farm on 17 June 1878.

(Hudson's Bay Company Archives.)

|

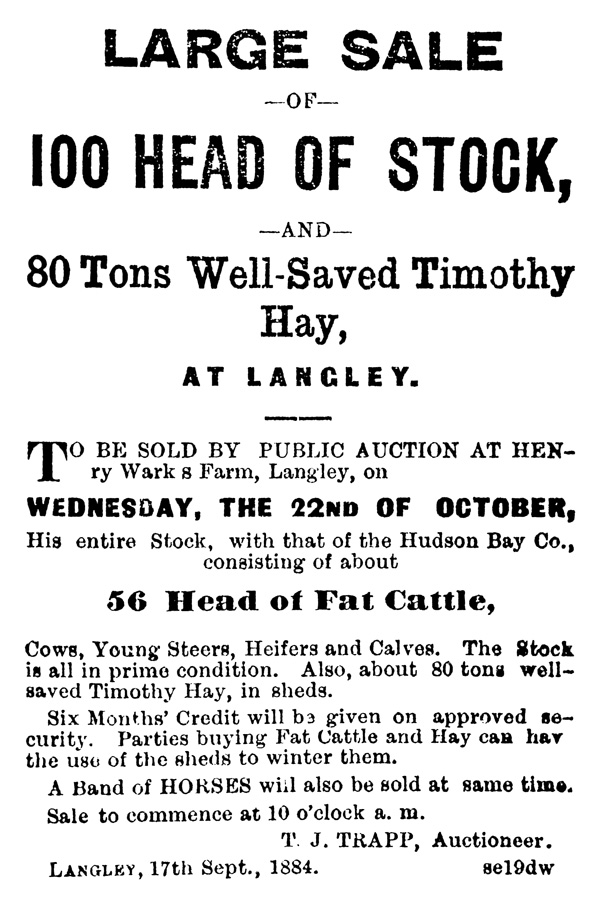

36 Advertisement for the sale of livestock, The Colonist,

Victoria, B.C.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

In February 1886 Victoria contractors Smith and Clark began to build

the new Hudson's Bay Company store at the far northwest corner of lot

19.77 The building containing salesroom and manager's

quarters was ready for occupation the first week in April.78

When the removal of stock to the new store was completed on 15

April,79 the business life of Fort Langley was ended. The

fort property (excluding the site of the new store) with the old store

building and dwelling house was abandoned to the land

department.80

Since the 1878 auction of Langley Farm, the land department had sold

an aggregate of 1,670 acres of land at Langley. Nearly 1,600 acres of

this total were the unsold subdivisions of Langley Farm lots 21 and 22.

The last two sections of the farm were purchased on 15 February 1886,

completing the sale of the whole tract for a sum of

$53,333.17.81 The Company also sold lot 35, 55 acres

preempted by W.F. Tolmie and situated three-quarters of a mile south of

the fort; lot 20, two acres located near "Old Langley or Derby" at the

mouth of the Salmon River, and a 13-acre section of lot 19 on the

northeast corner of the fort property.82 The only remaining

Hudson's Bay Company land at Langley in February 1886 was 187 acres of

the 200-acre lot 19.83 The eventual disposal of Fort Langley

site was considered during the spring of 1886. Munro's description of

the tract suggested its value was small.

No part of the soil is very good. About 30 acres are under

cultivation, but the Crops, usually are small — the soil being

light and mixed with sand. There are some open spaces, used as grazing

ground for the few animals kept at "the Fort". A large part is elevated

and gravelly, producing only under brush and stunted timber of no value.

The northeasterly portion lying low, is frequently overflowed by the

river. This and the rest of the land could be turned to the best account

only by industrious owners or occupants who would keep cows, pigs and

poultry, and make butter, bacon, etc. for sale. In the hands of such

people the property, as a whole, with such trading as they could carry

on there, might be made fairly remunerative.

As stated, the Northeastern part of the land is low; but there the

river is flowing westward has in the course of time deviated trom its

former channel and receded northward on "McMillan Island" ... and thus

there intervenes between the present bed and what formerly was the

Southern Bank of the river (the Northern boundary of the Company's Land)

a barren space or sandspit which is left dry except when overflowed

during freshets. It stretches somewhat beyond the Company's western

boundary, and the only landing place for steamers is a little westward

of the Company's land.84

Given this useless river frontage and the poor quality of the soil,

the maximum value which the Company placed on the land was $6,009. It

decided to sell the property as a whole for its value.85

Meanwhile, some sections of lot 19 were leased for pasturage and the

dwelling house was rented to Otway Wilkie in October 1887.86

On 31 January 1888, 185 acres of the Fort Langley property were sold to

Alexander Mavis at a purchase price of $5,850. Two acres were reserved

for Company use: one acre at the site of the new store, the other 200

yards east on Langley sandspit.87

During its first two years of business the new saleshop was an

ineffectual contender for the village trade. In 1886 it competed with

one opponent who controlled the bulk of the business and subsequently

sold out to two energetic young Canadians named Blackett and White. By

doing a considerable bartering business with the neighbouring farmers,

these men succeeded in building up a trade of approximately $30,000 per

annum.88 In an effort to regain business, the Company

prompted the retirement of Henry Wark and brought in the younger William

Sinclair to manage Langley post from 1 November 1886. Sinclair made some

improvement by reducing the selling price of staples and other articles,

but generally was unable to cope with the opposition.89 He

was transferred to New Caledonia District and replaced by the

exceedingly smart and energetic clerk James M. Drummond.90

The new manager took charge of the Langley store in July 1887 with

instructions to report to Smith "after full consideration on the spot"

what in his opinion was best to be done.91

Drummond's report, which was approved by Smith in December 1887,

suggested a basic change in the Company's mode of conducting business at

Langley. According to its new manager, Langley post could command a

trade of $20,000 per annum if it could arrange, like Blackett and White,

to take payment in produce instead of money. As a marketing agent,

however, the store would need buildings at the wharf for the storage of

hay, grain, butter and so on. The Company determined to make this "new

departure."92 In the spring of 1888 a freight house, ice

house and drive house were constructed at the wharf and arrangements

were made to sell farm produce at Fort Hope.93

The barter business rapidly increased the volume of Hudson's Bay

trade in Fort Langley village. As early as January 1888 the Company

resisted an offer to purchase Blackett and White's business from the

conviction that it could obtain all it required through "good

management."94 While the opposition sold off its entire stock

at reduced prices, Drummond expanded the Company inventory and sold

staples slightly above cost and other goods at a compensating

profit.95 By June 1889 Langley post was turning over a

capital of $11,000 at the rate of 2-1/4 times a year.96 Yet

the greater volume of sales had been achieved at the cost of a smaller

net profit.97 To bring prices up and protect itself from

future competition the Company decided to purchase Blackett and White's

stock and buildings, and a settlement was effected in February

1890.98

37 Fort Langley dwelling house (built in 1872) and farm buildings,

circa 1890. The farm buildings are the former cooper's shop and

saleshop.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

38 Fort Langley buildings as private farm buildings, 1894.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

39 The only surviving Fort Langley building, the former coooper's

shop, 2 May 1925, it later became the focus of the partial

restoration of the fort in 1956.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

Although the absence of competition after February 1890 enabled

Langley saleshop to obtain better prices for goods sold,99

the agricultural character of its trade kept the post in a vulnerable

position. Because the district about Langley contained few large farmers

and the majority of settlers had no reserve to meet a bad season, the

store developed long lists of outstanding balances.100 In the

annual report of trade for outfit 1891, Commissioner R.H. Hall strongly

condemned this method of doing business, stating "the hope of our

mercantile business is not at petty settlements, but in the more central

towns." He suggested "the capita now employed at Langley could be

invested with much better results in the city of New Westminster."

Credit at the post was henceforth reduced to $100 per person with the

stated intention of placing the Company in a position to withdraw from

the village "should it be found necessary to do so."101

Once a policy of retrenchment had been adopted the days of Langley

post were numbered. Drummond opposed the direction affairs were taking

and resigned in March 1892.102 His successor Walter Wilkie

was dismissed nine months later for irregularities in keeping the

accounts.103 When Frank Powell took over the position of

clerk in January 1893104 he was instructed to reduce debts to

$5,000, but flooding of the Fraser valley in the following year made

collection of outstanding accounts slow. The store suffered further from

the credit limit of $100 and the prevailing low prices for farm

produce.105 At length, during a visit of the commissioner to

London in 1895, it was arranged that Langley saleshop should be

closed.106

The business of Langley saleshop was wound up for the end of outfit

1895 which fell on 31 May 1896. Goods suitable to other places were

transferred and the remainder sold at reduced cost. Forced sales of

stock and losses on country produce resulted in a net loss of $5,417, a

sum considered "probably less that would have been experienced

eventually if the post had been carried on."107 The Hudson's

Bay Company's land at Langley was not retained. The one acre east of the

store property was sold to Mrs. Annie Oden in December

1894.108 The store premises were rented for five years; then

the balance of the Hudson's Bay Company property, the one-acre site of

the village stores and warehouses, was sold to Jacob and Jessie Haldi in

July 1901.109

After 69 years of business enterprise at Langley, the Company's

evacuation was definitely anti-climactic. A small footnote in the 1896

closing report which seemed a scant tribute to the historical impact of

Fort Langley noted, "it is regretted that it does not appear practicable

to conduct a remunerative business at this point which is probably the

oldest establishment that the Company has in what is now British

Columbia."110

|