Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 20

The History of Fort Langley, 1827-96

by Mary K. Cullen

The Hudson's Bay Company Goes to the Pacific

The North American fur trade, begun on the shores of the Atlantic,

was slowly but relentlessly driven across the continent. In their

pursuit of furs, traders travelled in a northwesterly direction after

the luxurious pelts of the colder regions and along the waterways of the

Canadian Shield which provided a natural highway into the interior.

Costly transport and supply lines steadily propelled expansion over

wider areas. After 1760 this westward thrust of Montreal traders forced

the Hudson's Bay Company to establish posts at greater distances from

the bay. The North West Company pushed beyond the Hudson Bay watershed

known as Rupert's Land. It founded posts in the fur-rich Athabaska

country and along the river systems of the Pacific Slope.

Before expanding across the Rocky Mountains, the Hudson's Bay Company

determined to undertake a vigorous and expensive campaign in Athabaska,

the source of Nor'western prosperity. With the establishment of Fort

Wedderburn at Lake Athabaska in 1815, the Hudson's Bay Company began a

cut-throat competition designed to extort recognition for its fur trade

and settlement in Rupert's Land. The disastrous results for the London

company in that violent contest prompted a plan to recoup its Athabaska

losses by extending trade to the Pacific.1 By 1821, however,

the North West Company was in desperate financial straits and the

spectre of continuing, costly rivalry impelled both sides to conclude

the struggle.2 On the way out from Fort Wedderburn in the

spring of 1821, the "Bay" men were met by North West traders at Lake

Winnipeg with news that a coalition had taken place between the

companies.3

1 Transcontinental fur trade routes of the Hudson's Bay Company and

North West Company, circa 1820. (click on image for a PDF version)

(Map by S. Epps.)

|

From June 1821 a 21-year agreement placed the trade of the

long-standing rivals in the hands of a remodelled Hudson's Bay

Company.4 As a reward for the merger, the British government

issued a licence5 dated 5 December 1821 granting the new

concern a monopoly, also for 21 years, of the fur trade west of the

Rockies and northwest of Rupert's Land. Exclusive rights in Rupert's

Land continued to apply by virtue of the 1670 "Charter of the Governor

and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson's Bay." The

reconstituted Hudson's Bay Company henceforth controlled an area of more

than three million square miles stretching from the Labrador peninsula

to the Pacific Ocean.6

The organization which directed the trade of the vast territory was a

fusion of North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company elements. By the

indenture of March 1821, final authority for policy was vested in a

London governor and committee, advised by two members from each company.

Administration in North America was initially divided into two

departments, each supervised by a governor on the advice of an annual

council of field officers who were also shareholders. William Williams

was appointed governor of the Southern Department comprising the Hudson

Bay watershed south and east of Fort William. The Northern Department,

which embraced the monopoly territory from Rainy Lake in the east to the

Pacific Ocean in the west, was placed in the charge of George

Simpson.7

The contest between London and Montreal for the entrepôt of the

British fur trade had thus ended in Athabaska. The entrance of the

Hudson's Bay Company info the Pacific trade in 1821 opened the era of

the great London monopoly which dominated the fur trade from Canada to

the Pacific. West of the Rockies where that monopoly was most vigorously

opposed, the aggressive spirit which had typified the Nor'Westers'

transcontinental drive was now united with the discipline and efficiency

of George Simpson in one of the most exciting and assertive phases of

the British fur trade in North America.

In 1821 Britain's principal contestants for the fur trade in Pacific

North America were Russia and the United States. Russian commerce was

the indirect result of scientific expeditions on the eastern fringes of

Asia. Fine peltries brought to St. Petersburg by survivors of the

Bering-Chirikov expedition of 1746 prompted several traders to exploit

the American coast. Among the more efficient contenders was a group

which in 1799 received from Czar Paul I a charter granting their company

a 20-year monopoly on the coast of America north of 55° north

latitude and authority to extend its control southward into unoccupied

territory.8 The chartered Russian American Company began an

active program of North American expansion. Alexander Baranov, its chief

manager from 1799 until 1818, aimed to develop a new empire on the

shores of the Pacific. He established a settlement at Sitka in 1799

(rebuilt in 1804 as New Archangel) and in 1812 he built Fort Ross in

California as a fur-trading centre and source of food supplies for the

northern colonies. The company maintained a station in the Farallons and

it regarded the Hawaiian Islands as a potential field of

commerce.9

Counterforce to this regime were both British and American maritime

fur traders. After Captain James Cook's exploration of the Northwest

Coast between 1776 and 1779, his crew's sale of sea otter in the China

market sparked international interest in the maritime trade. At the

outset nearly 35 British ships dominated the trade,10 but

from 1789 onward, American vessels principally from Boston also culled

the coast. When Britain entered the Napoleonic Wars in 1793, the

maritime business effectively became the monopoly of the city of

Boston.11

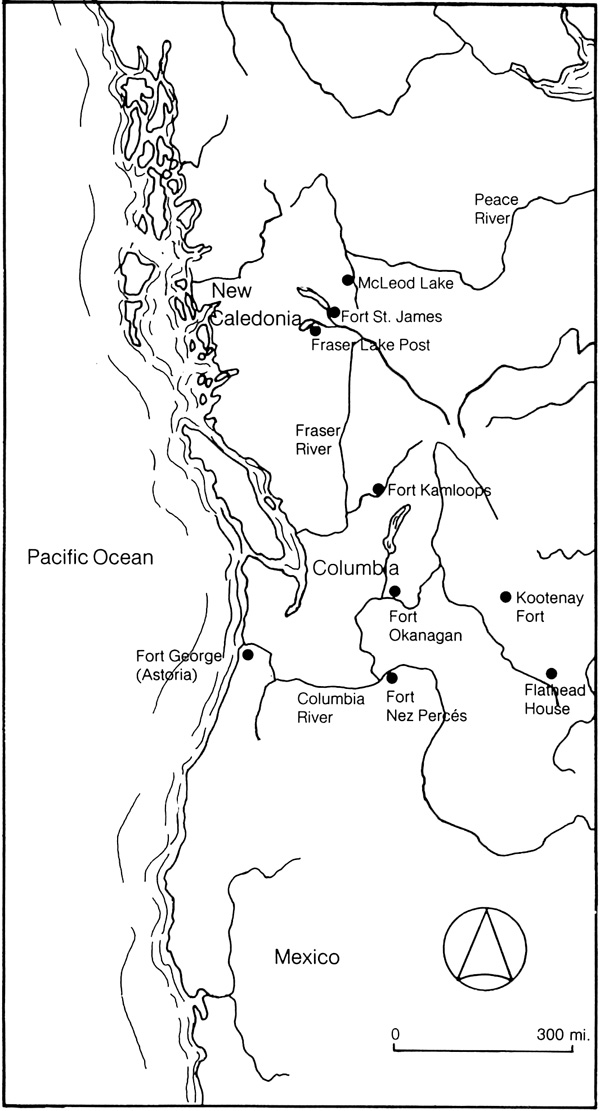

2 North West Company posts on the Pacific Slope, 1821.

(Map by S. Epps.)

|

The Boston merchants used the sea otter as a medium of exchange to

purchase Oriental goods for sale in New England. Their trade never

reached the stage of unification, but was merely a series of individual

efforts which, as sea otter became scarce and competition keen, changed

its focus to sandalwood, land furs and other types of

exchange.12 In this latter phase of the maritime fur trade

the Yankee petty traders became a particular source of annoyance to the

Russian American Company. To meet the decrease in sea otter skins the

American ships offered to sell goods to the Russians and freight their

furs to China; in their turn the Russian settlements, far from their

homeland, came to depend on the Bostonians for many essential

supplies.13 Unfortunately, the Americans brought more than

Russian supplies north. They also traded liquor, rifles and ammunition

directly with northern Indians for sea otter and land pelts. The Russian

concern was not only that this unregulated trade debauched the native

people and endangered Russian servants, but also that it forced the

Russian American Company to pay higher prices for furs.14

When the Russian government renewed the Russian American Company's

charter in 1821, it moved to protect the company against the free

traders. The revised charter, dated 13 September 1821, extended Russian

sovereignty to the "shores of northwestern America... commencing from

the northern point of the Island of Vancouver under 51° north

latitude to Berhing Straits and beyond them."15 A cordon

sanitaire was created around this area by an imperial ukase which

warned all foreigners not to approach within 100 Italian miles of the

Russian coast.16 The ukase was primarily directed against the

Americans, but it also struck deeply at British interests, which since

1805 were firmly established inland on the Pacific Slope.

While Russians and Americans canvassed the Northwest Coast, British

fur traders returned to the Pacific, not by sea, but overland from

Canada. Following the transcontinental journey made by Alexander

Mackenzie in 1793, Nor'Westers John Stuart and Simon Fraser established

a fort at McLeod Lake, the first British trading post west of the

Rockies, in 1805.17 Three years later Fraser descended the

river to be named after him while David Thompson explored southward in

the Columbia River basin. In an abortive American challenge for the

inland fur trade, John Jacob Astor's Pacific Fur Company built Astoria

at the mouth of the Columbia in 1811, only to be bought out by the

Canadians, who were supported by British naval power during the War of

1812.18 The Montreal traders established headquarters at

Astoria (later Fort George) and subsequently dominated trade in the

Pacific interior.

Under the treaty of Ghent in 1814, which stipulated a return to the

status quo ante bellum, Fort George was formally restored to

American jurisdiction.19 Since Astor was unprepared to

reoccupy the fort and regional sovereignty remained in doubt, the

Nor'Westers continued in occupation. The Convention of 1818 accepted the

49th parallel as the boundary east of the Rockies, but British and

American negotiators failed to agree on a transmontane partition. The

result was a ten-year agreement whereby the territory between California

and the indeterminate claims of Russian America was to be left open to

the subjects of both nations.20 This joint occupancy west of

the Rockies meant the licence of 1821 could not prejudice the trade

rights of American citizens.21 It simply concentrated all

British rights to the Oregon trade on the reconstituted Hudson's Bay

Company.

In 1821 the British fur trade on the Pacific Slope therefore faced a

dual political situation: on the one hand Russia was encroaching on an

area of potential British continental expansion; on the other hand,

throughout the vast area north of 42° north latitude the United

States competed with the sanction of international treaty. The movements

of these two powers were to exert a constant influence in the

development of Hudson's Bay Company policy for the Pacific. In its most

intimate aspects, however, that policy was initially shaped by the

previous enterprise of the North West Company.

The Nor'Westers organized their transmontane posts around the two

principal water systems of the Pacific Slope — the Fraser and

Columbia rivers. In modern terms their activity encompassed an area

stretching from California to northern British Columbia. The northern

part of this region around the upper Fraser was known as New Caledonia.

To the south, with its headquarters at the mouth of the Columbia River,

was the Columbia District.

New Caledonia was viewed by both North West and Hudson's Bay men as

an extension of the rich Athabaska region. At the time of the coalition

it was still vaguely defined and poorly exploited. The district included

four posts: McLeod Lake, Fort St. James on Stuart Lake, Fraser Lake post

and Fort George at the confluence of the Stuart and Fraser rivers.

George Simpson, writing in his Athabaska journal, estimated there were

about "one hundred packs" taken from New Caledonia

annually.22 These fur returns were generally sent across the

Rockies to Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabaska, there joining other

brigades bound for Fort William and Montreal. District supplies were

also transported inland via the long eastern route.

The Columbia District, which contained seven posts, embraced the

whole vast watershed of the Columbia and extended as far north as the

Thompson River. Six establishments were south of the 49th parallel: Fort

George, originally Astoria, built by Astor's Pacific Fur Company in

1811; Fort Nez Percés or Walla Walla; Spokane House; Flathead House;

Kootenay Fort, and Fort Okanagan. Located northward on the Thompson was

Fort Kamloops. The Columbia District sent its furs and received its

supplies by ship at Fort George. The immense size of the district made

it expensive to maintain and its fur returns were proportionately

inconsiderable.23

After 1813 the commanding position of the North West Company in the

Pacific inland trade induced some of the Columbia traders to indulge

their taste for luxury by importing such fanciful items as ostrich

plumes, velvets and silk stockings.24 Their extravagance

contributed to substantial losses in the southern district. The

profitability of the transmontane venture as a whole was still more

acutely limited by the want of an effective system of marketing and

transportation.

China was the natural outlet for the furs of the Pacific Northwest,

but business there was complicated by the exclusive British trading

privileges of the East India Company. The North West Company was able to

sell furs at Canton but it could not take away a return cargo of tea or

other Chinese produce. It tried to overcome this obstacle by employing

the Boston firm of Perkins and Company, which under the protection of

the American flag would transport supplies to the Columbia and sell the

returns in Canton. The system was unsatisfactory since Perkins and

Company received nearly one-fourth of the proceeds and the prices paid

for Columbia beaver at Canton were less than the London market

value.25

Transportation expenses provided the impetus for North West Company

expansion to the Pacific and ruined the enterprise thereafter. In

searching for a route from Canada to the Pacific, Alexander Mackenzie

had hoped to tie the continental fur trade to China and provide the

overextended North West Company with access to its more western

districts from the Pacific Ocean.26 His overland route and

the subsequent water explorations of Simon Fraser failed to produce a

navigable communication with the interior.27 Meanwhile, the

expansion of posts into New Caledonia prompted by these explorations

made a shorter supply system even more essential.

The search for a Pacific supply line was continued by John Stuart,

who in 1813 discovered a land and water route from New Caledonia to Fort

George following the Fraser River 130 miles south, then commencing

overland to join the Columbia River at Fort Okanagan.28 For

unknown reasons, full-scale use of the western brigade trail was

delayed29 until Stuart reassumed charge of New Caledonia in

January 1821.30 A few weeks after the union of the two

companies (an event of which he was not immediately aware), Stuart

established Fort Alexandria at the point of transfer from the Fraser

River overland and purchased horses for the journey from Fort Alexandria

to Fort Okanagan.31 Within a year the Pacific link was

functioning smoothly.32

At the time of the coalition, the North West Company had thus begun

to view their Pacific enterprise as a single operation with one centre

of administration and transportation. The successful solution to New

Caledonia's communication problem promised future savings in labour and

expense. Yet in retrospect, a dual system of transportation combined

with an uncertain market and extravagant importations had made the

Nor'Westers' Pacific venture a costly project, incommensurate in its

returns.

In the light of North West Company experience, the remodelled

Hudson's Bay Company commenced trade in the Pacific cordillera with some

caution. There was hope that the Pacific fur trade might eventually be

profitable from the Fraser valley northward,33 but the Hudson

Bay-oriented Company saw New Caledonia as an extension of Rupert's Land

rather than a separate entity in itself. One of the first acts of the

Northern Council was therefore to reject Stuart's western supply route

in favor of transporting the New Caledonia outfit from York

Factory.34 Little was expected in the way of returns from the

ill-reputed Columbia department; instead the Company regarded the region

as a buffer for the north "as if it does not realize profits no loss is

likely to be incurred thereby and it serves to check opposition from the

Americans."35

The potential of the Columbia valley as a frontier for the northern

posts as well as the prospect of diplomatic advantage impelled the

Hudson's Bay Company to take immediate measures to strengthen its

Columbia position. The arrangement with Perkins and Company was replaced

by a system of supply from England in the Company's ships and the sale

of Columbia returns on the European market.36 Fort George was

ordered to be abandoned, not only since it had been formally restored to

the Americans in 1818, but also because it was situated on the south

side of the Columbia River, a region expected to be awarded to the

United States in any boundary agreement. In its place the Company

ordered the construction of a new post on the north side of the river as

a means of firmly establishing title to that area.37 Finally,

it proposed to scour the country to the south and east of the Columbia

and appointed trapping expeditions under competent leaders "to get as

much out of the Snake country as possible for the next few

years."38

Long-term policy for the trade of the Pacific Northwest remained to

be formulated. The London governor and committee, as directors of a

primarily continental enterprise, originally planned their Pacific

expansion in terms of an extension of trading posts north and west of

the Fraser River.39 Interest in the potential of a coastal

shipping trade as well was prompted by the Russo-American convention of

17 April 1824. Through a similar treaty concluded with Britain a year

later, Russia agreed to confine its activity north of 54° north

latitude and to open Russian coastal waters to British vessels for ten

years.40 Anticipating this agreement in July 1824, the

governor and committee authorized a ship to explore the trading

possibilities along the coast.41 A comprehensive plan of

action for continent and coast awaited the visit of young George Simpson

and his report on the Pacific.

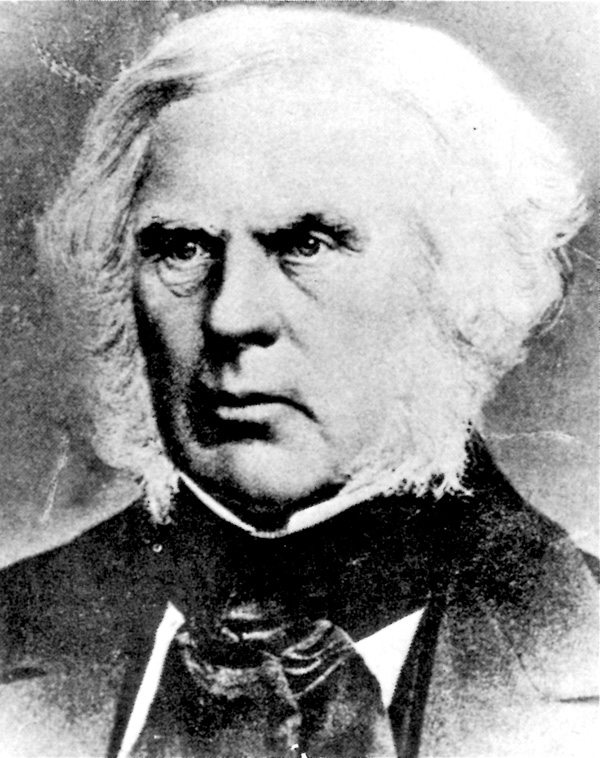

The last stages of the Athabaska campaign had clearly revealed

Simpson's potential for leadership. Then just 33 years old42

and with scarcely a year in the service, he had made himself familiar

with every detail of the Athabaska trade and still displayed the

perspective and imagination required in directing the affairs of a large

corporation. As governor of the Northern Department, after 1821 Simpson

was influential in the reorganization of the fur trade in Rupert's Land.

His complete removal of duplicate trading posts and personnel of the two

old companies was followed by an insistence on economy at every turn. He

approached his work with an inquisitiveness and fervour which demanded

personal contact with problems. Simpson travelled tirelessly across the

Company domain, probing and investigating such vital matters as

transport and communications. As a master of men and a shrewd judge of

character, the governor exercised increasingly autocratic control over

his council. Still, he knew his men well and took care to learn from

them.43 In 1824 he brought his enthusiastic, revitalizing

spirit to Britain's Pacific fur trade.

Before his departure from York Factory on 15 August, Simpson prompted

the appointment in council of John McLoughlin as chief factor

superintending the area west of the Rockies, which the Company referred

to as the Columbia Department.44 McLoughlin had served the

North West Company since 1803 and had participated in the negotiations

for coalition. Physically "the Doctor" (so-called by his colleagues in

deference to his early medical training) was an imposing figure; a giant

of a man with a rangy mane of white hair, sans toilette he conveyed

"a good idea of the highway men of former Days."45 He had

strong views and, though occasionally exercising a temper, was

nonetheless an experienced trader with considerable administrative

ability. McLoughlin left York for the Columbia three weeks before

Simpson only to be overtaken by the governor travelling at his usual

prodigious pace.

Simpson and his new superintendent arrived at Fort George near the

mouth of the Columbia on 8 November 1824, a record 84-day journey from

Hudson Bay.46 During the next five months the governor

examined and assessed the Pacific trade in all its aspects. Many basic

improvements he inaugurated unilaterally and these changes together with

further recommendations of policy he embodied in a comprehensive report

to the London committee.47

Simpson's first impression was one of utter extravagance and

mismanagement. In his thorough manner he rapidly moved to put affairs on

a more businesslike footing. He insisted that the Columbia supplies must

be cut from 645 to 200 pieces,48 that agriculture must

lighten the expense of imported provisions49 and that the

Columbia staff be reduced from the existing total of 151 to

82.50 Almost nothing was known of the coast, its navigation

or resources. Within a few days of his arrival Simpson dispatched Chief

Trader James McMillan with a party of 40 men to acquire a thorough

knowledge of the communication and country of the Fraser

River.51

In the meantime the governor began to take an enlarged view of

Company affairs west of the mountains. Though like the London committee

he had initially viewed the northern Pacific Slope as a projection of

Rupert's Land,52 Simpson's personal visit to the Columbia

impressed him with the distinctive merits of the entire Pacific trade.

His fascination with the potential of the coast and its interior country

led him to speculate that commerce there could "not only be made to

rival, but to yield double the profit that any other part of North

America does."53 For purposes of administration and supply

Simpson now saw the whole Pacific business functioning as a unit. New

Caledonia must be joined to the Columbia and a diversified coasting

trade run in conjunction with the inland business. Further, to end

Russian and particularly American competition, an arrangement must be

concluded with the East India Company, tying British trade on the

Pacific Slope to the China market.54

At the centre of Simpson's thinking was the idea of establishing the

grand Pacific depot at the mouth of the Fraser River. A move north might

ultimately be necessary if the Americans should settle at Fort George,

but whether they came to the Columbia or not, the Fraser seemed to

possess other advantages, Its situation was central for the most

lucrative area of the coastal fur trade and for British expansion

northward.55 Yet effective inland transportation seemed to be

the motivating consideration. During his brief visit in the Columbia,

Simpson came to the optimistic conclusion that the Fraser was a

navigable river which could serve as New Caledonia's much-needed access

to the Pacific. This assumption he apparently based on Indian

reports56 and his own personal assessment of the 1808

Fraser-Stuart journey which he stated was executed safely "in the months

of June and July when the waves are at their full height and when the

Columbia River is impassible."57 Simpson further suggested

that McMillan's exploratory expedition to the Fraser River successfully

tested its navigability.58

3 George Simpson, governor of the Northern Department of Rupert's

Land, 1821-26; governor in chief of all Hudson's Bay company territory

in North America, 1826-60.

(Hudson's Bay Company Archives.)

|

4 John McLoughlin, superintendent of the Columbia Department,

1824-45.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

McMillan was a man of experience in the Pacific, having been

associated with David Thompson 15 years earlier on the upper waters of

the Columbia. The former Nor'Wester became a chief trader of the

Hudson's Bay Company in 1821 and served at Red River until he was chosen

to accompany Simpson to the Columbia.59 On 19 November 1824

McMillan led an expedition of 40 men from Fort George north. The party

portaged from the Columbia River to Puget Sound and thence followed the

channels and bays of the sound to a small stream which fell into

Boundary Bay. Ascending that stream (the Nicomekl), they then made a

portage to another small river, the Salmon, which emptied into the

Fraser about 20 miles above its mouth.60 At this point the

Fraser was a "fine large Stream navigable... by craft of about One

Hundred Tons."61 The party travelled, in all, nearly 60 miles

upstream in the course of which they saw neither shoal nor rapid. Ice in

the upper part of the river prevented them from proceeding much further,

but a local Indian tribe62 informed McMillan and his men that

the Fraser as far as the Thompson River was "navigable with a strong

current."63

The fact that McMillan only managed to examine the lower reaches of

the Fraser did not alter Simpson's enthusiasm for that river as his

Company's main commercial highway and site of its Pacific depot. In

addition to McMillan's favourable report on navigation, the governor

submitted other observations made by the reconnaissance party which were

conducive to establishing headquarters at the Fraser. Contrary to

prevalent fears of the treacherous character of coastal Indians, the

peoples inhabiting the lower Fraser proved friendly and seemed

"delighted" at the prospect of having the whites settle among

them.64 Throughout the river valley the soil was generally

rich and fertile, timber was prodigious and good situations for the site

of an establishment existed in almost every reach. McMillan particularly

recommended the entrance of the small Salmon River falling in from the

south which he had followed in gaining the main stream. There an

extensive meadow existed where cattle could be raised and food stuffs

cultivated and the river alone had salmon and sturgeon sufficient for

the maintenance of a post.65

Simpson proposed a scheme for the establishment of the Fraser River

depot which was allied with a bold initiative in the coastal trade. A

vessel intended for the China trade would leave England in November

1825, reach Fort George in July 1826, deliver the outfit and take on the

furs for China. After disposing of the furs in Canton, the vessel would

take on a cargo of Chinese produce and sell it in Lima, Acapulco or some

other port where it would pick up the English outfit. In July 1827 it

would return with the trade goods for the Columbia. Embarking with the

furs of the past season, it would then proceed with people, goods and

stores in company with a small coastal vessel (to be built in the

country) to the Fraser River. The two ships would remain there until 1

November by which time the establishment would be completed. Then the

larger vessel would be dispatched for China while the smaller one would

proceed along the coast on a trading expedition, touching at the Russian

settlement in Norfolk Sound to see if any business could be done there.

Finally, with the arrival of the inland brigades in the spring of 1828,

the whole machine would be put in motion with the depot at the Fraser

River as its focal point.66

The conviction that the Fraser must soon become the nucleus of the

Columbia department was reflected in Simpson's interim arrangements for

the Pacific trade. According to instructions from the governor and

committee in London, Fort George was abandoned and a new depot named

Fort Vancouver was built on the north side of the Columbia. Though as a

depot the post was inconveniently situated 75 miles from the river mouth

and 1-1/4 miles from the riverbank, Simpson insisted Fort Vancouver was

merely a "secondary establishment"67 which would serve

temporarily as McLaughlin's headquarters but whose greater purpose would

be farming.68 Because he felt there were advantages in

transacting business from one depot, Simpson instructed his Pacific

personnel to re-employ Stuart's brigade trail between New Caledonia and

the Columbia "until the mouth of the Fraser's River is

established."69 On his return east the governor secured

approbation for these arrangements from the annual council at York

Factory in July.70 The entire Pacific strategy required the

final sanction of the governor and committee in London and after council

Simpson departed for England "to give information on many points that

might be essential to its future interests."71

December 1825 found Simpson in London conferring with the governor

and committee. He had scarcely begun to discuss his Fraser River

strategy when he discovered the Company was more immediately concerned

with securing a strong case against withdrawal from the Columbia. The

joint occupation agreement between Great Britain and the United States

would expire in 1828 and it was possible that a boundary might be agreed

on before that date. If the Columbia basin was to be used as a frontier

for the north, the Company had to obtain the Columbia River as the

boundary. Simpson, fresh from his journey to the Pacific, was the

obvious person to present the case. Completely reversing his argument in

favour of the Fraser as a business highway, he replied to a series of

questions from the British Foreign Office by emphatically denying that

the Fraser "affords a communication by which the interior Country can be

supplied from the Coast, or that it can be depended on as an outlet for

the returns of the interior."72 He added that "the only

certain outlet for the Company's trade" was the Columbia River; if its

navigation was not free, the Company "must abandon and curtail their

trade in some parts, and probably be constrained to relinquish it on the

West side of the Rocky Mountains altogether."73

Foreign Office requirements postponed consideration of the Fraser

river strategy, but did not preclude it. A few weeks after Simpson's

testimony, the governor and committee approved his plans for including

New Caledonia within the Columbia Department and extending the trade on

the coast as well as in the interior.74 They directed the

Fraser River settlement to be established "next season if possible,"

adding "from the central situation of Frazers River we think it probable

that it will be found to be the proper place for the principle

depot."75 In two respects, however, they qualified Simpson's

scheme. First of all, marginally successful consignments to Canton in

1824 and 1825 made the committee wary of using the China market for the

whole of its Pacific returns.76 Secondly, since McMillan had

explored only the lower reaches of the Fraser, final commitment to a

Fraser depot was reserved until the Company had fully ascertained

"whether the navigation of the River is favorable to the Plan of making

it the principal communication with the interior."77

Without deviating greatly from Simpson's original recommendations,

the London discussions thus determined Hudson's Bay Company Pacific

priorities to be an establishment at the Fraser and the inauguration of

a coasting trade. McMillan was chosen to build the new Fraser River post

which was to be named Fort Langley in honor of Thomas Langley, a

director of the Company.78 According to Simpson's suggestion,

the coasting trade was to be inaugurated with Fort Langley and, to

ensure completion of the ship currently on the stocks at Fort Vancouver,

the commencement date for both was set for the spring of

1827.79 In the interval new efforts were to be undertaken to

determine the navigability of the Fraser.

During the summer of 1826 Archibald McDonald,80 clerk and

officer in charge of the Thompson River District, went by canoe along

the Thompson from Kamloops to the Fraser and examined the main stream by

land for about eight miles south. In a pessimistic assessment he

suggested "the nature of those two rivers, rolling down with great

rapidity in a narrow bed between immense mountains generally speaking

render their ascent most laborious, and in places in the main river

perhaps impossible but at low water."81 Chief Factor William

Connolly, in charge of New Caledonia District, had James Murray Yale

explore the Fraser from Fort Alexandria south to the mouth of the

Thompson. Yale reported that in some sections of the river which could

not be avoided by portage, the water rushed with such impetuosity that

bark canoes could not resist its action. Still he considered that "in

moderate waters (i.e. before their rise in the Spring and after they

have subsided in the Summer) the Navigation would not be attended with

much danger."82

These conflicting statements meant the practicability of

communication was still in doubt when on 27 June 1827 the expedition set

out to establish Fort Langley. In London the governor and committee

continued to reserve judgement on the subject of the principal depot.

Back at York Factory, however, the indomitable Simpson was confident

that his plans for the Fraser could be carried out. He had read the

reports of the different parties that had explored the Fraser and had

come to the conclusion that "the navigation will be found safe and good

if the passage be made at the proper season.83 In July he

instructed McLoughlin that New Caledonia should be outfitted by way of

the Fraser the following season.84 "Fort Langley," Simpson

concluded, "will be the Establishment of the next greatest importance to

Fort Vancouver and in the course of a few years I have little doubt it

will become our principal Depot for the country west of the

Mountains."85

|