|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 20

The History of Fort Langley, 1827-96

by Mary K. Cullen

Gold Rush: Climax and Turning Point of Fort Langley's Career

The endurance of the commercial prominence which Fort Langley

achieved as a trading and transporting point in the 1850s was predicated

on many factors, but on none more fundamental than the continuance of

the fur trade. As long as the vast territory of the Pacific mainland was

essentially an isolated preserve of the Hudson's Bay Company with a

total non-Indian population of less than 200, fur resources and the

logistics of supply determined the important foci of activity. When the

Fraser River gold rush rapidly altered the number and distribution of

people and centres, the fur trade collapsed and the economic life of

Fort Langley was profoundly changed. During the months of 1858 which

brought about this change, Langley climaxed its career by becoming the

starting point for the gold rush and the inauguration place of a British

colony on the Pacific mainland.

Discovery of gold on the Flathead River in Oregon prompted Company

discussion on the impact of a major northern discovery almost three

years before the famous Fraser River rush. In August 1855 Douglas

predicted that "the streams north of the Columbia will be found equally

rich in gold, and probably the day is not distant when the great

discovery will be made."1 Then and later there was

apprehension that the fur trade would suffer from the effects of these

discoveries, but a more persistent concern was that the Company, by

supplying the miners, might increase the value of its general

returns.2 In March 1856 Douglas wrote to Simpson, "the

chances of our making a profitable trade will be greater just in

proportion as the expense of transport decreases, and the locality of

the Gold diggings is brought nearer our Depot at Fort

Langley."3

During the spring of 1856, gold was found in several parts of the

Thompson River District and Yale reported small quantities of the metal

in the bed of the Coquihalla River near Fort Hope.4 New

discoveries made by native peoples throughout the following year

provided assurance of gold being found in considerable quantities in the

British interior.5 The Company post at Kamloops traded 49

ounces of gold dust from Indian diggers in August 1857.6 Both

Indians and fur traders moved to monopolize the gold deposits for their

own benefit, the Indians by open antipathy to foreign

adventurers,7 the Company by legal and practical measures to

cut off American competition for the gold trade.

The Hudson's Bay Company had no legal governing authority on the

Pacific mainland, but for years its board of management had skillfully

acted to protect life and property and to contain crises between the

native people and the whites. Douglas now attempted to protect the

Company from American entrepreneurs in the same paternalistic fashion.

In November he wrote the officer at Kamloops that "the Company having

the exclusive right of trading with Indians on the West side of the

mountains, no other person can lawfully carry on trade or erect trading

establishments within the British territory and you may warn them off on

any attempt to do so."8 As governor of Vancouver Island and

nearest British official within thousands of miles, Douglas also issued

a proclamation declaring the rights of the crown to all gold found in

its natural place of deposit and forbidding gold seekers unless duly

authorized by Her Majesty's colonial government.9

The practical step of preparing and operating supply routes to the

mines put the Hudson's Bay Company in the best position to dominate

future events. For this important task Douglas enlisted the trailblazing

aptitude and depot experience of Fort Langley. Yale advised that goods

might be forwarded by way of the 13-mile Douglas Portage as far as the

junction of the Thompson and Fraser.10 A plan was therefore

devised to have a transport corps of two officers, ten white men and

several Indians to conduct a continuous supply service by this

route.11 The machinery for the transport operation involved

two lines of river craft: canoes for use between the Thompson and the

upper end of the rapids of the Fraser River and batteaux for 130 miles

from the lower end of the rapids to Langley.12 The journey

through Douglas Portage was to be made on foot. Langley carpenters built

the batteaux in January and the transport service commenced a month

later.13

Two trips were made by the Fraser before the annual rise in the river

forced the transfer of supply services to the Fort Hope road. Douglas

was at Fort Langley on 15 February to dispatch the first supply party

for the interior. The expedition, in clerk George Simpson's charge, took

one loaded batteaux as far as old Fort Yale, transported the property

overland by Douglas Portage to Spuzzum immediately above the falls, and

thence went by canoe to Tecungean (now Lytton) where the Thompson met

the Fraser. There the goods were received by a horse brigade from

Kamloops.14 On a second inland trip in March, an enlarged

Fort Langley party started building a new post at the forks, to be

called Fort Dallas (in November that year its name was changed to

Lytton)15 The old buildings at Fort Yale, which had been

abandoned after Peers's road to Fort Hope became the brigade trail, were

renewed and a stack of provisions were laid up there and at Fort Dallas

for the spring trade.16

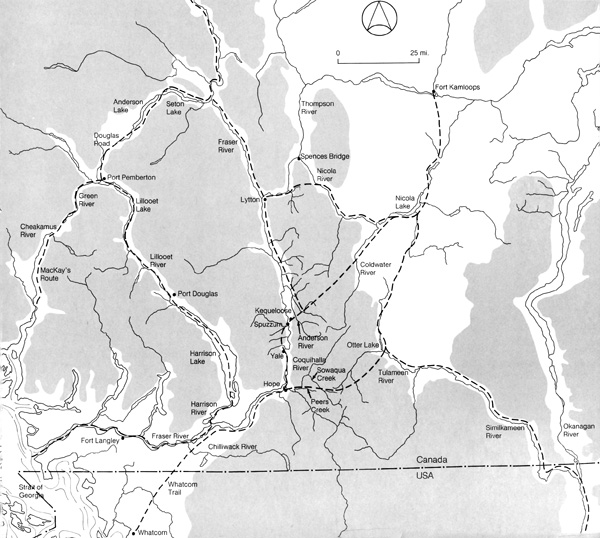

16 Brigade routes to the Fraser River gold fields. Gray indicates major

mountainous areas. (click on image for a PDF version)

(Map by K. Gillies)

|

Throughout these preparations the Company monitored the extent of

possible gold deposits. Since the Indian population had commenced mining

on the Thompson in July, there had been a total gold yield of 1,000

ounces. Allowing for the disproportion in the number and skill of the

mining population in the two countries, the return was relatively small

compared to the California mines which during the same initial

eight-month period yielded 150,000 ounces.17 The conclusion

seemed obvious: these statistics would not attract the white miner, but

when news spread that 800 ounces of gold had been sent from Victoria to

the San Francisco mint in February,18 the rush to Fraser

River was on.

The great influx of adventurers started in April when the American

steamer Commodore arrived in Victoria with 455 passengers from

San Franciso. There were double that number in May, more than 7,000 in

June, 7,000 in July and at least 8,000 more who made their way overland.

By August when the fever began to subside, the registered departures

from San Francisco had totalled almost 30,000. Frequently, ships carried

more than the officially accepted number. The Sierra Nevada,

which landed 1,900 people in Victoria on 1 July, had sailed from San

Francisco the previous month with a "maximum" of 900

passengers.19

Since the first focus of mining activity was at the junction of the

Thompson and Fraser rivers, whether would-be prospectors came overland

or by boat from Victoria, Fort Langley was for all the last point before

the gold district. As such the fort became the administrative and

policing centre of British and Company interests. On 8 May 1858 Douglas

issued a proclamation asserting the exclusive trading rights of the

Hudson's Bay Company, forbidding British and foreign trade on the

mainland and requiring all river craft of any sort to purchase a licence

from the Company and a sufferance from the proper customs officer at

Victoria.20 To enforce these regulations Douglas persuaded

the naval authorities to station the gunboat Satellite at the

mouth of the Fraser and to anchor her launch and gig off Langley. Two

revenue officers at Langley seized contraband goods and took unlicensed

canoes into custody.21

In addition to its policing responsibilities, Langley had already

assumed charge of the forwarding business to the mines and now became

itself a major retail outlet. The Fort Langley saleshop was doing a

brisk business in May and had received 336 ounces of gold dust and about

$5,000 cash since the beginning of March.22 Articles in

demand were blankets and woollen clothing, tinware such as pots and

frying pans, various mining tools including pans and pickaxes, and

provisions, principally flour, bacon, beans and molasses. Food was

scarce but the Company tried to keep it inexpensive. Flour sold at nine

dollars per 100-pound sack and sugar at 16 cents a pound. In

anticipation of greater scarcity of food in the winter of 1858-59, the

Company directed its traders to secure as many dried salmon as

possible.23

To the average miner, American in extraction and used to the

undisciplined free enterprise of California mining towns, dealing at the

Hudson's Bay Company fort store was an unusual experience. The editor of

the Alta California recorded in detail his observations of the

regimentation of business at Langley saleshop.

At six o'clock in the morning the massive bolts and bars are

unlocked from the entrances to the stockade which surrounds the

buildings of the Hudson's Bay Company .... At a later hour in the

morning the door of the sales-room is opened, in the loft next to the

northeastward of the chief trader's residence, and the business of the

day begins. The door is scarcely opened when the small space allotted to

customers inside the building is filed with people, and from that moment

trade is unceasing, and a continuous stream of coin flows into the till

of the Company until noon, when a bell rings and business ceases at

once. Everybody leaves the store-house, the doors are closed, and all

hands go to dinner. At the end of an hour business is resumed again, and

the same dull and monotonous routine is gone through with until six p.m.

when again trade is brought to a dead halt, the crowd disperses, and the

business portion of the day is ended.

The conduct of business was not only routine, but also quaint and out

of fashion. Amused, the writer continued,

Inside this trading warehouse there is a look of venerable

antiquity that it would be difficult to match in any other portion of

the world today. The scales used for weighing out the wet goods are the

old style balances, with ponderous upright and beam, and capacious trays

for the reception of merchandise, suspended from the one end, and one

for the weights from the other. Everything else about the establishment

is in keeping with this, and business is transacted exactly as it used

to be in the quaint old towns of the thriving Knickerbockers and early

tradespeople of staid New England.

A bottle of whiskey, or "Hudson's Bay lightning," as it is not

inappropriately called, when sold to a purchaser, is first carefully

corked, then a string tied around the neck, and a loop formed so that it

may be conveniently suspended from the finger, then a piece of paper is

carefully wrapped around it, and the customer receives possession of his

property ... it is to such customs that Young America applies the

expressive title of "old fogyism."24

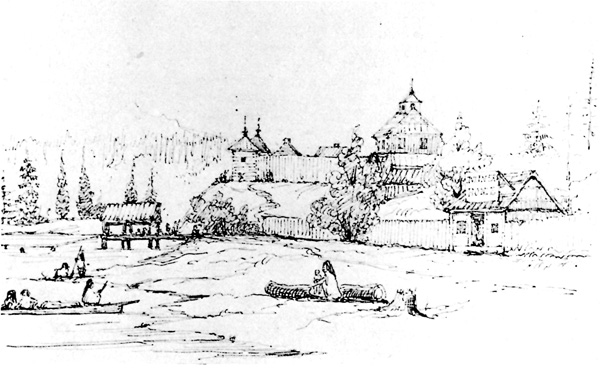

17 Fort Langley, 24 May 1858, from the private sketchbook of Alexander

Grant Dallas.

(Dr. O.V. Briscoe, London, England.)

|

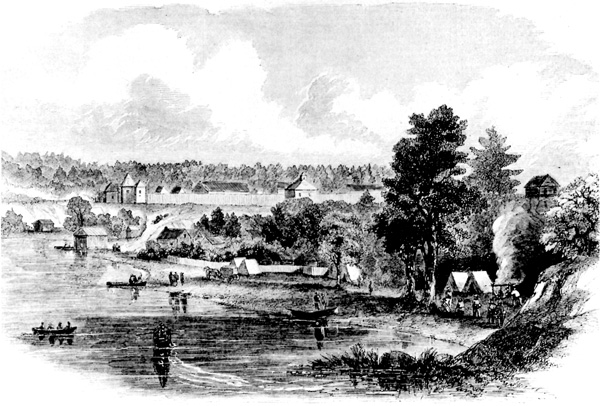

18 "Fort Langley, Frazer's River," Harper's wWeekly, 9 October

1858.

(U.S. National Archives, Washington, D.C.)

|

In April the Company concluded the loft saleshop was too small and

inconvenient for a large-scale business and decided to relocate the

retail operation on the ground floor of the residence to the left of the

Big House. The new shop, fitted up during May, was divided into a store

area and a baling room for packing servants' orders and other

purposes.25 But the salesroom was never used,26

probably because the extension of navigation to Forts Hope and Yale

diverted much of the expected business from Langley.

Hudson's Bay Company vessels (principally the Otter), which by

law provided the only steamship accommodation on the Fraser, were too

heavy to ascend the river beyond Fort Langley. To reduce the expense of

batteaux transport the Company contemplated buying a small river steamer

of 100 tons to ply between Fort Langley and the rapids on the Fraser

River.27 The purchase was not made, however, before the need

was met through an other avenue. In June the Hudson's Bay Company agreed

to license steamers to run between Victoria and the rapids on certain

conditions, among them the carriage of only Company goods and the

payment of two-dollar fee to the Company for every

passenger.28 On Sunday 7 June the American steamer

Surprise made the first steam trip to Fort Hope and a month later

the stern-wheeler Umatilla reached Yale.29 Although

Fort Langley now shared a greater amount of business with the up-river

posts, for two months it continued to be the hub of commercial activity

on the Fraser. During June and July the influx of adventurers reached

its peak with 1,732 persons arriving in a single day in

July.30 Not all of these could afford passage on the river

steamers and they paddled their own craft to the Fraser, calling first

at Fort Langley. Visiting the site in July, Douglas reported sales

averaging $1,500 a day.31 A small tent village was growing

outside the palisade and one enterprising individual opened a log cabin

called the "Miner's Home," offering fare that "would have done no

discredit to a first-class restaurant."32

The arrival of the brigade train on 30 June was a festive occasion

for both Company men and miners at Langley. A Prince Edward Island

prospector, who attended the welcoming ball for the annual visitors,

wrote his impressions of the event for the people back home.

I ... was not a little surprised at seeing the company composed of so

heterogeneous a kind. There were the English, Scotch, French and

Kanackas present, and their offspring, and all so thoroughly mixed with

the native Indian blood, that it would take a well versed Zoologist to

decide what class of people they were, and what relations they had to

each other; though that will cause you but little surprise, when you are

informed that almost all the Co.'s wives are the native Squaws, their

children, which are called half breeds, as a general thing, being quite

fair, docile and intelligent. The Ball was conducted with the best

possible decorum. The music was sweet, from the violin, and the dancing

was performed in the most gracefull manner, by the Indians and the half

breeds, who took a very prominent part on that

occasion.33

Gold fever created a state of intense excitement among the men of the

brigade contingent that summer. Many of them had no doubt personally

talked with miners at Lytton, Fort Hope and Langley. They were not

disposed to continue in the service at £20 a year for middlemen

and £25 a year for "Boates" while others made as much in one week

digging gold. Only after ardent persuasion by Douglas did they agree to

be rehired at an advance of £10 each on their former rate of

pay.34 On 18 July the brigades from Thompson River and New

Caledonia left Fort Langley for the last time. The opening of steam

transportation 80 miles beyond Fort Langley had created a new head of

navigation and meant that henceforth the depot for the Company brigades

would be Fort Hope.35

Inevitably the gold rush caused greater disruption and change in the

fur trade. The sudden influx of thousands of foreigners into a large

unorganized territory immediately raised problems of law, order and

nationality. In his efforts to preserve discipline over the mining

community, Douglas made little distinction between Company and British

interests. Payment of suffrances and the observance of other Company

rules might also be interpreted as a recognition of the authority of the

crown from which the Company received its rights. Revenue officials and

officers of the warship Satellite equally enforced British

customs laws and the Company monopoly. Douglas, governor of Vancouver

Island and chief manager of the Hudson's Bay Company on the Pacific

Coast, personally epitomized the identity of crown and

company,36 but it was an identity that could never endure.

Douglas early realized that government by proclamation was an inadequate

means of permanently administering a new population. Implicit in his

resolve to secure maximum benefit for the Company from the rush was a

fatalistic attitude toward the survival of the fur trade. Company

experience in Oregon had proved the incompatibility of the fur trade and

large-scale immigration. By June Douglas was convinced that the growth

in the number of squatters throughout the Fraser valley was "impossible

to arrest" and he therefore recommended the immediate opening of the

country for settlement with due compensation to the Hudson's Bay Company

for relinquishing its licence.37

The imperial government discussed the problem of governing the

mainland during the summer of 1858. There was strong approval of

Douglas's effort to maintain public order and the rights of the crown

but condemnation of his liberal interpretation of Company rights. In a

dispatch dated 16 July 1858, Colonial Secretary E.B. Lytton reminded

Douglas that "the Company is entitled under its existing license, to the

exclusive trade with the Indians and possesses no other right or

privilege whatever." He pointed out that it was therefore contrary to

law and consequently disallowed to exclude importation of goods or to

prevent any persons from trading with any inhabitants except the Indians

— still more to require a licence from the Company for persons

landing in the territory.38 At the same time Douglas was

authorized to take such measures consistent with the rights of British

subjects.39 Her Majesty's government decided to establish a

mainland colony and proposed that Douglas be appointed governor on

condition that he sever all connections with the

Company.40

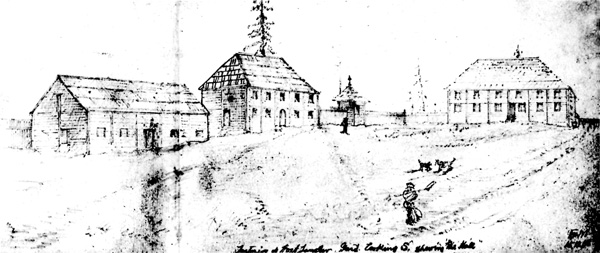

19 The interior of the Fort Langley yard, looking south, showing

"the Hall," by E. Malladaine, 15 December 1858.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

20 Fort Langley, south view, by E. Malladaine, 15 December 1858.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

The Act creating the colony of British Columbia was passed by the

British Parliament on 2 August 1858.41 Douglas was appointed

governor on 2 September42 and by an instrument of the same

date the exclusive trading privileges of the Hudson's Bay Company were

abrogated.43 A detachment of 150 Royal Engineers under the

command of Colonel Richard Moody was immediately dispatched to the coast

to survey land for public sale, lay out the capital, construct roads and

assist in the various duties of colony building.44 The first

two parties, commanded by Captains Parsons and Grant, arrived in

Victoria on 29 October and 8 November respectively.45

Following the arrival of incumbent chief justice Matthew Baillie

Begbie on 15 November,46 a ceremony took place for the

administration of oaths and the formal proclamation of the new

colony.

The official inauguration of the colony of British Columbia took

place at Fort Langley on Friday, 19 November 1858. Although steady rain

throughout the day threatened to mar the event, the ceremony was

conducted with becoming solemnity inside the Big House. An account of

the proceeding appeared in the Victoria Gazette of 25 November.

His Excellency, accompanied by ... a guard of honor commended by

Capt. Grant disembarked on the wet, loamy bank under the Fort, and the

procession proceeded up the steep bank which leads to the palisade.

Arrived there, a salute of 18 guns commenced pealing from the Beaver,

awakening all the echoes of the opposite mountains. In another moment

the flag of Britain was floating, or, to speak the truth, dripping over

the principal entrance. Owing to the unpropitious state of the weather,

the meeting which was intended to have been held in the open air was

convened in the large room at the principal building. About 100 persons

were present.

The ceremonies were commenced by His Excellency addressing Mr.

Begbie, and delivering to him Her Majesty's commission as Judge in the

Colony of British Columbia. Mr. Begbie then took the oath of allegiance,

and the usual oaths on taking office, and then, addressing His

Excellency, took up Her Majesty's Commission appointing the Governor,

and proceeded to read it at length. Mr. Begbie then administered to

Governor Douglas the usual oaths of office, viz.: allegiance,

abjuration, etc. His Excellency being then duly appointed and sworn in,

proceeded to issue the Proclamation of the same date, (19th instant)

viz.: one proclaiming the Act; a second, indemnifying all the officers

of the Government from any irregularities which may have been committed

in the interval before the proclamation of the Act; and a third

proclaiming English Law to be the Law of the Colony. The reading of

these was preceded by His Excellency's Proclamation of the 3d inst.,

setting forth the Revocation by Her Majesty of all the exclusive

privileges of the Hudson Bay Company.

The proceedings then terminated. On leaving the Fort, which His

Excellency did not finally do until today [20 November] another salute

of 17 guns was fired from the battlements, with even a grander effect

than the salute of the previous day.47

As the echoes of the 17-gun salute faded into the mountains, the

impact of the new order was beginning to show in a slowdown of

activities at the fort. Langley, head of transportation and forwarding

centre for the interior, was now superseded by Forts Hope and Yale on

the Fraser and by Port Douglas, the terminus of the navigable portion

of the busy new Harrison-Lillooet route.48 A.G. Dallas, who

replaced Douglas as head of the Company's board of management for the

West Coast, announced in March 1859 that goods would henceforth be

shipped direct to Forts Hope and Yale.49 As a result, most of

the work associated with being brigade depot was abandoned at Langley,

specifically boat building, packing, loading and transportation of

interior outfits, fur baling and shipping, and the lodging, provisioning

and equipping of the brigade contingent. Fewer travellers called at the

fort and business at the saleshop became exceedingly

dull.50

Early in 1859 speculation increased that the site of the original

Fort Langley built by McMillan in 1827 would become the capital of the

new colony. A townsite had been laid out and a public auction of lots

held in Victoria on 25 November 1858 reserved "the best situated lots

... for the special purposes of government."51 But the

favourable combination of shipping, farm and fishery facilities which

had made the south side of the Fraser so vital to the fur trade was not

the criterion used for the final selection of the new capital. Imperial

military strategy ruled out Langley as too vulnerable in the event of an

American attack.52 In February 1859 Colonel Moody designated

a site on the north bank of the river as official port of entry and

capital of British Columbia.53 This decision encouraged the

development of New Westminster54 as the principal commercial

town on the mainland in preference to Fort Langley, the traditional

commercial centre on the Fraser.

21 James Douglas, governor of the colony of British Columbia, 1858-63.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

22 Fort Langley, north view, from the Fraser River, by E. Malladaine, 7

January 1859.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

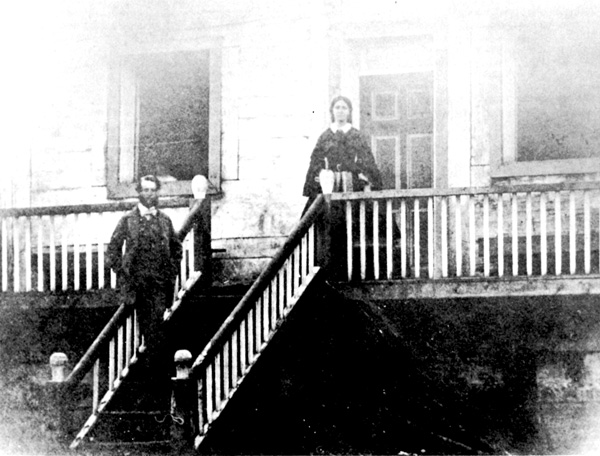

23 William Henry Newton and his wife at the Fort Langley Big House.

Newton was clerk in charge of Langley in 1859-60, 1860-64 and 1874-75.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

|