|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 20

The History of Fort Langley, 1827-96

by Mary K. Cullen

The Coastal Trade

Hudson's Bay Company participation in the Pacific coastal trade was

motivated by nothing less than a desire to eliminate both Russian and

American competition from the Pacific Slope. For many years Russian

trade with Indian middlemen had steadily eaten away at the Hudson's Bay

Company's northern interior trade. The Anglo-Russian Convention of 28

February 1825 provided scope for continental expansion of the British

fur trade, confining the Russians to the Alexander Archipelago and a

narrow strip of the mainland from 54° 40 north latitude along the

coastal range to the 141st meridian and by that degree to the Arctic

Ocean. An additional clause in the convention provided an open

invitation to undercut the Russian coastal trade by conceding to British

subjects the permanent right of free navigation of rivers flowing

through its coastal strip and free trade on the coast for ten

years.1 Company coastal expansion in the next decade aimed to

utilize this invitation although it was against the American coasters

who posed the most immediate threat to the British fur trade that the

Hudson's Bay Company directed the first thrust of its maritime

effort.

The American sea captains with whom the Hudson's Bay Company had to

contend were primarily engaged in trading land furs with coastal Indians

who traded with the natives of the interior. Unlike their Russian and

British rivals, the Americans represented no one company and operated

solely from ships. Their capital was limited and only an elaborate

commercial cycle dependent on commerce in supplies enabled them to stay

in business. The cycle usually commenced in the fall when coasters from

New England and New York were outfitted for a three-year cruise.

Rounding the Horn in December, they called at the Hawaiian Islands, took

on fresh provisions and left behind what was not required for the trade

of the first season. They arrived on the Northwest Coast in March,

traded furs at various locations and usually visited the Russian

American Company's establishment at Norfolk Sound where they exchanged

provisions for sea otter pelts. In September they either cruised

southward to the Spanish settlements to pick up additional supplies and

sometimes a cargo of timber or salmon, or returned directly to the

Hawaiian Islands. Winter was spent in the islands or on a voyage to

Canton to sell the furs. The process was repeated a second year and the

third the coaster proceeded to China and thence to the eastern sea-board

of the United States laden with Chinese produce.2

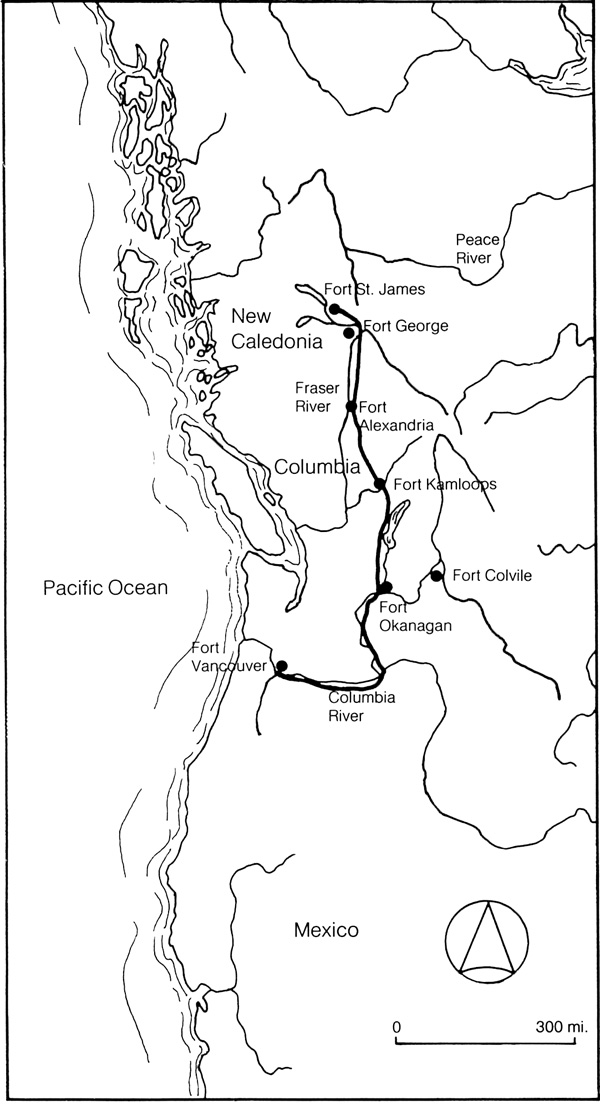

7 The Hudson's Bay Company brigade route to the

interior, 1824.

(Map by S. Epps.)

|

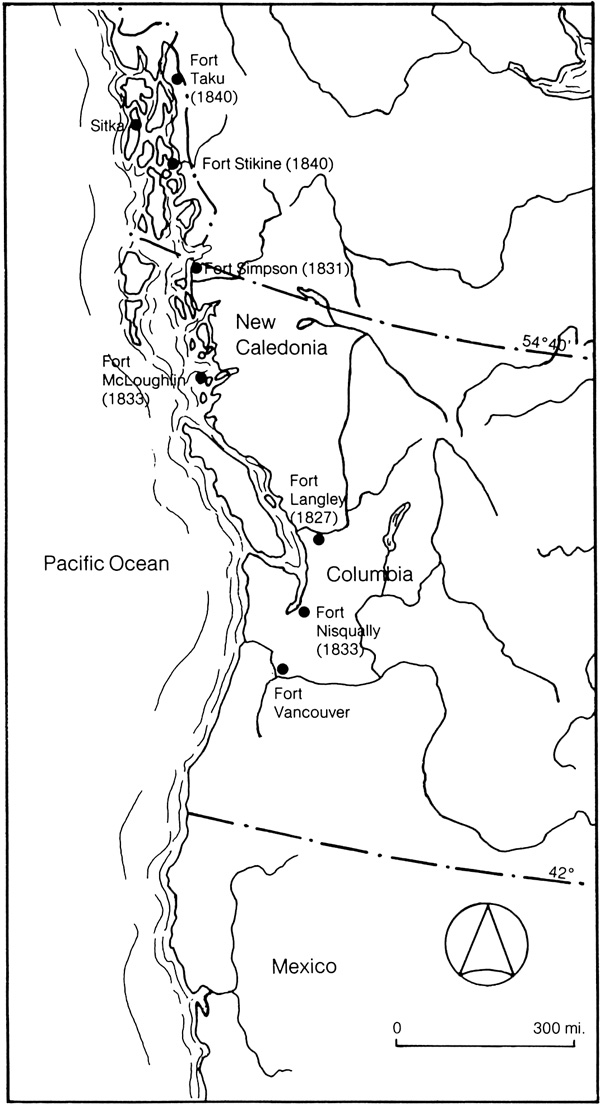

8 Archibald McDonald, officer in charge of

Fort Langley, 1828-33.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

The Hudson's Bay Company coastal strategy discussed at Fort Vancouver

in 1828 aimed to exploit two principal weaknesses in this system; (1)

dependence on sales to China and Russia, and (2) lack of capital. The

London committee ultimately rejected Simpson's 1824 recommendation to

sell furs in China for, like the Nor'Westers, they had to deal through

the agency of the East India Company and their China experience proved

to be just as unprofitable. Fortunately, by 1828 the Chinese market

posed less of a threat since its price for pelts was

declining.3 Simpson and McLoughlin hoped to destroy the other

American market by effecting an agreement with the Russians to supply

manufactured articles and provisions at prices the Americans could not

afford to match. While negotiations were proceeding on this front, a

combination of Company trading forts and ships would undertake an

intensive campaign to spoil American profits by reducing prices of goods

to the coastal Indians below the American cost of supply.4

Fort Langley, situated near the coast and assigned jurisdiction over

Juan de Fuca Strait and the inland of Vancouver Island, was the first

link in the chain of posts intended to eliminate American

competition.

The limited experience of the Fraser River post in the Pacific fur

trade had already indicated the futility of maintaining a fixed tariff

in the face of American competition. As long as opposition coasters were

in the region, McMillan was forced to trade at American

prices.5 The object of monopolizing the trade required more

drastic reductions in the Company tariff. Even though the price paid on

the coast for skins had reached 50 per cent of the London market value,

"in order to strike at the root of the opposition" the Company proposed

to increase prices another 25 per cent. "The Americans," Simpson glibly

reported, "cannot afford to give such prices and must consequently

withdraw."6

From October 1828, application of the price policy at Fort Langley

was the responsibility of Chief Trader Archibald McDonald. A native of

Glencoe Appin, Scotland, McDonald was now about 43 years old. Before

entering the service of the Hudson's Bay Company in 1820, he had studied

the rudiments of medicine and acted as agent for Lord Selkirk at Red

River. He was sent to Fort George on the Columbia as accountant in

September 1821. In 1826 he assumed charge of the Thompson River District

and undertook explorations of the Thompson and Fraser rivers in the

attempt to find a practicable route to the interior. In the opinion of

Simpson he was a jovial fellow, "full of laugh and small talk" a

complete contrast to the austere McMillan; "the former is all jaw and no

work the latter all work and no jaw."7 Still, McDonald was

considered to be well informed and, being fairly articulate, his jaw ran

to the benefit of the historian. His daily record of the 1828 journey

from York Factory8 was followed up by detailed correspondence

from Fort Langley providing an illuminating account of its struggle to

oust the American coasters.

McDonald was to attempt to buy the furs of the Indians before the

arrival of opposition and to offer prices sufficiently attractive to

dissuade the Indians from retaining their furs for the Americans.

Usually the natives were encouraged to trade at the fort itself, but in

times of greater opposition Company trading parties were dispatched with

supplies throughout the region. Either process presupposed amicable

relations with the Indians on the one hand and an abundance of the right

trading goods on the other. During his four-year tenure at Fort Langley

McDonald was to experience difficulties with both.

Like his predecessor, McDonald found his central problem with the

local Indians was less their threat to the fort than their abiding fear

of the Yulcultas which rendered them almost useless to the fur trade.

With every alarm of the fearful tribe from Vancouver Island, Langley's

neighboring Quantlans moved within the shadow of the fort for

protection. At such times there was "not the appearance of a Beaver" and

McDonald recorded,

I see hunting [furs] themselves is perfectly out of the

question. Their dread of the enemy is incredible — they even

desist from Appearing in the water in any manner at the

risk of Starvation with the Yewkaltas are reported to be near, &

— that is not Seldom.9

McMillan had concluded that some order might be instilled in business

affairs should the fur traders actually defend their neighbours. It was

on this basis that McDonald hoped for a material improvement of returns

in the spring of 1829.

The one and only battle between the whites of Fort Langley and the

West-Coast Indians took place at the mouth of the Fraser on 21 March

1829. Yale, Annance and a party of ten men were returning from the

Cowlitz portage where they had entrusted an Indian runner with a packet

of letters and accounts for Fort Vancouver. As they entered the southern

channel of the Fraser delta, they were met by nine canoes, each with an

average of 25 to 30 men, evidently prepared to stop them. The subsequent

encounter was dramatically described by McDonald:

By this time everything being made snug on board and a resolution

formed to rush thro' with the Flag up and a cheerful song, the Gentlemen

kept their eyes upon them. Finding there was no chance of decoying them

or passing down with safety they instantly put about and stemmed the

current...: no shot was fired until our people were fairly within the

point and right in front of the Canoes.., as they commenced the firing

they began to approach gradually — the Boat now getting out of

slack water had to contend with a brisk current along side of a steep

bank, of which the Savages took immediate advantage, and the very two

Canoes that first reconoitred made for the shore — a battle now

becoming inevitable, the Boat also dropped to shore but from some

neglect amongst themselves all were thrown into an alarming dilemma for

a moment by allowing it to shear out again when but seven men had

landed. These however kept the Indians below at sufficient distance

until the two Gentlemen with the other men hook or by crook got ashore

with the ammunition, and rendered the position taken so formidable to

the blood thirsty villains, that in about 15 minutes the whole brigade

of not an Indian under 240 was completely repulsed, and down the main

branch into the open Gulph.10

The bravery of the Fort Langley men lost nothing in the telling. It

was the kind of tale McDonald relished and to the governor, chief

factors and chief traders he proudly announced that "all the Indians

within the River have come to congratulate us on the wonderful triumph

over the invincible Yewkeltas and are most desirous to become our Allies

when 'tis their turn."11

Ultimately Fort Langley's gloriously won alliances proved only as

economically sound as its prices. In March 1829 the American coasters

Owhyhee and Convoy arrived in Columbia with the announced

intention of making a prolonged stand against the Hudson's Bay Company.

Owned by Josiah Marshall and Dixey Wildes of Boston, these vessels at

once began trading at a lower tariff than that of the

Company.12 Since the Quantlans and Musquams of the Fraser

valley were less inclined to hunt than to act as middlemen for such

Puget Sound tribes as the Klallams, the effect of this American

competition was quickly felt at Fort Langley. McDonald promptly reduced

the old tariff from four and five skins to two, two-and-one-half and

three skins per two-and-one-half-point blanket.13 On one

occasion when a Sinnahome chief from the Cowlitz portage came to trade,

McDonald noted in the Fort Langley journal that their stock of blankets

was greater than he "ever knew before going out of a Fort for the same

quantity of Furs." For 35 beaver and 10 otter he had traded 11 blankets,

a pound of brass collar wire, a pound of fine beads and a number of

smaller presents.14

Competition in prices was parallelled, if not equalled, by

competition in types of goods. Besides the popular stout white

blanket,15 that article in greatest demand at Langley was the

gun. Extended destructive campaigns by the better-armed Yulcultas had

created a desire for guns among the rival coastal tribes. As McDonald

argued, if Fort Langley did not accommodate the Indians, the American

vessels would.16 Thus, though the Company theoretically

admitted the impropriety of giving arms and ammunition in trade and

while it usually kept the price of guns high (20 beaver skins) during

the maritime contest, Indian trading guns were a major trade item for

price reduction at Fort Langley and other coastal establishments.

American rivalry made the delayed appearance of the 1829 outfit a

matter of acute anxiety at the Fraser River post. By June 1829 the

schooner expected in March had still not arrived. The Langley Indians,

hoping to see the vessel at any moment "with a vast quantity of goods,"

were reluctant to part with their furs.17 McDonald managed to

persuade some Quantlans to trade their beaver, but he was not sanguine

that Fort Langley could draw more furs in trade to the south. To

undersell the opposition the sacrifice in trade goods had to be

considerable. On 17 June the chief trader recorded, "force of property

alone will now secure furs in this quarter — an Indian was here a

few days ago with a Blanket which costs them on board the [American]

Vessel but 2 Beaver, & did not appear an inferior one

neither."18

When the schooner Cadboro at length arrived in mid-July, it

was found that instead of increasing the order to meet the opposition,

even the original requisition was incomplete. The cause for the

deficiency and delay was the wreck of the Hudson's Bay Company's annual

supply ship. While entering the Columbia River on 10 March 1829, the

William and Ann ran aground on the south bar, its crew and cargo

totally lost. The Ganymede, which had set out from London in

consort with the William and Ann, arrived safely in early May,

but its cargo was extensively damaged.19 With no reserve of

goods on hand, the two small ships, Vancouver and Cadboro,

and the two forts, Langley and Vancouver, were left almost completely

vulnerable in the face of the American coasters.20

For the remainder of outfit 1829, Fort Langley valiantly covered the

deficiency in trade goods, slightly increasing its fur returns. The

Cadboro had delivered only 50 blankets, but with the help of a few

woollens taken across the Cowlitz portage from the Columbia in the fall

and by keeping up the tariff to two and three skins per blanket, the

post managed to pick up 1,600 beaver.21 "We could not of

course think of underselling our rivals," noted McDonald, "nor indeed

would it have been good policy in us, while we had not the where-withal

to satisfy them to invite here Indians that received a Blanket at home

for a Beaver."22

In November 1829 McDonald spent 12 days at Fort Vancouver conferring

with McLoughlin on the Fort Langley arrangements for the following year.

Two topics predominated in the discussions — the salmon fishery and

the coastal fur trade. While building Fort Langley in 1827 McMillan had

forseen the possibilities of large-scale salmon curing. McDonald traded

and cured over 7,000 salmon in August 1829 and hoped to be assigned

enough coopers to develop salmon packing to 500 barrels yearly. His

enthusiasm for the project was shared by McLoughlin who saw trade in

timber, salmon and other articles as a supplementary source of profit

which would greatly strengthen the hand of the Company against its

competitors. Unfortunately, a shortage of manpower in the Columbia

Department necessitated a reduction of the Langley staff from 15 to 12

and concentrated the full attention of the remaining complement on the

coastal fur trade. Besides sending out trapping and trading parties,

Fort Langley would supplement the personnel and direct the operations of

a vessel.23 A convoy of three ships, the Isabella,

Dryad and Eagle, was soon expected from England; the first

two were to remain for service on the coast. When they arrived, the

schooner Vancouver, now plying near the Columbia River, was to be

attached to Fort Langley for trade about Puget Sound and Juan de Fuca

Strait.24

The wreck of another supply ship, the Isabella, on the bar of

the Columbia in May 1830, almost destroyed the Company's coastal

offensive for a second year. Although the cargo was salvaged, there was

now only one extra vessel for the coast, which made it impossible either

to build a new coastal fort at Nass Harbour or to assign a ship solely

for the use of Fort Langley. Nass was postponed and in July the

Eagle, Cadboro and Vancouver were dispatched on a trading

expedition northward. At the mouth of the Fraser, McDonald had the

Vancouver detached from the squadron to bring the "abundant"

outfit up to Fort Langley and then to make a short trip toward Admiralty

Inlet, New Dungeness and other places for the purposes of trade. The

schooner spent a month in the Puget Sound area with Langley trader

Annance radically underselling Captain Dominus of the Owhyhee.

The proceeds of the voyage amounted to a scant 130 skins at a phenomenal

cost — 30 skins left in credit, 55 given in clothing and gratuities

and 45 in arms. The object, as McDonald noted, was not Company gain.

Dominus had been challenged and his trade rendered that much less

profitable.25

During outfit 1831 the Company was able to make its first vigorous

advance against the American coasters. Fort Simpson, established at Nass

Harbour in May, became the centre of coastal opposition under the

direction of Peter Skene Ogden. Ogden kept as many as three Company

vessels on the heels of the American coastal traders, paying two and

three times more than the opposition. In the course of the year he

traded 3,000 beaver at a total loss of £1,600.26

Further south, word was received that the Owhyhee and

Convoy had retired and Forts Langley and Vancouver were able to

restore their tariff. The price of a blanket was raised to two made

beaver and guns to the old cost of 20 skins.27 The annual

returns of Fort Langley rose from 1,400 and 2,500 beaver, prompting one

Columbia officer to comment, "Archy has been doing wonders at Fort

Langley... and is not a little vain of his feat."28

The pause in competition left McDonald free to devote more time to

salmon curing. Langley post had managed to put up 220 barrels of salmon

in 1830 in casks so bad that practically all the pickle was lost and

nine barrels sent for trial in Monterey found no

purchasers.29 Still, McDonald was encouraged to go on

salting, if only for home consumption. About 300 barrels were produced

in 1831, 100 of which sold at ten dollars a barrel to a Hawaiian Islands

wholesaler for resale in Lima.30 In 1831-32, Duncan

Finlayson reported from Oahu that Columbia River salmon were most

popular in the island market, but the Fraser River fish would probably

command a better price. In August 1832 he forwarded 380 bushels of salt

to McDonald to cure 300 barrels of salmon for exportation.31

While Fort Langley was thus commencing a promising salmon curing

enterprise and earning a sound record in the coastal fur trade,

discussions were taking place on new arrangements for the Pacific trade

which threatened the abandonment of the post. In 1830 and 1831 a fever

epidemic broke out in the lower valley of the Columbia which decimated

the Indian population and laid up many of McLoughlin's men. This

unhealthy state of Fort Vancouver, combined with the difficulties of

the Columbia bar, prompted discussion on the relocation of the Columbia

depot at the 1832 meeting of the council at York Factory. Though the

ultimate decision was left to McLoughlin, Simpson had a definite scheme

in mind. His 1829 travels in the Columbia Department suggested Puget

Sound had many eligible locations for the principal depot, with

excellent harbours, fine timber and, above all, fertile soil where

provisions required for the coastal trade could be raised. An additional

advantage to be gained by removing to Puget Sound, Simpson considered,

was the saving of the expense of Fort Langley since "a large proportion

of the returns of that Establishment are drawn from thence, so that if

we were settled at Puget's Sound the post of Fort Langley might be

abandoned without affecting the trade."32

In accordance with instructions from Simpson, McLoughlin had McDonald

examine the country between Puget Sound and Nisqually River in November

1832, "the first object.., to observe if the Soil is suitable for

cultivation, and the raising of cattle; the next, the convenience the

situation affords for Shipping."33 McDonald's report on the

land and harbours was so favourable that building operations commenced

as soon as March 1833.34 The same month McDonald left Fort

Langley for reposting in the Columbia Department and the Fraser River

fort was left in the charge of Yale.35 McLoughlin reported to

Simpson that Yale and 13 men would continue business until a vessel

could be spared from the coastal trade to remove the property and people

to the new establishment, called Nisqually.36

Some months later, McLoughlin began to waver in his belief that Fort

Nisqually could actually replace Langley. During July the Cadboro

was authorized to transport some part of the Langley property, but final

abandonment of the fort was postponed for an other year. McLoughlin

wrote on 2 July,

The people now at Fort Langley can carry on the Fishery but enough

of Trading Articles must be left at Fort Langley to carry on the Indian

trade till next spring, as we cannot yet say whether we ought to abandon

or not, and when our harvest is in and the Brigade come from the other

side, we will have I hope means to keep it up till next spring and carry

on all our operations.37

McLoughlin's reluctance to abandon Fort Langley was influenced by his

growing conviction of the importance of trading posts to the coastal

trade. Although the superintendent of the Columbia Department had

initially promoted an expansion of shipping, even once suggesting the

use of steamers on the coast,38 he had early concluded that

the trade could be conducted with fewer ships and more posts. In October

1832 he instructed Ogden to select sites for new posts,

an important object — as a land Establishment can be

maintained at much less expense; & the Company is never in want of a

Gentleman to take charge of a Land Establishment, but it is extremely

difficult to find Naval Officers to manage the coasting

Trade.39

Fort McLoughlin was established at Milbanke Sound in 1833 and another

fort was planned for the Stikine River the following year. Four coastal

posts, Langley, Nisqually, McLoughlin and Simpson, McLoughlin factually

demonstrated, could "be kept up at less expense than one

Vessel."40 Further, "as a proof of the influence acquired by

establishing posts," McLoughlin pointed out to the governor and

committee in 1834, "we have only to observe that it required the

protection of a vessel and forty men to erect Fort Langley and at

present a clerk and ten men to do the business of the

place."41

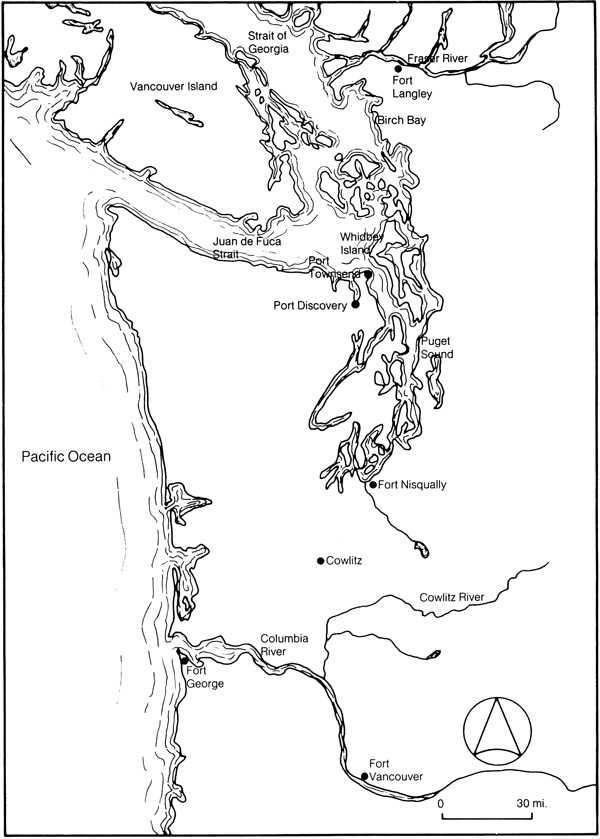

9 Hudson's Bay Company expansion of Pacific forts,

1827-40.

(Map by S. Epps.)

|

Both Simpson and the London committee were in agreement with

McLoughlin on the importance of posts to the coastal trade, but they

also placed an equal value on shipping. Late in 1833 the governor and

committee purchased the Nereide, a large brig of 240 tons, in the

belief that she would prove "well adapted for the Coastal

trade."42 In February 1834 McLoughlin was informed that the

committee had accepted Simpson's recommendation to employ a steam vessel

for navigating the various channels, inlets and rivers on the coast.

Although they anticipated that the steamer might eventually do the work

of four sailing vessels, in the meantime at least five ships would ply

the coast — the Nereide, Dryad or Ganymede, Eagle,

Lama and Cadboro. Efficient use of this heavy complement of

vessels required a more accessible depot than Fort Vancouver. On this

account the committee observed that Fort Vancouver should be maintained

simply as a trading post, farm and depot for the inland establishments

of the Columbia and that the principal depot and headquarters for the

area west of the Rockies should be resituated at the new establishment

on Puget Sound. They contended, like Simpson, that the change of depot

would render it unnecessary to maintain Fort Langley.43

Facilities for agriculture as well as shipping influenced this decision

to relocate the depot at Nisqually. The governor and committee were

anxious to get into large-scale farming and, encouraged by McDonald's

favourable report on Nisqually soil,44 felt a depot there

would provide protection for such an enterprise. When a contrary

assessment of the land was subsequently received from Chief Trader

Francis Heron, Simpson recommended that both Nisqually and Langley be

abandoned in favour of a new site combining the advantages of

agriculture and shipping. In July 1834 he piloted a resolution through

council at York Factory

That a post be established at or in the neighbourhood of Whitby's

Island to be called Fort Langley, which is intended to answer the

purposes of the Posts now occupied in Frazers River and Puget's Sound,

which, on the establishment of that post are to be

abandoned.45

This resolution was followed up by a letter from the governor and

committee to McLoughlin instructing him to appoint "some Person capable

of judging soils" to examine Whidbey Island and the head of Puget

Sound.46

Being manoeuvred into a position requiring the abandonment of Fort

Langley, McLoughlin reasserted his own view of coastal strategy, which

minimized shipping and highlighted posts. Shortly after the

Nereide arrived in the Pacific in April 1834, he returned the

ship as unsuitable for use on the coast.47 He also objected

to the abandonment of Forts Langley and Nisqually on the ground that a

depot at Whidbey Island would lack the proven advantages of fishery and

trade demonstrated by these posts. Writing to Simpson on 3 March 1835 he

pleaded,

there is no place on the coast where Salmon is so abundant or got

so cheap as at Fort Langley; and it we find a sale for Salmon, it would

alone more than pay the expense of keeping up that place: Nisqually is

the best situation for Trade in Puget sound, and though Whitby's Island

is said to be as fine a situation for a Farm as could be desired, yet it

is not conveniently situated for Trade.

Thus he concluded, "I beg to suggest that these two places be allowed

to remain separate until we see how our opponents will act and how the

Salmon sells."48

This argument did not impress the governor and committee, who

immediately censured McLoughlin following the return of the

Nereide to England. They wrote McLoughlin in August 1835,

Your individual opinion with respect to an energetic opposition to

the Americans trading on the Coast, and the means of carrying it into

effect is not in accordance with that of Governor Simpson and the

Northern Council as assented to by us.49

Four months later they followed up this rebuke by a sharp reminder of

the depot question.

We have again to draw your attention to the object of removing

your Principal Depot from the Columbia River to the Coast, say to

Whitby's Island, Puget's Sound, or some other eligible situation, easy

of access, as we consider the danger of crossing the Columbia Bar too

great a risk to be run by the Annual Ships from and to England, with the

Outfits and returns.50

The receipt of this last letter in March 1836 by the two new coastal

ships, the barque Columbia and the steamer Beaver, was

such a dramatic reassertion of London policy that the abandonment of

Fort Langley seemed imminent. McLoughlin, however, stood firm. While he

instructed Chief Factor Duncan Finlayson to examine Port Townsend, Port

Discovery and Whidbey Island, he was determined that the depot question

should not affect the existence of Forts Langley and Nisqually. His

reply of 15 November suggested the existing system was "the most

economical and efficient" for two main reasons. In the first place, the

dangers of the Columbia bar were exaggerated and, since Fort Vancouver

was to be retained as the interior depot, ships would still have to

cross the bar with the supplies and returns of the inland posts.

Secondly, a Whidbey Island depot would be incurring unnecessary expense

because the greater part of the Indians who traded at Nisqually and Fort

Langley could not go there, while the expense of keeping up the

establishment at Fort Langley was in general paid by the salmon trade

which could not be carried on elsewhere.51

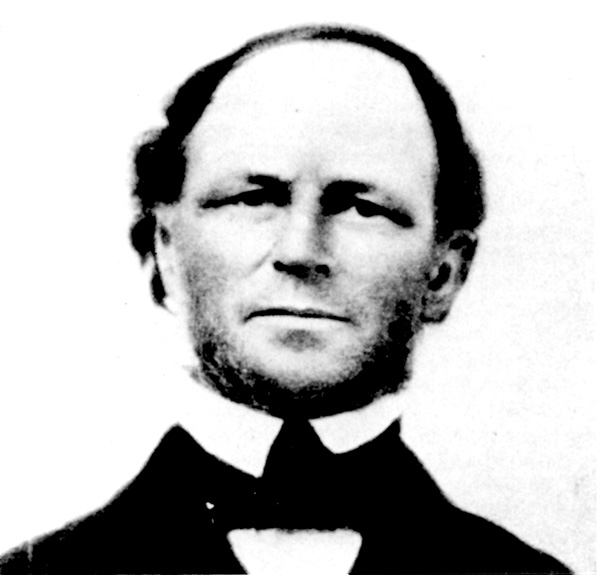

10 The region explored for a new Columbia Department

depot, 1833-38.

(Map by S. Epps.)

|

Finlayson's report on Whidbey Island confirmed McLoughlin's view of

its disadvantages and ultimately convinced London that the existing

arrangement would have to be maintained until a more suitable depot

location could be found.52 The search for a new site was

extended to the southern end of Vancouver Island in the summer of

1837,53 but the idea of relinquishing Fort Langley was no

longer considered. The ongoing need for provisioning the large coastal

establishment of seven vessels and four posts54 accented the

importance of the Fort Langley fishery and farm. Increasingly,

activities at the Fraser River post were orientated to Finlayson's

suggestion "that everything the coast requires in the shape of

provisions not only for the land but for the naval establishments be

supplied and transported by the steamer from Fort Langley and Nusqually

[sic]."55

Yale, who had assumed responsibility for Langley on the eve of its

abandonment four years earlier, would be officer in charge directing

Fort Langley's new role in the fur trade. At the age of 39, Yale had

already served 22 years with the Hudson's Bay Company, 16 years west of

the Rocky Mountains. He had helped in the exploration of the Fraser

River between 1826 and 1828, and as a servant at Fort Langley since 1828

had examined the country around the lower Fraser and Harrison rivers.

Although he was deficient in education, he was known to have "a good

deal of and dress & Management with Indians." Simpson described Yale

as "a sharp active well conducted very little man but full of fire with

the courage of a Lion."56 A strong sense of duty and

persistence through difficulties would characterize his administration

of Fort Langley during the next 22 years.

Salmon curing, cultivation and stock raising had steadily expanded

under Yale's management of Fort Langley since 1833. About 200 barrels of

salmon were cured yearly. The large prairie, seven miles from the fort,

was sown for the first time in 183457 and in 1835 visiting

trader John Work reported 45 acres enclosed there, sown with 80 bushels

of potatoes, 10 bushels of wheat, 45 bushels of peas, 8 bushels of

barley and the same quantity of oats and Indian corn. At the same fort,

30 acres were cultivated with similar crops. Stock consisted of 60 pigs

and 20 head of cattle.58 The first tierces of Langley pork

were received at Fort Vancouver in May 1834.59 This product,

along with spare wheat, peas and salt salmon, helped provision the ships

and supplement the supplies of Forts Nisqually and

Vancouver.60

From 1834 Yale and McLoughlin discussed the idea of relocating Fort

Langley on a site maximizing the benefits of fishery, farm and shipping.

Lulu Island at the mouth of the Fraser and the vicinity of Birch Bay

were both considered but found unsuitable for farming.61

Finlayson examined and proposed a site on the Salmon River in

183662 and McLoughlin accordingly instructed Yale on 16

November 1837 "to move Fort Langley to the place on the Little River as

soon as your business will admit."63 Yale protested that this

situation would have an injurious influence on the salmon and fur

trades. Since the 1837 fishery yielded 350 barrels of salmon besides the

quantity required for fort use, relocation was subsequently postponed

until further orders.64

Fort Langley fur returns steadily declined after 1833. In one sense

this reduction resulted from the success which the Hudson's Bay Company

achieved in the coastal contest. By 1838 the Company had practically

stopped the Americans and extended its trade to "almost every accessible

portion of the Coast as far as the Russian line of demarcation." As one

officer noted, "Owing to this connected occupation, by our Various

establishments, and shipping, we are straitened for room, and we cannot

greatly extend the business of one Post without producing, at some

other, a corresponding depression."65 Yale blamed the low

returns of outfit 1837 on the interference of the steamer Beaver.

The Beaver traded guns and ammunition to the Coquilts of the

Queen Charlotte Islands who, in turn, peddled these articles to the

Indians of Fort Langley, underselling the tariff of the post. To prevent

further decline in returns, trading parties were sent out from Fort

Langley and the sale of ammunition and firearms was suspended in the

vicinity.66 The Company insisted that "Furs constitute the

grand desideration,"67 but it was clear that the survival of

Fort Langley had been predicated on its supply function and that the

coastal trade must become increasingly diversified in character.

By 1838 the Company policy of underselling had successfully broken

the hold which the American trading ships had secured over the coastal

Indians, but it had not placed the Company in its desired monopoly

position. As anticipated, the eradication of competition required entry

into the supply trade which made it profitable for the American vessels

to visit the coast. The importance of foreign commerce as a

supplementary source of profit was recognized by the Company's

establishment of a branch agency in the Hawaiian Islands in

1833.68 Yet exports to the Russian settlements principally

sustained the Americans. From 1828 the Hudson's Bay Company plied the

Russians with offers to supply British manufactured goods and Columbia

provisions such as grain, beef and pork. The Russian American Company

saw the English company as the chief threat to its trade and for nearly

a decade resisted these overtures. At length in 1838 mutual interest in

excluding the Americans and the problem of uncertain supplies prompted

the Russians to consider an agreement.69 With the prospects

of a commercial treaty "more than probable," McLoughlin was summoned to

London to assist in planning the future direction of the Columbia

Department.70

11 James Murray Yale, officer in charge of Fort Langley, 1833-59.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

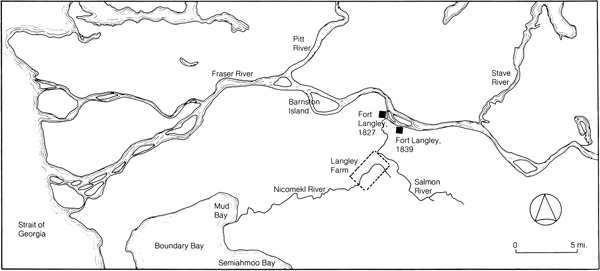

12 Fort Langley, 1839, and Langley Farm. (click on image for a PDF version)

(Map by S. Epps.)

|

When McLoughlin left Fort Vancouver in March 1838, plans were being

made at Langley to increase its fishery and "to pay every attention to

the breeding and rearing of swine" for the production of salt

pork.71 The question of new facilities for these activities

was reopened by James Douglas, the officer appointed to superintend the

Columbia Department in McLoughlin's absence.

Proceeding on the premise that "in a few years Fort Langley will

supply all the salt provisions required for the coast," Douglas wrote to

Yale on 21 November 1838 that the new fort site must be "alike

convenient for the fur and Salmon trade, combined with facilities for

the farm and shipping." Ultimately the fishery was the principal

criterion used for relocation. A prognosis of Langley's future

development was presented in Douglas's conclusion that "the Salmon trade

must not be sacrificed as it will always yield a more valuable return at

less trouble and expense than the farm."72

In the spring of 1839 a new Fort Langley was constructed on the south

side of the Fraser two and one-half miles upstream from the original

post. Removal from the old fort was completed by 25 June73

and the change was reported in a letter from Douglas to the governor and

committee on 14 October 1839 which stated,

We have abandoned the old Langley establishment which was in a

delapidated state, as well as inconvenient in some respects for the

business, and removed all effects, into a new fort built a few miles

higher up on the banks of Fraser's River, the stockades of which, four

block houses, and nearly all the necessary buildings are now erected. It

is fully as convenient for the fur and Salmon trade, as the former site

and, moreover, possesses the important and desireable advantage of being

much nearer the farm.74

New Fort Langley, justified by its fishery and farm, marked a turning

point in the Hudson's Bay Company's Pacific venture, ending the

competitive phase in which the Company created posts strictly for their

value in fur returns. In the new era of monopoly, crop raising and fish

processing were not only seen as support functions of the fur trade, but

also as valid commercial enterprises in their own right. Posts

accessible to shipping were especially valued and soon Fort Langley

wheat, butter, salmon and other products became important elements of a

highly diversified Company commerce extending throughout the Pacific

coast.

|