|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 20

The History of Fort Langley, 1827-96

by Mary K. Cullen

Establishing Inland Communication

After the 1828 extension of British and American joint occupancy of

Oregon, the Hudson's Bay Company continued to use the Columbia-Okanagan

interior supply route from Fort Vancouver. Coastal shipping and other

needs had attracted Simpson and the governor and committee to the idea

of relocating Company headquarters during the 1830s. Yet the absence

of a more effective inland communication, and McLoughlin's argument

that therefore the post would have to be retained as an interior depot

anyway, helped to keep Fort Vancouver in its dominant position. In the

early 1840s, however, powerful political factors were added to

traditional arguments for change with the result that Company

headquarters were moved north. The process began in 1843-44 with

the building of Fort Victoria and the reorganization of Company

management, and was completed in 1849 with the transfer of the

board of management to Fort Victoria and the successful establishment of

a practical brigade route from Fort Langley into the interior.

As early as 1841 Simpson practically abandoned his former hope that

the Columbia River would become the boundary line. Following a personal

visit to the Pacific in 1841, he wrote to the governor and

committee in March 1842 that the coastal boundary would probably

be drawn at Juan de Fuca Strait because "the Government of the United

States will insist on having a post on the North West Coast, and that

Gt. Britain will, for the sake of peace, accept the straits of de Fuca

as a boundary on the Coast." The prospect of this boundary and the

presence of a sizeable American population in the Willamette

valley raised the question of the safety of storing all Company property

at Fort Vancouver. By McLoughlin's own suggestion, the search for a

suitable depot site had been directed to the south end of Vancouver

Island in 1838. Simpson favoured the location for reasons of efficiency

in shipping and he now added political pressures to his decision to

transfer some of the functions of Fort Vancouver to a more northerly

location.1

On 28 June 1842 the council of the Northern Department, assembled at

Norway House, resolved that:

it being considered in many points of view expedient to form a depot

at the Southern end of Vancouver's Island, ... an eligible site for such

a Depot be selected, and that measures be adopted for forming this

Establishment with the least possible delay.2

A year later Douglas built Fort Victoria on a scale large enough to

serve as general depot for the Pacific trade.3

The Company decision to reorganize its management of the Pacific fur

trade was the result of a combination of factors. Relations between

Simpson and McLoughlin had been strained since their disagreement over

the conduct of the coastal trade and during Simpson's 1841 visit to the

coast a serious feud developed between the two concerning the murder of

McLoughlin's son at Fort Stikine. After this event the governor and

committee found that McLoughlin's dispatches were filled with heated

discussions of his son's murder and failed to give adequate accounts of

his district. They were disturbed by the decline in revenue west of the

Rockies and critical of McLoughlin's handling of several specific

matters such as the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company and extension of

credit to American settlers. Reorganization would facilitate the removal

of McLoughlin and anticipate the political division suggested by

Simpson. On 30 November 1844 the governor and committee informed

McLoughlin that his general superintendency would cease on 31 May 1845

and that the Columbia department would be governed by a board of

management of three members and would eventually be divided into two or

more districts. During outfit 1845 the board consisted of Douglas, Ogden

and McLoughlin, but in 1846 McLoughlin went on furlough and after two

more years leave of absence, formally retired from the service on 1 June

1849.4 Although the official division of the Columbia

Department into the Oregon and Western districts was not made until

18535 and Fort Victoria did not become headquarters until

1849, the Company retreat from the Columbia began in 1844.

Scarcely had Fort Victoria been established when events in the

Columbia River valley accented its importance. About 875 American

immigrants arrived in the Willamette valley in the fall of 1843,

reducing the British settlers to a relatively small minority group.

Though a moderate provisional government favourable to everyone was

initially formed, it was uncertain that the more radical American

elements could be held in check. The possibility that the Company's land

might be appropriated or its warehouses looted impressed the governor

and committee, who in the autumn of 1844 ordered the annual supply ship

Vancouver to proceed directly to Fort Victoria instead of the

Columbia. The same year McLoughlin persuaded the Pacific naval commander

to lend support to the British presence by sending HMS Modeste to

visit the Columbia River. By 1845 "Oregon Fever," manifested in a

continuing tide of American immigration and the cry, "Fifty-four forty,

or fight!," brought Great Britain and the United States to the brink of

war. Lieutenants Henry J. Warre and Mervin Vavasour, RE, were sent on a

secret mission in the summer of 1845 to assess British defense of

western North America, but before they completed their task, the two

countries had reached a resolution.6

By the Treaty of Washington signed in June 1846, the 49th parallel

became the boundary between British and United States territory west of

the Rockies. Article 2 left navigation of the Columbia south of the 49th

parallel "free and open to the Hudson's Bay Company and to all British

subjects trading with the same" and stipulated that in the exercise of

that right they should "be treated on the same footing as citizens of

the United States." In practice, however, this guarantee of free and

open navigation proved illusory and Company goods landed at Fort

Vancouver for the interior were subject to import and transit duties

levied by the United States government.7 The building of Fort

Victoria anticipated the disadvantage of having the Company's principal

depot in American territory, but the problem of an all-British

communication with the interior was still unsolved. Early in 1845 the

old idea of Fort Langley as a potential depot for the interior brigades

was revived and in the process of intensive exploration and

experimentation which resulted in a viable route from the Fraser River

to the interior posts, Fort Langley played an active and guiding

role.

Almost a year before the conclusion of the treaty, Simpson wrote to

Yale that in view of the unsettled state of the Columbia, the council

was considering the necessity of finding an alternative route for the

conveyance of the outfits and returns to and from New Caledonia. The

governor asked Yale to communicate any information he might have on a

route from the Fraser and to institute inquiries among the natives on

the practicability of such a route.8 Yale discussed the

matter fully with Douglas in December 1845 and also reported to Simpson

that there was a practicable route "interiorly from the falls on the

south side of the river, by a succession of vallies, small plains, and

lakes, and with only one or two intervening mountains of no considerable

height." He proposed to interview an Indian chief in that quarter to

acquire additional information on the subject.9

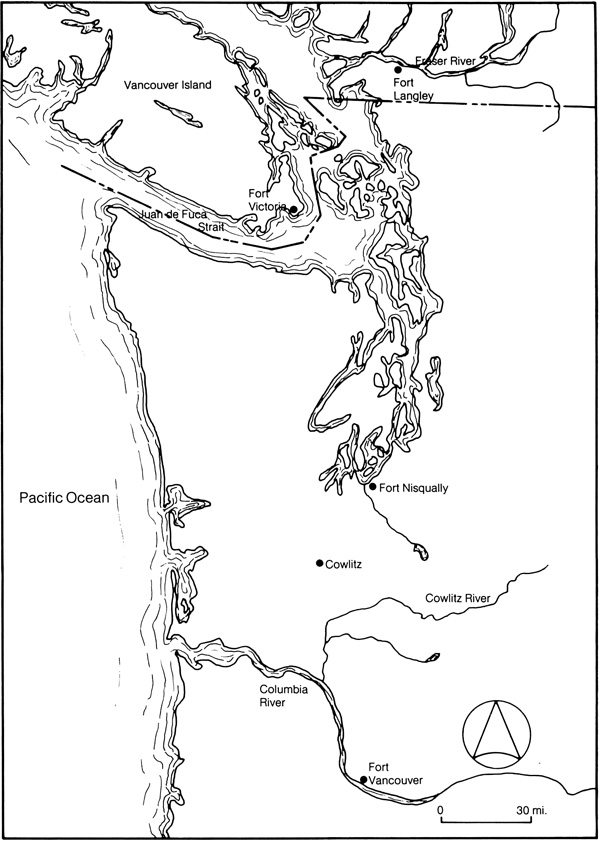

13 The British-American boundary, Treaty of Washington, 1846.

(Map by S. Epps.)

|

Alexander C. Anderson, chief trader in charge of Fort Alexandria who

at this time was also in communication with Simpson on the subject,

volunteered to explore a route to Fort Langley from the

interior.10 The governor accepted Anderson's service and

appointed him to explore two routes in the spring of 1846. Starting from

Fort Kamloops on the Thompson River in May, Anderson followed a route

north of the Fraser by way of a chain of lakes (the Anderson-Seton lake

system) from the Lillooet River to the Harrison which he navigated to

its confluence with the Fraser, taking the Fraser to Fort Langley. A

succession of rapids for nearly 50 miles made the Lillooet exceedingly

dangerous and in seasons of high water impossible for

boats.11 On the recommendation of Anderson the board of

management concluded that the route "will not answer our purpose and

ought never to be attempted."12

On his return journey to Kamloops from Fort Langley in June 1846,

Anderson explored a route by the south side of the Fraser. He ascended

the Fraser 66 miles by water and thence commenced the land journey at

the entrance of Silverhope Creek. When it became apparent that the river

ran in a southerly direction, Anderson retraced his steps and determined

to follow the Coquihalla, a tributary of the Fraser three miles higher.

From the Coquihalla he marched along the valley of the Nicolum over a

small height of land to the Sumallo River, eventually diverging

northward along Snass Creek in a gentle ascent to the highest point of

the mountain pass. Descending on the opposite or northern declivity of

the mountain, his party had to contend with eight to ten feet of snow,

which fortunately was compact enough to support them. A two-day march

from one of the tributaries of the Similkameen brought them into open

country and a camp near Otter Lake where their horses were waiting and

carried them in a two-day ride to the Thompson, the original starting

point. The return journey of 237 miles took 11 days. Anderson's only

objection to the route was the depth and duration of the snow in the

mountains which made the route impassable in early summer, but he

suggested that if the brigades were delayed until the middle of July,

the route should prove a practical communication.13

Although the board of management were at first favourably disposed to

the Coquihalla road, they reserved judgement when Yale informed them

that he had heard of another route which, by following the banks of the

Fraser, avoided the mountains and would therefore be passable at all

seasons.14 They requested Anderson to examine this route in

May 1847 and to report to Yale on its eligibility.15 "The

main point to be born in mind," they wrote to Yale, "is the

accessibility of the route at all seasons as a communication rendered

impassable by snow or water for 6 or 7 months in the year, would be of

little value to us." The latter was "an almost insuperable objection to

the [Coquihalla] road" and induced the board to give preference to a

road which avoided the mountains altogether. They were anxious to

establish a commercial communication with the interior as soon as

possible and while making clear their own preference for the third

route, if feasible, they left final determination of the matter with

Yale and Anderson. Once the matter had been fully discussed at Fort

Langley in the early summer of 1847, Yale was to "proceed in opening the

new road with all the force at his command."16

The report Anderson made of his 1847 journey out to Fort Langley did

not convince Yale that the Fraser valley route was a usable commercial

highway. The party left Kamloops on 19 March and proceeded from there

down the Nicola River to the "Little Forks" near Spences Bridge and

southwest on a rough pathway along the Thompson, Fraser and Anderson

rivers to Kequeloose about six miles from Spuzzum at the head of the

Fraser canyon. The Indian guide Pashallak recommended that near this

point horses could be ferried across the Fraser to a trail which led to

the base of the canyon. Anderson felt the banks and strength of water

precluded a large-scale horse ferry and, determining to test the

navigability of the river, successfully canoed to Fort Langley. Though

the river was then in freshet, Anderson concluded that by portaging at

two or three places the route could be utilized for the conveyance of

goods and furs.17 Yale, who had been involved with Simpson in

his 1828 explorations of the Fraser River, was unconvinced of the placid

quality of the Fraser canyon and had intended that Anderson explore a

section of the riverbank to avoid the difficult part of the Fraser. He

was coming to the conclusion that the route by the Similkameen valley

which Anderson had followed the previous spring would probably be more

feasible, but Anderson felt otherwise and on 1 June left Fort Langley

returning inland by the Fraser to Kequeloose and then overland in a

northwest direction to Kamloops.18 Anderson endorsed the

river route to the board of management, reporting that the rapids, "in

all from 2 to 3 miles," presented "no insurmountable

impediment."19 In July Yale had a party re-explore the 1846

trail and reported that the snow on the mountain ridge was "of

insufficient magnitude to impede the progress of

horses."20

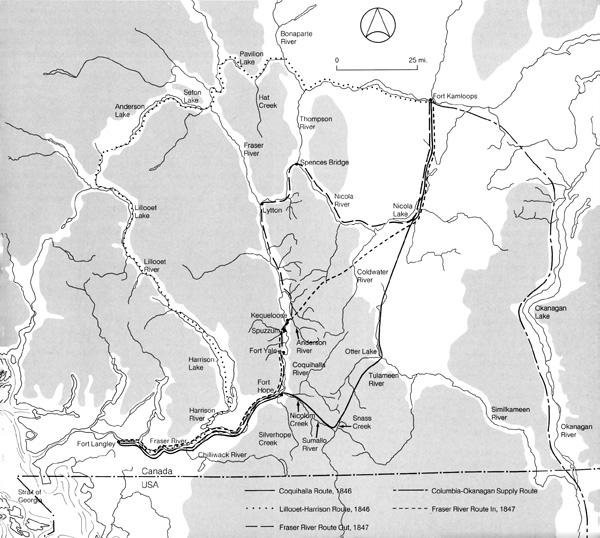

14 Explorations for new brigade routes to the interior, 1846-47. Gray

indicates indicates major mountainous areas.

(Map by K. Gillies.)

|

All of Douglas's hopes sided with the Fraser River route, which he

considered would provide year-round access to the ocean, but in view of

Yale's hesitation he refrained from giving an opinion on the route

"until the 'Falls' have been further examined by good watermen, and

reported practicable; and until we are satisfied that all imminent risk

can be avoided by means of portages or otherwise."21 In

September 1847 Douglas personally retraced Anderson's explorations with

Yale and William Sinclair, spending several days in examining the chain

of rapids known as "the falls." "Before he reached the head of the

falls," Yale wrote privately to Simpson, "he was convinced that Fraser's

River was not quite that placid stream he before seemed to

imagine."22 Contrary to Anderson's picture of two or three

miles of rapids with a few intervening smooth places, rapids extended

from the Saumeena to the upper Teat Village, a distance of 13 miles.

Douglas declared "it is impossible to conceive anything more formidable

or imposing than is to be found in that dangerous defile which cannot

for one moment be thought of as a practicable water communication for

the transport of valuable property." He concluded, however, that

Pashallak's suggestion of crossing the river at Spuzzum was practicable

and that horses could proceed about 13 miles on the north side of the

Fraser to the lower end of the rapids through the narrow winding defile,

soon known as Douglas Portage. From the finish of the road at the lower

end of the rapids to Fort Langley, approximately 130 miles, transport

could be effected by boats.23

During their exploration of the Fraser, Douglas and Yale received

Indian advice of another route to the south of the Fraser which met the

river about 25 miles above Fort Langley. Potentially this route seemed

superior to both the Coquihalla road and the Fraser River route for its

southern position avoided the elevation of the mountain and its

proximity to Fort Langley eliminated the expense of maintaining a fleet

of boats exclusively for river transport. A decision on a new commercial

highway would have to be made soon for already the Company had learned

that its right of "free navigation" of the Columbia was not enforceable

and that goods for New Caledonia which arrived at Fort Vancouver were

subject to duty. Yet the greater efficiency which the latest route

promised recommended its exploration before a final decision was taken.

Aiming for 1849 as the first year for using the new brigade trail, the

board ordered Yale to have this last alternative examined, to come to a

decision and then to start clearing one of the two in the spring of

1848.24 A party from Fort Langley commenced explorations on

26 October 1847, but their report indicated a scarcity of food for

horses, an objection which Yale considered final.25

Early in November, therefore, Yale began making the necessary

arrangements for opening the route by Douglas Portage. On 10 November

his interpreter, Ovid Allard, and a party of six men were sent off to

build a store at the crossing place above the rapids and a house and

store at the foot.26 About three weeks after the Langley men

had begun to build Fort Yale (as the place at the foot of the rapids was

soon called), an incident south of the 49th parallel closed the Columbia

River as a commercial highway. The murder of Dr. Whitman and 13 others

at the mission station at Wai-i-lat-pu touched off the Cayuse Indian War

of 1848 in Oregon and compelled the Company to adopt immediately the

Fraser River route.27 From his letter to Simpson in December

1847, it appears that Yale was aware then that the route to Fort Langley

would be used the next summer.28 In March 1848 the board

wrote to Yale approving his move to establish the route by the Fraser

River and informing him that the Thompson River, New Caledonia and Fort

Colvile brigades could be expected at Langley the first week of

June.29 (In 1825 Simpson had established Fort Colvile as the

centre of the Flathead-Coutonais fur trade.)

The plan of action as outlined by the board in their March 1848

letter forecast the responsibilities of Fort Langley as the key post in

the new transport service. District outfits, with an assortment of goods

and equipment for the officers and men, were immediately forwarded by

the Brig Mary Dare.30 Even before the Columbia

disturbances the Company had sent Samuel Robertson, a boatbuilder, to

Fort Langley to build four large batteaux for future river

transportation.31 Yale was now instructed to send three of

these boats with a supply of provisions for 60 men to Fort Yale by 25

May. The Langley staff was responsible for bringing the men and their

fur returns to the depot and transporting the interior outfits to the

rapids for the return journey. At the fort Henry Newsham Peers, who

accompanied the brigades from the Thompson, was to be placed in the

equipment shop to make up the orders and supply the men. Packs of furs

had to be opened and dusted, and marten and small furs repacked in empty

fur puncheons for shipment to Fort Victoria.32

The magnitude of the work undertaken by Fort Langley as trail blazer

and depot for the brigades was fully acknowledged by James Douglas and

John Work in their letter to the governor and council dated 5 December

1848.

The preparations for opening the new road to the interior for the

passage of the summer Brigade threw much additional work upon the

establishment of Fort Langley, as besides making the road from

Kequeloose to the Ferry, and from thence through the Portage to the

lower end of the Falls of Frasers River, a distance of 18 miles, through

a wooded country, levelling and zig-zagging the steep ascents, bridging

Rivers, there were stores erected for the accomodation of the Brigades

above and below the Falls, boats and scows built for the ferry, and

seven large Boats for the navigation from Fort Langley to the Falls,

there was the heavy transport of provisions to the latter place and a

vast amount of other work connected with that object which it required

no common degree of energy and good management in Chief Trader Yale to

accomplish with 20 men in the course of a severe

winter.33

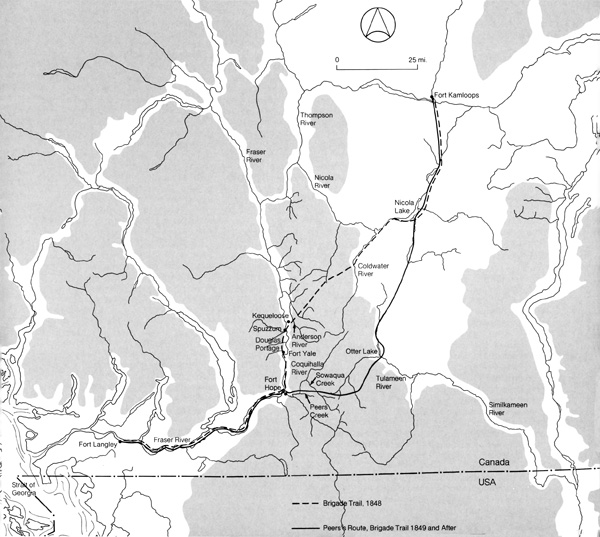

15 Brigade routes to the interior posts, 1848-49. Gray indicates major

mountainous areas.

(Map by K. Gillies)

|

The annual Hudson's Bay Company brigades from the interior made their

first journey by the new all-British route over the Fraser River trail

in the summer of 1848. The three brigades from New Caledonia, Thompson

River and Colvile, numbering 50 men and 400 horses, were dispatched in

the command of Donald Manson and Anderson. A number of the pack horses

were still wild and literally scrambled over the mountains to reach the

Fraser River at Spuzzum. Getting the 400 horses and their lading across

the freshet-swollen river was another strain and it was followed by an

equally difficult journey through Douglas Portage. Meanwhile, the

batteaux from Fort Langley struggled upstream for eight days against the

heavy current, the men towing with lines and pushing with poles to make

the rendezvous at Fort Yale. Only the last 130 miles downstream were

easy, the current swiftly carrying men and baggage to Fort Langley. On

the return trip inland the difficulties were greatly multiplied. The

trade goods were bulky and more perishable than the furs. Large

quantities of merchandise were stolen by the natives who gathered in the

canyon for the annual fishing. Seventy horses were lost during the trip

and by one account 16 and another 25 pieces of

merchandise.34

Both Anderson and Manson heartily condemned the Fraser River route as

a practical business communication with the interior. Although he had

come to agree with the board of management on the unnavigability of the

river above Fort Yale, Anderson was reluctant to endorse the Douglas

Portage as a feasible route for horses. "The portage known as Mr.

Douglas' I do not approve of," he informed Manson in August. "Pasture is

scarce and there is a ravine in it which is too steep and rugged."

Writing Douglas, he added:

My recent experience of the pass in question convinces me that no

portage on a large scale could with prudence be effected there during

the summer months, after the hosts of barbarians amongst whom we have

recently passed are engaged in their fisheries.

Yet the greatest loss of property and horses occurred in the six-mile

mountain tract between the traverse and Kequeloose. Here the horses

stumbled and were maimed and the dislodged packs rolled down into the

river from the precipices.35 Manson considered the road by

Douglas Portage quite usable, but condemned as "utterly impracticable"

the entire route from the Fraser to the plains: "From 45 to 50 miles ...

a succession of very high mountains, rocky and rugged in the extreme,

with deep and thickly wooded ravines dividing each range, and with the

exception of one place, no grass to be found along the whole extent of

the pass."36

Yale attributed many of the difficulties of the 1848 experience to

bad management. The horses used on the way out for carriage in Douglas

Portage were not taken across to the grazing ground or horse guard on

the south side of the river, but left in the portage where there was

little food for them. An extra 200 horses were brought from Kamloops to

the Fraser a month too soon to share in the very scanty means the place

afforded for the 100 there. Each man in the brigade had 15 to 20 horses

to take care of and there were no spare men for a guard to hurry up the

rear. When the last horse was saddled and loaded the day was over and

though the distance was but 30 or 40 miles it was a wonder that they got

through at all.37

In October 1848 Douglas went to Fort Langley to confer with Yale on

alternate arrangements for communication with the interior. As early as

July 1847, Langley's officer in charge had had Anderson's second 1846

route re-explored with the idea that it might be opened with some

changes.38 When Manson reached Thompson River District after

completing his disastrous inland journey of 1848 he had Henry Newsham

Peers re-examine this route.39 The road which Peers

recommended followed successively the valleys of the Coquihalla River

and Peers and Sowaqua creeks, then crossed the dividing ridge into the

Similkameen valley and fell in with Anderson's track of 1846, following

it to the Thompson. His report was favourable enough as to ground, the

ascent of the mountains being gradual on both sides, but he was informed

by his Indian guide that the depth of snow made the mountains impassable

with horses until the beginning of July.40 The same

difficulty had prompted Douglas to reject Anderson's 1846 route in

favour of the one tried via the rapids of the Fraser River. Douglas

still looked on the latter as the least objectionable, but in view of

the "extreme reluctance of Mr. Manson to continue the route of last

summer" he determined to go to the expense of opening a new road "which

in many respects will be found exceedingly

inconvenient."41

Once again responsibility for making the projected interior route

usable fell to Fort Langley. In a memo summarizing their discussions at

Fort Langley in October 1848, Douglas instructed Yale to employ as many

of his own men as could be spared from the duties of his establishment,

with as many Indians as could be induced to assist, to work with Peers

in clearing and levelling the new road. The party would select a

convenient spot near the mouth of the Coquihalla and build an

establishment surrounded with stockades consisting of a dwelling house

and two stores to accommodate the brigades passing and repassing to the

interior. When the interior outfits arrived at Fort Langley in the

spring, Yale would forward them in whole or in part to the establishment

at the Coquihalla, provided they might be left there without

risk.42 After making these arrangements, Douglas later

decided that the outcoming brigades must reuse the summer route of 1848

since it would be

impudent to rely too confidently on the prospect of finding the

new road finished and accessible for the passage of the Brigade in the

spring of 1849, as the depth of snow, the swolen [sic] state of

the rivers, the want of pasture and other causes may and most probably

will disappoint our hopes.43

Besides preparing the new road south of the Fraser, Fort Langley sent

boats and provisions to meet the brigades at the rapids on the Fraser

and provided craft for crossing the property above the

rapids.44

By the early summer of 1849 the Langley party had completed Fort Hope

at the mouth of the Coquihalla and opened the new road to a point where

further progress was impeded by snow. In May Peers and his men went on

the old Fraser River road to repair it and to meet the brigades which

were expected to be near.45 Douglas, who was at the interior

depot to hurry the departure of the brigades, reported to Simpson that

"the Brigade men behaved well at Fort Langley and started in good

spirits in contrast to their behavior the preceding year."46

About six days' batteaux journey from Fort Langley the brigades reached

Fort Hope where they commenced the trip inland by Peers's road. There

were many difficulties, but according to Manson and Anderson the new

route was "infinitely preferable" to the one by the Fraser

River.47 The greatest impediment was the snow in the

mountains which left uncertain the outward passage of the brigade in the

spring. The snow had also prevented the road from being fully cleared,

with the result that Manson and 20 of his men were employed for 15 days

clearing the passage.48 The two-month round trip from Fort

St. James to Langley, however, had caused a late return to Stuart Lake

which was considered highly unfavourable for the distribution of the

outfits.49

There was little doubt that Peers's road was more eligible than the

long circuitous route to Fort Vancouver, but the time involved in the

passage presented some difficulty in a Company timetable designed to get

the inland goods distributed well before the winter. Manson left the

impression that difficulties could be met by more work on the

road,50 but it soon appeared that there was an other reason

for the delay. Yale wrote to Simpson that when Peers and his party went

to meet the brigades

they were found lolling away the time at Kamloops, and to mind the

matter the Langley party who were desired to resume their work on the

new route after their return with the Brigade to Fort Hope, were brought

down here, and thus did Mr. Manson subject himself to the sad necessity

of disencumbering the track of some of its obstructions but which he

might have got performed without any inconvenience some 15 or 20 days

earlier.51

Simpson learned from other sources that Anderson and Manson were at

odds with each other and that their failure to communicate had detained

the New Caledonia brigade several weeks at Fort Kamloops awaiting the

arrival of Anderson with the Colvile returns.52 Douglas

reported that on their return journey they came to high words at Fort

Hope and parted in anger.53

The successful outward trial of Peers's road by the brigades in 1850

finally established the all-British route to the interior. The brigades

crossed the Fraser River ridge without difficulty, the snow being

compact enough to support the loaded horses. The men met with no

molestation from the natives and in general reported favourably on the

road. The Colvile people reached Langley in 17 days' moderate

travelling, and the other brigades took ten days from the

Thompson.54

On 17 August 1850 a rejoicing Douglas wrote to A. Barclay in

London;

It is a great relief to have established the practicability of

this route to the interior through the formidable barrier of mountains

which separates it from Frasers River — while it will have the

effect of imparting a greater degree of confidence of our own

operations, it may also have an important bearing on the future

destinies of the country at large; a triumph, probably the last of the

kind reserved for the Fur Trade.55

For the officer in charge of Fort Langley who had laboured to open

communication at a time when the salmon fishery was increasingly

important, the final establishment of the brigade trail also brought

relief. Yale felt that henceforth the brigades themselves should assume

responsibility for maintaining the route and he confided to Simpson his

hope that "the interesting matter will now be permitted to rest with

themselves, as more consistent with their means, than that which can be

afforded from Langley, and without due consideration might continue to

be required annually forever."56 While Fort Langley's

exploratory work was complete, however, its position as interior depot

involved a host of arduous duties which it undertook for another

decade.

|