|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 20

The History of Fort Langley, 1827-96

by Mary K. Cullen

The Establishment of Fort Langley

Three years after his first visit to the Fraser River, McMillan (now

chief factor) returned to construct the establishment that, it was

hoped, would serve as western headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company.

He was accompanied by François Noël Annance, clerk; Louis Sata

Karata, an Iroquois, and Peeopeeoh, a Hawaiian, all of the former

expedition. With him as well were two other clerks, Donald Manson and

George Barnston, and 19 workmen including carpenters, cooks, blacksmiths

and hunters.1 The party of 25 was transported up the Fraser

by the schooner Cadboro2 and arrived at the site of the

future Fort Langley on 29 July 1827.

The journey from Fort Vancouver took slightly over a month. Leaving

the fort on 27 June, the expedition proceeded in two canoes by way of

the Columbia and Cowlitz rivers to Puget Sound. On 4 July they reached

Port Orchard, the place appointed to meet the schooner. When three days

passed and the vessel had made no appearance, McMillan decided to

continue on toward Admiralty Inlet. There, on 11 July, they met the

Cadboro and embarked on the Fraser.3 Several unsuccessful

attempts were made to enter the river. For a time the vessel was unable

to find a deep channel; then, having found one, it dragged anchor and

drifted out to sea during the night. The following day entrance was

again attempted; the ship grounded but without damage. Finally, after

many delays, the expedition entered the mouth of the river on 22 July,

in 49°5' north latitude.4

Headway up the river was made very slowly and with much deliberation.

Near Lulu Island the vessel passed three Cowitchan villages with

approximately fifteen hundred inhabitants.5 On 24 July the

party saw two trees marked "HBC," a landmark left by the previous

expedition of 1824. The Cadboro reached a point opposite the Pitt River

that evening and anchored later above "Pim island."6 A

"tolerably good situation for a fort"7 existed on the south

side of the river, but McMillan hoped to find a better location and the

vessel continued upstream. Three days later a site was selected some

miles above the Salmon River8 and orders were given to warp

the ship to her destination. Arriving there about noon on 28 July, the

Cadboro found it impossible to get within 300 yards of the shore because

of the "shoalness of the water."9 Since it was necessary to

get the vessel near the fort site, both to cover the operations of the

builders and to facilitate the discharge of cargo, the vessel was

allowed to drift down the Fraser to just below the junction of the

Salmon River.10 Here on 30 July preparations were begun for

erecting the fort which was destined to play a critical role in

extending and consolidating British trade on the Pacific coast.

Admittedly, the motley crew which disembarked from the Cadboro

conveyed scant evidence of such an important mission. In the course of

the month's journey, the total work force of 25 had been reduced by a

quarter, five of the men being incapacitated by severe gonorrhea and

another, Vincent, "suffering dreadfully from Venereal."11 Not

only manpower was crippled; the best of the horses had died on the

passage and the remaining three were so weak when landed that they were

unable to render any substantial assistance.12 McMillan

nevertheless was determined to muster his forces and on 1 August the

remaining 19 men began to clear the ground for Fort

Langley.13

The task was neither rapid nor easy. One of the biggest obstacles to

the small work force was the great density and size of the timber. The

forest on the bank of the river was almost impenetrable, with many of

the trees measuring three fathoms in circumference and upwards of 200

feet high.14 To make matters worse the ground was completely

covered with "thick underwood, interwoven with Brambles and

Briars."15 Fires kindled to consume the cuttings of timber

that had been felled quickly communicated with this surrounding bush. On

one occasion the site was so completely enveloped in flame and clouds of

smoke that "it was with great difficulty that the People succeeded in

getting the Conflagration checked."16

Another source of interference to the building was the various Indian

tribes that passed in continued succession upstream on their annual

migration to the salmon fishery. Curiosity prompted much of the native

population to make a personal investigation of white activity. McMillan

attempted to trade, but more than once pilfering by the natives

compelled him to order everyone off the premises.17 Some fear

was entertained that the Indians actually meant serious harm. Before the

expedition landed, reports circulated that the natives planned to

annihilate the whole party as soon as it came ashore.18 Again

it was believed that some of the fires had been set by the Indians with

the intention of forcing the Company to abandon the

establishment.19

Considering these obstacles, it was with some justification that

McMillan dryly concluded, "the country here is very unfavorable for

hurry in building Forts."20 In a letter to McLoughlin dated

15 September 1827, he summarized the circumstances which continued to

retard progress. He suggested:

Suppose yourself beginning to establish within a mile of Fort

George with a few sickly Canadians, where the wood growsth [sic]

that a Man takes a day to cut down a tree perhaps not to be had

within half a mile of you and then must be sawn before you can get

them [sic] dragged to the place, and to this Indians without

number and you will have some Idea of our

situation.21

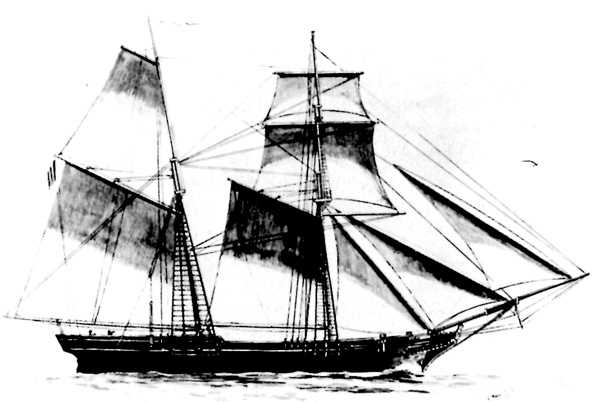

5 The schooner Cadboro, 72 tons, one of the Hudson's Bay

Company's coastal fleet, 1824-61.

(Hudson's Bay Company Archives)

|

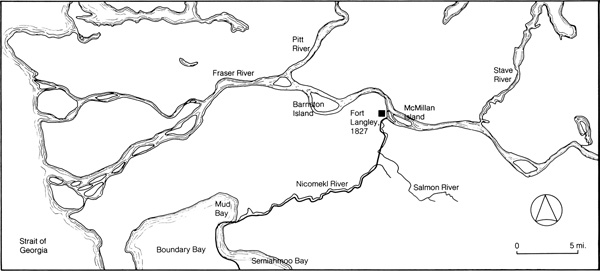

6 Fort Langley, 1827, showing McMillan's 1824 journey.

(click on image for a PDF version)

(Map by S. Epps.)

|

Despite annoyances, Fort Langley steadily took shape. Within a week

of arrival the expedition had prepared materials for a bastion and cut

pickets for the fort walls. On 11 August the bastion was nearly at its

height and two men were sent to raise cedar bark for the

roof.22 So much bark was required that it was soon found

convenient to purchase it from the Indians in trade for buttons, rings

and other articles.23 By Monday, 20 August, most of the

picketing had been cut and hauled to the site and the following day four

men began digging a trench three feet deep for the

palisades.24 A second bastion was finished on 31 August and a

week later, on 8 September 1827, McMillan reported that "the picketing

of the Fort was completed and the Gates hung."25 The

rectangle inside was 40 by 45 yards; the palisade was 4 to 5 inches

thick and 15 feet high. The two bastions, each 12 feet square, were

built of 8-inch logs and had lower and upper floors, the latter being

occupied by artillery.26 The Indians had already begun to

conjecture for what purpose the ports and loopholes were

intended27 and "the Tout Ensemble made a formidable

enough appearance," especially in the eyes of those who had seen nothing

of the kind before.28

With enclosure secure, the fort was sufficiently safe for the Cadboro

to retire. Yet before the vessel could proceed on a trading excursion

north, it was necessary to build a storehouse for the Fort Langley

outfit. The structure was completed on 14 September and immediately

stocked with the provisions, tools and trading goods for the

year.29 On the morning of 18 September, under a salute of

three guns from the newly built bastions, the Cadboro sailed slowly down

the river, leaving McMillan and 14 men to complete living arrangements

and commence business.30

It had taken six weeks to construct a wall of safety, but another

month was to elapse before the post assumed some comfort. The rude bark

shelters which the Company had used as dwellings were now removed to

make room for more permanent quarters.31 The outside shell of

the main dwelling was finished on 22 September and promised to make a

"snug and comfortable" abode. It measured 30 feet long by 15 feet wide

and was divided into two rooms, each provided with a fireplace and two

windows.32 By 19 October the houses for the men were nearly

completed and the garrison was again in the woods squaring timber for

other structures.33 Although building continued throughout

the winter, the completion of Fort Langley was officially recognized on

26 November. That afternoon a flagstaff was erected in the southeast

corner of the fort; "Mr. Annance officiated in baptizing the

establishment and the men were regaled in celebration of the

event."34

Life at Langley was similar in many respects to other Hudson's Bay

Company posts. The men were engaged at a fixed salary on one- or

two-year contracts and were responsible to the officer in charge of the

establishment. Laziness, unruliness and disobedience were not tolerated,

transgressors being promptly flogged or put in irons.35 There

were no white women, but the men took Indian wives, a practice which

reconciled them to wilderness life and also helped foster alliances

favourable to trade. Numerous entries in the Fort Langley journal

indicate that the company took full advantage of this custom. On one

occasion when an Indian arrived with still more women for the

accommodation of the fort, McMillan concluded that this commerce had

begun to supersede the beaver trade and "the whole concern was ordered

off."36

Ample resources for rations enabled the garrison "to live pretty

well."37 A small start of farming was made and in the fall of

1828 the first crop of potatoes yielded 2,010 bushels.38

Sturgeon could be had at times; there were some deer and wild berries

were abundant.39 But the mainstay of the fort was salmon.

During the month of August fresh salmon was supplied by the Indians on

such advantageous terms that McMillan remarked, "had we salt we might

cure any quantity without moving from the Fort, and as reasonable a rate

as the same can be procured anywhere else."40 For winter use

enough dried salmon was bought from the natives "to feed all the people

of Rupert's Land."41

Fort Langley's raison d'être, of course, was the prosecution of

the fur trade. From August 1827 to February 1828 the returns of the

establishment amounted to 938 beaver and 268 otter.42 It was

an unflattering result and while little more might have been expected in

so short a period, there were other fundamental reasons for what

McMillan considered an unsuccessful season.

In the first place, the competition of American traders had created a

climate in which Fort Langley was unable to maintain the uniform

standard of trade.43 Thus McMillan confided to his

superintendent,

In consequence of the Americans having visited the Straits last

Spring we found it impossible to procure Skins in that quarter except at

the same rate at which these people had Carried on their Trade, which

will be a matter for your serious consideration, and a point on which I

would wish to be made acquainted with when I next hear from

you.44

Explaining the situation in greater detail, the chief factor

added,

the Indians about here laugh at us when we ask them five skins for

a Blanket, and first on our arrival they all took their skins back, now

we begin to get a few at the rate of 4-1/2 beaver for a 2-1/2 pt.

Blanket. The Americans sold them 2 yards of fine thick blue duffle for 2

skins which is far finer than our duffle and nearly double the size of

our Blankets, they must have sold a large quantity as all the Indians of

the Gulf are supplied with that article, and should they visit once more

the Sound our Trade is dished for a few years.45

While Fort Langley was thus learning how to win the confidence of the

Pacific Indians and to undermine its American competitors, Simpson was

undertaking his second journey of inspection from Hudson Bay to the

Pacific Coast. He was accompanied by Chief Trader Archibald McDonald,

designated to replace McMillan in charge of Fort Langley, and by Dr.

Richard J. Hamlyn, the incumbent medical officer at Fort

Vancouver.55 Leaving York Factory on 12 July

1828,56 the party took just two months to reach Stuart Lake,

one of the sources of the Fraser River and the site of the district

headquarters of New Caledonia.57 It was Simpson's first visit

to New Caledonia and he was gratified to find that many steps had

already been taken to implement his recommendations of 1824.

Accordingly, for purposes of supply the district was now attached to the

Columbia,

the mode of transport being from Fort Vancouver to Okanagan by

Boats, from Okanagan to Alexandria by Horses, from Alexandria to

Stewarts Lake by North Canoes, and From Stewart's Lake to the outposts

by a variety of conveyances, vizt., large and small canoes, Horses,

Dog Sleds and Men's backs.58

To reduce the costs of this circuitous route the governor still felt

the Fraser River would provide the most efficient transportation and he

therefore determined to ascertain, once and for all, the navigability of

that river. In the course of his journey from New Caledonia to the mouth

of the Fraser he would make the final decision on whether Fort Langley

should become the principal depot of the Pacific Northwest.

The governor's party set out from Stuart Lake on 24 September and,

descending the Fraser about 300 miles, arrived at Fort Alexandria three

days later.59 This part of the navigation was "safe and

tolerably good, the current Strong and abundance of Water, with many

short rapids, but none of them dangerous."60 In order to

examine the possible subsidiary route by means of the Thompson River as

well as the Fraser itself, the party was now divided into two. James

Murray Yale with 14 men and two canoes was to continue along the main

stream to the forks of the Fraser and Thompson rivers; Simpson, with

McDonald, Hamlyn and five men, proceeded across land to Kamloops and

thence along the Thompson to the Fraser.61

The Thompson the governor found "to be exceedingly

dangerous"62 if not impassable. From Kamloops Lake to its

junction with the Fraser, the river was an increasing succession of

violent rapids and dalles.63 Most of these the contingent

managed to shoot, but in one of the last rapids, McDonald recorded, "we

were nearly swamped, for in three swells we were full to the thafts, and

the danger was increased by the unavoidable necessity of running over a

strong whirlpool while the boat was in this unmanageable

state."64 "Indeed," Simpson complained, "there was no comfort

in the whole passage of this turbulent River, as the continual plunging

from one Rapid into another kept us as wet, as if we dragged through

them."65 In this damp state the governor's party reached the

forks on the morning of 8 October where they met Yale and his men

encamped with a large body of Indians awaiting their

arrival.66

Yale's report on the middle part of the Fraser was more encouraging.

He had completed nearly 300 miles from Fort Alexandria travelling

smoothly through a narrow channel and rapid current, and making no more

than three portages totalling less than half a mile.67 This

information was highly satisfactory to Simpson for it meant that nearly

three quarters of the Fraser fully answered his hopes. It now became

necessary to examine the remaining fourth of the river where, it was

apprehended, greater difficulties might be encountered.68

The suspicion was correct for "almost immediately on starting the

character and appearance of the navigation became totally

changed."69 McDonald describes this part of the river in some

detail, but Simpson's journal is probably more vivid. Excitedly the

governor wrote,

The banks now erected themselves, into perpendicular Mountains of

Rock from the Waters edge, the tops enveloped in clouds, and the lower

parts dismal and rugged in the extreme; the descent of the Stream very

rapid, the reaches short, and at the close of many of them, the Rocks...

overhanging the foaming Waters, pent up, to from 20 to 30 yds. wide,

running with immense velocity and momentarily threatening to sweep us to

destruction. In many places, there was no possibility of Landing to

examine the dangers to which we approached, so that we were frequently,

hurried into Rapids before we could ascertain how they ought to be

taken, through which the craft shot like the flight of an Arrow, into

deep whirlpools which seemed to sport in twirling us about, and passing

us from one to another, until their strength became exhausted by the

pressure of the Stream, and leaving their water logged craft in a

sinking state.70

In this manner the greater part of two days was occupied, two days

during which Simpson's cherished idea for transportation on the Pacific

Slope was plainly and unequivocally condemned. Scarcely 100 miles from

the mouth of the river the governor was forced to conclude that "Frazers

River, can no longer be thought of as a practicable communication with

the interior."71 Regretfully he informed the governor and

committee,

it was never wholly passed by water before, and in all probability

never will again.... altho we ran all the Rapids in safety, being

perfectly light, and having three of the most skilful Bowsmen in the

country, whose skill however was of little avail at times, I should

consider the passage down, to be certain Death, in nine attempts out of

Ten. I shall therefore no longer talk of it as a navigable stream, altho

for years past I had flattered myself with the idea, that the loss of

the Columbia would in reality be of very little consequence to the

Honble. Coys, interests on this side of the Continent; but to which I

now, with much concern find, it would be ruinous unless we can fall upon

some other practicable route.72

A frank and disarming admission, Simpson's conclusion was to have a

profound influence on the future course of Pacific development and the

role of Fort Langley in particular.

About 8:00 p.m. on 10 October 1828 the men on watch at the new fort

reported canoes and singing up the Fraser and in a few moments McMillan

and his staff welcomed their governor.73 It was a happy

occasion and the little post was not only anxious but also able to

provide the comfort and repose so hardly earned by the governor and his

fellow travellers. In addition to the main dwelling house, men's

quarters and store which had been completed the previous fall, there

were now two other buildings; one a good dwelling house with an

excellent cellar, a spacious garret and two well-finished chimneys, the

other a low building with two square rooms, a fireplace in each and an

adjoining kitchen made of slab.74 A well-stocked larder

enhanced the snugness of the accommodation. Outside the fort there were

three fields of potatoes with 30 bushels planted in each; inside, the

provision shed exclusive of the table stores was furnished with "three

thousand dried salmon, sixteen tierces salted ditto, thirty six cwt.

flour, two cwt. grease, and thirty bushels salt."75

Simpson was delighted with his reception at Fort Langley and the

respectable footing on which the establishment had been placed in so

short a time. He commended the efforts the post had made to gain the

confidence of the local Indians76 and its virtual

independence of imported provisions.77 Though his journey

down the Fraser had proved that Fort Langley could not serve as the

principal depot, Simpson considered the new fort could fully answer its

second object which was to form an important adjunct of the coasting

trade.78 This role was projected in this dispatch to the

governor and committee, which stated:

I am in hopes this Post will become a valuable acquisition to the

Business, and that in co-operation with the Vessel to be employed in

transporting its outfits and returns, will secure the Trade of the

Straits of St. Jean de Fucca and inland of Vancouvers Island, which has

hitherto fallen into the hands of the Americans.79

|