|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 14

The British Indian Department and the Frontier in North America, 1755-1830

by Robert S. Allen

The End of an Era (1815-30)

I

According to Article 9 of the Treaty of Ghent, the United States

undertook to end hostilities with the tribes and to restore to the

Indians the rights and privileges which they possessed in

1811.1 In compliance with this stipulation, the tribes of the

upper Mississippi valley of the Northwest were invited to send a

deputation of chiefs to a council at Portage des Sioux, a village on the

west bank of the Mississippi River and a convenient central location for

the tribes. The American commissioners headed by William Clark, who was

both governor of Missouri Territory and superintendent of Indian Affairs

for the United States west of the Mississippi River, had difficulty in

persuading some of the native bands to agree to a council. Many chiefs

were bitterly reluctant and the Sauk and Fox were openly defiant.

By July 1815, however, about 2,000 Sioux, Osage, Iowa, Potawatomi,

Shawnee, Delaware and Kickapoo had assembled and established temporary

camps along the river at Portage des Sioux to hear the American offer.

Between July and September a number of treaties were concluded between

the Americans and those Indians present, and on 18 September the happy

commissioners returned in triumph to St. Louis.2

But the Sauk remained aloof and insolent, and boldly declared that

they would never consent to relinquish their traditional lands to the

United States. As a result of the Sauk refusal to negotiate a peace

treaty and based on the recommendation of the commissioners, American

troops invaded Sauk country and built a fort. This action persuaded Black

Hawk to capitulate for the moment and on 13 May 1816 he signed a treaty

which in effect recognized the validity of the 1804 treaty of St.

Louis.3 The Sauk decision induced the remaining bands of

Sioux, Winnebago and Ottawa to negotiate treaties throughout the summer

of 1816; and in March of 1817, the Menominee finally agreed to cede

their lands. The United States was now in complete control of the

Northwest.

Throughout the negotiations between the Americans and the Indians,

Lieutenant Colonel Robert McDouall, based at Michilimackinac and after

18 July 1815 at Drummond Island, received countless bands of Indians

from the Northwest who clamoured for presents and advice at the British

post. William McGillivray, the chief director of the North West Company,

made a final plea to keep Michilimackinac British and thus secure Upper

Canada, the fur trade in American territory and the friendship of the

Indian tribes. Gordon Drummond was prepared to stall and was "disposed

to think as much procrastination should be resorted to as may admit of

your receiving the specific commands of His Majesty's Government on that

Subject."4 But 1815 proved less successful than 1783,

particularly since the Americans were in firm possession of Fort Malden

and southwest Upper Canada. Thus, although the British feared Indian

reprisals such as the Pontiac rebellion, and were angry because

Americans had violated Article 9 of the Treaty of Ghent by moving troops

into Indian territory which they had not held in 1811 frontier security

was theorized to be considerably safer if Fort Malden were returned to

the British. With this foremost in the minds of the British strategists,

Malden and Michilimackinac were quietly exchanged in July of 1815.

For their part the Americans saw every Indian visit to the British

posts as the beginning of a new British plot to encourage the revival of

a tribal confederacy which would fall like a scourge on the defenceless

American frontier back settlements. There was no doubt that a number of

Indian bands had become extremely attached to the British. At a

Drummond Island council in June 1816, for example, a loyal Winnebago chief

addressed an officer of the Indian Department as follows:

I detest the Big Knives [Americans] from the bottom of my

heart, and never took from them a glass of whiskey nor a needle, which

is a convincing proof of my dislike to them. Father, I know of no other

Father but you, and never will be considered or taken for a Bastard,

which would be so if I acknowledged the Big Knives to be my father

also.5

But Lieutenant General Sir John Coape Sherbrooke, the new captain

general and governor-in-chief of British North America, sent explicit

orders to McDouall that the Indians of the Northwest must be told

"distinctly and explicitly" that the British government would neither

assist nor countenance the tribes in any hostility against the United

States.6

The British evacuation of Michilimackinac in 1815 thus destroyed the

last vestige of the British fur trade in the American Northwest. But the

loss was not great since the wealth of the trade had been centred for

some time north and west of Lake Superior in Canadian territory. Also,

Article 3 of Jay's Treaty, which had allowed the free access of British

traders across the border, was argued by the United States to be void as

the result of the Treaty of Ghent. Finally, the Convention of 1818

established the 49th parallel from the Lake-of-the-Woods to the Rocky

Mountains as the international boundary between British North America

and the United States. These three events completed the loss of British

imperial and territorial hegemony in the Old Northwest, and their

control and influence over the tribes of the region. Although Indians

continued to visit the king's posts at Drummond Island and Fort Malden,

these visits had no political significance. Indeed, the new "era of good

feeling" was so confidently and enthusiastically grasped by the British

military that by 1819 the forces for the defence of Upper Canada were

greatly reduced and only small detachments were left to garrison

Kingston, Fort George, Fort Erie, Fort Malden, Penetanguishene and

Drummond Island; and of 173 officers, 80 were absent for the

winter.7

II

The Treaty of Ghent and the American evacuation of Fort Malden on

1 July 1815, however, did not immediately dampen the war spirit which

continued to permeate the atmosphere, particularly in the

Detroit-Amherstburg region. The steadfast loyalty of the Indian tribes

to the British and the friendliness with which visiting chiefs were

received by officers of the Indian Department at Fort Malden aroused

angry jealousy on the part of the Americans. The Indians only

accentuated the mutual and increasing acrimony which characterized

Anglo-American relations in the area at this time. A number of incidents

throughout 1815 and 1816 kept the bitterness temporarily alive.

The refusal of the Americans to yield the little island of Bois

Blanc, which lay very close to the Canadian shore in front of the fort

and village of Amherstburg, to the British following the American

departure from Fort Malden in July was the first of the difficult

problems which plagued relations between the two countries. The British

had occupied the island since 1796 and before; but since regular

navigation travelled along the narrow passage between Bois Blanc and

the Canadian mainland, the Americans claimed that, according to the

Treaty of 1783, the international boundary ran through the middle of the

channel and thus the island was the property of the United States. The

dispute, which threatened to erupt into violence, was eventually

settled only through the intervention of an international commission

which finally awarded the island to Canada.8

The Bois Blanc Island dispute so angered Colonel Reginald James, the

British military commander at Fort Malden, and the civilian population

of Amherstburg and Sandwich that Americans who ventured into Canada,

either socially or on business, became fearful of being "beaten to

death." The feelings of hostility against citizens of the United States

was of such intensity that one American, a Mr. Chittenden who remained

at Fort Malden to guard some public property, was pillaged by order of

Colonel James, who also suggested that if the American resisted his men

should "blow out his brains."9

30 William Claus (1765-1826), deputy superintendent of Indian

affairs, 1800-26.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

The animosity was not restricted to the Canadian side alone. In

September of 1815 Lieutenant Alexander Vidal, a British naval officer, was

arrested by a mob at a public house on the American side of Lake St.

Clair while attempting to recover stolen property and searching for

deserters. Vidal was tried and found guilty of riot; he was fined

$631.10 Less than a month after the unhappy Vidal episode,

the senseless murder of a Kickapoo Indian named Akochis on the Detroit

River by American soldiers further provoked and inflamed the

international feud. The Indian had been hunting squirrels with

some friends on Grosse Island, but was detected by a party of American

soldiers who, apparently fervently committed to defending the

territorial integrity and sovereignty of the United States, chased the

Indian intruders away. In his eagerness one soldier fired at the

retreating canoe and killed the Kickapoo. There was a brief

investigation but no charge was laid.11 The incident was

particularly dangerous and delicate because the Kickapoo Indians had

been visiting their "friends" at Fort Malden, and the Americans were

convinced that efforts were being made to revive the British

protectorship over Indians in the United States.

But the threat to the United States of the rise of a new Indian

confederacy encouraged and supported through the machinations of the

British was non-existent by 1815-16, in spite of the wild imaginings and

accusations of Governor Lewis Cass of Michigan. Although several dozen

bands of Indians continued to visit the British Indian Department

centres each year at Drummond Island and Fort Malden to receive rations

and the traditional presents,12 British policy, official and unofficial,

was strictly and completely opposed to a revival of the Anglo-Indian

alliance.

Governor Cass, however, was annoyed at the influence of the British

Indian Department agents at Fort Malden, and at the large quantities of

presents annually distributed to the Indians who "largely live under the

territorial jurisdiction of the United States." According to Cass the

American frontier was in a constant state of turmoil because the Indians

"assault the Inhabitants, steal their horses, kill their cattle and hogs,

and forcibly enter their houses;" and these Indian depredations,

protested the governor, usually occurred after the natives had visited

the "British agents" at Fort Malden for presents and counselling. Cass

appeared to possess a real fear of the revival of a Tecumseh

Confederacy, "prompted by Indian restlessness and the Zeal of the

British Indian Department." To support his contention, he noted that the

Saukwar chief, Black Hawk, and a large party of Indians were presently

at Malden, and that the greater proportion of Indians east of the

Mississippi River made annual visits to the Canadian side. The governor

speculated that the British agents were keeping the Indians friendly and

loyal in case of future hostilities between the United States and Great

Britain, and that "the Indians are kept in a state of feverish

excitement . . . their minds are embittered and poisoned towards

us."13 Cass concluded by stating that the development of a

humane and sound policy by the government of the United States toward

bringing the Indians within the pale of civilization was rendered

fruitless "by the interference of the British Indian agents." Thus to

avoid the supposed potential spread of death and desolation on the

American frontier, Cass proposed three recommendations; remonstrate

firmly with the British government; prevent the Indians from crossing

the Detroit River into Canada, and use military force, if necessary, to

implement the plan.

III

But the long letter of Lewis Cass in 1819 coincided with the

reduction of British military forces in Upper Canada and a renewed

spirit of Anglo-American cordiality. The Treaty of Ghent, the Rush-Bagot

Agreement, and Convention of 1818 initiated an "era of good feeling" in

which Britain's traditional Indian allies were sacrificed once again as

expendable pawns in the game of international diplomacy. Various chiefs,

and in particular the Sauk chief Black Hawk, faithfully continued to

make the annual trip to the British at Fort Malden, but the days of

Anglo-Indian military alliances had irretrievably vanished. In fact

during the futile "Black Hawk War" in 1832, when the Sauk attempted to

defend their lands against the tide of American westward migration, the

British were conspicuously absent.

Official British Indian policy had developed by the 1820s into a plan

to civilize and Christianize all the Indians residing in Canada and to

establish reserved territories for their exclusive use. The Indian was

no longer viewed as a valuable military ally, and the purpose of

cultivating the tribes as "prospective allies on the battlefield"

against the United States was now considered unnecessary. There were no

more wars for the warriors to fight on behalf of Great Britain, and the

need for continuing the distribution of supplies and gifts to the tribes

through the agency of the Indian Department was being seriously

questioned.14

In 1829 a clear explanation of the new native policy, which was aimed

at diminishing the expenses of the government, was given by Sir John

Colborne, the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada. Colborne suggested

that "civilization" could be extended to the Indians of the province

through "a fund created for their future support by granting leases of

their lands, and selling part of them." This proposal, he contended, was

preferable to the system which had evolved over the years, and which

had "occasioned an enormous expense without conferring any benefit on

the Indians, or insuring their friendship." The lieutenant governor also

proposed that expenses could be saved by fixing the periods of issue of

presents to the Indians at Amherstburg, and that this would minimize the

trouble with the Indians travelling through the United States. But of

vital significance was the suggestion to actively employ the

superintendents "in collecting the Indians in villages, and inducing

them to cultivate their lands, and divide them into lots."15

In conclusion, Colborne urged that education and religious instruction

for the Indian children should be provided, as well as expenses for

medical attention.16

At the same time as Colborne made his recommendations, Sir James

Kempt, the administrator of Lower Canada, after careful research,

also made suggestions for improving the condition of the Indians. Like

Colborne, Kempt urged that the Indians be collected in considerable

numbers and settled in villages where they could cultivate the land.

Kempt also agreed that provision should be made for their religious

improvement, education and instruction in husbandry. To complete the

process of "civilization," the administrator wanted to afford the

Indians assistance in building their houses and in procuring seed and

agricultural implements, and to commute where practicable, a portion of

their presents for this latter purpose.17

The plans put forward by Colborne and Kempt were carefully studied

by Sir George Murray, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies.

Murray concurred with his lieutenants and noted that

the course which had hitherto been taken in dealing with these

people has had reference to the advantages which might be derived from

their friendship in times of war, rather than to any settled purpose of

gradually reclaiming them from a state of barbarism and of introducing

amongst them the industrious and peaceful habits of civilized

life.18

Thus British policy changed at this time from a utilitarian plan of

using Indians as allies to a paternal programme of gradually

incorporating the Indians into white society.19

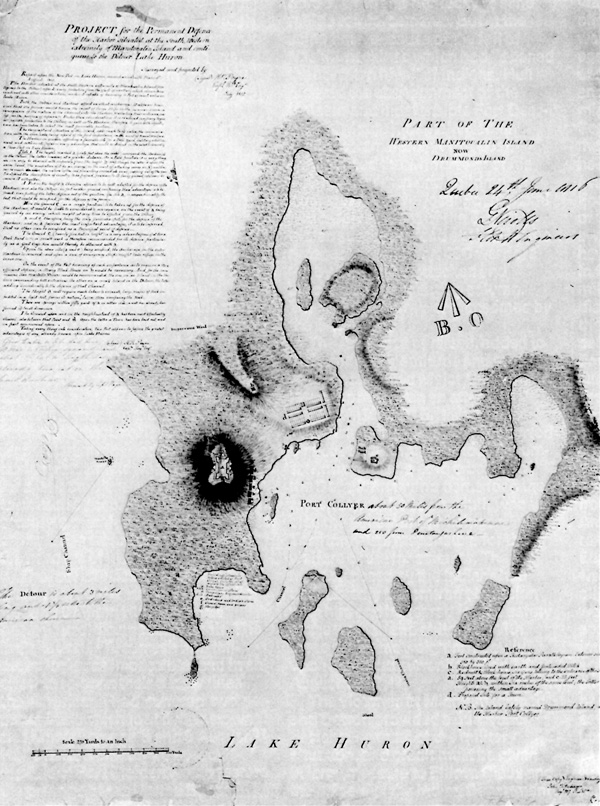

31 British post at Drummond Island, 1815.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

The development of the Indian reserve system in the Canadas was

nurtured following the War of 1812, and reached an initial form of

maturity by 1830. The plan also had origins in Wilberforce, the Clapham

Sect, and the abolition of slavery movement; the Aborigines Protective

Association which protested for better treatment of native peoples

throughout the British empire, and generally a new form of philanthropic

liberalism which was sweeping the British government. In addition,

various influences from the United States, namely the work of the

American Methodists, the development of a factory system for trading with

the Indians, and the popularity of American novels which stressed the

"noble savage" image, had an appreciable effect in determining the new

policy for the Indian peoples of the Canadas.

In the early Leatherstocking Tales, such as The Pioneers

(1823), The Last of the Mohicans (1826), and The Prairie

(1827), for example, James Fenimore Cooper did not characterize the

Indian as did Hugh H. Brackenridge, Indian Atrocities (1782), as

"the Animals Vulgarly called Indians," nor did Cooper refer to the

Indian, as did George Washington in 1783, as a wolf, "both being beasts

of prey tho' they differ in shape." To Cooper the Indian was ennobled,

and marked by the qualities of savage nobility, bravery, cunning,

courage and artfulness in hunting and war.20 Natty Bumpo, the

"beau ideal" of the frontiersman to Cooper, mediated between the

civilized and the savage. Other works such as Charles Mead's

Mississippian Scenery (1819), James Eastburn and Robert Sand's

Yamoyden (1820), the anonymous Land of Powhatan (1821),

Lydia Sigourney's Traits of the Aborigines of America (1822) and

John A. Stone's The Last of the Wampanoags (1829) echoed this new

theme.

The Indian, no longer a threat to eastern civilization in North

America, was now viewed with sentimentality, and the beginnings of a

Hiawathan character began to take root in popular legend. In Traits

of the Aborigines of America, Mrs. Sigourney first contrasts

civilized whites unfavourably with noble savages and then, recalling

frontier warfare and the mutual butchery, pleads for the

Christianization and civilizing of the Indian.

Oh! make these foes

Your friends, your brethren, give them the mild arts

Social and civiliz'd, send them that Book

Which teaches to forgive, implant the faith

That turns the raging vulture to the dove,

And with these deathless bonds secure the peace

And welfare of your babes.21

The poem of Lydia Sigourney clearly showed the degree to which the

attitude toward the Indian had shifted from the days of Brackenridge and

Washington.

For the British Indian Department, 1830 marked the great

transformation. Agents were not merely to secure the loyalty of the

tribes to the king but now were expected to shoulder the "white man's

burden," and carry civilization and Christianity to His Majesty's "Red

children in the forest."22 The proposals of Colborne and

Kempt were approved by Murray and the lords of the Treasury, and after

making the necessary administrative changes the British Indian

Department ceased as a branch of the military and became, as a

Department of Indian Affairs, a branch of the public service.23

With the development of a paternal reserve system, the Indian

Department was confronted with a new and different challenge which was

quite unlike anything experienced during its remarkable 75-year

military history. The old days of courting the allegiance of the Indian

tribes against the Americans and of distributing various gifts, flags

and medals of George III to visiting chiefs at colourful ceremonies

complete with military pomp and formality were now only a glorious

memory.

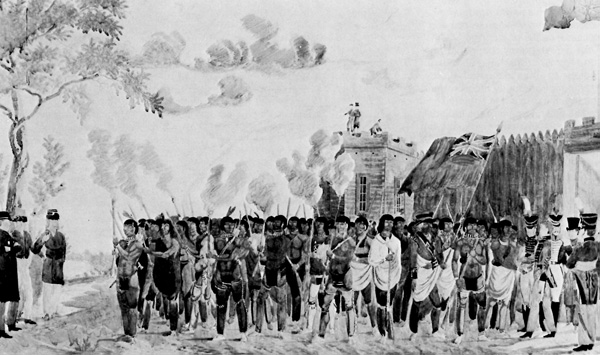

32 Fort McKay (Prairie du Chien), 1815, Indian salute and farewell to the

British. Tradition indicates that the two figures in lower right are Black

Hawk and the British commandant, Andrew Bulger, exchanging farewells. Painting

by Peter Rindisbacher.

(McCord Museum, Montreal.)

|

Since the founding of the Indian Department under Sir William

Johnson in 1755, the service had proven of invaluable assistance to His

Majesty's government in controlling and manipulating the tribes, and

thus in maintaining British territorial hegemony in the wilderness

frontiers of North America. Without the ability and determination of

individual agents such as Butler, McKee, Elliott, Dickson and a host of

others, who encouraged the Indians to support the king, a realignment of

the international boundary between Canada and the United States, to the

detriment of Canada, was a dangerous possibility in 1783, 1794 or 1814.

Throughout the war against the French, but most particularly during the

American Revolution, the struggle for the Ohio valley and the War of

1812, the British Indian Department and the Indian allies won convincing

victories on the frontiers which retarded the advance of American

civilization. This allowed the scattered and sparsely populated

settlements in British North America to achieve a sense of security and

confidence, and prevented their being engulfed by the continual threat

of American republicanism.

33 Uniform of an officer in the Indian Department derived from a

written description of 1823; watercolour by Charles C. Stadden.

|

But 1830 marked the end of an era. Sir William Johnson had died in

1774; John Butler in 1796; Alexander McKee in 1799; Matthew Elliott in

1814; Robert Dickson in 1823; William Claus in 1826, and John Johnson in

1830. These extraordinary men had established a high precedent for

future officers of the Department of Indian Affairs, and their major

characteristics of loyalty, devotion, patience, skill and tireless

energy in the face of often seemingly insurmountable difficulties

provide their finest epitaph.

|