|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 14

The British Indian Department and the Frontier in North America, 1755-1830

by Robert S. Allen

The Indian Department and the Frontier in the American Revolution

(1775-84)

I

The outbreak of hostilities at Lexington in 1775 created a new set

of problems for the British Indian Department. Its role was no longer

one of controlling and appeasing discontented tribes: now the department

was instructed to conduct a planned and careful crusade to win the

allegiance of the Indians to the royal interest. As has been noted,

between 1763 and 1775, the British government attempted to discourage

westward migration, but in the colonies "it was the passion of every

Man to be a Landholder, and the People had a Natural Disposition to rove

in Search of good Lands, however distant."1 The limitless

stretches of unoccupied western territory inhabited by only a few

roving Indians had created an opportunity for quick acquisition of land

by immigrants. With imperial troops concentrated initially along the

eastern seaboard, Americans in considerable numbers pursued their wishes

unhindered by the irritating restraints of British colonial policy.

A summary and explanation of the philosophy of these frontier people

in 1775 was provided by the governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, who had

failed to enforce British regulations.

The established Authority of any government in America, and the

policy of Government at home, are both insufficient to restrain the

Americans; and that they do and will remove as their avidity and

restlessness incite them. They acquire no attachment to Place: But . .

. forever imagine the Lands further off, are Still better than those

upon which they are already Settled, . . Proclamations have been

published from time to time to restrain them, . . . But . . . they do

not conceive that [the British] Government has any right to

forbid their taking possession of a Vast tract of Country, either

uninhabited, or which Serves only as a Shelter to a few Scattered Tribes of

Indians. Nor can they be easily brought to entertain any belief of the

permanent obligation of Treaties made with those People, whom they

consider, as little removed from the brute Creation.2

Thus the American Revolution became in the West, as had other white

confrontations there, an Indian war.

In 1775 both the British and the Americans endeavoured to secure

Indian assistance. In Boston, General Gage urged such a policy; and

Colonel Guy Johnson, nephew and son-in-law of Sir William and the newly

appointed British Indian Department superintendent, perceived that

other colonies were about to follow the example of Massachusetts, and

found that various measures were being taken by "New England

Missionaries and others to alienate the affections of the Indians and

Spirit them up to bad purposes."3 Lord Dartmouth, Secretary

of State for the Colonies, reacted quickly. Writing to Johnson he

advised that

The Time might possibly come when the King, relying upon

the Attachment of his faithful allies, the Six Nations of Indians, might

be under the necessity of Calling upon them for their Aid and Assistance

in the present State of America . . . . His Majesty has received

[intelligence] of the Rebels having excited the Indians to take a

part, and of their having actually engaged a body of them — in Arms

to support their Rebellion, justifies the Resolution His Majesty has

taken of requiring the Assistance of his faithful adherents the Six

Nations.4

6 Colonel Coy Johnson (ca. 1730-88), superintendent general of

Indian affairs, 1775-82. Painting by Benjamin West.

(Andrew W. Mellon

collection, National Gallery of Art. Washington, D.C.)

|

Although both the British and the Americans had begun to recruit

Indian allies, most of the tribes gravitated toward Great Britain rather

than the colonies. The king, as represented by the British Indian

Department, had a history of just dealings with the natives. Gage

astutely observed that "the Indians well know that in all their landed

disputes the crown has a ways been their friend."5 Indeed,

the main duty of the British Indian agent had been to protect the

various tribes from acts of aggression or depredation by the American

settlers.6 Therefore in the autumn of 1775, realizing the

futility of attempting to gain Indian aid, the Americans adopted a

policy of seeking their neutrality. At Fort Pitt a treaty of peace was

negotiated with the Six Nations, Delaware and Shawnee.7 The

commissioners gave assurances that Americans would not settle north of

the Ohio River, and Congress voted its consent. Virginia passed a law

forbidding settlement beyond the river, and for a while the natives

seemed content with the arrangement. But the promises of white

non-expansion were not fulfilled and the British soon gained the active

support of most of the tribes.

The value of the alliance with the Indians was soon appreciated by

the British when, in early September, 1775, an American expedition of

1,000 soldiers landed in a swamp about a mile below the British fort of

Saint-Jean on Lake Champlain. The southwest curtain of the fort was not

completed and the much smaller force under Major Charles Preston could

not have withstood a strong assault. As the Americans pressed through

the woods sensing an easy victory before falling on an ill-prepared

Montreal, about 100 Caughnawaga surprised them and forced them to

retire. The Indian attack not only delayed the American advance on

Saint-Jean but, more importantly on Montreal for over two weeks, a

respite which gave the British time to attend to the defence of the fort

(which eventually fell) as well as the rest of the province. In large

measure, the Indian victory in the woods near Saint-Jean, by delaying

the American advance on Montreal and Quebec, contributed to the complete

defeat of the Americans before the prepared British defences at

Sault-au-Matelot and Près-de-Ville on the last day of

1775.8

7 Daniel Claus (1727-87), superintendent of Indian affairs for

Canada, 1760-75.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

For the British Indian Department, collecting, organizing, feeding

and keeping their native allies in a happy and warlike mood was tedious

and continuous work. At Fort Ontario, Guy Johnson "assembled 1458

Indians and adjusted matters with them in such a manner that they agreed

to defend the communications, and assist His Majesty's troops in their

operations."9 The Indians were to be used principally as

raiders, their favourite targets being the fertile western valleys which

supplied the continental army with grain; thus the tribes were employed in

making "a diversion and exciting an alarm on the frontiers of New York,

Pennsylvania, and Virginia."10 At the three major Indian

Department western posts the tribes rallied to the British standard. At

Niagara John Butler, a veteran of the William Johnson regime, met with

the Six Nation Indians who expressed their satisfaction at having an

opportunity to show their friendship; Lieutenant Governor Henry

Hamilton reported that he could muster 1,000 Indians at Detroit in

three weeks; and at Michilimackinac, Arent De Peyster, soon to be

commandant at Detroit, assured Carleton of the support of the upper

lakes tribes and noted with pleasure that the Sauk and Fox had recently

arrived to declare their loyalty to the British.11

By the summer of 1777, Congress was frustrated in its attempt to draw

the Six Nations to conferences at Fort Pitt and Albany. By refusing the

American overtures the Indians had shown a deep "resolution and

determination to continue firm in their fidelity" to the British

crown.12 Indeed, at the Oswego council, the Iroquois

officially announced their intention of fighting the Americans. Later in

the year during the Fort Stanwix campaign, Indian loyalty was again

tested severely, and their contribution and fighting skills at the

battle of Oriskany enabled the British to check the American relief

force under General Herkimer. Although Mary Jemison, a white woman

living among the Seneca along the Genesee, noted that "our town

exhibited a scene of real sorrow and distress, when our warriors

returned and recounted their misfortunes,"13 the Iroquois

nonetheless were determined to resist the Americans. For the Indians,

the Revolution appeared to be an opportunity to protect their land from

the advance of white settlement.

8 Colonel John Campbell (ca. 1740-1804) replaced Daniel Claus through

political appointment as superintendent of Indian affairs of Canada in

1775, although Claus retained the affection and loyalty of the Indians.

The date of the painting is about 1785.

(Château de Ramesay, Montreal.)

|

The difficult task of the Indian Department in maintaining and

encouraging tribal allegiance to the British was made easier following the

escape of three Loyalist sympathizers from Pittsburgh in the spring of

1778—Alexander McKee, Matthew Elliott and Simon Girty. These three

able and experienced men had lived among the Indians for many years, and

they had considerable influence with the various tribes of the

Northwest. McKee was appointed a captain, and Girty an interpreter,

and although Elliott was initially mistrusted by Henry Hamilton at

Detroit, he, too, soon became a prominent figure in the department. In

later years the direction and decision-making of the Indian Department

was to a large extent shouldered by these individuals but particularly

by McKee and Elliott.

In the summer of 1778, the Iroquois, supported by the newly formed

corps of Butler's Rangers, raided and burned several American frontier

settlements including the prosperous communities of Wyoming Valley and

Cherry Valley in New York. "It is in the highest degree distressing,"

wrote General Washington, "to have our frontier so continually

harrassed by this collection of Banditti under Brant and

Butler."14 But the frontier people of America, "a wild

ungovernable race, little less savage than their tawny neighbours,"

possessed a dogged determination and bitter hatred of the Indian and

refused to be intimidated or pushed out of their

settlements.15 The persistence of these back settlers was to

be rewarded.

Washington authorized a relief expedition to the frontier under Major

General John Sullivan in 1779. The campaign was aimed at the Iroquois

towns along the Finger Lakes. It was hoped that by defeating the Indians

the valuable western grain supplies would be secured for the continental

army. The effort was a success,16 but Sullivan failed to

capture Fort Niagara, the major British supply base in the region. The

Indians and Butler's Rangers had managed to maintain this military

installation, and although the Indian towns and crops were destroyed,

the Iroquois still remained intact as a viable fighting force.

Gratefully, Frederick Haldimand, governor of Quebec, acknowledged that

"the fidelity of these Indians has alone preserved the Upper

Country."17 Native resilience was clearly evidenced during

the following year when, campaigning under Sir John Johnson, they "took

14 rebel officers and 316 men, and destroyed 714 houses and granaries

full of grain, 6 small forts and several mills, which afforded the

rebels the most convenient supplies."18

By 1781, the Indians, weakly supported by the Indian Department and

the British garrisons at the western posts, were firm in their

determination to preserve their territory. "We mean to defend ourselves

to the last man, before we give up our Lands and we will spare none, if

they [Americans] begin with us."19 The military successes of

Joseph Brant over George Rogers Clark along the Ohio River in the autumn

of 1781 gave the Indians a feeling of victory and optimism. But the

continual exchange of atrocities on the frontier fanned the deep-seated

bitterness and contempt.

Persistent raids from the American settlements in Kentucky plagued

the tribes of the Ohio valley. One such raid was to make 1782 the

bloodiest year of the Revolution in the West. In March a contingent

under Colonel David Williamson butchered 90 innocent and pacifistic

Moravian Indians at Gnadenhutten.20 The heartless murder of

these Christian Indians was even more unforgivable because they were

Delaware, and in 1778 Congress had negotiated a treaty of "perpetual

peace and friendship" with them.21 The Indians never forgot

the cold-blooded barbarity of Gnadenhutten and aroused to a fierce

retaliation, the tribesmen hunted Americans and tortured those they

caught with brutal delight.

A second American expedition under Colonel William Crawford crossed

the Ohio River in June and followed Williamson's route. The Indians,

eager for revenge, surprised the American force at Sandusky and routed

it, but not before killing 100: Indian losses were 4.22

Unfortunately Crawford was captured by Delaware warriors under Captain

Pipe, and suffered the worst agonies that the Indian mind could

conceive. Simon Girty witnessed the grisly affair in Pipe's village but

dared not intervene. The news of the death of Crawford prompted the

publication of Hugh H. Brackenridge's Indian Atrocities (1782) in

which the author, by referring to the Indians as "the animals, Vulgarly

Called Indians," exemplified the American attitude toward the Indian

during the American Revolution and the later struggle for the Ohio

valley.23 Haldimand was shocked by the Indian conduct, but

the exasperation of the Indians for the cruelties practised on them by

the rebels in the upper country made the natives lose all

restraint.24

Another Indian victory took place in August at Blue Licks. Two

hundred mounted men from Kentucky, among them such notables as John Todd

and Daniel Boone, were totally defeated by Wyandot and upper lakes

Indians.25

With the American Revolution nearing its completion, the Indians in

1782 had won two successive and decisive battles against the Americans

at Sandusky and Blue Licks. These victories seemingly assured the

preservation of Indian security in the Ohio valley. But in Europe,

Britain was terminating a costly and unpopular war, and the boundary

provisions of the Treaty of Paris gave to the United States this entire

region which the Indians had just successfully defended. The tribes had

no intention of giving up their traditional hunting grounds to their

enemies, the Americans. A new phase in the struggle for possesion of

the Ohio valley was to open.

9 Colonel John Butler (1725-96) held various appointments in the British

Indian Department and commanded the Loyalist corps of Butler's Rangers

during the American Revolution (1777-84).

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

II

The proposals of peace reached Frederick Haldimand, governor of

Quebec, in September 1782. The news caused a general alarm and

discontent among the tribes who feared the loss of their lands and

American retaliation. Throughout the war the Indians were most attached

and serviceable to the royal cause, and suffered greatly "by the

shameful encroachments of the Virginians upon their valuable Hunting

Grounds."26 Prior to 1775, the tribes were settled in ease

and affluence, but only because the British exercised great pains and

bestowed immense capital to effect that settlement. Consequently the

rumour of an Anglo-American peace and possible loss of their lands to

the Americans shocked and angered the natives. Haldimand wrote,

The Indians are Thunderstruck at the appearance of an

Accommodation So far short of their expectations from the Language that

had been held out to them, and Dread the idea of being Forsaken by us,

and becoming a Sacrifice to a Vengeance which has already in many

Instances been raked upon them.27

What was really behind Haldimand's concern was his realization that

if the British wished to secure the safety of the upper Province of

Quebec, the affections of the Indians must be preserved. Therefore, the

governor instructed Sir John Johnson, Superintendent General of Indian

Affairs (1782-1828), to devote a great portion of his time to the

cultivation of "the Private Friendship and confidence of the Chiefs of

greatest note."28 Public councils would be held with the

greatest decorum, formality and military pomp.29 The British

in North America as represented by Governor Haldimand, as early as

February, 1783, had no intention of deserting the tribes because it

would mean (a) the probable restriction of the expansion of

British imperial suzerainty; (b) an added impetus to the westward

rush of American settlers which would certainly result in a flood of

republican tendencies in the sparsely settled upper Province of Quebec

which had had no time, as yet, to establish firm British monarchical

institutions; (c) the loss of the fur trade, and (d) the

destruction of the Indians.

Nevertheless, as a result of the peace negotiations, Haldimand

advised Colonel Arent De Peyster, commandant at Detroit, to inform the

Indians that England would no longer assist them or "approve of their

carrying war into the Enemy's country," but every possible aid would

be given to "secure and defend their own against every Incursion of the

Enemy."30 After the cessation of British offensive

operations, American parties continued to raid across the Ohio River,

and one of these contingents massacred a band of Shawnee at Standing

Stone village. Haldimand insisted, however, that members of the British

Indian Department should discourage the Indians from seeking further

revenge. Policy became a matter of watching for any extension of the

American frontier and trying to assist the Indians in securing the

upper country.31

The first "official news" of the peace treaty—although only a

printed copy of the preliminaries—reached Haldimand on 26 April

1783 via New York. The settlement of the international boundary, by

which England surrendered to the new republic great tracts of land

including the entire Ohio valley, placed the governor in a serious

dilemma. He immediately sent despatches to Brigadier General Allan

Maclean, commandant at Fort Niagara, and to the officers in charge of

the other western posts, giving them the details of the treaty and

advising them to avoid publishing the terms for fear of the Indian

reaction.32

In spite of the endeavours of the British officials at the posts, the

news of the treaty spread rapidly through out the western country and

the Indians by "entire villages" came clamouring to the British seeking

explanations and begging for supplies.33 The state of Indian

feelings was reported in detail by an alarmed but sympathetic Maclean at

Niagara.

The Indians from the surmises they have heard of the Boundaries,

look upon our conduct to them as treacherous and cruel; they told me

they never could believe that our King could pretend to cede to America

what was not his own to give . . . That they were the faithful Allies of

the King of England, but not his subjects . . . they would defend their

own Just Rights or perish in the attempt to the last man, they were but

a handfull of small People, but they would die like men, which they

thought preferable to misery and distress if deprived of their Hunting

Grounds.34

The British garrison commanders did their utmost to prove to their

former allies that England had not forsaken them, and as well pleaded

with the Indians to end further atrocities on the frontier and to

adjust their differences with the Americans. But there was a general

fear that the Indians, embittered by the treaty would retaliate by

attacking the western posts. The horrible memories of the Pontiac

Rebellion just 20 years earlier kept the commanders alert and

cautious.35 Haldimand instructed Sir John Johnson to detain

Joseph Brant at Montreal to prevent him from inciting the Indians to

acts of violence against the Americans and British alike, and to inform

the Indian leader that lands for his Mohawks would be provided in

Canada.36

In a further effort to placate the Indian fear that the British were

abandoning them, Johnson attended a number of councils in the summer of

1783. At Detroit on 28 June, the superintendent told the chiefs that the

terms of the peace which had made them uneasy on account of the boundary

line did not mean to deprive the tribes of an extent of country of

which the right of soil belonged exclusively to them.37 The

difficulty of pacifying the Indians was complicated by the summer peace

mission of Major Ephraim Douglas who was despatched by the Continental

Congress to Detroit and Niagara for the purpose of reconciling the

tribes to the treaty.38 The American party arrived at Detroit

during the Johnson conference, but fearing that the life of Douglas was

threatened and not wishing any outside interference which might alienate

the tribes from their fidelity to the crown, the British refused his

plea to speak to the Indians.39

At Niagara Maclean was incensed at the American for sending messages

and private emissaries among "our Indians."

They are not only our allies. but . . . part of our Family; and

the Americans might as well . . . attempt to seduce our children &

servants from their duty and allegiance, as to convene and assemble all

the Indian Nations, without first communicating their intentions to His

Majesty's representative in Canada . . . if any such person . . . comes

to assemble the Six Nations I shall certainly bring him in here &

keep him till I send for Instructions to General

Haldimand.40

Thus Douglas received the same answer at Niagara and was unable to

assemble the Indians for a council.41 Johnson, however,

distributed several barrels of rum and succeeded in mollifying the irate

Six Nations. His speech to the Indian conference at Niagara sidestepped

the real issues of the boundary line and British military assistance to

the Indians. But, as at Detroit, there was an impression that England

was prepared to guarantee to the Indians the Fort Stanwix line of

1768.42

In August, 1783, Washington directed Major General Baron von Steuben

to arrange with Haldimand the method by which the British wished to give

up the western posts upon the signing of the final peace

treaty.43 Haldimand, however, refused to discuss arrangements

for the evacuation of the posts with Von Steuben or to allow him to make

a tour of the Indian country. His excuse to the American representative

was that he had received no instructions from the British crown. Writing

to Lord North, Secretary of State of the Home Department, Haldimand

expressed his real motives.

The longer the evacuation is delayed, the more time is given to

our fur traders to remove their merchandise, and the greater

opportunity is given to the officers under my command to reconcile the

Indians to a measure for which they entertain the greatest

abhorrence.44

The news of the Treaty of Paris, signed 13 September 1783, placed the

governor in a most precarious position. By the terms of the treaty the

British had totally abandoned their Indian allies. This was a crushing

blow for the preservation of tribal lands in the Ohio

valley.45 Indian resentment was at a high pitch on the

frontier. In spite of the constant efforts of British officers and

Indian agents to establish amicable relations between Americans and

Indians, outrages continued. But on 27 November 1783, Haldimand devised a

binding policy for the frontier which was to continue until the defeat

of the tribes a decade later. The governor explained his policy to Lord

North.

The Indians know that no infringements of the Treaty in 1768 can

be binding upon them without their express concurrence and consent. In

case things should proceed to extremities, the event no doubt will be

the destruction of the Indians, but during the contest not only the

Americans but perhaps many of His Majesty's subjects will be exposed to

great distresses. To prevent such a disastrous event as an Indian war .

. . cannot be prevented so effectually as by allowing the posts in the

upper country to remain as they are for some time . . . the intermediate

country the limits assigned to Canada by the provisional treaty of 1782

and those established northwest of the River Ohio in the year 1768

should be considered entirely as belonging to the

Indians.46

This was the crucial proposal to retain the posts indefinitely and

preserve the Ohio valley as an Indian buffer state, not because of the

fur trade but to maintain British imperial and territorial jurisdiction

in the Northwest to allow the firm establishment of settlement and

British political institutions to develop in the upper province, and to

save human lives.

III

The traditional argument of many American historians is that Britain

continued to hold the posts for the sake of preserving the British

fur-trade monopoly. Yet the Northwest fur trade yielded an annual

revenue of only £200,000. of which two-thirds came from the

American side of the line.47 From the British standpoint, the

financial loss would be minimal as it did not matter whether the furs

were gathered by British or American traders because the pelts would

still find their way to London, the great world marketplace for the

trade. Thus British manufacturers would still profit, and the only

sufferers would be the British traders in Canada. But again, the loss

to the traders in Canada would not be drastic because the larger portion

of the furs gathered in the American territory would pass through

Montreal, which possessed natural advantages over American ports in the

east because of its easy access by lake and river. The total cost of

retaining the posts, by contrast, was estimated at £800,000 per

year.48 From a purely financial or economic standpoint it was

in the interest of Britain to deliver the posts to the Americans as soon

as possible, if the fur trade alone were taken into account; therefore,

one must seek other reasons for Britain's violation of the treaty.

The retention of the posts was owed primarily to a British blunder

and secondarily to an American weakness.49 The blunder was

the utter neglect of the Indians in the peace negotiations with the

United States. Amid the distractions of a falling empire, the British

forgot the Indian completely, one of the most striking oversights in the

whole history of British imperial policy. When news of the proposed

boundary provisions of the treaty reached British North America in

April, 1783, the violent reaction of the merchants, army officers and

especially the Indians caused a reappraisal of western policy in

Whitehall.

Although committed to the treaty, the British devised a new policy

based on two objectives. One was to persuade the Indians that their

interest lay in coming to terms with the Americans. The second

objective was to restore the shattered confidence of the Indians in the

British. Herein lay the dilemma of British policy, since to achieve one

goal was to destroy the other.

The British violation of the treaty passed through several stages.

Originally the retention of the posts was intended to be temporary and

to cover the liquidation of British fur-trading interests south of the

boundary line; then it was to prevent another Pontiac revolt which

would have taken the lives of many British, Americans and Indians; and

finally, a ready excuse was found to postpone the evacuation indefinitely

when, in violation of articles of the treaty, Americans failed to pay

their debts to British creditors and confiscated Loyalist

properties.50

As well, the weakness of the central government of the new republic

was a vital stimulant for the British retention of the western posts.

Working under the Articles of Confederation, the federal government had

neither the financial means nor the authority to stop the migration of

American backwoodsmen or to devise a uniform land and Indian policy. The

backwoodsmen, the natural enemies of the Indian, encroached on Indian

lands and atrocities were exchanged. The British, by retaining the

posts, aided the Loyalists trekking to the upper Province of Quebec,

renewed the allegiance of the Indians, checked American westward

expansion and, contrary to the boundary terms of the Treaty of Paris,

maintained territory in the new republic.

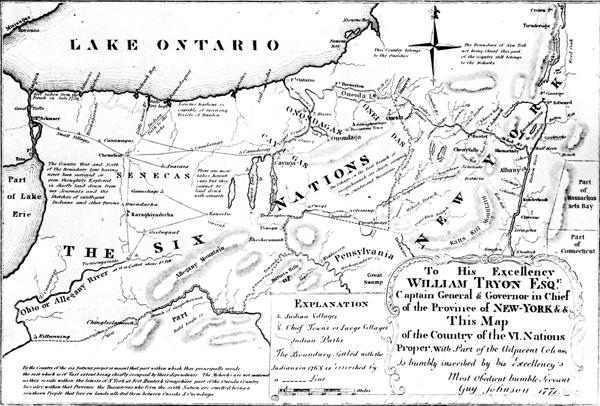

10 Finger lakes district of upper New

York showing the general area of Sullivan's campaign, 1779.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

During the summer and autumn of 1783, the Indians, actively

encouraged and supported by British officials, attempted to form an

Indian confederacy composed of Algonkian tribes and the Iroquois to

oppose the territorial demands of the United States. In September,

delegates from 35 tribes assembled at Sandusky to consider the common

Indian danger and to plan a united defence.51 The leading

Indian spokesman was Joseph Brant, who had distinguished himself as a

Loyalist during the American Revolution. In his speech, Brant proclaimed

the basic Indian right to survive as a people. Thus, he continued, a

satisfactory peace settlement could only be realized by a general

agreement between Congress, represented by all the American states,

and the Indian confederation, represented by all the

tribes.52 Although the need for a confederation was

universally acclaimed, no definite steps were taken at this time.

The British dignitaries present were Sir John Johnson and Alexander

McKee. The latter was not only an officer in the Indian Department but

had family connections with the Shawnee which gave him great influence

among the tribes. It was their task at the conference to soothe Indian

resentment, stave off a general Indian war in which both England and the

United States might become involved, and yet to maintain tribal

allegiance to the British in order to secure an Indian barrier between

the American settlements in the west and the struggling upper Province

of Quebec.

At the council, Sir John delivered his "Tomahawk Speech" in which he

assured the Indians that the peace treaty had in no sense extinguished

their title to the lands northwest of the Ohio River. Johnson reminded

the Indians that by the Proclamation of 1763, all land west of the

mountains had been reserved for them. At the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in

1768, the line had been adjusted with formal Indian consent to make the

Ohio River a permanent eastern boundary for Indian lands. Finally, the

line had been restated at a general conference with American

representatives at Pittsburgh in 1775. Thus the superintendent general

of Indian Affairs told the council that they should put the tomahawk

aside, but to keep it in sight in case the Americans attempted to

molest them.53 Johnson then informed the council that the

British were most concerned with the fate of the Indians, and that the

king would lend at least moral support to the tribes if the Americans in

fringed on their lands.

Johnson's speech achieved a remarkable success with the

tribes.

The meeting with the nations at Sandusky has been of singular

service in removing their uneasiness, and in preventing them from

drawing mischief on themselves by continuing hostilities on the

frontiers of the United States. The Indians' well grounded suspicions of

the designs of the Americans against their country, is confirmed by the

movements of the intending settlers.54

In the spring of the following year, Haldimand received a despatch

from Lord Sydney, Secretary of State of the Home Department between the

years 1783 and 1789, complimenting the governor on his conduct in

retaining the western posts which "will have a good effect on the

Indians."55 Sydney noted that "the interests of the people of

America dictate that they should treat the Indians with kindness, but if

America does not, the tribes may find refuge in His Majesty's

dominions."56 Haldimand quickly accepted the advice of the

secretary of state and in order to repay the Six Nations for their

services in the king's cause, purchased for them a "fertile and happy

retreat" on the Grand River as a substitute for the homelands they had

lost in New York State.57 The governor hoped that "The

Settlement will not only be a frontier to our Settlements in that

quarter, but may be conducive to securing the Furr Trade to this

Province."58

But increasing numbers of American migrants coming to Detroit and

other western settlements through the Indian country kept the tribes in

a state of alarm; "Their Savage Blood is not yet perfectly

Cool."59 Joseph Brant, realizing that a satisfactory peace

could only be attained by a general agreement between the Indian

confederacy and Congress, managed to reassemble the tribes at Niagara

in late August, 1784. The Indian leaders, however, soon became impatient

when the American commissioners with whom they were to treat were

delayed by various preliminaries. Therefore the Algonkian tribes drifted

home to attend to their winter hunting and left the Six Nations waiting

for the congressional representatives.60

By November there were more than 2,000 Indians lounging around the

western posts depending on the British for presents, food and clothing.

Yet it was the firm determination of the tribes to "uphold their rights

which cannot but be approved of by every honest man, and their united

action may secure from the Americans the justice they have a right

to."61 If a rupture was to be averted on the frontier, the

region between the Great Lakes and the Ohio River had to be preserved as

a national home for the Indian. But by the winter of 1784, that dream was

impossible unless Britain was prepared to assist the tribes actively in

their struggle for national survival.

|