|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 14

The British Indian Department and the Frontier in North America, 1755-1830

by Robert S. Allen

The Quiet Years (1796-1807)

I

The signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795 and the evacuation

of the western posts in 1796 had unquestionably reduced the influence

and effectiveness of the British Indian Department among the tribes of

the Northwest. The disgruntled and starving Indians, who had been unable

to hunt or plant corn for the past two years as a result of the military

campaigns, spent the harsh winter of 1795-96 at Swan Creek, on the north

side of the Maumee River near present Toledo, Ohio, and were

provisioned by the Indian Department from the king's stores at Detroit.

Alexander McKee and other officers from the service hoped that in the

spring of 1796 the Indians could be induced to move north into Canada

and settle at Chenail Ecarté, an area 12 miles square just north of Lake

St. Clair.1

The removal of the tribes from the United States was a slow and

disappointing process; however, the British Indian Department wanted the

Indians to be relocated by spring in time for planting and thus reduce

the cost of the enormous consumption of provisions.2 But the

Indians were tardy, and the delays continued until several chiefs

finally offered the excuse that they had planted corn at Swan Creek and

wished to remain at that location in order to harvest the crop. Clearly,

most of the Indians did not want to leave their ancient homelands in

spite of the fact that the political authority for the future of native

survival in the Ohio valley was now vested in the hands of their recent

and hated enemies, the Americans. Instead of the expected exodus of

thousands, only a few hundred Indians eventually migrated to the

supposed sanctuary of British North America. In July some of the

Shawnee under Captain Johnny and Blackbird moved to Bois Blanc Island in

the Detroit River, opposite the grand home of Matthew Elliott. But it

was not until 1797 that scattered bands finally trekked to Chenail

Ecarté.3

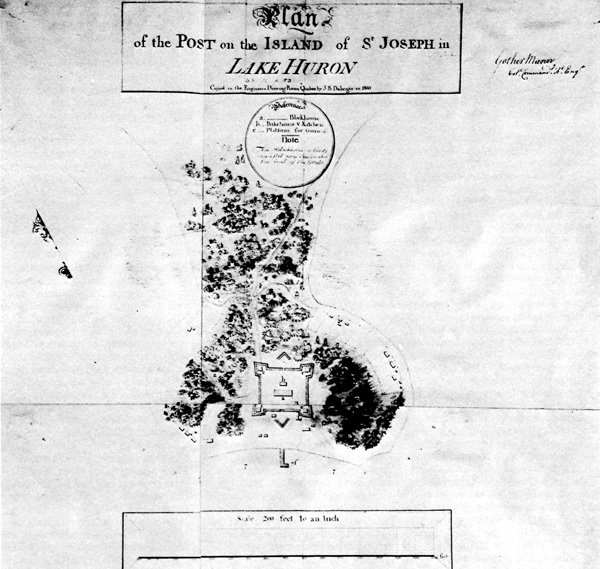

21 The post at St. Joseph, a British

Indian Department centre on the upper lakes, 1800.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

With the American takeover of Niagara, Detroit and Michilimackinac in

the late summer of 1796, the British Indian Department was faced with

the new, if less formidable, task of managing Indian affairs during the

few quiet years of peace. The surrender of the disputed western posts

prompted a reduction of British military forces in Upper Canada, as an

era of Anglo-American friendship was seemingly assured. Only 500 men of

the Queen's Rangers and Royal Canadian Volunteers4 were left

to garrison Kingston, York and the replacement forts that were to be

constructed in Canadian territory: Fort George at Newark on the west

bank of the Niagara River; Fort Malden at Amherstburg on the Detroit

River, and Fort St. Joseph, on the island of the same name at the mouth

of the Saint Marys River.5

The re-location of the military garrisons and the construction of new

posts as well as the termination of the long war with the United States

for control of the Ohio valley necessitated a complete reorganization of

the British Indian Department. At the request of Lord Dorchester,

Alexander McKee devised a "Plan for the Future Government of the Indian

Department" in June, 1796. In his report, the deputy superintendent

general stressed the importance of continuing to employ the officers of

the department to "use the utmost diligence to preserve and promote

friendship between the Troops and the Indians. . .,and to maintain

harmony at the King's [new] posts."6 He also suggested that

in addition to the usual employment of departmental storekeepers, clerks

and interpreters, three superintendents of Indian affairs should be

appointed, one for each of the replacement forts. As a result McKee

recommended his son Thomas as superintendent for St. Joseph, Matthew

Elliott for Fort Malden, and William Claus, a grandson of Sir William

Johnson, for Fort George.7 Just prior to his departure for

England, Lord Dorchester approved the appointments, and the British

Indian Department, thus restructured, assumed its new role of managing

Indian affairs.

In June 1797 at St. Joseph, Alexander McKee and his son Thomas met

with Ottawa and Ojibway to negotiate the purchase of the island which

"the Indians readily agreed to," and to attempt to curb the traditional

intertribal warfare between the Sioux and the Ojibway.8 The

Indians promised to visit and trade at the new British post and

"appear[ed] to be friendly as usual."9 Captain Peter

Drummond, the commandant at St. Joseph, seemed content with the

situation and noted with enthusiasm that the construction of the

barracks and the buildings for the British Indian Department were

progressing smoothly.10 But the attitude of the British

military after Greenville was that the Indians should be abandoned to

their own devices, as there would be no future need for their

assistance. The new object of the government, observed Thomas McKee, was

"to have as few Indians to come to the Posts as possible in order to

lessen the expenditure of Provisions."11

II

The peacetime policy added new complications to the general

administration of the Indian Department in Upper Canada. Since 1775 the

department had faced continuous crises, and as a result great freedom

had been bestowed on the various agents in regard to obtaining

provisions and gifts for the British Indian allies. But for a decade

after 1796, a period of comparative tranquility existed in the

Northwest, and this meant the return to a rigid routine and the strict

accounting of goods. To compound the situation the expenses of the

Indian Department were defrayed from the army budget, and this created a

definite cause for future friction. The old, irritating problem of

military jurisdiction and authority in the affairs of the Indian

Department was to reach a climax in the McLean-Elliott feud at Fort

Malden in 1797.

As early as 1795, the department had been accused of depredations.

Joseph Brant noticed that "Goods intended for the tribes [were] often

not received. . . . The Enormous expense of which much seems to

disappear before getting to the Indian country."12 Lieutenant

Governor Simcoe argued that the apparent unpopularity of the Indian

Department arose "from the changes of peculation and from the belief

that the officers of the Department foment ill will between the Indians

and the United States."13 He further considered the

department as" an Establishment not only incompetent and dangerous as

far as concerns foreign nations, but to be too extensive in its

objects."14

These charges of pillage resulting in personal profit were not mere

speculation or unfounded, particularly in the case of Matthew Elliott.

In the autumn of 1796, traveller Isaac Weld estimated the size of

Elliott's estate at the mouth of the Detroit River as 2,000 acres, a

very large part of which was cleared and "cultivated in a style which

would not be thought meanly of even in England."15 The house,

Weld stated, was the best in the whole district, and situated 200 yards

from the river, the parlor windows afforded an excellent view of the

Indian canoes passing and repassing before Bois Blanc

Island.16 Elliott used his farm as his Indian agency, and

with the assistance of his storekeeper and clerk, George Ironside,

exercised control of Indian affairs in the region. Alexander McKee had

retired to his home on the nearby Thames River, and from there directed

a general supervision of Indian affairs in Upper Canada.

The affluent life-style of Elliott and his customary liberality of

goods toward the Indians, for which the army had to account, soon began

to annoy the military at Malden who had been ordered to economize. In

return the Indian Department was disgusted at the action of the British

officers who had agreed to lend 50 barrels of pork to the Americans at

Detroit in the autumn of 1796 when supplies for the Indians appeared

scarce. The problem of the distribution of supplies to the Indians was

acute now that peace had come to the Northwest. The basis of the

difficulty was that the military held the purse-strings and the Indian

Department the power in regard to the Indians. To ensure that an

accurate account of provisions and gifts could be maintained, the

military decided that their officers should be present on each occasion in

which Indians received goods. But small parties of Indians were

constantly arriving to proclaim their loyalty to the British king and to

receive gifts, as was the tradition. Since Elliott's farm was more than

one mile from the British officer's quarters at Fort Malden, it was

impossible for army representatives to be present at every occasion.

The commandant at Fort Malden (Amherstburg), Captain Hector McLean,

initiated the feud in a letter of complaint to James Green, the military

secretary at Quebec. After discussing the details of the construction of

several buildings at the new post, McLean commented on the expenses of

the enormous consumption of provisions by the Indians, and thought that

the high costs could be checked without the least detriment to the

Indian service.17 McLean had hoped that the presence of

officers during the distribution of goods would curb any excesses by the

Indian Department. But Elliott refused to detain various Indian

dignitaries in order to accommodate the army. This action prompted

McLean to write two long letters to Green, in which the commandant

accused the Indian Department of carelessness and lack of formality.

McLean was astonished at the consumption of provisions and suggested as

a remedy the gradual diminishing of the issue of provisions to the

Indians, and that native visits to the post should be made less

frequently. "I have reason to believe that their coming in so often is

encouraged by Mr. Elliott."18 McLean further objected to the

fact that the government had to pay Elliott £160 per year for

storage, because the Indian stones were kept at his farm and not at the

garrison. In addition, since the farm was over a mile away, the officers

found it inconvenient to attend every delivery of presents, particularly

when such short notice was given and generally at the dinner hour. Also,

the distance, argued McLean "renders the peculation the more easy,

and detection less so."19 Finally, the commandant delivered a

scathing denunciation of Elliott.

He lives . . . in the greatest affluence at an expense of above a

thousand a year. He possesses an extensive farm not far from the

garrison stock'd with about six or seven hundred head of cattle &

. . . employs fifty or sixty persons constantly about his house &

farm, chiefly slaves. . . . How his wealth had been accumulated, . . .

is well known.20

Matthew Elliott, confident of the power of the Indian Department,

appeared unperturbed at these verbal attacks and smugly continued the

feud with McLean by issuing provisions to Indians, often in the absence

of the army officers from Malden. But a week after the explosion

regarding provisions, McLean uncovered another aspect of Elliott's

activities—the supposed peculation of bread. The normal practice in

securing bread for the Indians was to have Elliott send a requisition to

the commanding officer at the fort for a specific amount. With the

signing of the order form, Elliott would despatch his servants to the

garrison bakery to obtain the bread. However, McLean noticed that

Elliott's negro slaves were picking up some 20 to 25 loaves per day.

Apparently Elliott was getting free bread for himself and his large

household staff from the garrison bakery under the pretext of acquiring

it for the Indians. The commandant immediately ordered the commissary

not to charge any bread to the government account unless delivered

directly to the Indians for their own use.21

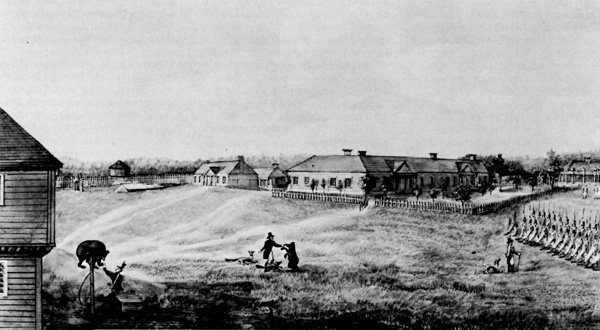

22 Fort George, Niagara River, one of the three

main British Indian centres in Upper Canada. Sketch by James Walsh,

about 1804.

(William L. Clements Library, Ann Arbor,

Michigan.)

|

The irregularities in the Indian Department under Elliott at Fort

Malden were exposed for the third time over the requisition for goods to

supply the Indians at Chenail Ecarté during the winter of 1797-98.

Elliott requested supplies for 534 Indians, but McLean received a return

of Indians at Chenail to the number of 160 from Lieutenant Fraser, whom

the commandant had sent to check the actual numbers.22 The

principal chief at Chenail, Chief Bowl, supported Fraser's figures. The

false return of Indians by Elliott and the mounting bitter feud with

McLean over provisioning and obtaining bread from the garrison bakery

finally provoked the governor-in-chief, Robert Prescott, to dismiss

Matthew Elliott as Superintendent of Indian Affairs at Fort Malden in

December, 1797.23 Thomas McKee was appointed to succeed

Elliott.

The McLean-Elliott feud reflected the new policy of order and

regulation so beloved by the peacetime army. Elliott, who had served

the Indian Department faithfully for nearly 20 years in times of crisis,

undoubtedly did not realize that the power of the department during the

quiet years was to be curtailed, and that a rigid enforcement of

regulations had replaced the more usual practice of laxity in which the

attainment of a degree of personal profit was not considered

unwarranted. Dismissed without the benefit of a proper investigation, Elliott

became in effect the scapegoat for the common peculiarities of the Indian

Department in Upper Canada. His conduct was not unlike that of most of

the other members of the department, notably McKee. For the next 10

years Elliott was preoccupied with attempts to clear himself and obtain

reinstatement.

III

In addition to the peace negotiation with the upper lakes tribes at

St. Joseph and the unfortunate Elliott scandal at Fort Malden, the

Indian Department was confronted with another type of problem in the

form of a dispute with Joseph Brant over the sale of the Grand River

lands. The Haldimand grant of 1784 had provided the Iroquois with a

"fertile and happy retreat" on the Grand River as a substitute for the

loss of their traditional homelands in New York during the American

Revolution. But by 1796 less than 2,000 Iroquois, mostly Mohawk, had

taken advantage of the opportunity to live on this large tract of about

570,000 acres. This discouraging situation was compounded because of the

gradual yet steady advance of white settlement in Upper Canada which

began to surround the reserve. Game became scarce in the Grand valley,

and Iroquois repugnance at being reduced to the status of yeomen

resulted in economic depression for the Indians at Grand River.

In an apparent effort to alleviate the Indians' plight, Joseph Brant

devised a plan whereby the future welfare of the Grand River Iroquois

could be assured. The Mohawk leader rationalized that the sale of large

sections of the reserve to British and American purchasers would provide

the native people of the Grand valley with a sufficient fund for their

future needs. The argument was convincing because such a large area was

not needed by the Indians who were indifferent to cultivating the land.

As a successful step in achieving his aims, Brant acquired the power of

attorney in 1796 to sell the Indian lands along the Grand River, and

this power was acknowledged and signed by 35 chiefs of the

confederacy.24 To finalize the business transactions, Brant

held a large council with William Claus, superintendent of Indian

affairs at Fort George, in November, 1796, at which the Mohawk

entrepreneur argued for a legal deed to the Grand River lands of the

Iroquois.25 Brant contended that the Haldimand grant of 1784

not only constituted the creation of an estate in fee simple for the

Indians, but recognized the Iroquois confederacy as a distinct nation,

competent to arrange its own affairs with other sovereign states such as

Great Britain and the United States.26

William Claus and the Indian Department, representing British

interests, countered that the Six Nations, Brant's arguments

notwithstanding, did not enjoy the status of a sovereign nation.

Haldimand's actions, replied Claus, should not be construed as the

authority to dispose of Indian property without the king's approval.

Indeed, the question of the sale of Indian lands had been settled by the

royal proclamation of 1763, which stated in part:

And whereas great Frauds and Abuses have been committed in

purchasing Lands of the Indians to the great Prejudice of our Interests

and to the great Dissatisfaction of the said Indians; . . . to prevent

such Irregularities for the future, and to the end that the Indians may

be convinced of our Justice and determined Resolution to remove all

reasonable Cause of Discontent, We . . . require, that no private Person

do presume to make any Purchase from the said Indians of any Lands

reserved to the said Indians, within those parts of our Colonies where,

We have thought proper to allow Settlement; but that, if at any Time any

of the said Indians should be inclined to dispose of the said Lands, the

same shall be Purchased only for Us in our Name.27

Although the proclamation acknowledged the validity of Indian land

title, or native rights of prior occupancy, it did not accept the idea

of Indian sovereignty overall lands not formally surrendered to the

king.

The reply of Claus infuriated Brant who argued in vain that the

Iroquois could no longer survive exclusively on hunting, and that their

only recourse was to sell parts of the grant so they might obtain some

form of financial relief. The debate continued for months and grew

increasingly bitter. By June, 1797, wild rumours were spreading in Upper

Canada that the Iroquois were angry because they could not sell their

lands on the Grand River and that they might raise the hatchet in

retaliation against the king's subjects. Further unconfirmed information was

received that the French and Spaniards were planning an invasion of

Upper Canada from the Mississippi.28 In response to these

alarms, and following the earlier instructions of the Duke of Portland

of the Home Department, Lieutenant Governor Peter Russell held an

important meeting with his executive council at Government House in

York. The board unanimously agreed to capitulate to Brant's demands

provided that the Indians formally transferred to the crown their

"interest" in those Grand River lands which they wished to sell. The

Indians readily agreed to this proviso and the transfer was arranged by

February, 1798.29 In return the crown sold the designated

tracts, approximately 352,000 acres, to the various individual white

purchasers with whom Brant was dealing. Although Brant insisted that he

was acting on behalf of his people, his personal wealth was

considerably augmented as a result of the sale, and in later years the

Indian Department noted the destitute condition of the Grand River

Indians.30

IV

With the exception of the McLean-Elliott feud and the controversy

over the sale of the Grand River lands, the Indian Department in Upper

Canada experienced an unusual period of quiet between the years 1796 and

1807. At St. Joseph, in March of 1798, Peter Drummond requested

£1,700 worth of presents for the Indians who appeared to have

completely adapted to the British change over from

Michilimackinac;31 and at Fort Malden, McLean wrote lengthy

despatches outlining the stages of development of the new post and of

the building and construction of the Indian Department storehouses and

council house.32 About a year after the dismissal of Elliott,

Governor Prescott produced a return of issued provisions for 1797 and

1798 at Amherstburg and Chenail Ecarté. The figures showed a saving in

1798 (the year Elliott was no longer with the department) of 21,000

rations of provisions, 1,000 gallons of rum and 71,000 bushels of corn,

amounting to upwards of £3,000, and that the Indians had actually

received more in 1798 than in the year before.33 This

inventory sealed the already damaged career of Matthew Elliott for many

years.

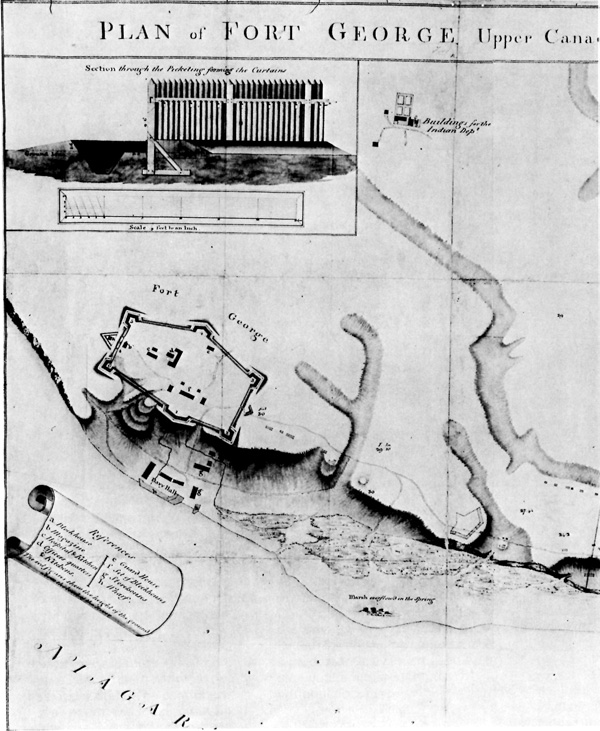

23 Structural plan, Fort Goerge,

1799. Note British Indian Department buildings, upper centre.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

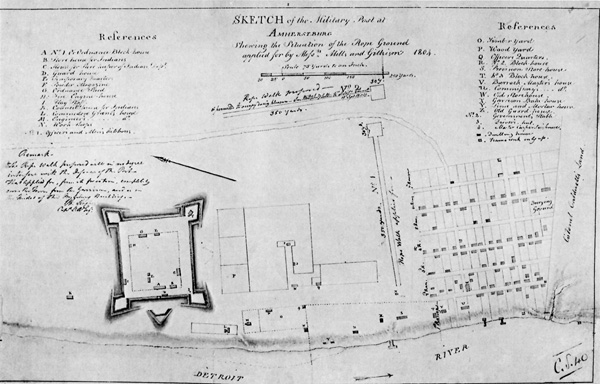

24 Fort Malden (Amherstburg), 1804,

another of the main British Indian Department frontier

posts. Note B and C, storehouse and building for

Indian Department.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

The next few uneventful months were soon shattered on 15 February

1799 by the death of Alexander McKee at his home on the Thames River.

His passing initiated a distasteful dispute as to whether the patronage

of the Indian Department should be under civil or military control. In

Halifax, the Duke of Kent, commander-in-chief of all his majesty's

forces in North America, appointed Colonel John Connolly as successor.

But the new lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, Peter Hunter, supported

by Sir John Johnson in Montreal, argued for William Claus. During the

interim J. Baby, A. Grant and Thomas McKee were appointed as temporary

administrators of the Indian Department until further

orders.34 Hunter Johnson and other senior officials of the

department insisted that the new deputy superintendent general must be,

like Claus, a man of considerable ability and experience regarding

Indian affairs. The choice of Connolly, they maintained, was cleanly

political, and his appointment was unwise because a lack of training and

knowledge in the tactful art of Indian affairs could seriously

jeopardize His Majesty's Indian interests in the Northwest.35

Opinions were exchanged for more than a year until 24 July 1800 when

William Claus was finally accepted and appointed as colonel and deputy

superintendent general. He held the position with honour and skill until

his death in 1826.

With the appointment of William Claus the Indian Department settled

back into the interminable tedium of Indian councils, gift giving, and

pledges of British friendship. At Fort Malden, McLean decided that a

reduction of the costly Indian presents would be desirable, particularly

since the Americans were not pouring out supplies on attempting to

detach the tribes from the king's interest.36 Thomas McKee

opposed the reductions and regarded the distribution of gifts as vital.

If the traditional policy was not continued, he cautioned, it "may

operate to the diminution, if not the total extinction of our influence

and may infinitely prejudice H. M's Indian Interest in these

parts."37 The wisdom of McKee's advice was to be revealed

later.

By the end of 1800 the years of friendly Anglo-American relations and

an indifference toward the Indians produced a detached and relaxed

attitude on the part of the British army in Upper Canada. The

distribution of forces38 illustrated the apparent lack of

concern for defence:

Kingston 102

York 143

Fort George 243

Fort Malden 118

St. Joseph 38

For the Indian Department, the major concern continued to be the

Grand River lands. In three major councils at Fort George in 1803, 1804

and 1806, the Iroquois argued relentlessly for their legal right to

lease more and more of their lands in order to gain a financial redress

from poverty.39 But, although the Northwest and frontier of

Upper Canada were quiet, relations between Great Britain and the United

States at sea were rapidly deteriorating after 1803. With the renewal of

war in Europe, the British government adopted a maritime policy which

seriously damaged the commercial shipping of neutral nations.

Confiscation of cargoes and impressment produced a wave of anti-British

feeling in the United States, with demands by an aroused American

public for a redemption of national honour.

|