|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 14

The British Indian Department and the Frontier in North America, 1755-1830

by Robert S. Allen

The Indian Department and the Northwest in the War of 1812 (1807-15)

I

The Chesapeake Affair of June, 1807, and the bellicose American

reaction destroyed the placid life in the weakly defended settlements of

the Canadas and produced fear of invasion.1 The position of

Upper Canada was particularly precarious because the defensive strategy

devised by the War Office and outlined to the new captain general and

governor-in-chief of British North America, Sir James Craig, was to

preserve the fortress of Quebec and subordinate all other

considerations.2 Since the garrisons in the upper province

were woefully inadequate (even as late as November of 1808 a strength

return of only 411 rank and file was shown), it became abundantly clear

that once again the future security of Upper Canada was to be dependent

on the allegiance and fighting qualities of the Indian tribes of the

Northwest. As a result, the heretofore waning prestige and respect for

the Indian Department was quickly and wholeheartedly revived by the

British.

During the winter of 1807-08, Craig developed a native policy to meet

the alarming situation in the Northwest. He corresponded frequently

with Francis Gore, the worried lieutenant governor of Upper Canada,

and issued various instructions that were to guide the conduct of the

Indian Department for the next three hectic years. Craig reasoned that

in the event of a war, the Indians would not be idle, and if England did

not use them, they would undoubtedly be "employed against us." Therefore,

he continued, the Indians must be conciliated by the British, but their

chiefs must be persuaded not to engage in a premature attack on the

Americans. Thus the agents should avoid making any commitment with them,

at least in "public."3 In another despatch the governor

reminded Gore of the "long-lasting ties" between the king and the

tribes, and suggested that provisions could be supplied to the Indians

to enable them to protect themselves against the Americans who

"obviously desired to take their country." Craig stated further that

the officer of the Indian Department must be diligent and active,

the communication must be constant, these Topicks must be held up to

them not merely in Great Councils and public Assemblies, they should be

privately urged to some of their leading men, with whom endeavours

should be used to lead them to a confidence in us.4

The dual native policy of Craig, one public and one private, was very

reminiscent of Haldimand's successful efforts in 1783. As before, agents

were to court and secure Indian loyalty to the king, and thus preserve

British imperial and territorial jurisdiction in the Northwest by

confounding the expansionist ambitions of the United States. Gore fully

supported the plan and ordered William Claus to Fort Malden, where he

was to assemble the chiefs, "consult privately" with them and remind

them of the "Artful and Clandestine manner, in which the Americans have

obtained possession of their lands, and of their obvious intention of

ultimately possessing themselves of the whole and driving the Indians

out of the Country."5 However, the officers of the Indian

Department were cautioned to dissuade the tribes from any warlike action

until or unless the British should be at war with the United States.

To achieve a more positive assurance of the successful

implementation of his policy, which required delicate and intricate

negotiations with the various tribal leaders, Craig desired officers of

experience and high quality in the Indian service. This was particularly

important since

The Indian Nations owing to the long continuance of Peace have

been neglected by us, and from the considerable curtailments made in the

Presents to those People it appears, that the retaining their attachment

to the King's Interests has not of late years been thought an object

worthy of serious consideration.6

For the British Indian Department, Fort Malden at Amherstburg was the

key Indian centre in Upper Canada. But, unfortunately, the

superintendent, Thomas McKee, was seldom sober and his excessive rum

drinking had drastically undermined his influence with the Indians. As

time was critical and tactful diplomacy vital, Matthew Elliott, "the

only man capable of calling forth the energies of the Indians," was

reinstated as superintendent.

II

The spring of 1808 initiated the annual pilgrimage of the various

Indian bands to the three western British posts, and the officers of the

Indian Department anxiously looked forward to holding secret councils

with them. At Amherstburg on 25 March a group of Shawnee under Captain

Johnny Blackbeard and the Buffalo assembled to hear the British

rhetoric. Like Sir John Johnson in 1782-83, and Dorchester, Simcoe and

Alexander McKee in 1794, William Claus began anew the old diplomatic

rituals. The Shawnee were told that the king was trying to maintain

peace with the Americans, but if he failed, the Indians could expect to

hear from the British, and together they would regain the country taken

from them by the Americans.7

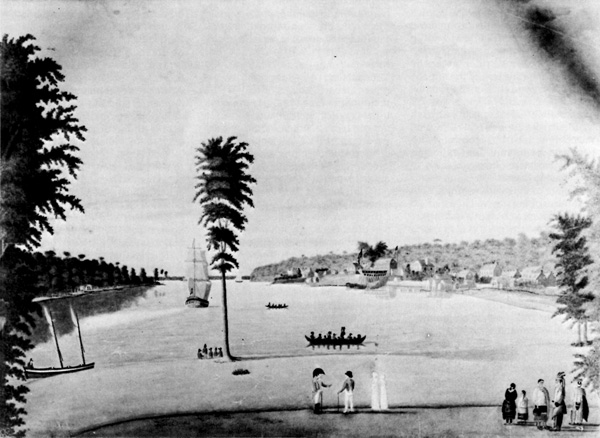

25 Fort Malden, Amherstburg, and Navy

Yard and Detroit River, 1812, by Catherine Reynolds.

|

The work of regaining the affections of the Indians gathered

momentum and in July, 1,000 warriors with about 100 chiefs, including the

influential Shawnee leader Tecumseh who carried on Joseph Brant's dream of

a united Indian confederacy, met with Lieutenant Governor Gore, Claus

and Elliott at Amherstburg. Although the innocuous public councils were

conducted with the greatest decorum, formality and military pomp as in

1783, the "private communications with confidential chiefs, afford . .

. hopes, of a cordial assistance if we show ourselves in any force to

join them."8 To the delight of Gore and Craig, Tecumseh

informed Claus that the different Indian nations were collecting on the

Wabash in order to preserve their country from any encroachments. But

the Shawnee leader spoke a great deal about the Fallen Timbers-Fort

Miami fiasco, and reminded Indian Department officers of the many chiefs

who fell because of that action. Gore realized

that the Indians would have to see actual signs of British military

strength before they would act firmly on the side of the king. However,

the native policy inaugurated by Craig, in which the British engaged in

winning the support of the Indians within American territory, was an

unqualified success. The visit of more than 5,000 Indians to Fort Malden

in the autumn of 1808 was the culmination of 12 months of work and

preparation, and indicated clearly the extent of the

achievement.9

In spite of the overwhelming eagerness of the Algonkian tribes of the

Northwest to accept a realignment with the British and fight the

Americans again, the Iroquois of Upper Canada were not so enthusiastic.

They had suffered cruelly during the American Revolution, particularly

in Sullivan's campaign of 1779; and although Joseph Brant had died in

1807, he had taught the Iroquois to remember the two bitter lessons of

1783 and 1794 when the British had abandoned the Indians to the mercy

of American expansion. Thus at a gathering in the Indian council house

outside Fort George in August of 1808, the Iroquois told William

Claus

of the great distress they are in for Bread... that they had come

to a Determination to sit quiet in case of any quarrel between the King

and America and not to spill the Blood of the white men, and that their

Friendship for the King was firm.10

In fact at two further meetings in March, 1809, the Iroquois

complained vehemently about the difficulties they were having with the

white settlers around Newark, who had squatted on their lands, stolen

their hogs, worked their horses, given them no redress and told them

that the Indian possessed no land.11

III

The renewed power of the British Indian Department accentuated by

their skillful managing of the various tribal councils in 1808 was

evidenced by the "Askin Affair" during the winter of 1809-10. John

Askin, Jr., acting superintendent and storekeeper for the Indian

Department at St. Joseph was charged with pilfering and accused of

committing other misdemeanors by Lieutenant Dixon, the military

commandant at that post. Gore referred the matter to Elliott, who was of

course well acquainted with such problems. Elliott thought that the

suspension of Askin would make an unfavourable impression on the minds

of the Indians, and since every exertion at this time was required from

the officers of the department, the reinstatement of the storekeeper

should become effective immediately.12 Gore complied, and to

maintain harmony between the army and the Indian Department, another

officer was sent to replace Dixon.13 By 1810 the humiliations

experienced by the Indian Department during the "quiet years" seemed

vindicated.

Various tribal delegates constantly visited the British Indian centre

of Fort Malden, Amherstburg to pledge their support to the king and to

receive gifts and provisions in return. As there were no instructions to

alter policy, the Indian Department continued to win and maintain the

allegiance of the various tribes. But in the summer of 1810, native

dissatisfaction at American encroachments on their lands, and British

inspiration, made it increasingly difficult for Claus, Elliott and others

to control the Indian appetite for war. In July, 125 Sauk and Fox

arrived at Amherstburg in a wretched condition of poverty and requested

clothing, kettles, guns, ammunition and other necessities. In council

Elliott urged peace, but he excited the Indians by telling them to "keep

your eyes fixed on me: my tomahawk is now up; be you ready, but do not

strike until I give the signal."14 The dramatic oratory of

Elliott was reminiscent, both in tone and content, of the "Tomahawk

Speech" of Sir John Johnson at Sandusky in 1783.

The problem of Indian unrest reached a peak in November, 1810 when

200 Potawatomi, Ottawa, Winnebago, Sauk and Shawnee assembled at

Amherstburg for a council. Tecumseh acted as spokesman for the tribes

and informed the British officers present that

We are now determined to defend it [our Country] ourselves,

and after raising you on your feet leave you behind but expecting you

will push forwards towards us what may be necessary to supply our

wants.15

Elliott was astounded by these words and wrote to Claus stating that

the speech "fully convinces me that Our Neighbours are on the eve of an

Indian War, and I have no doubt that the Confederacy is almost

general."16 Already, 6,000 Indians had been served with

"their annual Presents and Expenditure of Provisions" from Amherstburg,

but Elliott was now fully aware of the potential dangers and endeavoured

to prevent the Indians from engaging in premature hostilities with the

United States.

The November council placed Sir James Craig in a difficult and

embarrassing position. His native policy initiated in 1808 had worked too

well. Thus in a desperate attempt to reverse the native trend the

governor told Francis Gore to instruct the officers of the Indian

Department to dissuade the tribes from their projected plan of hostility

with the United States. The chiefs were to understand clearly that they

"must not expect any assistance from us."17 Gore quickly

relayed the new orders to Claus and Elliott, and added that to leave no

possible suspicion of flavouring the projected hostilities of the

Indians, arms and ammunition should be withheld from those tribes who

advocated war.18

By the summer of 1811 the officers of the British Indian Department

were striving frantically in councils to prevent an Indian war by

attempting to convince various influential chiefs that the time was not

ripe for a rupture with the Americans. But the Indian desire for war

was now unshakable, particularly since they had received a powerful

stimulant in the new religion of the Prophet. The original name of this

Indian visionary and philosopher was Lalawethika and he was the

half-brother of Tecumseh. In 1805 Lalawethika was influenced by

the religious revival taking place among the white settlers on the

northwest frontier and particularly by itinerant Shaker preachers, whose

jerking, dancing and excessive physical activity stirred mystical forces

within him. During a frightful epidemic of sickness among the Shawnee,

Lalawethika was overcome by a "deep and awful sense" of his own

wickedness and fell into the first of many trances, during which he

supposedly met the Indian Master of Life. When he revived,

Lalawethika announced himself to be a prophet and changed his

name to Tenskwatawa (from the saying of Jesus, "I am the door").

The Prophet preached against the use of liquor and pointed to a new

path, "beautiful sweet and pleasant," a pure life which embodied a return

to traditional Indian values.19 His emotional appeals, which

soon broadened into an anti-white doctrine, and his alliance with

Tecumseh inspired almost every tribe in the Northwest that rallied at

the Prophet's town.

Sporadic Indian raids began to harass the American back settlements

along the Wabash River during the spring and summer of 1811. Public

opinion in much of the United States was convinced that British intrigue

and instigation was behind the revival of Indian resistance. An Ohio

newspaper noted that "it appears that there is a general combination of

the Indian tribes that their aim is the inhabitants of these states, and

that they are prompted to these measures by British (Indian) agents,who

constantly excite them to hostility against the country."20

The rapid deterioration of Indian-American and Anglo-American relations

was convincing proof that Craig's new policy of 1811 had not taken

effect.

Following the November 1810 council, Tecumseh continued to organize a

united Indian confederacy and eventually departed for the south in the

summer of 1811 in the vain hope of winning the support of the Creek,

Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee and others. During his absence William Henry

Harrison, governor of Indiana Territory, advanced with a large army

against the Prophet's town. Although Tecumseh had instructed the chiefs

to avoid hostilities, the approach of the Americans caused great

uneasiness among the Indians and they decided to engage Harrison near

Tippecanoe Creek on 7 November. The early morning attack drove the

Americans back, but after two hours of bitter fighting the Indians were

pushed into a swamp and gave up the contest, leaving 38 bodies on the

field of battle. The victors suffered 188 casualties, but claimed

Tippecanoe as a glorious victory and condemned the British for their

participation in the affair since "British muskets were found on the

battlefield."21 Governor Harrison charged in a letter that

"within the last three months, the whole of the Indians on this

frontier, have been completely armed and equipped out of the king's

stores at Malden."22

IV

The Battle of Tippecanoe terminated Craig's 1811 policy of native

pacification. For several months the British Indian Department had

made genuine efforts to prevent an Indian war, but the vacillation of

policy and the long delays in communicating often different instructions

had hampered the effectiveness of the department and confused the

visiting chiefs. The only alternative was renewal of the friendship and

alliance policy of 1808. With the threat of war imminent, Sir George

Prevost, the new captain general and governor-in-chief of British North

America, was anxious for additional troops. The British regulars and

fencibles immediately available in Canada totaled roughly 5,600

effectives, of which only 1,200 were garrisoning the widely scattered

posts in Upper Canada, the area most exposed to attack.23 But

Isaac Brock, recently promoted to the rank of major-general, disliked

the defensive concept long held by the British War Office that Upper

Canada would have to be abandoned in the face of an American invasion.

In early December he wrote a long letter to Provost and argued that the

Indians were eager to avenge themselves upon the Americans, and that a

strong stand could and should be made. If the western Indians were

supplied by the British Indian Department and encouraged to make war,

Brock reasoned, the Americans would be kept too busy to threaten Upper

Canada; but,

before we can expect an active cooperation on the part of the

Indians the reduction of Detroit and Michilimackinac must convince that

people, who conceive themselves to have been sacrificed in 1794, to our

policy, that we are earnestly engaged in the war.24

Once again Indian support was considered vital for the preservation

of Upper Canada. Prevost, however, had been instructed to exercise

forbearance and to avoid offending the United States by any overt act

which might give the Americans justification for war.25

England was engaged in a bitter struggle with Napoleonic France in Spain

and had no interest in provoking a colonial war with America. Therefore

Prevost urged caution, as he was determined not to create an incident.

The conservative attitude of the governor was reflected in the

instructions issued by Sir John Johnson in May "for the Good Government

of the Indian Department." The superintendent general avoided a detailed

discussion of Indian relations, but did urge the officers of the

department to continue "your utmost endeavours to promote His Majesty's

Indian Interest in general."26 Therefore throughout the

spring of 1812, the British Indian Department secretly prepared the

tribes for war.

26 Major General Sir Isaac Brock (1769-1812), military and civil

administrator of Upper Canada (1811-12).

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

The British policy in the years before the War of 1812 of enlisting

the Indians for the defence of Upper Canada was not restricted merely to

those tribes who inhabited the region of the Great Lakes. In the

Minnesota Sioux country, for example, the foremost British fur trader on

the upper Mississippi, Robert Dickson, had volunteered his services to

the king in 1811. During the long harsh winter of 1811-12 Dickson,

prompted by humanitarian and political motives, distributed £1,500

worth of supplies to the starving Indians and this generous act was to

prove most profitable for His Majesty's government.27

Throughout that winter American agents attempted to influence the

Indians by "making them unusual presents of goods and inciting them in

the most pressing manner to visit the President of the United States at

Washington."28 This American agitation and encroachment

threatened the future prosperity of the fur trade in the region. Thus,

motivated by economic self-interest, his Indian

associations29 and loyalty to the British crown, Dickson was

prompted to endeavour to frustrate American intentions.

He began to rally Indian support for the British by sending "belts"

throughout the Northwest "offering every inducement to take up the

hatchet against the United States."30 Evidently he made no

secret of his power and sentiments for Ninian Edwards, the governor of

the Indiana Territory, warned the secretary of war that "Dickson hopes

to engage all the Indians in opposition to the United States by making

peace between the Chippewa [Ojibway] and Sioux and having them declare

war against us."31 Dickson enjoyed a complete success in

allying the Indians to the British cause. The religion of the Prophet,

the encouraging councils with the Indian Department at Amherstburg and

their hatred of the Americans recently accentuated by their losses at

Tippecanoe, drove the tribes into a natural alliance with the British

against the common enemy. As a ruse some of the chiefs accepted the

American invitation to visit Washington early in 1812. But even while

this contingent was en route, 800 Winnebago, Sauk and Fox warriors were

gathering at the Rock River rapids ready to fall upon the American

border settlements.32 The raids commenced in the first days

of spring and by May "all the Americans except two had fled from Prairie

du Chien, in consequence of the avowed hostility of the Savages toward

them."33

The influence and achievements of Dickson encouraged Brock to send

him a confidential query as to the number of Indians he could muster and

the amount of supplies required. The letter reached Dickson early in

June at the Fox-Wisconsin portage. He replied that Indian support for

the king had already been assured, and that he had about 250-300

"friends" who would be ready at St. Joseph about the end of the

month.34 From Green Bay a few days later Dickson despatched a

contingent of Sioux, Winnebago and Menominee under Chief Weenusate to

co-operate with the British at Fort Malden. With 130 other warriors

from these three tribes he marched for St. Joseph and arrived at that

post on 1 July 1812.

At Amherstburg throughout May and June, Elliott and Claus were

continuously engaged in organizing the large numbers of Indians that

were converging on the British post from all regions of the Northwest.

Tecumseh was located near the Prophet's town with 600 more warriors. The

Shawnee leader regretted that the tribes had fought the Americans in the

previous autumn, but he was anxious for the British to commit themselves

openly. In fact to further inflame Anglo-American relations, Tecumseh

visited Fort Wayne on 17 June and told the American Indian agent that he

was going to Amherstburg for powder and lead.35 Thus by June of

1812, as the government of the United States began to push its

cumbersome war machine slowly into motion, a host of Indian warriors,

prepared for battle, waited patiently at the British Indian Department

posts of St. Joseph and Fort Malden for the declaration of war.

V

News of the war reached St. Joseph on 8 July, along with Brock's

instructions for Captain Charles Roberts, the military commandant, to

adopt the "most prompt and effectual measures to possess yourself of

Michilimackinac," and to make full use of the friendly Indians and the

fur traders. Roberts' command consisted of only 45 men of the 10th

Royal Veterans, but he managed to muster 180 loyal fur traders, and with

the assistance of John Askin, Jr., 300 Ojibway and Ottawa who were in

the process of bartering their furs for trade goods. Dickson's warriors

augmented the contingent to over 400 Indians. With this mixed force

Roberts reached Michilimackinac in the early morning of 17 July. The

discovery of the British and Indians surrounding the fort came as quite

a shock to Lieutenant Porter Hanks and the American garrison, who were

uninformed of the declaration of war. Hanks was unprepared for a lengthy

siege and was unwilling to chance a possible Indian massacre. He

therefore agreed to a capitulation which granted his men the honours of

war.36

The loss of Michilimackinac compounded the strain on Brigadier

General William Hull, who was beset with difficulties at Detroit. The

Indians under Tecumseh had rendered logistics impossible, and in an

effort to re-open their supply lines the Americans had suffered two

setbacks in skirmishes at Brownstown and Monguagan on 5 and 9

August.37 Hull realized that only a speedy capture of Fort

Malden would restore the prestige of the United States; thus he wrote

imploring the governors of Ohio and Kentucky to send militia

reinforcements. But at the same time, because of the fall of

Michilimackinac which had "opened the northern hive" of Indians, Hull

ordered the abandonment of the isolated and indefensible Fort Dearborn

(Chicago). Captain Nathan Heald, commander at that post, commenced the

withdrawal of his 100 men, women and children on 15 August: but the

local Potawatomi had received word of the British-Indian successes, and

excited by the prospect of a victory, 400 warriors led by Black Bird

attacked and butchered the retreating column. The few survivors were

ransomed by the British.38

The American reverses, added to their military ineptitude and

tardiness, encouraged Major General Isaac Brock to plan an attack on

Detroit. With 300 British regulars, 400 Canadian militia, and supported

by about 600 Indians under Tecumseh, he effected a bold crossing of the

Detroit River and demanded the surrender of the town. Hull, who was also

the governor of Michigan Territory, was responsible for the welfare of

the inhabitants. The menace posed by the Indians had undoubtedly become

an obsession with him and he feared for the safety of the women and

children. With these problems weighing heavily upon him, Hull

surrendered on 16 August 1812.39

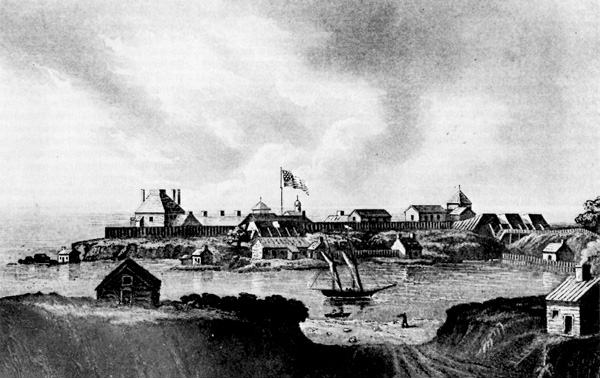

27 The American fort at Niagara

from the British side of the Niagara River, about 1812.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

The victories at Michilimackinac and Detroit provided a quick and

decisive reversal of the military situation, and credit must be given in

large measure to Elliott. Claus and the officers of the Indian

Department who collected and organized the vital native allies for the

British war effort in the opening months of the war. Also these

successes encouraged the Indians already on the side of the king, won

over the waverers, and made neutrals of those who might have joined the

Americans. In September, for example, Brock noted that the Iroquois of

Grand River, who had earlier professed neutrality, were assembling in

great numbers at Fort George. "They appear ashamed of themselves and

promise to whipe away the disgrace into which they have fallen by their

late conduct."40 In fact, for the remainder of the military

campaign in 1812, the Indians provided valuable service in the British

cause as they participated in the Muir expedition against Fort Wayne in

September, and at Queenston Heights in October and Frenchman's Creek in

November along the Niagara sector.

William Claus concluded the first year of the War of 1812 in the

Indian council house near Fort George, encouraging and maintaining

Iroquois allegiance to the king. At Amherstburg Thomas McKee remained

dead drunk, but Matthew Elliott, although over 70 years old, was still

active and worked in close alliance with Tecumseh. In the Northwest,

Robert Dickson, soon to be appointed as "Agent and Superintendent to the

Western Indians,"41 arranged for the distribution of supplies

to the Indians for the winter of 1812-13. He also summoned several bands

of Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Ottawa, Winnebago and Sauk to assemble at Green

Bay in preparation for being sent south as reinforcements. In response a

large force of about 500 warriors gathered under the leadership of the

Sauk war chief Black Hawk, and were eventually despatched to the Detroit

front in order to participate in the 1813 campaign.42

VI

The second year of the war opened in January on the Detroit front

with a decisive and bloody British-Indian victory at Frenchtown in which

the American army of General Winchester was nearly annihilated. "The

Zeal and Courage of the Indian Department," observed the British area

commander Henry Proctor, "was never more conspicuous than on this

Occasion."43 In the Northwest Robert Dickson continued to

recruit warriors to the British cause. At Michilimackinac an aide, John

Askin, Jr., commented that "every Indian that can bear arms on Lake

Michigan and Huron, from Saginaw Bay to Matchedock, will exert himself

to drive away the Americans."44 In April Dickson was at

Prairie du Chien organizing various Indian bands, and by June he had

returned to Michilimackinac with 600 more warriors of which about 100

were Sioux from the Lake Traverse region. Throughout the spring and

summer of 1813, Dickson was responsible for sending 1,400 to 1,500

Indians to the Detroit front.45

Bolstered and encouraged by the vast numbers of these Indian allies

and supported by Tecumseh, the British in early May despatched an

expedition under Proctor against the American post of Fort Meigs on the

Maumee River. A siege and battle ensued in which an American relief

column suffered 200 killed and more than 600 prisoners. Although a total

success for the combined British-Indian force, the weakness of the

Indians as a fighting force became glaringly apparent here. After the

battle most of the Indians, satisfied with their victory, dispersed with

their booty and prisoners, leaving Proctor and Tecumseh with less than

20 chiefs and warriors. The Indian attitude shocked Proctor who was

prompted to declare that "under present circumstances at least, our

Indian force is not a disposable one, or permanent, tho' occasionally a

most powerful aid."46

In July, Robert Dickson finally arrived at Detroit from

Michilimackinac with a force of Ojibway, Ottawa, Menominee, Winnebago and Sioux.

Procter seemed exceedingly happy to have these reinforcements and wrote

enthusiastically that Dickson had "succeeded to the full Extent of his

Hopes among the Indian Tribes."47 For more than two weeks

over 800 Indians lounged around Detroit, gobbling up food from the

British Indian Department stores at a frightening rate, and chafing at

the lack of excitement. Proctor soon realized that another expedition

was necessary in order to preserve tribal interest and respect for the

king; accordingly, a British-Indian force was organized and sent to the

Ohio basin in late July. Proctor explained, "It being absolutely

requisite, for several urgent reasons, my Indian Force should not remain

unemployed, and being well aware that it would not be moveable except

accompanied by a regular Force, I resolved, notwithstanding the

Smallness of that Force to move, and where we might be fed at the

Expense of the Enemy."48

The combined army moved across Lake Erie to Fort Meigs where an

unsuccessful attempt was made to lure the American garrison into an

ambush with a sham battle started in the woods by two parties of Indians

under Tecumseh. The failure of these tactics discouraged Proctor who

decided against attempting an assault on the fort. The Indians soon

became annoyed and impatient at the inactivity and many began to desert.

Those warriors who remained were determined to attack some thing and

suggested the weakly defended Fort Stephenson, a post on the Sandusky

River which guarded Harrison's supply depot. Dickson carried a white

flag to the post and demanded surrender. but the American commander.

Major George Croghan, refused. This determined American response

depressed Proctor even more and he lapsed into indecision once again.

But Dickson had told Black Hawk that the fort would be taken, and

Elliott and other members of the Indian Department warned Proctor that

unless the place was stormed, the British would be unable to depend on

any continuation of tribal support. Thus Proctor reluctantly ordered an

advance in the open against two sides of the fort on 2 August. The

troops "displayed the greatest Bravery," he reported.

the greater of who, reached the Fort and made every Effort to

enter: but the Indians who had proposed the Assault, and had it not been

assented to, would have ever stigmatized the British character,

scarcely came into Fire, before they ran off out of its

Reach.49

After the battle,50 which cost the British 96 casualties,

the warriors abandoned the expedition and quickly returned to Detroit.

Here they were received with dignity and presented with a bountiful

distribution of presents and supplies by the Indian Department in order

to keep them happy and in a warlike mood. The great problem in the

autumn of 1813 for the British was in supplying the Indians with food.

Captain Robert Barclay of the Royal Navy observed that "the quantity of

Beef and Flour consumed here is tremendous there are such hordes of

Indians with their wives and children."51 Barclay soon

compounded the difficulty by losing his fleet and control of Lake Erie

at Put-in-Bay on 10 September. American naval supremacy isolated the

British "Right Division" at Detroit, and prevented adequate supplies

from reaching that post or Michilimackinac.52 Thus the food

problem became even more severe. As early as 6 September, Proctor had

written Prevost about the shortage of supplies and the Indian

dissatisfaction.

The long expected Supplies can not any longer be delayed, without

the most frightfull Consequences. The Indian and his Family, suffering

from Cold, will no longer be amused with Promises, His Wants he will

naturally attribute to our Neglect at least: and Defection is the least

of Evils we may expect from him.53

The destitution and the weakened defensive position of the British

garrison, along with the rapidly advancing American army under

Harrison, convinced Proctor that the forts at Detroit and Amherstburg

together with the various public buildings should be destroyed, and that

the troops and Indians must withdraw.

The decision of Proctor aroused vehement opposition on the part of

the Indians. In a fiery speech in council Tecumseh reminded that officer

of his pledge never to draw a foot off British ground;

but now, father, we see you are drawing back, and we are sorry to

see our father doing so without seeing the enemy. We must compare our

father's conduct to a fat animal, that carries its tail upon its back,

but when affrighted, it drops it between its legs and runs

off.54

The anger, frustration. and bitterness expressed by the Shawnee

leader was shared by the other chiefs who remembered 1783 and 1794. To

the Indians, the British abandonment of Detroit and Fort Malden in

September of 1813 was a third betrayal.

Despite the protestations of the chiefs, Proctor conducted a slow and

agonizing retreat along the Thames River. The Indians reluctantly

followed, and acting as a rear guard, they delayed the American pursuit by

skirmishing with the enemy at Dolsen's and Chatham, but by 5 October the

British were forced to turn and engage Harrison in a major battle near

the Moravian Town, the new home of the Indian survivors of the

Gnadenhutten Massacre of 1782. Many of the Indians had become

disheartened, and contrary to the pleas of Matthew Elliott a number of

Ottawa, Ojibway, Potawatomi, Wyandot and Shawnee deserted. Those

warriors that remained positioned themselves in a swamp to the right of

the British. The American advance was so rapid that the British and

Indians were not yet cleared of Indian women and children nor of the

sick and the baggage. Tired and discouraged the ranks of the 41st fired

two ragged volleys at the charging enemy and then promptly surrendered.

Having in vain endeavoured to call the men to a sense of duty and

seeing no advantage in remaining, Proctor quitted the ground and

narrowly escaped capture by the American cavalry. "I cannot but observe"

he wrote, "that the Troops do not seem to have had that Confidence in

themselves, that they have shewn on every former occasion, and which had

produced a conduct that I witnessed with Pride and

satisfaction."55 The Indians under Tecumseh, however, executed

their part faithfully and courageously and turned the left of the enemy.

But after maintaining the fight against the Kentucky Mounted Volunteers

for about an hour and witnessing the death of their Shawnee leader, the

Indians finally retired through the woods in good order. During the

final phase of the affair "the Conduct of the Enemy's Cavalry was

marked by peculiar cruelty to the Families of the Indians who had not

time to escape or conceal themselves."56

The casualties suffered by combatants vary from account to account.

The British admitted to 12 killed and 36 wounded.57

Eventually 246 assembled at Ancaster, but Richardson states that 600 regulars

were captured.58 This figure contrasts with the reports of

Richard Bullock, an officer under Procter, and Prevost who state that

only 450 British soldiers were available at the start of the

battle.59 All agree that the Indians had 33 killed; and

Harrison indicates that in the American force of some 3,000, only 12 were

killed and 22 wounded.60

The battle at the Moravian Town, more popularly known as the "Battle

of the Thames," virtually terminated the War of 1812 on the Detroit

front. The remnants of the British "Right Division" retreated to

Burlington Heights and linked with the "Centre Division." The Indian

allies of Procter who had not always been reliable, dispersed to their

various towns. As a result of the battle many bands remained neutral for

the duration of the war, whereas others decided to sue for peace with

the Americans at Detroit. For Tecumseh, the Thames provided the death

knell for his United Confederacy—an Indian alliance which proved

like others to be a futile attempt to preserve traditional native

values and regional hunting grounds. When the War of 1812 began, the

Shawnee leader joined the British and was given the title of brigadier

general. He distinguished himself throughout the conflict; but the

British had promised never to yield an inch of their soil, and when

Procter retreated from Amherstburg, Tecumseh knew that his dream was

irretrievably lost. He no longer wanted to live, and he died in the only

way that seemed to him appropriate, covering the retreat of Proctor's

British army for which he had nothing but distrust and contempt.

Although the "Right Division" ceased to exist, their campaigns for

more than a year had provided in valuable service to the British war

effort. Detroit, Frenchtown, Meigs, Stephenson and the Thames had

absorbed the military energies of the states of Ohio and Kentucky and

the territory of Michigan. The American militia and regulars from these

areas would have been of immense value at Queenston Heights, Stoney

Creek, Beaver Dams, Crysler's Farm or Chateauguay. In spite of the

disappointing conduct of Procter and the army at the Thames, it must be

remembered that with the defeat of Barclay, the outnumbered and now

isolated British were without adequate provisions or armament. Thus

under the circumstances, the decision of Procter to retreat was wise and

the harsh criticism leveled against the British general as a result of

the disastrous battle, which ruined his military career, was

unwarranted. Finally the existence of the "Right Division" until October

of 1813 enabled Robert Dickson and the British military to establish a

firm allegiance with the remaining tribes of the Northwest, and this

achievement was to be of vital importance during the last year of the

war.

VII

As Matthew Elliott led the shattered remains of Tecumseh's

confederacy toward Burlington Heights, William Claus was busily engaged

at the head of the lake in preparing the Six Nations of the Grand River,

and a number of Iroquois bands from villages in Lower Canada for the

counterattack against Fort George. In May, 1813, after a gallant defence

against superior American forces and guns, the British retreated from

Fort George, Newark, Queenston Heights, Chippewa and Fort Erie. But the

American advance was checked by bold British action at Stoney Creek and

the Forty in early June, and by a complete victory at Beaver Dams in

which Iroquois warriors under Dominique Ducharme and William Kerr of the

Indian Department forced the surrender of 500 enemy soldiers. Indian

casualties were 15 killed and 25 wounded.61

Throughout the summer of 1813 the Indians provided inestimable

service as 800 of them lurked about the woods in the vicinity of Fort

George and forced the Americans to remain huddled behind the safety of

their breastworks. The fierce reputation of the warriors was so

effective that "a few shots and a little yelling from about 20 of them"

produced a panic in the enemy camp, and fears were expressed that

Proctor and all the Indians had arrived and a general attack was

forthcoming.62 The constant dread of Indian raids on the pickets

and the overcrowded conditions produced sickness and demoralization. The

American general Peter B. Porter wrote disgustedly that "We have an army

at Fort George which for two months past has lain panic-struck, shut up

and whipped in by a few hundred miserable savages, leaving the whole of

this frontier, except the mile in extent which they occupy, exposed to

the inroads and depredations of the enemy."63

28 Upper Canada and the Northwest,

1796-1818.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

By December the American force for the defence of Fort George had

been reduced to 100. The rest of the army, composed mostly of militia,

had drifted away on the expiration of their period of enlistment or

deserted because of the cold weather, sickness, fear or boredom.

Supported by Claus, Elliott and the Indians, the British easily

recaptured Fort George and promptly proceeded to capture Fort Niagara

across the river; and in retaliation for the burning of Newark, the

British attacked and burned the American towns of Lewiston, Black Rock

and Buffalo. For his participation in these latest and successful

exploits Elliott, who had led the Indians against the American towns,

was praised "for his Zeal and activity as Superintendent of the Indian

Department, and I am happy to add that thro' his Exertions, and that of

his Officers no Act of Cruelty . . . was committed by the Indians towards

any of their Prisoners."64

After the counterattack campaigns in December of 1813, Matthew

Elliott, who was nearly 75 years of age, was overcome by a serious

illness and returned to the old house of the late Joseph Brant at

Burlington. Although his sickness persisted, Elliott continued to manage

the affairs of the western Indians from the beach at the head of the

lake. But by early May, his great mental anxiety relative to the Indians

under his charge and his unremitting bodily exertions beyond what his

strength at his advanced age could support so completely exhausted him

that Gordon Drummond, the new British administrator of Upper Canada,

feared that "His Majesty has lost one of his most faithful and Zealous

servants."65 Indeed although his physicians had despaired for

some time and had actually "given him over for three successive days."

Elliott stubbornly clung to life and lingered until 7 May 1814, when he

finally died.

With the death of Elliott and the bad health of William Claus, the

appointment of William Caldwell as superintendent to the western Indians

and acting deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs became effective

immediately.66 Both Riall and Drummond had insisted that

Thomas McKee, the obvious choice as successor, not be appointed as he

had been "getting shamefully drunk" on the beach, causing a great deal

of mischief among the Indians by "speaking to them improperly," and

allowing liquor to be sold to them in great quantities, which "renders

them outrageous and easy to be worked upon."67 Thus for the

remainder of the war on the Niagara front, Claus and Caldwell conducted

the affairs of the Indian Department, but unfortunately these two men

became embroiled in a controversy with "Chief" John Norton over the

jurisdiction of the Indians during the hostilities.

VIII

William Claus had always maintained that the Indian Department should

possess sole jurisdiction and authority over Indian affairs. But the

British military found this argument difficult to accept, particularly

as the large expenditures and bountiful distribution of presents to the

Indian allies came from the army supply stores. Thus during the War of

1812 the problem of authority over provisioning the Indians became acute

and was not finally settled until October, 1813, when a "General Order

Affecting the Awards of Presents to the Indians Warriors" was posted.

By this order the Indian Department was told to co-operate with His

Majesty's officers or any "Chief of Renown" who enjoyed the confidence

and possessed influence over the warriors; and to comply with the

requisitions for presents by the military officer in command where

Indians served.68

To William Claus and the Indian Department the general order was a

victory for one "Chief of Renown," John Norton, who had continually

attempted to undermine the influence of the department since the

beginning of the war. Originally from Scotland, Norton first arrived in

Canada as a private in the 65th Regiment and was discharged in 1788. He

served for a while as a trader along the Miami River, but in 1795 Joseph

Brant took the young man to the Grand River where he eventually became

an interpreter to the Mohawks at Fort George. In 1800 Norton resigned

this appointment and returned to the Grand River and assumed the

customs and manners of an Indian. By 1812 he had gained considerable

influence among the Mohawks, and had attained the status of an Indian

leader of repute.

During the War of 1812 he unquestionably served the crown as an

effective servant in several battles. At Queenston Heights, for example,

Roger Sheaffe noted that the success of the British operation "is

chiefly to be ascribed to the judicious position taken by Norton and the

Indians with him on the woody brow of the high ground."69

Norton also participated at Frenchman's Creek in November and

throughout the summer campaign of 1813 along the Niagara front. But

Norton became increasingly angry at Claus and the Indian Department

because of their interference with him and his Indians.70

Clearly, Norton wanted an independent command unfettered by any military

or civil bureaucratic shackles. He did not want to report to Claus,

"only a Deputy of Sir John Johnson," but preferred to reward his Indians

separately. Thus Claus was most disturbed when Prevost, who was always

suspicious of the Indian Department as a jealous clique, agreed in 1813

by the "General Order" to grant a discretionary power to various

officers and chiefs to distribute presents and rewards to the Indians

who fought in the British interest.71 A second blow to the

prestige and power of the Indian Department occurred in March of 1814,

when Chief John Norton was commissioned as "Captain and Leader of the

Five Nations Grand River Indians or Confederates," and given power "to

reward the faithful Services of the Warriors Acting with him, . . . and

that an ample Proportion of Presents be put up Separately for the

Indians of the Five Nations, to be distributed under Captain Norton's

directions."72 Indeed, Norton was allotted three-eighths of

the presents and ammunition which he thought was too little and which

Claus thought was too much. By the spring of 1814, the influence and

popularity of Norton with the British military was decidedly great and

his complete autonomy was assured by Prevost's directive which stressed

that there should be no interference from the officers of the Indian

Department.

Seemingly confident of his omnipotence, Norton was not content with

controlling the Six Nation Iroquois, but endeavoured to extend his

influence over Matthew Elliott's western Indians as well as bribing them

with liquor and supplies. His obvious lust for power alienated the

Mohawk who expressed dissatisfaction at the appointment and conduct of

Captain Norton as their leader; and a number of Iroquois chiefs affirmed

that they have a "Head Man, who the King has appointed and they want no

other" than William Claus.73 Nonetheless Norton insisted

that the disposition of the Indians toward him, notwithstanding the

exertion of the Indian Department and a portion of the Mohawks, was most

favourable.74

In June 1814, William Caldwell held a council with his Indians in an

attempt to resolve any differences. Caldwell told the Indians that if

they wanted to join Norton they must indicate such clearly, since the

Indians could not be furnished with provisions and clothing by both.

Neywash spoke for the Western Indians and observed that "As to the Snipe

[Norton] . . .I can only say, He speaks loud, and has Strong Milk, and

Big Breasts, which yield plentifully."75 But Caldwell was

assured that if he could supply the Indians in an equally generous

manner, they would remain loyal to him and thus to the Indian

Department. Indian diplomacy was never more calculated.

In order to successfully achieve his ambitions of power and

leadership. Norton distributed lavish amounts of presents and supplies to the

Indians in an effort to win their loyalty. The actions of Norton aroused

the indignation and jealousy of the officers in the Indian Department

who had been instructed to carefully ration provisions to the tribes at

this time. Nonetheless Caldwell reported that the department would not

show to our Indians "any anxiety or uneasiness on the subject of their

joining Captain Norton because such conduct would make them suppose

that a Party Spirit and not true Patriotism prevailed amongst us, and

that we could not act without unanimity among

ourselves."76

The feud between Norton and the Indian Department became so strained

that Gordon Drummond directed Claus and Caldwell to take a conciliatory

line of conduct toward Norton as the means most likely to produce a

good understanding between all parties, "particularly while employed

in Cooperation with His Majesty's Troops, against the Enemy of their

Country."77 However all efforts to gain a spirit of harmony

were frustrated and only the termination of the war ended the bitter

friction between Claus and Elliott and John Norton. In fact the unhappy

conclusion to the affair was that Norton became so insolent and

insubordinate that he was finally discharged in 1815. Nonetheless his

contribution, like those of Dickson, Elliott, Claus and Caldwell was

considerable in that he recruited, organized and led an efficient

fighting force of Indians in the cause of the king.

IX

While Norton and the British Department quibbled over the authority

and provisioning of Indians on the Niagara front, significant events,

largely inspired by Robert Dickson, were occurring in the Northwest in

1814. With the defeat of Proctor and the predominant use of British

regulars during the siege of Fort Erie, the only large-scale employment

of Indians was left to the vast and strategically important region of

the Northwest. Although the United States went to war to redress

national honour and capture Canada, the British and Canadian fur traders

of the upper Great Lakes region and beyond, supported by the local

tribes, also saw an opportunity to wage a war of conquest.78

For the fur traders and the Indians, the War of 1812 became a common

struggle to preserve the lands of the Northwest against American

westward expansion.

In the autumn of 1813, after visiting York in order to make the

necessary arrangements for the transportation of provisions and to

receive his instructions as agent and superintendent, Robert Dickson

travelled to the Northwest.79 He spent the bitterly cold

winter of 1813-14 at Lake Winnebago where he encouraged the Indians to

retain their allegiance to the British crown. In a letter to his

ex-fur-trading partner John Awe on Christmas Day, Dickson recounted, "I

have seen all the Indians of the Rock River and a good number from

Wisconsin. I am most heartily sick and tired of this distributing of

goods and wish for the spring. I hear nothing but the cry of hunger from

all Quarters."80 In February of 1814, Dickson was "entirely

destitute of provisions," and by March he wrote, "There is no situation

more miserable than to see objects around you dying with hunger, and

unable to give them but little assistance. I have done what I could for

them, and will in consequence starve myself."81 Dickson

managed to survive the winter by eating black bread and roots, and in

April, after overcoming severe physical hardships, he reached the

Fox-Wisconsin portage with a number of loyal warriors.

According to Dickson the American threat from St. Louis was the chief

danger for the British and Indians in the Northwest. "It is unfortunate

that we are required in another Quarter," he confessed; "we should find

something worth fighting for there."82 The thoughts of

Dickson echoed those of the British and Canadian fur traders of the

region who wished to preserve the Northwest for the king, keep their

fur-trading interests intact and allow the Indians to roam freely as

before. This was the British fur-trade strategy. The American offensive

against Prairie du Chien and Michilimackinac in 1814 was precisely what

the British merchants desired, as it kept the Indians at home and

necessitated the forwarding of British regulars to the Northwest. Dickson and

the other traders hoped that if the Americans were decisively repulsed

in the Northwest and peace negotiated with the British in complete

possession of the region, the British fur-trade monopoly could be

secured at the expense of the territorial ambitions of the United

States.

For the remainder of the spring, Dickson recruited Indian warriors,

and at Green Bay he was joined by loyal Sioux, Menominee and Winnebago

bands. In May he despatched the Sauk and Fox to guard the Rock Island

rapids on the Mississippi River against a possible American attack which

he feared might come from St. Louis. Early in June, Dickson and 300

warriors arrived at Michilimackinac where Lieutenant Colonel Robert

McDouall, the military commandant of that post, held a large and

impressive council with the Indian bands who pledged their support to

the king. The Sioux chief Wabasha spoke for the western Indians and

stated in part that "We have the good fortune to have 'the Red Head'

[Dickson] for a friend, who in spite of the barriers which the Americans

have made, always found a passage to come and save the Indians from

perishing."83 Other chiefs praised "the courage and good

heart" of Dickson, and Prevost reported that "most of the Indians would

have been lost to the British cause had it not been for the judicious,

resolute and determined conduct of Mr. Dickson and his foresight and

promptitude in forwarding supplies after Procter's

defeat."84

Since Michilimackinac was the key to the Indian country of the upper

Mississippi valley, the retention of the island fortress was imperative

for the British, particularly as the maintenance of the tribal loyalty

and the defence of that vast country were at stake. But Michilimackinac

was but one of two doors to the Northwest, and the Americans had control

of the other at St. Louis. In fact, the Americans planned a twin

offensive in 1814 against Prairie du Chien and Michilimackinac in an

attempt to gain hegemony over the entire area. One prong was assembled

at St. Louis under General Clark, the governor of Missouri Territory.

This force ascended the Mississippi in May, and meeting only feeble

resistance from the Sauk and Fox at Rock Island, the Americans pushed

toward Prairie du Chien and captured the town on 2 June.85

After constructing a stockade which he named Fort Shelby, Clark,

apparently content with his success, returned to St. Louis but left a

small force to guard the town and the new post.86

The news of the capture of Prairie du Chien reached the British at

Michilimackinac on 21 June. Robert McDouall saw immediately the

necessity of endeavouring by every means possible "to dislodge the

American General from his new conquest, and make him relinquish the

immense tract of country he had seized upon in consequence and which

brought him into the very heart of that occupied by "our friendly

Indians".87 Thus at the risk of weakening his own position.

the British commander despatched an expedition under William McKay, a

leading fur trader in the region, to retake Prairie du Chien. Both the

British military and fur-trade interests had no alternative, for if the

Americans were allowed to remain in possession of the area,

there was an end to our connection with the Indians. . . . tribe

after tribe would be graned [sic] over or subdued, & thus

would be destroyed the only barrier which protects the Great trading

establishments of the North West & the Hudson's Bay Company. Nothing

could then prevent the enemy from gaining the source of the

Mississippi, gradually extending themselves by the Red River to Lake

Winnipeg from whence the descent of Nelson's River to York Fort would in

time be easy. The total subjugation of the Indians on the Mississippi

would either lead to their extermination by the enemy or they would be

spared on the express condition of assisting them to expel us from Upper

Canada.88

The small British force was joined en route by voyageurs and Indians.

By the time McKay reached Fort Shelby his contingent had swelled to 650,

of which 120 were "Michigan Fencibles, Canadian Volunteers and Officers

of the Indian Department, the remainder Indians who proved to be

perfectly useless."89 After a curt exchange of notes the

American detachment surrendered on 19 July. The British were once again

supreme in the region and although McKay was not impressed with the

efforts of the Indians who pillaged the houses in the town. he praised

the Canadians and officers of the Indian Department who "behaved as

well as I could possibly wish."90 As a crowning touch and to

complete the victory in a symbolic sense McKay modestly renamed Shelby,

Fort McKay. Following this gesture of victory, McKay promptly retired to

his bed, for he had contracted a severe case of the mumps.

While Prairie du Chien was exchanging flags, a second and larger

American expeditionary force of 700 had sailed from Detroit for

Michilimackinac under the leadership of the hero of Fort Stephenson,

Lieutenant Colonel George Croghan. The five American naval vessels were

delayed by contrary winds and did not reach St. Joseph until 20 July.

After storming the island and finding it deserted, the Americans burned

the fort and public buildings. Following this success they captured a

North West Company vessel, the Mink, burned the fur-trading post

at Saint Marys (Sault Ste. Marie), and murdered a number of Indian

families camped about the post.91 By 26 July, Croghan was

anchored off Michilimackinac, but the high elevation prevented his guns

from engaging the fort. For several days the Americans waited, as

Croghan was reluctant to attempt a landing and assault against the

Indians in the dense and unfamiliar woods.

Although the force for the defence of Michilimackinac had been

greatly reduced as a result of McKay's expedition, McDouall wrote

confidently that "We are here in a very fine state of Defense the Garrison

and Indians in the highest spirits, and all ready for the attack of the

Enemy."92 Croghan finally decided to land on 4 August, and

McDouall, realizing that no British relief column was near, immediately

unleashed the Menominee under Tomah who

commenced a spirited attack upon the Enemy, who in a short time

lost their second in Command and several other Officers . . . . The

Enemy retired in the utmost haste and confusion . . . till they found

shelter under the very Broadside of their Ships anchored within a few

yards of the Shore—They re-embarked that Evening and the Vessels

immediately hauled off.93

The Americans had been exposed to the fire of 140 British regulars

and two field guns, which McDouall has positioned behind a low natural

breastwork, and the furious attack of the Indians in the woods. The

brief but fierce contest had cost Croghan 15 killed and 48 wounded,

whereas British and Indian losses were negligible.94

On their return trip to Detroit the Americans located and destroyed

the schooner Nancy, the only remaining British vessel on the

upper lakes, which had been maintaining communications with

Michilimackinac.95 But the commander of the Nancy, Lieutenant

Miller Worsley, and his small crew managed to reach Michilimackinac by

canoe. Since the American schooners Tigress and Scorpion

had been left to patrol Lake Huron and prevent supplies from reaching

Michilimackinac via the York-Lake Simcoe-Georgian Bay route, Worsley

quickly devised a plan to capture the two vessels. With the assistance

of Lieutenant Andrew Bulger of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, Robert

Dickson and 50 men, all in four small boats, Worsley surprised and

captured the Tigress at the passage of the Detour (near Drummond

Island) on 3 September. Two nights later the unsuspecting Scorpion

was boarded and became an easy victim for Worsley and a British crew in

the Tigress, which was still flying the American

pennant.96 These acquisitions provided the Royal Navy with a

makeshift force on Lake Huron, and if the war had continued until 1815

there undoubtedly would have been a naval battle to decide the

supremacy of the upper lakes.

Michilimackinac was ignored for the duration of the war, but

American attempts to dislodge the British in the Northwest continued against

Prairie du Chien. Early in July, a Major John Campbell and 120 regulars

and rangers had been despatched from St. Louis to reinforce Fort Shelby.

At the Rock Island Rapids this force was attacked and mauled by about

400 Sauk and Fox under the determined leadership of Black Hawk, "a

zealous partisan of the British cause." The Americans suffered 16 killed

and 21 wounded in the engagement; Indian casualties were unknown, but

considered slight.97 The timely arrival of the gunboat

Governor Clark, which was retreating from Prairie du Chien

following McKay's victory, rescued the survivors and the Americans

retreated to St. Louis.

The news of Campbell's defeat angered the Americans, and a second and

larger expedition was organized in August against the Indians at Rock

Island and the British at Prairie du Chien. The commander of this

contingent of 350 men and 8 gun boats was Major Zachary Taylor, future

president of the United States. At Fort McKay the British were aware of

Taylor's movements, and to bolster Indian courage Lieutenant Duncan

Graham of the Indian Department and 30 men, accompanied by Sergeant

James Keating of the Royal Artillery with a 3-pounder and two swivel

guns, were sent down to the villages along the Rock River.98

The small British harrassing force was augmented by 1,200 Fox, Sauk,

Winnebago, Sioux and Kickapoo who swarmed to the side of the king in

eager expectation of another victory.99 In the early morning

of 5 September, Graham, Keating and the Indians surprised and attacked

Taylor's flotilla which was anchored in the shallow waters of the Rock

River. The accuracy of the guns under Keating and the intensity of the

Indian attack under Black Hawk convinced the Americans of the futility

of attempting to destroy the villages and of their inability to

recapture Prairie du Chien. With the Indians in pursuit for about two

miles, Taylor who had lost 3 killed and 8 wounded, retreated to the Des

Moines River and constructed Fort Johnson. In October 1813, he burned

the fort and withdrew to St. Louis.100 No further American

efforts were made against Prairie du Chien, and the British and Indians

remained supreme in the Northwest for the duration of the war.

After receiving word of the repulse of Taylor, Robert Dickson,

accompanied by Andrew Bulger who was to assume command at Fort McKay,

left Michilimackinac on 29 October for Prairie du Chien with five

boatloads of presents and supplies for the Indians.101

Combatting the bitter cold the group reached their destination one month

later. The situation at Fort McKay was critical as the Indians were

starving and the militia garrison was in a mutinous state. Relations

between Dickson and Bulger became strained almost immediately, because

Dickson insisted that the Indians be fed from the king's stores at

Prairie du Chien.102 Bulger countered that he would not allow

Dickson to usurp the authority of the military, and the difficulty was

not settled until McDouall ordered that as of 23 February 1815, "the

Indian Department on the Mississippi is subject to and entirely under

the orders of Captain Bulger.103 McDouall reported that

Dickson had shown a bias in feeding the Indians, and especially the

Sioux bands, and that his conduct had placed the garrison and other

western Indian allies in danger of further starvation. In consequence,

Dickson was recalled to Michilimackinac, deprived of his appointment as

agent and superintendent of the Western Indians, placed under arrest

and detained until the spring when news of peace reached the Northwest.

After his dismissal and release in the spring of 1815, Dickson journeyed

to Quebec where he petitioned Sir Gordon Drummond, the governor, for an

investigation of his conduct during the War of 1812. The case was

referred to the government in London where Dickson obtained a hearing

and a complete vindication. His services to the British cause were

fully recognized and he was rewarded with the commission of lieutenant

colonel and retired with a pension of £300 per year.

29 Tecumseh or Tecumtha (1768-1813).

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Although the Treaty of Ghent announcing the cessation of hostilities

between Great Britain and the United States was signed Christmas Eve,

1814, the British at Prairie du Chien did not receive official

notification of the peace until 20 May 1815. As a result Bulger had

established a defensive position at the Rock Island Rapids, and in the

hopes of discouraging another attack from St. Louis, he sent out several

war parties of Indians in the spring to raid the American settlements in

the surrounding areas. So intense were these raids that one St. Louis

newspaper lamented, "The Indians continue their hostility upon our

frontiers. They have taken more scalps within the last six weeks than

they did during the whole of the preceding spring and summer upon this

frontier."104 Despite the failure of supplies and

ammunition, most of the Indians of the Northwest maintained their

steadfast allegiance to the British who reigned supreme as far south as

Rock River until the spring of 1815.

Toward the end of March, Gordon Drummond sent orders to McDouall to

restore Michilimackinac and Prairie du Chien to the United States as

soon as the garrison and stores could be removed to the new designated

site at Drummond Island. Not unexpectedly, McDouall was extremely upset

and bitter over this British surrender.

Our negociators, as usual, have been egregiously duped: as usual,

they have shewn themselves profoundly ignorant of the concerns of this

part of the Empire. I am penetrated with grief at the restoration of

this fine Island, "a fortress built by Nature for herself." I am equally

mortified at giving up Fort McKay to the Americans, . . . Sir Gordon

Drummond's order is however, positive, and of course leaves no

alternative but compliance.105

At Fort McKay, Captain Andrew Bulger held an Indian council on 22 May

1815. The chiefs were informed of the terms of the peace and of the fact

that the British, as in 1796, were forced to evacuate. When informed of

the situation "the whole hearted man and unflinching warrior, Black

Hawk, cried like a child saying our Great Mother [Great Britain] has

thus concluded, and further talk is useless."106 Two days

later, after distributing presents of pork, flour, cloth, tobacco, iron.

guns, powder, shot and ball to the Sauk and other tribes, and leaving

the Indians "without want" and in a situation more comfortable than in

former years, the British gathered their remaining possessions, burned

the fort and departed. Bulger's force reached Michilimackinac in June,

and on 18 July 1815, having previously removed guns, provisions and

stores to the new post at Drummond Island, McDouall formally

surrendered Michilimackinac to Colonel Butler of the United States

Army.107 British domination of the upper Mississippi valley

of the Northwest was ended forever.

|

|

|

|