|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 14

The British Indian Department and the Frontier in North America, 1755-1830

by Robert S. Allen

The Regime of Sir William Johnson (1755-74)

Prologue

Throughout the long wars for empire between France and England in

North America, the allegiance of the Eastern Woodland tribes was of

paramount importance to the success of both powers. An Iroquois alliance

was particularly sought because of their political and military

strength, and their strategic central location.1 The Iroquois

were kept outside the French fur-trading network, and as a result the

confederacy was in constant conflict with the Huron and Neutral who

controlled the trade from the north and west. Algonkian-speaking tribes

also prevented the Iroquois from usurping the trade along the Ottawa

River; and to the east, the Mohican controlled the Hudson River uplands.

When their own hunting grounds became denuded of beaver by about 1640,

the Iroquois were forced to turn increasingly to the Europeans for

subsistence and the acquisition of trade goods, which rapidly became a

necessary adjunct of their culture, both for trading purposes and for

survival. As a result of the growing necessity for economic dependence,

the formal inauguration of a British-Iroquois alliance resulted at

Albany in 1664. The agreement was not an innovation in the relations

between Iroquois and Europeans, but was merely a continuation of the

policy of giving Albany merchants control of Indian affairs and trade, a

legacy which was inherited from the Dutch who had made an informal

agreement with the Mohawks in the 1640s.2 The importance of

this alliance was that it formed a barrier of frontier defence and as

Thomas Dongan, governor of the royal colony of New York, later observed,

the Iroquois "are a bulwark between us and the French and all other

Indians."3 Although French-Iroquois relations were in a

condition of alternate peace and war during the 17th century as both

sought to control the fur trade with the western Indians, the British

succeeded in maintaining a peaceful cordiality with the Iroquois

confederacy. Thus the Iroquois assisted in asserting the eventual

trading supremacy of the British over the French, as well as providing a

convenient first line of defence for the westward-expanding frontier

settlements of the colonies of New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia

against possible attacks from the French and those western Indian tribes

in alliance with them.

For nearly 100 years the major diplomatic tactics used by both the

French and the British in attempting to achieve an Iroquois alliance

involved religion and trade. Missionaries were as much political

propagandists as spiritual mentors, and religion became an important

tool in serving the ambitions of the imperial rivals in the New

World.4 But, as Peter Wraxall, secretary of Indian affairs

under Sir William Johnson, clearly pointed out on behalf of the British,

"Trade was the foundation of their Alliance or Connexions with us, it is

the chief Cement wch binds us together. And this should

undoubtedly be the first Principle of our whole System of Indian

Politics."5 Thus for the British, supremacy in the Indian

trade became the keystone to any preservation of a balance against the

French. A temporary setback occurred, however, in 1701 when the

Iroquois, following King William's War and a series of French raids into

their country, decided to adopt a policy of neutrality and made treaties

of peace and friendship with both the French and the British.

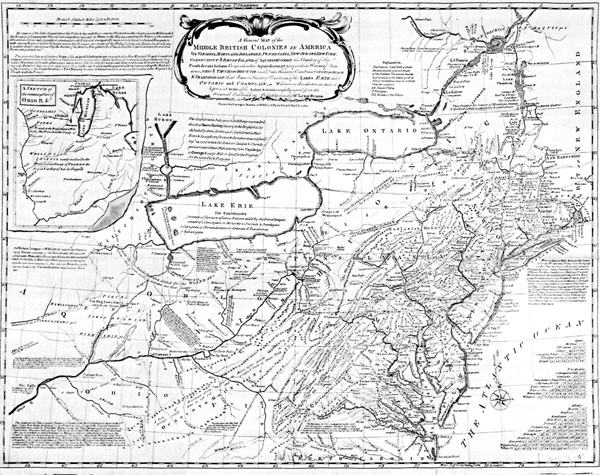

1 A general map of the middle British colonies in America about 1755.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

This Iroquois diplomacy was shattered in the 1740s during King

George's War (1745-48) when British traders took advantage of the

supremacy of the Royal Navy, which kept supplies and trade goods from

reaching New France, and usurped the French role in the fur trade in the

Ohio valley. The Mingo, Delaware, Wyandot, Miami and other tribes which

had previously bartered with the French now turned to the British trader

and his cheaper and more abundant wares. Following the Logstown

conference with the once pro-British Algonkian tribes, the British were

permitted to build trading posts on the Miami, Sandusky and Cuyahoga

rivers, and by 1748-49, were dominant in the Ohio fur trade.6

But almost immediately the Algonkian tribes of the region became alarmed

then hostile at the aggressive nature of the British traders, and

especially at the Ohio Company of Virginia, which was granted 200,000

acres of land west of the Allegheny Mountains by George II for the

purpose of engaging in trade and land development. British expansion and

settlement meant the loss of Indian land and culture, and the tribes

began to seek a renewal of their friendship and alliance with the

French, whose settlements in the west included only those lands

immediate to their trading posts. As early as 1749 George Croghan,

trader and agent for Sir William Johnson, commented that "the Indians

Dos nott Like to hear of their Lands being Setled over Allegany

Mountain."7

The British push into the Ohio valley jeopardized French expansion

westward and threatened their supply line to the upper Mississippi

valley and the Louisiana colony, and encouraged by the Algonkian tribes,

the French redoubled their efforts to regain territorial jurisdiction

over these vast wilderness lands. As a first gesture in this

reaffirmation of sovereignty, Governor Roland-Michel Barrin, Marquis de

La Galissonnière, despatched Captain Céloron de Blainville in the summer

of 1749 to the Ohio to assert French rights. With 200 regulars and

Canadian militia and a band of Indians, all in 23 birchbark canoes,

Céloron descended upon the Ohio country with flags flying, drums beating

and the resounding salute of musketry. Lead plates were buried

throughout the disputed region proclaiming the Ohio lands for Louis XV

of France "by force of arms and by treaties, notably by those of Ryswick

(1697), Utrecht (1713), and Aix-la-Chapelle (1748)."8 Tribes

trading with the British were admonished to cease and warned that those

who persisted in the practice would suffer grave consequences.

French determination to regain control of the Ohio valley culminated

in the destruction of the greatest Indian town in the Ohio country,

Pickawillany, the centre of British trade and influence. For more than

two years following Céloron's tour, the French had attempted

unsuccessfully to incite the neighbouring tribes to attack the powerful

Miami town.

The downfall of this trading centre was imperative for the French if

they were to regain the strategic Ohio lands and recover the allegiance

of the tribes in the region. Finally, in 1752, Charles-Michel Langlade,

a young French fur trader from Michilimackinac possessing strong

influence among the tribes of the upper lakes, persuaded 250 Ojibway and

Ottawa to organize an expedition to the Ohio. Eager for adventure and

plunder, the group stealthily approached Pickawillany on the morning of

21 June. Indian girls working in the cornfields shrieked the alarm, but

the surprise was sudden and complete. Most of the men were away on the

summer hunt and the few that remained, including a number of women and

children, were quickly butchered. Three British traders who were in the

town surrendered, but the attackers stabbed one to death as a grim

warning. The pro-British Miami chief, La Demoiselle (known also as "Old

Briton") was "boiled and ate" as a final symbolic act of

defiance.9

The sacking of Pickawillany temporarily signaled the end of the

British trade in the Ohio. The allegiance of the local tribes, including

the Miami, had now reverted to the French, and British traders scurried

back to the safety of Virginia, Pennsylvania and New York. By the winter

of 1752-53, Governor Barrin's plan for a line of strategic forts and

Indian loyalty was achieved. Although Céloron's expedition and the

capture of Pickawillany had secured the Ohio for the French, these

events were not sufficient to deter the stubborn aggressiveness of the

British traders and the Ohio Company of Virginia, which continued a

declared policy of westward expansion through trade and settlement.

2 Distribution of Indian tribes in the Old Northwest, about 1775.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

The French attempted to discourage British expansion by constructing

Fort Duquesne at the forks of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers, the

entrance through which the British traders gained access to the Ohio

country. Irked by this action, the Ohio Company sent a contingent of

troops under George Washington to reconnoitre. The Virginian mismanaged

the assignment and engaged in a skirmish in which a young French

nobleman, Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville, was killed. After this

unfortunate affair, Washington and his group hastily retreated to the

Great Meadows where he built an entrenched camp called, appropriately,

Fort Necessity. A French relief force led by a grief-stricken and

vengeful brother of De Viliers forced Washington to surrender on 3 July

1754. The exchange of shots in the Ohio wilderness was sufficient to

terminate the short-lived Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. The temporary

respite in French-British hostilities had ended, and in America war was

renewed.

The defeat of George Washington at Fort Necessity coupled with the

memories of Céloron's visit and the massacre at Pickawillany inspired

the pro-French Indians to engage in intensive and continuous raids

against the British settlements along the northern frontier. Anxious to

solve the problems of defence and security against these attacks, the

colonies agreed to meet in a general council at Albany, the centre of

British trade interests. One of the many matters discussed was that of

framing a frontier policy.

The Albany congress of 1754 condemned the private purchase of Indian

lands as a principal cause of uneasiness and discontent among the

tribes. The need for centralized control of western lands had long been

apparent and the congress appealed to the king to create a colonial

union to manage Indian trade, war and treaties, buy and settle Indian

lands and temporarily govern such settlements which would ultimately

become new colonies. In addition, the congress stated that an endeavour

should be made to regain the friendship of those tribes which had

recently defected to the French; that forts should be built in the

Indian country for their protection, to facilitate trade and to bring

them under closer supervision. A suggestion was made to control

expansion and limit existing colonies. The latter suggestion

foreshadowed the Proclamation of 1763 and the British policy of

establishing an Indian barrier state as a form of frontier

defence.10 Finally, and of vital significance, the congress

recommended that those Indians in alliance with or friendly to the

British should be kept constantly under the wise direction of an

appointed superintendent of Indian affairs.

In London, the news of the Anglo-French hostilities at the Great

Meadows prompted the expedition of Major General Edward Braddock with

two regiments to Virginia with orders to drive the French from the Ohio

country. Before proceeding to disaster at the battle of the Monongahela

in the summer of 1755, Braddock, as commander of the British forces in

America, followed the recommendations proposed at the now defunct Albany

congress and appointed William Johnson superintendent of Indian affairs

for the Northern Department.11 The superintendent was to

possess full authority and responsibility for all Indian relations in

the principal theatre of war on the borders of New England, New York and

Pennsylvania. This, according to Johnson, included not only the tribes

of the Six Nation confederacy, but those of the entire Ohio valley as

well.

The Regime of Sir William Johnson

The selection of William Johnson as superintendent was not

surprising. He was born of good family in Ireland in 1715, being the

nephew of Admiral Sir Peter Warren, the commander of the British and

colonial naval forces at Louisbourg in 1745. Johnson came to America in

1738 for the purpose of attending to his uncle's estate at Warrenbush in

the Mohawk valley of upper New York. The young Irishman immediately

initiated a lucrative trading business with the Indians, and within the

year he crossed the Mohawk River to occupy a great tract of land which

he had purchased. Here he built his first home, Mount Johnson, which was

before long to be succeeded by the progressively more impressive

establishments of Fort Johnson and finally Johnson Hall.

Although Johnson pursued the Indian trade and land acquisition with

great vigour and diligence, his exploits were not confined to commerce

and real estate. Toward the end of his first year on the Mohawk in 1739,

he purchased a 16-year-old German indentured servant girl named

Catherine Weissenberg. She was his housekeeper at Mount Johnson, and by

her he sired three children, two daughters and a son, John who was the

heir to his estates and the future superintendent general of Indian

affairs. While at home Johnson seemed content with Catherine, more

commonly known as "Catty," and there is some evidence that he married

her on her deathbed in 1745.12 Yet in the same year as the

birth of Catty's first child, an unknown Iroquois girl bore him a son,

the first of a very long succession of mixed-blood offspring. Most of

them were the products of temporary relationships and the children

remained members of the families of their Indian mothers, but nine of

them, resulting from more enduring attachments, were named in his will

and to each of these he left money, farms, livestock and other

property.

3 Sir William Johnson in council with the Iroquis at Johnson Hall,

Mohawk valley, upper New York. Painting by E. L. Henry.

(Original owned by Mr. John B. Knox, Knox

Gelatine, Inc., Johnstown, N.Y.)

|

Assisted by several agreeable women, many of whom possessed political

influence in council, Johnson enjoyed a long and profitable relationship

with the Mohawk and other tribes of the confederacy. His native

geniality, robust temperament and earthy sense of humour combined with

his fair dealing in trade made Johnson a favourite with the Iroquois,

who gave him the sonorous and appropriate name of Warraghiyagey,

"he who does much business."13 He wrapped himself in their

ceremonial regalia, stamped through their dances, squatted by their

fires, sat with respectful patience through their lengthy councils, kept

his home continually open to them and showered them with gifts. When

Catty died, he chose Iroquois women to take her place, first Caroline

the niece of the great Mohawk sachem Hendrick, and then in 1753, Molly

Brant, the sister of the soon-famous Mohawk orator, statesman and

military leader, Joseph Brant. For 21 years Molly, often called "the

brown Lady Johnson," was recognized as his official consort. She bore

him eight children and was the honoured hostess presiding at a table at

which the guests often included noted Indian dignitaries, governors,

generals and peers of the realm.

The success with which Johnson developed his trading and social

contacts with the Iroquois, which had already made his private fortune

was now about to make his public reputation. Owing to his great

influence among the Iroquois during King George's War, Johnson was

appointed "Colonel of the Forces to be raised from the Six

Nations."14 However, as a result of Céloron's expedition, the

burning of Pickawillany and the defeats of the British at Fort Necessity

and the Monongahela, Johnson was required to exert every ounce of

influence to maintain Iroquois neutrality at least.

Soon after his appointment as superintendent of Indian affairs,

Johnson was commissioned a major general. In September of 1755, with an

army of some 300 totally undiciplined Mohawk and Oneida warriors and

about 300 equally unreliable New England provincials, Johnson fought a

battle at Lake George against Baron Dieskau, the commander of a French

force recently arrived from France. Dieskau's mixed troops of French and

Indians initiated the action by surprising and mauling the vanguard of

Johnson's army. The old and very corpulent Mohawk, Hendrick, had his

horse shot from under him and was bayoneted while frantically trying to

rise. Johnson positioned the remainder of his army behind a makeshift

breastwork of logs and boats, and with this protection was able to

inflict severe casualties on Dieskau's attacking force.15 In

1756, in appreciation of his victory, the king made Johnson a baronet

and appointed him "Sole Agent & Superintendent of the Affairs of the

Northern Indians and their Allies."

As superintendent of Indian affairs, Sir William continued

incessantly to court the allegiance of the Indians, and in 1757, during

a series of lengthy councils, he managed to bind the Iroquois firmly to

the British cause in the war with France in North America. Their

spokesmen declared that they had "not forgot the old agreement with our

Brethren the English, but are determined to hold fast the Covenant Chain

. . . and we shall from this day forward consider the English and

ourselves as one body, one head and one mind."16 As well as

securing the allegiance of the Iroquois, Johnson instructed his agent,

George Croghan, to negotiate the Treaty of Easton in 1758 by which

Pennsylvania agreed to surrender its title to Indian lands west of the

Appalachian Mountains. This treaty temporarily pacified the Algonkian

tribes of the Ohio valley, and the loss of their support "knocked the

French in ye Heade."17

The results of the recent British successes prompted and encouraged

the operation against the French at Fort Niagara. The capture of this

magnificent fortress was vital to the British war effort as it would

curtail the French western fur trade and finalize the indecision of

their already wavering Indian allies. By the summer of 1759, Johnson had

coaxed 900 Iroquois, including many pro-French Seneca who lived near the

post at Niagara and traded with the French, to accompany him on the

British expedition. This was a clear indication that Johnson's long

struggle against French agents for Iroquois allegiance, made difficult

by their clan disunity and neutrality, had been won.

The British, under Brigadier General John Prideaux, laid siege to

Fort Niagara, but a shell from a coehorn burst prematurely and killed

the British officer. The command fell to Johnson. The siege continued as

Royal Engineers constructed lines of trenches and batteries of

artillery. Captain Francois Pouchot, the French commandant at Niagara,

was reasonably confident. French reinforcements from the Illinois,

Detroit and the western posts, including western Indians under the

command of two excellent woodsmen, Aubry and Ligneris, were advancing to

the relief of the fort; but the fate of Niagara was to be decided not on

the siege.

Within two miles of Niagara, the French relief force was surprised

and attacked by the British and Iroquois at La Belle Famille on 25 July.

The French were flanked by John Butler, an assistant to Johnson, and

routed. Aubry, Ligneris and other French officers made desperate efforts

to retrieve the day, but nearly all of them were killed or captured.

Johnson informed Jeffery Amherst, commander-in-chief of the British

forces in North America, of the battle and noted that "I cannot

ascertain the Number of the Kill'd, they are so dispersed among the

Woods. But their Loss is Great."18 Pouchot had no choice but

to surrender, and by the terms of the capitulation the French garrison

was allowed to march out with flags flying, a tribute to their

courageous conduct. They eventually returned safely to France, in spite

of Iroquois protests.

The capture of Fort Niagara and Wolfe's triumph over Montcalm on the

Plains of Abraham in September sealed the fate of France and her hopes

for empire in North America. For Johnson personally, the victory at

Niagara was the culmination of 21 years of literally uninterrupted

lesser successes. The Iroquois were now firmly attached to the British

and Johnson, as superintendent of Indian affairs, spoke for England in

matters concerning native policy.

The great war for empire had raised England to the summit of imperial

power and bestowed on her such remarkable territorial acquisitions as

Canada, the Mississippi and Ohio valley regions and the Floridas, but in

North America the Seven Years' War had illustrated with almost

disastrous results the shortcomings of England's colonial policy of

"salutary neglect."19 Before the conflict the colonial

governments had been responsible for their own defence and their

relationships with the Indians. Throughout the war, the various colonial

assemblies were reluctant to make adequate provisions for the defence of

the frontier and even failed to cooperate one with another or with the

British garrisons. For years New England suffered from Abenaki and

French raids, but received little assistance or encouragement from

neighbouring New York. The Mohawk valley, a prime frontier target for

French and Indian attacks, resisted reasonably well during the Seven

Years' War mainly because of the influence and organizing skill of Sir

William Johnson and the pro-British Iroquois, especially the Mohawk. In

Pennsylvania the pacifistic Quakers, who possessed political and

financial control of that colonial assembly, steadfastly refused to

expend monies on frontier defence. British administrators, both those

stationed in the colonies and at Whitehall, appreciated the deficiencies

of this traditional system and realized that the acquisition of new and

vast frontier lands necessitated alteration of colonial defence policy

in North America.20

4 The Old Northwest, 1740-83.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

After the defeat and expulsion of the French in the Ohio valley, for

example, the tribes there were left at the mercy of American expansion.

As settlers and traders pushed into the region, the Indians became

fearful that their way of life was to be destroyed forever. Concerned

about this rampant encroachment on tribal lands, Henry Bouquet, the

commandant at Fort Pitt, interpreted the Treaty of Easton as equally

binding on Maryland and Virginia, whose lands adjoined the hunting

grounds of the Ohio Indians. He therefore issued a proclamation (October

1761) which forbade any hunting or settlement west of the Alleghenies

unless licensed by provincial governors or the commander-in-chief.

Bouquet enforced the edict by driving away and burning the cabins of

"vagabonds" making settlements in the area.20 Further pledges

were made to the Indians by Johnson at Detroit in 1761, and George

Croghan at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1762. But the policy of

regulating the Indian trade and white settlement, so effectively

initiated at Albany and continued at Easton, had failed miserably by

1763.

The British interest in safeguarding Indian lands as exemplified by

the Treaty of Easton was devised under the shadow of war, but never

heartily approved of by any colonial assembly. Inspired by the news of a

victorious peace with France, settlers and traders, eager for the

acquisition of new lands or fortune, poured into the Indian country

where they used "Every Low Trick and Artifice to Overreach and cheat

those unguarded ignorant People."21 Sir William Johnson both

sensed and feared growing tribal discontent, and in a letter to Amherst

urged a policy of "Steady, Uniform,and friendly Conduct towards them,"

in order to keep the "Indians from forming An attachment to His

Majesty's Interest."22 Amherst, however, never saw a need for

large expenditures on Indian affairs and his control over the purse of

the Indian Department made Johnson's task of conciliating the tribes

most difficult. In addition, and contrary to the sound advice of Sir

William Johnson, Amherst, as commander-in-chief in North America and

thus possessing full control over the Indian Department which was

considered a branch of the military, decided to discontinue the

expensive annual dole to the tribes, thereby adding to native

discontent. This new program of rigid economy was the result of the

financial strain placed upon the imperial war chest during the Seven

Years' War by constantly presenting the Iroquois and their allies gifts

in order to "Brighten the chain of friendship."23

Indian hostility became increasingly overt, and at Michilimackinac,

soon after the British takeover, fur trader Alexander Henry was told,

Englishman, although you have conquered the French, you have not

yet conquered us! We are not your slaves. These lakes, these woods, and

mountains, were left to us by our ancestors. They are our inheritance;

and we will part with them to none. Your nation supposes that we, like

the white people, cannot live without bread — and pork — and

beef! But you ought to know, that He, the Great Spirit and Master of

Life, had provided food for us, in these spacious lakes, and on these

woody mountains.24

Indian opposition and bitterness toward British rule was further

accentuated at the Detroit council in September of 1761 when Johnson

committed a diplomatic blunder. The superintendent arrived at Detroit

with a host of Mohawk dignitaries and friends who patronized the other

tribes insufferably during a long council. Then Sir William Johnson

arose and informed the gathering that he regarded the Wyandot as the

leaders of the incipient western confederacy—at this time a

collection of Algonkian tribes, most of which had been allies of the

French.25 This speech angered the influential Ottawa

confederacy (Ottawa, Potawatomi and Qjibway) and further aggravated

the Indians. Johnson's comments, the fear of the irretrievable loss of

their lands, their anger at British austerity measures aimed partly at

them, and misinformation that the French king was returning to help them

combined to goad the Indians under the leadership of the Ottawa chief,

Pontiac, into open rebellion against the British in May of

1763.26

Although Johnson had repeatedly sent letters and warnings to Amherst

and the Board of Trade in London regarding tribal unrest, the rapid fall

of the British frontier posts at Venango, Le Boeuf, Presque Isle,

Miami, Sandusky, St. Joseph, Ouiatenon and Michilimackinac in May and

June of 1763 surprised the superintendent and the British military. Only

Detroit and Fort Pitt withstood the Indian attacks. Even the Seneca, the

western door of the pro-British Iroquois, took part in the blood-letting

as they massacred the garrison at Venango and ambushed a supply column

at Devil's Hole near Niagara Falls.27

The inability of the various colonial assemblies to agree upon any

joint system of defence, combined with the Indian uprising under

Pontiac and further complicated by the potential danger from the Spanish

and French settlements in the Floridas and Louisiana, made all the more

obvious the need for a plan of frontier defence utilizing British

imperial forces under a central command.28 The British

government responded with a royal proclamation prepared by the Board of

Trade and Plantations in October of 1763. The proclamation established

all lands west of the Alleghenies as an Indian reserve.

It is just and reasonable. and essential to our Interest. . .

that the. . . Indians. . . should not be molested or disturbed in the

Possession of such Parts . . . not having been ceded to or purchased by

Us.29

Although grants of land in the reserve were forbidden without the

express permission of the crown, three new colonies were declared open

to settlement in the hope of satisfying land-hungry migrants— East

Florida, West Florida and a greatly diminished Province of Quebec. Also,

the fur trade was regulated by allowing only licensed traders into the

frontier regions west of the proclamation line.30 The measure

was adopted merely as a temporary expedient in the hope of bringing some

form of imperial control to the prevailing turmoil in

the wilderness.

5 Sir William Johnson (1716-74). An oil by Edward L. Mooney from an

original by Thomas McIlworth.

(New-York Historical Society).

|

Throughout the summer and autumn of 1763, Sir William Johnson held a

number of councils at which he urged the Indians to be calm. At Johnson

Hall in September the superintendent successfully persuaded the

Iroquois, minus the Seneca, to unite with the British. Peace emissaries

travelled to the distant Indian towns to stress the firm and mutual

attachment of the British and Iroquois.31 The horrible

thought of a British-Iroquois force marching against the western tribes

the following spring induced a cessation of hostilities. Johnson,

sensing a desire for peace, arranged a large council at Niagara in July

of 1764, at which he was prepared to discuss a resumption of trade and a

redress of native grievances. More than 2,000 warriors congregated at

the Niagara council. If peace was restored, the superintendent

guaranteed the renewal of the trade upon which the tribes were economically

dependent. Johnson's efforts were entirely successful and the tribes

agreed to terms. Even the Seneca signed a formal peace treaty on 18

July.32 As a crowning touch to mark the end of this most

difficult period of Indian relations, Johnson hosted Pontiac at the

Oswego council in July of 1766. The Ottawa chief, after receiving a

bountiful distribution of presents, shook hands with Johnson and

announced his submission to the British.33 Upon the

termination of tribal hostilities, Johnson turned immediately to the

more enduring problem of the management and regulation of trade and

Indian affairs.

Early in 1764, Sir William Johnson drafted a series of

"observations" to the Lord Commissioners of Trade and Plantations in

England. The Indian problem, argued the superintendent, was caused by

two factors: land encroachments and trade relations. Johnson had

negotiated large and personally profitable land deals with the Iroquois, so

not surprisingly he largely neglected any discussion of the failure of

the Proclamation of 1763 and land infringements. Instead he devoted

most of his paper to devising a solution to trade and political

relations with the Indians on the western frontier. Johnson proposed

that a much stronger Indian Department should be created, independent of

military controls; that with appointed deputies, assistants and agents,

the superintendent should receive full authority over all aspects of

Indian affairs. Trade should be regulated and confined to specific

frontier posts, and although traders were to be permitted to go into the

interior to conduct their business at the designated posts, they were

not to trade at the various Indian villages. In addition, only those

under licence and bond could trade, and the trading of alcohol was

strictly forbidden. Finally the superintendent and his assistants should

act as justices of the peace at these posts.34

The Board of Trade appeared to act favourably toward Johnson's

scheme, and on 10 July 1764 proposed a plan for the "Future Management

of Indian Affairs in America." In London George Croghan, lobbying for

Johnson, was ecstatic over the response and noted that

The sole management of Indian Affairs and the Regulation of Indian

Trade is invested in the Superintendent and his Agents independent of

the Officers Commanding at any of the posts which I make no doubt will

be no small mortification to some people.35

Croghan's comment foreshadowed a recurring and plaguing problem

between the military and the Indian Department regarding the nature of

the control exercised over the tribes by the Indian Department.

Since 1756 the Indian Department had functioned under the control of

the commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America.

Relations between the department and the British military had become

extremely sensitive under Amherst who continually interfered with or

ignored the policy suggestions of Johnson. With the appointment of

Thomas Gage in 1763, however, and his initial laissez faire

approach, friction and misunderstanding between the two groups lessened

and Johnson was able, for a time, to administer his department

unhindered.

Johnson's proposals of 1764 possessed weaknesses, however, and early

hopes for the passage of the plan proved premature. The granting of

licences to traders was marked by illegalities, favouritism and

inter-provincial jealousies. Although Johnson sought to confine the

trade of the Northern Department to specific posts in accordance with

the plan's provisions, both British and French traders violated the post

restrictions and the wholesale evasion of "Johnson's Regulations" soon

became common. The Indians clearly preferred to trade in the woods or at

their villages rather than make long and tiresome trips to the various

designated posts. In addition to these difficulties the crown was

suspicious of granting excessive powers to colonial officials for the

management of the West. A final blow to the ambitions of Johnson's

scheme was the inability of the depleted British treasury to finance a

plan of such magnitude. and the refusal of the American colonies to pay

taxes and thus help defray the expenses of maintaining the military

garrisons. In spite of the lack of support Johnson stubbornly attempted

to implement this more extensive system for the management of Indian

affairs. He appointed agents and commissaries for Oswego, Niagara,

Detroit, de Chartres and Michilimackinac to supervise the trade which

was restricted to these several posts.36 Nonetheless by

1766-67. the scarcity of funds and lack of cooperation, in which even

post commanders and Johnson's agents violated the directives, rendered

the plan inoperative. Immense quantities of beaver pelts were being

brought in from various villages, Alexander Henry and his partner,

Cadotte, bringing in 1,500 pounds alone; and in 1767 over 100 canoes

came to Michilimackinac from the Northwest laden with illegal "Johnson

Regulation" beaver pelts.37

Not only had Johnson's plan for Indian affairs and the regulation of

trade failed, but of greater importance, he complained.

The thirst after Indian lands is become almost universal, the

people who generally want them are either ignorant of, or remote from

the consequences of disobliging the Indians, many make a traffic of

lands, and few or none will be at any pains or expence to get them

settled, consequently, they cannot be loosers by an Indian war, and

abandon their country, they have their desire tho' at the expence of

the lives of such ignorant settlers as may be upon it.38

In addition to the growing dangers of Indian unrest on the frontier,

Johnson was forced to intervene in a clash and scandal between the

military commandant at Michilimackinac, Major Robert Rogers, and

members of the Indian Department over authority, trade and distribution

of presents to the upper lakes tribes. With some difficulty Johnson

managed to appease the military and Rogers was quietly removed from his

post, but only after receiving an attractive and encouraging commission

to seek the Northwest Passage.

Colonial opposition to the Sugar Act (1764) and the Stamp Act (1765)

which the Americans regarded as "repugnant to our Rights and Privileges

as Freemen and British subjects," affected appreciably the Imperial

policy for the interior.39 What had originated as measures to

help lessen the cost of regulating trade and land settlement had

developed into a constitutional issue which involved the affirmation of

the legislative supremacy of Parliament over the colonial assemblies,

With the steady deterioration of Anglo-American relations, British

troops were gradually drained from the wilderness posts to maintain

order in the urban seaboard centres.

After a careful study of the frontier problem, Lord Shelburne,

recently appointed Secretary of State and concerned with colonial

affairs, proposed a plan which represented a departure from previous

policy. Shelburne based his premise on the fact that with the withdrawal

of British troops from the interior, it was impossible to prevent

American westward expansion.40 In addition, the cost of the

military establishment in the West involved maintenance of the forts and

transfer of troops and provisions, as well as the administrative

expenses of the Indian Department and the distribution of presents.

Consequently, as a means of lessening these burdens on the British

treasury, Shelburne urged the restoration of Indian affairs to the

various provinces, and controlled settlement of the interior with the

financial provision of quit-rents to solve the problem of

expense.41

Lord Shelburne's suggestions were referred to his successor Lord

Hillsborough, the first Secretary of State for American Affairs. Working

closely with the Board of Trade and Thomas Gage, the commander-in-chief

of his majesty's forces in America, Hillsborough's thinking was

dominated by three considerations: the reduction of expenses in North

America; the maintenance of a proper political relationship between the

colonies and Great Britain, and the convenient distribution of the

military forces. Thus, the resultant plan of 1768 represented a

precipitate retreat from previous imperial policy with regard to the

Indians. The British army was withdrawn from posts in the wilderness

except for those at Niagara, Detroit and Michilimackinac, and the

authority to manage Indian affairs was restored to the colonies. This decision

was prompted by the government's primary desire to reduce American

expenses.42 Frontier defence had involved an extra

expenditure of £300,000. This amount had been considered

practicable provided the colonies could be encouraged to pay as much as

a third of the amount. But when they continued to balk at paying, it was

decided to deny them the defence upon which they appeared to set so

little value. A secondary purpose was to gather regular forces in

seaboard centres of population where their presence might discourage

the growing American inclination to engage in seditious assemblies and

riots. A third factor was the belief of the British government that if

the colonies were exposed to a general Indian war with which they

themselves must deal, this would restore that sense of dependence on

England which had passed with the defeat of the French.

Throughout the period of colonial supervision (1768-74), the frontier

became increasingly chaotic as a result of the irregular practices and

enroachments on western lands by the traders, settlers and speculators.

The futility of attempting to stem the tide of westward expansion

resulted in a general plan for the formal relocation of the westward

limits of the Proclamation of 1763. The extension of the Indian boundary

line was a victory for a number of influential land speculators and

colonial government officials who envisioned huge personal financial

profits and new empires in the vast and largely unknown interior. The

first major revision of the boundary was negotiated with the Iroquois by

Sir William Johnson at Fort Stanwix in the autumn of 1768. In an effort

to salvage some remnants of their traditional homelands from land-hungry

settlers and speculators, the confederacy surrendered to the crown title

to all their lands south of the Ohio River which "they no longer needed

for hunting."43

By the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, Great Britain made a definite

pledge that the Ohio River should be the frontier boundary forever. This

promise gave the Indian tribes a sense of security against future

aggressions, and for that reason won their neutrality. In the generation

of Indian conflict that followed, tribal spokesmen never ceased to

remind the British and Americans of the solem pledge made by George III

at Fort Stanwix. The boundary, agreed upon in 1768 and reconfirmed by

American commissioners at the Treaty of Pittsburgh in 1775, was to

become the major bone of contention in Indian affairs and was not

finally abandoned by the tribes of the Ohio valley and Great Lakes

region until the Treaty of Greenville in 1795.44

The results of 1768 were unquestionably momentous for both the

Iroquois and Algonkian tribes. The Iroquois received a royal payment of

£10,000, as well as 20 batteaux laden with presents and

food; and although westward migration had been temporarily diverted from

their New York homelands along the Finger Lakes, the negotiations with

the Iroquois had opened to settlement the lands of Kentucky and large

areas in western Pennsylvania and West Virginia. This isolated the

Shawnee who, in their traditional Kentucky hunting grounds, suddenly

found themselves facing a horde of eager white migrants. Because they

were considered wards of the Iroquois, the Shawnee had received no

payment for the 1768 cession. Thus in anger and bitterness, the

frustrated Shawnee joined the Algonkian confederacy centred in the Ohio

valley and disassociated themselves from their supposed benefactors, the

Six Nations. Unfortunately for the Shawnee and contrary to the advice of

John Stuart, superintendent of Indian affairs for the Southern

Department, the Cherokee adopted a policy similar to that of the

Iroquois and attempted to deflect white expansion from their southern

homelands by ceding territory to the north. As a result, by the 1770s

migrants from north and south began to flood into the middle or Kentucky

lands of the Shawnee, who were literally sacrificed to white greed by

the Iroquois and Cherokee.

Disturbed about the growing unrest on the frontier which was created

by the inroads of the settlers and traders, Sir William Johnson held a

number of lengthy Indian councils between 1770 and 1773. His power,

however, particularly among the Algonkian tribes whose lands were

threatened, had been considerably reduced as a result of the plan of

1768 and his part in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, and all attempts to

secure a promise of peace, especially with the now surly and resentful

Shawnee, failed.45 "As far as I can understand these Affairs,"

Gage wrote to Hillsborough, "the Cession [of 1768] is the Cause of all

the Commotions that have lately happened among the Indians." The

secretary replied that he could

only lament that a Measure of the

Utility of which such great expectations was held out, and which has

been adopted at so great an Expence, should have so entirely failed in

it's Object, as to have produced the very Evils to which it was proposed

as a Remedy.46

Hillsborough justifiably complained that the cession had been "so

managed" by Johnson, but what followed added to the danger of his

misjudgements. After a great purchase, prudence would have counseled

slow settlement, but the cession of 1768 was followed at once by plans

for immediate settlement on a grand scale and Johnson, as always, was

at the centre of the new plans. Hillsborough originally hoped for their

success but ultimately opposed them.

As American migrants—among them Daniel Boone—poured into

Kentucky, the Shawnee became increasingly defiant. Thomas Gage, who as

commander-in-chief was most anxious not to employ British military

forces in an Indian war on the frontier, wished these American groups

would "Let the Savages enjoy their Desarts in quiet."47 His

position was incompatible however, with the insatiable frontier

spirit—"a peculiar democratic levelling influence likely to be

arrogant, daring, dangerous and uncontrollable."48 Insult was

added when migrants from Virginia told a number of Shawnee chiefs, now

living in temporary villages along the Scioto north of the Ohio, that

soon these lands would also be surveyed and settled. In September of

1773 a delegation of Shawnee, now supported by Wyandot, Delaware and

some Seneca, told Johnson that if any whites crossed the Ohio there

would be "evil consequences."49 Indeed, further

encroachments by whites provoked scattered raids in retaliation.

The lack of a consistent and unified British plan for the tribes in

conjunction with bitter intercolonial land rivalry and Indian

discontent rendered the situation on the frontier hopeless. The

regulation of trade and land settlement virtually ceased, and the

frontier gradually dissolved into anarchy. In consequence, a

proclamation was issued on 10 March 1774 under order from the crown

which reinstated in the king's name the pertinent portions of the

Proclamation of 1763, prohibiting settlement and land grants in the West and

reaffirming the reservation north of the Ohio River. It also declared

that all land purchases from the Indians since 1763 without royal

licence would be considered "void and fraudulent."50

The proclamation was a preliminary to the Quebec Act of 24 June 1774

in which Great Britain annexed the entire region north of the Ohio River

to the Province of Quebec. Besides the military officers and members of

the Indian Department on the frontier, four new civil governments were

to be created in the region of Detroit, Michilimackinac, Vincennes and

Kaskaskia, with a lieutenant governor for each. Thus the Northwest was

to be preserved as an Indian state and a fur-trade empire. This

proclamation also resolved the problem of the French Canadian

settlements in the Illinois country, giving them the same politico-constitutional

privileges and rights as the French in Canada.51

Until the outbreak of the American Revolution, however, white

migration westward continued unchecked. The Proclamation of 1763 was

ignored; the barrier of 1768 had been washed away by the rushing tide of

settlers, and the Quebec Act was despised by Americans and labelled as

"intolerable." In Kentucky the mutual acrimony between the Indians and

the American migrants was accentuated by the brutal slaying by Americans

of an unsuspecting and peaceful Shawnee family which included a pregnant

woman. By June, increasing Indian retaliatory raids induced the

governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, to call out the militia and declare

a state of war. The Shawnee were immediately joined by the Delaware,

Wyandot and Seneca. Although the war in Kentucky was to terminate

quickly with the result that the Shawnee finally recognized the Fort

Stanwix cession, Johnson was fearful that the remainder of the Six

Nations might join in the hostilities. Therefore in an attempt to

soothe and arrest the Iroquois desire for war, the superintendent

assembled a large council at Johnson Hall in July of 1774. After a long,

four-hour outburst of rhetoric in which he pleaded for Iroquois

neutrality, Sir William Johnson collapsed and died.52

The news of the death of Warraghiyagey resounded throughout

the Indian world and was marked by wailing and rituals of lament. In

many respects his regime was remarkable. As first superintendent of

Indian affairs he had succeeded in developing and maintaining an

organization which was capable of influencing and manipulating the

tribes to suit the interests of the British crown. At the same time

Johnson amassed a personal fortune in land speculation. Iroquois

affection for the man and their influence over the other tribes coupled

with Johnson's calculated and skillful diplomacy in bargaining for

Indian cessions were responsible for his incredible acquisition of

wealth. By using the Six Nations as a fulcrum, Johnson's power and

prestige were enhanced and by scattering agents throughout the various

Indian towns and thus maintaining direct contact with the pulse of

native feeling, he achieved a tightly knit system for the management of

Indian affairs.

At the time of Johnson's death British economic measures had reduced

expenses for the Northern Department to £5,000 per year, and this

included the usual high costs of the annual distribution of presents to

the Indians. As a result, the tribes were in an unhappy mood with

respect to their economic position. Flagrant encroachments on their land

by American migrants followed by Dunmore's War only aggravated their

bitterness. The situation was further complicated by the

dissatisfaction of the Algonkian-speaking western tribes which were angry at the

Six Nation Iroquois for hoarding the Fort Stanwix presents. In response

to these problems the western tribes decided to rid themselves of the

shackles imposed by their Iroquois patrons and to form their own

confederacy. Any type of tribal disunity, however, was catastrophic to

Indian hopes of continuing a traditional existence of hunting and

fishing, and the formation of this second confederacy was to initiate 20

years of disharmony among the native peoples which were to conclude with

their destruction. The events of 1775 were to delay the difficulties of

Indian factionalism, however, and Johnson's department was soon to

face the test of war and the grave responsibility of encouraging and

assisting the tribes in the cause of the king.

|

|

|

|