|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 14

The British Indian Department and the Frontier in North America, 1755-1830

by Robert S. Allen

Indian Confederacy: The Search (1784-93)

I

After the American Revolution, the Indians learned that they had no

right to exist independently or to live where they pleased. By fighting

with the British between 1775 and 1783, the tribes, according to the

official American view and the Treaty of Paris, had forfeited title to

their lands. Thus Indian land was to be considered as conquered and

surrendered territory. The ignorance and frustration of the Indians was

constant. To them, the entire peace treaty of 1783 was incomprehensible.

The tribes had won two glorious victories at Sandusky and Blue

Licks in 1782 and had never been overrun by the Americans. They knew

themselves therefore to be unconquered.1 Also the British in

the Northwest had not been overrun or conquered. How, then, reasoned

the Indians, could the British cede the land of the Ohio region (which

the tribes regarded as their own) to the Americans? Yet the tribes

learned that the United States had been given, by international treaty,

all the land up to the middle of the Great Lakes.2

The British, through the speeches of Sir John Johnson and other

members of the Indian Department, denied that they had forfeited Indian

lands by the terms of the 1783 treaty. What had been transferred to the

United States, they stated, was the exclusive right to buy Indian lands

within the American international boundary, but not the ownership of

these lands which had been guaranteed to the Indians by several prior

treaties, particularly the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in

1768.3

On 15 October 1783, the Confederation of the United States

inaugurated an Indian policy based on the report of James Duane, chairman of

the committee on Indian affairs. The ordinance repudiated the Ohio River

boundary and demanded that the tribes of the Northwest withdraw west and

north beyond the Miami and Maumee rivers.4 The Indians were

told that the land on which they now lived had been ceded by Great

Britain in the Treaty of Paris. Consequently, the Indians were a

subdued people and subject to the wishes of the United States.5

Thus treaties could be negotiated and the tribes would have to vacate

certain lands for settlement. In attempting to establish peace with the

Indians of the Northwest, Congress wished to begin the process of

acquiring the lands between the Ohio and the

Mississippi.6

At the Treaty of Fort Stanwix on 22 October 1784, the appointed

American commissioners, Oliver Wolcott, Richard Butler and Arthur Lee,

managed to assemble the influential Six Nations and negotiate a

settlement. The Iroquois leaders protested to the representatives of the

United States that a definitive treaty could not be concluded without

the presence of the Algonkians — Ottawa, Ojibway, Potawatomi,

Delaware, Shawnee and Wabash confederates.7 This protest was

an effort to maintain Indian unity against American territorial

ambitions as encouraged by Joseph Brant and members of the British

Indian Department at Sandusky in 1783.

The commissioners, however, sternly reminded the Indians that they

were a subdued people and that the king of England had ceded to the

United States all the Indian land as far as the Great Lakes, and by

right of conquest, the Americans could "claim the whole."8

The Iroquois leaders debated the alternatives, but Cornplanter, a noted

Seneca chief, argued that an accommodation must be made with the

Americans if peace was to be preserved, and his rhetoric influenced the

rest. So having been abandoned by the British, now the Ohio valley

Algonkian Indians were sold out by their old rivals, the Six

Nations.

By the terms of the treaty, the Six Nations surrendered to the United

States their ancient territorial claims to much of the land lying west

and north of the Ohio River.9 This provision was contrary to

the prior treaties, proclamations and acts of 1758, 1763, 1768, 1774 and

1775. But of equal importance to the Americans was the knowledge that it

freed the western tribes from Iroquois domination.10 The

western tribes, by right of conquest, were subject peoples of the

Iroquois. However, when the Iroquois divested their claim to the Ohio

country in 1784, the tribes in that region were considered free and

independent and could be dealt with accordingly by the Americans. The

policy of Congress was to terminate land claims tribe by tribe, and thus

disassociate itself from the traditional policy of Sir William Johnson,

who worked through the Six Nations to obtain concessions from the

Algonkian tribes. With the 1784 treaty successfully completed, the

congressional representatives looked forward to negotiating with the

western tribes without Iroquois interference, a policy maxim reminiscent

of the old official British colonial policy of "divide and rule."

At Fort Mcintosh on 21 January 1785, only a few minor chiefs from the

more pacifistic factions of the Wyandot, Delaware, Ojibway and Ottawa

assembled to hear the Americans. George Rogers Clark, back woodsman and

hero of Vincennes, had replaced Wolcott, but the speech read to the

western Indians was the same as that of Fort Stanwix. After token

objection, the chiefs of the tribes represented acknowledged the

protection of the United States and signed away lands north of the Ohio

River.11

At the Sandusky conference in 1783 the tribes had pledged that no

agreement would be made with the United States except through the Indian

confederation as a whole; but at Stanwix and Mcintosh, the various

tribal land cessions resulted in the dissolution, for the moment, of

the united Indian front.

The removal of tribal land claims by the treaties of 1784 and 1785

only complicated the Indian policy of the United States in the

Northwest. Native restlessness and discontent became apparent. The 1784

Iroquois cession angered the Wyandot, Delaware and other native bands

which argued that the Six Nations had no right to cede the Ohio valley

hunting grounds inhabited by Algonkian tribes. Also, the 1785 treaty was

considered invalid by the Ohio valley tribes because the militant

Shawnee, one of the most influential tribes of the region, had refused

to attend the council.

Yet even before the treaties were ratified, American backwoodsmen

swarmed into the Ohio River area—"so fine a country my eyes never

beheld"12—and upon Indian lands not yet ceded. The

attempts by congressional forces to drive these settlers out of the

contested region were futile. The "white banditti" were well organized,

numerous, and firm in the belief of the right of expansion into vacant

forest lands.13

The Indians, however, in spite of their land cessions in the recent

treaties, were prepared to contest the advance of the backwoodsmen.

Captain Johnny, a Shawnee chief, told the Americans at a council at

Wakitunikee that

you are drawing close to us, and so near our bedsides, that we can

almost hear the noise of your axes felling our Trees and settling our

Country . . . the Boundary is the Ohio River, . . . but it is too clear

to us your design is to take our Country from us . . . [we are]

determined to act as one man in Defence of it. Therefore be strong

and keep your people within Bounds, or we shall take up a Rod and whip

them back to your side of the Ohio.14

The resolution of the Indians to defend their country was no veiled

threat. Settlers floating down the Ohio River in flatboats were

repeatedly attacked by various bands of irascible natives.15 Tribal

spokesmen explained to British agents that they had never asked for

peace; indeed, they thought the Americans desired it, and listened to

them only because the Indians were so advised by their father, the

British king. The tribes "had no idea that the Americans looked on them

as conquered people 'till so informed by the

commissioners."16

The general dissatisfaction of the Indians prompted Joseph Brant to

visit the country of the upper lakes in the summer of 1785 and hold

council with the nations. At the assembly the Six Nations implored the

Algonkian tribes to join them in defending their country against the attacks

of the United States and they repudiated the action taken by their

representatives at Fort Stanwix. Although the tribes declared their firm

attachment to the king, British Indian Department agents present

nonetheless advised them not to act precipitately, but to state to

Congress their position and claims.17

Like Pontiac 20 years earlier, Brant was concerned about native

survival, and it was the Mohawk leader's hope that he could combine all

the tribes of the Northwest into a single grand

confederacy.18 Only through solid Indian unity could

effective resistance be made against American westward expansion. But he

knew that what was required to gain Indian acquiescence was a more solid

assurance of British support. Therefore, in order to ascertain exactly

what position his majesty's government would take if serious

difficulties developed between his people and the Americans, Joseph

Brant journeyed to England during the winter of 1785-86.

The arrival of the "noble American savage" in England on 12 December

1785 caused a sensation in British society.19 Although Brant

enjoyed the pageantry and pleasures of London social life, he was

preoccupied with the problems of the native people in America. In a lengthy

introduction to Lord Sydney, Secretary of State of the Home Department

between 1783 and 1789, Joseph reminded the minister of the faithful and

valuable role the Six Nations played in the late American war. The

Indians, he continued, were astonished that the British had forgotten

them at the peace treaty of 1783, and the Americans were violating the

British-Indian pact of 1768. Therefore, Brant urged, would the king

support the Indians in a war with the United States?20

Sydney's reply, three months later was a paragon of British

diplomatic protocol. Certainly the king had the welfare of the Indians

at heart but

His Majesty recommends to his Indian allies to continue united in

their councils, and that their measures may be conducted with temper and

moderation; from which, added to a peaceful demeanor on their part, they

must experience many essential benefits, and be most likely to secure to

themselves, the possession of those rights and privileges which their

ancestors have heretofore enjoyed.21

The language was nebulous enough to imply that Britain would assist

the Indians in a future emergency, but it provided Brant with little

immediate encouragement for a British-Indian alliance against

America.

However, in a secret despatch, Sydney instructed Lieutenant Governor

Henry Hope of Quebec to avoid assisting the tribes openly, but to

maintain a friendly relationship with them since "the very peace and

prosperity of the province depends on it."22

It is utterly impracticable for his Majesty's Ministers to

prescribe any direct line for your Conduct should matters be driven to

the extremity, and much will depend upon your judgment and discretion in

the management of a Business so delicate and

interesting.23

Unquestionably British native policy for America in 1786 was vague.

Nonetheless it did possess the soundness of flexibility and allowed the

local officials in the field to use their own discretion according to

the exigency of the circumstance. Whitehall could then repudiate any

such decision if the action proved harmful to the delicate balance of

Anglo-American diplomatic relations.

Brant returned to the forests of North America in the summer of 1786

to find the native problem acute. During his absence in England the

American commissioners Clark and Butler had summoned the peace faction

of the Shawnee to a council at the mouth of the Great Miami River. In

return for a promise of peace, the Shawnee delegates acknowledged that

the United States was "the sole and absolute sovereign of all territory

ceded by Great Britain in the 1783 treaty."24 In addition the

chiefs signed away Shawnee claims to territory east of the Miami

River.25

The treaties of 1784, 1785 and 1786, based solely on the idea of

conquest, had coerced the Indians into relinquishing all their lands

along the northwest frontier to the United States. Congress was

suspicious of the British activities with the Indians and followed a policy

of counteracting the king's influence among them by attempting to reduce

the tribes to the status of dependent wards. By 1786, however, the northwest

tribes were disgusted with the whole Indian policy of the United

States and repudiated all the treaties made with the congressional

representatives since the close of the American Revolution.26

The Shawnee were particularly incensed against the influx of the

backwoodsmen, and raids commenced along the Ohio River.27

Congress, having embarked prematurely on a policy of aggression, was

financially powerless to combat Indian resistance.

11 Field dress (private), Loyalist corps, Butler's Rangers;

watercolour by Charles M. Lefferts. (New York Historical

Society.)

In an effort to bring some security to the helpless frontier, two

expeditions under George Rogers Clark and Benjamin Logan were organized

by Kentucky, independent of central authority. Clark's action against

the Miami of the Upper Wabash River failed miserably owing to desertion

and lack of supplies, and he was forced to retreat to

Vincennes.28 Colonel Benjamin Logan, however, surprised the

Shawnee and on 6 October 1786 burned their two principal towns of

Maycockey and Wakitunikee (where Captain Johnny had made his defiant

speech in 1785).

Maycockey town raised the "Yanky" colours but to no purpose, as

the army destroyed the town, proceeded to Wakitunikee and destroyed it

and burned the houses of Alexander McKee and Blue

Jacket.29

II

The violence on the frontier alarmed Sir Guy Carleton, Lord

Dorchester, the new governor of Quebec. As a representative of the

British crown he quickly conveyed the message to the Indians that the

king was at peace with the world and was neither prepared nor wished

for war. The Indians, Dorchester urged, must endeavour to secure a solid

peace with the Americans. In a despatch to Sir John Johnson,

Superintendent General of Indian affairs, the governor cautioned that

"All promises (to the Tribes) not intended to be fulfilled must be

avoided."30

In a letter to Lord Sydney a few days later, Dorchester elaborated on

the reason for his concern.

The Americans have made an inroad on the Shawanese country west of

the Ohio, burned some of their villages and carried off some women and

children as prisoners. The town where the Indian Congress was to

assemble was also laid in ashes. The alarm [is] increased by the

report that parties are moving up the Rivers which fall into the Ohio

River from the North and leads to Detroit.31

The governor realized that a prolonged war between the Indians and

Americans was a distinct possibility. Therefore, it was in the national

interest of British North America to maintain at any cost the

allegiance of the tribes of the Northwest, for upon them rested the

retention of the western posts—Niagara, Detroit and

Michilimackinac—and indeed the defence and survival of the upper

Province of Quebec. To achieve this loyalty, the British government

spent over £20,000 per year between 1784 and 1788 on Indian

presents.32 The tribes were provided with ammunition,

muskets, axes, knives, clothing and medals of King George

III.33 Lord Sydney even suggested that it might be advisable

to give the Indians ammunition with which to defend themselves against

the Americans.34

As a gesture of unity and to discuss their mutual problems, the

tribes of the Northwest and the Six Nations gathered for a lengthy

council near the mouth of the Detroit River in December of 1786. Joseph

Brant opened the conference with a speech pleading for Indian unity. The

tribes responded by unanimously and formally denouncing the treaties of

1784, 1785 and 1786. The Indians justified this action by blaming the

Americans who, they contended, held councils wherever they chose

without regard to the tribes and made separate treaties instead of

having a general conference with all the nations.35

11 Field dress (private), Loyalist corps,

Butler's Rangers; watercolour by Charles M. Lefferts.

(New-York Historical Society.)

|

After this lengthy discussion the council, known now as the "United

Indian Nations," drafted an address to Congress. The message began with

a declaration of surprise that the tribes were not included in the peace

treaty of 1783. The king had advised them to remain quiet, observed the

Indians, but unfortunately "mischief and confusion" had occurred.

Nonetheless, the Indians urged a meeting in the spring to negotiate a

treaty of friendship and understanding with the Americans. Meanwhile,

suggested the council, Americans should stop encroaching on tribal

lands across the Ohio River.36

The British, as represented by their Indian Department agents at the

councils, had succeeded in obtaining a loose alliance of the Northwest

tribes. This was a damaging blow to the early Indian policy of the

United States which had planned a programme of divide and rule. However,

Indian unity was shaky at best. At the Detroit council there was

friction over the concession of lands north of the Ohio by the Treaty of

Fort Mcintosh. The Wyandot and Delaware who lived nearest the Ohio, and

who would bear the brunt of an American attack, were prepared to

compromise. But the Shawnee and other western Indians were determined

to stand firm on the 1768 line as the limit of white

expansion.37

During the long, complicated Indian-American debate over recognition

of aboriginal rights, the British maintained a position of remarkable

consistency. In the spring of 1787, Major Robert Matthews, military

secretary to the governor, made an official tour of inspection of the

western posts for the purpose of making a special report for the

information of the secretary of state of the Home Department. During the

course of his travels, Matthews wrote Joseph Brant and gave him a

summation of the official British policy toward the tribes of the

Northwest.

[The king] cannot begin a war with the Americans, because some of

their people encroach and make depredations upon parts of the Indian

country; but they must see it is his Lordship's intention to defend the

posts . . . . On the other hand, if the Indians think it more for their

interest that the Americans should have possession of the posts, and be

established in their country, they ought to declare it, that the English

need no longer be put to the vast and unnecessary expense and

inconvenience of keeping posts, the chief object of which is to protect their

Indian allies, and the loyalists who have suffered with

them.38

The tone of the letter was such that the Indians were to believe that

if the posts were surrendered to their inveterate foes, the Americans,

the traditional life style of the tribes would be doomed. Sydney,

writing to Lord Dorchester, echoed the theme by arguing that the conduct

of the Americans had justified the retention of the western posts. The

British treatment of the Indians, continued Sydney, has always been

liberal and "considering that the security of the Province may depend on

their loyalty, supplies may be augmented rather than leave them

discontented."39 Whitehall was anxious to continue using the

natives as pawns in their dealings with the Americans, and thus retain

British commercial and imperial interests in the Northwest. Yet,

because of tribal resistance and British policy for the frontier, the

United States in the summer of 1787 initiated a policy of appeasement of

the Indian tribes and the public lands of the Ohio valley.

III

The first governor of the American territory northwest of the Ohio

River was Arthur St. Clair, a veteran officer of the American Revolution,

whose appointment became effective on 22 October 1787. The governor

was instructed to negotiate a treaty of peace with the Indian tribes and

"to conciliate the white people inhabiting the frontiers towards

them."40 But there was to be no departure from the former

treaties of 1784, 1785 and 1786, unless a more favourable boundary could

be obtained for the United States, "You will not neglect any opportunity

that may offer of extinguishing the Indian rights to the westward as far

as the river Mississippi."41

St. Clair was a man of limited military and administrative capacity,

but he did realize that if the uneasiness among the tribes of the

Northwest could not be removed, a general war would ensue. In a letter

to Henry Knox, the Secretary of War, the worried governor observed

Whether that uneasiness can be removed I own, I think doubtful,

for though we hear much of the Injuries and depredations that are

committed by the Indians upon the Whites, there is too much reason to

believe that at least equal if not greater Injuries are done to the

Indians by the frontier settlers of which we hear

little.42

In spite of the apparent danger, St. Clair arranged an Indian

council, but he regretted that the finances of the United States would

not permit a more liberal appropriation of money, particularly since the

tribes were receiving large amounts of presents and other inducements

from the British.43 Congress had voted a total of $34,000 of

which $20,000 was to be applied toward the extinguishment of Indian

claims to lands already ceded to the United States, and for purchasing

other lands beyond the limits fixed by prior treaties. Nonetheless,

after a final meeting with Knox, the governor departed for the

"Territory Northwest of the River Ohio."

When St. Clair finally reached the Ohio on 9 July 1788, the frontier

was in a chaotic state. One observer noted that the emigration to

Kentucky and Ohio, termed the western territory, "exceeded the bounds of

credibility." Enterprising New England people in particular, checked in

their commercial pursuits at home, turned to the tempting, though

remote, country and were not deterred by the danger or difficulty in

finding a means of subsistence. In addition, "the present feeble

Congress has little authority over any part of the western country, and it

is doubtful whether the new one may possess the power sufficient for the

purpose."44

Depredations on the frontier became more bold and alarming than

ever. American backwoodsmen butchered a band of migrant Cherokee on the

Scioto; and on 13 July an Ottawa raiding party attacked and plundered

the American supply column carrying the Indian presents for St. Clair's

upcoming council.45 During this summer of violence one young

man, Thomas Ridout, the future surveyor-general of Upper Canada, was

captured on the Ohio by a group of Shawnee. Although suffering

considerable hardship while living in the Indian towns, Ridout observed,

upon being paroled at Detroit, that "it is almost needless to say to

those who are acquainted with the causes of disturbance between the

Americans and natives, that the former are in general the aggressors,

but in this war they are so in a more unjust degree than

usual."46

While atrocities were being exchanged on the frontier, St. Clair

waited patiently at Fort Harmar for the Indians to arrive. The tribes had

assembled at the Maumee in October, 1788, to discuss the feasibility of

treating with St. Clair. Some of the more remote western bands saw no

need for another treaty: their towns were too far removed to feel the

pressure of American expansion. Joseph Brant persisted, however, and

counseled a policy of moderation, suggesting that the Muskingum-Venango

line would provide a reasonable compromise to the Ohio River boundary.

The tribes were badly divided over this proposal, and the Shawnee and

Miami finally left the meeting in anger. Indian unity, the keystone to

successful native resistance against the Americans, was again rent. The

other tribes agreed to attend the St. Clair meeting, but Brant, his

dream of a united Indian nation apparently shattered, refused to be a

part of the separate tribal negotiations with the

governor.47

In January, 1789, a number of native bands, with the notable exception

of Brant's Mohawks and the militant Shawnee and Miami, gathered at Fort

Harmar on the Ohio River near Marietta. Initially the tribal delegates

pressed for the retention of the Ohio line, but St. Clair refused. After

considerable bickering the Indian leaders reluctantly agreed to

negotiate two separate and dictated treaties. On 9 January 1789, the Six

Nations, led by their pro-American Seneca orator Cornplanter, accepted

the terms of St. Clair which reaffirmed the boundary provisions

established by the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1784. But the Americans

made a notable concession in that they paid the Iroquois $3,000 for the

land ceded. Although the governor did not fully concede the Indian right

to the land of the Northwest, he did comply with the principle of

purchase.48 A second treaty was arranged with the Algonkian

Indians on the same day. Again the tribal leaders renewed the boundary

fixed by the Treaty of Fort Mcintosh. For this concession the Indians

received $6,000 in presents and goods.49

The treaties of Fort Harmar opened up the great part of the Ohio

valley to American occupation. St. Clair regarded the negotiations as a

great victory; but the treaties had stained the honour of the native

leaders and by the time they reached their wilderness towns, their mood

had grown to a seething desire for revenge. The irony of the situation

was that the United States, moving rapidly in 1789 toward a policy of

peace and absorption, was forced to wage a desperate five-year Indian

war for which the new republic had neither the means nor the desire.

IV

Notwithstanding the treaties of Fort Harmar concluded by Governor St.

Clair with the Iroquois and several of the Algonkian tribes, the

tranquility of the frontier settlements, now extending 400 miles along the

Ohio, had not been secured. The Shawnee, Miami and Wabash tribes, who

had refused to attend the Fort Harmar negotiations, were determined to

prevent all American settlements northwest of the Ohio River; the

Indians were despatching war pipes, and a deputation was sent to Detroit

to announce war and to demand ammunition.50 Joseph Brant,

still vainly attempting to gain positive assurance of British support in

an Indian-American war, desired to know if the western posts were to be

kept or handed over to the "Yankees" who were "Taking advantage all the

time and the English appear to be getting tired of

them."51

The continual ravaging of white settlements in Kentucky and along the

Ohio prompted a concerned George Washington to call out the militia of

Virginia and Pennsylvania for the protection of the frontiers against

the incursions of the hostile tribes. The president cautioned St. Clair

that war with the Indians ought to be avoided "by all means consistent

with the security of the frontier inhabitants, and the security of the

troops, and the national dignity."52 But if the Indians

persisted, a campaign would be necessary.

Dorchester, who was concerned for the safety of the upper Province of

Quebec, was naturally suspicious of the movements of the United States

in raising troops. The governor feared that the purpose of the American

force was to subdue the Indians and then to attack the frontier

posts.53 But St. Clair, under instructions from Washington,

lessened British anxiety by informing the commander at Detroit that the

American expedition was designed solely for the purpose of "humbling and

chastising some of the savage tribes whose depredations are becoming

intolerable, and whose cruelties of late become an

outrage."54

The commander of the American expeditionary force was Brigadier

General Josiah Harmar, the senior active military officer of the United

States in the Ohio Territory. His army began to muster at Fort

Washington (Cincinnati) in September, 1790, but supplies were low and

the militia quotas of Kentucky and Pennsylvania were

incomplete.55 In spite of these vexing problems Harmar

marched for the Indian country in early October. The point of attack was

a group of Miami towns clustered about the portage between the Maumee,

St. Joseph and Wabash rivers. Harmar's advance met little opposition,

for the Indians burned their houses and cornfields and retreated ahead

of him.

Five of the largest Miami towns had been burned and 20,000 bushels of

corn destroyed, but barely a shot had been exchanged. Harmar was

satisfied; he had successfully completed his mission of destroying the

Indian settlements. Colonel John Harden, however, was disappointed at

the lack of action and received permission to make a reconnaissance in

force in the hopes of forcing an engagement with the natives. In two

separate battles on 20 and 23 October 1790, Harden was attacked and his

troops badly mauled by Shawnee, Miami and Potawatomi under the Miami

leader Little Turtle. In the first action the Americans suffered 300

killed, and in the second confrontation the Indians drove the Americans

into a swamp and killed 200 more, all, according to Elliott, with spear

and tomahawk. The number of Indians killed was only 25. American

prisoners professed that Detroit was the intended object in the

spring.56 After these engagements, General Harmar returned to

Fort Washington and St. Clair reported with incredible optimism that

"General Harmar has made a very successful campaign," but Washington was

disgusted with Harmar's results and wrote privately to the Secretary of

War; "I expected little from the moment I heard he was a

drunkard."57

12 Joseph Brass (1742-1807), the warrior. Painted by George Romney.

Inscribed lower right, Thayeadanegea.

(National Gallery of Canada.)

|

When the news of the disastrous campaign of General Harmar reached

Congress, that body immediately voted to augment the size of the

permanent military establishment. Major General Arthur St. Clair was

appointed commander-in-chief as well as governor. The concluding remarks

on the Harmar campaign were presented to Congress in a report by Henry

Knox who commented caustically that the army, at a cost of $320,000 had

burned some grain, destroyed a few bark huts and suffered over 200

killed, while Indian losses were less than 100.58

In November Little Turtle and Blue Jacket, a principal warrior of the

Shawnee, travelled to Detroit to ask the British for clothing and food

for the distressed Indian families who had lost everything during their

flight from Harmar. These two chiefs stated that war resulted because of

American encroachments on lands beyond the Ohio, and the tribes were

bound to defend their traditional hunting territories. The land, they

claimed, had always belonged to the Indians, and by former treaties the

Ohio was always considered the boundary line; this was rigidly adhered

to by the tribes.59

Emboldened by their success, the Indians made more frequent their

depredations, and the conditions on the frontier were now more

deplorable than before the American expedition. In January of 1791, native

bands destroyed the New England settlement of Big Bottom near Marietta,

and an attack was launched against Dunlop's Station near Cincinnati.

Several communities were entirely disrupted as murder, torture and

captivity became common.60

In the spring a number of tribes gathered at the Miami with the

intention of achieving an acceptable decision which would facilitate a

favourable termination of their troubles with the United States; but

Indian optimism, owing to their late victory, war preparations and

continual hostilities on both sides had widened the breach and peaceful

negotiations for the moment were not feasible.61 Grenville at

the Home Department was alarmed at the reports of Indian outrages and

urged Dorchester to effect a reconciliation of differences and establish

an atmosphere of peace in the western country. Dorchester was in fact

pursuing a policy which suited exactly the desires of the British Home

Department. In February of 1791 the governor told Sir John Johnson that

he would feel great satisfaction in being instrumental in putting an end

to the hostilities between the United States and western Indians. He

instructed Johnson to "learn the nature and extent of the specific terms

on which the Confederated Indian Nations would be disposed to establish

a great tranquillity and friendship with the United

States."62 The idea of open British interference in an

Indian-American war was clearly not sanctioned.

V

In 1791, the United States, despite overburdening financial

difficulties, was determined to conduct a second punitive expedition

against the Indians in an effort to bring peace and security to the

Northwest frontier. In April, St. Clair, after consultations with

Washington and Knox, returned to the Ohio country to undertake the

organization of his campaign. At Pittsburgh, the governor invited

Iroquois bands to join his force against the Algonkian

tribes.63 Ironically Congress, at the same time, had directed

Colonel John Procter of the American Indian Department to engage the

assistance of Cornplanter and other chiefs of the Six Nations in

peacefully settling the disputes between the Americans and the hostile

Ohio Indians.64 Owing to the influence, however, of Joseph

Brant, Alexander McKee and other members of the British Indian

Department, the Iroquois were persuaded to reject the American

proposals. In addition, Procter, who had hoped to meet with the natives

at Sandusky, was denied permission to proceed westward by Colonel

Gordon, the British commander at Fort Niagara. Gordon was angry because

the different American commissioners had avoided applying for British

aid, preferring instead to impress the Indians with their own

importance. The commander was convinced that if the Americans had

applied to the British government to bring about a peace on equitable

terms, "the results would have been accomplished long

ago."65 The American peace mission was thus abruptly

terminated, and Procter returned to St. Clair's base at Fort

Washington.

Throughout the summer and autumn, military preparations and active

hostilities were carried on by the Indians and Americans. The Shawnee

and Miami in particular were most hostile, raiding the back settlements

and attacking flatboats along the Ohio River.66 Toward the

end of May an American army of 700 under the command of Brigadier

General Charles Scott marched against the Upper Wabash tribes and

destroyed a few towns belonging to the nonbelligerent Wea and

Piankashaw. The militia killed a number of old men, women and children left

behind, and to the apparent horror of Alexander McKee, the Americans

skinned a chief whom they had killed.67 In July, Brigadier

General James Wilkinson led an expedition of 500 Kentucky militia

against several more distant Wabash towns. This force met no opposition,

but succeeded in burning some villages and killing a few

natives.68 These raids only heightened Indian-American

contempt and bitterness, and the desire for retaliation was mutual.

Indian councils were held in early July at the foot of the Miami

rapids.69 The chiefs were determined to form a confederacy of

all the tribes to defend their country to the last and the boundary they

contended for was the Ohio River. At the same time, St. Clair was

grappling with the difficulties of raising troops in the frontier. His

force was ill-equipped and untrained; the lash was applied liberally,

desertion common, murder not unknown, and the problem of logistics ever

plaguing.70 Yet in spite of these mounting perplexities St.

Clair marched for the Indian country in September. His force constructed

two posts called Fort Hamilton and Fort Jefferson in mid-October in order

to protect the lines of communication.

13 Sir Frederick Haldimand (1716-91), governor general of Canada.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

The Indians, commanded by Little Turtle, had been supplied from the

British stores at Detroit. To further bolster native confidence,

Alexander McKee, Matthew Elliott and Simon Girty and other notables of

the British Indian Department were present to act as advisers. Girty

noted that "the Indians were never in better heart and are determined to

drive the Americans to the Ohio and to starve their posts."71

St. Clair suffering from a severe case of gout, advanced cautiously

through the wilderness, heeding the words of Washington, "beware of

surprise."

At sunrise on 4 November 1791, the Indians assaulted the American

camp. The militia panicked almost Immediately, but the regulars held

their ranks and managed to check the ferocity of the native thrust;

however, the death of Richard Butler, the second in command.

disheartened the Americans who began to give way and finally fell into

utter confusion.72 The fugitives, throwing away arms and

equipment, continued their flight for 30 miles until they reached Fort

Jefferson. The battle was one of the most severe ever fought between Indians

and Americans. Casualty figures have been hotly debated: Americans

losses range from 500 to 1,500; native losses from 50 to 150. But

unquestionably, the affair was the greatest Indian victory since the

Braddock disaster of 1755. In an anonymous letter from Niagara, the

details and implications of the battle were clearly outlined.

The American Army of which no doubt you have this summer heard,

had advanc'd on the third of this month to within Forty Miles of the

Miamis Towns, they were there encountered by near Two thousand Indians,

who on that day took from them the greatest part of their Horses &

Cattle — On the 4th, at Sun rise they attack'd their Camp, but Were

twice repuls'd, irritated beyond measure, they retir'd to a little

distance, where separating into their different tribes and each

conducted by their own Leaders, they returned like Furies to the assault

& almost instantly got possession of near half the Camp — they

found in it a row of Flour Bags, & bags of Stores, which serv'd them

as a Breast work, from behind which they kept up a constant & heavy

fire, the Americans charg'd them several times with Fixed Bayonets, but

were as often repuls'd — at length General Butler, second in

Command, being kill'd, the Americans fell into confusion & were

driven from their Cannon, round which a Hundred of their bravest Men

fell, the Rout now became universal, & in the utmost disorder, the

Indians follow'd for Six Miles, & many fell Victims to their Fury,

in the Camp they found 5 pieces Brass Cannon, 3 of 6 & 2 of 4

pounds, 1 4-1/2 Mortar & 2 paturaros, all Brass & mounted for

field Service, with these they took all the Arms, Ammunition,

Provisions, Cloathing, entrenching Tools, and Stores of every kind, the

Americans had in their Camp for the purpose of erecting Forts, &

remaining the ensuing Winter in the Indian Country, besides the

Commanding Officer, the Adjt. Genl. & Surgeon Genl. Twelve hundred

are said to have Fallen in the Assaults & pursuits—you however

know the Indians, most probably this Number is exaggerated we do not

hear of one prisoner — about 50 of the Indians are said to be

killed & wounded, the Numbers at first were American Regulars 1500,

Militia 800, in all 2300 — of Indians nearly 2,000. Two Forts they

had erected on their Rout nam'd Hamilton & Jefferson, are said to be

surrounded by the Indians, they contain 100 Men each with but little

provisions; the truth of this information may be depended on, Simon

Girty, if not in the action, was within view of it. He had join'd

Coll. McGee at the foot of the Rapids brought the American Orderly

Books & all their papers—Butler's Scalp was brought in, &

is sent they say to Joseph Brant with a severe Sarcasm for his not being

there — He is at the grand River with the Six Nations —

Cowan in the Felicity was dispatch'd with the interesting intelligence.

I saw him yesterday at Fort Erie — He left your Brother well on the

14th who had sometime before hurt his arm and was not yet able to write,

an Express is now getting ready for Quebec, finding an opportunity I

send this by New york. Humanity shudders at the number of poor wretches

who have fallen in this Business, but as they were clearly the

agressors, they merit less pity, the horrible Cruelties that may

probably now fall on the defenceless Frontiers of the Western American

Settlements, is infinitely more dreadful & claims from every

person who can feel as a man, every preventative that can be devis'd; I

have this morning wrote to our Friend Mr. Askin strongly pressing him

to join the Trade in inspiring the Indians with moderation. The

Americans must be severely hurt at this Blow, however willing to resent

it, they will find great difficulty in raising another Army for this

Service. They would probably listen to any Reasonable Terms of

accommodation, if they saw a prospect of its being establish'd on solid

Grounds, perhaps this can only be affected by the influence of the

British Government & Trade with the Indians — The Terms the

Indians ask'd were, that the Ohio shou'd be establish'd as the Boundary

to the American Settlements, & that they shou'd enjoy unmolested

their hunting Grounds, to the West & North of that River, some of

the Branches of the Ohio to the Southward of this come within a few

Miles of the Genesea River, which runs into Lake Ontario Sixty Miles

East from the Fort of Niagara — If these two Rivers by the

interposition of Government cou'd be fix'd as the Boundaries between the

Americans and Indians, & between them & us, we shou'd secure our

Posts, the Trade, & the Tranquility of the Country; you will know

that the present lines must furnish a source of constant Contention

& dispute— The others now propos'd being on Streams not

navigable, will be free from this, the Indians not having as yet sold

their Country between this & the Genesea nor does any of the

American Settlements extend to the West of that River, but they very

soon will—I wish our Peacemakers of 83 had but known a little more

of this Country. I wish our present Ministry were informed of the actual

situation — perhaps this is the important moment in which the

unfortunate terms of that Peace maybe alter'd — Perhaps this moment

may never return —

A month after the battle Alexander McKee wrote his superior, Sir John

Johnson, giving him details of the St. Clair campaign. The agent noted

that a minor chief, Quania, and ten men were the only Six Nation Indians

who took part in the fight.73 Joseph Brant, to the derision

of the western tribes, did not participate. The Mohawk leader was

convinced that a compromise boundary line was the only solution to an

Indian-American peace, and war would only hasten the death of native

life and culture in the Ohio valley. The opinion of this influential

Iroquois was to have a profound effect on the future status and

negotiations of the Indian confederacy.

Along with the Indian warriors who participated in the battle against

St. Clair was a considerable number of Canadians and mixed bloods.

Traveller Isaac Weld commented that

A great many young Canadians, and in particular many that were

born of Indian women, fought on the side of the Indians in this action,

a circumstance which confirmed the people of the States in the opinion

they had previously formed, that the Indians were encouraged and abetted

in their attacks upon them by the British. I can safely affirm, however,

from having conversed with many of these young men who fought against

St. Clair, that it was with the utmost secrecy they left their homes to

join the Indians, fearful lest the government should censure their

conduct.74

The struggle for the Ohio valley was an Indian-American

confrontation. Many mixed bloods and refugee Americans, particularly

those who became members of the British Indian Department, actively

encouraged tribal resistance to American expansion. These men lived

among the native people, spoke their language, married their women,

fathered their children and attended their councils; thus they

maintained a considerable influence in policy-making. Vitally

significant also, they possessed the sine qua non for an Indian

war: the power to imply, promise, even hope for British assistance.

14 Sir John Johnson (1742-1830), superintendent general of Indian

affairs, 1782-1828.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Yet Whitehall, as represented by the new secretary of state of the

Home Department, Henry Dundas, was officially maintaining a policy of

the strictest neutrality. Dundas ordered Dorchester to

show every consistent mark of attention, in regard to the Indian

Nations who have showed proofs of attachments to the British

Interests [but] . . . every means which prudence can suggest

should be taken for healing the differences which at present exist

[between the Indians and Americans], and for effecting, if

possible, a speedy termination of the war. The chief object is to obtain

for the Indians the peaceful possession of their hunting

grounds.75

The Indians, revelling in the glory of a second successive victory,

ravaged the defenceless northwest frontier in the winter and spring of

1792. Although the Indian war had been provoked by reciprocal

depredations, Congress conceded that the whites were more probably the

aggressors, as they frequently made encroachments on tribal lands.

Indeed after the St. Clair battle, the Indians could have swept clean the

country before them as far as Pittsburgh, for there was not a

sufficient force to check their advance.76 But the Indians

were concerned solely with the defence and preservation of their natural

way of life within the confines of the land bordered by the Ohio River

and the Great Lakes, as agreed to by the Treaty of 1768.

Washington was most distressed at the inability of the army to remove

the Indian menace, but Congress was more accurate in assessing the

problem.

It is only exposing our arms to disgrace, betraying our own

weakness, and lessening the public confidence in the General Government, to

send forth armies to be butchered in the forests, while we suffer the

British to keep possession of the posts within our

territory.77

Undoubtedly the tribes would not be able to effectively continue

their operations against the Americans if the United States had the

western posts. The British gave the Indians supplies, clothing, food,

arms, ammunition and most of all, encouragement to persevere in their

efforts to maintain their Ohio valley home lands. Nonetheless, in spite

of British assistance in the Indian cause, it was "not the inclination

or interest of the United States to enter into a contest with Great

Britain."78

VI

The twin Indian victories in 1790 and 1791 presented Whitehall with

the opportunity to formulate a scheme for a native barrier state. The

plan as described to George Hammond, the first minister to the United

States, was to suggest British mediation between the Americans and the

Indians to create a separate country for the tribes, independent from

Great Britain and the United States; the boundary would be formed by

the Great Lakes and the Mississippi and Ohio rivers.79 Lord

Dorchester, on leave in England, fully supported the proposal.

If the area northwest of the Ohio between the Mississippi and the

Lakes shall be secured exclusively to the Indians, and remain neutral

ground in respect to Great Britain and the United States, peace between

them and the Indians will be restored immediately, and established upon

a solid foundation.80

The creation of an Indian buffer state was designed to protect Upper

Canada from the territorial ambitions of the American republic, preserve

the hunting grounds for the Indians who had been under British

protection and, of secondary importance, enable Canadian fur traders to

continue operating in the region south of the Great Lakes from which

they might otherwise be excluded.81 The price Britain would

have to pay was the surrender of the western posts. Nonetheless

Hammond, as instructed, merely suggested to Thomas Jefferson, Secretary

of State for the United States, the feasibility of establishing a

national home for the Indians in the Ohio valley. But the Americans

firmly rejected this offer and demanded that the British evacuate the

western posts "with all convenient speed," as stipulated in the 1783

treaty.82

The arrival of John Graves Simcoe as the first lieutenant governor of

Upper Canada in the summer of 1792 further strained Anglo-American

diplomatic relations. Simcoe had absorbed a violent antipathy to

everything American in the course of his active military career with the

Queen's Rangers during the Revolutionary War. He had accepted the

Canadian post in the hope of being instrumental in the "Reunion of the

Empire," and openly confessed that there was "no person who thinks less

of the Talents or Integrity of General Washington than I

do."83 The biggest fear of the lieutenant governor was that

the Indians, if left to make their own peace with the republic, would

then fall like a scourge upon a defenceless Upper Canada. What inspired

Simcoe, however, was the hope of strengthening and extending British

influence in the interior of the continent.84 His position

was precarious because the official policy of Whitehall, like that of

the United States, was to maintain an atmosphere of peace and

cordiality between the two countries.

While Great Britain and the United States debated over the possible

solutions to the native problems, Joseph Brant and a number of Iroquois

were becoming increasingly disenchanted with British promises and the

war against the Americans. Henry Knox had made peace overtures to the

Six Nations and Brant was tempted to negotiate. The Mohawk leader wrote

McKee that the British government gave only evasive answers.

If Great Britain wishes us to defend our Country, why not tell us

so in plain language . . . . There is now a field open for our

accommodation with the Americans . . . make them explain themselves on

this subject, which I have never as yet, been able to prevail upon them

to do.85

Discouraged by the vacillation of British native policy and realizing

that the Indian victories had provided the tribes with a degree of

bargaining power, Brant became convinced that the time was opportune to

attempt a restoration of peace with the Americans through negotiations.

To ensure that at least a part of the Ohio valley could be preserved for

Indian use, Brant was prepared to accept a compromise boundary line.

Many chiefs of the Six Nations supported the Mohawk's convictions, and

with this idea firmly established in their minds, the Iroquois accepted

an invitation to attend a large Indian conference in the summer of

1792.

The council at the Glaize, a tributary of the Miami River, was

called by the various tribal leaders to ascertain what military and

political strategy the Indians could agree upon in event of another

confrontation with the Americans. Alexander McKee, representing British

interests, was present at the assembly. Simcoe advised the agent that

he should encourage the Indians "to solicit the King's good offices;"

but fully aware of the pacific policy of Whitehall toward the United

States, the governor warned McKee that

This solicitation should be the result of their own Spontaneous

Reflections. [We] must assure our neutrality which we gave

Congress; there should appear on our part nothing like Collusion or any

active Interference to inspire them [the Indians] with such a

sentiment.86

The proceedings commenced on 30 September 1792. The delegated speaker

for the Algonkian tribes was Painted Pole, a Delaware, who directed his

speech toward the Six Nations, accusing them of scheming with the

Americans. Cowkiller, a noted Seneca orator, spoke for the shocked

Iroquois delegation. "You have talked to us a little too roughly, you

have thrown us on our backs."87 The Iroquois consulted in

private for about an hour and then returned to the council.

Surprisingly, the chiefs of the Six Nations reconciled their differences

with the Algonkian tribes and agreed that instead of a third successive

campaign, they would meet with the Americans at Sandusky the following

spring. The Six Nations were given the honour of carrying the word of

peace to the commissioners of the United States. However, the harsh

exchange of words and divided opinion had left a mutual feeling of

suspicion and doubt between the Algonkian tribes and Six Nations.

Although both groups had fully consented to the Ohio River as the only

negotiable boundary, the Iroquois, particularly the Seneca, were

greatly exposed to American settlement and military strength: thus this

important faction of the Six Nations was in a state of vacillation as to

whether the Ohio should be the boundary or whether, for their security,

a suitable compromise should not be obtained if the Americans pressed

for such.

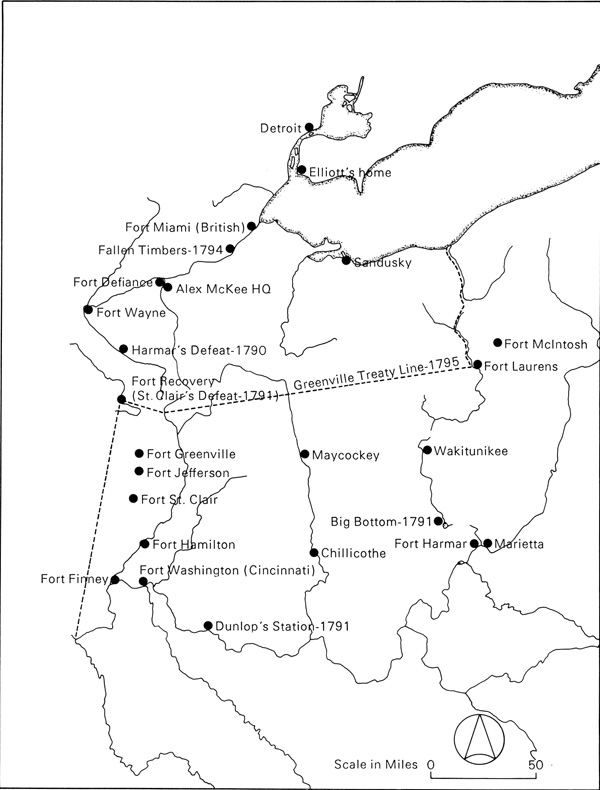

15 The Ohio country, 1783-96.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

Joseph Brant, suffering apparently from a "fit of sickness" did not

reach the Glaize until the end of October. The influence of the Mohawk

leader was important to the cohesive power of the Indian confederacy.

Those chiefs who were still present hastily assembled a rump council for

the dignitary. Brant was relentless in his theme of Indian unity as the

only method of safeguarding native culture in the Ohio valley. Those

chiefs present acknowledged his wisdom and assured their esteemed

visitor that tribal unity would be preserved.88

Representatives of the Six Nations travelled to Buffalo Creek in

November to meet the American commissioners and deliver the announcement

devised by the Indian confederacy at the Glaize conference.89

Although the Americans accepted the Sandusky peace proposal, a deadly triangle

had been formed. The Algonkian tribes led by the Shawnee, Miami and

Delaware were adamant in their determination to defend the Ohio River

boundary line. This group expected British aid in time of crisis, and

with two victories to their credit assumed an air of genuine confidence.

The Iroquois, who had adhered to the Ohio line in council, were

impressed with the rhetoric of Branton unity, but like Brant and in

spite of the promises to the contrary, they were prepared to accept the

compromise Muskingum-Venango line. The Americans, who were eager to

grasp at any straw that might result in peace, had agreed to the

Sandusky conference, but the commissioners were not content with the

Ohio boundary and hoped that a combination of presents and verbal

persuasion would induce the natives to accept a new line. The only

alternative for the tribal confederacy was the renewal of war and the

possibility of Indian collapse. The keystone to a successful Indian

resistance to American expansion was active British assistance. If

Britain would not aid the tribes, Indian supremacy in the Ohio valley

was doomed.

|

|

|

|