|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 9

The Canadian Lighthouse

by Edward F. Bush

The Great Lakes Region and the Upper St. Lawrence

Around the beach the sea gulls scream;

Their dismal notes prolong,

They're chanting forth a requiem,

A saddened funeral song.

They skim along the waters blue

And then aloft they soar

In memory of the sailing men

Lost off Lake Huron's shore!

(popular lake song composed on

the loss of the schooner Persia with all hands in

November, 1969)

In order to describe early developments on the Great Lakes, it is

necessary to return to the early years of the 19th century when the

Province of Upper Canada was very much of a backwoods wilderness.

Pioneer settlements existed at such places as York, Newark and Niagara,

with Kingston only presenting a finished aspect.

These vast freshwater inland seas, the Great Lakes, ravaged

frequently by savage storms, offered a challenge to the mariner

comparable to the ocean itself. Seas on the lakes were shorter and

sharper, and at the same time the navigator was ever within range of the

perils posed by off-shore navigation — rocks, shoals and sandbars.

Lighthouses, therefore, were as much a necessity to the Great Lakes

mariner as to his contemporary on the high seas. And, in fact,

lighthouse development on Lake Ontario was coincident with that on the

lower St. Lawrence as well as with many of the early installations on

the Atlantic coast.

In a more or less chronological account of early lighthouse

construction on the Great Lakes, the trend of settlement will be

followed, from Lake Ontario, over the steep Niagara escarpment to the

shallow reaches of Lake Erie, thence through Lake St. Clair to the

broader expanse of Lake Huron, and finally to the frigid, rock-bound

waters of Lake Superior, more than 600 feet above sea level. (Lake

Michigan, lying wholly within American territory, is not included in

this treatment.) With the first settlements and resultant waterborne

trade, safeguards to navigation soon followed.

Lake Ontario

The journals of the House of Assembly for Upper Canada record the

passing of an Act dated 5 March 1803 "to establish a fund for the

erection and maintaining of lighthouses."1 Lighthouse

commissioners were appointed who were directly responsible to the

governor; later, in 1833, the inspector general took over this

responsibility.2 With the Act of Union in 1841, lighthouses

and divers aids to navigation came under the jurisdiction of the

Department of Public Works, although until Confederation, those below

Montreal remained the charge of the Montreal and Quebec Trinity

Houses.

Mississauga Point

The first lighthouse to grace the shores of Lake Ontario was built at

Mississauga Point at the mouth of the turbulent Niagara River, a site

recommended by the Board of Lighthouse Commissioners on 17 April

1804,3 James Green, the Niagara customs collector, was given

charge of the work and the contractor was a John Symington. When the

project was completed, the officer commanding at Fort George was to

appoint "a careful non-commissioned officer or soldier to keep the

lights lighted during the season for which he will receive from the

commissary at the post one shilling Halifax currency per

day."4 Military masons of the 49th Regiment of Foot were

engaged at civilian rates. The resultant labour cost became the subject

of official correspondence in which an ambitious young officer,

Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Brock, found it advisable to render his

superiors an explanation, dated 15 November 1804.

To the statements

therein given I verily subscribe requesting at the same time to be

allowed to add that, in giving my consent to the masons of the 49th.

Regiment assisting in building the Lighthouse at Mississauga point, I

had no idea they would be employed longer than two or three days, as

they were then under orders to proceed to Amherstburg in the

Canadian, which was momentarily expected, but her arrival having been

delayed a fortnight or three weeks, beyond his usual time, they were in

consequence, enabled to finish the building. I embarked soon after

giving my consent, for Kingston, without once supposing it possible the

masons would have time to earn so many dollars.5

It transpired that the resultant cost, using military labour, ran to

£9 7s. 6d. The total outlay came to £178 3s. 8d. Halifax

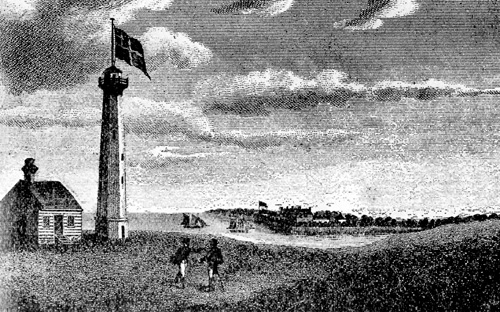

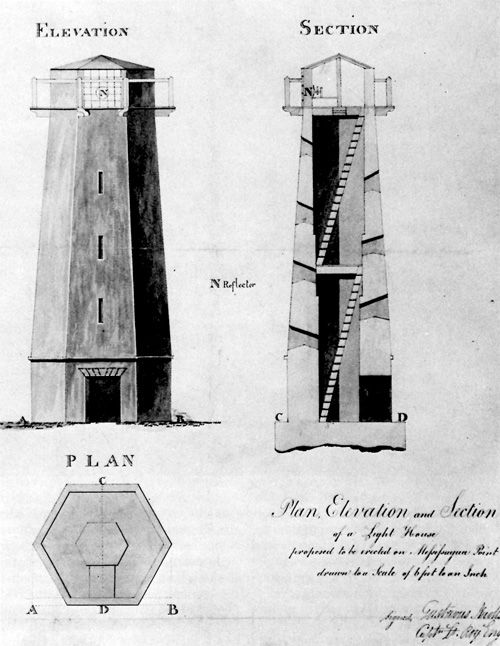

currency.6 The hexagonal tower, an artist's attractive sketch

of which appears in Figure 53, was completed in 1804 preceding by five

years Green Island lighthouse, the first on the lower St. Lawrence.

Research to date has not elucidated the type of apparatus used on this

first lighthouse on the Great Lakes; the light may have been derived

from tallow candles, or more likely from one or more Argand lamps fitted

with reflectors and burning sperm oil. In any case, the Mississauga

lighthouse stood for only 10 years, giving place to fortifications in

1814 following the American sack of Niagara.

53 Drawing of Mississauga lighthouse, the first on the Great Lakes.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

54 Plan and profile of the Mississauga Point lighthouse 1804.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

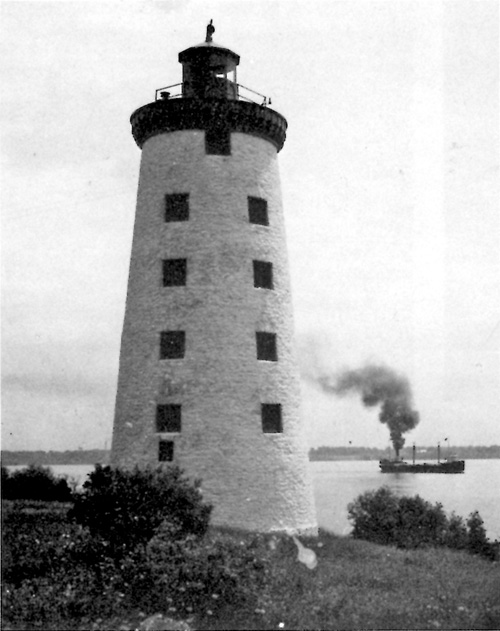

Gibraltar Point

Authorization for the construction of the Gibraltar Point lighthouse

on the crescent-shaped island enclosing what was to be one day the busy

port of Toronto was given on 1 May 1808, the project to be directed by

William Allan whose commission read:

You are hereby authorized and directed to provide such materials

as may be required for the purpose of erecting a Light House on

Gibraltar Point, under the authority of an Act passed in the Third

Session of the Third Parliament of this Province, and also to pay the

workmen employed thereon.7

Constructed solidly of limestone by artificers of the 41st Regiment,

the tower was originally built to a height of approximately 67 feet,

with a 15-foot extension added in 1832. The hexagonal tower, as may be

readily seen in Figure 56, has vertical sides for the first 10 feet or

so, after which the walls assume a slight taper up to the extension, of

slightly different stonework, which again assumes the vertical. The

tower door, recessed slightly into the four-foot-thick wall, has a

pleasing rounded arch. The original lock is in place, to be opened by

means of an enormous, outsize key. The polygonal lantern and platform

are not the originals, being of a design more frequently seen in the

later 19th century. The lantern deck was sheathed with copper as a

precaution against fire.8 The lantern is gained by a spiral

staircase. in the centre of which rises the original weight shaft, a

revolving light replacing the former fixed one in 1832.

Figure 55 depicts the Gibraltar Point lighthouse as it appeared in

the early days of "muddy York," and Figure 56 as it stands today in

quiet, spacious and well-tended parkland, across the bay from the

maelstrom of downtown Toronto.

55 Sketch of the Gibraltar Point lighthouse as it

once was. This is the second oldest lighthouse extant in Canada, located

on Toronto Island. It is no longer in use but is preserved by the city

in excellent condition.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

56 Gibraltar Point lighthouse, as it is today.

(Photo by author's son.)

|

Leaking lanterns have always been a problem with lighthouses, and

Gibraltar Point was no exception. By 1822, the lantern stood in obvious

need of repair, the rain beating in to such a degree that frequently the

light was extinguished. In the words of its builder, William Allan,

reporting to the executive council that year,

The roof leaks so much that whenever there is any Rain, with the

least Wind, it heated in all round it so much that the Lamps are

frequently extinguished and it is not possible to keep the lights in

during any Storms which generally

happens at Night. The Wet is also gradually rotting the Floors above

and the Stairs... I don't think the expense can exceed £15 or

£20.9

"Haunted" lighthouses are most likely as common as allegedly

ghost-ridden old houses. Apparently the first keeper of the Gibraltar

Point light died suddenly in 1815 under mysterious circumstances; the

subsequent discovery of a human skeleton near the site gave rise to the

legend that the lighthouse was haunted.

The Gibraltar Point lighthouse is the oldest extant in the Great

Lakes region and second only to Sambro Island in the whole of

Canada.

False Ducks Island

Lighthouse construction in Upper Canada proceeded

slowly in these early years. The establishment of a Trinity House for

the region, suggested by Lord Bathurst in 1816, was never

implemented.10 In its session of 1832-33, the legislature

observed that to date, besides the Gibraltar Point light, only two

additional lighthouses had been built in the area — Long Point on

Lake Erie and False Ducks Island at the eastern end of Lake

Ontario.11

The latter, an early installation built in May 1828, was quite

recently demolished. J. W. Macaulay, lighthouse commissioner, complained

of "the scantiness of the appropriation" and the lack of suitable sand

and stone on the site. Nonetheless the commissioners addressed

themselves to their task.

We have an idea of building a round tower, nearly in the

proportion of a Tuscan column, and as small in its diameter as may be

consistent with its solidity, in order to save

materials.12

In June 1828, Macaulay was able to report the making of "a very

advantageous contract" for a 60-foot stone tower with stairs and lantern

platform for the modest sum of £546.13 The lighthouse

was fitted with a polygonal lantern, and its four-foot-thick rubble

masonry walls were in fair condition nearly a century later. The

district engineer in 1924 recommended "the scabbling of the entire

surface," repointing with the best quality mortar, and the entire tower

to be whitewashed, the results of which may be

seen in Figure 5714 This lighthouse, unlike some of its

contemporaries in these early years, maintained a high reputation for

the quality of its light, apparently derived from three Argand lamps

with reflectors which in the words of the inspector general "are kept in

a more cleanly state than any which are to be found on the opposite

shores of Lake Ontario."15

57 False Ducks Island lighthouse, Lake Ontario, before renovation.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Point Petre

The Point Petre lighthouse was built under contract by the firm of

Matthews and Scott for the sum of £398. Located on the southwest

extremity of Prince Edward Peninsula, the Point Petre lighthouse, no

longer in use, stands about 12 miles from Picton. The 62-foot circular

and slightly tapered tower of "even coursed rubble" was "topped by a

cornice of stepped corbelling," on which was set the 12-sided lantern on

a platform of the same configuration. Neither the lantern nor the

platform is original.16 The original lantern was supplied by

a blacksmith, Thomas Masson, for £164 10s., and the chandelier,

reflectors, lamps and lantern glazing were ordered from Boston. The

commissioners were well pleased with the work.

The Commissioners have indeed great satisfaction in speaking

favourably of the work of the Contractors, who are most respectable

persons, and have performed their engagements in a very creditable

manner. The tower is built

in the most substantial manner, and cannot fail to endure for ages. The

frame work of the Lantern fits together with uncommon neatness, and is

secured in every respect better than any other Lantern that the

Commission has seen.17

The commissioners considered the Point Petre tower to be of sounder

construction than that at False Ducks. The light consisted of 11 Argand

lamps with 16-inch reflectors set in an iron chandelier and complemented

with 11 copper oil heaters, the whole supplied by Winslow Lewis of

Boston for the sum of $522.65.18 The Point Petre light was

said to have a range of 25 miles in clear weather.

Nine Mile Point

The Nine Mile Point lighthouse located on the western point of Simcoe

Island, a landfall light for vessels making for the St. Lawrence from

Lake Ontario, is of identical design to the Point Petre structure but

only 45 feet in height. The Nine Mile Point lighthouse is still in use

today. The old weight shaft and weights are still in place, though the

lantern is thought to have been replaced at a later date. This

lighthouse is one of the few, other than range lights, equipped with the

reflector or catoptric type light, the apparatus consisting of three

parabolic copper reflectors lined with quicksilver. Built in 1833 it is

not surprising that the mortar is now soft, and so this tower may

require considerable maintenance to preserve it. The site is accessible

to motor by means of two ferries.

Presqu'lle

Another important lighthouse, built in 1840 in the eastern waters of

Lake Ontario and still in use today, is that of Presqu'lle. Located

three miles from Brighton, the Presqu'lle lighthouse is an octagonal

stone structure, shingled throughout on the exterior and set on a stone

base cemented over at a more recent date.19 The cornice, as

indicated in Figure 58, exhibits a pronounced flare noticeable from the

ground. There are five landings within connected by steep straight runs

of stairs with an almost ladder-like ascent. Originally the lighthouse

was fitted with a polygonal lantern with guard rail around the

observation platform. but recently the lantern has been replaced with a

rotating beacon mounted on a buoy structure. The Gothic arch of the door

is of rather an ecclesiastical outline.

58 Presqu'lle lighthouse, Lake Ontario, as it is today. The lantern has

been removed and a rotating airport beacon installed directly on the

lantern platform.

(Photo by author's son.)

|

Burlington

At Burlington, located at the western extremity of Lake Ontario, two

lighthouses were built at an early date, the first in 1838; this one is

still standing, although removed from service in 1961. Overtaken by

highway construction in recent years, the old Burlington light, situated

on a canal known as the Burlington Cut by which shipping enters the bay

from the lake, found itself overshadowed by the Burlington Skyway and

cheek-by-jowl with a lift bridge. The present light is shown from a

reinforced concrete tower, complete with a radio beacon and Airchine fog

alarm on the end of the jetty. The old lighthouse, as may be seen in

Figure 59, is a tall graceful structure in stone, the tapering tower

rising to a height of approximately 55 feet20 with narrow

rectangular windows at each of the four landings giving ample evidence

of the thickness of the walls. The lantern is believed to be of more

recent date. The department had decided upon its demolition, since in

this location the light was manifestly useless. Strenuous protests from

a local historical society have to date, however, saved the old

structure from the wrecker's hammer.

59 Burlington lighthouse, no longer in service.

(Canada. Department of Transport)

|

Queen's Wharf

A curious but pleasing survival from Toronto's early days is the

diminutive Queen's Wharf lighthouse, whose construction date in the 1864

Admiralty list of lights is cited as 1838 and as 1861 according to the

Toronto Historical Society. It is a square frame, two-storey structure

with angles at each corner sheared off. It has widely

projecting eaves, and its height, base to vane, is not over 20 feet.

This little lighthouse was moved about 500 yards from its original

location on Queen's Wharf when the city under took a large-scale

reclamation of land along the waterfront in 1911; its present position

within a street car loop is at the intersection of Fleet Street and

Lakeshore Boulevard, a good distance from the harbour. The light has not

been in use since this time but the well-built little structure has been

kept in excellent condition by the Toronto Historical Society. The only

renovation has been the replacement of some of the sheathing boards and

the exterior siding, although the original style has been faithfully

maintained.21

60 The Queen's Wharf lighthouse, Toronto. Moved from its original

location, it is so longer in service.

(Photo by author's son.)

|

Port Dalhousie

Port Dalhousie Harbour on the south shore of Lake Ontario features

two fairly old frame range lights. The main light, built in 1879, is of

the common, square tapered design with an octagonal lantern. The doorway

on the south side projects from the wall and has an attractive gabled

roof, more or less creating a porch effect, with a transom above the

door. John R. Stevens, architect, reported this old range light to be in

good condition.22

The inner range light at Port Dalhousie, built in 1852, consists of a

four-storeyed octagonal tower with a 12-sided lantern. The gently

tapered walls are shingled. Stevens doubts that this lighthouse dated

from 1852, considering that its general configuration and design are

attributable to the 1870s rather than mid-century.23

Lake Erie

Long Point

Moving over the Niagara escarpment to the shallow waters of Lake

Erie, one finds an obvious place for the first lighthouse to grace its

shores at Long Point, a sand spit running at an oblique angle some 20

miles out into the lake. As early as 1817, the lieutenant governor of

the province cited the need of a lighthouse at this point. The

completion of the Welland Canal in 1829 gave added impetus to the

project, as a landfall for shipping making for the canal entrance.

The shallow waters of Lake Erie were frequently whipped to fury by

sudden and violent storms. Long Point, judging from American

representations to the British minister in Washington, was the scene of

many mishaps.

The navigating and commercial interests on Lake Erie sustain

serious losses from the want of a Lighthouse on Long Point, in Upper

Canada. This point stretches so far into the Lake that in violent storms

vessels are unavoidably driven on to it in the night, and not only

property, but the lives of mariners are lost. I understood last fall,

that four of our vessels were driven onto this point in one storm; that

a part of them went to pieces, and that the hands on board those wrecked

perished.24

The gist of the matter reached the Foreign Office and eventually

Government House. In March 1829, the sum of £1,000 was

appropriated for the project, undertaken by Joseph Van Norman and

Brothers who contracted to build the lighthouse equipped with lighting

apparatus for £925 local currency.

61 Former lighthouse near Long Point Bay, Lake Erie, now used as summer

cottage.

(Photo by author's son.)

|

The first in a series of three lighthouses on Long Point went into

service on 3 November 1830. A circular stone tower 50 feet in height

whose walls tapered from a thickness of five feet at the base to two at

the top, was set on a seemingly solid foundation 30 feet square, made up

of two tiers of squared oak and pine.25 The care so taken,

however, was not proof against the continual erosion, which by 1838 had

thoroughly undermined the structure. The inherent difficulties of the

site were expressed by G. Ryerse, customs collector at Port Dover, who

undertook the rebuilding of the lighthouse for the sum of $1,212, in a

letter to the inspector general on 22 February 1839.

Agreeable to your request I lay before you the state of the

light house on Long Point. I suppose you are aware that . . . concerning the

precarious state in which the lighthouse was situated almost the whole

time surrounded with water, partly undermined, entirely useless in

stormy times, being unapproachable, and almost certain of falling in the

lake in the spring, it being impossible to protect it with piles, it

being founded on deep moveable sand, at the edge of deep water, the

beach having disappeared and the water becoming deep for more than

eighty yards after it was built.26

The second Long Point lighthouse was begun on 10 April 1843 and

completed ready for service on 16 September of that year. The structure

was an octagonal wooden tower 60 feet in height, and the original light

was a fixed one employing 16 Argand lamps. The lamps were later reduced

to six on the revolving principle and fitted with silver-plated copper

reflectors.27 To complete the story of Long Point, one may

mention that the third in the succession of lighthouses, a reinforced

concrete tower 102 feet high, went into service in May 1916, and is

still in use at the present time.28

But before leaving Long Point, now a popular summer resort, one

should note yet a fourth lighthouse built in 1879 on the neck of land

separating the lake from Long Point Bay (Fig. 61). The square tower with

attached dwelling is of frame construction plastered on the inside and

shingled on the exterior. The tower has two landings leading to what is

now a sunroom, for the light was removed from service sometime between

1915 and 1920 and the structure has since served as a residence. The

verandah and kitchen are additions to the original structure. The lantern has

been removed and, it is surmised, replaced with the sunroom. At present

this one time lighthouse serves as an outsize summer cottage which can

accommodate comfortably several families at a time.

Pelee Island

The second lighthouse to be built on the Canadian shore of Lake Frie

was that on the northeast point of Pelee Island. Built in 1833 and

situated in the hazardous Pelee Passage by which shipping passed in

increasing tonnage to the upper lakes, the Pelee Island lighthouse

exhibited a fixed light for which a range of 9 miles was claimed.

The round stone tower was 40 feet in height.29 Despite the

importance of this light to navigation, the early one was neglected. The

light was destroyed by the rebels in 1837 and was not

relit the following spring. A complaint on the neglected state of the

Pelee Island light appeared in official correspondence that summer. "The

want of attention to the Lights upon this shore is a source of complaint

among our traders, as they still pay the dues without reaping the

benefit."30 The following year the quality of the light was

still unsatisfactory, the result of negligence on the part of an

absentee keeper. By 1845, however, the Board of Works had secured the

services of a conscientious keeper, a retired German

sailor.31

62 Plan of Point Pelee lighthouse, 1858.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Despite the manifest improvement in the Pelee Island light by this

date, it had become apparent that a much stronger one was required to

keep shipping clear of the dangerous shoal. The poor condition of the

foundation precluded modifications to the present tower. J. Mcintyre's

Report on Lighthouses for 1845 stressed the pressing need for an

improved facility in this critical passage:

This Channel is becoming of more importance every year; all

vessels take it that are bound for the Upper Lakes. To make it navigable

at all times a revolving light would be required on the outer end of

Pointe aux Pelee not less than 70 feet high. . . .

The improvement of the Channel is of the greatest importance and I

would beg to call the attention of the Board to it, at as early a day as

possible.32

Only in 1861, however, was a considerably improved lighthouse

established on Pelee Spit, the foundation for which was a stone-filled

caisson well offshore. The 61-foot wooden tower was constructed on shore

and transported to the site. On 3 November 1861, the new coal-oil light,

made up of nine flat-wick lamps and six reflectors, went into

service.33 In 1902 a new cone-shaped lighthouse was

constructed of steel plates set upon a steel caisson filled with

concrete and masonry. This structure exhibited a powerful dioptric light

of the 3rd Order for the first time on 4 July. The establishment

included a steam fog siren, indicative of the importance of this light

station in the Pelee Passage.34

River Thames

Before proceeding to the upper lakes, we should mention a curiously

shaped lighthouse built in 1845 where the meandering Thames empties into

Lake St. Clair. The original coursed rubble tower was circular in shape

and had a slight taper; it was heightened considerably at a later date.

The tower is in very poor shape having developed an inclination, and the

masonry is disintegrating; the whole structure indeed is due for

demolition.35 This old lighthouse forms one of a pair of

range lights designed to guide vessels on a safe course over a dangerous

sandbar. Its companion, built in 1837, has been replaced recently by a

steel tower visible in the right background of the photograph in Figure

63. Although local representations have been made for its preservation

on historical grounds, by all accounts the old lighthouse is beyond

restoration.

63 River Thames range light.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Lake Huron

Goderich

The first lighthouse to be built on the shores of Lake Huron in 1847,

the Goderich lighthouse, stands on a cliff over 100 feet above the lake

level. Standing in what is now a park, this square and rather squat

stone tower faced with smooth, even-coursed stone still serves, with its

mercury vapour light, as a principal beacon along Huron's shore. In

1896, the original stone lantern deck was replaced with a reinforced

concrete slab; the lantern too is new.36

64 Goderich lighthouse, the first on Lake Huron, 1947.

(Photo by author's son.)

|

Imperial Towers

In 1859, the Department of Public Works completed a series of six

very tall tapering lighthouses of graceful proportions on the shores of

Lake Huron and contiguous Georgian Bay. These circular stone towers, all

of which have lasted well to the present day, are known locally and

within the department as "imperial towers." The derivation of this term

has not been traced. Certainly all were built under Canadian authority.

It may have been that the design originated in England, and local lore

in several instances traces the building material to Britain, but this

seems highly unlikely. Dwellings, storage sheds and out-buildings of the

same material originally formed one complex at each of these locations,

but at several sites only the lighthouse remains. The six lighthouses

are Point Clark and Chantry Island on the eastern shore of Lake Huron;

Cove Island off Tobermory at the entrance to Georgian Bay; Griffith

Island at the entrance to Owen Sound, and Nottawasaga and Christian

Island in southern Georgian Bay.

65 Point Clark lighthouse.

(Photo by author's son.)

|

With the exception of the Christian Island lighthouse which is but 60

feet in height, the other five towers all exceed 85 feet. All six are

fitted with red cast-iron polygonal lanterns, and the towers are

whitewashed. The powerful 2d Order light at Nottawasaga Island has been

replaced in recent years with an acetylene AGA-type beacon fitted into

the original optic; the light produced is a feeble one compared with its

predecessor. Apparently a light of such brilliance is no longer required

at the entrance to Collingwood Harbour.

The most southerly of the series, at Point Clark about 20 miles to

the north of Goderich, is situated on a low-lying shore and was so

located to warn mariners off a dangerous shoal about two miles offshore.

The Point Clark tower, containing nine storeys or

landings leading to the lantern, has tapering limestone walls fully 5

feet thick at ground level and 2 feet thick at the top, with a total

height of 87 feet from base to vane. The exterior stonework is laid in

19-inch courses, while the interior is lined with stone of smaller

dimensions. One cannot do better than quote the Stokes report in paying

tribute to the craftsmanship of these impressive structures.

The rugged stone walls are simple expressions of the idea of

solidity and durability — the functional tradition of the

nineteenth century being worked out in picturesque

forms.37

Another feature, invisible from the ground but mentioned by Stokes,

is that of an artistically designed gutter drain in the form of a lion's

head, an example of careful craftsmanship dating from a time less

utilitarian than our own.

Unlike so many older lighthouses, this one, and perhaps the others in

the series as well, has retained its original lantern. All six

lighthouses were fitted with dioptric apparatus of the latest design

ranging from the 2d Order for Point Clark, Chantry Island, Cove Island,

and Nottawasaga to the 3rd Order for Griffith Island and 4th for

Christian Island.38

A few miles to the north on Chantry Island, just to the south of the

town of Southampton, stands a similar lighthouse again to safeguard

ships from running aground on a dangerous shoal.39 Chantry

Island is uninhabited and so has been the scene of considerable

vandalism; the dwelling is in derelict condition. Department engineers

are considering the lighthouse's demolition because of the high cost of

maintenance, and the replacement of it with a simple steel tower. The

Chantry Island lighthouse, though a handsome and impressive structure,

is one of a type and difficult of access.

66 Southampton Harbour lighthouse.

(Canada, Department of Transport.)

|

67 Cove Island lighthouse.

(Canada, Department of Transport.)

|

68 Nottawasaga Island lighthouse.

(Canada, Department of Transport.)

|

69 Griffith Island lighthouse.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

The reader will perhaps notice a structural similarity between this

series of six lighthouses on Lake Huron with those built under the

auspices of the same authority in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Strait of

Belle Isle region, completed about the same time (1858) — Point

Amour, West Point of Anticosti and Cap-des-Rosiers, all of which

exceeded 100 feet in height.

Killarney Channel

The two little frame structures, square with sloping sides in the

configuration of a pepper-shaker, built at the entrance to the Killarney

Channel in northern Georgian Bay were probably

the first lights to go into service in the early days of the new

dominion; their revolving lights were lit for the first time on 27 July

1867.40 Of identical design, the one illustrated in Figure 70

is located at Red Rock Point at the eastern entrance to the channel. The

little tower has a half-landing below the lantern deck, which flares out

considerably to form a cornice at the platform. The lantern is of the

familiar polygonal shape. At some later date, the two were converted to

range lights to mark the proper course to enter the Killarney

Channel.

70 Red Rock Point lighthouse, marking the entrance to the Killarney

Channel.

(Photo by author's son.)

|

71 Clapperton Island lighthouse.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

72 Kincardine range light.

(Photo by author's son.)

|

Lonely Island

There are three more lighthouses of sufficient age to merit attention

in the Lake Huron region, although all three are of a common design. The

Lonely Island lighthouse, no doubt aptly named, was built in 1870 in

northern Georgian Bay. An eight-sided frame tower with sloping sides and

fitted with a red circular lantern, this otherwise unremarkable

structure is at time of writing just a century old and is situated in

what appears to be a very exposed location.41

Gore Bay and Strawberry Island

The Gore Bay and Strawberry Island lighthouses (illustrated in Figs.

73 and 74) date from 1879 and 1881 respectively. Both take the familiar

form of square, slightly tapering towers with attached dwellings and are

set on stone foundations. Strawberry Island lighthouse, 40 feet in

height, has two landings within the tower whereas the somewhat lower

tower at Gore Bay has but one. In each case, polygonal lanterns are

mounted on square projecting lantern platforms.

73 Gore Bay lighthouse, Manitoulin Island.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

74 Strawberry Island lighthouse.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Lake Superior

Quebec Harbour and Porphyry Island

The most northerly and most

extensive of the five Great Lakes and credited with being the largest

body of fresh water in the world. Lake Superior has few lighthouses of

any historic interest, and those in generally offshore, inaccessible

locations. The first lighthouse was built in 1872 at Quebec Harbour on

Michipicoten Island. As may be seen from Figure 75, this structure

consisted of a one-storey frame house with a range light shining from a

dormer window. The present facility at Quebec Harbour still answers this

description in the current list of lights.42 The second

lighthouse to be built on Superior's shores was on Porphyry Island in

1873, at the entrance to Black Bay in the vicinity of Port Arthur

(Thunder Bay). This lighthouse has been replaced.

The bulk of lighthouse construction on Lake Superior has been carried

out over the course of the past 30 to 40 years: open-work steel towers.

mast and pole lights predominate.

75 Quebec Harbour lighthouse, Lake Superior.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Upper St. Lawrence River

Since lighthouse construction in the upper St. Lawrence got under way

so much later than on Lake Ontario, its description follows that on the

Great Lakes. In point of fact, early lighthouse construction on the

upper St. Lawrence was contemporaneous with that on Lake Huron.

The first of the upper St. Lawrence lighthouses on the low-lying

shore of placid Lake St. Francis was that at Lancaster Bar, built in

1844. This lighthouse, according to information furnished by the

Dominion Lighthouse Depot, was a 20-ft square frame tower of a type

frequently seen on inland waters. It is still standing, though no longer

in use. A lighthouse of similar design but twice the height was built on

Cherry Island in 1847; this light is no longer listed. A square wooden

tower appeared on Magee Island in 1848, and a lantern was installed on

the roof of a house at Coteau Landing the same year.43

By the mid-1850s, the advent of the river steamer and its increasing

use by night called for the lighting of the intricate channels threading

their way among the scenic Thousand Islands. A series of nine small

lighthouses following the familiar design of square frame and sloping

sides was built at Cole's Shoal, Grenadier Island, Fiddler's Elbow,

Lindoe Island, Jack Straw Shoal, Spectacle Island, Red Horse Rock, Burnt

Island and Gananoque Island. An official report compiled in 1855 boasted

that this stretch of the river "is now lighted as a

street."44

Of all these small river lighthouses, only Cole's Shoal is still

standing though it is no longer in use. The Red Horse Rock lighthouse,

which may be taken as one of typical design on in land waterways,

survived until 1968. This lighthouse was built in 1855, set on a

foundation of piers in the river. The 26-foot frame tower, 12 feet to a

side and with a slight taper, was lined with narrow clapboarding and

capped with a plain cornice. The

octagonal lantern rested on a four-foot square box. The cupola was

described as ogee in configuration; that is, embodying a double

continuous curve.45 Although reported in good condition, the

little lighthouse, then over a century old, has since given place to one

of the economical and utterly functional circular steel towers which are

appearing in ever greater profusion on our inland waterways.

A surviving example of one of these small river lighthouses, dating

from 1874 and believed to be the original, is located at Knapp Point on

the north shore of Wolf Island. Its lantern has been removed and

replaced with a steel buoy structure on which is mounted a rotating

beacon.

A considerable need was felt for a light in the Prescott area in the

years following Confederation. In 1873, the Department of Marine

purchased a former windmill located a mile below Prescott which they

converted to a lighthouse for the sum of $3,266.27. The lantern atop the

62-foot stone tower originally housed four flat-wick coal oil lamps

fitted with 16-inch reflectors exhibiting a fixed white

light.46 The Windmill Point lighthouse is still in use,

showing a dioptric light of the 5th Order.

76 Windmill Point lighthouse.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Although the lighthouse per se is now nearly a century old, the

principal interest in this structure is rather related to its function

before conversion to serve the interests of river navigation. It was

this windmill which gave its name to the decisive action, fought on a

cold and dark November day in 1838, in which an American filibustering

force under the command of a Polish "nobleman" met decisive defeat at

the hands of a mixed force of British regulars, marines and Canadian

militia. The Americans took refuge in the windmill, from which they

defied the besiegers until guns brought down from Kingston forced their

surrender. A plaque affixed to the lighthouse wall donated by a

Polish-American patriotic association in memory of the unfortunate Von

Schoulz is a fitting tribute to the amicable relations which have for so

long existed along the undefended border.

|