|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 9

The Canadian Lighthouse

by Edward F. Bush

Administration

From 1763 until 1805, boards of commissioners were appointed for

specific public works in Lower Canada. In that year, following the

British tradition, a corporate body to be known as the Quebec Trinity

House was created by statute, with

full power and authority, to make, ordain and constitute such and

so many Bye laws, Rules and Orders, not repugnant to the maritime laws

of Great Britain or to the laws of this Province. . . . for the more

convenient, safe and easy navigation of the River Saint Lawrence, from

the fifth rapid, above the city of Montreal, downwards, as well by the

laying down, as taking up of Buoys and Anchors, as by the erecting of

Lighthouses, Beacons or Land Marks, the clearing of sands or rocks or

otherwise howsoever.1

In addition to the master and his deputy, two wardens were appointed

in Quebec and three in Montreal, a subordinate branch of the parent

body. The same bill made provision for divers other officials as a

harbour master for Quebec, and at Montreal water bailiffs,

superintendent of pilots and a lighthouse keeper at Green Island "with a

farm belonging to the Corporation."2 A little over a

quarter-century later, a Montreal Trinity House was instituted, the

enabling statute receiving royal assent on 25 February 1832.3

These two authorities were not unworthy of their namesake in London,

co-operating fully with the Admiralty, the imperial boards of trade, and

the various boards of lighthouse commissioners in the Atlantic

provinces, to be succeeded only at Confederation by the newly created

Department of Marine and Fisheries.

By the year 1824, the colony of Nova Scotia was maintaining five

lighthouses along its shore solely financed by means of light dues.

Apparently the Nova Scotian authorities at this time felt that they were

contributing somewhat more than their share in relation to their

neighbours, for in the words of a despatch from Government House dated

14 September 1824, "It may not be improper for me to observe here, that

from the geographical position of Nova Scotia, the navigation to and

from the Provinces of New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island derive very

considerable security from its Light Houses."4 From this

date, 1824, more than two decades were to pass before the first

lighthouse was built on the shores of Prince Edward Island; but whether

the Nova Scotia governor's implication with respect to the efforts of New

Brunswick's lighthouse commissioners was well taken is perhaps

debatable.

In 1834, there were 11 lighthouses in Nova Scotia, the south coast,

fronting on the Atlantic and extending about 250 miles, having five by

this date. In addition there was the Halifax Harbour light and one under

construction at Cross Island in the vicinity of

Lunenburg.5

By 1832, the New Brunswick lighthouse commissioners were well content

with the lighting of the Bay of Fundy; so much so that in their report

they contended that "an increase in lights would rather tend to perplex

and embarrass the mariner on his voyage from seaward."6 An

accurate hydrographic survey of the region, so subject to frequent and

dense fog and high tides, seemed more to the point than further

lighthouse construction. In 1832. New Brunswick was maintaining five

lighthouses on the Fundy shore — Gannet Rock, Point Lepreau, Cape

Sable (not to be confused with Sable Island), Seal Island and Partridge

Island. In their report for 1840, the New Brunswick commissioners

contended, on the testimony of American naval and merchant service

authorities, that "The New Brunswick Lights are the best kept of any on

the American coast."7

The hydrographic survey was entrusted to Captain W. F. W. Owen, R.N.

He was commissioned in July 1843 to carry out the project in HMS

Columbia. By 1847 a good part of the Bay of Fundy had been

surveyed, greatly adding to the accuracy and detail on navigational

charts.8 Similar work had been carried out on the St.

Lawrence and the Great Lakes at an earlier date.

In common with the other colonies, New Brunswick levied a light duty

for the upkeep of her lighthouses at the rate of 2-7/10 pennies per ton

on all vessels other than coasters and fishing trawlers. The lighthouse

return for 1847 listed 10 establishments maintained by the province at

annual costs ranging from £99 to as high as £301 (Partridge

Island).9 In addition, New Brunswick contributed to the

upkeep of lighthouses at Cape Sable, Seal Island and Brier Island in the

neighbouring colony of Nova Scotia.10 The New Brunswick

commissioners, like their contemporaries in Nova Scotia, maintained that

their province had done more than its share toward the provision of

lighthouses in the Bay of Fundy, Nova Scotia, for example, contributed

nothing toward the establishments at Machias Seal Island, Gannet Rock,

Head Harbour, Point Lepreau and Partridge Island, lights contributing as

much to the safety of Nova Scotian vessels as to those of New

Brunswick.11

A peculiarity until 1848 of New Brunswick lighthouse administration

was the existence of two boards of lighthouse commissioners, one of

which sat at Saint John and the other at St. Andrews. In 1842, on an

address from the House of Assembly, the Saint John board was constituted

the sole authority in the colony. This decision was resisted for a

season by the St. Andrews body, which refused to sit with its associate.

The Saint John board resolved on 27 April 1842, since separate

appropriations had been provided, to carry on under the old system for

another season while recommending the increased efficiency to be derived

from a single authority. By 1848 this policy had obviously been

implemented, for in the minutes of the executive council, reference is

made to one board of lighthouse commissioners.12 No doubt

this resulted in a saving to the colony.

15 Early diaphone fog alarm, 1904.

(Canada. Sessional Papers.)

|

As with the other colonies, in Newfoundland a board of lighthouse

commissioners was responsible for those

lighthouses which did not fall under the aegis of the Admiralty. By

legislation passed in 1855 the lighthouse commissioners' authority was

henceforth vested in the newly created Board of Works, made up of the

surveyor general as chairman, the attorney general, the colonial

secretary, the president of the legislative council, and three members

from the House of Assembly.13

By the late 1830s it was obvious that Upper Canada's lighthouse

service left much to be desired. In the words of Captain Sandom, master

of the Niagara, whose strictures reached the Colonial Office,

The total neglect of the local government with respect to the

Lighthouses, that a very important one (on Long Point) has literally

been allowed to fall to ruin, the oil being carefully stored in the

contractors' rooms; another (also important) upon Pelee Island, is

in spite of frequent remonstrances by my officers with the keeper and

contractor, kept in utter darkness. I am given to understand the

"Inspector of Lighthouses" is a sinecure office, at present held

by. . .in the City of Toronto.14

Notwithstanding Sandom's sharp criticism, the

inspector general on his 1839 tour of inspection found the Pelee Island

establishment, along with those at False Ducks Island and Nine Mile

Point on Lake Ontario, in reasonable order. He observed, however, that

the reflectors in most of the lights had been damaged by careless

cleaning.

The few good stations notwithstanding, it was nonetheless apparent by

1840 that a closer supervision of lightkeepers was required, and that

some attention should be given to apparatus designed to improve

circulation of air within the lantern. The purchase of supplies by

public contract became mandatory only in 1837. The inspector general

recommended that lightkeepers' salaries be paid only on certification

that the lights in question had been properly maintained either by

ship's captains or local customs collectors.15 Shortly after

the Act of Union, lighthouses in Upper Canada, or Canada West as it was

to be known until Confederation, passed under the jurisdiction of the

Board of Works. A uniform pay scale was introduced for lightkeepers:

£65 per annum on shore stations, £85 on island locations,

and a special stipend of £100 per annum for False Ducks

Island.16 A stricter and more stringent selection of

candidates for lightkeeping duties was instituted in March, 1844;

henceforth, mariners with lake experience would be given

preference.17 Clearly the lax ways of the pre-union period

were a thing of the past, including the mischievous practice of hiring

deputies (sub-contracting the duties to third parties) which so often

had contributed to carelessness and neglect.

But not all complaints could be traced to a negligent keeper.

Frequently the sperm oil lamps smoked, darkening the lantern glazing and

so diminishing the effectiveness of the light. In December 1844, J. S.

Mcintyre reported to the Board of Works that the trouble lay with poor

combustion due to inadequate ventilation. The solution

to this problem was a properly designed air vent in the roof of the

lantern. He also observed that many of the burners were not set at the

exact focal point of the reflectors, and to correct this fault he made

all of the reflectors adjustable.18 He also recommended the

standardization of all the lamps and reflectors in use on the lakes, and

this was later implemented. Other improvements were made in the lamps to

regulate the flow of oil to the wick and reduce oil

wastage.19 Of all the lights on the lower lakes, Mcintyre

found the worst attended was that at Port Burwell.

It is fortunate that this Light is not of much consequence for it

is certainly the worst attended to on the Lakes. The reflectors are of

very little use as the lamps are three inches outside of the focus, and

there is no way of altering them, without making an entire new

stand.20

Mcintyre's modifications of apparatus and reforms respecting

personnel had their effect, for by 1845 he was able to report that all

the lights on Lake Erie were of a new and improved design, as were those

at False Ducks, Main Ducks and Point Petre on Lake

Ontario.21

With the creation of the new Department of Marine, not many years

were to pass before it assumed responsibility for aids to navigation

from its colonial predecessors in the various provinces of British North

America. In 1870, the new federal parliament enacted legislation

transferring responsibility for all lighthouses and buoys between Quebec

and the Strait of Belle Isle from the Quebec Trinity House to the

Department of Marine. The Montreal Trinity House surrendered its

jurisdiction in like manner on 1 July 1873.22

In 1867 the total number of lighthouses established and in service

in the old Province of Canada (Quebec and Ontario) was tallied at

131.23

|

| Strait of Belle Isle to Quebec | 24 |

|

| Quebec to Montreal | 27 |

|

| above Montreal | 69 |

|

| above Montreal (privately run) | 11 |

|

Although this may have seemed at the time an impressive total, with

the rapid development of steam navigation the new department early in

its career recognized the urgency for both expansion and improvement in

quality. The minister, in his fifth annual report (1872) stated,

I was under the necessity of asking for moderate sums, and erecting a

cheap description of strong wooden-framed buildings, taking care,

however, to use nothing but high-class powerful lighting apparatus: . .

. this Department has succeeded in erecting ninety-three new lighthouses

and has established four new lightships, and ten new steam fog alarms on

the coasts of Canada, besides having under contract forty-three

lighthouses, eight steam fog alarms, and two new light ships, all of

which has been done within five or six years. The Canadian petroleum oil

used for these lights, being a powerful illuminant, and being procured

at a very small cost, has enabled this Department to maintain not only

brilliant and powerful lights, but to do so at, probably, a cheaper rate

than any other country in the world.24

In the summer of 1872, a visiting committee of the imperial Trinity

House toured both Canada and the United States in order to observe the

quality and efficiency of their respective lighthouse services. The

visitors found the Canadian lights superior to the American, although

the latter service comprised a greater number of solidly built masonry

and brick structures. The Canadian service, they pointed out, had to

operate on a much slimmer budget and so was one of simplicity and

economy, well-suited to the needs of a new country. Lightkeepers were

not highly trained as they were in England, nor were they well paid;

most Canadian keepers considered their lightkeeping wages subsidiary to

other sources of income. According to the visiting Brethren,

Their buildings appear to be easily and quickly erected at small

cost; the mineral oil is a powerful illuminant requiring little care

in management in catoptric lights, and is inexpensive;

moreover, as our experiments show, a higher ratio of illuminating

power is obtained from mineral oil in catoptric lights than in any other

arrangement. Such a system seems admirably adapted for a young

country.25

The Department of Marine handled lighthouse construction estimated at

under $10,000—Bird Rocks, Cape Norman, Ferolle Point and Cape Ray.

Projects on a bigger scale fell to the Department of Public

Works.26

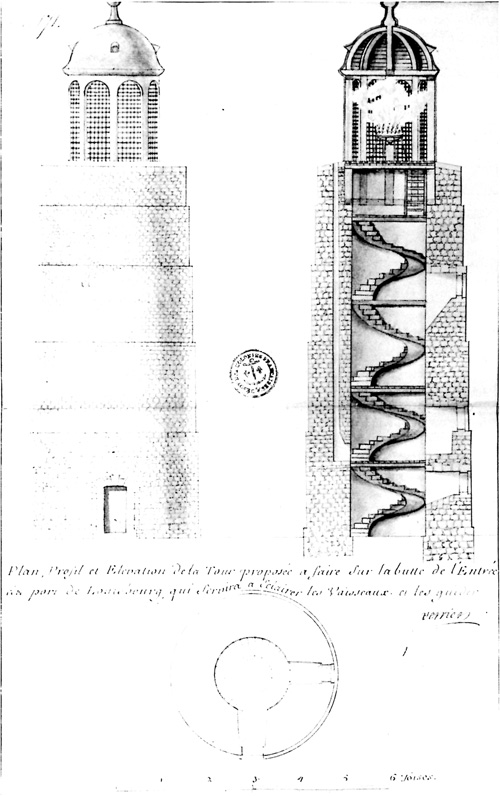

16 Drawing of the Louisbourg lighthouse, the first built

in Canada.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

The Canadian lighthouse service, in these early post-Confederation

years, scarcely compared with that in the British Isles. In Britain, the

equivalent of $100,000 was not considered unusual for the construction

of an ordinary coastal lighthouse consisting of a stone or masonry tower

fitted with dioptric apparatus. A comparable lighthouse in Canada,

frequently of frame construction and fitted with catoptric apparatus,

could be had for only $8,000. The normal staff for a light station in

Britain consisted of three or four uniformed keepers, each of whom had

been thoroughly trained; in Canada, by contrast, frequently there was

but one keeper per light, assisted by his family. Lightkeeping was not

considered a skilled occupation in Canada, hence the preference for

simple apparatus in these early years. In the seventies and eighties,

the British lighthouse service still used whale oil, costing the

equivalent in Canadian currency of 80 or 90 cents per gallon, whereas in

Canada coal oil, a superior illuminant for use with catoptric lights,

cost but 19 cents per gallon.

In like manner the American system reflected a more costly service,

stone towers with several keepers being the rule rather than the

exception. Likewise, American lard oil was considerably more expensive

than Canadian coal oil. The one disadvantage of coal oil was its

inflammable nature. Apart from a score or so of superior lighthouses of

masonry construction fitted with lenticular apparatus, the usual

Canadian facility was of frame construction with simple reflector

apparatus.27 The very length of the Canadian shore line, both

tidewater and inland, particularly with the addition of

the Pacific coast on the entry of British Columbia into Confederation

in 1871, dictated a measure of economy.

By 1876, the Department of Marine had established six regional

agencies responsible for lighthouses, buoys and lightships within their

designated limits:

Prince Edward Island Division

Nova Scotia Division

New Brunswick Division

Quebec Division (St. Lawrence below Montreal and Gulf)

Ontario Division (above Montreal)

British Columbia Division28

Germane to these enterprising developments in lighting equipment was

the institution of the Dominion Lighthouse Depot in a former Prescott

starch factory in 1903. Still active in its original premises, the depot

by its inventive enterprise has largely rendered Canada independent of

overseas suppliers. It has carried out both experimental and

manufacturing processes with all types of burners, lanterns, illuminants

and lenses tested exhaustively to determine which combinations were best

suited to Canadian conditions.

In 1904, a twin development augured well for the future of the

Canadian lighthouse service. The Lighthouse Board of Canada, made up of

the deputy minister of Marine, the department's chief engineer, the

commissioner of lights, the president of the Pilots' Corporation, and a

representative of the shipping interests, was instituted by statute with

broad terms of reference

to inquire into and report to him [Minister of Marine and

Fisheries] from time to time, upon all questions relating to the

selection of lighthouse sites, the construction and maintenance of

lighthouses, fog alarms and all other matters assigned to the Minister

of Marine and Fisheries by Section 2 of Chapter 70 of the Revised

Statutes of Canada.29

In 1911, the Lighthouse Board was re-organized on a regional basis:

the Atlantic division comprising the east coast, Hudson Strait and as

far inland as the head of ocean navigation: the Eastern Inland division

embracing the region from Montreal to Port Arthur at the head of the

lakes, and the Pacific division, including all inland waterways west of

Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay) and the Pacific coast.30 The

Lighthouse Board was active until the creation of the Department of

Transport in 1936, and indeed has never been officially disbanded.

In 1908, the Department of Marine introduced an elaborate and

detailed classification of lighthouses and aids to navigation under no

fewer than 19 categories. Devices in the first six categories were

fitted with fog alarms and the first of these included a rescue service.

Categories 7 to 11 comprised lighthouses without fog alarms, and the

final 8 categories were classed as minor stations "where the exclusive

services of the keeper are not expected." Of these the last two (18 and

19) consisted of wharf lights and lights attended under

contract.31 Lights in the first category, complete with fog

alarms and a rescue service, were Pelee Passage (western end of Lake

Erie), Bird Rocks (Gulf of St. Lawrence northeast of the Magdalens),

Belle Isle (northeast and southwest ends) and Cape Race.32

The second category (main seacoast lights with fog

alarms) comprised another 14 lighthouses, including such well-known

establishments as Point Amour (Labrador coast, western end, Strait of

Belle Isle), Scatarie Island (eastern tip of Cape Breton Island), and

Machias Seal Island and Gannet Rock in the Bay of

Fundy.33

At the outbreak of war in 1914, the total number of lights,

principally lighthouses, along the Canadian sea coast and inland

waterways (especially the Great Lakes), stood at 1,461 of which 105 were

equipped with fog alarms.34

By the spring of 1917, the proliferation of lights along our shores

led the department to discontinue a number of minor ones and to improve

others by means of superior illuminants and better optics. Based on a

1911 recommendation submitted by the Lighthouse Board, agency boundaries

were adjusted to conform more closely to geographical regions. For

example, the lighthouses at Belle Isle, Shippegan (northern New

Brunswick) and Bird Rocks were placed under the jurisdiction of the

Charlottetown agency, whereas Cape Race and Sable Island became the

responsibility of Halifax.35 It should be noted that the

principal lighthouses on Newfoundland's shores were a Canadian

responsibility, and in earlier times, British. The majority of

Newfoundland's lighthouses fell under the jurisdiction, as one would

expect, of that colony's Board of Works.

In November 1936, a new federal department fell heir to the

Department of Marine dating from Confederation, and to that of Railways

and Canals, established in 1879, so combining the function of both. The

new Department of Transport assumed responsibility for all marine aids

to navigation, embracing the functions of the former commissioner of

lights, the chief engineer, and the supervisor of harbour commissions,

hitherto within the purlieu of the old Department of Marine. The

Navigational Aids Branch terms of reference were broadly defined.

This branch has charge of the construction, repairs, and maintenance

of all lighthouses, fog alarms, and other aids to navigation such as

lightships, buoys and beacons, and the Sable Island Humane

Establishment; the surveying, for registration, and recording of all

lands acquired for lighthouse sites; the . . . publications of "List of

Lights", three volumes; the issuing of Notices to . . . and the

administration of all agency shops and the Dominion Lighthouse Depot at

Prescott.36

Regional agencies, in general continuing the organization of the old

Department of Marine, were established at Halifax, Charlottetown, Saint

John, Quebec, Montreal, Prescott, Parry Sound, Victoria and Prince

Rupert, with subsidiaries at Port Arthur, Kenora and Amherstburg, each

of which operated its own supply depot.37 In his first annual

report, the minister stated that the Canadian Lighthouse Service

extended over 52.800 miles of coast line and inland waterways.

With the addition of Canada's tenth province to confederation in

1949, all the lighthouses along the

Newfoundland coast came under the jurisdiction of the Department of

Transport; hitherto, it will be recalled, only landfall and major

coastal lights had been under Canadian operation. Top priority was given

to the modernization of the Newfoundland facilities to bring them up to

the standard pertaining in the rest of the country. To this end, a

comprehensive survey of all Newfoundland's lights and fog alarms was at

once conducted by department engineers and technicians. St. John's

became the scene of a new regional agency serving the same function as

those in the rest of Canada.

|