|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 9

The Canadian Lighthouse

by Edward F. Bush

Lighthouses Along the Atlantic Coast

Until well into the 18th century the coasts of North America

presented a menacing prospect to navigators. The first lighthouse to

exhibit a light on this continent on 14 September 1716 was that on

Little Brewster Island in Boston Harbor.1 Beacon fires on

headlands at the mouths of rivers or entrances to harbours may have been

maintained in earlier times. Presumably vessels under sail and close in

shore anchored by night.

The Louisbourg Lighthouse

A cryptic map reference dated 1828 and prepared under the auspices of

the lieutenant governor of Placentia implies that this early settlement

on the shores of Newfoundland merits the distinction of having been the

site of Canada's first lighthouse. "The old castle where ye lighthouse

is erected ... 1727." Unfortunately research to date has produced no

further evidence to substantiate this claim. Lighthouse literature,

including the work of D. Alan Stevenson and a book of recent publication

by T. E. Appleton, Usque ad Mare, concur that the French fortress

of Louisbourg was the site of the first lighthouse to grace our shores

and the second on the continent.

The project was first broached in November 1727 and was planned to

form a complex along with a hospital and shops on an island in the

harbour entrance. The initial plan envisaged the use of a coal fire as

illuminant. The following month, December 1727, estimates were called

for, A. M. Verrier, the engineer in charge of the project, scotched the

suggestion, based no doubt on motives of economy, that a coal fire be

exhibited from atop the clock tower in the town on the grounds that the

tower was not strong enough for such a purpose. No doubt the fire hazard

also figured in his reasoning.2

The decision to build on the rocky promontory at the harbour entrance

was taken in the spring of 1729. To finance the project, a light duty of

five sols per ton on ocean-going vessels and six livres on

coastal craft was levied in the summer of 1732.3 The

substantial stone tower, a circular structure of coursed rubble some 70

feet in height, was begun on 22 August 1731 and completed two years

later, but delay in delivery of the lantern glazing imported from France

(400 10-inch by 8-inch panes) held up the first lighting of the lantern

until 1 April 1734. A retired sergeant was appointed as lightkeeper.

This simple sperm-oil light consisted of a circlet of oil-fed wicks set

in a copper ring mounted on cork floats, initially without reflectors.

The range of the light was said to be six leagues (roughly 18 miles) in

clear weather.4

17 Lantern and light apparatus, Louisbourg lighthouse.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Faulty design of the lantern incorporating combustible elements

resulted in the gutting of this first structure by fire on the night of

11-12 September 1736. So great was the heat that the cast-iron reservoir

was fused by the fire. Thereupon A. M. Verrier, who had charge of the

lighthouse's construction, opted for a larger reservoir fully 3-1/2 feet

in diameter and 6 inches deep so that, with the lamps spread further

apart, heat within the lantern would be

less intense.5 Further safeguards against fire included

the elimination of combustibles in the lighting apparatus and the

setting of the reservoir containing the cod oil in a water jacket or

bath. Perhaps most significant of all, as shown in Figure 17, the

lantern itself was designed with six stone pillars surmounted by a

vault-shaped brick roof covered with lead. The lantern was

fitted with small vents on each face.6 Cork and solder

were ruled out in the lamp fittings. Local free-stone was used in

construction, the cut stone being clamped together with reinforced iron

supports. By October 1737, work on the new Louisbourg lighthouse was

well advanced with the masonry finished, although delay occurred in

the completion of the ironwork because of a shortage of skilled

artificers in the colony. The new lighthouse was completed in July

1738.7 The tower was 45 feet 6 inches high, with the lantern

adding another 23 feet. By 1751, the lantern was fitted with reflectors

to focus and hence improve the light derived from 32 lamp

wicks.8 The whole installation was subject to monthly

inspection.

The accounts for the year 1739 showed a net revenue from light dues

directed to the upkeep of the Louisbourg lighthouse of 2,882

livres, 11 deniers. The light's operating expense for that

year came to 2,349 livres, 1 sol, 10 deniers. but there

was a surplus of 2,446 livres, 7 sols, and 9

deniers left over from 1738.9 In that year the light

duty for ships plying the high seas was 5 sols per ton, schooners

and local coasters 6 livres per annum, and smaller craft 3

livres annually.10

Canada's first lighthouse was not fated to survive the second British

siege. On 9 June 1758, between nine and ten in the evening, British

batteries and naval vessels opened a heavy bombardment which continued

throughout the night.11 The lighthouse was damaged and after

the fail of the fortress, the victors allowed the structure to continue

to disintegrate, presumably because it was deemed beyond repair. It was

not replaced until 1842.

18 Drawings of Louisbourg lighthouse.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Sambro Island

Sambro Island lighthouse, the construction of which in 1758 was

financed partly by a tax on spirits and partly by the proceeds of a

lottery, is the oldest lighthouse extant on Canadian shores. The Sambro

light was built on a small island of granite rock commanding the outer

approaches to Halifax Harbour; at one time the island was fortified and

several abandoned cannon are to be seen on a rocky prominence to this

day.

In 1758, the Nova Scotia legislative council provided for

construction costs by means of a tax on spirits. This is probably the

only lighthouse in Canada to have been financed, at least in part, by

means of a lottery: 1,000 tickets were sold at £3 apiece with

prizes ranging as high as £500.12 According to the

governor in a despatch to the Colonial Office on 20 April 1759,

This I am to observe to your Lordships, will put the public to no

expense, the charge attending it to be paid out of the savings of the

duties on past imported and retailed spirituous liquors. Out of the same

fund, we are now finishing the inside of the Church.13

The Sambro lighthouse, originally 62 feet in height and solidly built of

stone, was completed on a promontory 72 feet above the water in

1760.14

At first considerable satisfaction was expressed by ships' masters

concerning the new facility, but by 1769 complaints reached the floor of

the legislature that the light money was detrimental to the trade of the

colony and that some of the proceeds were misappropriated.15

A little later, complaints concerning the quality of the light found

their way into official correspondence. The loss of the sloop

Granby off Halifax on 12 May 1771 brought matters to a head.

Having received a letter from Captain Gambier, Commander in Chief of

his Majesty's ships in North America, dated the 12th. of last month, at

Boston, giving an account of the loss of the Granby sloop off

Halifax owing as is believed, to the want of a light being kept in the

Lighthouse at that place; that the Captains of His Majesty's ships are

frequently obliged to fire at the Lighthouse to make them shew a light;

and that the masters of merchant ships complain heavily at being forced

to contribute to the support of a thing from which they receive no

benefit; and which is moreover a great annual expense to

Government.16

Regarding the financial upkeep of the light, the governor in a

despatch of 28 September 1771 stated that a light duty of sixpence per

ton on all shipping entering the harbour of Halifax provided an

operating revenue averaging £184 sterling annually; that the

annual operating expense was calculated at £142, and the balance

went to the contractor, under an arrangement whereby "The person who

manages this Light has undertaken to bear all expenses in consideration

of receiving all the duties laid on shipping for the support of

it."17 This arrangement had been in effect for the previous

two years, based on a recommendation of the legislature dating from 6

November 1769. The governor contended that charges of mismanagement on

this score were without foundation.

Complaints concerning the effectiveness of the light were

attributable to the smoking of the sperm oil lamp, depositing a layer of

carbon on the lantern glazing. This was a common failing, due to insufficient

combustion, of all oil lights before the advent of the Argand burner in

1782. The credit for overcoming this condition went to a Henry Newton,

one of His Majesty's Council, and collector of the customs here. He

has constructed fountain lamps, that give a strong and clear light,

without snuffing, or any supply of oil, during the longest winter night,

with flues that carry off the smoke, which heretofore darkened the

glasses, and almost obscured the light at times.18

The trouble basically had

been due to insufficient lantern ventilation, which no doubt Newton's

modification did much to improve. Complaints continued, however,

concerning the upkeep of the light. Finally in 1774, the

legislature levied light duty on all shipping which passed "from the

Westward to Canso, and other Places to the Eastward of the Harbour of

Halifax," regardless of whether Halifax was a port of

call.19

19 Sambro Island lighthouse, oldest extant in Canada.

(Photo by author.)

|

The Sambro tower was increased to its present 80-foot height at an

unknown date. In 1969, the original cast-iron lantern was replaced with

one of aluminum, and the elaborate dioptric apparatus, made up of finely

ground lenses and prisms of French manufacture with a simple

airport-type rotating beacon, was fitted with a bulldog lens and a

500-watt incandescent light. The current establishment on Sambro Island

includes a 40-watt radio beacon, diaphone, and three neat, well-kept

dwellings, each supplied with a cistern and water purifier. The

shingling on the tapering sides of the tower must be renewed at regular

intervals and the concrete lantern platform is of recent

installation.

In all likelihood, the largest vessel to meet with disaster off

Sambro was the Leyland line Bohemian, of 8,855 tons register,

outbound from Boston to Liverpool, which went aground on Broad Breaker

one mile to the east of the light shortly before three in the morning of

1 March 1920. Fortunately only six lives were lost. No fault was found

with the light or its keeper, but rather with inadequate precautions on

the bridge of the liner. The captain doubted the accuracy of a radio

bearing on Chebucto Head and neglected to take adequate

soundings.20

20 East Ironbound lighthouse, south coast of Nova Scotia.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

McNutt Island

The third lighthouse to be built on the Nova Scotian outer coast, one

of the many long since replaced with newer structures, was on McNutt

Island near Shelburne in 1788. The governor, in a despatch of 18 July

1792, stated that "a large expense has been incurred" in the

construction of an "excellent Lighthouse" at this location. but that due

to a misunderstanding, the light had not seen service until September

1791. The governor boasted that the McNutt Island light was the finest

on the continent and that Captain George of HMS Hussar had rated it

equal to any in the English Channel and that the light had been seen at

a distance of fully seven leagues at sea (i.e., about 25

miles).21

Seal Island

The Seal Island lighthouse, built in 1830 on a small island covered

with stunted conifers some 18 miles off the southwestern extremity of

Nova Scotia, constituted an important landfall light for vessels making

for the Bay of Fundy.

Originally, two married couples, the Edward Crowells and the Richard

Hickens, settled on the island to provide aid to distressed mariners.

Such was the frequency of distress in the vicinity that the Crowells and

the Hickens appealed to the governor. Sir

James Kempt, for the erection of a lighthouse, whose design has been

described as "of massive timbers and pinned with hardwood trenails."

This octagonal tower of very solid frame construction with its circular

cast-iron lantern is in good condition, and apart from the shingling on

the exterior, very much in its original shape. Four straight flights of

stairs connect the three landings and ground floor within the tower.

Crowell and Hickens were the first keepers, at a salary of £30 per

annum.22

21 Seal Island lighthouse, off the southwestern extremity of Nova

Scotia.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

The powerful 2d Order lenticular light, electrified in 1959, is still

fitted with the complex and intricately designed optic made up of lenses

and prisms required before the advent of electricity. No doubt the Seal

Island light has witnessed the whole gamut of progression from seal oil,

mineral oil and petroleum vapour to electricity.

The Seal Island lighthouse should be counted as one of the best

surviving examples of frame construction dating from colonial times. It

is well worth a visit, but the helicopter is recommended for anyone not

sure of his sea legs. The 11 hour run aboard a shallow-draught

diesel-powered lifeboat is not for the peckish or squeamish.

Bay of Fundy

The frequently fog-ridden Bay of Fundy, as a glance at a map would

suggest, became the responsibility of the contiguous colonies of Nova

Scotia and New Brunswick and their respective lighthouse commissioners.

Undoubtedly the first lighthouse in the region was that on Partridge

Island in Saint John Harbour, built in 1791 on the site of a former

fort. This lighthouse, which must be counted the oldest in New

Brunswick, disappeared at a date not determined at the time of writing.

The present concrete tower on the site probably dates from as recently

as 1961. Lighthouse construction along the Fundy shore (under the

direction of the New Brunswick lighthouse commissioners) followed at

Campobello Island in 1829, Gannet Rock and Point Lepreau in 1831,

Machias Seal Island in 1832, and Quaco further up the bay in 1835; of

these the only one to survive in its original form is that on Gannet

Rock.

22 Yarmouth or Cape Fourchu lighthouse of modern reinforced concrete

design.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

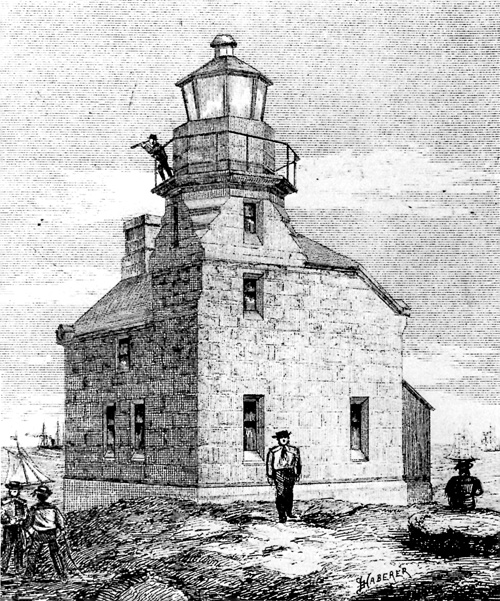

23 Typical harbourlight, Dalhousie, N.B.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Gannet Rock

Constructed on a mere rock islet 7 to 8 miles south of

Grand Manan Island, Gannet Rock lighthouse was a sturdy octagonal frame

tower of substantial hand-hewn timbers after the manner of Seal Island

light. It was six-storeyed, shingled on the outside and set on a stone

foundation later covered with cement. The interior of the tower was

lined with matched lumber. The original brick dwelling attached to the

tower has been replaced with a two storey concrete house.

This 91-foot structure might almost be classed as a wave-swept tower,

and no doubt there are many times when the islet is inundated by high

seas. A gale of unprecedented severity on 18 February 1842 so shook the

foundations as to warrant the building of a granite retaining wall in

1845. The exposed location called for special measures for the

safeguarding of life.

The keepers have a retreat from the upper part of their residence

over the wall into the lighthouse in case of emergency and consider

themselves as secure as they can be in such an exposed

situation.23

Until recent years families used to accompany keepers to this

storm-swept, hazardous location, but now the station is manned by the

two duty keepers only who are relieved each month. The installation of a

dioptric light of the 2d Order indicates that Gannet Rock was considered

on a par with Seal Island.

Demolition was set about in 1967, but with the removal of the leaking

lantern and lantern deck, the tower was found to be in sound condition.

Hence the decision was made to replace the light and optic with a simple

rotating beacon, as at Sambro Island, but without the shelter of a

lantern.

24 Gannet Rock lighthouse, Bay of Fundy.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Machias Seal Island

Machias Seal Island lighthouse in the same region dates from 1832. It

has been replaced with a reinforced concrete tower, probably in 1915.

The original lighthouse was of frame and similar in shape to that at

Gannet Rock. It stood 36 feet in height and showed its light 48 feet

above the high-water mark with a claimed range of 15 miles.24

The reflector-type catoptric apparatus installed at Machias Seal Island,

a cumbersome, less than satisfactory installation, may well have been

typical of the mid-19th century. Within its 7-foot diameter it held 8

parabolic 23-inch reflectors set in a 18-foot circle, each reflector

lighted by one large Argand lamp. Pipes from these lamps led to a common

oil reservoir which was heated in winter by an Argand lamp burning under

it. Not only did the keeper find it difficult to work within this

cramped space, but the lamps were so near the outer frame that the glass

was constantly covered with mist. Captain W. F. W. Owen, R.N., author of

the above report, recommended that one good and sufficient compound

Argand lamp properly fitted with chimney and several concentric wicks

would serve much better.25

25 Grand Harbour lighthouse, Grand Manan Island, N.B., a tower with

an attached dwelling, a common design.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

26 Walton Harbour lighthouse.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Brier Island

In 1807 the legislature voted the sum of £500, to which New

Brunswick added a further £100, for the erection of a lighthouse

on Brier Island, at the extremity of a narrow peninsula known as Digby

Neck enclosing St. Mary's Bay. This light went into service in 1809, and

along with Gannet Rock and Machias Seal Island of later date stood

sentinel at the entrance to the frequently fog-enshrouded Bay of Fundy.

The original Brier Island lighthouse was replaced in 1944 with a

reinforced concrete tower.

St. Paul Island

The rugged fog-bound shores of Cape Breton Island, particularly on

the eastern or seaward side, claimed many an unfortunate vessel in the

days of sail, irregular currents, fog, sudden snow and rain squalls

posed a mariner's nightmare. St. Paul Island and Scatarie Island, the

former lying off the North Cape far out in the Cabot Strait and the

latter off the eastern extremity of Cape Breton Island, were the most

pressing sites for lighthouse construction.

The hazards of the Cape Breton shore were forcefully put by J. H.

Tidmarsh, a Nova Scotia lighthouse commissioner, in 1833.

As our route from Main a Dieu to Louisbourg on our return lay

chiefly on the seashore taking nearly the course of the beaches, it gave

us a melancholy view of the numerous wrecks with which the shore is

strewed, the whole coast is covered with pieces of the wreck of ships

and in some coves there is an accumulation of shipwreck nearly

sufficient to rebuild smaller ones.

The number of graves bore strong testimony also that some guide or

land mark was wanting in the quarter to guard and direct the approach of

strangers to this boisterous rugged shore.26

In the same year a total of 10 ships had been lost on the outer shore

of Cape Breton Island at a cost of 603 lives.27 One of the

worst disasters of the period was the loss of the Astrea, inbound

from Limerick, on Lorraine Head in March, 1834; there were but three

survivors of the 240 souls on board.28

27 St. Paul Island lighthouse, although which of the two originally

built on the island has not been determined.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

The year 1839 saw the establishment of two sorely needed lighthouses

on St. Paul Island, a bleak location well out in the passage known as

the Cabot Strait. The need for a light at this dangerous locality had

been recognized by the Quebec Trinity House as early as 1817. The board

had garnered some preliminary information on the site; the island

consisted of irregular rock covered lightly with soil on which grew

scrubby cedar, pine and spruce. Stone and fine sand were available, but

apparently the former was considered inferior for building purposes for

wood construction was resorted to, despite the advice tendered by the

imperial Trinity House. The Canadian authorities considered that a

lighthouse at this point in conjunction with one on Anticosti Island

would do much to alleviate the navigational hazards of the

region.29 Since St. Paul Island at this time lay outside the

jurisdiction of all the Atlantic colonies, the initiative at the outset

lay with the home government. Lord Dalhousie, governor of Lower Canada,

put the matter before imperial authority in a despatch of 24 March

1826.

As the undertaking is one of great importance to the whole of

British Shipping which resorts to the shores of the Gulph of St.

Lawrence, to the number of more than 100 sail annually, I entertain a

hope that His Majesty's Government will view the measure as in some

degree one of National concern.30

The imperial treasury concurred in June 1829 in sharing the cost of

the project with the colonies concerned, but ruled that Newfoundland be

excused a contribution.31 Whereupon the Lower Canada House of

Assembly on 17 March of the following spring (1830) resolved that a sum

of up to £2,000 be authorized as the province's share in

construction, and that one-half the annual cost of upkeep be met from

the funds of the Quebec Trinity House.32 The Nova Scotia

treasury administered the funds, rendering annual accounts through the

legislature to each of the contributing provinces. The Nova Scotia

lighthouse commissioners took charge of construction, both at St. Paul

Island and at Scatarie. Six commissioners were appointed in 1836 from

the participating colonies to determine the site; Samuel Cunard (founder

of the celebrated Cunard Line) and Edmund M. Dodd from Nova Scotia,

Augustin N. Morin from Lower Canada, Thomas Owen from Prince Edward

Island, and Alexander Rankin and William Abrams from New Brunswick. In

addition to the selection of suitable sites at the two locations, the

commissioners were to determine the type of structures to be built and

to reach agreement on shared maintenance costs.33 Lower

Canada headed the list with a £500 annual commitment. New

Brunswick offered £250, Prince Edward Island £30, and Nova

Scotia £250 for the first year's operation and thereafter

sufficient to make up the total sum of £1,030.34

28 St. Paul Island, southwest point, short circular iron tower.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

"Two good and sufficient lighthouses, with bells and guns" were

ordered for St. Paul Island in August 1836.35 The

establishment was to include a life-saving station consisting of six men

with boats and full provisions. The need for the humane establishment

had been tragically demonstrated in the light of the frequency of

disaster in the recent past; to such a degree, indeed, as to affect

immigration. As recently as 1834, the immigrant ship Sibylle,

bound from Cromarty to Quebec, foundered off St. Paul Island with the

loss of all 316 passengers aboard. In its issue of 23 September 1834,

the Royal Gazette published in Charlottetown could scarcely have

put the case for a light in stronger terms.

Good God! can nothing be done to erect a lighthouse on that fatal

island? Surely means should be taken if possible to prevent such

dreadful shipwrecks.36

The Sibylle was one of a numerous and ill-fated company to

meet her end on St. Paul Island. Nonetheless, five more years were to

pass before the long-sought lights were finally in service.

Bayfield and the lighthouse commissioners appointed by the colonies

agreed on the sites for the two St. Paul Island lighthouses in the

summer of 1837, but felt that the lights at either end of the island

should be so dissimilar as to preclude the possibility of mistaking one

for the other. The Admiralty, which was shouldering the main burden of

the construction costs, insisted that one of the lights should be made

either a flashing or revolving one.37 The site was a

difficult one for construction, there being no harbour and only two

beaches available for the discharge of heavy stores. Fog was prevalent.

Although a report printed in the Lower Canada Journals of the

Legislative Assembly of 1830 described granite found on the island

as suitable building material, the officer commanding the Royal

Engineers in his report recommended the use of 40-foot wooden towers

resting on 5-foot foundations.38 The two lighthouses were

finished in 1839; one was built on a rock off the north point of the

island and the other on the south point. about 150 feet above the water.

The estimates were exceeded on several occasions, and the imperial

treasury was approached for additional funds. Since the St. Paul Island

installations were included with the Scatarie Island project in the

estimates, it has not been

possible to determine individual construction costs. One considerable

difficulty was the supply of labour for such a relatively isolated

location. Once built, the lighthouses were to be maintained by the four

colonies themselves, but in the event of their loss, Britain would

share the cost of reconstruction.

A statement submitted by the Nova Scotia commissioners in 1847

records the contributions of the four colonies toward the maintenance of

the St. Paul Island and Scatarie establishments for that

year.39

|

| Canada | £601 | 4s. | 10d. |

|

| New Bunswick | 250 | 0s. | 0d. |

|

| Nova Scotia | 351 | 4s. | 11d. |

|

| Prince Edward Island | 36 | 1s. | 6d. |

|

| Total | £1,238 | 11s. | 3d. |

|

An annual report of the Department of Marine and Fisheries for the

season 1873-74 described the lanterns in both lighthouses as of iron,

10-1/2 feet in diameter, fitted with plate glass of dimensions 20 by 24

inches. By this date lenticular apparatus had replaced the catoptric

first installed, and presumably the lamps were burning a vegetable oil

in place of sperm oil. Complaint was made of the lights themselves, of a

pattern which failed to do justice to the fine optical apparatus

provided.40 By 1889 the St. Paul Island lighthouses had been

re-furnished with 12-foot iron lanterns which enabled "new pressure

lamps sent to the island two years ago" to be installed, producing a

much better light.41

The lighthouse at the southern end of St. Paul Island together with

its adjoining dwelling was destroyed by fire in December 1914.

Replacement with a new, short cast-iron tower designed and built at the

Dominion Lighthouse Depot in Prescott was taken in hand at once.

Transported from Prescott in sections, the 12-foot tower was assembled

at Halifax. The short round tower supported a 10-foot-high lantern with

octagonal outer gallery. Total height of the structure base to vane was

27 feet 6 inches. The 4th Order flashing petroleum vapour light produced

35,000 candlepower. This light was scheduled for service on 1 March

1916.42 With good visibility the light had a range of 16

miles. Total cost of construction, materials, labour and optical

apparatus amounted to $9,175,43 with final revision for

incidentals to $10,340.16. This lighthouse, an excellent photograph of

which is shown in Figure 28, stands today, but its companion at the

north end of the island has been replaced by a concrete tower with

aluminum lantern within the past decade.

Scatarie Island

Scatarie Island was the principal landfall for ships making for

Sydney, Pictou, Miramichi and Quebec. In 1833, the Nova Scotia

legislature granted £500 as its share in the cost of establishing

a light at this point. The project, in conjunction with that on St. Paul

Island, was to be a joint undertaking on the part of Nova Scotia, New

Brunswick, Lower Canada and the imperial government.44 The

project had been the subject of a merchants' petition to the Admiralty,

possibly following the loss of the transport Leonidas on the

island of Scatarie in 1832, in which both troops and crew were lost

along with a consignment of gold.45

As were the structures on St. Paul Island, the lighthouse on Scatarie

was of wooden construction, contrary to the counsel of the British

Trinity House, on the grounds that stone would be too difficult and

costly to transport to the two sites. The Scatarie Island light was

exhibited for the first time on 1 December 1839, the establishment to be

maintained by a keeper and one assistant.46

The first lighthouse on Scatarie Island has been replaced in recent

years by a 13-foot steel skeleton tower. The catoptric light listed in

the 1970 List of Lights, Buoys and Fog Signals is one of the few

purely reflector-type lights, apart from range lights, still in

service.

Newfoundland

Britain's oldest colony until recent years, by reason of its command

of the two entrances to the Gulf of St. Lawrence and its proximity to

one of the richest fishing grounds in the world on the Grand Banks, was

very much a seafaring dependency. Lighthouses, therefore, were among the

early projects of Newfoundland enterprise. A number of the more

important lights on her shores served the interests of the Canadas and

the maritime dependencies more than those of Newfoundland, and for this

reason a number were built and maintained by imperial and later by

Canadian authority.

Fort Amherst

The first lighthouse in Newfoundland (save for the

possibility of one at Placentia early in the 18th century) was

established at Fort Amherst at the entrance to the harbour of St.

John's. The Quebec Trinity House minutes record that a light was first

exhibited here in 1811,47 but the rare and beautiful though

unpublished work of Robert Oke, Newfoundland lighthouse inspector, dates

the establishment of the Fort Amherst lighthouse from

1813.48 The lantern in the form of a cupola rose from the

house roof, a common design in early Newfoundland lighthouses. The walls

of the house, fully two feet thick, were of stone set in Portland

cement. Voluntary contributions maintained the Fort Amherst light until

the establishment of the colonial legislature in 1832. In 1852, a

triple-wick Argand burner fitted with an annular lens provided

Newfoundland with its first dioptric light.

29 Fort Amherst lighthouse at the entrance to St. John's Harbour.

(Robert Oke, "Plans of the Several Lighthouses

in the Colony of Newfoundland," Unpubl. MS.)

|

Cape Spear

In 1836, a lighthouse of similar design was built at Cape Spear on

the approaches to St. John's Harbour. The lighting apparatus,

transferred from the Inchkeith lighthouse on the Scottish coast,

consisted of seven Argand burners fitted with reflectors for which a

range in clear weather of 36 miles was claimed. A concrete tower

replaced the original Cape Spear lighthouse in 1963 which, however, is

being preserved by the crown.

30 Cape Spear lighthouse. This is a good example of the lantern

mounted on the roof, common among the older structures in Newfoundland.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

31 Trinity North lighthouse, Newfoundland. The circular iron tower

was frequently used on these coasts. In this instance the attached shed

formerly served as the roof of a house blown off in a storm.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Harbour Grace Island

The third lighthouse to grace Newfoundland's

shores was built on Harbour Grace Island, first seeing service on 21

November 1837. Like its predecessors, the Harbour Grace lighthouse

essentially was a house with the light showing from a cupola on the

roof. A despatch from Government House dated 27 November 1837

stated,

I have the honor to inform your Lordship that on the 21st. Inst.

a powerful fixed light extending eastwardly, or seaward, from N to SW by

compass was exhibited, and will continue to be exhibited, from sunset to

sunrise on Harbour Grace Island in Conception Bay.49

Again a Newfoundland lighthouse was to benefit from the conversion to

improved apparatus in the British Isles. The catoptric apparatus,

consisting of 15 Argand burners and silver reflectors, was shipped out

from England, where it had served in the Isle of May lighthouse, for use

in the Harbour Grace structure.50 In 1865 the lighthouse,

threatened by coastal erosion, was moved back 65 feet from the

shore.51 The old Harbour Grace lighthouse was replaced in

1961 with a graceless, open-frame galvanized tower.

Cape Bonavista

The fourth of these early Newfoundland lighthouses, of similar design

to the preceding three, was built at Cape Bonavista in 1843. The cost of

construction, complete with light, was £3,024 10s., and its annual

upkeep was established at £375.52 The revolving light

exhibited both a white and a red characteristic from an overall height

of 150 feet above high water. The anticipated range from all quarters

seaward was 30 miles.53 In 1966, after nearly a century and a

quarter in service, the old Cape Bonavista lighthouse was replaced by a

tower of skeleton steel. The province is preserving the old lighthouse

(see Fig. 32) complete with the original lighting apparatus made

up of 16 Argand burners with reflectors transferred from the famous Bell

Rock lighthouse on the east coast of Scotland.

With the completion of the Cape Bonavista lighthouse in 1843, four

lighthouses were maintained by Newfoundland on her east coast. For a

colony of more slender resources than either Nova Scotia or New

Brunswick, Newfoundland had made a commendable effort. The first four

lighthouses served the St. John's trade, but there were as yet no lights

on the perilous south coast so subject to fog off the Grand Banks.

Navigational facilities here, however, were of more significance to the

St. Lawrence trade than to that of Newfoundland.

32 Cape Bonavista lighthouse, now no longer in use but preserved by

the province.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Cape Pine

Particularly was the lack of a light felt on the southern coast of

the Avalon Peninsula, lying as it did nigh the shipping lane for

vessels bound for the St. Lawrence. A number of vessels had met with

disaster along this rocky, indented and frequently fog-bound coast. In a

despatch to the Colonial Office dated 7 November 1840, the governor of

Newfoundland, Sir John Harvey, had enclosed the legislature's petition

for the erection of a lighthouse on Cape Pine at the southernmost

extremity of the Avalon Peninsula. The mounting toll of ships and lives

had been a matter of concern since 1837.54 The colony's

slender resources frequently necessitated appeals to the mother country

for such projects. In this instance, the imperial government responded,

but Newfoundland's neighbours did not. In 1843 the governor of

Newfoundland sounded out the Canadian authorities for the construction

of a lighthouse at Cape Pine. The Montreal Trinity House concurred in

Canada's assuming a share of the expense, but the Quebec authority

contended that other sites in the region would better serve Canada's

interests, and so advised against Canadian participation in the project.

The executive council so advised the Newfoundland governor.55

The colony had found ready support, however, in London. Parliament

appropriating the sum of £2,000 sterling for the construction and

outfitting of a lighthouse on the south coast of Newfoundland, to be

maintained by the colony once completed. The contractor's

tender56 for £6.514 9s. 6d. comprised the

following items:

|

| Cast-iron tower, with gallery and railing stairs,

ventilators, windows, doors, etc. |

£2.192 |

5s. |

0d. |

|

| lantern |

2,330 |

0s. |

0d. |

|

| freight, shipping insurance, landing,

hoisting up cliff, inland transport, foundation, resident engineer &

workmen from England |

400 |

0s. |

0d. |

| 700 |

0s. |

0d. |

|

| screaming apparatus (fog alarm) |

300 |

0s. |

0d. |

|

| contingencies |

594 |

4s. |

6d. |

|

The Cape Pine lighthouse, still standing today, was a circular 50-foot

cast-iron tower (a type to be frequently resorted to in Newfoundland)

whose revolving light scanned the sea from a height of fully 300 feet.

The catoptric light originally incorporated 16 burners and reflectors

but these later were reduced to 12.

33 Cape Pine lighthouse, a 50-foot cast-iron tower, a controversial

design in Newfoundland. The light was fully 300 feet above the sea.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

The Cape Pine lighthouse went into service on New Year's Day, 1851.

The installation was at once handed over to the Newfoundland Board of

Works, which maintained it thenceforth at a cost of about £395 per

annum. The tower at first included living quarters, but the damp quickly

rendered these uninhabitable, and so a separate dwelling had to be

built.57 In its report for 1851, the Newfoundland Board of

Works reflected critically on the refusal of the neighbouring Atlantic

colonies to share in an endeavour as much in their interests as in those

of Newfoundland.58 In light of this it is perhaps not

surprising that Newfoundland a few years later withheld contributions

for the Cape Race light.

Cape Race

By all odds the famous Cape Race lighthouse, commanding the busiest

shipping lanes on the approaches to British North America, was the most

important landfall light ever established on our shores. As early as

1838, the Elder Brethren of Trinity House selected Cape Race as the best

site for a lighthouse by which ships making for the gulf could take

their bearings. With the installation of the efficient lights on St.

Paul Island, a suggested site at Cape Ray on the Newfoundland shore of

the Cabot Strait was thought less important.59 No doubt the

Elder Brethren considered at this early date that the St. Paul Island

lights were sufficient for the 75-mile-wide strait, and in fact a light

appeared on the Newfoundland side only in 1871. The designer of the Cape

Race lighthouse, as well as of its predecessor at Cape Pine, was the

civil engineer Alexander Gordon.

The Cape Race project got under way in the spring of 1855, like Cape

Pine entirely under imperial authority. At the request, however, of the

Newfoundland lighthouse commissioners, who had had misgivings concerning

the utility of iron in such a climate as theirs, stone construction was

resorted to rather than cast iron. The circular 68-foot tower was built

on a site 178 feet above the sea. A red circular iron lantern originally

housed a catoptric light (fixed) made up of 13 Argand burners with

reflectors; the light was visible from northeast by east through south

to west.60 The Cape Race tower was provided with living

quarters consisting of a circular shelter built about the tower's base;

the two apartments fronting seaward were used only as

storerooms, and the other four accommodated the keepers and their

families. This accommodation would not be forgotten by those who

initially used it. A leaking roof, condensation and hoarfrost lining the

walls and smoking chimneys dictated the early provision of a separate

dwelling for the keepers and their families. The Cape Race lighthouse

was finished in October, 1856, and went into operation on 15 December of

the same year, with an initial supply of 350 gallons of seal

oil.61 With an anticipated consumption of 600 gallons per

annum, operating costs were estimated at £130 annually. A light

duty of one-sixteenth of a penny per ton was levied by the imperial

government in March 1857 on all transatlantic shipping bound for or

departing the gulf.62 Tolls were to be collected at ports of

clearance, and the governor of Newfoundland was to render accounts

quarterly to the Board of Trade in London covering the cost to the

colony of maintaining and operating the light.63 The total

maintenance costs of the Cape Race lighthouse for the year 1860 stood

at £471 10s. 0d., of which Canada's share was £169 15s.

1d.64

34 Cape Race lighthouse.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

The first Cape Race light, destined to become the most powerful on

our shores, was not satisfactory. The trouble was that each of the 13

Argand lamps and reflectors illuminated too broad an arc (14 degrees);

however, in order to concentrate the beams for optimum effect calling

for an arc of no more than 5 degrees per lamp, no fewer than 68

reflectors would have been required, an installation which even the

largest lantern could in no

way accommodate.65 The ultimate solution was the

substitution of a 1st Order lenticular apparatus, but this was not

resorted to until much later.

The Cape Race light had not been a fortnight in operation when the

first of several ships foundered within hailing distance, yet unable to

see the new facility. On Christmas night 1856, the Welsford, of

1,293 tons register outbound from Saint John for Liverpool, ran aground

within two miles of Cape Race with the loss of her captain and most of

her crew. Had it not been for the strenuous and valiant efforts of the

lighthouse crew, the four survivors would have perished in the surf. The

mate testified that the light had been completely obscured in the fog

and suggested the provision of a signal gun to be used in such thick

weather.66 A few years later on the night of 12 October 1863,

the passenger liner Africa foundered off Cape Race; so thick was the

weather on this occasion that even the ship's officers testified that no

light regardless of brilliance could have saved the

Africa.67

Notwithstanding these extenuating circumstances, it was recognized

that the Cape Race light left something to be desired. In 1864 Robert

Oke, the well-known Newfoundland lighthouse inspector under whose

direction eight of the twelve Newfoundland lighthouses had been built,

recommended that in the interest of readier identification, the Cape

Race light be changed from a fixed to a revolving one. The new catoptric

apparatus comprised nine burners and reflectors.68 The

governor accepted the recommendation. The London firm of DeVille &

Company supplied the new light, complete with "gun metal wheels enclosed

in a mahogany case and provided with the necessary cord, weights and

pulley," cast-iron and gun-metal lantern.69 The conversion of

the Cape Race light was carried through in 1866, and simultaneously the

Cape Pine light, again on the recommendation of Robert Oke, was changed

to a fixed light.

In 1886, 30 years after its construction, the Cape Race lighthouse

was transferred to Canadian jurisdiction, taking effect on Dominion Day

of that same summer, together with the sum of $100,151.50 in light dues,

on the sole condition that Canada maintain it henceforth without the

imposition of light duty.70

In 1906 work began on a new lighthouse at Cape Race which is still in

service, very close to the original site (the difference being 12" of

latitude and 1'39" longitude). The new circular stone and concrete tower

rose 68 feet from the base to the lantern platform, 96 feet overall base

to vane. The three-foot thick wall was 20 feet in diameter, rising

perpendicularly to the lantern platform or balcony.71 A

lantern 17 feet 1-1/2 inches in diameter, larger than any hitherto

mounted on our shores, housed the single-flash petroleum vapour light,

described as hyperradial (beyond the dimensions of a 1st Order light).

This massive lenticular apparatus rotating effortlessly on its mercury

float produced a flash of more than one million candle power. The new

light, manufactured by the well-known Birmingham firm of Chance

Brothers, went into service in the spring of 1907.

The Cape Race light was electrified sometime in 1926-27, fed by a

Delco generator in a nearby power house. The lenticular apparatus

installed in 1907 was retained, however, and to our knowledge at time of

writing is still in use.72 Cape Race is still a manned light

station, one of the few on Canada's coasts.

35 Rose Blanche lighthouse, Newfoundland, illustrative of design with

lantern mounted on the roof of a house.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Cape St. Mary's

In 1860, Newfoundland added a third light to her rugged south coast

on the lofty promontory known as Cape St. Mary's 325 feet above the sea.

Construction was of brick with separate dwellings for the staff. The

revolving light on the catoptric principle employing a dozen burners was

pronounced by a parliamentary commission to be second to none of its

type in the British Isles. Great difficulty was experienced in landing

this weighty and delicate apparatus on the rocky shore and hauling it up

to the site; nonetheless, the light was ready for service on the night

of 20 December 1860. A range of 14 leagues (about 42 miles) was claimed

for it in good weather.73 The old St. Mary's lighthouse has

been demolished and replaced with a new structure within recent

years.

Cape Ray and Channel Head

Cape Ray, built by the Canadian government

in 1871, and Channel Head, erected by Newfoundland in 1875, provided

lights complementary to those on St. Paul Island on the Cape Breton side

of the strait. Cape Ray was replaced with a new lighthouse in 1960.

Unfortunately information is skimpy on the origins of the Channel

Head lighthouse a dozen miles or so southeast of Cape Ray. Construction

of a light on this site was recommended by a Captain John Orlebar, R.N.,

in 1864. It is not clear from information presently on hand whether the

Canadian government shared the construction costs or not. In any case, a

lighthouse of circular iron construction was completed in 1875 on

Channel Head, 40 miles from St. Paul Island.74

36 Channel Head lighthouse in typical weather along the Newfoundland

coast.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

|