|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 9

The Canadian Lighthouse

by Edward F. Bush

The Gulf, Northumberland Strait and the Lower St. Lawrence

Access to the gulf is gained by the Strait of Belle Isle and the

Cabot Strait to the north and south of Newfoundland respectively. The

northern route, an ice-beset channel until well into mid-summer, offers

the shorter passage to the British Isles from Quebec and Montreal. In

the days of sail Belle Isle was avoided, but with the coming of the

steamer by mid-century, the 15- to 20-mile-wide channel between the

inhospitable Labrador and Newfoundland coasts attracted more shipping.

The advent of the 17- to 18-knot

subsidized mail steamer by the year 1905 accelerated this trend. A

light did not mark this northerly passage until 1858, and as will be

recalled from the previous chapter, only in 1839 had the mariner in the

Cabot Strait the benefit of the two lights on St. Paul Island. Inasmuch

as the bulk of the shipping used (and yet does) the southern route, it

received the first attention.

The increased steaming speeds in the latter half of the 19th century

demanded a substantial improvement in navigational aids. The president

of the veteran Allan Line, the principal steamship company in the

Canadian service, put the issue bluntly to the Canadian government in

1869. Among the measures mandatory if Canadian aspirations for a fast

mail service operating to the St. Lawrence were to be realized, the

following lighthouse projects must have high priority:

|

| Bird Rocks estimate | $13,000 |

|

| Anticosti Island, South Point | 10,000 |

|

| Magdalen Islands (Dead Man's Rock) | 6,500 |

|

| Cape Ray | 11,000 |

|

| River Magdalene | 6,000 |

|

| Cap Chat | 6,000 |

|

| Ferolle Point | 22,000 |

|

| Cape Norman (Strait of Belle Isle) | 22,000 |

|

| Seven Islands (north shore) | 6,000 |

|

| Red Island Reef (lightship) | 14,000 |

|

Construction at these sites was authorized by an order in council

dated 14 January 1870.1 Short of such an outlay, aggregating

$95,000, the chimerical "Canadian Fast Line" would never be

feasible.

Belle Isle

Over a period of a half-century, three very important lighthouses

were built at the Atlantic entrance to the Strait of Belle Isle on the

long tapering island of rugged contour bearing the same name. Undertaken

by the Canadian Board of Works, the first of these was constructed on a

highly inaccessible site at the south end of Belle isle, 470 feet above

the sea. An access road approximately a mile in length had first to be

built from the beach to the site. At some points the gradient approached

40 degrees. The cliffs fell away precipitately to the shingle, and no

cove or harbour lay within 20 miles. The extreme difficulty experienced

in landing and hauling bulky and delicate apparatus under such

conditions may be readily appreciated.2

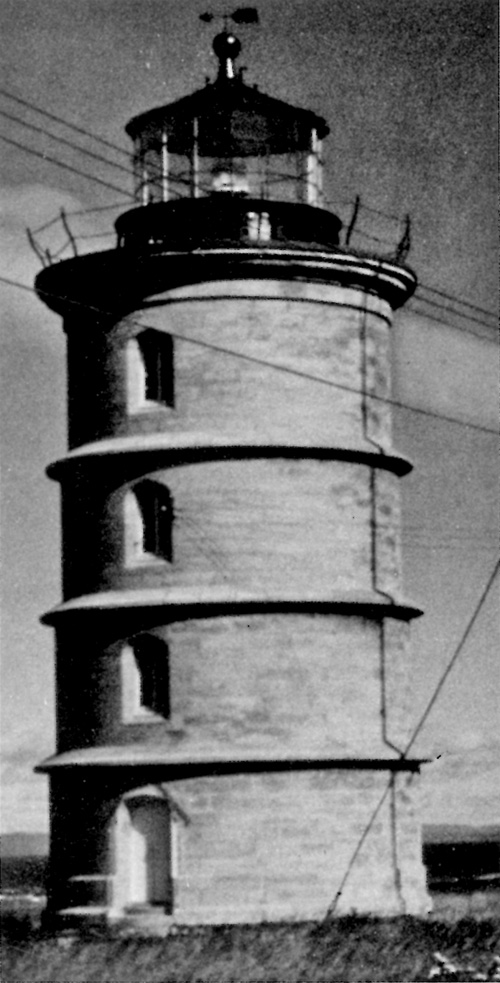

The 62-foot stone tower was one of four undertaken simultaneously by

the Canadian commissioners of Public Works. The stone was faced

externally with firebrick of a light colour. The solidly built circular

tower and lantern may still be seen at this lonely spot basically as it

was in 1858, although no doubt the firebrick has been renewed and

replaced several times. The first light was a fixed one fitted with

dioptric apparatus of the 1st Order.3 In the photograph in

Figure 38, the aerial for the radio installations, put up at a much

later date, is visible on the left.

37 Belle Isle lighthouse, north end.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

38 Belle Isle, south end, upper lighthouse.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

39 Belle Isle, south end, lower lighthouse.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

In 1880 this lighthouse was joined by a companion, to be known as the

"lower light." As may be seen from Figure 39, the circular lantern was

mounted directly on the stone foundation near the edge of a cliff 125

feet above the sea. The lower light was fitted with dioptric apparatus

of the 2d Order, to serve in conjunction with the "upper light."

A third lighthouse was built at the north end of Belle Isle in 1905.

This 90-foot cylindrical iron tower was later reinforced with concrete

and exterior supporting buttresses. The lantern was fitted with dioptric

apparatus of the 2d Order, employing a kerosene pressure lamp with a

50-mm. mantle.4 This light went into service with the opening

of navigation in 1905, in time for the new 17-knot Allan liners

Virginian and Victorian, to be joined during the season of

1906 by the celebrated CPR liners, the Empress of Britain and her

ill-fated sister, the Empress of Ireland. Until the construction

of the Triple Island lighthouse on the Pacific coast, the lighthouse on

the northern end of Belle Isle was the most northerly in Canada.

All three Belle Isle lighthouses are basically in their original

state today, although only the two at the south end of the island are

old enough to be of historical interest.

Point Amour

A very fine and impressive lighthouse which was built in 1857 at the

western entrance to the Strait of Belle Isle by the Canadian Board of

Works is still in good condition today. Situated on the bleak Labrador

shore, the Point Amour lighthouse, fully 109 feet in height, is a

particularly handsome structure. The slightly tapered circular tower was

built of stone, faced with firebrick and surmounted by a round lantern

mounted on a circular, railed lantern deck or

observation platform. Dioptric apparatus of the 2d Order signifies

the importance of this light at the western entrance to the

strait.5

The Point Amour lighthouse was the scene of a near disaster on the

afternoon of 16 September 1889 when a British naval vessel, HMS

Lily, went ashore in a dense fog. One officer and 30 of the crew

made shore. The lightkeeper, Thomas Wyatt, was credited with saving

four lives.6

40 Point Amour lighthouse.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Point Amour was one in a series of lighthouses built and maintained

by the Canadian government on the Newfoundland and Labrador shore to

serve ships on the St. Lawrence route. By the turn of the century Canada

maintained a total of 10 light stations in Newfoundland and

Labrador.7

|

| Belle isle (2) | Flower Island |

|

| Cape Bauld | Greenly Island |

|

| Cape Norman | Point Rich |

|

| Cape Race | Point Amour |

|

| Cape Ray |

|

|

With the exception of Cape Race, it will be noticed that all these

lighthouses were in the Strait of Belle Isle or along the west or gulf

coast of Newfoundland.

Bird Rocks

Construction of a lighthouse at the remote mid-gulf Bird Rocks

location, hard on the main fairway of shipping inbound from the Cabot

Strait, presented one of the most arduous projects attempted in Canadian

waters. As the department's chief engineer, John Page, commented in his

1860 report,

I beg to remark, that so far as my knowledge of the

place and locality goes, it appears to me that the construction of a

lighthouse on this islet will be one of the most difficult pieces of

work that has ever been undertaken by this

Department.8

A notation of the difficulties faced may be had from a glance at

Figures 41 and 42. Captain Bayfield, Admiralty hydrographer, had aptly

described these islets consisting of soft red sandstone or conglomerate

in his survey of the gulf some 30 years previously. The islets presented

near-perpendicular cliffs well over 100 feet in height on

every hand. Access to the top could be gained in only one or two

places, and that with no little difficulty; the device used by the

construction engineers is shown in Figure 42. Bayfield concluded by

stating that the landing of men and materials could only be effected in

the calmest of seas.9 The largest of the islets, and

presumably the one chosen for construction, was 1,800 feet in length by

300 in width, with sheer cliffs some 140 feet above the shingle. The

site could be approached only during the settled mid-summer months of

July and August.10 Carried out by contract let by the

Department of Public Works, the 51-foot timber and frame tower "of a

substantial description thoroughly bolted and fastened similar to the

one recently erected on Machias Seal Island" was completed in 1870 and

fitted with a powerful 2d Order lenticular light of French

make.11

41 Bird Rocks lighthouse in the middle of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

one of the most difficult construction sites.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

42 Landing stage and trestle used to move building material from the

shingle to the site, Bird Rocks Island.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

43 Bird Rocks lighthouse. This is a good example of the very short.

squat tower used on elevated locations.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Pointe-des-Monts

Based on the 1827 hydrographic survey conducted by Commander H. W.

Bayfield, R.N., Anticosti Island, the head of the Gaspé peninsula and

the broad reaches of the estuary became desirable sites for lighthouse

construction.12 According to surveys carried out at the

behest of the Lower Canada House of Assembly, a light at

Pointe-des-Monts on the north shore would benefit vessels both in- and

outbound, Anticosti Island, the scene of so many disasters, should have

lighthouses established at both its eastern and western extremities.

Cap-des-Rosiers, at the head of the Gaspé peninsula, would also be a

desirable location, but Bayfield considered that this could be dispensed

with if a lighthouse were built at the eastern end (Heath Point) of

Anticosti. He offered the further opinion that the Green Island light

would have been more effective on the neighbouring Red Islet, but that

it was not worthwhile to move it. Bicquette Island was another

favourable site, but because of its relative propinquity to Green

Island, this project might be considered less urgent.13

44 Pointe-des-Monts lighthouse.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

The crying need for lighthouses on the St. Lawrence in 1828 was

further emphasized by Captain Edward Boxer of HMS Hussar who had

been engaged in survey work along its shores.

I found the greatest

want of them, the navigation being so very dangerous, from the currents

being so very strong and irregular, and the very great difficulty in

getting good observations, the horizon at all times being subject to so

great an elevation and depression, and there not being even one in the

whole Gulph.

It was truly lamentable Sir, the number of wrecks we saw on the

different parts of the coast: . . . for the number of lives lost must be

very great, and property incalculable.14

Admiral Sir Charles Ogle was yet more emphatic in his description of

the hazards encountered along the coast for the want of lights.

The shores of Newfoundland, Anticosti, and the continent, are covered with

wrecks, occasioned chiefly by the want of Lighthouses, and the longitude

of the places being incorrectly laid down on the charts, and in the

books; under these circumstances I venture to recommend to your

Excellency, that Lighthouses should be erected on some of the principal

points — perhaps on St. Paul's Island, east end of Anticosti, Cape

Rosier, and Cape Deamon, which I conceive might be kept up by a Tax

levied on all ships entering the St. Lawrence, or the adjacent ports,

and would be cheerfully paid by the Shipowners who reap the

advantage.15

In the main, Ogle's recommendations concurred with Bayfield's except

that Bayfield preferred Cape Gaspé to Cap-des-Rosiers, and West Point of

Anticosti Island to Southwest Point on the basis that the former would

be visible from more points of the compass. But he feared that Lower

Canada would lack the money for so extensive a program.16

It was true enough that lack of money had put off necessary

lighthouse construction for a number of years, but in the 1828-29 session,

the Lower Canada legislature appropriated the sum of £12,000 for

this purpose. The total appropriation in 1831 reached £25,212 10s.

0d. local currency.17 The special committee on lighthouses

appointed by the House of Assembly selected the east and west points of

Anticosti Island and Pointe-des-Monts as sites; they further resolved to

contribute toward the building of lighthouses on St. Paul Island and

Cape Ray, two points vital to the navigation of the Cabot Strait giving

access to the gulf. These projects had to wait the concurrence of the

maritime colonies.18

The Pointe-des-Monts site had already been selected by the Quebec

Trinity House in 1826 as a good location to serve as a point of

departure for outbound vessels in order that they keep well clear of

Anticosti Island and as a checkpoint for inbound shipping. The Trinity

House board concluded its recommendations to the governor that the

utility of a light at Pointe-des-Monts was supported by "all Masters of

Vessels trading to this Country."19

The original Pointe-des-Monts lighthouse, a 90-foot circular stone

tower, has been replaced in recent years with a skeleton steel tower of

contemporary design, though the stone tower is still standing and

reported in good shape. The first lighthouse. completed in 1830, had

walls six feet thick at the base, tapering to two feet at the lantern

deck.20 The polygonal copper lantern was of the same

dimensions as that installed at Green Island, measuring 10 feet 6

inches in diameter and 6 feet in height. It was fitted with glazing

of "polished Plate Glass of double substance as made for the use of

lighthouses."21 The catoptric light consisted of 13 Argand

burners of brass fitted with copper tubes and "thirteen improved strong

Silver plated, high polished parabola reflectors on improved

principles," the estimate for the whole lantern assembly coming to

£960.22 Unfortunately, as is so often the case, this

estimate was very much on the low side, the final bill being

£1,766 3s. 6d.23 This handsome structure (see

Fig. 44) stood sentinel at this point for more than a century. The

original optic was replaced with a more effective lenticular apparatus

sometime in the eighties or nineties or after the turn of the

century.

Anticosti Island

The next lighthouse to be built in this region was that on Southwest

Point of Anticosti Island, guarding the approaches of the broad estuary

from the gulf. Originally Captain Bayfield had favoured West Point, but

on consideration, Southwest Point offered the twin advantages of closer

proximity to the shipping lanes and suitable building materials

(limestone and sand) were available on the site.24 The

75-foot lighthouse of stone construction went into service in 1831, the

first on Canadian shores to display a revolving light. The annual upkeep

of this lighthouse was estimated at £525, a figure which included

the cost of 600 gallons of sperm oil for the light at the rate of 10

shillings per gallon. The keeper was paid £130 per annum. The

tower, 36 feet in diameter at the base, was completed by the contractor

for the sum of £3,350 local currency and the lantern with the

optic was supplied for £2,800. The revolving light swept the

horizon from a height of 100 feet above high water with a range of 15

miles.25

A second lighthouse at the eastern extremity of Anticosti Island was

established in 1835, and a third on English Head in 1858 at the western

extremity. This 109-foot circular stone tower on West Point was

constructed under the aegis of the Canadian Department of Public Works.

Completed in 1858, the West Point lighthouse was of similar dimensions,

design and apparatus to the Point Amour installation, but unlike the

latter, the West Point structure was replaced in 1967.

None of this trio has survived to the present; indeed of all those

cited so far, only the Green Island and Pointe-des-Monts lighthouses are

extant today.

45 Cap Chat lighthouse, short tower with attached dwelling. Short

towers are often sited on lofty headlands where the light is already at

a considerable elevation above the sea.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

46 Anticosti Island, Southwest Point.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Point Escuminac

in 1841, the New Brunswick lighthouse commissioners established an

important coastal light at Point Escuminac at the northern entrance to

the Northumberland Strait. A quarter-century later a twin sentinel

joined it on the North Point of Prince Edward Island, on the opposite

shore. Described as an octagonal wooden building 58 feet in height, the

focal plane of its fixed light shone 78 feet above the sea and was

visible 14 miles in clear weather.26 A measure of the

importance of the Point Escuminac light to ships entering or leaving the

Northumberland Strait was its subsequent equipment with a lenticular

light of the 3rd Order. The old lighthouse was

replaced with a steel tower installation in 1963.

Miscou Island

Another fine old lighthouse, largely built of hand-hewn timbers, 80

feet in height and eight-sided, was constructed under the authority of

the Quebec Trinity House on Miscou Island in 1856. This one has survived

to the present and is said to be in good condition. Eventually it, too,

was fitted with a powerful dioptric light of the 3rd Order, and early

this century, with a diaphone fog alarm. Situated off Birch Point, the

Miscou Island light is a major coastal aid standing at the southern

entrance to Chaleur Bay.27

Point Prim

The oldest lighthouse to grace the verdant shores of Prince Edward

Island, Point Prim, built in 1846 and still in service today, stands

sentinel at the southern end of Hillsborough Bay on the outer approaches

to Charlottetown Harbour. The 60-foot circular brick tower topped by a

polygonal lantern is still in its original condition, complete with a

central weight shaft dating from the days of mechanically actuated

rotary mechanisms. This feature is simply a relic of the past, for the

light source and rotary machinery has long since been electrified. The

Point Prim lighthouse is now fully automated, in common with an ever

increasing number of lights. The lantern platform is gained by four

flights of stairs. Apart from the mercury vapour electric light source

and the lantern platform railing, the Point Prim light and optic are the

original installation. It is quite a handsome structure on a commanding

site, and one of the showplaces of the island.

47 Mark Point lighthouse, New Brunswick.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

48 Blockhouse Point lighthouse, near Chatlottesown, P.E.I.

(Photo by author.)

|

49 West Point lighthouse, P.E.I.

(Photo by author.)

|

Cap-des-Rosiers

The Cap-des-Rosiers lighthouse, completed in 1858 on Gaspé Cape, is

the fourth in the handsome series of Public Works lighthouses and today

is considered the showpiece of the Quebec agency. One hundred twelve

feet in height, its circular lantern housed a 1st Order dioptric light,

indicative that the Cap-des-Rosiers installation was considered a major

coastal light.

Fortunately the journals of the Canadian legislature record considerable

detail on this lighthouse, which is shortly to be removed from service.

The foundation, set 50 feet back from the cliff edge, extended 8 feet

below the surface. The masonry walls of the 112-foot tower tapered from

a thickness of 7 feet 3 inches at the base to an even 3 feet at the top;

similarly, the base diameter narrowed from 25-1/2 feet at ground level

to only 17 feet at the lantern platform. The tower contained nine

storeys including a basement and the light room directly below the

lantern. Windows were set at each storey or landing in an alternate

pattern.28

The masonry called for was of top quality. To

consist generally of good sized, flat, well-shaped stones, not less than

5 inches in thickness, laid on their natural and broadest beds in full

mortar, properly bonded over and with each other throughout the wall,

and to have their inner faces hammered or scrabbled off to a line

corresponding to the position they are to occupy in the work, one third

of the arch of each course to be laid as headers, that is to say: To

have their greatest length extending into the wall, the depth of these

headers for the first 30 feet in height of the Tower to be at least

3-1/2 feet, for the next 30 feet in height to be not less than 3 feet in

depth, thence upwards they may be from 2 feet 9 inches to 2 feet in

depth midway between the headers of the inner face, must be other of a

like length extending inwards from the exterior brick facing, especially

in the lower 50 feet of the building.

All the brick used in the exterior of the work to be of the best

quality of English Fire Brick laid throughout in horizontal courses,

except arches in English bond well flushed up at every course with

mortar. The brick facings of the Tower as before stated is to be one

brick (or 9 inches) in depth, with headers extending into the wall at

every fourth or fifth course.29

The windows were to be arched with stone, and the door with stone on

the inside and brick on the exterior. There were to be two doors to the

tower, the outer of which was to be 7 feet by 3 feet.30 The

exterior was to receive three coats of white lead and oil paint; the

interior surface of the walls was to be finished with two coats of

plaster.

It is not surprising that so carefully and soundly built a structure

should have lasted over a century and still be reported in excellent

condition. In the near future the Cap-des-Rosiers lighthouse may be

offered to the crown for possible preservation, since a light is no

longer needed at this point. It is a handsome and impressive structure,

somewhat similar in form and design to the series built on Lake Huron

and Georgian Bay at the same time. Cap-des-Rosiers is readily accessible

by motor, in contrast to Belle Isle or Point Amour, for which the

services of a helicopter or supply vessel would be required.

50 Plan drawings of the Cap-des-Rosiers lighthouse on the Gaspé

coast.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

51 Cap-des Rosiers lighthouse as it was.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Father Point

Transatlantic travellers of a few years ago, when the steamship lines

retained more custom, will remember Father Point some 180 miles below

Quebec where the pilot was dropped on the outbound voyage. The first

lighthouse at Father Point, according to the light lists, was put in

service in 1859, although one rather obscure source under the signature

of a Raoul Lachance speaks as early as 1800 of a lantern on the roof of

a house 45 feet in height, the light consisting of five oil lamps fitted

with 21-inch reflectors.31 The first lighthouse cited in the

light lists (Admiralty 1864) is described simply as octagonal with the

focal plane of the light 43 feet above high water. This lighthouse was

destroyed by fire on 13 April 1867; plans were at once set afoot for its

replacement at an estimated cost of $1,600 to $2,000.32 This

lighthouse in turn was replaced with a 97-foot, eight-sided reinforced

concrete tower in 1909 in order that a more powerful light and hence

larger lantern might be installed. The Father Point lighthouse was

fitted with external buttresses in similar manner to that at the north

end of Belle Isle. As a major coastal light Father Point rated dioptric

apparatus of the 3rd Order, manufactured by the Parisian firm of Barbier

and Turenne. It is understood that this optic with a mercury vapour

light is still in service at Father Point.

Green Island

The first lighthouse built on the shores of the St. Lawrence and

still standing today was that on Green Island in 1809. This is the third

oldest lighthouse in Canada, being pre-dated only by the Sambro light

off Halifax, and Gibraltar Point, no longer in use, on Toronto

Island.

As early as 1787 one Peter Fraser, who had been working 15 years for

the improvement of St. Lawrence navigation, went to London to raise

funds among city merchants trading to Canada. Fraser estimated that fully

8,000 tons of shipping passed Green Island off the mouth of the Saguenay

River in the course of a year. A light duty of 9d. per ton would finance

the Green Island project.33 Fraser's recommendation was

supported by Commodore Sawyer, R.N., in a report written aboard the

Leander in the harbour of Quebec, 9 October 1787.

I have seen the estimates and the plan of a lighthouse meant to be

erected on Green Island; also the plan of a Dwelling House. In regard to

the expediency of the former, I am clearly of opinion that it is

absolutely necessary as I look upon that part of the River to be most

dangerous owing to the situation of Red Island, and the setting of the

Currents from the Saguenay River, which are so very irregular that

Vessels are frequently deceived as to their Situation, and I am credibly

informed that several have been Ship wrecked on Red Island, that would

have been saved if there had been a light on Green

Island.34

But it was not until the spring of 1806, more than 18 years later,

that the executive council of Lower Canada took the matter in hand. By

late November of that same year, the masonry work on the 56-foot

circular stone tower was finished. A further sum of £875 local

currency was needed in addition to the original £500 grant to

complete the project. The lantern was supplied by George Robinson of

London, and the lamps and reflectors by the London firm of Brickwood and

Daniel at a cost of £388 sterling. The stone tower was topped by a

double flooring of three-inch oak plank sheathed with copper, on which

was mounted the lantern.35

An early inspection by the deputy master of the Quebec Trinity House

on the night of 13 September 1810 found all in good order.

We arrived at half past two o'clock in the morning of Thursday the

thirteenth instant, and found the lantern illuminated with thirteen

lamps, set in an equal number of reflectors, these with the other

apparatus in it were in high order. At day-light, we again examined the

lantern and tower; the former's erected in a master-like solid manner,

the latter is also a piece of good mason-work. The rough casting

particularly attracted our notice, it being exceedingly hard and

durable.36

The first keeper of the Green Island lighthouse was Charles

Hambledon, who was instructed to be in continuous attendance from 15

April to 15 December. His duties included the care of the lamps,

reflectors and the lantern glazing, for which he was paid £100 per

annum. The keeper must be "careful, sober and intelligent."37

He was required to keep a daily journal, "of all occurrences and

observations" to be forwarded to Quebec once a quarter.38

Late in 1811, the following supplies were ordered for the Green

Island lighthouse:

2 caldrons of coal

20 lbs. soap for washing

polishing leather and cloths (for the reflectors of polished silver)

1000 board nails

100 boards

1 lb. polishing powder for the reflectors

24 gross fine cotton wick for the lamps39

The Green Island structure remained the sole light on the

shores of the mighty river for a full 21 years.

Stone Pillar and Red Islet

The 1840s saw the establishment of three lighthouses below Quebec.

Two of these, Stone Pillar and Red Islet, were of similar

design—circular, grey stone towers, each 52 feet high with circular

lanterns. A distinctive feature of these two towers was the three string

courses spaced at equidistant intervals, mainly a decorative

embellishment. The Stone Pillar lighthouse was built in 1843, and the

Red Islet structure in 1848. According to local authority, stone for the

latter was brought out from Scotland. Both lighthouses are standing

today.40 As recently as 1966 the Red Islet light was

described as catoptric long focus. of which there must be very few left

in service.

52 Red Islet lighthouse, built in 1846. The stone for this lighthouse

is said to have been brought out from Scotland.

(Canada. Department of Transport.)

|

Bicquette Island

The third of this trio and farthest downstream of the three was

Bicquette Island, built in 1843 by the Quebec Trinity House in the

broadening reaches of the river below Quebec. Shipowners and mariners

had been petitioning for a light at this point as early as 1828.

It frequently happens that vessels running up in a dark night give

to the Island of Bicquet so wide a birth that the North Shore of

Portneuf or Mille Vaches will frequently bring them up. Vessels

navigating the River St. Lawrence are never certain of their distances,

for where the channel is very narrow and the current strong without any

safe anchorage ground, vessels are often at a loss which course to steer

to a place of safety. A Light House upon Bicquet Island would in such a

case prove of great advantage, inasmuch as a vessel would then make

boldly towards the light, knowing that from thence she could direct her

course for Green Island, and if the weather was clear she would possess

the further advantage of obtaining a view of one Light while losing

sight of the other.41

Sir John Barrow, secretary to the commissioners of the Admiralty,

recommended in 1838 the installation of a strong light on Bicquette

Island, but with a characteristic to distinguish it from the fixed light

on Green Island.42 The Quebec Trinity House, on the other

hand, expressed a preference for closely adjacent Bic Island on

the grounds that fuel and fresh water were more readily available;

but in the sequel, Bicquette Island was the

chosen site. Construction estimates stood at a minimum

£6,000.43 The circular stone tower 74 feet in height

was completed with a revolving light in 1844. The first fog alarm was a

gun, to be fired hourly in thick weather. The Bicquette lighthouse is

another survivor from the colonial past. It is understood that the fog

signal gun is still on the site, though replaced by more effective

devices many years ago.

This construction in the 1840s notwithstanding, at mid-century the

words of Beaufort's report to the Admiralty prepared in 1834 were still

basically true,

Thus in a seaboard of about 400 leagues, as there are

at present 20 lights, or an average one to about every 20 leagues, very

few more can be wanted for the general purposes of navigation — but

those few would be of most essential benefit.44

These were to be forthcoming in the next few decades.

|