|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 19

Yukon Transportation: A History

by Gordon Bennett

The Dawning of a New Era

I

Apart from such strategically inspired transportation projects as the

Alaska Highway and Canol, very little in the way of local

transportation development took place between 1939 and 1945. Road work, with

a few minor exceptions, was confined to maintenance and improvement. In

1941 the Whitehorse airport was completely rebuilt and transformed into

a "1st class" facility as part of the Northwest Staging Route, but

Whitehorse's emergence as a major air centre was largely the result of

the American military presence, a factor wholly unrelated to local

economic conditions. The aerial division of the White Pass and Yukon

Route, British Yukon Aviation, was sold to Canadian Pacific Airways in

September 1941, the sale marking an important departure from the White

Pass and Yukon Route's policy of involving itself in all aspects of

Yukon transportation.1

The territorial mining industry escaped the full economic impact of

the war until 1943. Indeed, mineral production for each year between

1937 and 1942 exceeded in value that of any year after 1917. Although

the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation encountered "some difficulty in

obtaining necessary operating parts and material" in 1941, the small

production decline recorded for that year was largely attributable to a

labour strike and the driest season on record. By 1943, however, the

drain on the labour pool caused by enlistments and the absorption of men

into wartime construction projects had reached serious proportions.

According to the president of the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation,

"labour available for 1943 [was] approximately 30% of the amount

required for full-scale operations." As a consequence, gold production

fell abruptly, from 83,246 fine ounces in 1942 to 41,160 fine ounces,

23,81.8 fine ounces and 31,721 fine ounces between 1943 and 1945

respectively.2

Not too surprisingly, this decline had no discernible impact on the

territorial transportation system. The intensive utilization of existing

transportation facilities by the military was a mitigating factor, as

was the reorganization of the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation in the

early 1930s which had created a mature regional economy based on placer

mining. This economy was not dependent on new gold discoveries but on

the reworking of known reserves with more efficient procedures. Local

transportation needs such as roads were already in existence. The

remaining transportation requirement, access to Whitehorse, was

furnished by the British Yukon Navigation Company in summer and by air

during the closed season of navigation. Unlike the Mayo district, where

transportation was directly dependent on production because of lode

mining, the transportation facilities serving Dawson from Whitehorse

were dependent on the market for consumer goods. Since the population of

the Dawson area remained relatively constant throughout the war, this

service was not disrupted.3

Of far greater import to the territorial transportation system was

the suspension of operations by Treadwell Yukon in November 1941. The

collapse of the silver-lead industry brought on by the depletion of

known ore reserves dealt what was tantamount to a terminal blow to river

transport which for 20 years had been sustained by Mayo district ore

shipments. Between 1939 and 1946, the only years for which tonnage

statistics covering the period are available, the total freight tonnage

handled by the British Yukon Navigation Company in Canada declined by

almost 50 per cent as a result of the fall in silver-lead

production.4

II

In the immediate postwar period a lively debate took place over the

future course of Yukon transportation development. George Black, in a

speech before the House of Commons, declared that the "Yukon's greatest

need today is for roads. Without roads there can be no advance. In some

districts . . . development is at a standstill for lack of roads." The

federal government, on the other hand, no doubt a trifle wary at the

prospect of another Alaska Highway, regarded road construction coolly

and showed a strong inclination toward aviation

improvements.5

Local clamour focused specifically on the demand for an all-weather

road between Whitehorse, Mayo and Dawson. The resumption of large-scale

silver-lead mining in 1946 after an hiatus of four years lent this

demand a degree of urgency and resulted in a request from the Keno Hill

Mining Company, Treadwell Yukon's successor, for the immediate

construction of the Whitehorse-Mayo section of the proposed

Whitehorse-Mayo-Dawson road. With national priorities geared to the

provision of housing for returned servicemen and the conversion of

industry to a peacetime footing, the Whitehorse-Mayo road found little

support in Ottawa and the request was shelved by the Department of Mines

and Resources.6

The dilemma facing the silver-lead industry approached crisis

proportions in 1947 when a substantial portion of the year's production

failed to reach market for want of transportation. The failure disrupted

plans to expand the Keno Hill Mining Company's operation and helped to

underline the fundamental inadequacies of river transport. So long as

the industry remained dependent on water transport, the vintage

complaint (1929) that output could be "materially increased, but when

the White Pass can only handle a certain tonnage each year, there is no

advantage in increasing output beyond that figure would remain. The

existing transportation system was also a major factor in the high

operating costs incurred by the industry because of primitive handling

facilities at transhipment points, the number of transhipments required

and the seasonal nature of navigation. As well, the reduction in Stewart

River traffic that followed the closing of the Treadwell mines in 1941

had allowed the main navigation channel to fill with sediment with the

result that postwar transport on the Stewart was adversely

affected.7

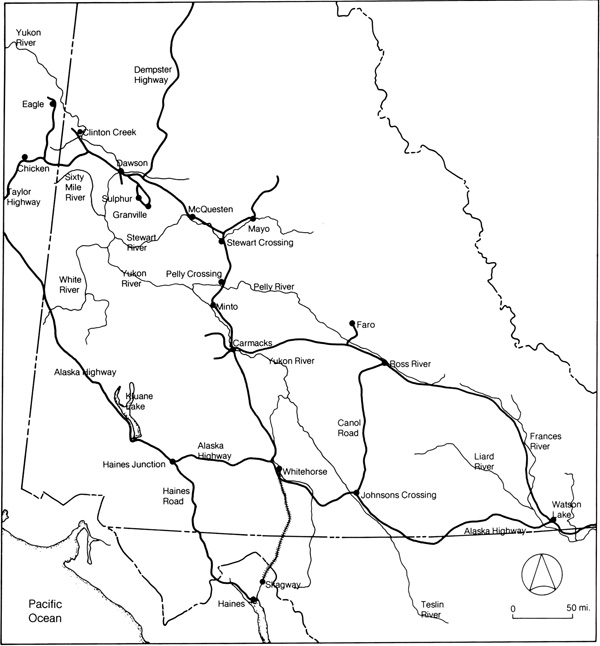

131 Post-1945 road system.

(Map by S. Epps.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

The 1947 crisis forced a reconsideration of the Department of Mines

and Resources's territorial roads policy and acted as the catalyst for

the Whitehorse-Mayo road. In January 1948 the department gave its

approval to an all-weather truck road between the two centres. The

246-mile highway was completed in October 1950 and spelled the end of

navigation on the Stewart River. Although it required a large initial

investment and involved higher direct costs, the highway more than paid

for itself by increasing the shipping season from four and one-half to

ten months. All-season ore transport was not obtained until the early

1960s when steel bridges replaced ferries and ice bridges over the main

river crossings.8

The extension of the shipping season had an immediate impact on the

silver-lead industry and illustrated an interesting paradox; that cheap

transportation, such as that provided by the sternwheeler, did not

necessarily constitute the most economical form of transportation over

the long run. Ore production for 1950 more than doubled that of 1949 and

doubled again in 1953, an increase in volume that was in part

attributable to the highway's construction and which more than

compensated for the initial high cost of road transport.9

Road transport was instrumental in reducing the indirect costs of

production, moreover, by releasing large amounts of capital previously

tied up in inventories. This, combined with the elimination of the

traditional holdover period associated with seasonal transportation

wherein ore mined in one year did not realize a return until the year

following, enhanced the industry's prospects and facilitated the

refinancing of the Keno Hill Mining Company and its reorganization as

United Keno Hill Mines in 1948.10 Given the particular nature

of the silver-lead market, the elimination of the holdover period was a

great boon. By extracting and marketing in the same year, producers were

placed in a more advantageous market position and were able to avoid a

repetition of the 1949 experience, when the industry lost some $130,000

on its 1948 production as a direct result of a decline in silver-lead

prices.11

Ironically, the federal government acquired the British Yukon

Navigation Company's Marsh Lake dam, rebuilt it at a cost of $125,000,

and agreed to operate and maintain it at the very time (1948) that its

reformulated road programme was in the process of rendering water

transport obsolete. In 1949, in an attempt to reduce operating costs,

the British Yukon Navigation Company installed a coal-fueled boiler

system in the SS Whitehorse, but the "adaption in grates was not

the most efficient possible" and the steamer was converted back to a

wood burner. By 1950 the company's sternwheeler operation had been

reduced to one trip every ten days to Dawson, occasional downriver runs

to Alaska and tourist excursions on Tagish Lake.12

III

When the Overland Trail fell into disuse after 1937 Dawson was

deprived of its only overland connection with an all-weather

transportation centre. The location of the Alaska Highway and the

federal government's postwar roads policy added to a growing sense of

isolation evident in the community and served to focus attention on the

need for improved communication. This need was given a strong impetus by

the realization that overland transport was becoming an increasingly

important factor in territorial transportation.

Failure by the Department of Mines and Resources to counsel a

Dawson-Whitehorse road was partially ameliorated by the possibility of

linking Dawson with the Taylor Highway in Alaska. Construction of this

highway between Tok Junction on the Alaska Highway and Eagle, Alaska,

began shortly after the war. By 1948 the road had been completed as far

as Chicken, Alaska, 20-some miles from Poker Creek, the Canadian

terminus of the Sixty Mile road which ran west of Dawson. As the special

commissioner of the Northwest Highway System observed, "it appears that

a little more construction and some betterment on the Alaska side of the

border could result in Dawson City having an all-year-round access to

the Alaska Highway at Tok."13

Access to the Alaska Highway by way of Chicken and a corollary scheme

to supply the Dawson area from the port of Valdez, Alaska, met stiff

opposition from the White Pass and Yukon Route which saw in the proposed

Sixty Mile road extension and the opening up of the port of Valdez a

threat to its monopoly on transportation to and from the Dawson region.

More importantly, the scheme presented a challenge to Whitehorse's

traditional function as the territory's supply centre and distributing

point. Despite strong support for the scheme in areas adjacent to

Dawson, the Sixty Mile road extension, which entailed very little in the

way of new construction, was not completed until 1951. In the

meantime, a winter trail connecting Dawson with Stewart Crossing on the

Whitehorse-Mayo highway had been built in 1950.14 This diminished to a

large extent the need for developing the Sixty Mile-Taylor Highway

access to the Alaska Highway. Since the Sixty Mile extension was opened

to traffic during the summer months only, it failed to develop as an

important commercial artery for it could not compete with the

Whitehorse-based British Yukon Navigation Company.15 The

absence of an all-season overland link between Dawson and Whitehorse was

finally remedied when the federal government decided to build an

all-weather road between Dawson and Stewart Crossing in 1951.

Construction of this 120-mile road was begun in 1952 and completed in

1955.16

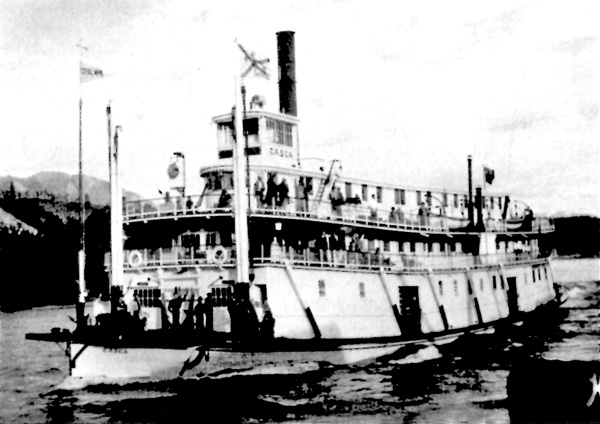

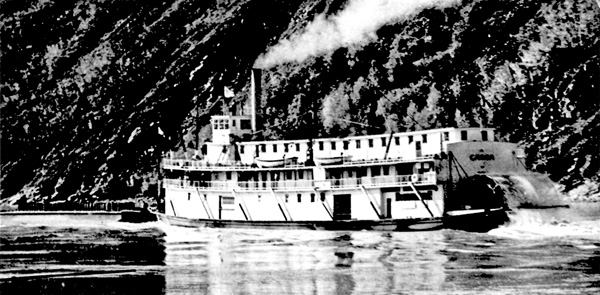

132-134 "Casca" graced the nameplate of three

upper river steamers. 132, Casca No. 1 built in 1898, was

dismantled in 1911. (Yukon

Archives.) 133, Casca No. 2,

with concealed braces, was built in Whitehorse in 1911 and wrecked in

1936. (Photo by W. Bamford.) 134, Casca No. 3 was launched in

1937, retired in 1952 and destroyed by fire in 1974. (Yukon Archives.)

|

IV

The decade 1946-55 was one of great change in the territorial

transportation system. The transition from water to overland forms of

transport, begun with the construction of the Whitehorse-Mayo highway

and completed with the construction of the Dawson-Stewart Crossing

road, was but one of these changes. No less important was the remarkable

reversal in the economic fortunes of the White Pass and Yukon Route.

These fortunes, which entered a period of protracted decline at the

time of the First World War, dropped to a low ebb during World War II

with the suspension of production by Treadwell Yukon and the transfer of

the railroad to the United States Army. When the railroad was returned

to the company on 1 May 1946 following cancellation of the army lease,

the company was, in the words of one official, "very near to the end."17

While the White Pass and Yukon Route has since made much of the claim

that the army left the railroad "in a virtually tumbledown condition"

and "did not pay . . . much rent," the army can not be held responsible

for the difficulties which beset the company after 1946.18 Instead, the

company's postwar plight should be seen as the climax of years of

neglect. By 1950 the unpaid interest on the company's debentures had

grown to $2,458,000, while dividends, the lifeblood of any successful

enterprise, had not been paid since 1912. Although the company did

manage to show a nominal book profit, this was achieved at the expense

of necessary maintenance and repair work, an expedient that might have

been justified over the short term, but which, because of local economic

conditions and foreign control, had become a long-term characteristic of

the operation.19

Just as the company appeared to be slipping into the morass of

insolvency, an English financier by the name of Norman D'Arcy, backed by

the Hambros Bank, quietly acquired all the bonds, debentures and stocks

of the White Pass and Yukon Route. On the

advice of C.D. Howe, minister of Trade and Commerce, D'Arcy formed a new

Canadian corporation in 1951, the White Pass and Yukon Corporation, and

installed Frank H. Brown as president. To finance the takeover, the new

company sold 3.7 million dollars worth of bonds on the London

market.20

A basic shift in managerial outlook followed the company's

reorganization. Whereas the company had previously been forced to

temporize in semipermanent fashion with a multitude of difficulties,

the new corporation undertook an ambitious programme which had as its

goal the elimination of problems at the source. This new outlook was

given cogent expression by Frank Brown at the company's 1953 annual

meeting. Operating on the assumption that "all Canadian railways face

the same problem of low earnings through the high cost of running long

distances through sparsely settled country," Brown concluded that

"modernization and mechanization to the fullest practicable extent and a

firm determination that each subsection of operations shall pay its own

way" was the key to extracting the company from its moribund

state.21

Modernization proceeded rapidly under Brown's stewardship. New

rolling stock was acquired, heavier rail was laid down and obsolete

equipment and buildings were sold or written off. To avoid backtracking,

the railway repair shops at Skagway were relocated, new ones were built

and at Whitehorse the roundhouse was remodelled. For the first time in

decades the company's physical assets were adequately insured. Beginning

in 1954 the company gradually replaced its steam locomotives with

specially designed diesels capable of operating under conditions of

extreme temperature (from 95°F above zero to 65°F below zero).

As early as 1955 Brown was able to report that the diesels "fully

measured up to expectations." Far more efficient than the conventional

steam engine, diesel-powered locomotives effected an immediate 60 per

cent reduction in fuel costs and increased hauling capacity by a

corresponding amount. Additionally, they were easier to maintain and did

less damage to the permanent way. By 1963 diesel conversion was complete

and the steam engine, once the proud workhorse of the White Pass and

Yukon Route's transportation system, joined the sternwheeler in

retirement.22

The disappearance of the river boat preceded that of the steam engine

by seven years and perhaps more than anything else signified the

passing of an era in Yukon transportation. A fixture for 86 years, the

sternwheeler was the victim of Brown's "firm determination that each

subsection of operations shall pay its own way" and the new highways

that siphoned off the trade that had once been the sternwheelers

exclusive preserve.23 Before 1950, river and road transport

had been complementary; construction of roads had, in point of fact,

"meant more business for the sternwheelers, and also, a more varied

schedule."24 But the completion of the Whitehorse-Mayo

highway in 1950 and the Stewart Crossing-Dawson road in 1955 brought the

river and these highways into direct competition, a competition that

the river was fated to lose because of its seasonal nature and rigid

capacity.

In a last-ditch attempt to perpetuate the sternwheeler, the British

Yukon Navigation Company converted the ore-carrying SS Klondike

into a tourist vessel. Under an arrangement with Canadian Pacific

Airlines which chartered the Klondike to ferry passengers from

Whitehorse to Dawson, an extensive refurbishment was carried out during

1953-54. The dining room was enlarged, a new lounge and bar were

added, and the number of staterooms was increased (the fueling system

had been changed from wood to oil in 1951). In spite of these changes,

however, the experiment was not a success. Operational expenses exceeded

revenues and low water on the Yukon resulted in the cancellation of a

number of tours.25

On 18 August 1955 SS Klondike No. 2, the last sternwheeler on

the Yukon River, steamed into Dawson for the last time.26 The

following day it started on the return run to Whitehorse where it

shortly joined its fellow craft in permanent retirement, thus bringing

to a close one of the longest chapters in the history of the Yukon

territory.

Containerization was clearly the most important and unique aspect of

the modernization programme outlined by Brown in the White Pass and

Yukon Corporation's 1952 annual report.27 It evolved out of

the persistent problems created by breakages, shortages, loss of time

and general freight disorder, all of which contributed to the high

operating costs and economic malaise that plagued the

company.28 Company legend has it that the system was

developed in Archimedes' fashion "on the banks of the Yukon River near

Whitehorse by three worried White Passers sitting on a

log."29 Be that as it may, the decision to go ahead with

containerization transformed the Yukon transportation system, or at

least that portion of it under the White Pass and Yukon Corporation,

from one of 19th-century vintage into what was perhaps the most modern

in the world.

Because ship holds on the Vancouver-Skagway run were not suitable for

container handling, the White Pass and Yukon Corporation organized a

wholly owned subsidiary, British Yukon Ocean Services, in 1954. The

following year the company launched the first container ship in the

world, the four-thousand-ton Clifford J. Rogers.30

What distinguished the White Pass and Yukon Corporation's container

system from that of any other in existence was its integrated

character. The basic principle underlying the concept was "uniform

procedures and methods."31 Every aspect of the company's

transportation establishment was designed specifically for container

handling: the coastal vessel, the railroad and the highway trucking

division. The original containers, coloured variously to designed

merchandise, bulk loads, refrigerated products and explosives, measured

seven feet by eight feet by eight feet. Unitized pallets called trays

were used for ore transport. All freight handling at transhipment

points was done with straddle carriers or fork lifts and the ship was

equipped with a gantry crane.32

Since 1955 when the Container Route, as it is called, was inaugurated,

a number of refinements and improvements to the original system have

been effected. In 1965 the Clifford J. Rogers was retired and a

new container ship, the Frank H. Brown, was launched. To

accommodate the increased capacity of the Brown, the company

tripled the size of its containers to 25 feet 3 inches by 8 feet by 8

feet. As well, a "tear" or parabolic container was developed to handle

ore. In 1969 a second ship, the MV Klondike was placed in

service. To complete the modernization programme, a new Vancouver

terminal and the Skagway Bulk Storage and Loading Terminal were

built.33

Today the White Pass and Yukon Corporation operates at a

profit.34 This complete turnabout in the economic fortunes of the

enterprise is in large measure attributable to the implementation and

refinement of the integrated container system. That system has "lifted

White Pass from the doldrums as regards ratio of out profit to sales," a

recent presidential report has stated, "to a ratio more in keeping with

the ratios which prevail in the case of numerous successful Canadian

companies." Containerization has practically eliminated loss and

breakage, reduced paper work to a minimum, done away with expensive and

unnecessary handling and given the company a margin of operational

flexibility never before imagined.35

For the Yukon the benefits derived from the integrated container system

have been no less significant. The Container Route has meant faster and

more efficient service as well as substantial reductions in freight

rates.36 This last is of vital importance in view of the

territory's remoteness and its economic base.

V

A new manifestation of federal interest in the North occurred

coincidentally with the transportation changes initiated by the White Pass

and Yukon Corporation in the early 1950s. While federal

interest in the Yukon was certainly not a novel phenomenon, past

government activity had tended to be of a reactive and ad hoc nature.

What distinguished this new manifestation was that it became an

integral part of national policy.

Out of this qualitatively different government interest in the North

emerged the concept of "northern development." "It has been said,"

Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent told the House of Commons on 8 December

1953, "that Great Britain acquired her empire in a state of absence of

mind. Apparently we have administered these vast territories of the

north in an almost continuing state of absence of mind." To remedy this

situation, the government proposed reorganizing the Department of

Resources and Development and renaming it the Department of Northern

Affairs and National Resources. "We think that the new name is rather

important," the prime minister declared, "it is indicative of the fact

that the centre of gravity of the Department is being moved north." The

shift in thinking that accompanied the change in name was substantive.

For the first time in Canadian history a minister was charged "to

promote measures for further economic development" and "to develop

knowledge of the problems of the north and the means of dealing with

them."37 Northern development, fostered by the federal

government, was to become a reality.

A review of what has taken place since 1954 demonstrates clearly that

successive governments have tended to regard northern development in

terms of accretions to the transportation system. John Diefenbaker,

perhaps the archetypal advocate of northern development, has given this

understanding its clearest expression in stating that "transportation is

the key to the development of the North."38

More specifically, this emphasis on transportation has focused on road

construction, especially as northern development policy has been applied

in the Yukon.39 A significant departure from the post-1945

but pre-northern development policy of encouraging aviation, this

approach to northern development can be said to represent a vindication

of a half-century of agitation in the territory for new and better

roads.

The Diefenbaker government's "Development Road Programme," the

territorial adjunct of the more familiar "Roads to Resources

Programme," provided the first real impetus to "development" road

construction in the Yukon. The Roads to Resources Programme was

actually an amplification of a policy outlined by the previous Liberal

administration, under which the federal government agreed to pay the

entire cost of approved development roads. Development roads, as

distinct from conventional roads, were roads that were designed to serve

or to create a potential transportation market by opening up new areas for

exploitation and as such introduced an element of risk that had

previously been assiduously avoided.40 This fact was not lost on

critics of the policy, who pointed out that a development road could be

built for which traffic might never materialize. In practice, however,

the theoretical distinction between development roads and other roads

has not been so clear cut. Modern mining companies with an abundance of

new technologies relating to exploration, location and testing bear

little resemblance to turn-of-the-century gold companies, let alone the

individual prospector who scoured the creeks during the early days. As a

result, the risk factor has been largely anticipated during an earlier

phase of development. For this reason such northern development projects

as the Dempster Highway between Dawson and Fort McPherson or the

reopening of the Canol road between Johnsons Crossing and Ross River for

Anvil mines have not been inordinately high-risk ventures.

Although an important aspect of northern development policy has been the

recognition of the significance of transportation to expansion and the

federal government's obligation in fostering its development, it must be

noted that the central government participated in a number of Yukon

transportation projects long before the concept of northern development

was articulated. In varying degrees, road building as well as aids and

improvements to navigation were considered as falling within the proper

sphere of federal responsibility as early as 1900, as federal grants to

the territory for road construction and maintenance, and the work

performed by the Department of Public Works on navigable waterways bear

witness.41 These examples of participation, however, differed

from transportation projects undertaken for northern development

purposes in two respects. In the first place, they were designed to

serve existing, not potential, transportation needs and second, the

demonstration of an actual transportation need, as was the case after

the abandonment of the Overland Trail, provided no guarantee of federal

action.

VI

Despite efforts by the federal government to meet the increasing

territorial demand for roads, many regions of real or suspected economic

potential remain unserved by any form of transport other than the

airplane. This constitutes a major problem because most of these regions

require surface transport in order to be developed. Because the public

sector has neither the capacity nor a legitimate obligation to satisfy

this need, private enterprise has come to play an increasingly important

role on supplying ground access, usually in modified form, to remote

locations in which it has an exploitive interest.

An excellent example of this type of participation was the formation

of Arctic Oil Field Transport by the White Pass and Yukon Corporation

and the Proctor Construction Company of Whitehorse. The company was

organized to move supplies and heavy equipment to proposed drilling

sites in the Bell River area of the northern Yukon in the late 1950s.

Instead of employing the conventional technique of transporting freight

by tractor-drawn sleighs over roadless wilderness, the company decided

to build a winter truck trail over the snow between Elsa and the testing

site, 45 miles inside the Arctic Circle. Working from an aerial survey,

the company bulldozed a 385-mile road, known as the Wind River Trail,

during the winter of 1959-60 that was capable of handling large diesel

tractor units. Rivers were crossed with the aid of ice

bridges.42

The Wind River Trail was an ingenious expedient that satisfied the

immediate problem of short-term ground access into a remote region at

minimum cost. Within the brief period of five months Arctic Oil Field

Transport not only provided a serviceable freight route into an hitherto

inaccessible location (except for the 19th-century fur trade), but

completed its delivery schedule of three thousand tons.43

More importantly, the Wind River Trail showed that private enterprise

can and should accept some responsibility for the building of roads in

the Yukon, especially those of an exploratory and highly speculative

nature.

Another area in which the private sector has made an important

contribution has been in the development of vehicle technology. Before

1960 most of this technology was developed "south of 60," and the North

in general and the Yukon in particular were in direct beneficiaries.

This was especially true of railroads, sternwheelers, trucks and

tractors, most of which were imported with little or no modification.

Since 1960, however, private enterprise, in league with such

establishments as the Muskeg Research Institute at the University of New

Brunswick, has shown an increasing willingness to address itself to the

peculiar problems of northern transport and to develop vehicles

specifically designed for the northern environment.44

VII

Air transport continued to develop at a steady pace after 1945 and by

1957 an estimated seven hundred aircraft were in service in the

territory. The helicopter, which was substantially refined during the

war, was introduced during the late 1940s and proved a boon to

prospecting and exploration especially in rugged, unpopulated country

where mobility was crucial and where operations were confined to the

summer months. Other aviation improvements such as modern airports and

aircraft resulted in bush flying being rapidly superseded on the main

air routes although it continued to play an important role on the

frontier. In 1968 Canadian Pacific Airlines, the principal carrier

flying into the Yukon, inaugurated jet service between Vancouver and

Whitehorse and followed this by the establishment of jet service on the

Edmonton-Whitehorse run.45

Although air transport became an integral part of the Yukon

transportation system after 1945, it failed to escape the functional

limits which had been set for it during the prewar period. Except for

prospecting and exploration as well as passenger and lightweight,

high-revenue freight movement, traffic functions which the airplane

performed without serious competition, the airplane's role in the

territorial transportation system continued to be an auxiliary one.

Despite attempts by the federal government to foster aviation in the

immediate postwar period and the present-day efforts of critics of the

ground transport orientation of northern development, it appears

unlikely that the airplane will be responsible for a spectacular

breakthrough in the Yukon transportation problem.46 In an

area where cheap and efficient bulk transport remains the most

persistent need, the airplane's horizon is restricted.

|