|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 19

Yukon Transportation: A History

by Gordon Bennett

The Pattern Emerges

I

The Yukon is a land of paradox:

richly endowed and barren, enticing and forbidding. To some it

conjures visions of treasure untapped, a promise unfulfilled and a

future still to be realized; to others it symbolizes nothing more than

the "land that God gave as Cain." Ironically, neither view is without

validity, for what nature bestowed in munificence, geography conspired

to make inaccessible.

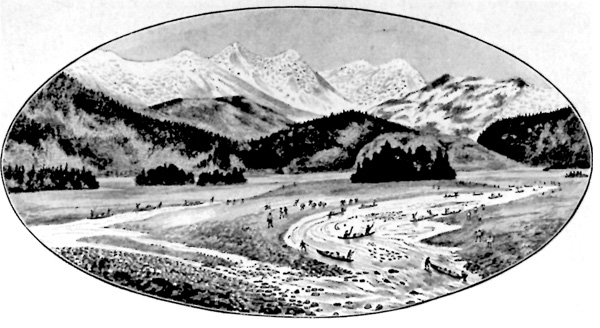

Situated in the northwest corner of North

America and separated by an ice-packed ocean, two seas and a

difficult overland and river route from Europe, the Yukon remained

untouched by European expansion until the mid-19th century. Surrounded

by a series of geographical barriers: the St. Elias Mountains and the

northern Cordilleras on the southwest, the Cassiar and Rocky mountains

to the south, the Mackenzie Mountains on the east and the Arctic Ocean

to the north, the Yukon presented a formidable prospect. For centuries

these natural obstacles effectively precluded immigration to the

interior. Only the Yukon River, which rises 15 miles from the Pacific

Ocean in northern British Columbia and runs two thousand miles through

the Yukon and Alaska to the Bering Sea, offered relatively easy entry;

yet even this fissure was a grudging concession, for the climate ensured

that the river would be closed to navigation for almost eight months of

the year and semiaridity helped to ensure that the river would

always be shallow during the open season of navigation. The low

temperatures and light precipitation were to make husbandry unfeasible.

Finally, most of the region escaped the scourge of glaciation, a fact

that for centuries preserved the ramparts and protected the resources

from man.

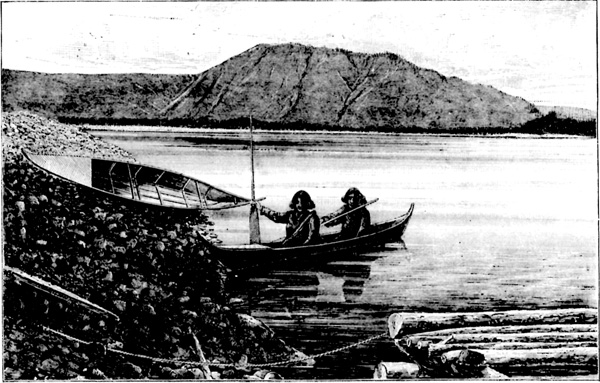

1, 2 Two types of canoes employed by Indians of the Fort Selkirk area.

(Frederick Schwatka, Along Alaska's Great River [New York: Cassell

& Company (1885)], pp. 221, 253.)

|

II

The white man was not the first to pierce the Yukon's natural

defences. The Indian preceded him by thousands of years, by way of the

land bridge that then permitted migration across the Bering

Strait.1 Little is known of these Indians and their way of

life before the arrival of the whites. After contact had been

established, native culture was evaluated from a technological

perspective and judged primitive. "Civilization," as understood by the

early explorers and traders at least, was unknown to the Indian. While

it is undeniable that the apparent simplicity of native culture was in

some measure shaped by geography and climate, these factors were not

primary for the white man ultimately shared the same region under the

same conditions and, if his culture was at best that of the frontier, it

was nonetheless technologically more advanced.

What distinguished the culture of the Russian and the European in the

North from that of the indigenous peoples were certain values on the

one hand and on the other the existence of a transportation

system which made possible provisioning and supply, as well as

communication, with the outside.

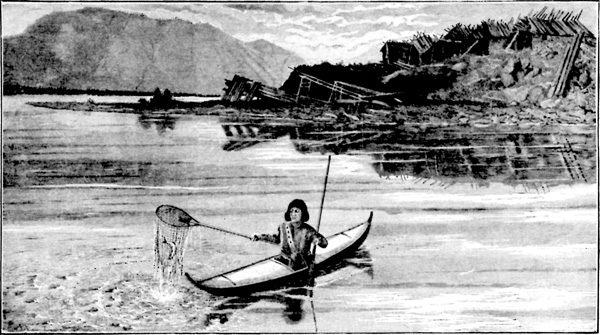

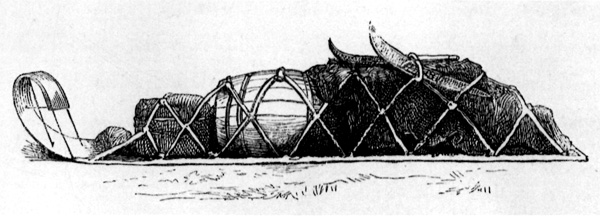

3 A sled used by the Indians of the lower Yukon River.

(W.H. Dall, The Yukon Territory [London: Downey, 1898], p. 166.)

|

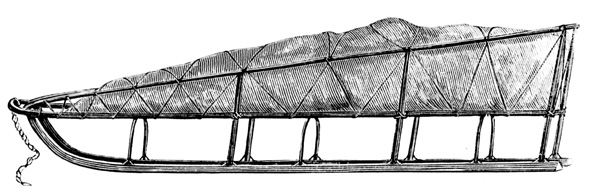

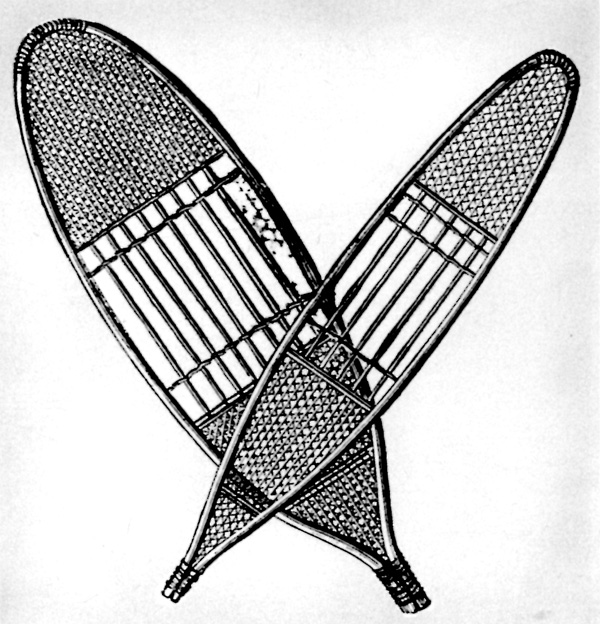

4, 5 various types of northern snow shoes. 4, A is an Eskimo or

Inuit type, except for the interstices and flat surface, it is similar

in design and size to B, the Hudson's Bay Company snow shoe.

C and D, approximately twice as long as A and B,

were used by the Ingalik and Kutchin Indians respectively, of the lower Yukon.

(W.H. Dall, The Yukon Territory [London: Downey, 1898], p. 190.)

5, The broader of the two Chilkat snowshoes was used for packing

supplies; the narrower, for hunting.

(Frederick Schwatka, Along Alaska's Great

River [New York: Cassell & Company (1885)], p. 87.)

|

The distinction between a transportation system and the modes of

transportation is important. A comparison of the forms of

transportation used by both the Indians and the whites in the Yukon, at least

until the introduction of steamboats on the Yukon River, reveals that

both were similar. Like the whites, the Indians were dependent on the

river during the summer months. With bark canoes, which provided the

principal means of travel, the Indians enjoyed sufficient mobility to

sustain their existence. Built by the women of each tribe, who stretched

the bark over wooden frames and pitched the joints to make them

waterproof, these canoes were propelled by either paddles or a

pole.2 In winter transportation was by dog sled, toboggan or

snowshoe. The sleds and toboggans were made of birch, the various

components being lashed together with leather thongs. No nails or wooden

pegs were used. The sleds were fitted with thin, broad runners designed

to bend with the declivities of the snow. The runners, in turn, were

shod with a thin veneer of bone and iced to reduce surface friction. The

Indian sleds were light and fast and capable of carrying heavy loads

over smooth ice. To assist the dogs pulling the sleds, the Indians

generally preceded them and broke trail with their

snowshoes.3

The climate established a seasonal pattern of transportation in the

Yukon characterized by the alternating use of water and overland forms

of travel that was to persist until the early 1950s. The effects of

this dependence on the climate and the rhythm to existence which it

produced were to have a marked influence on the history of the area.

III

The first whites to enter Alaska were the Russians. Though they never

pushed far enough into the interior to cross the boundary that separated

the Yukon from Alaska,4 they did establish a gateway to the

Yukon which was to be of vital importance throughout the 19th century.

That gateway was the Yukon River, via the port of Saint Michael, 70

miles north of the mouth of the Yukon. The Russians came in search of

furs and in the process established a commercial empire in Alaska with a

feudal society.5 The Russian monopoly went unchallenged until

the late 1830s and the 1840s when the Hudson's Bay Company, pursuing a

policy of westward expansion after their union with the North West

Company in 1821 and making use of a series of posts on the Mackenzie

River, broke through the barriers which had theretofore isolated the Yukon

from British commerce.

The fur trade, the magnet which drew the white men into the

Northwest, hinged on two factors: the existence of fur-bearing animals

and a network of water routes for transportation. The dependence of the

fur trade on the water routes was critical since these routes made the

Hudson Bay Company's penetration possible and prospective trading-post

sites were chosen "largely on the requirements of water transportation."6

Dependence on water travel survived long after the Company had withdrawn

from the Yukon; in fact, it characterized transportation in the Yukon

until the 1950s when the last sternwheeler on the Yukon River was

finally beached.

The Hudson's Bay Company broke through the natural barriers that

separated the Yukon from the Mackenzie District in a pincer movement,

using the Mackenzie River as the source for all exploration west. In

1840 Robert Campbell was commissioned by the Company "to explore the

north branch of the Liard to its source and to cross the height-of-land

in search of any river flowing to the westward."7 In May of

the same year, Campbell and a party of seven set out from Fort Halkett

on the Liard and followed that river to its junction with the Dease.

From there Campbell swung north to Frances River and on to a mountain

lake, which he named Frances in honour of Lady Simpson. Beyond the lake

he entered the Finlayson River, reached Finlayson Lake and portaged to

another river which he called the Pelly, after the governor of the

Hudson's Bay Company. He then retraced his movements and rejoined the

main party at Finlayson Lake.8 Two years later, in 1842, Campbell

established the first Hudson's Bay Company post in the Yukon at Frances

Lake.9 During the next six years Campbell opened up the

southeastern section of the Yukon for the Company, establishing another

site at Pelly Banks, and explored the Pelly, Lewes and Yukon rivers. In

1848 he built Fort Selkirk at the confluence of the Yukon and the

Pelly.10

In the meantime, traders of the Company had been active in extending

the trade to the northern portion of the Yukon using the Porcupine

River. John Bell, a chief trader, who had built Fort McPherson in the

North West Territory in 1840, discovered the Rat River and explored the

Porcupine to its mouth in 1842. In 1847 Alexander Murray was

commissioned to establish a post at the confluence of the Porcupine and

the Yukon. Leaving Fort McPherson in July of 1847, he proceeded to La

Pierre's House where he embarked in the Pioneer to the mouth of the

Porcupine. At the mouth of the latter river he selected a site for a

trading post and build Fort Yukon.11 Though located in

Russian America (later Alaska) just a few miles to the west of British

territory, the commercial advantage of locating at the junction of the Porcupine and

the Yukon outweighed diplomatic considerations in this remote area and

Fort Yukon become the focal point for the Company's dealings in the

northern Yukon.

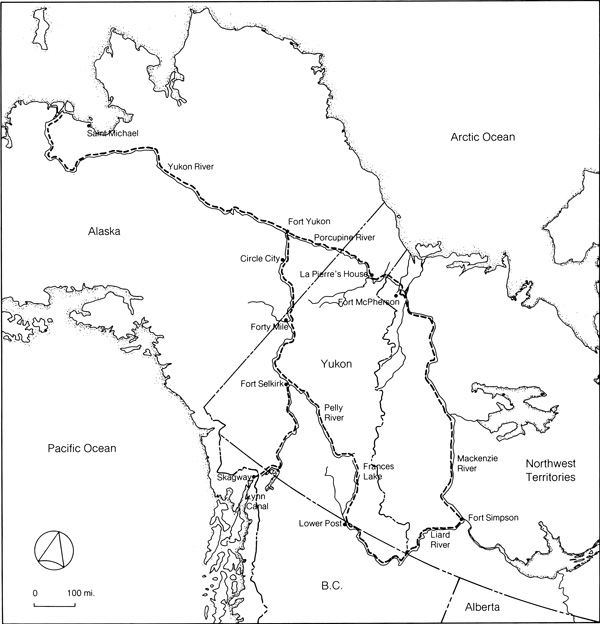

6 Routes to the interior.

(Map by S. Epps.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

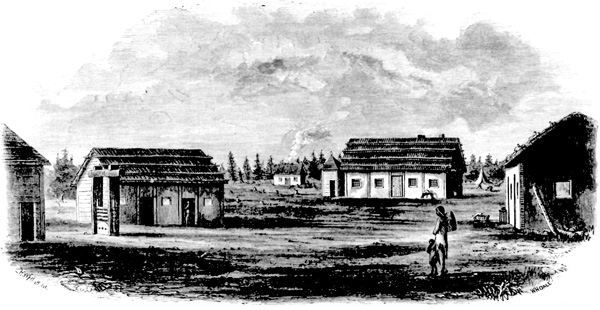

7 Fort Yukon, June 1867. The fort stockade, not shown, was later

used as fuel for steamers on the Yukon.

(W. H. Dall, The Yukon Territory [London:

Downey, 1898], facing p. 103.)

|

By 1847 the Hudson's Bay Company had established two water routes to

the Yukon from the Mackenzie River. In 1851 Robert Campbell made his

historic trip from Fort Selkirk down the Yukon River to Fort Yukon,

thereby establishing that the Yukon and the Pelly were on the same

watercourse.12 This discovery was of great significance.

Posts in the southern Yukon had always been difficult to provision

owing to dangerous travelling conditions on the Liard. With the

discovery that the Pelly and the Yukon were on the same watercourse, the

Liard route was abandoned in favour of the Porcupine.13 From

1852 until 1869, when the Hudson's Bay Company was expelled from Fort

Yukon by the United States government, the Porcupine was the main

gateway to the Yukon interior.14

The pursuit of the fur trade in the Yukon by the Hudson's Bay Company

was at best a marginal enterprise. The limitations of the transportation

system and the resulting high costs were factors that the Company was

never able to overcome. These difficulties were exacerbated by the

Indians' hostility to white incursion, a prime example of which was the

destruction of Fort Selkirk by the Chilkats in 1852. However, occasional

manifestations of open hostility by the Indians was secondary and in the

case of Fort Selkirk, possibly a consequence of the inadequacy of a

transportation system that made it difficult to supply the fort and

which only served to entice the Chilkats to take strong measures to

regain their historic monopoly over the trade of the southern interior.

Within the Company itself there had been a continuing debate over the

profitability of the Yukon trade. In arguing for the abandonment of the

southern posts, one chief factor noted that losses were incurred from

1848 to 1850 at the Frances Lake, Pelly Banks and Fort Selkirk posts and

that during its last year of operation (1851) Fort Selkirk showed a loss

again.15

An examination of the transportation problems that plagued the

Hudson's Bay Company illustrates the impossibility of conducting the

Yukon fur trade on a profitable basis from the East. According to Innis,

sleds employed by the Company in the Yukon were smaller than those used

elsewhere with the result that furs had to be packed in smaller

bundles.16 The isolation of the Yukon posts made provisioning

difficult and response to changing Indian trade demands almost

impossible. George M. Dawson, chief dominion geologist, later noted that

it had taken seven years for the returns from Forts Yukon and Selkirk to

reach the market. The course of trade was as follows:

Goods. — 1st year, reach York Factory; 2nd year,

Norway House; 3rd year, Peel River, and were hauled during the

winter across the mountains to La Pierre's House; 4th year, reach Fort

Yukon. Returns. — 5th year, reach La Pierre's House and are

hauled across to Peel River; 6th year, reach depot at Fort Simpson; 7th

year, reach market.17

As a result, the Company was forced to restrict the Yukon trade

to furs of high value, a fact which adversely affected its competitive

position with the Russians.18

With the expulsion of the Hudson's Bay Company from Fort Yukon in

1869, a phase of transportation history in the Yukon closed. During this

phase two river routes had been opened up to the Yukon interior. Neither

was to be of lasting significance. The very nature of the fur trade as

practised by the Hudson's Bay Company discouraged settlement and with it

the introduction of more highly developed transportation

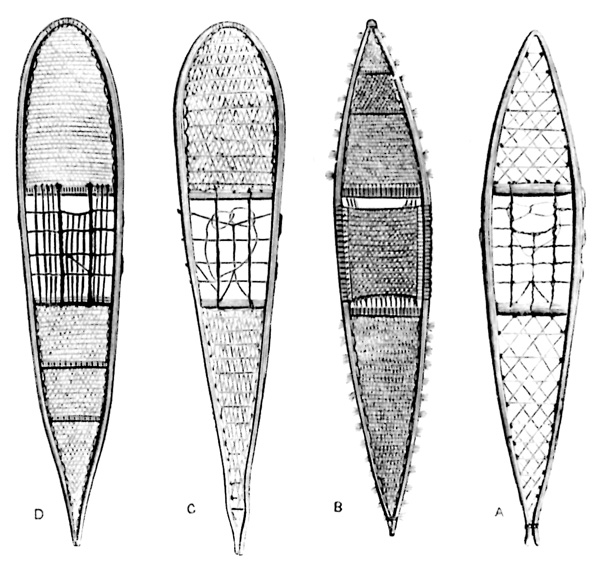

forms.19 The Company had employed the same conveyances as the

natives, with minor modifications. Of these the "Hudson Bay Sled" and

snowshoe were the most important. The former was, in fact, a toboggan

nine feet long made from three birch planks held together by

crosspieces. The load was carried in a large moose-skin bag lashed to

the sled. The toboggan style was adopted because it was more suitable

for carrying heavy loads than the conventional sled. Nevertheless, this

adaptation in favour of carrying capacity necessitated the sacrifice of

several useful features common to the more conventional style of sled.

As a result, the Hudson Bay sled was hard to guide, difficult to take up

a hill and practically impossible to keep on the trail when travelling

along a hillside. Because the floor of the sled rode close to the

surface, the load was subject to water and snow damage. Progress was

slow unless travelling over hard-packed snow. With this in mind, the

Company designed a special snowshoe for trail use. This snowshoe had a

packing effect which facilitated the movement of the sled. The Hudson

Bay snowshoe was small, 30 inches being the regulation length. It was

pointed at both ends, the front being curved upward and fitted with a

knob to break the crust. For other types of winter activity such as

hunting, the traders used a larger snowshoe modelled after the "Kutchin"

Indian style.20 Only at Fort Yukon, where two boats, 30 feet

8 inches long with 9-foot beams, were built in 1848, was any attempt

made to introduce boats and these were limited to the movement of goods

on the Porcupine River to La Pierre's House.21

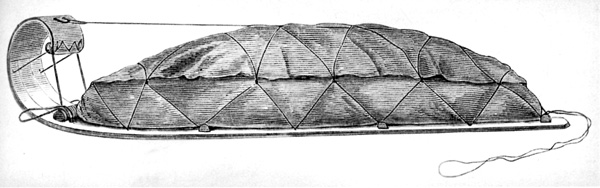

8, 9 Two versions of a Hudson's Bay Company sled. Figure 8 appears

to be a more accurate rendering of the sled.

(W. H. Dall, The Yukon Territory [London:

Downey, 1898], p. 165; Frederick Whymper, Travel and Adventure in the

Territory of Alaska [London: John Murray, 1868], p. 230.)

|

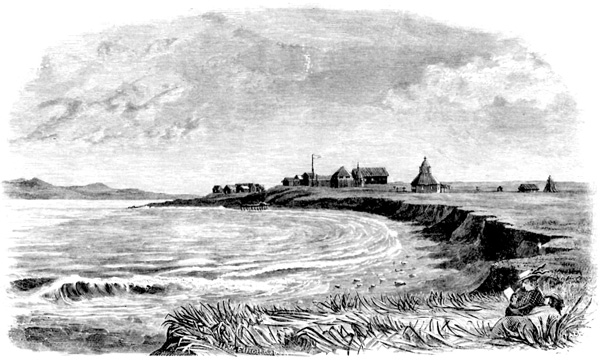

10 Saint Michael, Alaska, circa 1865. Located 70 miles from the

mouth of the Yukon, Saint Michael afforded the closest harbour

for ocean-going ships. Supplies were then transferred to river

boats and conveyed up the Yukon River.

(W. H. Dall, The Yukon Territory [London:

Downey, 1898], facing p. 11.)

|

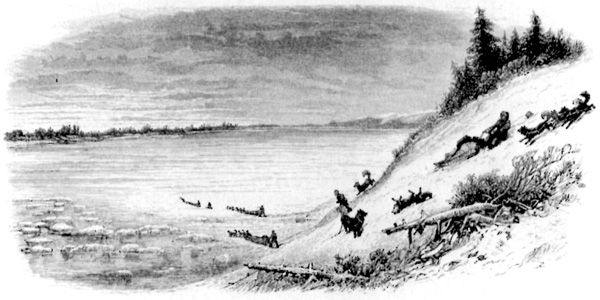

11 The mouth of the Yukon River, gateway to Alaska and the Yukon.

(Frederick Whymper, Travel and Adventure in the Territory of

Alaska [London: John Murray, 1868], facing p. 164.)

|

IV

In 1867 the United States purchased Alaska from Russia. While most

Americans tended to regard Alaska in much the same way as Voltaire had

regarded New France,22 one enterprising group of traders

turned its attention to the new American possession. The San Francisco

firm of Hutchinson, Kohl and Company, drawn to the Northwest by the

Pribiloff seal fishery, acquired the Russian trading posts and boats in

the territory. In 1868 the firm filed articles of incorporation

creating the Alaska Commercial Company.23 With the virtual

withdrawal of the Hudson's Bay Company from the Yukon in 1869, the

Alaska Commercial Company extended its interests to include the fur

trade of the interior and quickly established a commercial monopoly

over a region which included not only Alaska, but also the Yukon itself.

Until 1894 when Inspector Charles Constantine of the North-West Mounted

Police was despatched to the Fortymile district, the history of the

Yukon and Alaska can be said to have been virtually identical.

This period of Yukon history was characterized by two forms of

economic activity — fur trading and prospecting. With each passing

year, however, prospecting become the more important of the two. The

Alaska Commercial Company retained its interest in the fur trade, but

the trapping was done by Indians or prospectors who sought to supplement

the small returns from their diggings. Unlike the Hudson's Bay Company

experience, the two forms of economic activity proved to be relatively

complementary under the aegis of the Alaska Commercial Company.

The establishment of the Alaska Commercial Company in Alaska and the

Yukon led to the abandonment of the old Hudson's Bay Company trade

routes. After 1867 the principal gateway to the Yukon interior was the

Yukon River via Saint Michael. The adoption of the old Russian trade

route after 1867 had a profound effect on the development of

transportation in the Yukon. It not only involved a significant change

in access, but also made possible the introduction of steam-powered

vessels — the first major technological innovation in the

transportation history of the Yukon.24

The first steamboat on the Yukon River was the Wilder, a small

craft employed by the Russian-American Telegraph Company.25

W.H. Dall, an American explorer, likened the vessel to an old-fashioned

flatiron and remarked that it was "just about as valuable for the

purpose required. Unable to tow anything, or to carry any freight, while

in a breeze of any strength it was no easy matter to steer," the

Wilder can hardly be said to have marked an auspicious debut for

a form of transport that was to dominate Yukon transportation for

almost a century.26

Regular river service was introduced in 1869 when the Alaska

Commercial Company launched the sternwheeler Yukon and augmented

two years later with the launching of the Western Fur and Trading

Company's St. Michael. Both were small craft, 70 to 80 feet in

length, 14 to 20 feet in width, with a draft of 3 to 4 feet. Fitted with

powerful wood-burning engines, each boat was designed to push a barge

when necessary, each barge having a maximum capacity of ten tons. The

Canadian surveyor William Ogilvie, who had been commissioned to

establish the 141st meridian for boundary purposes and who was to later

enjoy a conspicuous place in the history of the gold rush, wrote that

the Yukon "could make a round trip from St. Michael to any point

in the vicinity of the boundary line in about a month, the upstream time

being twenty days." In 1871 the Yukon went up the river as far as

Fort Selkirk. Until 1898 when sternwheelers began to run on the upper,

or Bennett-Dawson, section of the Yukon River, no sternwheeler ever went

above the site of Campbell's old trading post.27

It was the fur trade that had lured the Alaska Commercial Company to

the Northwest. By the early 1870s, however, a new interest was

generated which was to overwhelm the trade in furs and almost totally

replace it.28 This new interest was gold.

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 precipitated a stampede

to the West Coast the following year. After the first burst of activity

in the California gold fields had passed and as individual mining

methods were steadily superseded by more advanced forms of mining

technology, the majority of those who had set out for the West Coast

settled down to the less romantic but profitable pursuit of settling

California. The rush to California had given birth to a breed of men,

however, to whom the search for gold was to become a lifelong obsession.

Beginning in the early 1850s, these men rushed to every new gold camp,

only to abandon it when news of another discovery reached them.

By the 1860s the trail of gold camps had led to the Cariboo district

in British Columbia.29 The expansion of gold-mining activity

in the West, beginning in California and culminating in the Cariboo,

had followed a roughly northern course. This pattern of expansion

suggested to some of the more speculative prospectors that there might

be a belt of gold running north to south on the western lip of the

hemisphere that had its source somewhere in the Yukon or Alaska. In the

early 1870s these men began to trickle into the Yukon to test their

hypothesis.

Of these men, four stand out as major figures in the history of the

Yukon: Leroy Napoleon "Jack" McQuesten, Al Mayo, Arthur Harper and

Joseph Ladue. McQuesten, Mayo and Harper reached the north in 1873 via

Fort Yukon and the Porcupine River. In 1874 they entered the employ of

the Alaska Commercial Company.30 During the next 20 years

they opened trading posts, prospected, and assisted other prospectors

throughout the territory with supplies, credit, transportation and

advice. Joseph Ladue joined them in 1882.

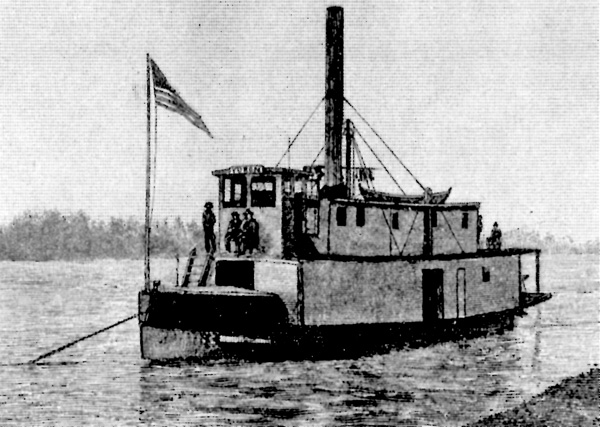

12 The Alaska Commercial Company steamer Yukon.

(U.S. Army. Department of the Columbia,

Report of a Military Reconnaissance in Alaska, Made in 1883, by

Frederick Schwatka [Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1885], p. 44.)

|

13 The SS St. Michael, grounded on a bar near Fort Yukon.

Owned originally by the short-lived Western Fur and Trading Company

(also referred to as the Northern Trading Company), the St.

Michael was subsequently taken over by the Alaska Commercial Company.

(U.S. Army. Department of the Columbia, Report of a Military

Reconnaissance in Alaska, Made in 1883, by Frederick Schwatka

[Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1885], p. 43.)

|

14 Juneau, Alaska. Before the Klondike gold rush, Juneau was the main

outfitting port for prospectors bound for the Yukon via the Chilkoot

Trail. It was the last port-of-call for vessels running up the Inside

Passage and the place where prospectors arranged for transportation

to Dyea.

(Chicago Record, Klondike [Chicago: Chicago

Record Co., 1897], p. 92.)

|

It might be said of each of these men that they were frustrated

miners. None of them ever discovered the gold that had drawn them north,

but they were not failures. Without them, as Pierre Berton has

appropriately written, "the series of events that led to the Klondike

discovery would not have been possible. Without the string of posts they

set up along the Yukon, the systematic exploration of the river country

could not have taken place."31 This string of posts, moreover,

furnished a framework for the first internal transportation network in

the Yukon.

Excepting the major innovation in navigation that took place in the

late 1860s, no significant change in the Yukon transportation system

occurred until the early 1880s when a new route to the Yukon was opened

up. Located at the head of Lynn Canal, this new gateway originated at

Dyea, led over the Chilkoot Pass to the mountain-fed lakes in

northwestern British Columbia and down the Yukon River. For years the

Chilkat Indians had guarded the pass, denying the white man access in

order to protect their trading monopoly with the Indians of the

interior.32 In 1878 a prospector by the name of George Holt

used the pass and is generally recognized to have been the first white

man to successfully deny the Indian interdict.33 Two years

later the pass was opened to all when the USS Jamestown used

gunboat diplomacy to "persuade" the chief of the Chilkat Indians to

allow free access to it. From 1881 the Chilkoot Pass became the main

portal used by miners going into the Yukon.34

Movement over the Chilkoot Pass was difficult, the trail being a

veritable obstacle course. The path over the summit, steep and

rock-strewn, made it impossible to use pack animals for the through

journey between Lynn Canal and the lakes on the other side.35

The Chilkat Indians, no longer able to restrain the whites from using

the pass, turned the situation to their own advantage by taking up the

profitable pursuit of packing prospectors' supplies over the

summit.36

With the discoveries of gold along the bars of the Stewart River in

1886 and on the Fortymile in 1887, the influx of miners into the region

increased in intensity. As a result, a pattern that had begun to emerge

as early as 1882, when prospectors first began to use the Chilkoot

Trail, was established by 1887. This pattern was to persist with only

slight modification up to and including the gold rush of 1898.

There has been an unfortunate tendency to associate everything

pertaining to the Klondike gold rush with having been a product of it.

Nowhere has this tendency been more misleading than in the history of

the development of transportation in the Yukon. A cursory examination

of what took place during the 1880s, with specific reference to the

Lynn Canal gateway to the interior, reveals that the main outlines of

the gold-rush transportation system had been laid long before

1897-98.

In 1886 a trading post was built on the tidal flats at Dyea by John

J. Healy. Here the prospectors debarked from steamers which had carried

them up the Inside, or Inland, Passage, purchased their supplies and

made arrangements with Healy for the packing of their possessions over

the trail. Thus the first organized economic enterprise to serve miners

going into the Yukon from the Alaska Panhandle predated the gold rush by

12 years. By 1887 Sheep Camp, three-quarters of the way up the Dyea

trail, had been established as the main stopping-off point on the

coastal side of the pass, just as it was to be during the gold

rush.37 As early as 1887, prospectors were whipsawing timber

and building boats at Bennett Lake for the trip down the Yukon River and

William Ogilvie's observation, made in the same year, that the supply of

lumber for boat building had become practically exhausted suggests that

this had been going on for some time.38 The tent city of

thousands that ringed the southern bank of Bennett Lake in the spring

of 1898 may have shocked the newspapermen who were despatched by their

publishers to report on the Klondike phenomenon, but to those who had

been in the Yukon for some years it was only the culmination —

surprising in its extent to be sure — of a process that had begun

at least ten years earlier.

In retrospect, the 1880s stand out as a decade of great progress in

laying the framework of the gold-rush transportation system. For the

first time accurate information was accumulated concerning

transportation routes as a result of the explorations of Frederick

Schwatka, an American army officer, and Canadians George M. Dawson and

William Ogilvie.39 A portage road, replete with rollways and

windlasses to transfer boats, was built in 1887 on the east bank of the

Yukon River across from the present townsite of Whitehorse to bypass the

Whitehorse Rapids.40 In the same year, Dawson notified the

minister of the Interior that Edward Bean had obtained permission from

the United States government to build a road over the White Pass, some

six miles east of the Chilkoot, and reported the rumour that a railroad

was to be built over the Chilkoot.41 Although Bean had

petitioned the secretary of the Interior for a franchise to construct a

trail over the White Pass, his request had been refused on the grounds

that Congress was the only body empowered to grant franchises. Bean was

not the last person to seriously contemplate a trail over the White Pass

before the gold rush. At least two more unsuccessful applications for a

franchise were made, one in 1888, the other by William Moore in

1891.42

15 Near Dyea, Alaska, the southern terminus of the Chilkoot Trail,

in the early 1880s.

(Frederick Schwatka, Along Alaska's Great

River [New York: Cassell & Company (1885)], p. 65.)

|

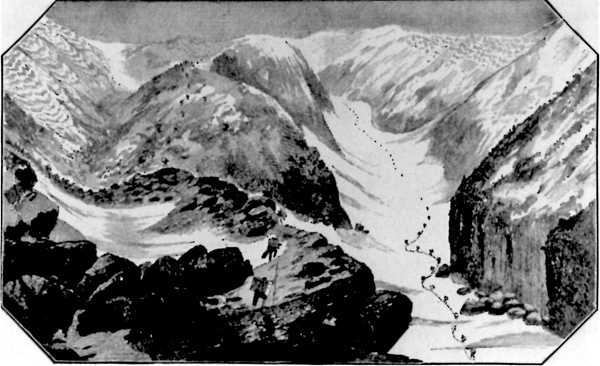

16 An artist's impression of the Chilkoot Pass (Schwatka's Perrier

Pass) 14 years before the great stampede. Schwatka named many of

the geographical features on the Chilkoot and upper Yukon.

(Frederick Schwatka, Along Alaska's Great

River [New York: Cassell & Company (1885)], p. 85.)

|

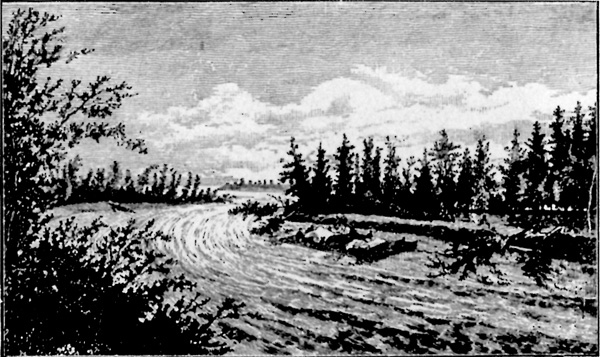

17, 18 Navigation problems on the upper Yukon River. 17,

A raft negotiating sweepers (trees or brush disloddged by

riverbank erosion). 18, Running aground was much more

common and often meant long hours of unloading, easing the craft

off the bar and reloading before once more getting under way.

(Frederick Schwatka, Along Alaska's Great

River [New York: Cassell & Company (1885)], p. 134, 145.)

|

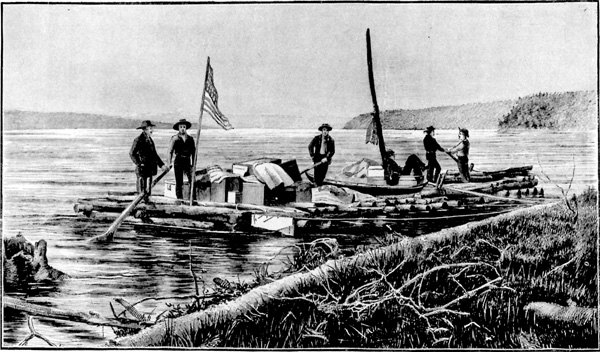

19 The raft which carried U.S. Army lieutenant Frederick

Schwatka and party from the headwaters of the Yukon to

central Alaska in 1883.

(Frederick Schwatka, Along Alaska's Great

River [New York: Cassell & Company (1885)], p. 311.)

|

While none of these schemes bore fruit, they do suggest that the

pre-gold-rush Yukon showed enough economic potential to justify

speculative consideration being given to substantial improvements to the

transportation system. Furthermore, they suggest that ambitious

transportation schemes were not simply products of gold-rush hysteria.

While it is important to bear in mind that charter and/or franchise

applications do not necessarily prove serious intent on the part of the

applicant, it should be noted that governments, not individuals, were

the usual risk takers in the construction of "development" roads during

the 19th century and that the absence of legislation providing for a

franchise — and to an even greater extent the corollary subsidy

— may well have been a factor in postponing a series of schemes

that was economically premature.43

To serve the ever-growing human influx, sternwheeler operations on

the lower river were expanded. In 1883 a small sternwheeler, the

New Racket, was constructed. The Alaska Commercial Company built

the Arctic, one of the first of the larger boats on the lower

river (140 feet long, 28 feet wide, with a 6-foot hull), in 1889 and it,

like its predecessors, made the Saint Michael-Fort Selkirk

run.44

In 1892 the monopoly of the Alaska Commercial Company was broken with

the formation of the North American Transportation and Trading Company,

a Chicago-based firm with its Yukon headquarters at Cudahy. An immediate

result was a reduction in prices and the supplying of better goods by

both companies.45 Another significant consequence was the

North American Transportation and Trading Company's decision to go into

the navigation business. The Portus B. Weare, the first of the

company's sternwheelers, was placed in service in 1892. A short time

later the John J. Healy followed. Responding to the challenge of

its new competitor and to the needs of the growing northern population,

the Alaska Commercial Company added the Alice (1895) and the

Bella (1896) to its fleet of river boats.46

Excepting the introduction of steam-powered vessels on the lower

river, modes of transportation remained primitive between 1869 and 1896,

just as they had been during the Hudson's Bay Company's presence.

Canoes, rafts and sleds continued to be the principal forms of domestic

travel, the birch-bark type of canoe giving way to cottonwood dugouts

after 1869.47 Poling boats were introduced by the miners

during the 1880s and used on the Yukon River and its tributaries. They

were particularly well-suited to upstream travel. Long, narrow, and

pointed at both ends, these craft were propelled by two men sinking

poles through the water and pushing on the riverbed. At times the poles

were augmented by a canvas sail.48

An important innovation in overland travel occurred during this

period with the introduction of horses.49 The earliest record

of horses in the Yukon dates from 1891 when Jack Dalton and E.G. Glave

brought horses in over what was later to be known as the Dalton

Trail.50 There is also evidence to suggest that horses were

used infrequently at Dyea before this time, but the nature of the

Chilkoot Trail prevented them from being brought into the Yukon

profitably. Another factor limiting the use of horses was the lack of

food. It was generally believed that native grass was not nutritious

enough to sustain horses and the costs involved in bringing in hay were

too high to make importation feasible. There was also some discussion as

to whether horses could withstand the climate and, since it was felt

that horses would have to be shod, it was believed that the iron shoes

would freeze solid to the ice or else freeze the horses' feet. Despite

these apparent drawbacks, horses were brought into Forty Mile in 1893

and were in general use at Circle City after 1894.51 However,

the horse did not seriously challenge the status of the dog as the

primary motive force in overland transportation during this period.

V

On the eve of the Klondike gold rush the Yukon interior was served by

two transportation networks, each originating in Alaska: one on Lynn

Canal, the other at Saint Michael. Each fulfilled a separate function.

The former was the avenue of migration, the latter the highway of trade.

In keeping with this functional nature, the forms of transportation for

each were distinct. The lower river was the private preserve of the

sternwheeler and the trading companies.52 The Lynn Canal, on

the other hand, was atomistic in nature, serving individuals or small

parties of prospectors who crossed the Chilkoot Pass on foot and

travelled down the Yukon River system in small boats of their own

construction. Interestingly enough, both of these networks were to

retain their pre-gold-rush characters during the great stampede.

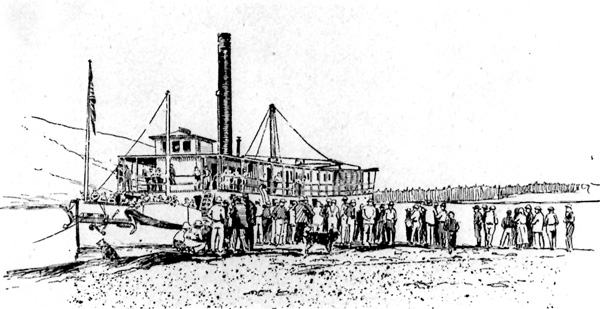

20 The arrival of a steamboat was an occasion. Whole settlements

would greet the latest purveyor of goods and news from the

outside.

(Chicago Record, Klondike [Chicago: Chicago Record

Co., 1897], p. 268.)

|

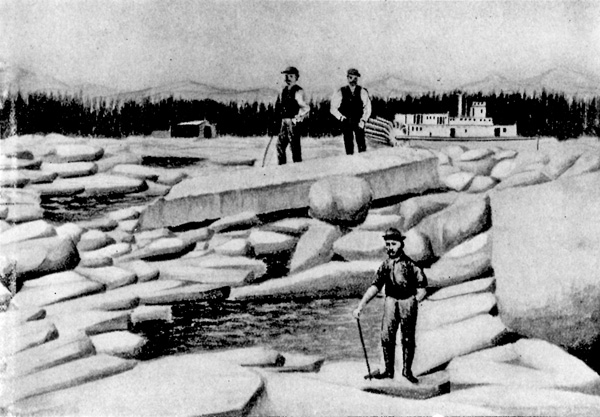

21 Seasonality was the one obstacle river transport never

surmounted. Here the Portus B. Weare is trapped in

the ice at Circle City while its crew looks in vain for a

channel.

(Ernest Ingersoll, Gold Fields and the Klondike

and the Wonders of Alaska [n.p.: Edgewood (1897)], p. 338.)

|

|