|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 19

Yukon Transportation: A History

by Gordon Bennett

Between the Wars

I

"A gold rush is like a war," George Black once explained. "You feel

it in your blood. It is exciting — intoxicating. It reveals, as in

a flash, the monotony of ordered days and ordered ways."1 By

1914 the prospect of another Yukon gold rush was little more than an

empty dream. Most of the Klondike had come under the umbrella of

consolidation and what remained would have been hard put to bestir the

enthusiasm of the most optimistic prospector. The "intoxicating" days of

1897-1900 were gone forever, replaced by the daily routine of working

for one of the large mining companies.

If another gold rush was merely the product of an imaginative mind

nourished by the interminable Yukon winter, war was not. When

hostilities broke out in Europe in August of 1914 a certain exhilaration

swept the Yukon. Black's description of the stampede spirit worked both

ways and war, though certainly less preferable than a gold rush,

nevertheless furnished excitement and relief from the "monotony of

ordered days and ordered ways" that had become the measure of life in

the territory.

But the excitement was purchased at tremendous cost. While the rest

of the nation shared, albeit with some disparity, the benefits accruing

from wartime mobilization,2 these benefits, with the notable

exception of the Whitehorse copper industry, completely by-passed the

Yukon. The impact of the war on gold mining — the backbone of the

territorial economy — was particularly severe. From 1908 through

1914 the industry had exhibited positive signs of recovery after seven

years of decreasing annual production.3 Under the influence

of wartime conditions, however, the industry found itself caught in a

vice of rising production costs and rigid gold prices. Writing in 1918,

the territorial gold commissioner observed that "each successive year

since 1914 has seen a tremendous increase in the price of all kinds of

provisions and particularly in dredge machinery and repair parts, and

there has been no increase in the value of gold mined."4 The

price-cost squeeze was further exacerbated by the withdrawal for war

service of a large number of skilled miners and supervisory personnel, a

factor that adversely affected the operational efficiency of the

industry.5 Given the region's remoteness and the inflationary

pressures unloosed by the war, it was impossible to replenish such a

drain on the labour pool from outside sources.

Within the territory itself, the war produced spectacular increases

in the cost of living. Operating on the barest of margins, the gold

companies were forced to deny labour a corresponding measure of wage

relief. In 1917 the Yukon Gold Company, the only mining concern in the

Klondike extracting enough gold to qualify as a genuine producer,

rejected the moderate demands of its employees for a "10 per cent

increase [in] wages to meet [the] 60 and 100 per cent rise on

foodstuffs." The company's intransigence was followed by an act of last

resort in an industry wholly dependent on seasonal operation: a

strike.6

No less serious than the war and of greater long-term consequence

were the managerial decisions taken within the gold mining industry

itself. During the period 1908-35 extractive operations were undertaken

on less than half the known gold-bearing fields in the Klondike. This

failure to exploit to the full the resources of the district cannot be

attributed to a deliberate policy of building up reserves and following

a programme of systematic extraction, a policy that would have been

economically sound. Rather it must be explained in terms of a single

individual's attempt to gain hegemony over the entire gold fields, an

attempt that was characterized by an almost total disregard for the

welfare of the Yukon.

It is ironical that this individual, A.N.C. Treadgold, was the

architect of consolidation. For it was Treadgold, with his intimate

knowledge of frozen gravels and the most efficient means for working

them, who had been largely responsible for the conversion to

capital-intensive mining. But Treadgold was obsessed by an even greater

dream than overseeing the revolution in mining technique which he had

initiated; he dreamed of bringing the entire Klondike under his personal

control.

Treadgold pursued his goal through the simple expedient of using the

assets of the companies with which he was associated to purchase

additional claims. Had he financed these purchases out of the profits

realized from his mining operations, he might well have achieved his aim

and maintained at the same time a satisfactory level of production, but

Treadgold employed investment capital which should have been used to

underwrite extraction. Francis Cunynghame, Treadgold's biographer, has

written that under Treadgold's stewardship, the Granville Mining Company

was "a mining company which could not produce gold and had no means to do

so."7 The same can be said of all the companies with which

Treadgold was later connected. Percy Reid, territorial gold commissioner

during the mid-1920s, expressed his exasperation with Treadgold by

dismissing him as little more than a speculator: "Mr. Treadgold is not

an operator, but is merely a promoter."8 As unfair to

Treadgold as Reid's assessment was, the gold commissioner accurately

captured Treadgold's fatal weakness that was to deprive the mining

industry of the liquid capital required to maintain its productive

capacity. The outcome of Treadgold's dream to control the Klondike was

to leave gold mining proper in a relative state of suspended animation

between 1918 and 1932 and bring about his ultimate

downfall.9

The impact of the war and Treadgold's struggle can be seen in the

annual figures for gold production published by the Dominion Bureau of

Statistics. Between 1915 and 1930 there was a protracted falling off in

production from a high of $5,125,324 in 1914 to $734,202 in 1930.

Between 1924 and 1932 total annual production did not exceed one million

dollars, hitting a low of $529,220 in 1926. In 1923 silver-lead

production in the Mayo district superseded the Klondike as the principal

mineral-producing region in the Yukon.10

On a more tangible plane, the decline in gold production found a

mirror image in the community of Dawson. Where once the mud flat at the

confluence of the Klondike and Yukon rivers had played host to an

estimated thirty thousand people, 975 were all that could be mustered

for the 1921 census.11 While falling production and a

decreasing population were not novel phenomena, Dawsonites reacted to

them in a manner that was far different after 1918 than had been the

case prior to the war. Before the war there had been a pronounced

tendency to regard post-gold-rush Dawson as a settled, progressive

community that had evolved out of the raw mining camp synonymous with

the stampede. But the war, the economic havoc created by Treadgold's

ambition to control the Klondike, and the sinking of the SS Princess

Sophia in October of 1918 destroyed this complacent

perspective.12 When Laura Berton returned to Dawson in 1920,

Dawson was not the confident little enclave she had left four years

before, but a "decaying town" sapped of its energy and spirit. The

unmistakable signs of a ghost town in the making were manifest.

Physically, the settlement possessed enough buildings to accommodate ten

times its population. The population itself, already ravaged by war, a

waning economy and the Sophia disaster, was getting progressively

older. A generation separated the Dawson of 1897-1900 from the Dawson of

1920. In the interim, immigration had been negligible. Dawson's single

hospital was full "not of patients," Mrs. Berton wrote, "but of old

men." Funerals became social events. Where a quarter of a century

before, Dawson had revolved around the gambling tables and the dance

halls, "it was the funerals around which the town revolved" during the

twenties.13

By 1920 the Dawson Daily News, the only local newspaper to

survive the century's first decade, had ceased daily publication. Four

years before, the News had carried an obituary to an era of

social history with a banner headline that proclaimed "Last Day of the

Saloon in Yukon." In 1918 the Side Streams Navigation Company of Dawson

terminated its operations, while in the same year the United States

government withdrew its consular representative from the city. At the

end of the war the total annual tonnage arriving at Dawson had declined

to less than ten thousand tons and in the words of G.B. Edwards, general

agent for the British Yukon Navigation Company, "waterfront privileges

are fast depreciating." By 1920 the only living reminder of Dawson's

golden age as an entertainment centre was a single theatre, but one

would have been hard pressed to find any resemblance between the

productions and the performers of 1899 and 1920.14

If one word best described the Dawson of 1920, that word was

"shrinkage." One could see it everywhere — in the population

figures, in the economy and in the spirit of those who remained. Even

the city itself was shrinking. Community services were too expensive to

provide over a widely scattered area and as a consequence there was a

steady concentration of people toward the core. But Dawson had a history

of escaping the ghost town fate so often predicted for it after 1900. In

this there was an unfailing and perhaps to some a perplexing

consistency. The twenties were difficult years for Dawson, but the town

survived them and when the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation commenced

full-scale production after 1933, Dawson was ready once more to preside

as the Yukon's major city.15

The Klondike's postwar economic slide was in large measure offset by

developments that occurred in the Mayo district during the late teens

and early twenties. The discovery of a rich silver-lead outcropping by

Louis Bouvette on Keno Hill in 191916 climaxed a 13-year search for an

extensive lode deposit in the area17 and attracted two large

companies, Keno Hill, a subsidiary of the Yukon Gold Company, and the

Treadwell Yukon Company of San Francisco, with sufficient capital to

organize the industry on an efficient basis. With the withdrawal of Keno

Hill in 1924, the way was cleared for Treadwell Yukon to establish

virtual control over the entire district. This it did with the result

that by 1926 the Mayo district and silver-lead surpassed the Klondike

district and gold as the primary producer and product in the

Yukon.18

This radical change in the territory's economic centre of gravity had

a profound impact on the transportation system. At the very time that it

was becoming increasingly apparent that the territorial economy could no

longer sustain the existing transportation system, a new challenge

issued from the Mayo district.19 This challenge was

substantially different from the challenge that had been posed in the

Klondike. It demanded a response to the transportation problem that was

in keeping with the peculiar needs of lode mining as distinct from

placer mining. In the past the transportation system had proved

singularly incapable of coming to grips with a problem of this

nature,20 but the mineral deposits of the Mayo district

enjoyed two palpable advantages over those of other areas where lode

mining had previously been attempted; a rich assay and extensive

occurrence. As a consequence, transportation was able to fulfill its

proper function; to assist a viable mining industry in moving the

products of the mine to outside buyers and to deliver the manpower and

material needs of the industry to the site of its operations. This

constituted a major shift in the burden previously borne by

transportation vis-à-vis the lode-mining industry. In the case of

Whitehorse copper, for example, transportation had been charged with the

impossible task of sustaining an industry that was initially tenuous

owing to the low-grade nature of its product.

II

That aspect of transportation most sensitive to the economic changes

of the 1920s was the road system. As we have seen, overland

transportation of the non-rail variety had assumed an ever-increasing

importance in the years immediately preceding the war, both as a

necessary adjunct to the seasonal service furnished by water and as a

vital tool in the movement of supplies and services between settlements

which were not situated on existing river routes. This was particularly

true of the Mayo district where mining properties tended to be scattered

over an area that was 40 miles from the nearest steamboat landing, the

town of Mayo, and the most accessible waterway, the Stewart River. Given

the resource base of the Mayo economy, transportation of a cheap and

efficient variety was crucial. As J.S. McNeill, the territorial

superintendent of roads explained, success in lode mining

depends in great measure on low freight rates, the grade of ore

which can be profitably mined depending largely on this item. Supplies

and equipment are needed in large quantities, and the product mined for

shipment is of a nature that involves considerable

tonnage.21

Unfortunately, events were taking place in Ottawa that would undercut

the realization of an efficient road system. Prodded on by the

opposition which claimed that the federal grant in support of the Yukon

was excessive, the government began a hard examination of its annual

Yukon appropriation. In one exchange recorded by Hansard in 1917,

an opposition MP stated that "little short of $1,000,000 was being paid

by Canada for the 9,000 people or thereabouts in the Yukon." "This is a

huge figure," he argued.

In going through the various items last year, I did not find the

slightest regard was paid to the changed conditions [declining

production and population].... It simply amounted to this, that it cost

about $100 per head to keep those 9,000 people in the Yukon. When the

proposition is put that way it does not look very

economical.22

In psychological and economic terms, the introduction of federal

retrenchment measures after the war could not have occurred at a more

inopportune time. The territorial economy was at a critical juncture.

The silver-lead industry had yet to progress beyond the developmental

stage and a sizeable investment was required to encourage further

development. Geographic decentralization of the resource base, the

bugbear of any remote region dependent on primary industry, made

difficult, if not impossible, the implementation of policies designed to

operate on the "economies of scale" principle and created conditions

whereby a costly duplication of services could not be avoided.

Paradoxically, reductions in government spending coincided with an

upswing in the economic outlook of the territory. In the Yukon there was

a general feeling that for the first time in 20 years the future was

bright. Departmental estimates for the 1921 fiscal year, however,

offered clear proof that the government did not share this confident

appraisal of the territory's future. Expenditures were cut by 35 per

cent over the previous year, an action that was regarded in the Yukon as

evidence that the government was "very ignorant of or absolutely

indifferent to the real situation here." Compared with the appropriation

expended in 1914, the estimates for 1921 represented a reduction in

government spending of 64 per cent.23

Territorial reaction to the course adopted by Ottawa was bitter. In a

hastily despatched night letter to the then prime minister, Arthur

Meighen, the Yukon Development League "respectfully" reminded him that

the

Yukon gave more men and money per capita to the Dominion for war

purposes than any other section of Canada without receiving [a] cent

[of] war business. Our only industry [gold mining] was severely

handicapped during [the] war... but we carried on and produced gold for

the Dominion... and why the government should now try to put Yukon

almost entirely off the map of Canada, the loyal and patriotic subjects

here cannot understand.

The league asserted that few facets of territorial life would escape

the adverse effects of the government's fiscal policies. Schools,

hospitals and libraries would be forced to close for want of support

while assistance for the indigent would have to be eliminated. That

facet most seriously affected from the viewpoint of the territorial

authorities, however, was the overland transportation system, for

federal retrenchment was effected in large measure at the expense of

road construction.24

Despite the territory's indignation and the growing evidence of the

importance of the Mayo strike, the dominion government refused to modify

its position. Considering the thrust of federal economic policies during

the 1920s, this is hardly surprising. While the minister of the Interior

conceded that there existed "a persistent demand for road construction

to enable people engaged in mining to get out the products of the mine,"

very little in the way of an increased appropriation was

forthcoming.25

An alternative source of money to finance construction was derived

from government-run liquor store revenues.26 Another was the

Mayo mining companies, especially Treadwell Yukon. This last was

particularly significant as it gave Treadwell Yukon an important voice

in determining the location and nature of roads in which it had an

interest. It also brought to an end an era in which the government had

assumed exclusive responsibility for building and maintaining Yukon

roads.27

During the 1920s the policy of the territorial administration was "to

maintain the main or trunk roads in as good a condition as finances

[would] permit; and, where possible, to assist in constructing trails

from these main roads to districts which show reasonable promise of

development." In determining the location for a road in the Mayo

district, the superintendent of Public Works, J.S. McNeill, would

appraise the wishes of the transportation company serving the route.

While this type of consultation was generally fruitful, it was not

always successful. As McNeill candidly admitted, most of the teamsters

"had their own ideas on what would be the best route" and in one case a

road was built which did not prove satisfactory to the ore-hauling

contractor and alterations were necessary. In the Klondike, where a

different set of economic conditions prevailed, road requirements

remained relatively static throughout the 1920s, There, government

policy was primarily confined to maintaining existing roads rather than

undertaking new construction. Before the commencement of each new mining

season, the territorial public works department would canvass the mining

community for a list of creeks on which operations were planned for the

coming year in order to avoid maintaining those roads which would not be

used.28

Two aspects of road building that had not seriously interfered with

road construction in the Klondike, permafrost and the time lapse between

starting and completing a road, proved to be serious impediments to

traffic movement in the Mayo district. While roads had been built in

sections and brought up to standard over a period of years in the area

tributary to Dawson, increased road use in the Mayo district, both in

terms of frequency and tonnage, required more rapid completion and a

higher standard of construction. In 1922 the Mayo Board of Trade

telegraphed the minister of the Interior to "strongly urge" the passage

of a sufficient appropriation to complete the trunk road between Mayo

and the town of Keno, the centre of the silver-lead mining industry,

"this season instead of spreading it over [a] number of years." The

government's response was that "a reasonable amount of money" should be

put aside for roads in the Mayo district. Lack of funds was one of the

chief obstacles to road building. As McNeill observed, "It cannot be

expected that we can make a good road from one year's appropriations,

but whatever amount of work that is done will represent progress along

permanent lines."29

95 Mud.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

96 Road construction at Sulphur Creek, 1937.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

In the early years road builders had circumvented the problem of

permafrost by not disturbing permanently frozen ground and by ensuring

that enough insulation covered the ground to prevent melting. This was

an adequate solution so long as roads were essentially temporary and

not subject to heavy use. Such was not the case in the Mayo district,

however, and as a result, an improved technique for dealing with

permafrost was developed. The ground was allowed to thaw, the thawed

portion being then removed. Approximately three years were required to

establish the desired depth and width of the road. The same procedure

was followed in roadbed preparation, the object being a stable

foundation for the road surface. Temporary changes in soil consistency

during the thawing period made drainage a constant problem throughout

the construction phase and required much ditching.30

The introduction of motorized vehicles in the early twenties was

another factor tending toward improved roads. After 1912 an extensive

network of roads had been built by the territorial government to connect

the placer camps in the then Duncan district with the head of navigation

at Mayo.31 These roads were designed "to a standard that

would allow of wagons being used during dry weather with moderate

loads."32 While adequate to the demands of placer mining,

these roads were not able to satisfy the transportation needs of the

silver-lead industry. In 1915 the cost of freighting one ton of ore

overland from the mines to the town of Mayo was $20, compared to a

figure of $22 for transhipment from Mayo to San Francisco. Overland

shipments, moreover, were limited to the winter period exclusively in

order to take advantage of the superior road surface furnished by

snow.33 That this shipment and others like it returned a

profit in spite of the high cost of transportation was due to two

factors — the existence of extremely rich ore and the method of

hand sorting. Selected ore samples from Galena Creek taken during the

1915 season, for example, were assayed at $153.00 to $266.72 a ton and

while ore of comparable value occurred only irregularly, many deposits

showed commercial promise.34 Hand sorting, or "hand-cobbing"

as it was also called, was a simple variation of the high-grading

technique used by gold miners during the rush and entailed manual

separation of high-quality ore from that of low value for shipment to

the smelter. Nevertheless, establishing the industry on a firm

foundation demanded more than simply relying on rich ore occurrences and

the costly, time-consuming method of hand sorting. What was needed was a

breakthrough in the transportation impasse between the towns of Keno and

Mayo Landing.

It is not surprising that the first attempt to resolve this difficulty

involved a railroad. In January 1921 a company was organized to build a

railway from the junction of the Mayo and Stewart rivers to the

McQuesten, by way of Mayo River, Duncan Creek and Crystal Valley. This

scheme wrought a counter proposal from interests representing the

defunct Klondike Mines Railway to extend their line from Dawson to the

silver camp or, alternatively, to construct a railway from Mayo Landing

to the mines. Although a federal charter was secured by the former in

March of 1921, construction was never begun and, despite its intimations

to the contrary, the Klondike Mines Railway Company showed no further

inclination to take on the project.35

In light of the failure to construct a railroad and in the absence of

sufficient government assistance for road building, the Mayo district

operators were forced to confront the transportation problem on their

own. In 1922 Treadwell Yukon pressed a ten-ton Holt tractor into

service. The experiment was a marvellous success, the tractor moving

forty-five hundred tons of ore that season from the mine to Mayo

Landing. The introduction of tracked vehicles reduced transportation

costs by 75 per cent and in the words of one contemporary,

"revolutionized winter transportation in this country." Thereafter the

company shipped by tractor exclusively.36

The revolution in overland transportation presaged by the use of tracked

vehicles constituted an advance of giant proportions when it is

considered that in the same year another miner, Robert Fisher, hauled

three tons of ore from his claim to Keno City by dog team, a distance of

17 miles. Treadwell Yukon added another caterpillar to its fleet in

1923; trucks were coming into common use and the superintendent of roads

was predicting that once "objectionable grades" on the Mayo-Keno road

had been removed, shipments of 70 to 75 tons could be handled on a

regular basis.37

During the 1923 season the territorial government concentrated its

road-building efforts on the 37-mile trunk road between Mayo Landing and

Keno City. Modern construction equipment was purchased and put to use

with "encouraging results." Treadwell Yukon and Keno Hill, the two

companies which stood to gain most from its completion, contributed to

the construction of the road. While not conforming to a uniform standard

in its entirety, the road was a major factor in reducing transportation

costs. Rates on freight delivered to Keno City from Mayo were cut from

15 cents a pound in 1920 to 5 cents a pound in 1923 exclusive of freight

hauled by track-vehicles which was cheaper still. Completion of the road

also led to a substantial increase in traffic movement during the summer

months. In 1927 Atyey tractor trailers superseded wheeled carriers for

summer use with a consequent increase in carrying capacity and less road

damage. By 1928 Mayo-Keno freight rates had levelled off at one to one

and one-half cents a pound depending on quantity.38

97 Tractors on Main Street in Mayo, bound for Wernecke Camp.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

98 Coping with the Yukon winter required ingenuity. This vehicle

probably bears little resemblance to what came off the assembly

line. The front wheels have been replaced by skis, the tires equipped

with tracks and the rear tire appears to have been grooved to

help anchor the tracks.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

If the introduction of caterpillers "revolutionized" winter transport,

the installation of a concentrating mill by Treadwell Yukon in 1924 was

tantamount to ushering in the millenium.39 Essentially,

concentration accomplished the same object as hand sorting but far more

efficiently. It involved crushing the ore, then subjecting it to

processes of clarification and flotation whereby the unit weight of the

end product, or concentrate, was greatly increased in value. Some idea

of the significant savings resulting from concentration is given by data

which show that the Treadwell mill reduced ore to concentrate in the

ratio of 10:1 to 15:1.40 Simply stated, this meant that ore slated for

shipment had increased in value ten-fold while transportation costs had

remained constant; or conversely, that transportation costs had been

reduced 90 per cent. Concentration solved another transportation

problem, at least for the smaller operators. It enabled them to sell

their ore to Treadwell Yukon for treatment and receive immediate

payment, instead of waiting for the smelter returns. In an industry

where it was impossible to extract, treat, transport, smelt and get paid

in a single season and where the market price of silver-lead could

widely fluctuate from year to year, this was a positive

boon.41

Installation of the concentrator marked a radical departure from

previous attempts to deal with the transportation problem. It

demonstrated that possible solutions to the problem were not confined to

the conventional answers of the past; refining existing modes of

transportation, developing new ones and improving access routes. It

portended an increasingly sophisticated approach which saw

transportation in terms of the economic viability of the territory and

fostered a realization that whatever facilitated the movement of people,

supplies and services, whether it be the designation of a new port of

entry, a telegraph or wireless or even the selection of a new capital,

entailed a legitimate response to the transportation

problem.42

In 1930 Treadwell Yukon expressed dissatisfaction with the arrangement

whereby it had shared a portion of Mayo road construction and

maintenance costs with the government. The

change was precipitated by the government's refusal to assist in

clearing snow from one of the company's roads after a particularly

heavy storm, and a rumour to the effect that roads used by tractors

would no longer be maintained. The government's decision in this regard

was particularly surprising in view of the fact that Treadwell tractors

had carried mail between Mayo and Keno that same winter without charge

when snow had prevented the regular contractor from operating his

trucks. Additionally, the company had improved certain sections of the

Mayo-Keno trunk road on its own initiative and at its own expense.

Company roads, moreover, assisted neighbouring operators and increased

the value of adjacent properties. Livingston Wernecke, the company's

general manager, argued that the "building of all roads," including

Treadwell Yukon's, was "a true and proper function of the Government,

either Federal or Territorial" and added that by not doing so, the

government was "side-stepping one of its functions; a function that is

extremely important to a new country."43

In response to Wernecke's charge, the government conceded that it was

"very difficult to take exception to the contention that the matter of

building roads is one for the Government"; nevertheless, it held that

deferment of the royalty tax on mineral production, which had not been

imposed until 1929, demonstrated that "the Government has in every other

possible way given assistance to the mining industry in the Mayo

district."44 There the matter died, though not to the

satisfaction of Treadwell Yukon. The controversy itself is nonetheless

important. It shows that the debate over the role of the government in

northern development is not a product of the 1950s as has generally been

assumed and it offers clear proof that roads are not a newly discovered

palliative for the problems of resource exploitation in the North.

By 1920 the condition of the Overland Trail had, in Mrs. Berton's words,

"greatly depleted." "There were fewer travelers to the mining camps

now," she wrote, "for the palmy days were over."

Many of the roadhouses which in the old days had been spotted every

twenty-two miles along the winter road were closed. Passengers now had

to provide their own lunches and these were eaten in the open after

being thawed out by a bon-fire on the side of the trail. In the old days

we had made the journey in less than a week. Now the stage only made a

post a day and, if the trail was bad, the trip often took longer than a

fortnight.45

In 1921 the White Pass and Yukon Route surrendered the winter mail

contract it had held for 20 years and terminated its Overland Trail

operations. The company had initiated winter hauling in the first place

to secure the mail contract for its sternwheelers. With

the failure of the Side Streams Navigation Company in 1918, the last

obstacle to complete monopoly on the Yukon waterways was removed and

with it any competition for the postal contract. The winter contract was

taken over by Coates and Kastner in 1921-22 and later surrendered

to Greenfield and Pickering, who were superseded in turn by Richards and

Phelps during the late twenties.46

99 A road grader packs the snow.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

100 A supply train drawn by a power toboggan.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

In the years preceding the successful establishment of the silver-lead

industry, Dawson had been the main supply centre and distributing point

for the Mayo camp. In 1913-14 a 40-mile wagon road was built from

the mouth of Hunker Creek to Flat Creek, from which a good winter road

was built to Mayo Landing.47 In the meantime, the Overland

Trail was rerouted through Black Hills and Scroggie to serve the placer

communities that had sprung up there.48 The advent of

large-scale silver-lead production, however, underlined certain

deficiencies in the existing overland transportation system.

Consequently, the Overland Trail was again rerouted to provide direct

communication between Whitehorse and Mayo. The Whitehorse-Minto section

was left intact, but at Minto the route was diverted northeast to Willow

Creek where it crossed the Pelly River some 30 miles above the site of

the old river crossing. From Willow Creek the trail was extended to

Crooked Creek which became the terminus of the main road. From there the

trail branched off to Mayo on the east and Dawson on the

west.49

Dawson's diminishing status as a metropolitan centre with an attendant

hinterland can clearly be seen in the diversion of the Overland Trail,

but Dawson's decline was not limited to the loss of its metropolitan

function. Throughout the 1920s the Dawson area steadily lost ground as

the territory's main economic region and in 1926 it was superseded by

the Mayo district. This decline was reflected in the flow of traffic

over the Overland Trail which by 1928 was moving in much greater

quantity over the Mayo division of the Overland Trail than its Klondike

counterpart.50

Route modifications were accompanied by technological changes in the

modes of transportation. In 1923-24 trucks replaced wheeled stages

for spring and fall travel while horse-drawn sleighs gave way to

caterpillars for winter use. These improvements were initially confined

to the Whitehorse-Yukon Crossing section of the Overland Trail, beyond

which the old modes of transportation were retained. According to Mrs.

Black, caterpillar operators were limited to two-hour shifts as "the

fearful lurching of the 'cat' over the rough trail rendered it

unbearable for a driver to work" for an extended period of time.

Occasionally Treadwell Yukon assisted the regular transportation company

by freighting supplies with its own tractors between Whitehorse and

Mayo.51

Despite these cumulative improvements, one obstacle continued to hinder

traffic movement over the trail. That obstacle was the river transfer at

Yukon Crossing, which J.S. McNeill described as "the greatest drawback

on the Overland Route." While the river generally froze over in late

November, the Yukon Crossing section remained open for another month,

after which it had to be tested regularly for rotten ice. The cable

carrier that had been erected in 1916 to facilitate the transfer of

freight, passengers and mail between Whitehorse and Dawson during

freeze-up and break-up had a limited capacity and canoe transfers had to

be reinstated to handle the traffic increase resulting from Mayo.

Interdistrict overland transportation did not progress beyond the

seasonal role it had historically played during this period. The

Overland Trail was a complement to water transportation and was not

maintained during the season of open navigation. The trail fell into

disuse in the late 1930s following the inauguration of regular air mail

service. Without the mail contract "no continuous freighting service by

trail would pay" and, as a consequence, the Overland Trail was

virtually abandoned as a commercial highway.52

The depression had a twofold impact on the territorial economy which was

by no means entirely negative. The silver-lead industry was severely hit

by the crash in base-metal and silver prices although this was chiefly

felt, at least in the beginning, in a drastic reduction in ore reserves

rather than a precipitous decline in production. In its annual report

summarizing 1930, the Department of Mines noted that "an ore that was

profitable a year ago can no longer be considered as ore; the minimum

content of silver necessary for profitable operations has nearly

doubled." Before the crash Treadwell Yukon had estimated its ore

reserves to be "as great as at any time during the development of the

camp." A year later the company announced that "the ore in sight in its

properties was sufficient to last only two and a half

years."53

The smaller operators in particular were vulnerable to the vicissitudes

of the depression. Lacking the capital to increase the value of their

ore through concentration, many were forced to abandon production. For

them, development and assessment work were all that the forseeable

future held in store. A few were fortunate enough to have located on

rich properties which could be worked by hand sorting, but the

Department of Mines predicted that "production from these sources will

be very small."54

After exhausting its properties on Keno Hill in 1932, Treadwell Yukon

closed its concentrating mill and abandoned Wernecke camp. Operations

were then resumed on Galena Hill where mining continued on a much

reduced scale. In the absence of an operational concentrator, the

company was forced to resort to hand sorting which in large measure

accounts for the diminishing returns recorded from 1933 to 1936. A great

deal of effort was expended on development work during this period,

however, which resulted in the surprising discovery of an extensive ore

deposit on Galena Hill in 1936. When it is considered that this same

property was reported "exhausted" after the 1934 season, the vagaries of

mining become apparent. The company transferred its concentrating plant

from Keno Hill to Elsa in 1935 and full-scale production was resumed in

1936.55

Gold mining, on the other hand, was given a substantial impetus by the

depression. Falling prices in other sectors of the economy had the

effect of increasing the purchasing power of gold, the price of which

remained constant until 1934 when it was revalued upward by the United

States government to $35 an ounce.56 The Yukon Consolidated

Gold Corporation was completely reorganized and finally established on

a firm footing through a series of litigative actions that culminated in

the removal of A.N.C. Treadgold57 As a consequence,

full-scale systematic production was resumed after an hiatus of some 20

years with the result that in 1933 the Klondike regained its primary

position in the Yukon economy.58

Despite the re-emergence of the Klondike and the transfer to Galena Hill

by Treadwell Yukon, few roads of any consequence were built during the

1930s. A road was constructed between Keno Hill and the Silver King claim

group on Galena Hill, while in the late thirties work was done on a road

connecting Dawson with the Alaska boundary near Eagle, Alaska. Most of

the activity of the territorial roads department was directed toward

maintaining or improving existing roads, a sizeable task in

itself.59

This did not silence the persistent Yukoners for whom roads were a

universal panacea. "What my constituents are more interested in,"

George Black declared, "are roads, for in so vast a country transport

is a vital problem." During the late thirties some federal funds were

made available for road building as part of a national public works

programme, but this failed to satisfy the insatiable appetites of those

in the Yukon who saw at the end of every roadway the proverbial pot of

gold.60

III

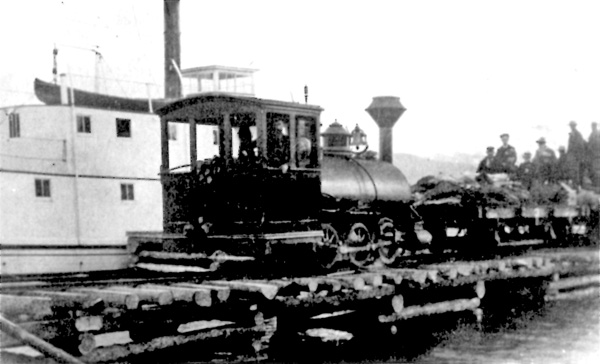

Before the rise of lode mining, the region tributary to the upper

Stewart River had been little more than an outpost of Dawson.

Transportation routes, water as well as overland, had originated at

Dawson and the entire Mayo area had been supplied by trading and

transportation companies operating out of the then territorial capital.

During the first decade of the century, two sternwheelers,

the La France and the Prospector, owned by the Stewart

River Company, had made the run between Dawson and Mayo Landing carrying

passengers, freight and mail. Although the company continually reported

a loss at the end of each season, it persisted until 1909 when the

Stewart River trade was taken over by the Side Streams Navigation

Company. The Side Streams Navigation Company furnished weekly service

between Dawson and Mayo, a distance of 238 miles, during the open season

of navigation which generally ran from 20 May to 1 October. Freight was

delivered to Mayo Landing at a rate of two cents a pound. The Side

Streams Navigation Company survived until 1917 when it too succumbed to

the pressures of extended supply lines, a small market and insufficient

revenues.61

The British Yukon Navigation Company extended its operations to Mayo in

1918. Although Taylor and Drury of Whitehorse ran the Thistle,

and later the MV Yukon Rose, to supply its widely scattered

trading posts, the British Yukon Navigation Company now enjoyed complete

control over the Yukon waterways since Taylor and Drury was not a common

carrier. Moreover, with the exception of Carmacks and Mayo, where Taylor

and Drury had trading posts, the Thistle, and its successor, the

Yukon Rose, worked rivers such as the Hootalinqua, the Pelly and

the White in which the British Yukon Navigation Company had no interest.

In this respect Taylor and Drury played an important role which was a

throwback to pre-gold-rush days when trading and transportation

functions were frequently merged in one company, thereby enabling

transportation to be provided in remote areas.62

The expansion of the White Pass and Yukon Route into the Stewart River

region did not immediately diminish that region's dependence on Dawson.

Even after the establishment of the silver-lead industry in 1921,

Dawson remained a major funnelling point for river traffic into the Mayo

district.63 Until 1923 when the bulk of this traffic was

transferred to the upper river, bagged ore from the Mayo mines was

shipped downriver to Alaska for transhipment to a smelter in the United

States.

Most of this freight was handled by the American Yukon Navigation

Company, an American-registered subsidiary of the White Pass and Yukon

Route.64 Although the company made occasional trips to Mayo,

its operations were primarily confined to the lower river. As a general

rule, the ore was picked up at Stewart Landing or Dawson after having

been dropped by the company's sister subsidiary, the British Yukon

Navigation Company. "Improvisation was the important thing," a

company official explained. "What could be done with the boats

available, water conditions etc. were factors that had to be taken into

consideration."65

101 Thousands of bags of ore concentrate await shipment by boat

from Mayo.

(Photo by J. Dunn.)

|

102 The barge Ibex, loaded with concentrate, waits at

Stewart Landing to be transported to Whitehorse.

(Source unknown.)

|

In its annual report on mineral production for 1921, the Dominion

Bureau of Statistics reported that "complete development [of the Mayo

deposits] would of course be obtained by linking up the mining area with

the White Horse Pass [sic] and Yukon Route at

Whitehorse.66 The bureau was not alone in recognizing the need

for a shift away from Dawson. The transportation company was cognizant

of the deficiencies of the existing water route. Landing facilities at

Dawson were so poor that it was often impossible to dock loaded vessels

at low water. The waterfront area was congested with silt from dredging

operations on the Klondike River. This was exacerbated by an eddy on the

right limit of the Yukon River that encouraged silt accumulation and

prevented the normal wash of the current from dispersing the sediment.

Extending the wharves was not feasible because of the danger of ice

damage during the spring break-up. Since no long-term solution was foreseen

and as dredging the waterfront was never seriously considered, the

British Yukon Navigation Company was forced to take action of a

temporary and continuing nature. On or about 15 August of each year

during a period of low water, the company would withdraw certain of its

sternwheelers from service and use them to sluice out the reservoir of

sediment with their paddle-wheels, a procedure that was then repeated

every few weeks until the end of the navigation season. This was not

entirely successful, however, as the sluicing paddlewheels tended to

leave deep holes in the riverbed, thereby creating new pockets for the

silt to accumulate.67

In spite of these drawbacks, most of the ore was shipped via Dawson

until 1923. Although the Mayo-Whitehorse waterway was substantially

shorter, the White Pass and Yukon Route assumed that "it would be

impossible to send this ore up to Whitehorse from the mouth of the

Stewart River as the Yukon [River] above Dawson to Whitehorse was a much

swifter stream than below Dawson. The development of a barge

specifically designed for swift-water use, however, enabled the company

to establish regular river service between Mayo and Whitehorse with

connecting rail service to Skagway in 1923.68 In the meantime, the

American Yukon Navigation Company had curtailed its operations on the

lower river. The completion of the Alaska Railroad from Seward to

Fairbanks in 1922 by the United States government caused the American

Yukon Navigation Company to suspend its Dawson-Saint Michael operation

in exchange for a quid pro quo whereby the United States government

refrained from running boats into the Yukon Territory from

Nenana.69

The change in transportation routes occasioned by the transfer of Mayo

traffic to the upper river had a serious impact on Dawson. Coupled with

the competition arising from the Alaska Railroad,

tonnage through Dawson decreased to such an extent that after 1923 the

American Yukon Navigation Company maintained only one sternwheeler on

the Dawson-Nenana run. This vessel was primarily engaged in moving ore

not handled on the upper route and did not maintain a regular schedule.

In 1923 the company reported a net operating loss of fifty thousand

dollars. The following year the general manager of the White Pass and

Yukon Route minced no words in describing the business outlook in Dawson

as "bad," appending this observation with a request for a drastic

reduction in waterfront leases under a veiled threat of pulling out of

the city if the request were not granted.70 Unfortunately for

the company, no immediate relief was obtained, but, despite its threat,

it carried on.

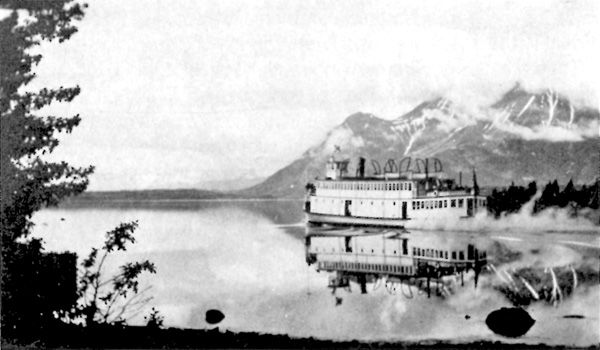

While continuing to function as the territory's main highway of trade

during the twenties and thirties, the Yukon River became increasingly

dependent on one of its tributaries, the Stewart River, for the vital

infusion of products — silver-lead ore from the Mayo mines —

required to sustain that trade. The Stewart, a 320-mile stream rising in

the headwaters of the Mackenzie Mountains, conformed to the pattern

established by other northern and eastern tributaries of the main

watercourse in that it was fed by precipitation rather than glacial

melt.71 This peculiar condition made through-navigation

between Mayo Landing and Whitehorse impossible for all practical

purposes as high- and low-water levels were not uniformly distributed

throughout the Stewart-Yukon system. Because of this phenomenon, the

British Yukon Navigation Company handled traffic between Mayo and

Whitehorse in two stages. Bagged ore from the mines was loaded onto

sternwheelers and barges at Mayo and conveyed to Stewart Landing where

it was transhipped by vessels on the regular Yukon River run. During

late May and early June when the Stewart reached its highest level, the

company assigned its larger boats to the task of moving as much ore as

possible between Mayo and Stewart Landing. That ore which was not

immediately transhipped was stockpiled until the Yukon River achieved

sufficient depth, generally after 1 July, to permit backlog shipments

to the railhead at Whitehorse.72

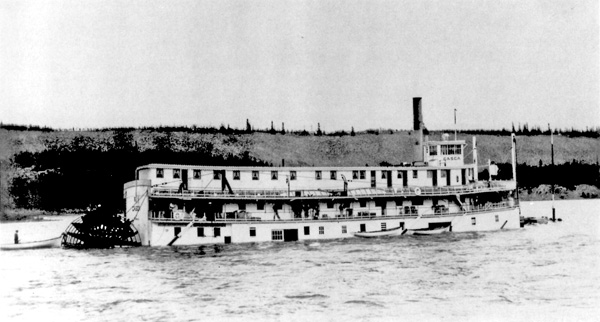

103 The SS Keno winching off a bar with a "walking stick"

or spar. Designed for the Stewart River trade, the Keno

was built in 1922. Its hull was rebuilt in 1937. The recess in

the boat deck gave the wheelman an unobstructed view for the

for'deck and the river and was originally required because the

Keno's hull was short in relation to its housework.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

A shifting navigation channel and prolonged periods of low water,

each characteristic of the Stewart River, underlined the need for a

specially designed vessel capable of operating within the limitations

imposed by the river and able to meet the transportation demands of the

lode-mining industry. These requirements were in large measure satisfied

by the construction and launching of the SS Keno in 1922.

Designed especially for low-water use, the Keno was a

single-stacked sternwheeler 130.5 feet long and 30 feet wide. It had a

very light draft, an essential criterion for Stewart River operations.

Although it had facilities for 32 passengers, the Keno was

primarily a cargo hauler. When water ran high on the Stewart, the vessel

was transferred to the Hootalinqua River or Teslin Lake. During the 1924

season, the British Yukon Navigation Company operated the Keno

and two sister ships, the Canadian and the Nasutlin, on

the Stewart River, as well as two gas-driven motor launches, the

Hazel B and the Neecheah. By 1928, however, the river was

served almost exclusively by the Keno.73

The use of smaller sternwheelers on the Stewart River was only one

phase in a continuing battle between the British Yukon Navigation

Company and the river. Riddled with rocks and bars, the Stewart remained

a difficult river to navigate despite the utilization of the

Keno. Until the end of the steamboat era in the territory, the

Stewart was considered much harder to navigate than the Yukon. Some

skippers actually preferred the Stewart to the Yukon because of the

constant challenge it presented; however, deck-hands were almost

unanimous in their condemnation of it and many eyed their Yukon River

counterparts enviously. According to G.B. Edwards, the general manager

of the White Pass and Yukon Route, 14 sections of the river between

Mayo and Stewart Landing required lining, making "it necessary to reduce

the cargoes down to a mere trifle." In 1922 the territorial government

received a request to construct lining cables at various locations and

to remove the most menacing boulders on the watercourse. Later that

year, improvement work was undertaken on the 20-mile stretch of river

west of Mayo entailing rock removal, buoying sandbars and taking

soundings. In 1923, cables were installed to facilitate navigation at

Twentysix Mile Bar, Jackman's Chute, Long Line Bar, the lower end of

Long Line Bar and five miles above Porcupine.74

By 1929 the territorial economy had expanded into the upper Stewart

region. This region, situated north of the Stewart River above Mayo, was

an important centre for exploration, prospecting and trapping. The Mayo

district derived much of the timber required for its mining operations

there and the region was an important mineral area in its own right

because of the Beaver River silver deposits. While the possibilities of

the upper Stewart were variously described as "many" and "promising,"

access was difficult. Two sections of the Stewart River, the only water

route into the region, were particularly formidable. Fraser Falls, 43

miles above Mayo, effectively blocked all further sternwheeler

navigation. A half-mile portage was required to get above the falls

where supplies were transferred to small motor launches for the balance

of the journey. Although a tramway was proposed to facilitate the

handling of goods around the falls, it was never constructed. At

Three Mile Rapids, so named because they were located three miles above

Fraser Falls, the launches had to be tracked through. In the spring of

1935 the rock formation on the left limit of the rapids was blasted and

removed, thereby enabling the boats to negotiate the rapids under their

own power.75 Despite these improvements, river navigation

remained an arduous undertaking; in fact, the upper Stewart country

holds the unique distinction of being the only place in the territory

where overland transportation was not markedly inferior to river

transport before 1950.

Many of the improvements to the Yukon River in this period were made in

response to the demands of Mayo industry. Low water during May and June

impeded the movement of silver-lead ore, disrupting through transport

between Mayo Landing and Whitehorse. To a large extent the product of

the Yukon's glacier-fed tributaries, this low-water condition was

exacerbated by the slow break-up of shore ice on Lake Laberge. Shallow

flats at the upper end of the lake were also a factor in delaying the

opening of navigation. As early as 1916, Herbert Wheeler, an employee of

the White Pass and Yukon Route, had recommended that a channel be

dredged through the flats in order to advance the opening of the

navigation season. But his proposal, coming as it did before the

silver-lead industry had been established, lacked sufficient urgency to

be taken up.76

With the beginning of large-scale extractive operations during the early

twenties, a solution to the problem of low water became urgent.

Believing "that unless something could be done... the development at

Mayo would be retarded," the British Yukon Navigation Company

constructed a dam seven miles below Marsh Lake in 1925. Consisting of a

submerged weir with flashboard, the dam was built at a cost of $160,000,

the entire sum being borne by the White Pass and Yukon Route. At the end

of each navigation season when the rivers and lakes above the dam were

close to their high-water levels, the dam was closed. A minimum flow was

maintained throughout the winter for domestic use and fire control in

Whitehorse. Designed to retain a 13-foot head at the site, the dam

created a winter reservoir extending back to the southern end of Bennett

Lake that was five feet above dead low water. After 1 May the dam was

progressively opened to flush out the ice on Lake Laberge and to raise

the level of the Yukon River. An outstanding success, the dam effected a

20 to 25 per cent increase in the carrying capacity of the Yukon River.

It advanced the navigation season by some three weeks at a most

propitious time, when long hours of summer sunlight permitted 24-hour

operation of the river boats, enabling at the same time the first boats of

the season to carry full loads.77

104 The British Yukon Navigation Company dam at Marsh Lake.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

105 The lampblack trail on Lake Laberge.

(Photo by W. Bamford.)

|

106 The steamer Casca plows through the lampblack trail.

(Photo by W. Bamford.)

|

Another technique developed by the transportation company to hasten the

melting of ice on Lake Laberge consisted of spreading a mixture of

carbon black, old crankcase oil and diesel oil in a series of strips

across the length of the lake. The mixture was sprayed from the back of

a truck, the operation being so timed that the application was done in

clear weather and while the ice was still solid enough to support the

truck. The expediency of the technique depended, Wheeler later recalled,

"on whether we get a heavy fall of snow after it has been spread or

whether we get continuous clear weather with consequent sunshine," as

surface snow inhibited the melting action of the sun upon the mixture.

Despite this measure of unpredictability, the treatment was capable of

opening a channel through three feet of ice under optimum climatic

conditions.78

Navigation channels on the Yukon River were modified annually by the

movement of gravel, silt and rocks during the spring break-up. At the

beginning of each operating season the company would employ two small

gas boats, the Sibilla and the Loon, to chart the most

navigable channels on the waterway. Where necessary, the riverbed was

raked or scraped to open clogged or closed channels. In 1928, for

example, the channel through Hellsgate was scraped with a dragline

powered by a donkey engine. While this method achieved satisfactory

results, it was costly, provided temporary relief only and caused

serious delays to passing sternwheelers, Pile and rock dams designed to

divert water into the main channel proved inadequate as well, as the

water tended to cut around the ends of them.79

In addition to regular improvement work, the company employed

artificial means to control the flow of traffic over the river. This was

done with a commodity- and class-rate system designed to stimulate or

retard the movement of freight as conditions demanded. During periods

of low water when heavy freight could not be shipped and thus entailed

storage in the company's Whitehorse warehouses, high class rates were

applied to discourage shipments. The opposite was true of course during

high-water periods when commodity rates were in

effect.80

As far as the British Yukon Navigation Company was concerned, the best

available solution to the channel problem was to dredge out as permanent

a channel as possible on the Yukon and Stewart rivers. In 1929 the

territorial authorities, cognizant of potential competition for Mayo

traffic from Alaskan ports, requested a grant from the Department of the

Interior to finance a dredging project, warning the department that

"unless navigation on the upper river is improved... a large portion of

this traffic will eventually go down the River to Alaska." After

consulting the Department of Public Works, which declined to fund the

project, the Department of the Interior notified the gold commissioner that no

assistance could be expected from Ottawa.81

In return for constructing the Marsh Lake dam, the British Yukon

Navigation Company received an annual grant from the territory to

defray the cost of general improvement work on the Yukon's navigable

rivers.82 The company considered the grant to be "niggardly,"

noting that more money was spent on the less-travelled Stikine. As the

territory's sole transportation company, the White Pass and Yukon Route

felt that it understood the transportation needs of the Yukon better

than anyone else. Such government-sponsored schemes as the

Carcross-Whitehorse road, which ran almost parallel to the railway, were

viewed with a considerable degree of skepticism when the waterways

demanded so much attention.83 The company had a vested

interest in seeing government money expended on navigation improvements

as overland transport, owing to the increase in motor vehicle use, was

becoming progressively more competitive with river transport,

especially on certain types of goods.

Barges, the primary mode of conveyance for Mayo ore, contributed to

the high cost of shipping. Company officials estimated that pushing a

barge added 50 per cent to a sternwheelers operating time with a

consequent increase in fuel consumption.84 In an attempt to

reduce barging on the Stewart Landing-Whitehorse section of the Yukon

River, Herbert Wheeler, the president of the White Pass and Yukon Route,

and Bert Fowler, the shipyard foreman, designed a sternwheeler that

could carry three hundred tons, a greater freight-carrying capacity than

any other boat on the upper river. Constructed in the company's

Whitehorse shipyard and christened the SS Klondike, the new

sternwheeler was launched in 1929. The Klondike, 210.25 feet long

with a 42.1-foot beam, was, like its sister ships, a light-draft

craft.85 Although many of its mechanical fittings had once

seen service on other Yukon river boats, two features which made the

Klondike unique on the upper Yukon were a specially designed hull

which fed a maximum flow of water into rather than around the

paddlewheel and compound condensing engines. The former modification

permitted efficient wheel-blade operation in shallow water even when the

Klondike was operating at full capacity.86

The Klondike performed ably. From Stewart Landing, where

silver-lead ore was hand-trucked onto the Klondike's cargo deck,

the upstream run was completed in the same time as a sternwheeler

operating without a barge.87

The 1930s were difficult years for the British Yukon Navigation

Company. The collapse of silver-lead production, reaching a low of 110

tons in 1935, led to drastic decline in transportation revenues.

Although gold production was increased substantially after 1932, the

transportation requirements of the Klondike district remained relatively

static. In an effort to reduce operating expenses, the company conducted

experiments with coal-fueled boilers; however, boilers did not function

well with this type of fuel and, as a consequence, wood-burning systems

were retained.88

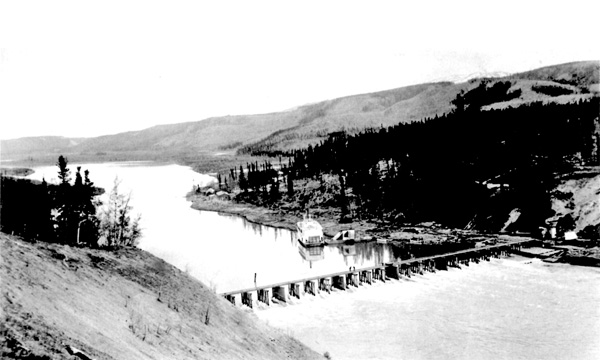

107 Steamer Aksala and barge approaching Five Fingers

Rapids on the upstream run.

(Photo by S. White.)

|

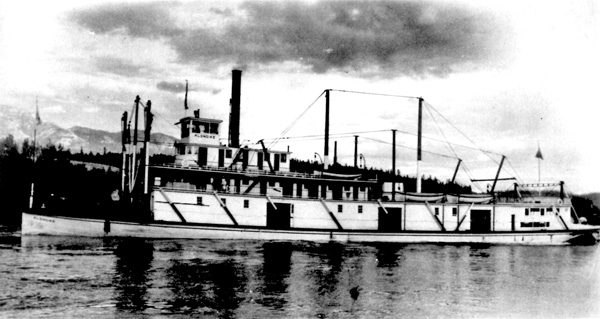

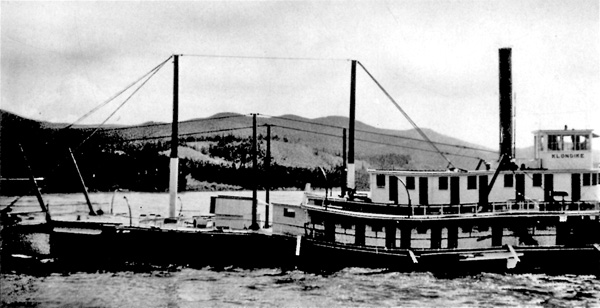

108 SS Klondike No. 1, 1929. The Klondike's

housework was kept to a minimum, all emphasis being placed

on cargo capacity without sacrificing shallow draft.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

In 1936 the company suffered a severe blow when two of its

sternwheelers, the Klondike and the SS Casca, were

wrecked. Fortunately, the disaster occurred at a time when silver-lead

production was at an extremely low level, thereby diminishing the impact

of the loss on Mayo shipments. Both were rebuilt in 1937,

Klondike No. 2 being slightly smaller than its predecessor. White

Pass officials have since maintained that reconstruction costs placed a

serious strain on the company's resources and that this, combined with

manpower and material shortages during the late thirties and the Second

World War, prevented the company from properly maintaining its

sternwheeler fleet. Interviews conducted with shipyard personnel lend

little credence to this claim, however, and the annual reports filed by

the steamship inspector leave no doubt as to the worthiness of operating

British Yukon Navigation Company boats.89

Between 1914 and 1939 the Yukon transportation system retained its

intimate association with the navigable waterways. Although the time

had long since passed when the movement of freight was confined to the

summer months, a seasonal pattern to transportation persisted that was

directly attributable to a dependency on water routes. The location of

supply centres and distributing points, moreover, continued to be

determined in large measure by their proximity to main water routes as

is evident from the following exchange. In 1923 a proposal was put forth

to relocate the office of mining recorder from Mayo Landing to Keno

Hill, the centre of extractive operations for the entire district. In

refusing to counsel the move, the Northern Affairs Branch of the

Department of the Interior cited as its main objection the fact that

"[as the Stewart] river is the general means of communication in this

district it might be a mistake to remove the office from the river and

from the point at which transhipment of ore is taking

place."90

The most important single factor governing water transport between

the wars was mineral production from the Mayo district. The demand for

transportation created by the lode-mining industry sustained the British

Yukon Navigation Company through what was otherwise a very difficult

period. As a revenue-producing source, moreover, silver-lead ore was far

superior to gold. Whereas one ton of silver-lead ore or concentrate was

equal in value to an estimated four to five ounces of gold, the return

to the transportation company on the latter was negligible in comparison

to the revenues realized from shipping the products of the Mayo mines.

Tonnage statistics recorded by the White Pass and Yukon Route show that

on the average twice as much freight was handled between Mayo and

Whitehorse than between Whitehorse and Dawson during those years when

the Mayo mines operated at or near capacity.91 As one writer

has noted, "without the Treadwell mine contract the regular sternwheeler

schedule would have been reduced to occasional supply runs to

Dawson."92 Mayo industry and the British Yukon Navigation

Company were mutually supportive. Neither could have functioned without

the other. Just as the transportation company was dependent on

silver-lead for vital revenue, so was the mining industry dependent on

the river facilities of the British Yukon Navigation Company for getting

its ore to the smelter.

But this dependence on water transport had many limitations. The

seasonal nature of river navigation forced Treadwell Yukon to maintain

on-site inventories that were far larger than those stocked by

comparable silver-lead producers operating in Quebec and British

Columbia.93 Because the transportation season was confined to

5 months of the year, the company often had to wait a full 12 months

before returns from the previous year's work were received. As a

consequence, investments in working capital were necessarily large with

attendant high interest charges. The instability of silver-lead prices,

which were subject to wild fluctuations on the market, meant that local

producers operated under the added burden of never knowing what they

would receive for their ore. Water transportation was deficient in

another very important respect. It precluded speculative production

increases on the basis of market trends. In August 1929, for example,

the territorial gold commissioner, G.I. MacLean, wrote that "if we had

adequate transportation the output [from the Mayo mines] would be very

materially increased, but when the White Pass can only handle a certain

tonnage each year, there is no advantage in increasing the output beyond

that figure."94 Ironically, the collapse in silver-lead

prices that was just around the corner would have deterred production

increases anyway. Nevertheless, MacLean's statement clearly underlined

one of the basic drawbacks of water transport — its inability to

adjust to rapid and substantial changes in demand.

109-110 In 1936 the British Yukon Navigation Company lost Casca

No. 2, which foundered in Rink Rapids (Fig. 109) and Klondike

No. 1, which hit a rock five miles below the confluence of the

Yukon and Hootalinqua (Teslin) rivers (Fig. 110).

(Photos by

J.J. Forde and from the Maritime Museum, Vancouver.)

|

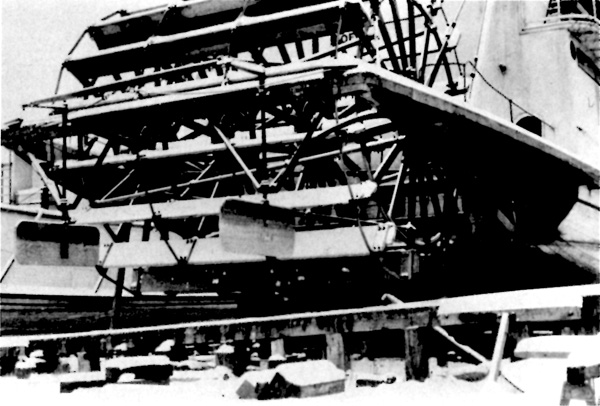

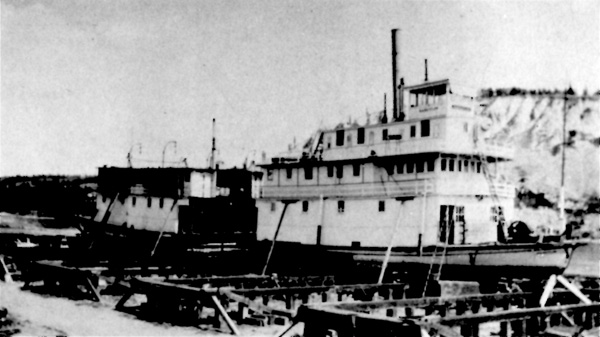

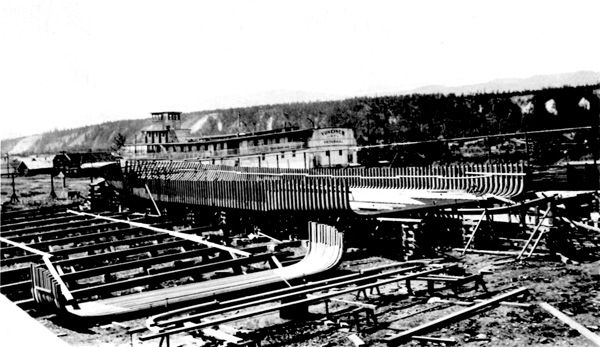

111-116 The shipyard at Whitehorse. 111,

The wheel of the Aksala. (Photo

by R. Kingston.) 112, To enlarge the

Nasutlin, boatwrights cut it in half and added a middle section.

The shipyard crew called it the "Nasutlin stretch." (Photo by S. Smith) 113, The building of Klondike No. 2. The

boiler from the steamer Yukon) (background) was used in

Klondike Nos. 1 and 2. (Photo

by S. Smith.) 114, A crew removing ice

from the spillways. (Photo by W.

Crawford.) 115, To launch the boats in

spring, "butter boards" were fitted to the ways and the boats were

lowered onto these from cribs. Tallow was then liberally applied to the

ways. (Photo by H. Perchie.) 116, When the signal was given, the boats were

launched. (W. Bromley

Collection.)

|

117 Alaska Air Expedition planes in Dawson, 17 August 1920.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

IV

While the era of the dog sled and canoe had long since passed into

history, no new advance in Yukon transportation had ever overcome the

twin handicap that was as old as Yukon transportation itself; extended

supply lines and slow modes of travel. During the 1920s this twin

handicap was effectively challenged by an entirely new form of

transportation — the airplane. Unlike other forms of transportation

such as the sternwheeler, the railroad and the automobile, the airplane

found its first Canadian civil application in the North.

The North's unique role in the early history of Canadian aviation was

in large measure the product of a fortunate set of circumstances.

Postwar demobilization had left the country with a large surplus of

aircraft totally "unsuited to inter-city traffic either for passengers

or goods," but easily "adapted both to the conditions and needs of

aviation in the north." The North abounded in lakes and rivers that

provided ready landing sites for ski- and pontoon-rigged aircraft except

for those periods when the ice was forming or breaking up. These natural

landing facilities were crucially important during the pioneer phase of

development as man-made landing strips were economically

unfeasible.95

Much of the early interest in northern aviation originated with the

Canadian government. Following the war, the government conducted an

extensive inquiry into the potential of air transport in the North. The

response of several mining companies and a number of government

departments was favourable enough to justify further study with the

result that the Canadian Air Board was established in 1919. During its

brief existence the board did much to foster the development of northern

aviation through such undertakings as its aerial survey programme.

Unfortunately, the Department of National Defence, which assumed

responsibility for aviation when the board was abolished in 1923, was

less attuned to the northern possibilities of the airplane and

government interest in promoting northern aviation soon

diminished.96

Despite the government's early encouragement of northern aviation,

the first airplanes to reach the Yukon were not Canadian but those of

the First Alaska Air Expedition, an American-sponsored venture to

determine the feasibility of establishing an air route between Alaska

and the United States. Consisting of four, two-seater De Havilland 4Bs

piloted by eight U.S. Army Air Corps pilots, the expedition left New

York on 15 July 1920 for Nome, Alaska. On 16 August the planes made a

scheduled stop at Whitehorse, thereby becoming the first aircraft to

land in the Yukon territory. A day later they flew on to Dawson where

they were greeted by an exuberant crowd and the commissioner of the

territory, G.P. Mackenzie.97

The local inhabitants were quick to grasp the significance of the

expedition. They recognized that the airplane represented a practical

solution to their isolation. The air, unlike the rivers, the roads and

the railroads, provided an unlimited medium of travel free of shallows,

narrow channels, ice, grades, permafrost and drainage. At Dawson the air

corpsmen presented the commissioner with a petition from the citizens of

Whitehorse. The petition expressed the "fervent hope that our Government

will keep pace with other countries in the establishment of a regular

aeroplane service throughout our Dominion and especially in the Yukon

where it is so much needed."98

Despite these very significant early advances, six years were to elapse

before air transport was established in the territory. The abolition of

the Canadian Air Board brought to an end the government's early interest

in aviation's northern orientation. In the interim, however, a variety

of small airlines continued to operate in the northern regions of the

central and prairie provinces with the result that the design and

technology of the airplane were rapidly improved. By the mid-twenties

aircraft with closed cockpits or cabins, high wings, air-cooled radial

engines and adaptable landing gear had been developed that were

well-suited to the conditions of northern flying.99

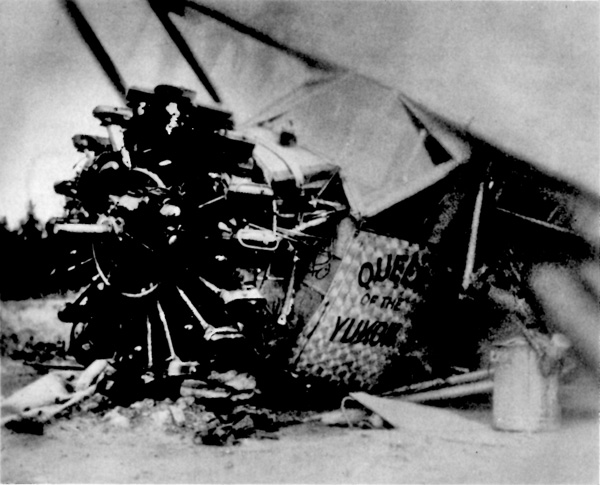

The first company to offer commercial air service in the territory was

the Whitehorse-based Yukon Airways and Exploration Company. Organized

in 1926 by a group of Mayo district and Whitehorse businessmen, Yukon

Airways commenced operations in the spring of 1927. The company's first

aircraft was a Ryan monoplane, appropriately named Queen of the

Yukon. The Queen had a payload capacity of twelve hundred

pounds or five persons and flew the Whitehorse-Dawson-Mayo circuit with

occasional side trips to Keno.100

Plagued by personnel problems, a lack of capital, crashes and poor

management, Yukon Airways succumbed in 1929. Its assets were taken over

by a group of Mayo district miners and businessmen and a new company

was incorporated in May of 1929 which retained the name of its

predecessor.

Prospects for the new company dimmed perceptibly when within the brief

span of five and one-half months it lost two of its three planes. In an

attempt to recoup, the owners appealed to the minister of the Interior

to rebate the $9,000 duty paid on the aircraft and requested the

short-term loan of a pilot and plane. During the negotiations with the

department the company lost its third plane and when the department

failed to proffer assistance, Yukon Airways was compelled to terminate

its operations.101

Despite the formidable problems associated with these early attempts to

establish Yukon aviation, the airplane had performed well enough to

justify a confident appraisal of its future role in the territory's

economic development. The mineral industry in particular was cited as a

potentially major beneficiary. As G.I. MacLean, the territorial

commissioner, wrote,

the airplane will... [enable] prospectors to

reach locations in a few hours and get down to a good season's work,

whereas, under present conditions practically all their time is consumed

in getting in and out of these places during the season of open navigation, and