|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 19

Yukon Transportation: A History

by Gordon Bennett

The Great Stampede

I

On 16 August 1896 gold was discovered on Bonanza Creek, a tiny

tributary of the Klondike River. As news of the discovery spread

throughout the territory, prospector after prospector, miner after miner

abandoned his diggings and set off in frenzied pursuit of the new El

Dorado. A year later Klondike hysteria enveloped the outside world.

In many respects the Klondike discovery and the stampede it fathered

provided a fitting curtain to the 19th century. Debilitating depression

with only brief and fitful interruptions had overhung the western world

for a generation before 1898. The psychological effects of the Klondike

discovery changed all this, precipitating an almost New Year's Eve type

of celebration of purge and promise, as the worn-out 19th century

indulged in one last grand binge. In an era that had been characterized

by the Gilded Age, the Great Barbecue and the Robber Barons, the chain

of events set in motion by the discovery served to democratize the maxim

that "money making was the most prized career."1 No longer

was wealth regarded as a private prerogative of a Rockefeller, a Morgan

or a Carnegie: the New Year's resolution on everyone's mind was to

strike it rich.

With unwitting foresight, a despatch datelined Forty Mile, Yukon

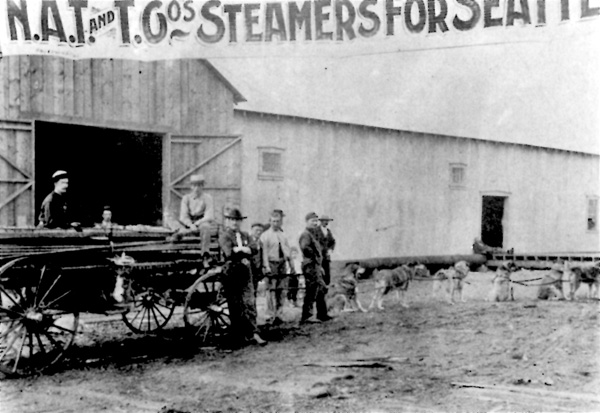

Territory, 17 August 1896, predicted that "such is the lure of gold in

depression ridden America that many are expected to come."2 Probably

no other event in Yukon history has ever been anticipated with such

understatement. From late July of 1897 when the Portland and the

Excelsior, each laden with gold, landed in Seattle and San

Francisco respectively, most of the English-speaking world and much of

Europe found itself caught up in a maelstrom that knew only two words

— "gold" and Klondike. Almost immediately a crush of humanity,

doggedly determined to win its fair share of untold wealth, streamed

north. Three factors made the Klondike gold rush possible: the existence

of a vast amount of placer gold, the publicity given to the

discovery in the press of the time, and the transportation system that

had evolved since the era of the fur trade.3 Without a

juxtaposition of the three in 1897-98 the gold rush would never

have reached the proportions that it did.

If one accepts the definition of transportation in its broadest sense

as the utilization of transportation routes and a variety of

transportation forms to move men and supplies, the history of

transportation during the gold rush can be said to have been practically

synonymous with the history of the gold rush itself. Each interacted

with the other; the one as cause, the other as effect as circumstances

dictated. If the gold rush is conceived, moreover, not as an independent

entity nor as a temporary aberration, but as one stage in the

historical evolution of the Yukon, then an estimate of its effect on the

transportation system can be attempted. With the exception of the

railroad, the impact of which properly belongs to a future chapter, the

gold rush did not substantively alter the nature or function of the

gateways which had been established prior to 1896. No new routes of any

consequence were discovered although several variations on the old

routes were used with varying degrees of success. What the gold rush did

do was to exaggerate the impracticality of the old Hudson's Bay Company

fur-trade routes and to strain and emphasize the inadequacy of the

coastal routes under gold-rush conditions. Where the effects of the gold

rush were most clearly felt were on the modes of transportation. As

might be expected, many of these effects were quantitative, but the

building of roads and tramways, the introduction of sternwheelers on the

upper river, and the construction of the White Pass and Yukon Route

railway were major qualitative changes in the transportation system of

the Yukon.

II

Another qualitative change which is not so immediately apparent also

occurred. Before 1896, no government had attempted to influence or

interfere with the transportation system. Adjustments in the

transportation system had resulted from the action of natural forces and

the response to them by individual men or trading companies. As we have

seen, this process of "natural selection" had resulted in the practical

extinction of the Hudson's Bay Company fur-trade routes, the domination

of trade by the Saint Michael route and the rise of the Chilkoot route

as the principal avenue of migration. With the gold rush, however,

government for the first time became actively interested in influencing

the flow of transportation into the Canadian North. The most conspicuous

examples of this interference were the promotion of the old Hudson's Bay

Company trade routes by the municipality of Edmonton; the promotion of

the Stikine railway project by the dominion government, and the

imposition of customs duties.

When news of the gold strike on Bonanza Creek reached the outside,

Edmonton was only a small town of seven hundred people. Nonetheless,

Edmonton qualified as a transfer point to the Klondike, being situated

at the head of a known trail to the Yukon (the old Hudson's Bay Company

Athabasca-Mackenzie-Porcupine-Yukon river route) and having the

facilities to serve as a supply base, in this instance the northern

terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway.4 In an attempt to

stimulate the economy, local politicians and merchants undertook an

advertising campaign to attract stampeders. Billing the route through

Edmonton as the "All Canadian Route,"5 they hoped to

capitalize on the patriotic inclinations of the Canadian stampeders. On

a more practical plane, the promoters emphasized the fact that "going

via Edmonton" eliminated customs levies, an important consideration for

those who had mortgaged themselves in order to take part in the rush.

Had Edmonton advocates been content to stand on this one advantage, the

Edmonton route would most likely have escaped the notoriety for which it

was later known, but the city built its advertising campaign around the

dubious assertion that the Edmonton trail was the fastest route to the

gold fields. Even the most ardent optimist would have been hard-pressed

to substantiate this claim for the truth of the matter was that the 90

days allowed for traversing the trail by the Edmonton promoters was

patently unrealistic.6 That some people took this route is

indicative of the delirium that overcame normally sane men during the

gold rush. The Hudson's Bay Company presence in the Yukon had always

been precarious, with transportation a basic problem. This obstacle, as

we have seen, was never successfully overcome. Moreover, to exacerbate

the plight of those who chose this route during the gold rush, the light

canoes, the assistance of Indians and voyageurs, the series of supply

bases, all of which had been available to the fur trader, were not

available to the gold seekers. Nor was there any resemblance between

traders who were capable of withstanding the rigours of the trail and

the stampeders who were not.

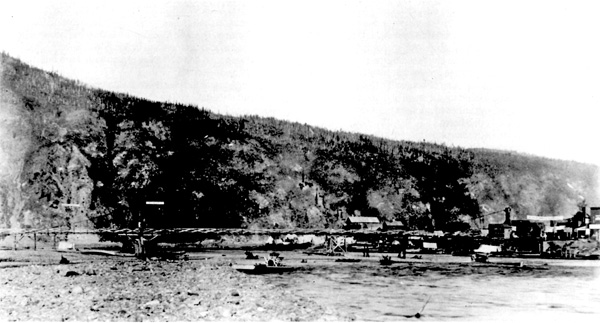

22 The first known view of what later became Dawson City — 13 years

before the discovery of gold on Bonanza Creek.

(Frederick Schwatka, Along Alaska's Great

River [New York: Cassell & Company (1885), p. 243.)

|

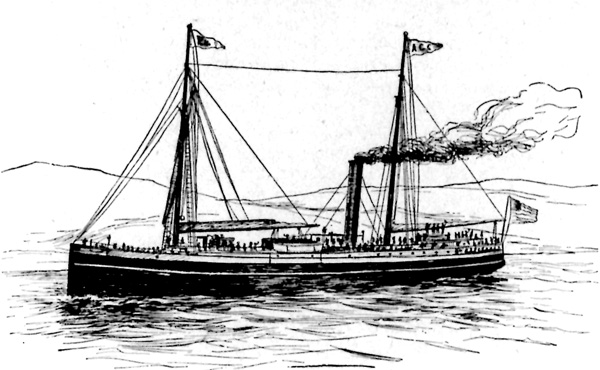

23 The arrival of the Excelsior (below) in San Francisco and the

Portland in Seattle in July 1897 signalled the beginning of the

great stampede.

(Chicago Record, Klondike [Chicago: Chicago Record

Co., 1897], p. 400.)

|

24 The Stikine route and main Edmonton trails to the Klondike.

(Map by S. Epps.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Of the one hundred thousand people who set out for the Klondike in

1897-98, only two thousand used the Edmonton route. Few of those

who did ever reached their destination. "Not a single one," Pierre

Berton has written, "as far as can be determined, found any gold at

all."7 In almost every case it took two years to go from

Edmonton to Dawson and by the time the lucky ones finally made it, the

gold fields had been staked from end to end. This first example of an

attempt by government, in this case municipal, to influence the

direction of transportation flow into the Yukon would have been comic

had it not had such tragic consequences. The overland routes running

west of the Mackenzie River proved no more responsive to the wishes of

Edmonton than they had been to those of the Hudson's Bay Company.

Edmonton was not the only would-be metropolis to vie for the Klondike

trade. Operating on the valid assumption that the great majority of

stampeders would opt for one of the coastal routes, the port cities of

Victoria and Vancouver, with the active support of Montreal- and

Toronto-based railroad interests, set out to supply the outfitting and

transportation needs created by the rush. In

this they were assisted by the Canadian government which imposed a

schedule of customs duties on all foreign goods going into the Yukon.

This schedule had the dual purpose of raising revenues and diverting

business away from such American centres as Seattle and San Francisco

which had early established a stranglehold on Klondike trade. As the

Yukon was cut off from the coast by the Alaska Panhandle, however, all

goods had to pass through American territory before reaching the Yukon.

There, supplies that had been purchased in Canada were liable to

retaliatory customs duties levied by American authorities, unless conveyed

through Alaska in bond, in which case any prior advantage gained from

outfitting in Canada was lost.

The trade issue was complicated by a longstanding dispute with the

United States over the Alaska boundary.8 Despite Canada's

claim that Dyea and Skagway, the coastal gateways to the Yukon interior,

were on Canadian soil, the United States exercised sovereignty over

both of them. Ever since the late 1880s Canada had pressed for a

solution to the question only to meet with American indifference. The

gold rush made a settlement all the more urgent from the Canadian

viewpoint for reasons of state as well as for the potential effect that

any settlement would have on the rivalry between Canadian and American

ports. The United States, on the other hand, showed little interest in

negotiating so long as it enjoyed de facto control over all supplies

going into the Klondike via the coastal routes.

An alternative solution to the boundary imbroglio presented itself

in the Stikine River route which originated at Fort Wrangell, Alaska,

followed the Stikine River to Telegraph Creek, crossed overland to

Teslin Lake on the British Columbia-Yukon border and thence down the

Yukon River system to Dawson.9 Under the treaty of 1825

between Great Britain and Russia, Great Britain had secured free

navigation rights on the Stikine which were ceded to Canada after

1867.10 The Stikine route, therefore, became a vital lever in Canada's

attempt to influence transportation flow into the Yukon, especially in

view of the failure to reach an accord with the United States on the

boundary question. The surveyor general of Canada succinctly explained

the need to develop the Stikine route. "We must have an independent

road allowing free access to our country whatever complications may

arise with the United States," he wrote, "and for this purpose it is

imperative that a road be located from Telegraph Creek to Teslin

Lake."11 With this in mind, the Canadian government signed a

contract on 26 January 1898 with those ubiquitous Canadian railroad

contractors, William Mackenzie and Donald Mann, to build a wagon road

within six weeks and a narrow-gauge railway by 1 September 1898 from the

head of navigation on the Stikine to

Teslin Lake.12 To complete the transportation system, the

government planned to connect each end of the rail line with a fleet of

steamboats.13 In return, Mackenzie and Mann were to receive a

land subsidy of 25,000 acres for each mile of line constructed. After a

long and occasionally acrimonious debate in the House of Commons, a bill

was passed approving the project.14 Twelve miles of track had

been laid and tickets had actually been sold when the

Conservative-dominated Senate rejected the terms of the government

contract. This dealt the coup de grâce to the Stikine project

and the railroad scheme was unceremoniously abandoned.15

Attempts to regulate artifically the flow of transportation into the

Yukon during the gold rush failed. Only in the imposition of customs

duties did the government achieve any partial success. This action may

have persuaded some to use the Edmonton route and it seems evident that

it was partly responsible for stimulating the trading and transportation

companies operating out of Victoria and Vancouver. The failure of

government to influence the selection of access routes to the Klondike,

however, appeared in sharp contrast to what was taking place, without

government intervention, on the traditional gateways of Saint Michael

and the Lynn Canal.

III

These two gateways, which attracted the majority of stampeders, were

linked to the West Coast outfitting ports by a thousand-mile stretch of

water known as the Inside Passage. As a result of the unprecedented

demand for coastal steamer facilities, the existing transportation

companies were strained to capacity.16 To cope with the

overflow, a number of new transportation companies sprang into

existence, coastal steamer production was rapidly increased, and old,

generally unseaworthy vessels that had been left to rot on the beaches

were revived, Martha Black, a towering figure in the post-Klondike

period of Yukon history, later described what for most of the stampeders

had been a typical trip up the coast when the gold-rush hysteria was at

its height.

The steamer was certainly a "has-been." She was dirty, and loaded

to the gun wales with passengers, animals, and freight. Men slept on the

floor of the saloon and in every corner. The captain was seldom, if

ever, sober, and there were many wild parties. Poker, blackjack, and

drinking went on night and day, and our safe arrival in Skagway was due

probably to the Guiding Hand that looks after children, tools, and

drunken men.17

The Saint Michael route responded to the gold-rush transportation

challenge with a rapid expansion in facilities. By the summer of 1898

there were an estimated 110 steamers on the lower river, a tenfold

increase over 1897 and a 14-fold increase over the pre-gold-rush

number.18 Saint Michael itself became something of a

boat-building or, more correctly, a boat-assembly centre.19

Yet despite the rapid increase in the number of boats on the lower

river, the Saint Michael route never did regain control of population

movement into the interior, a control it had lost to its Lynn Canal

rival after 1882. Though potentially the fastest route to the gold

fields, this advantage was never seized.

Several factors account for the lower route's failure to exploit the

opportunity provided by the gold rush. The transfer of traffic from

coastal steamer to river boat was not orderly. Passengers would be

spilled off the decks of the ocean vessels at Saint Michael only to

discover that there were no available sternwheelers to take them on the

last leg of the voyage to Dawson. This problem was exacerbated by

impediments to navigation on the lower river itself. On that section of

the river below Circle City known as "the flats," the river spread out

like a lake, cut through and through by innumerable bars and islands. As

a result, the river was reduced to little more than a series of small

shallow streams through which a pilot had to locate a channel

large enough to accommodate large steamers. Every summer once the

channel had been found, a pilot was stationed on the flats to take the

boats safely through, but the annual spring floods made it necessary to

locate a new channel each year.20 Initially the trading

companies had used Eskimos and Indians as deck hands and pilots because

of their knowledge of the river; however, their familiarity with the

watercourse was limited to short stretches and as a consequence 20 or

more native pilots were required for each trip. This system was

abandoned once white pilots had gained enough experience to navigate the

river without outside help, but the problem of shifting channels

remained.21

Another difficult section of the river was encountered at the

"Ramparts." At this point a sternwheeler running against the current

was forced to tie up every 10 or 15 minutes so that an extra head of

steam could be raised.22 At Fort Yukon, low water often made

it impossible to take a sternwheeler above the post.23 Had

the United States government acted upon the suggestion that a

permanent channel be dredged through the flats and at Fort

Yukon,24 the lower river might have attracted a great deal

more of the Klondike traffic than it did. However, while the lower river

route did not attract large numbers of stampeders, it did retain

important function that it had performed since 1869 as the life line to

the Yukon.25 Despite certain obstacles to navigation, it

remained the only feasible route over which heavy freight could be

brought in.26

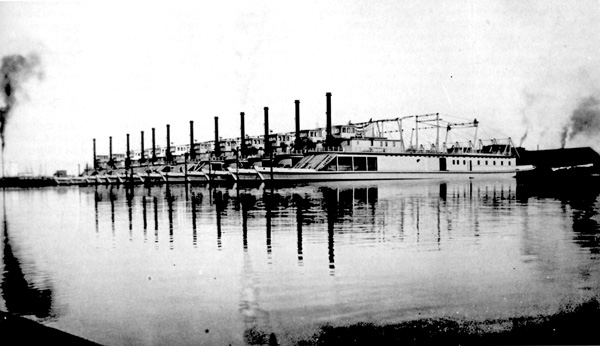

25 "Built by the mile and cut apart in proper lengths" — thus

did one observer describe the 12 virtually identical boats built by

the Moran Brothers shipyard in Seattle for the Klondike trade.

Included in this commercial armada were the J. P. Light, D. R.

Campbell, F. K. Gustin, Mary F. Graff, Pilgrim, Victoria, and

Oil City.

(Minnesota Historical Society.)

|

If most of the stampeders avoided the Edmonton trails and the Saint

Michael route with remarkable if unconscious discretion, they made up

for it by pouring onto the Alaska Panhandle with blitzkrieg force. It

was here that the mad cascade that constituted one of the largest mass

movements in peacetime history converged, only to be scattered upon one

of the six trails which led into the Yukon interior. Of these trails,

the most popular by far proved to be the trails over the Chilkoot and

White passes on Lynn Canal.27

Before the gold rush, the density of traffic over the Chilkoot Trail

had not been heavy enough to justify any major improvements.

Consequently, when the first wave of stampeders hit the beaches at Dyea

in August of 1897, the transportation facilities were wholly inadequate

to cope with the assault: a roughed-out road between Dyea and Sheep Camp

which required fording, a horse packing outfit that had been organized

in 1894 by John J. Healy28 and the human packing service

provided by the Indians. As a result, the stampeders were forced to

transport themselves and their supplies under the most adverse

circumstances. During late summer of 1897 many built canoes to move

their supplies up the Dyea River to the head of canoe navigation at

Canyon City, at which point everything was transferred to the trail

which led over the summit. When the river froze over, some sledded their

outfits over the ice to a point just below Sheep Camp.29 Most

of the stampeders, however, moved their supplies along the Dyea-Sheep

Camp trail that had been cut prior to the gold rush.

As the number of stampeders increased, some improvements became

necessary. A toll bridge was built one-half mile out of Dyea and a good

wagon road was constructed to Finnegan's Point, six miles outside the

city.30 Horses were brought into Dyea in great quantity and

packing operations were expanded. A number of communities sprang up

along the trail where the stampeders could stop for food and shelter,

only to disappear when the gold rush had spent itself and eliminated

their function.31

That winter the trail was improved when 150 steps were cut out of the

ice on the coastal side of the summit. Later more steps were added. A

cord life line was strung up parallel to this somewhat incongruous

stairway and shelves were hacked out at intervals so the stampeders

could avail themselves of a few moments' respite. A toll was levied for

the use of the steps which the operators collected without the

arguments commonly associated with such an enterprise. As T.A. Rickard

noted, "Everyone was in a hurry; and anything that facilitated progress

was liberally compensated."32 In December a horse-powered

tramway was constructed up the pass. It was superseded by a much more

ambitious undertaking in the spring of 1898. The new tramway,

which ferried goods from Canyon City to the summit and was later

extended to Crater Lake, was built by the Chilkoot Railroad and

Transportation Company. It consisted of a copper-steel cable supported

by tripods anchored in concrete and was powered by steam generators.

When it was finished, it was said to have "had the longest single span

in the world, twenty-two hundred feet from one support to the next."

Each car on the line had a 300-pound capacity. The tramway never

stopped and in the spring of 1898 it was dropping freight on the summit

at the rate of nine tons an hour.33

After the Chilkoot Railroad and Transportation Company tramway was

completed, the Dyea trail was equipped with a coherent transportation

system which eliminated most of the transportation problems that had

previously impeded the movement of traffic along this route. Freight

rates fell sharply, levelling off at 13 cents a pound for the through

journey between Dyea and Bennett;34 however, the impact of

this significant improvement was small. Ironically, by the time the

tramway became operable, the stream of humanity that had set out for the

Klondike the previous summer had practically dried up.

Since 1882 the Chilkoot Trail had been the funnel through which men

in search of Yukon gold had flowed. The gold rush did not change this. Of

the forty-odd thousand stampeders who are estimated to have made it into

the Klondike, well over half went in by this route.35 But

whereas before 1897-98 the Dyea trail had been regarded as the best

route to the Yukon gold fields, the gold rush had the effect of exaggerating

its deficiencies to the point where they overshadowed its utility.

Martha Black spoke for most of those who took the Chilkoot Trail during

the gold rush when she called it the "worst trail this side of hell."

"Men talked of the Chilkoot as if it were a malevolent thing," Kathryn

Winslow has written, "capable of wrath and punishment."36 Of all the

photographs taken of the gold rush, the one that depicted a black line

of lock-stepped humanity, stooped and bent as it inched its way through

the pass, came to symbolize this adversity.

Why did the gold rush so alter the reputation of the Chilkoot Trail?

Why did this transportation highway into the Yukon, heretofore regarded as the

best route into the interior, come to be regarded as some kind of hell

the stampeder had to survive before he was worthy of the Klondike

treasure? Was it the trail itself or something else that made men look

upon the Chilkoot as that "malevolent thing"? The evidence suggests that

a combination of factors, the stampeders themselves, the size of the

stampede, the season, as well as the inadequacies of the trail, wrought the

change. Few of those who set out for the Klondike in the fall of 1897

were fit enough to cope with the rigours of the trail. Fewer

still had any alpine experience. Improper diet and inappropriate

clothing for both the task and the climate added to the

hardship,37 but of all the burdens that each stampeder had to

face before he reached the Klondike, none was more significant in

altering the reputation of the trail than packing.

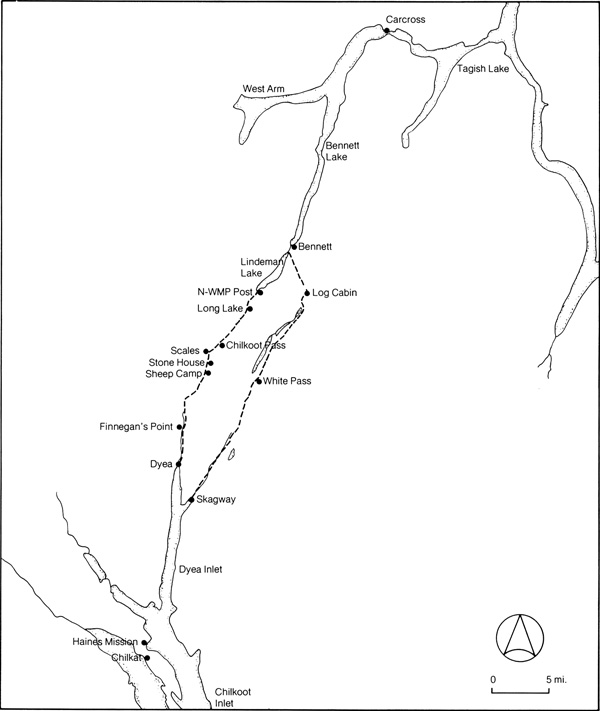

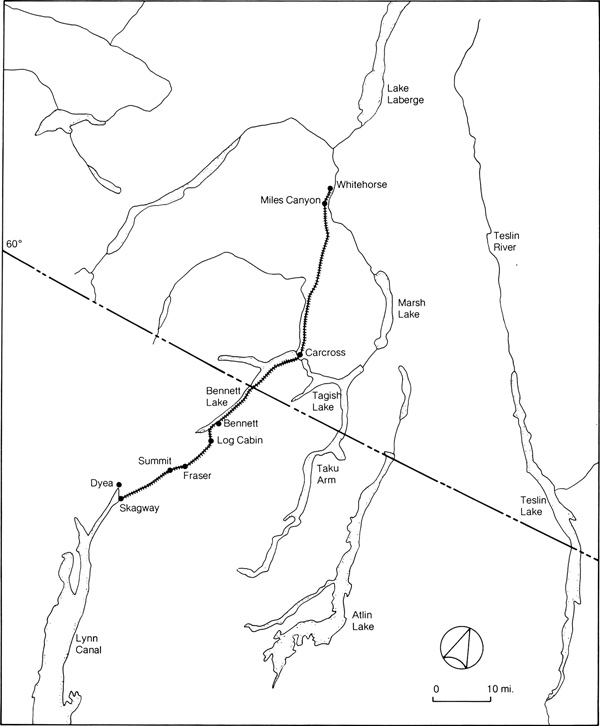

26 The Chilkoot and White Pass trails.

(Map by S. Epps.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

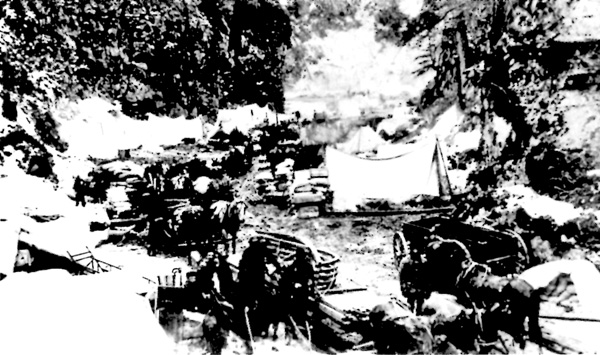

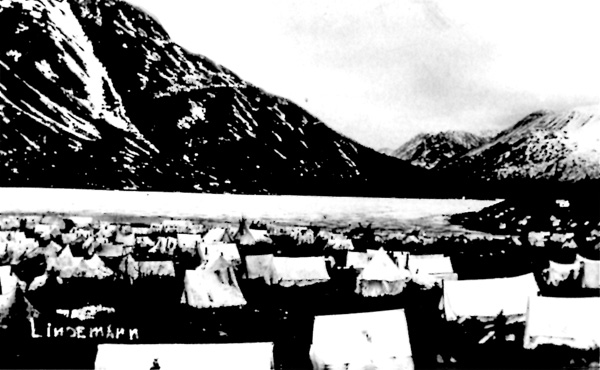

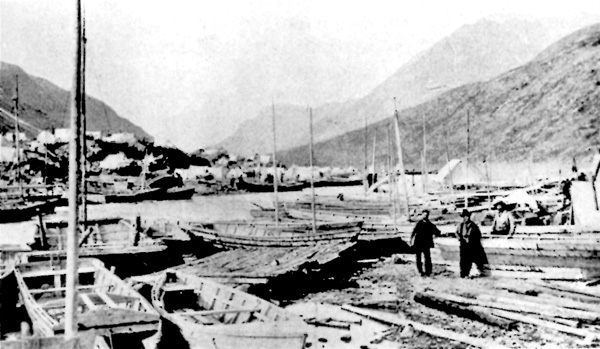

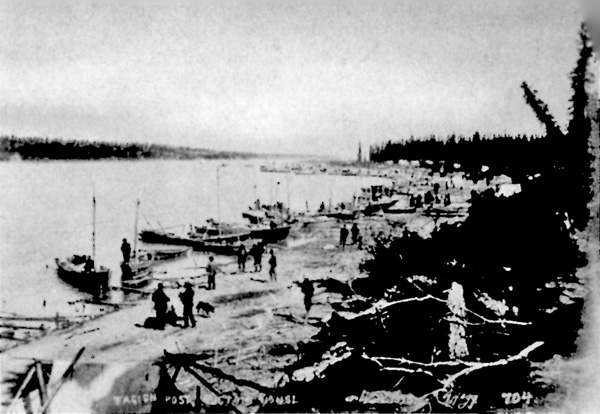

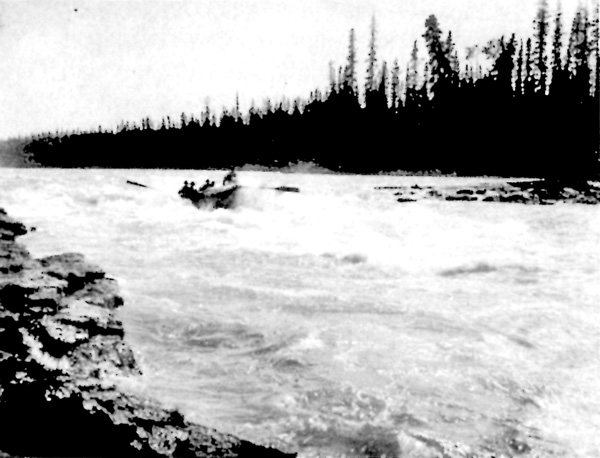

27-38 Few phenomena have been as well-documented

in photographs as the rush to the Klondike. Figures 27 to 38 show only a

few highlights. 27, A portion of the Skagway waterfront,

1898. (Public Archives of

Canada.) 28, The Chilkoot Trail

between Dyea and Canyon City. (Yukon

Archives.) 29, The Chikloot Pass

viewed from the scales. (Yukon

Archives.) 30, The last 1,000

feet to the summit of the Chilkoot Pass. (Public Archives of Canada.) 31, The wagon "road" on the White Pass Trail,

three miles from the summit. (Yukon

Archives.) 32, A portion of the

stampede settlement at Lindeman Lake. (Yukon Archives.) 33, Bennett, 1898. (Yukon Archives.) 34, North-West Mounted Police post at Tagish Lake

where every boat and its occupants were registered. (Yukon Archives.) 35, The tramline between Miles Canyon and

Whitehorse Rapids. (Public Archives of

Canada.) 36, Shooting the

Whitehorse Rapids. (Public Archives of

Canada.) 37, The Klondike armada

on Lake Laberge. (Yukon

Archives.) 38, Stampeders

arriving at Dawson. (Public Archives

of Canada.)

|

The Klondike discovery occasioned a great mass movement to Dawson,

the metropolis of the gold fields. In Dawson the population expanded so

rapidly that the supply organizations were unable to keep pace with

increasing demand. As winter descended upon the Klondike in 1897, the

prospect of starvation loomed ominously. As a result, the government

passed a regulation in January 1898 that no one was to be permitted to

enter Canadian territory without having the means of survival on his

person, or more specifically, as it turned out, on his

back.38

Just how effective this regulation was in terms of forcing the

typical stampeder to pack the legendary ton of supplies over the trail

is open to question. While much has been written about the unreliability

of many of the handbooks that purported to provide the stampeder with

information about his trip, almost all were unanimous in recommending

that the tenderfoot take enough supplies to get him over the trail and

established in the gold fields. Because the regulation requiring the

year's supply of provisions was proclaimed in January 1898 when most of

the stampeders were already on the trail, it seems doubtful that it had

much effect. There is, for example, no record of any bona fide stampeder

being turned back at the summit because he lacked the requisite

supplies. In fact, it appears that the North-West Mounted Police

regarded the regulations as a means of denying entry to "undesirables."

The fact remains, however, that packing was one of the most severe

trials that the stampeder had to suffer in his quest for the

Klondike.

Those who were fortunate enough to have money met the regulation

without difficulty. They hired Indian packers, contracted the task out

to one of the packing outfits that did business along the trail, or

procured pack animals. For those who had mortgaged themselves to the

limit in order to make the trip, however, and they constituted the

majority, the import of the regulation was quite simple — they

would have to transport their supplies on their backs. Few of them knew

at the outset how to maximize space and distribute weight in manageable

allotments. It was only through trial and error and after a great deal

of hardship that the stampeders learned to pack and move their outfits

in stout canvas bags 50 inches long. Arranging the pack so the centre of

gravity rested on the shoulders, with a strap around the forehead to

give extra support, the typical stampeder transported 50 to 60 pounds at

a time. The outfit was moved in relays of about five miles and

cached, the process being repeated until the entire outfit had moved

from the coast to the lakes. The relay system had the effect of

concentrating all the traffic on one part of trail, a fact that resulted

in numerous blockages, loss of time and general deterioration of the

trail. In all, about 30 trips were needed to freight an outfit from one

cache to another and 90 days to move it over the trail from the coast to

the head of navigation at Bennett Lake. It has been estimated that by

the time a stampeder had completed this task he would have walked at

least twenty-five hundred miles.39

The route leading over the White Pass, while less popular than its

rival, the Chilkoot, attracted some five thousand of those who stampeded

to the Klondike in 1897-98. This pass, named by William Ogilvie in

1887 after Sir Thomas White, then minister of the Interior, had been

known for ten years before the gold rush.40 Captain William

Moore, a former steamboat captain, is generally credited with its

discovery. Between 1887 and 1897, Moore and the White Pass, which he

virtually came to regard as his personal possession, waged competition

with their rivals John J. Healy and the Chilkoot Pass in an attempt to

siphon off the traffic going into the interior. Despite Moore's

endeavours, however, the White Pass remained unused until the gold rush

when it was suddenly thrust into prominence.

The White Pass route had two great advantages over the Chilkoot

route: Skagway, at the foot of the White Pass, had a harbour whereas

Dyea did not, and the trail through the White Pass was low enough to use

pack animals over the summit. As a result, pack animals were shipped by

the hundreds to Skagway. Of all the animals that were employed as beasts

of burden, horses and mules proved to be the most adaptable to northern

conditions. Burros were too small and oxen were too slow to traverse the

boggy ground so characteristic of the White Pass route. At first some

attempt was made to make the trail passable for the pack animals and

some stretches of corduroy were laid, but, as one observer pointed out,

"the moment a horse could by any means be got over the trail, all

further improvement ceased and was never again

resumed."41

The great demand for horses on the White Pass Trail during

1897-98 was reflected in the $300-price which horses commanded in

Skagway. A few enterprising men recognized that here was a mine

potentially richer than the gold fields themselves and horses that had

been slated for the glue factory only days before found themselves

relegated to the hell of the Skagway trail. As Robert Kirk noted, even

excellently conditioned horses fell victim to the ignorance of their new

masters, the weather, the bad trail, the poor food and the lack of rest

that awaited them in Skagway.42

By late 1897 the White Pass route on the coastal side of the summit

had become so littered with the carcasses of horses that the stampeders

were referring to it as the Dead Horse Trail. In their insane urge to

reach Dawson as quickly as possible, the stampeders had made no

improvements. The boggy trail had deteriorated under the constant

pounding of feet to the point where it became impassable. As a result,

the trail was temporarily closed and a wagon road was built by George

Brackett to White Pass City, ten miles up the trail from Skagway.

Brackett charged a toll of $20 a ton for the use of his road, but,

unlike the toll that was charged for the use of the stairway of ice on

the summit of the Chilkoot, Brackett encountered one problem after

another in his attempts to collect it.43

The trails leading over the Chilkoot and White passes converged on

Bennett Lake, the former via Lindeman Lake. During the winter of

1897-98, a tent city, well in excess of ten thousand people,

mushroomed at the head of the lake as stampeders stopped to build the

motley armada that would carry them down the Yukon River system after

the spring break-up.44 Although knock down boats constituted

a standard item in most Klondike outfits and many stampeders packed the

necessary construction materials over the passes, the demand for boats

so exceeded the capacity of what few shipbuilders there were that

priority was given to the construction of large freight scows. These

freight scows, built by such contractors as King's Sawmill and Shipyard.

were made of two inch planking, forty-two feet long, and twelve

feet wide, with straight sides. They were square at both ends,

but sheered up like a barge, with pointed outriggers running

about eight feet at the bow and stern, and a long heavy sweep at

the end. They were decked fore and aft for eight feet, with the

middle open, and a plank ran around the sides to walk on.

Each scow had a mast about twenty feet high, rigged with a square

sail. The mast was set about eight feet back of the bow, so that a man

could work the sweep in front of it. Sails were used only when crossing

the lakes. Usually a tent was placed over the cockpit in the middle.

After the cargo was loaded, this was where the crew lived,

cooking on a little sheet iron stove. The scows were unpainted, were

capable of carrying twenty tons, and drew from 24 to 26

inches.45

A similar problem of supply and demand beset sawmill operators who

had established themselves at Bennett to satisfy those who could not

afford the price of a ready-made boat ($300 to $500) or had failed to

include the requisite materials in their outfits.46 A

shortage of labour exacerbated the situation when few stampeders showed

any inclination to work for wages and possibly defer their arrival in

Dawson. The problem was partially alleviated when a compromise was

worked out whereby those who wanted boat lumber supplied the mill with

raw timber and took lumber that had already been cut into boards to

build their vessels.47 For most of those who streamed north,

however, cutting timber for their own use and assembling boats of their

own manufacture was the rule.

After the lumber was whipsawed, a frame was constructed, the sides

and bottom were nailed to the frame and the cracks were caulked and

pitched. Then the oars or poles were cut, a mast erected and seats

nailed down for the last leg of the race for Dawson.48 To

increase the speed of these vessels — some fragile and unseaworthy,

some barely adequate, and only a few built well enough to ensure safe

passage down the watercourse — the stampeders used blanket sails

and "current sails." The current sail was a device consisting of a piece

of canvas weighted with rocks and dropped into the water. The

undercurrent catching this submerged sail countered contrary winds and

augmented downwinds where the water was deep enough so the current sail

did not drag on the bottom.49

Having survived the perils of the trip up the coast, the adversity of

the passes and the misery of the whipsaw pits at Bennett, the stampeder

had yet two more serious obstacles to face — Miles Canyon and the

Whitehorse Rapids. The canyon, a turbulent, dangerous stretch of water

at the foot of which was a series of rapids, was to claim several lives

before the North-West Mounted Police passed a regulation that only

skilled pilots were to take boats through Miles Canyon and the

Whitehorse Rapids.50 Fines of $100 were levied against all

who violated this rule. The regulations also prohibited women and

children from accompanying the pilot through the canyon to the foot of

the rapids although this prohibition was occasionally evaded. The

pilots, who were licensed by the North-West Mounted Police, charged $20

to $25 for each boat they took down. One of the most famous of them was

Jack London, who was later to gain fame as a popular novelist. On a

good day a pilot could make ten trips, returning to the head of the

canyon from the foot of the rapids on horseback.51 One look

at this violent stretch of water, however, persuaded many a stampeder

against trusting the fate of his possessions to the skill of a pilot. As

a result, a windlass was rigged up on the east side of the river in the

spring of 1898 to haul the boats out of the water and a tramway was

built by Norman Macaulay from the head of Miles Canyon to the foot of

the Whitehorse Rapids, a distance of about five miles. The tramway

consisted of peeled logs, eight inches in diameter, over which horses

pulled wagons with cast-iron concave wheels. The freight rate on

Macaulay's tramline, which he named "The Whitehorse Rapids Tramway

Company," was three cents a pound and an additional $25 was charged

for each boat. Shortly thereafter, another tramway, this one six and

one-half miles long, was built on the west bank by a John Hepburn, but

the competition affected both operations and Hepburn sold out to

Macaulay for $60,000.52

Once through the Whitehorse Rapids, the way to Dawson was unimpeded

except for the minor obstructions at Five Fingers and Rink rapids. These

obstacles, however, were not difficult to negotiate with boats of the

size used by the stampeders. By mid-June the flotilla began to stream

into Dawson.53 The ordeal of the past few months meant

nothing. The success or failure of the stampede was now to be

determined in the Klondike gold fields.

IV

The gold rush gave birth to many elaborate transportation schemes for

facilitating the movement of men and supplies into the Yukon. This was a

natural response to the news coming out of the Klondike that gold was

there for the taking. A myth was in the process of being created —

that nuggets of gold covered the Klondike landscape in such profusion

that they only awaited some lucky soul to gather them up. Nor was this

myth challenged by those who had struck it rich in 1896-97 and who

now found themselves deluged by gold seekers eager for information about

the Yukon, "You might just as well believe what you hear," the former

confided, "because you just can't tell lies about Klondike. It's all

true."54 In the popular imagination, therefore, it was

neither the finding nor the mining of the gold that caused people to

hesitate about leaving for the Klondike; the obstacle to be overcome

was that of getting to the gold fields themselves.

It is hardly surprising that two of these transportation schemes

which promised to convey the prospective stampeder to the Yukon without

the exertion required by more conventional forms of transportation were

based on inventions that had captured the popular imagination of the

time: the bicycle55 and the balloon. In Kalamazoo, Michigan,

a man by the name of Frank Corey built an airship to carry him to the

Klondike when news of the phenomenal discovery broke in the American

press. Corey's plan was to take two men on the inaugural flight so each

of them could stake claims and thereafter to run fortnightly flights to

the Yukon. His scheme reached its climax when requests for tickets

started to pour in, but, despite the enthusiasm it had generated,

neither the plan nor the airship ever left the ground. In Seattle,

Washington, meanwhile, the Jacobs Transportation Company invested

$150,000 in another balloon scheme, this one conceived by a Don Carlos

Stevens. It was Stevens's plan to operate regular flights from Tesklo

Bay near Juneau to Dawson and so enthusiastic did he become about the

whole thing that he let it be known that when he got to Tesklo Bay he

would hang out a sign — "All Aboard for Klondike" — "and

when I've got my passengers I'll cut the rope and away we'll go." In

this instance, Tesklo Bay's proximity to Dawson, in comparison to that

of Kalamazoo's, was of little consequence. The promoters, it turned

out, had more hot air than the balloon.56

Other transportation schemes that were talked about but never made it

off the drawing boards were legion. The Pullman Palace Car Company

completed a prototype for an electric sleigh which the Great Northern

Mining and Transportation Company intended to use on the Klondike

creeks. Complete with steam heat, electric lights and elegant interior

appointments, the prototype was designed to travel at the then

breath-taking speed of 60 miles an hour. The degree of disappointment

felt by Yukon plutocrats and would-be plutocrats must have been great

when news was received that the scheme had failed, but unfortunately

their disappointment was never recorded. Another solution to the

northern transportation problem was conceived by the Klondike Combined

Sledge and Boat Company, which designed a steel sledge and barge which

it intended to market in the summer of 1898. This contraption had sails

and oars, air chambers for buoyancy and, as an added inducement,

burglar-proof compartments for gold. Like its predecessor, this scheme

suffered an unheralded end and one can only speculate whether its

failure was the result of impracticality or the end of the gold

rush.57

The experience of a stampeder setting out from Edmonton would tend to

suggest the former. He also built a "sleigh-boat," the overland motive

power for which was to be supplied by a horse until a river was reached,

at which point the device would be capsized to make a boat. The one

problem never resolved by the inventor, however, proved to be the

contraption's failing. "When the snow and ice were on the ground," an

eyewitness remarked incredulously, "the rivers were also frozen."

Edmonton was privy to another scheme which did make some sense. This

device was a steam sleigh which had a cogwheel for traction.

Nevertheless, the progress it made failed to create a favourable

impression — only 18 inches. The steam sleigh only bored itself

deeper and deeper into the ground as a result of the action of the

cogwheel. Other ideas which attracted attention during the gold rush

included carts mounted on buggy wheels and large unicycles around which

platforms had been built.58

Two other schemes to expedite the movement of supplies, particularly

food, had Scandinavian origins. The first was made by a captain of the

Royal Norwegian Army, Nils Muller, who suggested to Clifford Sifton that

a series of stations be built between the coast and Dawson, and manned

by a corps of Norwegian skiers. Muller wrote that

A skiloper with a full load of provisions is able to cover 15

miles per day — with one or two days provisions about 30 or

35. But with a sufficient number for relieving at each station the

distance between Dawson City and Dyea may easily be covered in 8

days — counting 20 working hours per day.59

How this mode of human transport was to adequately supply the

needs of some thirty thousand people was never answered and for its part

the Department of the Interior showed no interest in finding out. In the

meantime, the Alaska missionary, Sheldon Jackson, had persuaded the

United States government to relieve the food crisis by driving a large

herd of reindeer overland from the coast, the reindeer to supply not

only transportation, but ultimately the fare of hungry Dawsonites. Like

its predecessors, this scheme failed when most of the reindeer died of

starvation before reaching their destination.60

Of the many transportation schemes that were stillborn during the

gold rush, none was more interesting nor perhaps more deserving of

attention than the proposal for a monorail. The brain child of a David

Jones from San Francisco, the monorail appeared to be an effective

answer to the northern transportation problem. Its originator claimed

that "it can be carried above the snow and the line can always be

available for service, it can be run over steep grades either by

friction rollers or cog and back gearing and could be built

rapidly."61 Unlike so many others who were out for some fast

money, James did not want to sell his plan; rather he sought employment

in the civil service to develop his scheme. However, the Canadian

government gave short shrift to his proposal and both his idea and his

desire for employment were refused.62

All of these transportation schemes had one thing in common: all

failed to find application for one reason or another. Many of them were

products of the hysteria that was typical of the gold-rush period,

poorly thought out, and perhaps in no way dissimilar to the contraptions

which amateur inventors try to pass off as perpetual motion machines,

but others, if not successful, were forerunners of things to come. In

the invention of the steam sleigh propelled by a cogwheel, for example,

we can see a precursor to the snowmobile, a device well-suited to the

needs of northern transportation. For the immediate future as men

conceived it in 1898, however, the solution to the northern

transportation problem was not to be found in snowmobiles. For that,

men would turn to the 19th-century panacea for all transportation

problems — the railroad.

V

The Klondike gold rush caused a stampede of railroad incorporations

which in its own peculiar fashion was as great as its human counterpart

over the passes. In 1897, 32 railroad companies applied for federal

charters to build lines into the Yukon. In the same year the Province of

British Columbia incorporated 10, while between 1897 and 1899 another 12

filed articles of incorporation in the United States.63 In

1897 the Canadian government commissioned a series of surveys to

determine the most feasible route for a railway and in 1898 it sponsored

its own scheme to build a line between the head of navigation on the

Stikine River and Teslin Lake.64

The one railroad scheme that finally materialized was not wholly

inspired by the gold rush. In 1895 a group of English capitalists who

had formed the British Columbia Development Association sent one of

their number, Charles Herbert Wilkinson, to Canada's westernmost

province to investigate investment prospects. From Ernest Billinghurst,

the brother of another member of the syndicate, Wilkinson learned of

Captain William Moore. Moore, discoverer of the White Pass and its

foremost promoter, had previously sought money from Billinghurst to

develop a route over this pass. Consequently Billinghurst introduced

Moore to Wilkinson. Wilkinson showed enough interest in Moore's scheme

to send Billinghurst to Skagway. Billinghurst reported favourably and in

1896 a decision was made by the syndicate to proceed with a

transportation project of an undetermined nature. A small sum of money

was placed at Moore's disposal and in 1896 Moore used this money to cut

a rough trail a few miles out of Skagway.65 This initial

development work was followed by the incorporation of two Canadian

companies in May and June of 1897, the British Columbia-Yukon Railway

Company and the British Yukon Mining, Trading and Transportation

Company, to build a railroad from the summit of White Pass to the

trading post of Selkirk on the Yukon River.66 The absence of

enabling legislation providing for railroads in Alaska prevented the

syndicate from obtaining a right of way between Skagway and the

summit.67

The incorporation of these two companies predated the beginnings of

the Klondike stampede by some three weeks. Thus the decision to build a

railroad into the Yukon, if not actually proceed with its construction,

was not a result of the gold rush. In fact, considering the short

duration of most gold rushes, the Yukon's remoteness and the cost of

building a railroad over such difficult terrain as the Alaska Panhandle,

the gold rush was not of itself an altogether attractive proposition for

investing in a transportation system as permanent as a railroad. This is

not to suggest, however, that the promoters were unaware of the Bonanza

Creek discovery nor that the discovery had no effect in their application for

the railroad charters. As Tappan Adney has pointed out, the Klondike

discovery was "common property outside six months before" the

Portland and Excelsior caused the "acute attack of

insanity" that precipitated the stampede.68 What should be

noted is that other factors not directly related to the gold rush played

an important role in the syndicate's decision to build the railway.

Information culled from official and unofficial sources suggested that

gold was not the only resource which could be profitably exploited.

Reports concerning grazing land, timber and other metals indicated that

the Yukon had a potentially rich and diversified economic base, a

crucial consideration in light of past gold rushes and the exhaustible

and nonrenewable nature of gold mining.69

When news of the Klondike discovery broke in the English press in

August of 1897, the British Columbia Development Association found

itself in an excellent position to exploit the transportation potential

of the ensuing stampede. The syndicate, however, had fallen on bad times

and a lien was taken on it by the English financial house of Close

Brothers. When the syndicate failed in March 1898, Close Brothers

appropriated its assets, including the two railroad charters that had

been secured the previous spring.70

On 29 March 1898 Close Brothers obtained a West Virginia charter to

build a railroad between Skagway and the summit of White Pass. With the

passage of a bill "Extending the Homestead Laws and Providing for Right

of Way for Railroads in the District of Alaska" by the United States

Congress on 14 May 1898, and the subsequent approval by the secretary of

the Interior of the company's application for a right of way from

Skagway to the summit, the last legislative obstacles to a

Skagway-Selkirk railroad were overcome.71

In the meantime, a representative of Close Brothers, Sir Thomas

Tancred, had travelled to Skagway to determine the feasibility of

building the railroad. With two United States representatives of the

firm, Samuel H. Graves and E.C. Hawkins, in tow, Tancred arrived in

Skagway in April.72

Once in Skagway, Graves and Hawkins made a preliminary survey of

possible routes leading over the White Pass. After a cursory examination

of the area, they met with Tancred in the bar of the St. James Hotel in

Skagway. There they discussed the feasibility of building the railroad

and debated what recommendations Tancred should relay to the investors

on his return to England. On the basis of their survey, Graves and

Hawkins were agreed that the rail line could not be built. At this point

the discussion was on the verge of breaking up and with it the railroad

scheme when something occurred that was to be of major consequence for

the railroad scheme, the subsequent course of transportation history in

the Yukon and indeed the history of the Yukon Territory itself. Michael

J. Heney, an independent railroad contractor, had overheard their

conversation. Heney, who had been lured to the north by the vision of

building a railroad into the Yukon, had conducted an extensive survey of

the area leading out of Skagway and was convinced that a railroad could

be built. The only thing he lacked was capital. With the conviction of a

man obsessed and the persuasiveness of one who knew that his dream hung

in the balance, Heney set out to convince Tancred, Graves and Hawkins

that he was right. His determination and his experience won the Close

Brothers' representatives over. On 27 May 1898, men and supplies were

landed at Skagway. The following day construction

commenced.73

The construction phase was beset by many problems. Skagway was over a

thousand miles from Vancouver, Victoria or Seattle, the nearest supply

bases, and the only connecting transportation service was by water. The

capacity of the coastal steamer fleet that served Skagway and other

points on the Panhandle, moreover, was taxed to the limit by the

stampeders. With the end of the gold rush a momentary respite ensued,

only to disappear with the outbreak of hostilities in Cuba and war with

Spain. The war brought the United States government into direct

competition with the railroad for transportation services on the coast

and the American government forced its advantage by pressing

practically every available vessel on the Pacific coast into government

service. In Alaska the terrain over which the roadbed was to be laid

was devoid of material adequate for ballast and as a result, ballast had

to be hauled from the bed of the Skagway River at one end and from

Fraser at the other. These difficulties were exacerbated by an

insufficient labour supply. "It was obviously out of the question to

engage men in the ordinary way and convey them in hundreds at our cost

to Skagway, the first president of the railroad later recalled, "because

while the gold fever was at its height, the moment they set foot ashore

in Skagway would be our last glimpse of them."74

Nevertheless, the harsh reality of the gold rush partially offset this

problem. There were literally hundreds of vagrants in Skagway awaiting

the arrival of friends, money or both before hitting the trail for the

gold fields. Here was a ready-made labour market if, albeit, an

unskilled one. But these vagrants were also a "captive market" and the

merchants of Skagway who dominated the town council realized that once

the railroad began operating, their captive market would disappear. As

a result, the town council made it known that it expected the railroad

to pay for the privilege of operating out of Skagway and if this failed,

the council threatened to seek an injunction preventing the railroad

from laying track on that section of the roadbed that ran through

town.

39 White Pass and Yukon Route railway.

(Map by S. Epps.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

When the controversy was at its height and while the town council was

engaged in a volatile meeting, the railroad crews worked through the

night. By morning the track was laid. Presented with a fait

accompli, the town council capitulated.75 Despite this

small success, however, the company's labour problems were not fully

overcome. Turnover continued at a rapid rate as men, heretofore forced

to remain in Skagway for a variety of reasons, found these reasons

obviated with the arrival of their friends or money. No longer

restrained, they would drop their tools and leave for the

Klondike.76

Like so many other transportation projects of the period, the White

Pass and Yukon Route77 railway was built with the intention

of returning an immediate profit to its investors. But while other

transportation companies, cognizant of the boom and bust nature of the

gold-rush phenomenon, operated on the "high-grading" principle with

planned obsolescence in mind, the railroad was designed as a permanent

fixture in the Yukon transportation system. It would be built, Samuel

Graves noted,

in the belief that the line that would pay best was

a well located one, with the lowest possible gradients and a very

solid roadbed over which heavy engines could haul heavy loads up the

hill in summertime, and which would admit of modern appliances for snow

fighting in the winter.78

The intentions of those on the site, however, could and often did

exceed the expectations of observers in Skagway and indeed the

expectations of some of the investors themselves. In Skagway local wags

referred to the project derisively as the "Jackass and Yukon Railway,"

while in England some of the less enthusiastic shareholders tried to

jettison the scheme with arguments in favour of a

tramline.79 But the contractors and the Close Brothers

representatives in the field persisted and as the weeks slipped by the

line finally began to take shape.

By 21 July four miles of track had been completed.80 This

brought the roadbed to the foot of the pass where the most difficult

section in terms of construction would begin. Here the White Pass rose

to an altitude of 2,885 feet in 14 miles. In order to reduce the

gradient, 21 miles of track were required. The problems involved in

finding a satisfactory roadbed for the additional 7 miles of track were

complicated by Brackett's wagon road. The right of way that Brackett had

reserved for his road was the most direct and feasible line to the

summit and while the roadbed for the railway could cross this line, it

could not run parallel to it. Finally, after several attempts to skirt

Brackett's road, which were made even more costly by the need to remove

debris that constantly fell on the wagon road as the railroad crews

carved out the roadbed, the White Pass and Yukon Route bought Brackett

out.81 As the railroad slowly inched its way up the pass to

Heney Station during August of 1898, word of the gold strike at Atlin,

British Columbia, reached the construction camps. Its impact was immediate

as an estimated 65 per cent of the work force abandoned their jobs

and stampeded to Atlin. It was not until October that the company was

able to replenish the crew to their pre-Atlin levels and by that time

two valuable summer months of construction time had

elapsed.82

With the onslaught of Alaskan winter, construction entered a new

stage. Winter work required an almost superhuman effort. "The strong

winds and severe cold made the men torpid, and benumbed not merely their

bodies but their minds," Graves wrote, "so that after an hour's work, it

was necessary to relieve them by fresh men."83 At mile 15 the

crews reached the most difficult stretch on the line. Here a

perpendicular wall of granite rose nearly two thousand feet from the

canyon floor. Polished by the action of long-extinct glaciers and worn

sooth by the winds that ripped through the pass, this stretch presented

a problem of the severest order. Working on platforms supported by

crowbars drilled into the granite below and suspended by ropes secured

from above, the labourers blasted and hacked the face of the rock until

a tenuous horizontal ribbon had been cut for the roadbed. A mile further

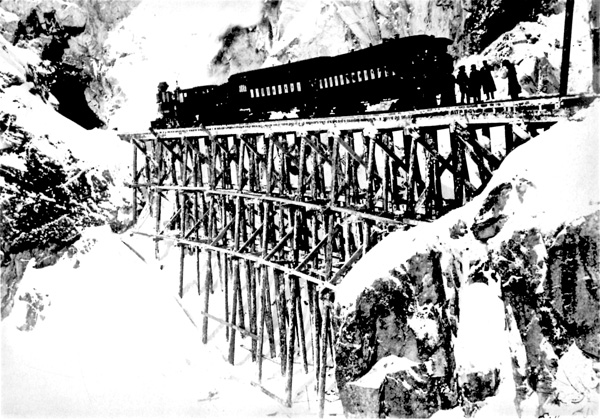

on, a tunnel 250 feet long was bored through the mountain. At mile 19,

the Dead Horse Gulch Viaduct, a switchback 215 feet above a

rock-strewn stream was built. Finally on 18 February 1899 the summit

was reached. Two days later freight and passenger trains were placed in

service.84

Once over the summit, construction proceeded apace to the head of

Bennett Lake. To facilitate supply, Heney organized a teamster operation

which doubled as a passenger- and freight-carrying service between the

summit and the lake. When the railroad reached Bennett on 6 July 1899,

the horses and wagons were withdrawn and made ready for use over the

frozen surface of the lake that winter.85

40 Cutting the grade for the White Pass and Yukon Route railway on

Tunnel Mountain.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

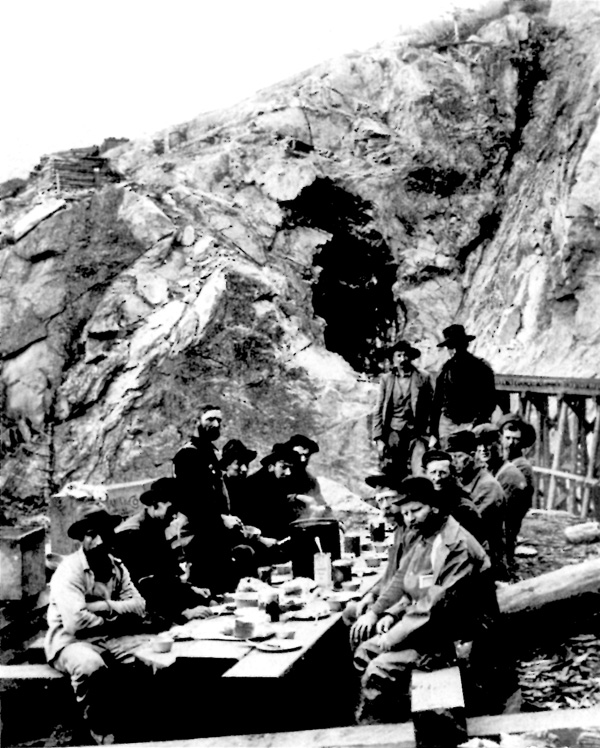

41 A crew pauses for a noon meal at the entrance to the tunnel.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

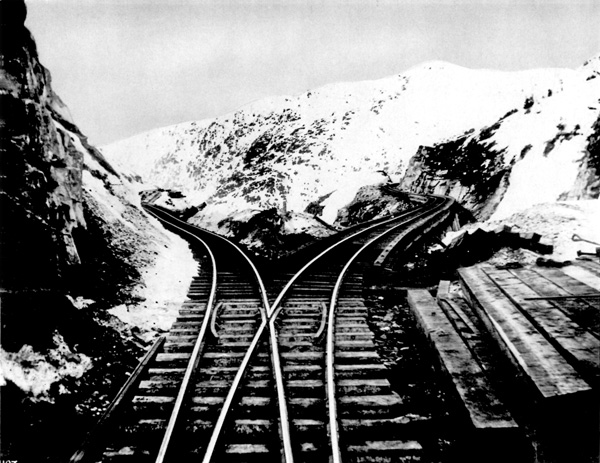

42 The switchback at mile 19.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

43 A railroad crew clears the grade and lays track. Occasionally

the rails dipped and swayed with the configuration of the ground.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

44 Wheelbarrow crews remove rock near the summit of White

Pass.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

45 A cut through glacial frost and what appears to be a

causeway in the distance.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

46 The first passenger train to the summit of White Pass.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

From Bennett the survey called for the line to skirt the eastern

shore of the lake to Caribou Crossing (now Carcross). Because heavy rock

blasting was required on this section, the company transferred most of

its operations to the Caribou Crossing-Whitehorse section with the

exception of the rock crews which were left to cut out the road beside

the lake. The decision to complete the first and last sections of the

railway before tackling the middle made it necessary to move rails,

engines, rolling stock and other material over the middle section to

Caribou Crossing. For this purpose the lake was used as a connecting

link and a power barge was built. As with Heney's horse-drawn wagons

that had operated between the summit and Bennett, the barge was also

used to move people and supplies going on to Dawson.86 When

the lake froze over that fall, the White Pass and Yukon Route organized

the "Red Line Transportation Company." This cartage service moved "a

large number of passengers and hundreds of tons of freight, including

material, engines and boilers etc., for a number of steamers built at

the head of Lake Bennett that spring." On 8 June 1900 the Caribou

Crossing-Whitehorse section was finished. In the meantime the company

had bought out Macaulay's tramlines at Miles Canyon and Whitehorse in

order to secure a right of way. With the completion of the line between

Caribou Crossing and Whitehorse, a through transportation service was

inaugurated between Skagway and Whitehorse, utilising the power barge on

Bennett Lake. Finally, on 29 July 1900 the Bennett-Caribou Crossing

section was completed. The following day through trains between Skagway

and Whitehorse began operating.87

When completed, the White Pass and Yukon Route railroad was 110.7

miles long. Of this, 20.4 miles of track were in Alaska, 32.2 miles in

British Columbia and 58.1 miles in the Yukon Territory. The railway was

of the narrow-gauge (three feet) type, 45-pound rails having been used.

From Skagway to the summit of White Pass, the most difficult stretch in

terms of construction and maintenance, the line ascended 2,885 feet. The

maximum gradient on this section was 3.9 per cent, the average being

2.6 per cent. The highest elevation was not at the summit of the pass,

however, but at Log Cabin, British Columbia, mile 33, where the railroad

reached an altitude of 2,916 feet. The average track curvature on the

Alaskan side ranged from 16 to 20 degrees. The total construction cost

was approximately ten million dollars and an additional 2.5 million

dollars were spent on rolling stock and equipment.88

All told, some thirty-five hundred men were employed at one time or

another while the railroad was being built. Of this number, 35 died from

all causes including illness as well as accident.89 Writing a

few years after the railroad had been in operation, Graves noted that

probably "no other railway in the world was built by such highly

educated men as worked on our First Section." This phenomenon, a

demographic product of the Klondike stampede, was only one of the

remarkable factors associated with the building of the railroad. Another

was the "White Pass spirit" that prevailed during the construction

phase.90 Except for a short strike in March 1899, which was

precipitated by the company's decision to reduce wages and extend the

working day, no other serious labour-management problems were

encountered.91

As the first train ever to ride on the new rails confidently made its

way from Whitehorse to Skagway, pulling the empty cars which had

accumulated in Whitehorse since June of 1900, an Irish crewman remarked,

"Be Jakers — the first thrain into this country was a thrain OUT."92

Whether he realized it at the time or not, this Irishman perceived

both the challenge and the continuing dilemmas that were to confront

the transportation system of the Yukon, and indeed the Yukon itself, for

the next half century.

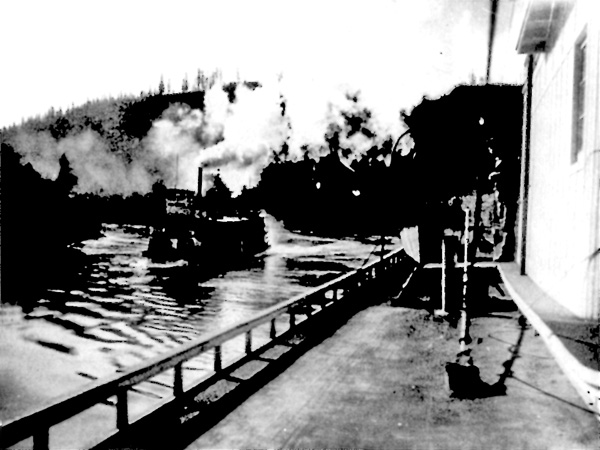

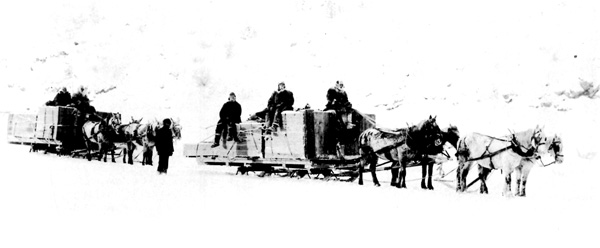

47 The Red Line Transportation Company's last run into

Bennett from the summit, 6 July 1899.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

VI

The pressure of the gold rush on the river transportation system had

an immediate impact that was reflected in the tremendous expansion of

navigation facilities. By August of 1898, 30 additional transportation

companies had joined the original firms, the Alaska Commercial Company

and the North American Transportation and Trading Company, in the

competition for traffic on the Yukon River. Taken together, these

companies operated some 60 sternwheelers, 20 barges and 8

tugboats.93 Despite the unprecedented pressure on the

navigation system, however, the gold rush did not result in the

introduction of any new forms of water transportation. The sternwheeler

retained its role as the basic form of river communication during the

period. While the gold rush was not accompanied by any qualitative

changes in sternwheeler technology, it was marked, nonetheless, by a

significant modification in water routes to the Yukon interior. Before

1898 the sternwheeler had worked the lower Yukon exclusively.

Sternwheeler traffic originating at Saint Michael had never been extended

above Robert Campbell's old fur-trading post at Fort Selkirk. It was

for this reason that Fort Selkirk had been designated the original

terminus of the White Pass and Yukon Route railway.94

The gold-rush popularity of the upper river system was to have a

significant effect on the transport function of the upper and lower

routes. While thousands of people busied themselves in the spring of

1898 building the wind- and pole-propelled vessels that would convey

them from Bennett Lake to Dawson when the ice broke up, a few began the

historic experiment of assembling the steam-powered craft they had

sledded over the passes the previous winter. Though there is some

dispute as to which sternwheeler was the first to successfully navigate

the upper river between Bennett and Dawson that spring,95

that controversy is less important than the success of the experiment

itself. An historic breakthrough had been accomplished — steam had

been introduced on the upper route. The effect of this achievement

was to be of profound consequence for the future of the Yukon

transportation system.

Having demonstrated that the sternwheeler could be successfully used

on the upper river route, a number of sternwheelers were built at

Bennett Lake. Because of the obstacles to through navigation posed by

Miles Canyon and the Whitehorse Rapids, the fleet was separated into two

divisions — one serving the Bennett-Miles Canyon section, and the

other the Whitehorse-Dawson run.96 In 1898 the Bennett Lake

and Klondike Navigation Company operated the Flora and

Nora below Whitehorse to connect with the Dra which plied

between Bennett and Miles Canyon. These vessels were approximately 75

feet long. The trip between Bennett and Dawson took four and one-half

days. Sleeping accommodation consisted of wooden bunks ranged in tiers

of three and the passengers supplied their own bedding. The cost for the

through trip was $75. Meals were an additional dollar each. In the

meantime, the Canadian Development Company had placed the Willie

Irving, the Goddard and the Anglian between Whitehorse

and Dawson. In the summer of 1898 steam service was expanded to include

Lindeman Lake with the operation of a steam ferry to connect with

Bennett.97 The upper route proved to be so successful that it

was able to challenge the historic pattern of river transportation

dominated by the lower river via Saint Michael. As a result, various

sternwheelers like the Victoria were withdrawn from the lower run

and transferred to the upper Yukon.98

With the introduction of sternwheelers on the upper river, the

desirability of extending the railroad to Fort Selkirk, a need which had

previously existed, was obviated. Whitehorse, situated at the foot of

the major impasse to through navigation on the upper river, Miles

Canyon and the rapids, was selected as the terminus for the railroad.

When the railway was finally completed in July of 1900, the upper river

route, served by the railroad and a complementary fleet of

sternwheelers, was in a position to supplant the lower route as the main

life line to Dawson.

VII

Recalling his trip to the Klondike, Robert Kirk wrote that "the

present advanced state of development of the northern mines is due

largely to... dog-teams."99 While Kirk may well have

exaggerated the importance of dogs as a transportation factor in the Yukon

to the detriment of other forms of transportation, it must be admitted

that the dog and the dog team played a crucial role in northern life

during this period.

No one knows when dogs were first used to fulfill a transportation

need in the Yukon. The Indians used them to the extent that their

technologically primitive society demanded and the

Hudson's Bay Company had utilized dogs in the prosecution of the fur

trade. With the coming of the prospector in the 1880s, the use of dogs

had declined in proportion to the falling off of the trade in furs. This

occurred in part because the mines were worked during the summer months

only. Many of the miners left for the outside before the annual fall

freeze-up, while the rest passed the winter months inside their cabins.

The evolution in mining technology occasioned by the introduction of

winter digging in the early 1890s and the discovery of the rich gold

fields in the Klondike in 1896 renewed the demand for dogs and dog

teams.

Dogs were used for a variety of purposes during the Klondike period:

to haul poles, logs and lumber for sluice boxes, drift burning and

cabins; to deliver mail; to reach the small outlying settlements in the

territory; to commute from creek communities to Dawson; to freight

supplies, food and equipment; to carry gold from the mines to Dawson; to

labour in the mines themselves, and to deliver water door to door before

Dawson acquired its water system. During the summer dogs were used as

pack animals; during the winter to draw sleds.100

It has been estimated that by 1899 there were some four thousand

dogs regularly employed in the town of Dawson. While most of these dogs

were privately owned, many of the transportation companies used dogs as

well. Men often made $100 a day freighting supplies to the mines and in

the spring of 1898 a return of $150 a day was not uncommon. During the

summer months gold was brought into Dawson from the mines by dog trains

consisting of 15 to 20 dogs. Each dog in the train carried a pack which

weighed between 20 and 30 pounds. An indication of the wealth conveyed

in this manner is apparent from the fact that a train of 15 dogs, each

dog carrying a 30-pound pack, transported gold to the value of $122,400

(gold valued at $17 an ounce). For two and one-half months during the

summer, the dog trains operated 24 hours a day, six days a week. During

the winter, dog punchers worked eight hours a day, averaging 20 miles

with a load of twelve hundred pounds. Occasionally, the dog teams were

relieved from freighting supplies to the creeks and used for trips to

the coast on Lynn Canal, 500 miles away. During these trips the packers

carried private mail and light express. The charge for carrying a letter

was one dollar, and the driver often increased his revenue by taking a

miner from Dawson to the coast. The passenger generally paid some $500

for the privilege of accompanying the sled, not for riding in it, and

he was expected to assist in the making of camp and the cutting of

firewood and to furnish his own blankets and robe.101

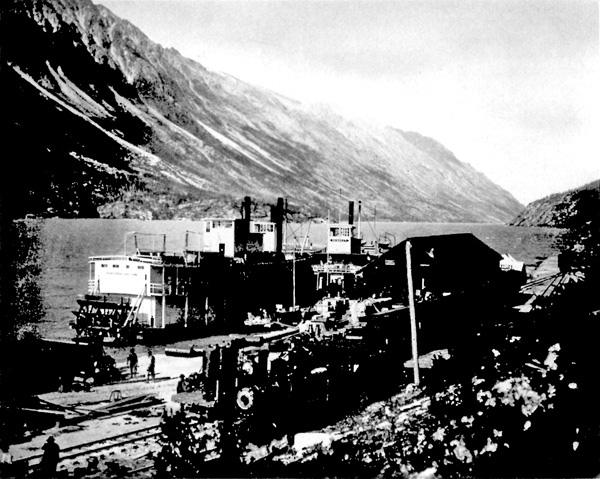

48 The Clifford Sifton, the Bailey and an

unidentified sternwheeler at Bennett. Until the railway

was completed to Whitehorse, Bennett was the head of

navigation on the upper Yukon.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

49 A steamboat race. The vessel on the right is probably the

Canadian since it and the Bailey were involved

in one of the most famous, and wisely one of the few, steamboat

races on the Yukon. According to a report in the Victoria

Daily Colonist of 29 September 1900, "the fight was a

draw. A battle royal had been fought (the Bailey rammed

its opponent twice). The Canadian, although having

somewhat the best of the struggle, was so badly damaged that

no victory was claimed."

(Yukon Archives.)

|

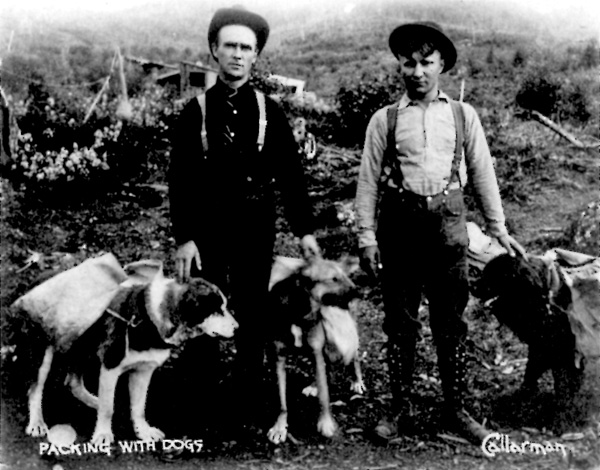

50-56 Dogs performed just about every transport function

conceivable. They packed in summer, made long-distance trips

in winter, provided Dawson and Whitehorse with primitive

"municipal waterworks," and drew loads which belied their

small size.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

Various breeds of dog were used for freighting in the Yukon. By far

the most sought-after were the native breeds; the husky, the malemute

and the "Siwash" or Indian dog. These dogs were aptly suited to the

rigours of the northern environment, being "well-boned, deep chested,

and strong in the back, fore and hind quarters," as well as having thick

outer and inner coats of hair and paws that were well-furred between the

pads and the toes. Arthur Treadwell Walden, a noted Yukon dog puncher,

preferred the husky to the malemute because it was larger and stronger,

and observed that the "Siwash" or Indian dog was generally less

preferable than either because of its supposed indolence. It is

interesting to note that Walden's ascription of greater size and strength

to the husky instead of the malemute reversed the conventional

distinction drawn by professional breeders between the two types of

dogs, thereby suggesting that Walden mistook one for the other. In

addition to their superior physical characteristics, the native dogs

showed a marked propensity for scavenging, to which the elevated food

caches that dotted the northern landscape bore mute testimony. Accounts

of their bad temper were legion as they were quick to attack one another

when confused or frightened and no gold-rush story was considered

complete with out a graphic description of a particularly vicious dog

fight.102

During the gold rush a brisk business was done importing outside

dogs for sale. In fact, contemporary photographs give every indication

that the number of outside dogs far exceeded the number of native breeds

in use at the time. Though not as valuable as the native breeds, these

dogs proved adaptable to northern conditions, nature furnishing them

with a thick coat of hair once the cold weather had set in. They had

neither the strength nor the endurance of the native dogs and their

dietary requirements were also greater, but they were particularly

well-suited to short-distance hauling. Tappan Adney, an acute

observer, noted that for this purpose the St. Bernard and the mastiff

were unsurpassed.103

On the trail, dogs were fed dried salmon, each dog being given

approximately two pounds of fish each day. Not only was dried salmon

relatively cheap, but experience showed that it was also more nourishing