|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 19

Yukon Transportation: A History

by Gordon Bennett

Recession and Recovery

I

Midsummer 1899:

In Dawson, log cabins could be had for the taking as steamboat

after steamboat, jammed from steerage to upper deck, puffed out of town

en route to Nome. The saloon trade fell off; real estate dropped; dance

halls lost their custom. Arizona Charlie Meadows announced that he would

float his Palace Grand in one piece down the river to the new strike.

Jacqueline, the dance-hall girl, complained that her week's percentage

would hardly pay her laundry bill. In a single week in August eight

thousand people left Dawson forever....

And so just three years, almost to the day, after Robert Henderson

encountered George Carmack here on the swampland at the Klondike's

mouth, the great stampede ended as quickly as it had

begun.1

The facile conclusion has long been drawn that the end of the great

stampede marked the end of the Yukon Territory. A popular conception

persists that shortly after 1900 the Yukon somehow disappeared, like

some North American Atlantis, only to reappear in the 1940s and 1950s

when attention was turned to the construction of the Alaska Highway and

man's insatiable appetite for natural resources once more kindled his

interest in the North. In the interim, it is generally believed, nothing

happened.2

Except for a handful of personal reminiscences which make no pretence

of completeness3 and a number of studies pertaining to the

Alaska Highway, this view has been reinforced by a paucity of written

history for the post-gold-rush period. All but ignored interritorial

historiography is that a number of significant themes and events shaped

the course of Yukon development after 1900.

II

In the immediate post-gold-rush period the Yukon Territory entered an

era of protracted economic decline that was to last, with only brief

interruptions, until the 1950s. Although several factors contributed to

this reversal in the territory's fortunes, it was the inherent

instability of the gold-rush economy, not the exhaustion of the gold

fields, which precipitated the decline. Interestingly enough, of the

250-odd million dollars that the gold fields ultimately produced, more

than 75 per cent was taken out after 1900. What distinguished the gold

rush from the post-gold-rush period was not the existence of gold, but

the mode of mining peculiar to each. The tenfold increase in gold

production that attended the gold rush was the product of a massive

input of labour supplied by the Klondike stampede.4 This

increase in the labour market added a new dimension to the economy

— "sheer numbers of people demanding the amenities they had enjoyed

in the south." As a result, a variety of service-oriented enterprises

encompassing medicine and the law, business, commerce, newspapers and

entertainment evolved.5

The pressures toward inflation, already loosed by the free-spending

hysteria that overcame the gold camp, were given a powerful artificial

stimulus by the regulation promulgated by the territory's first

commissioner, James Walsh, that "no person was to come into the city

[Dawson] who had not at least $750 in money or money's worth." Placing

the population of Dawson at thirty thousand in 1898 and taking $1,000 as

the average sum brought into Dawson by each individual, one official

estimated that this "set free within a very small area the enormous sum

of $30,000,000." This in itself was enough to propel an economic boom.

At the same time, the mining industry and the demands of the local

population gave a strong impetus to other industries based on lumbering

and coal mining.6

Yet for all of these stimuli, the foundation upon which the gold-rush

economy rested was fragile. As the rich, easily accessible gold deposits

were exhausted, production declined and the population, no longer having

the means to support itself, decreased. By 1902 the gold-rush economy,

sustained in large part by rising gold production and a rapidly

expanding gold population, had collapsed.7

As early as 1899 there were symptoms of the impending decline when

many abandoned Dawson for the new gold fields in Nome,

Alaska,8 but the severity of the decline was not clearly

apparent until the early 1900s. By then most of the trading and

transportation companies that had sprung up during 1898-99 had

disappeared and by 1904 real estate values had plummeted to less than

one-third their 1899 valuations. By 1904 considerable property was

vacant on Front Street in Dawson and in the words of one observer,

"undoubtedly. . . permanently vacant." Its depreciation, he added, "is

so great as to leave it practically valueless except as to the material

contained in the buildings." That summer "many substantial men . . . and

many more of those who have constituted our floating population" left

Dawson for Fairbanks, Alaska, and another chance at fortune. But the

paradoxical legacy of the gold rush was not that people left the

Klondike after 1899, but that many people remained. Those who did leave

were in the majority, but their departure was predictable. They included

those stampeders whose single motivation was, as J.R. Lotz has noted, to

"clean up and clear out" and the old-timers who had gone to the Yukon

long before news of the Klondike discovery reached the outside. Even as

one government official was confidently noting the evolution of Dawson

"from an uncertain, unstable and excited mining camp to a steady,

permanent and prosperous community," the old-timers "began to get an

uneasy sensation in their spines. It was as if the whole cycle of their

experience was being repeated."9 These men had spent their

entire lives living on the fringes of civilization, only to move on as

civilization progressively encroached upon what they considered to be

the last outposts of their freedom and independence. And now

civilization had overcome Dawson. Like those who had been moved by the

maxim "clean up and clear out," the old-timers recognized that their

time to leave had come.

But the end of the gold rush neither presaged the end of mining in

the Yukon nor did Dawson follow the classic pattern of other

19th-century placer gold-rush centres and become a ghost town. It is

more accurate to regard the post-gold-rush period in the Yukon as

rather one of severe dislocation and readjustment to new circumstances

than demise. The superstructure of the gold-rush economy had been both

superficial and unstable and it disappeared. What followed was a

rationalization and a consolidation of the Yukon's economic base. The

period 1900-14 was not only one of profound economic change

precipitated by a decline in production, it was Dawson's golden age as

well. During that time anarchy gave way to order, ostentation gave way

to studied elegance, and gambling houses, drinking parlours and

prostitutes were gradually replaced by fraternal organizations, churches

and schoolmarms. As was to be expected, the mining industry pointed the

way. After 1901 the labour-intensive, "poor man's" methods of mining

characterized by the pan, the rocker, the sluice, wood burning and the

individual claim were superseded by capital-intensive techniques based

on the dredge, hydraulic monitors, steam thawing and concessions. This

conversion from primitive extractive methods to highly sophisticated

extractive techniques based on machinery gave the area a stability and a

security it had never known before.

The impact of these changes on the transportation industry was not so

great as might be initially supposed. So long as gold mining over an

extensive area continued and so long as a population large enough to

support and be supported by the mining industry remained, transportation

was a basic need. This need did not end in August 1900 when the

residents of Dawson memorialized the governor general for better

transportation facilities; rather it was only the

beginning.10 This is not to suggest, however, that the

aftereffects of the gold rush bypassed the transportation industry. As

was noted above, most of the transportation companies that had sprung up

to serve the needs of the gold-rush population during 1898-99 had

abandoned the field by 1901. Nevertheless,

the quality of transportation in the Yukon did not deteriorate after

1901. If anything, it improved as attempts were made to reduce the

cost-price squeeze and open up new areas for economic exploitation in

the territory.

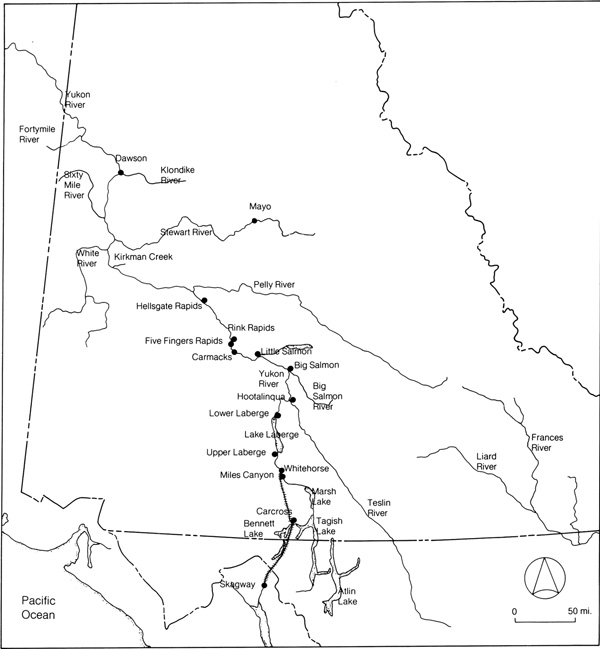

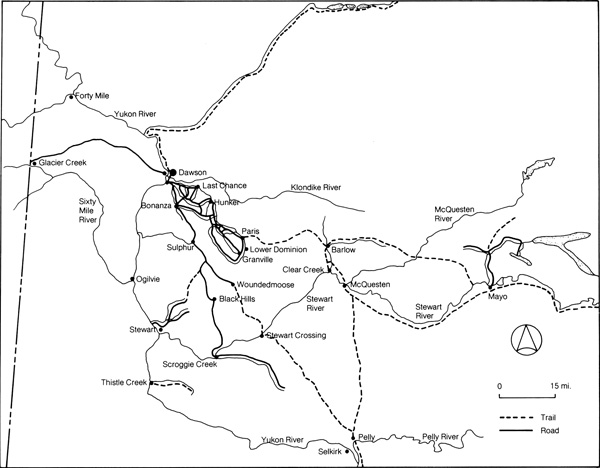

62 Yukon River.

(Map by S. Epps.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

III

The Yukon River continued to be the most important transportation

artery in the Yukon between 1900 and 1914 just as it had been through

the fur trade, early prospecting and gold-rush phases of Yukon history.

The one significant modification that occurred during this period was

the completion of the White Pass and Yukon Route railway from Skagway to

Whitehorse in July of 1900. With the completion of the railway, a

practical alternative to the lower river route via Saint Michael came

into existence. But the emergence of this alternative did not diminish

the river's role; instead, it enhanced it and gave the river a greater

utility. The river itself remained the heart of the Yukon transportation

system. For this reason, an understanding of its peculiar qualities is a

necessary prerequisite to any examination of the evolution of

transportation in the territory.

The Yukon River, 1,993 miles in length, is the fifth-largest river in

North America.11 Authorities differ as to its exact source,

some designating it as Lindeman Lake, others citing the Nisutlin River

and Summit Lake.12 From its source, the Yukon River follows a

tortuous course to its mouth on the Bering Sea off Norton Sound in

Alaska. For half of its length the river flows in a northwesterly

direction through the central plateau of the Yukon Territory. At the

edge of the Arctic Circle it shifts abruptly to the southwest as if

deflected by the inrushing waters of the Porcupine, and from there it

flows on inexorably to the sea. The peculiar ambulations of the

watercourse — here like a corkscrew, there like the furrows in a

field — are suggestive of the contradictions which characterize

the river itself. Inordinately circuitous and difficult to navigate, the

river nonetheless provides an inland waterway through the heart of

Alaska and the Yukon, the only fissure in an otherwise impregnable land

mass. Long by any standard of measurement, the river is shallow through

most of its extent, the consequence of a semiarid climate. Swift on the

upper section, the river rapidly loses velocity as it spills onto the

Yukon plateau, and from there meanders lazily to the sea.13

Unlike any other river of comparable economic importance, certain

sections of the river on the Canadian side of the international

boundary line have different high-water periods during the year. The

section of the river between Marsh Lake and Fort Selkirk, formerly known

as the Lewes, and the section below White River reach their high-water

marks in July and August, after the solar energy of the summer months

has melted the glacial ice that feeds them. On the other hand, those

sections below the river's snow-fed tributaries, the Teslin, Pelly and

Stewart rivers, have their high-water periods in late spring, after the

annual spring break-up of the ice.14

The railway eliminated the obstacles to navigation at Miles Canyon

and Whitehorse, thereby furnishing the necessary conditions for a

successful challenge by the upper route for sternwheeler traffic on the

Yukon River.15 After 1900 the upper river virtually

superseded the lower river as the primary gateway to the interior and by

1915 its traffic monopoly was practically complete. Despite this

weighting of the balance at the expense of the Saint Michael route,

however, serious impediments to navigation on the upper river between

Whitehorse and Dawson existed. On Lake Laberge, the opening of the

navigation season was delayed each spring while sternwheeler crews

anxiously waited for the ice on the lake to rot and break up, some two

weeks after the ice on the river below the lake had gone

out.16 It was not until the early 1920s that this problem

was overcome and the navigation season prolonged by the successful

damming of the headwaters on the lake. At Five Finger Rapids,

approximately 150 miles below Laberge, four massive knuckles of rock

jutted out the water, ready to smash the sternwheeler whose unwary pilot

had failed to hug the east bank. Below the Five Fingers were the sunken

reefs of the Rink Rapids. At Hellsgate Rapids, just above Fort Selkirk,

the island-studded river appeared to flow in greater volume along the

east bank, but the pilot who failed to use the navigation channel near

the west bank did so at his peril.17 Below Kirkman Creek, a

small tributary that was located above the confluence of the White and

Yukon rivers, deposits of detritus caused the navigation channel to

shift throughout the season. These were the major obstacles to

transportation, apart from the climate, on the upper river and this was

the highway that was to be internal life line of the Yukon Territory

until 1950.

Ownership of the railway placed the White Pass and Yukon Route in an

excellent position to exploit the transportation potential of the

upper river route to Dawson. This potential was recognized as early as

1899 by the directors of the company who had had either the perspicacity

or the good fortune to charter the company as a general transportation

line which included the right to build wharfage and docking

facilities.18 With the collapse of the gold-rush economy and

the resultant withdrawal of most of the transportation companies that

had evolved to meet the demands of the gold-rush population, the way was

cleared for the White Pass and Yukon Route to enter the river

transportation business.

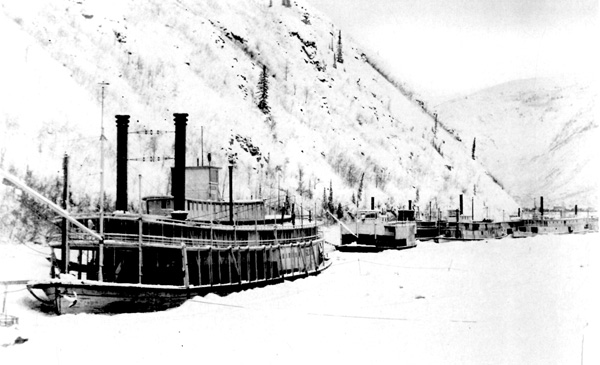

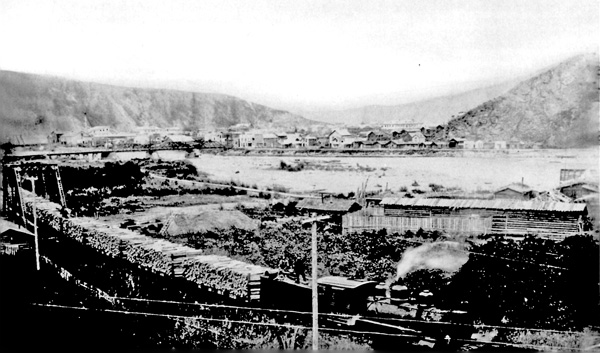

63 Steamers in winter quarters at Dawson. They

were wintered in a slough just above the confluence of the Klondike and

Yukon rivers.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

The decision to set up a river division within the company was

precipitated by the general chaos which prevailed on the river during

1900. As the sole transportation company providing service from

tidewater at Skagway to the head of navigation on the Yukon River at

Whitehorse, all traffic going into and out of the Yukon via the upper

route went by the White Pass and Yukon Route railway. This led to

innumerable problems at the transfer point at Whitehorse where

through shipments of goods were split up, Customs papers lost,

goods stolen on the boats . . . . Many of the boat owners were

not responsible financially, so that the passengers with through

tickets and the goods owners with through bills of lading naturally

preferred to make their claims against us [the White Pass and Yukon

Route], leaving us in our turn to recover from delinquent boat

owners — if we could.19

These difficulties convinced the first president of the company,

S.H. Graves, that in "self-defense we must organize our own river

service."20

The company's plight was not nearly so severe as Graves's statement

would tend to imply. To be sure transhipment mix-ups gave cause for

concern. But the company was also aware that the setting up of a river

division would result in the elimination of any serious competition by

virtue of the company's ownership of the railway. With Tancred's

approval, a river division was subsequently organized and styled the

British Yukon Navigation Company.21 During the winter of

1900-01 the company built a shipyard in Whitehorse and a repair

yard in Dawson.22 Three boats were purchased from the

Canadian Pacific Railway Company, the machinery and fittings from which

were installed in new boats built at the British Yukon Navigation

Company's Whitehorse shipyard.23 On 1 May 1901 the British

Yukon Navigation Company acquired the fleet of its largest potential

competitor, the Canadian Development Company, and shortly thereafter

extended its operations to Atlin, British Columbia.24

The economic vicissitudes of the post-gold-rush period had a serious

impact on the numerous transportation companies plying the Yukon River.

After 1901 most of them withdrew from the field, unable to compete with

the White Pass and Yukon Route's complementary railway and sternwheeler

service. A number managed to sell their boats to the British Yukon

Navigation Company and by 1903 all but three boats on the upper river

were owned by the White Pass subsidiary.25 But though the

post-1900 economy had serious implications for the transportation

companies that had sprung up to serve the demands of the gold rush, it

was of minor consequence for the Yukon transportation system as a whole

and was not without its benefits. The British Yukon Navigation

Company enjoyed a period of relative prosperity between 1901 and 1914

although this prosperity occurred at the expense of competitive

conditions on the upper river. When the conversion to capital-intensive

mining took place after 1903, the transportation legacy of the gold

rush, in the name of the White Pass and Yukon Route, played a vital

role. Without the complementary facilities of the railway and the

post-gold-rush sternwheeler fleet offering through rates from tidewater

to Dawson, the transition to capital-intensive mining would likely have

occurred on a much reduced scale.

By 1907, having pursued an aggressive policy of eliminating common

carrier competition, the British Yukon Navigation Company enjoyed a

monopoly on the upper river limited only by a single independent

company operating one sternwheeler between Whitehorse and Dawson. In the

same year, wharfage rents in Dawson were brought into line with

prevailing conditions by reducing them 50 per cent.26

While transportation on the upper river was adapting itself to the

changing transportation requirements of the territory and exhibiting a

visible trend toward monopoly, a similar process of adaptation was

occurring on the river below Dawson. Before 1901 the lower river had

been the principal supply route to the Klondike gold fields. After the

completion of the railway, however, Skagway replaced Saint Michael as

the main port of entry to the Yukon. The impact of the railway coupled

with the collapse of the gold-rush boom were such that no

transportation company on the lower river showed a profit for its

operations during the 1901 navigation season.27

To strengthen the competitive position of the Saint Michael route and

to offset the depression that hit the transportation industry on the

lower river after 1900, the Alaska Commercial Company, theretofore the

largest trading and transportation company in the Yukon and Alaska,

merged with the International Marine Company and Alaska Goldfields in

1901. The new firm's merchandizing and transportation operations were

then separated into two distinct companies, the Northern Commercial

Company and the Northern Navigation Company. Shortly thereafter the

Northern Navigation Company bought out the Seattle-Yukon Transportation

Company. In 1906 the North American Transportation and Trading Company,

the second-oldest company in the Yukon, sold its sternwheelers and Saint

Michael terminal to the Merchants-Yukon Transportation

Company.28

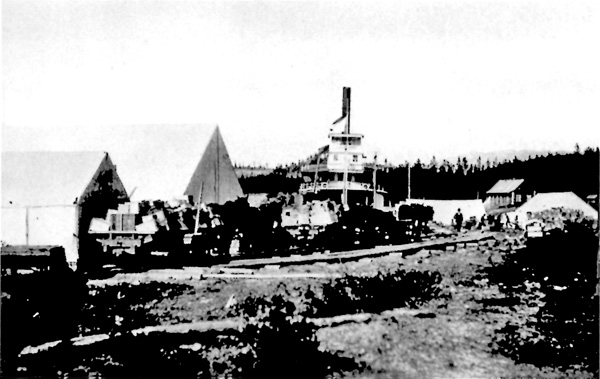

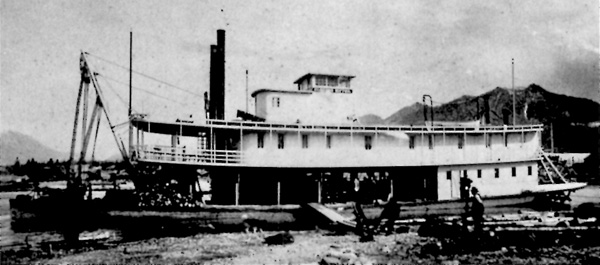

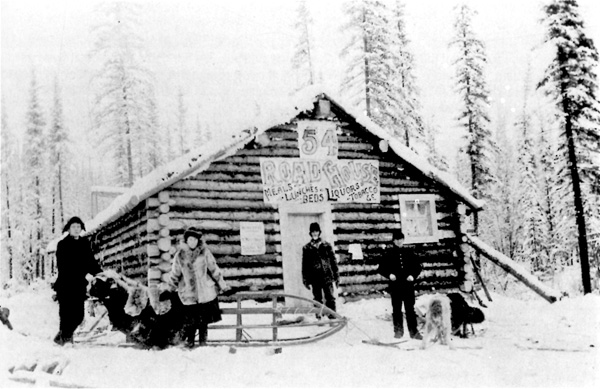

64-66 The evolution of Whitehorse's waterfront, 1899 to 1901.

The shipyard is on the right in Figure 66.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

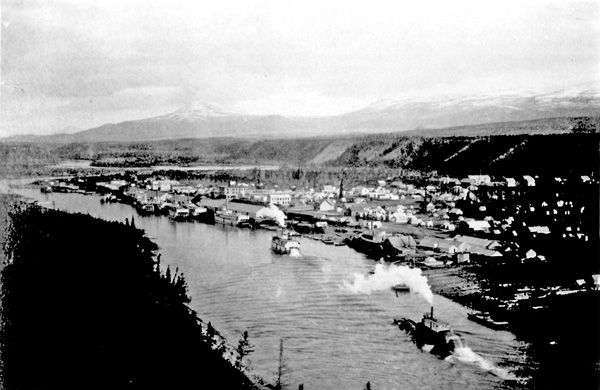

67 The Alaska Commercial Company (later Northern Navigation

Company) steamers Sarah and Susie tied up at

Saint Michael.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

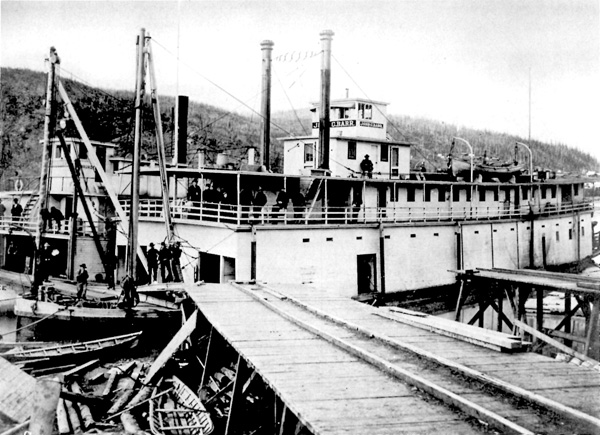

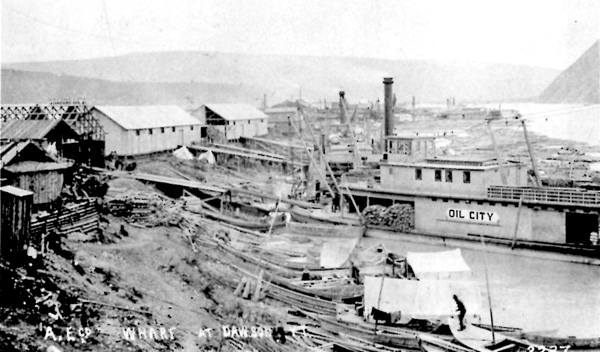

68-70 Typical lower river steamers. Not only size distinguished

the gold-rush boats on the lower river from those of the upper

Yukon. Twin stacks were fairly common on the former, absent on

the latter. The pilot house was usually located further aft on

the lower river boats and on some of the larger ones the

gangway, or swinging stage, was carried toward suspended from a

boom rather than on the for'deck as on most upper river vessels.

Portions of the main deck were often open on the former, almost

always completely enclosed on the latter. Lower river vessels

were more ornamental and resembled sternwheelers typical of

the American Midwest, whereas the boats on the upper river were

similar to river boats of British Columbia, Oregon, and

Washington state.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

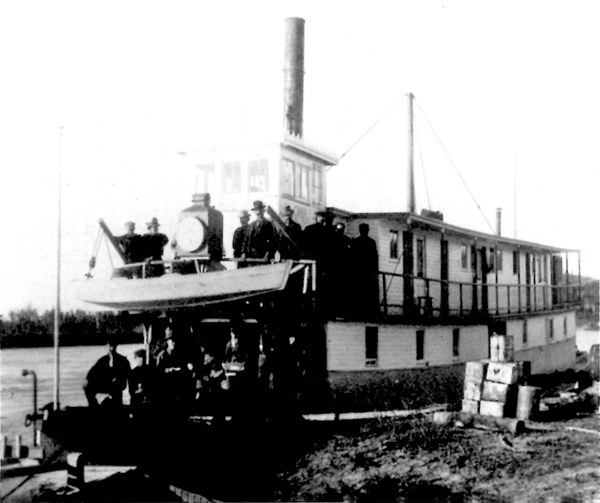

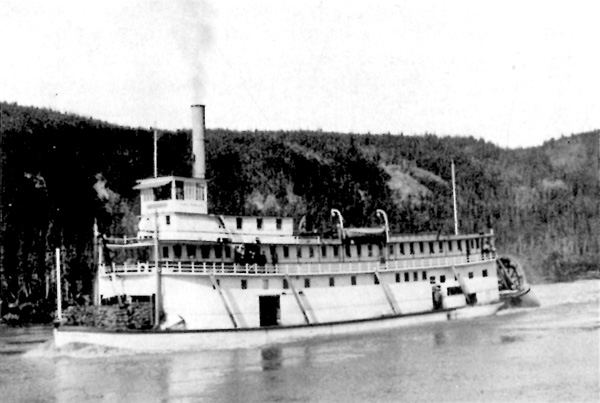

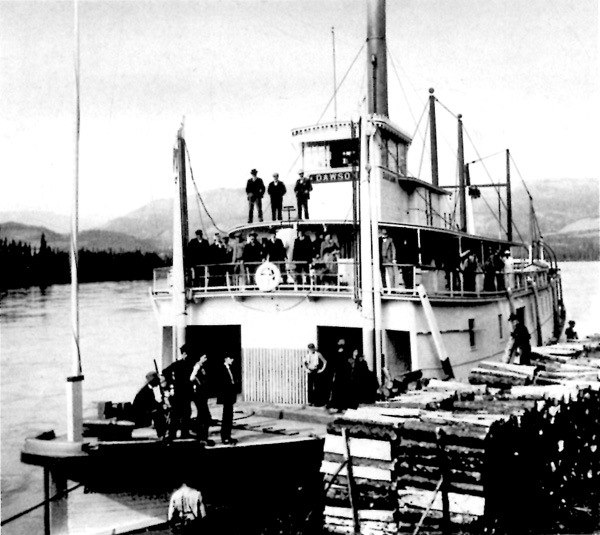

71-74 Typical upper river boats. The Flora (Fig. 71)

was built at Bennett in 1898 for the Bennett Lake and

Klondike Navigation Company by Bert Fowler, who later became

shipyard foreman for the British Yukon Navigation Company.

The Columbian (Fig. 72) was built at Victoria in 1898

by John Todd, who built a number of vessels for the Yukon

River. The Dawson and Selkirk were built by

the British Yukon Navigation Company in 1901 at Whitehorse.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

The elimination of competition through merger prolonged the life of

the Saint Michael route. As well, the lower river possessed certain

competitive advantages which, if not sufficient to turn the tide of

Yukon trade away from the upper route, at least deferred

the lower river's demise. To begin with, larger boats could be used

on the lower river. Second, in supplying Fairbanks, lower-river

companies effectively cut the length of their supply lines to Dawson by

half. Third, some of the largest stores in Dawson were owned by

transportation companies on the lower river whereas the White Pass and

Yukon Route had no merchandizing outlets.29 Finally, the

"exorbitant" freight rates charged by the White Pass and Yukon Route

alienated many Dawson merchants. As one of them declaimed, "look into

Lower R[iver] shipping, the less we ship White Pass, the better for

us."30 But the repeal in 1904 of the law that had previously

permitted the free shipment of Canadian goods from a Canadian port to

Dawson via Saint Michael came as a serious blow to the transportation

companies on the lower river.31

By 1912 business in the Yukon had contracted sufficiently to

precipitate an open fight between the upper and lower river for the

right to supply Dawson. The contestants were, appropriately enough, the

Northern Navigation Company and the British Yukon Navigation Company.

Much to the delight of the residents of Dawson, the first round in the

contest was a rate war. The British Yukon Navigation Company then

carried the fight into Alaska by putting two of their vessels, the

Alaska and the Yukon, on the lower river to connect with

Fairbanks. The Northern Navigation Company retaliated "by contracting

on a continuous basis with heavy shippers for freight to be shipped via

St. Michael." The prospect of mutual bankruptcy finally drove both

companies to the bargaining table and on 10 April 1914 it was announced

that the White Pass and Yukon Route, acting for its wholly owned

subsidiary, the British Yukon Navigation Company, had purchased the

entire river operation of the Northern Navigation Company.32

By 1914 the upper route had established hegemony on the Yukon River.

Although water transportation was primarily confined to the Yukon

River during this period, there was some activity on the tributary

streams. One of the more interesting features of this activity was the

role played by government in diverting attention from the main

watercourse to the tributaries through a policy of direct involvement

in river navigation. Behind this policy was an attempt to diversify and

decentralize the economy of the territory by opening up new areas for

exploitation. In 1906 the Canadian government assisted prospectors going

into the Pelly region by giving them free passage on Royal North-West

Mounted Police steamers. This policy was expanded in 1907 when the

commissioner of the territory announced that the government was

prepared to subsidize transportation companies making trips up the Pelly

and Stewart rivers. Although the subsidies were discontinued after 1908,

they achieved the desired effect and by 1909 light-draft steamers

were operating on the Stewart, Pelly and Hootalinqua rivers. In 1909 as

well, the Side Streams Navigation Company was formed. This company

operated a small sternwheeler that supplied the White, Stewart and Pelly

rivers and the Fortymile River up to the canyon.33 While the

opening up to navigation of the tributaries of the Yukon River did not

result in the discovery of any new large mineral deposits, the side

streams trade was an important addition to the meagre transportation

facilities that had previously served the small communities on these

tributaries.

The sternwheeler underwent certain modifications in design and

engineering following the establishment of the British Yukon Navigation

Company. In large measure this was because the physical characteristics

of the upper river required boats of shallower draft and narrower beam

than those that operated below Dawson. This requirement was not unique

to the Yukon River; it obtained on virtually every major waterway in

Canada and in the United States as steamboat service was extended

upriver. Nor was it as dramatic as the change that had occurred on the

Mississippi where the sternwheeler replaced the sidewheeler as traffic

moved upstream. Outside of one reference which has never been verified,

there is no record of sidewheelers having ever operated on the Yukon.

Thus the evolution that took place on the Yukon was one of degree, not

kind. The development of the Yukon steamboat paralleled the development

of boats on rivers west of and tributary to the Mississippi —

rivers that were narrower and shallower than the Mississippi. Considered

as a prototype, the sternwheeler was more suitable to these smaller

waterways since its rear-mounted paddlewheel and relatively

flat-bottomed hull were conducive to operating in shallow water and the

absence of sidewheels gave it a narrower beam than the lower Mississippi

steamer and hence the ability to negotiate narrower channels. The

stern-mounted wheel provided other advantages as well: it gave grounded

steamers an opportunity to wash away sand from the hull by reversing

engines; it was protected by the hull from snags and sweepers, and

because it was designed for low water, it permitted the sternwheeler to

land virtually anywhere along a riverbank without special docking

facilities.

The sternwheelers that were built by the British Yukon Navigation

Company were patterned after the "swift water" boats that operated on

the Snake, Willamette and Upper Columbia rivers, rivers that more

closely approximated travelling conditions on the upper

Yukon.34 They were designed to carry heavy cargoes downstream

on a very light draft and to make the return trip upstream with light

freight and fuel with the paddle wheel still "sufficiently immersed to

take up the power of the engines without racing." This was accomplished

by providing the boats with tremendous backing power so that sharp

turns, narrow channels and swift currents could be negotiated without

having to depend on the rudder alone. This backing power was not only

used to reduce the speed of the boats on downstream trips, but to aid in

steering as well.

75 Although it was built at Bennett, operated on the upper river and

named for Canada's minister of the Interior, the Clifford Sifton

was not a typical upper river boat. It had much in common with the lower

river genre, an anomaly explained by it having been built and owned by

a Kansas syndicate.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

76 Known affectionately as the "Old Gray Mare," the steamer

Whitehorse plied the Yukon River for 53 years —

longer than any other boat in the northern fleet. Built in 1901

and rebuilt in 1930, it operated until 1953. It was destroyed

by fire in 1974.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

77 Loading fuel onto the for'deck and into the freight house of

a sternwheeler. Deckhands were on call 24 hours a day to perform

this task. The hand trucks held approximately one-third of a

cord of wood.

(Photo by B. Lesyk.)

|

To compensate for the "slide" of a single rudder, the company devised

a system utilizing six rudders, three behind the paddle wheel and three

between the wheel and the hull, that were controlled by a steam steering

gear. This system permitted the efficient use of the steering apparatus

whether the boat was going backward or forward. As a result, the

steering of these vessels did not depend "as in other craft, on having

steerage way; but on the movements of the stern

paddle-wheel."35

While the boats used by the British Yukon Navigation Company differed

in size and capacity during this era, they did not, in most cases,

exceed 170 feet in length or 35 feet in width. The larger ones carried

between 200 and 250 tons of cargo on a draft of 4 feet. When empty they

drew approximately 18 inches. On the downstream run they averaged 15

miles per hour, covering the distance between Whitehorse and Dawson in

two days. The upstream voyage took four days. The boats had electric

generators and were provided with spot beams to permit night travel

during the period following break-up and just before freeze-up. The

beams were only used on the upstream trip, however, because the swift

current on the downstream run made night travel too hazardous. During

the summer when darkness was not a problem, the boats were in operation

24 hours a day. Freight was carried on the main deck for ease of

handling, with the result that the main deck came to be known as the

"freight house." The engine room and boiler were also located on the

main deck, in the stern and bow respectively.36

These boats carried up to 150 passengers who were accommodated on the

observation and upper decks. Passenger compartments were called

staterooms, a term that originated with the Mississippi steamboats where

the custom had been to paint the names of various states over the door

to each room. Accommodation on the upper deck was generally of a higher

quality than that of the observation deck and the term "Texas," which

also derived from the Mississippi, was used to designate it. Above the

Texas deck was the pilot house. Each boat was provided with a dining

room and liquor was served.37

The British Yukon Navigation Company sternwheelers burned wood for

fuel. On the downstream trip only a limited quantity of fuel was

required for "backing" and steerage. Upstream these vessels consumed

between one and one-half and two cords of wood per hour. Each fall, wood

contracts were let to various individuals living along the riverbank who

cut and stacked timber at regular intervals on the sternwheeler route

for use the following summer. In 1904 the company conducted experiments

with local coal, but its quality was not high enough to justify

converting the sternwheelers into coal burners.38

Despite the many innovations in sternwheeler technology that occurred

as a result of the formation of the British Yukon Navigation Company,

certain characteristics of the Yukon River continued to plague

navigation. Shifting channels, bars and reefs did not disappear with

modifications in the technology of the sternwheeler and efficient

operations continued to demand experienced boatmen and pilots who were

adept at "reading the water" — recognizing the shifting channels

and other impediments to navigation by breaks in the surface and by the

colouring of the water.39 Several techniques were developed

in order to assist the movement of the sternwheelers through difficult

sections and several improvements were made to the river itself.

Of the former the most generally employed was a modification of the

"tracking" technique known as "lining." To track a boat, a number of

men, proportional to the weight of the boat and the strength of the

current, walked along the bank with ropes or track lines, moving the

boat by pulling these ropes in the desired direction.40

Lining a boat followed the same principle, but applied machinery to the

task instead of muscle. When a sternwheeler reached a section of the

river where lining was necessary, a row boat with a flexible cable was

despatched to a point where the cable could be made fast. (Later,

permanent cables were installed where necessary.) If a well-embedded

tree were not available, a "deadman," or heavy log, was set. With one

end of the cable attached to the deadman and the other end tied to the

steam capstan on the boat, the sternwheeler hauled itself through on the

cable. When additional power was required, a "strop" was put on the

cable and a "purchase tackle" was attached to the capstan, a procedure

that had the effect of increasing the power of the capstan from two- to

fourfold.41

Because of the shallow water and shifting channels, sternwheelers

often went aground. When this occurred the backing powers of the paddle

wheel were utilized in an attempt to wash away the bar. If this tactic

were unsuccessful, resort was made to lining or "sparring." Each boat

was equipped with two spars, the ends of which were placed under the

hull of the boat, one on each side when sparring was required. Once set,

the spars were held in position by swinging derricks. Atop each spar was

fastened a three-sheave block held in place by a heavy wire strop, while

corresponding blocks were made fast to the port and starboard sides of

the ship. Tackle ropes were then run from the spars to the steam capstan

on the fo'c'sle. As the capstan drew the ropes, most of the boat's

weight was transferred to the spars. This done, the engines were started

and the boat lurched ahead "like a sick grasshopper," the procedure

being repeated until the boat was off the bar.42

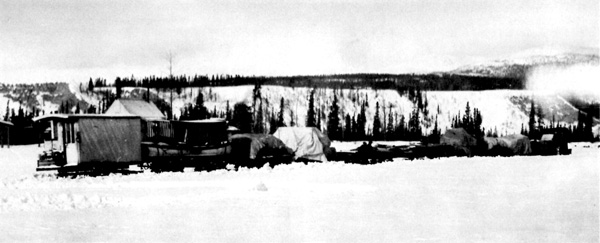

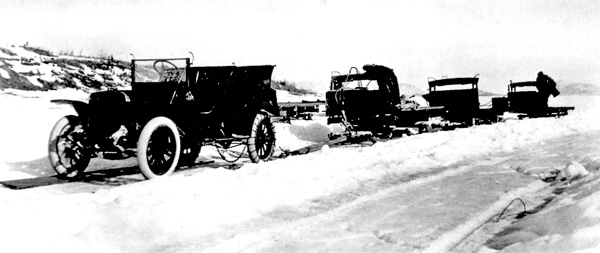

78 Hauling supplies over the ice on Lake Laberge in the spring

for transhipment by boat to Dawson. For many years the British

Yukon Navigation Company wintered a boat at Lower Laberge to

take advantage of the fact that the river below Laberge opened

two or three weeks earlier than the lake.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

With the conversion to capital-intensive mining, the building of the

Klondike Mines Railway and the displacement of the lower river by the

upper route, new methods of heavy freight transport were developed to

handle machinery that could not be loaded onto the deck of a

sternwheeler. Beginning in 1903, scow-assisted sternwheeler transport

became extensive, only to be replaced the following year by small

barges. Large barges were introduced in 1905 and served to increase

carrying capacity to some 450 tons during high water. After that the

pushing of barges became an integral part of the movement of freight on

the Yukon River. Given the river's shallow and crooked nature, this

necessitated the use of "jackknifing" in order to negotiate sharp

turns. To jackknife a boat through a turn, the barge was angled over the

shallows while the sternwheeler was kept in the

channel.43

Another practice adopted by the company, in this instance to extend

the navigation season, was to winter a sternwheeler at the foot of Lake

Laberge. The ice on the river below Laberge broke up before the ice on

the lake went out and wintering a vessel at the foot of the lake added

about two weeks to the short navigation season. Employing men to look

after the sternwheeler during the winter months increased the costs of

an otherwise seasonal operation and the charges incurred by the cartage

of freight over the ice of the lake to supply the sternwheeler offset

many of the advantages that were gained by extending the navigation

season.44

The feud between transportation and the river was not an entirely

one-sided contest. The river, too, was forced to concede some of its

natural superiority as men sought ways to make it more amenable to the

movement of traffic. Between 1900 and 1914 the government sponsored a

series of river improvements — at times independently and at other

times in league with the navigation companies operating between

Whitehorse and Dawson — to eliminate the most difficult obstacles

to navigation on the upper route.

One of the first of these improvements was the construction of a

breakwater by the Department of Public Works at the head of Lake Laberge

in 1899-1900. The breakwater proved inadequate, however, when in

1902 the ice carried a portion of it away and the channel reverted to

its old course.45 This section continued to be a problem

requiring annual work until the British Yukon Navigation Company built

a dam at Marsh Lake in the early 1920s.

In 1900 a portion of the rock outcropping at Five Fingers was blasted

in order to widen the east channel. Two years before, the stampeders had

installed a windlass there to line their boats through, an improvement

that had its limitations since it was restricted to use by small scows.

In 1904 a cable was laid through the Five Fingers to assist

sternwheelers on the upstream run. For years the Department of Public

Works worked on the Five Fingers, dynamiting the rock formation until

the channel was widened by some 20 feet.46

In 1900 one official reported that "during low water heavily loaded

steamboats touch the bottom of the river" at Hellsgate. In 1902 the

government built a dam there to deepen the channel. By

1908 the dam had deteriorated to such a degree that it was necessary

to refill it and improve the breakwater.47 In the same year,

the British Yukon Navigation Company expended a government appropriation

of one hundred thousand dollars removing the rock and reef obstructions

at Rink Rapids.48

Taken together, the innovations in sternwheeler technology, the

utilization of a variety of navigational techniques and the river

improvements greatly reinforced the vital role played by the

sternwheeler in the economy of the territory between 1901 and 1914, a role

that had had its awkward beginnings as early as 1866 and was to last

until 1950.

Like the mining industry to which it was so closely tied, river

navigation underwent a painful period of readjustment during the first

14 years of the century. When the gold rush ended, most of the river

transport companies on the upper river ceased operation, but the

collapse of the gold-rush economy did not herald the end of the

sternwheeler, A new company emerged which for the first time had come to

the Yukon to stay.49 The effects of this commitment were

far-reaching. For the first time boats were built in the Yukon and the

sternwheeler was adapted to suit the limitations of the river.

Carpenters, engineers and crews, if only in small numbers, were given

employment where before there had been none. The investment of the White

Pass and Yukon Route in its transportation facilities meant that the

company had a practical interest in the economic development of the

territory that was not simply restricted to the high-grading type of

exploitation that had prevailed before. Finally, the company's

commitment gave to the Yukon a degree of stability and assurance unknown

during the gold rush.

The sternwheeler was more than a carrier of men and supplies into and

out of the territory, It was an active participant in the mining

conversion. It supported the timber industry by burning wood for fuel

and united the small communities that hugged the riverbank. By 1914 it

was an integral element in the life style of every Yukoner.

79 SS Klondike No. 2 lining through Five Finger Rapids.

The cable was picked up with a pole and wrapped around the winch

drum. Power was then applied and the boat pulled itself through.

(Photo by B. Lesyk.)

|

IV

From the day it was completed, the Skagway-Whitehorse railway proved

to be a remarkably profitable enterprise. One contemporary alleged that

the entire cost of construction was liquidated during the company's

first year of operation. In 1901 and 1904, two years for which figures

are available, the company's net earnings were $1,500,000 and $451,000

respectively. Until 1912 the White Pass and Yukon Route returned a

dividend at the end of each fiscal year to its investors, a return that

reflected the intensive utilization of the railroad's facilities.

Through 1911 as many as three trains a day, except Sunday, were run

between Skagway and Whitehorse during the summer months, while in the

winter, when the river was closed to navigation, there still existed

sufficient demand for the company to operate an average of six trains a

week.50

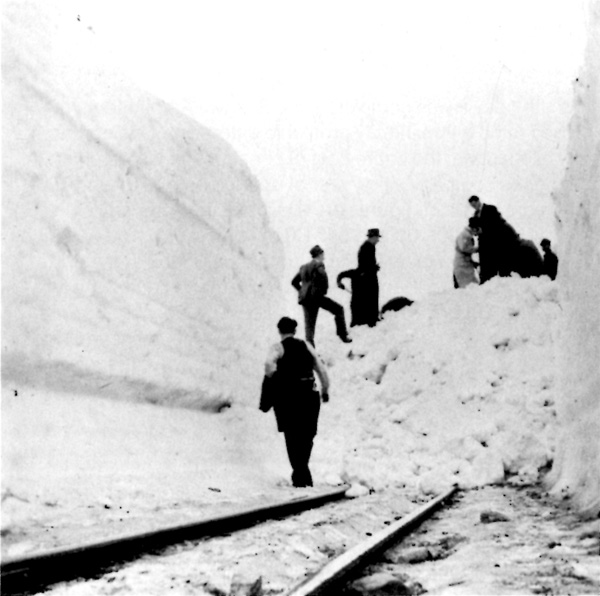

The Yukon winter provided the railway with its severest test during

these years. Each November the annual struggle between the railway and

the elements commenced, a struggle which lasted until April of the

following year. And every year the winter extracted its toll from

roadbed, rolling stock and train crews. No other railway on the

continent pushed through such extremes of winter climate in 110 miles.

From Skagway to Bennett high winds and heavy snows prevailed. On the

section between Glacier and Bennett the snow depth often reached 25 feet

and severe winds frequently drifted it 25 more. From Bennett to

Whitehorse the snowfall decreased as temperatures plunged, sometimes

reaching 60 degrees below zero. In the spring, snow slides and washouts

wreaked havoc with the safe movement of passengers and freight and

demanded the engineers' constant vigilance. To deal with these

conditions, the company maintained two rotary snow-plows and erected a

series of massive snow fences on the Canadian side of the summit to

keep the line clear, but even these precautions did not eliminate the

need to use train crews armed with no more than shovels to free the

tracks after a particularly heavy snowfall.51

Apart from its "life line" function to the Yukon interior, the White

Pass and Yukon Route exploited to advantage one of the two new resources

that were discovered during this period. The first comprised the summer

tourist trade, a trade that was to increase significantly over the

years, becoming a mainstay of the railway during the desperate years of

the 1930s. The lure of the Klondike was still powerful during this

period, as the popularity of books on the gold rush demonstrated, and,

moreover, was more than matched by the spectacular scenery that ringed

both sides of the rail line between Skagway and Whitehorse and

highlighted the sternwheeler excursions operated by the company to

Atlin, British Columbia. Arrangements were made with the coastal

steamship companies operating into Skagway to exploit this colourful

history and splendid scenery. On the two-day stopovers at Skagway made

by Canadian Pacific Railway steamers, the White Pass and Yukon Route ran

tourist excursions into the interior, while on the one-day stopovers

scheduled by the Alaska Steamship Company and the Pacific Steamship

Company, the White Pass and Yukon Route operated special return-trip

excursions to Bennett Lake.52

The second resource to be exploited was the copper deposits

contiguous to Whitehorse. As early as 1897 several outcroppings of

copper had been reported by prospectors stampeding to the Klondike and

in 1898 the first claim was staked. For the next nine years exploratory

work and occasional shipments of copper ore were made, but poor

transportation facilities based on a wholly inadequate road system

pushed costs to prohibitive levels. In 1907 production was increased

substantially, reaching a level of 3,530 tons. In the same year the

White Pass and Yukon Route decided to build a spur line from MacCrea,

seven miles south of Whitehorse, to the Valerie, Arctic Chief, Grafter,

Best Chance, Spring Creek, Pueblo, War Eagle, Copper King, Rabbit's Foot

and Anaconda copper properties. Construction was begun in 1907 and

continued through 1908. A sharp decline in production in 1908 followed

by the cessation of production in 1909 resulted in a construction

stoppage for 16 months. The failure of these mines during 1908-09 has

been attributed by one writer to "the high freight rates charged by the

White Pass and Yukon Route railway and the inadequacy of transportation

facilities between the mines and Whitehorse."53

Work resumed on the 12-mile spur line in 1910 and the final four

miles were completed to the Pueblo property in August. Beginning in

1911, daily ore trains were operated on a year-round basis. A reduction

in the White Pass and Yukon Route freight schedules in 1912 was a

significant factor in bringing the mines back into production.

Production increased at a rapid rate during World War I following a rise

in the world price of copper, but the cessation of hostilities depressed

the price of copper, and brought into focus once more the delicate

balance between transportation and profitable mineral production in the

Yukon. Like the gold rush, the First World War camouflaged the basic

problems that underlined the Yukon economy. Inflation and increased

demand more than compensated for the high costs of production and

transportation over the short term. Yet the gold rush and the war were

events of short duration and once the specific demands they had

engendered disappeared and normality returned, the cost-price dilemma

reappeared in high relief. After the war, copper production practically

ceased and the spur line was abandoned.54

80-81 Men and machinery battle snow on the White Pass and Yukon

Route.

(Photos by J. Dunn.)

|

The adverse effect of transportation costs on the successful pursuit

of enterprise in the Yukon was not restricted to the nascent copper

industry. The experience in the Klondike district, while different in

one essential respect from that of the Whitehorse copper mines,

reflected the same basic transportation problems. What distinguished the

former from the latter was not the nature of the transportation burden,

but its distribution. In the latter case, transportation costs had been

borne directly by the copper industry as a result of a small,

producer-oriented population and the bulk characteristics of the mineral

produced. In the Klondike the transportation costs were borne by the

entire community. The reason for this was simple. In the case of

copper, the standard of value was price per ton, while with gold, value

was measured in ounces. Whereas in the copper industry the

transportation costs were borne by the outgoing traffic, in the Klondike the

transportation costs were borne by the incoming traffic and as a

consequence, the whole community was affected — producers, by

virtue of the need to pay higher wages in order to compensate for the

higher cost of living, and consumers, who covered the transportation

charges in the price they paid for each product they

purchased.55

Grievances, real and imagined, against the schedule of freight rates

published by the White Pass and Yukon Route were a constant refrain

during this period — and indeed have remained so to the present

day. The railway did not effect a massive reduction in transportation

costs; rather it made transportation faster, easier and more

reliable.56 Apart from the criticism of tariff schedules that

sprang from legitimate complaints, the White Pass and Yukon Route's

virtual monopoly on traffic into the interior made the company more

vulnerable to attack than would have been the case had competitive

conditions prevailed.

After the collapse of the gold-rush economy, the population of the

Klondike district declined. This decline was followed, in turn, by a

corresponding decline in business. "As a result... attempts were made to

reduce costs and particularly costs of transportation." There followed a

period of agitation for a reduction in the freight rates charged by the

White Pass and Yukon Route. As early as 1901, the company was ordered to

lower its rates by the dominion government. Continued economic

contraction after 1901, however, offset the immediate benefits of the

reduction and attacks on the company's rates increased in intensity.

In 1905 the Dawson Board of Trade argued that the future of the

territory depended on transportation costs being low enough to work

profitably the remaining low-yield gravels and it condemned the White

Pass and Yukon Route for its "extremely exorbitant freight and passenger

rates [which it is able to charge] by reason of an unjust monopoly . . .

[thereby] injuring the entire business interests, [and] hampering and

retarding the . . . development of . . . mining." Citing evidence that

three-eighths of the territory's production was consumed by

transportation costs, the board demanded that the company either be

ordered to halve its existing rate schedule or that the government

subsidize a competing line. This resolution attracted the support of the

Young Men's Liberal Club in Dawson and the commissioner of the

territory.57 Yet despite this widespread support for the

Board of Trade recommendations, the resolution was not acted upon by

Ottawa.

An indication of the exorbitant tariff charged by the White Pass and

Yukon Route is suggested by a comparison of various commodity costs and

the freight rates charged for the transport of these items between

Skagway and Whitehorse in 1910. In several instances the freight rates

exceeded the wholesale cost of the product. The high tariff schedule can

be partially explained as owing to the remoteness of the territory from

the major centres of supply. Nevertheless, it is also true that the

directors of the White Pass and Yukon Route recognized that the days of

the "fast buck" in the Yukon were over and they followed a conscious

policy of "getting all that they could, while the getting was good." The

shareholders extracted every last possible profit from the operation,

oblivious to the needs of the Yukon and to the detriment of the physical

facilities of the railway. In two actions against the company, management

was charged with corruption. Finally, in 1911 the Board of Railway

Commissioners ordered the White Pass and Yukon Route to reduce its

freight rates by one-third.58 An appeal to the Privy Council

instigated by the company, however, resulted in the granting of a new

hearing. At the rehearing the board reversed its first decision and

instructed the White Pass and Yukon Route to make a voluntary rate

reduction.59 The company accepted this order and lowered its

rates approximately ten per cent.60

Reaction to the reversal of the board's first judgement was swift

within the territory. George Black, the commissioner, wrote that the

reversal "has not had a tendency to encourage prospecting in the

territory" and emphasized that the question of transportation costs,

with special reference to the White Pass and Yukon Route, was "a matter

of the utmost importance to all persons prospecting and mining in the

Yukon; in fact, to all inhabitants of the territory, as all lines of

business are absolutely dependent on mining."61

V

Transportation in the Klondike district, based as it was on the

horse, the dog and a hodge-podge network of poor roads and trails,

seemed wholly inadequate to handle the traffic requirements of the

region after 1901.62 The conversion to capital-intensive extractive

techniques and the eruption of a number of communities on the

gold-bearing creeks created the need for a form of transportation —

more reliable on the one hand and more capable of moving heavy freight

and machinery on the other — to satisfy the changing

transportation requirements of the district. As had previously been the

case on the Panhandle access route to the territory, the solution to the

problem of traffic movements was found in the construction of a

railway.

As early as 1897-98, serious consideration had been given to a

proposal to build a railway connecting Dawson with the communities that

were springing up on the placer creeks. In July of 1899, this proposal

was acted upon and the Klondike Mines Railway Company, with its head

office in Ottawa, was incorporated. Under the terms of the act of

incorporation, the railway was to originate in Klondike City, across the

Klondike River from Dawson, skirt Bonanza and Dominion creeks to Indian

River and return to Dawson via the east bank of the Yukon River. Between

1899 and 1903, when construction actually began, the location of the

line underwent several changes. The "loop concept" established by the

act of incorporation was superseded by another plan to locate the

railway from Klondike City to the headwaters of the Stewart River a

distance of some 85 miles, a plan that was superseded in turn by the

promoters' decision to run the line from Klondike City to Sulphur

Springs.63

The elimination of Dawson from the promoters' plans elicited a

variety of protests from that quarter. William Ogilvie, in a letter to

the minister of the Interior, expressed incredulity at the selection of

Klondike City rather than Dawson as the terminus, citing the former's

poor steamboat landing, absence of wharfage and warehouse facilities

and lack of good land suitable for development and expansion purposes as

reasons why Klondike City should not be chosen. Why Klondike City was

chosen over Dawson can probably best be explained by noting that one of

the promoters, Thomas O'Brien, owned a substantial amount of property

there. O'Brien, moreover, had already demonstrated a facility for using

transportation projects as a means to fast money, as the Pioneer Tramway

Company debacle clearly showed. One of the most colourful figures of

the Klondike's first decade, O'Brien was the proprietor of a brewery

in addition to his other interests and he played

an active role in the political squabbles of the period, oddly enough as

a reformer.64

As protests over the terminus mounted in 1902, the promoters of the

railway — O'Brien, W.W. Parsons and E.C. Hawkins — agreed to

appear before the Dawson city council. As a result of this meeting, the

promoters were persuaded to designate Dawson as the terminus and a

franchise was conferred on the Klondike Mines Railway Company for the

laying of track and the building of a station on Front Street in

Dawson.

The series of miscalculations, beginning with the locational and

terminal difficulties which had taken four years to sort out, continued

into 1903 when for the first time a considerable amount of grading was

done and four miles of track were laid and subsequently abandoned. By

September of 1905, however, the first of two sections of bridge over the

Klondike River was completed and work was well advanced on the second.

Then a new problem, this time over the right of way, appeared.

Injunctions obtained by the claim owners on Bonanza Creek forced the

company to abandon construction on that section. The fear, previously

expressed as early as 1901, that the right of way of the rail line would

interfere with a large number of working claims, had materialized.

Mindful of the crisis that now existed, the federal government

despatched a representative of the railway commission to make a full

investigation into the matter.65

Once the controversy over the right of way had been sorted out, the

railway was quickly completed. Three locomotives were purchased from the

White Pass and Yukon Route and by November 1906, trains were operating

on the 31-mile line between Dawson and Sulphur Springs via Grand Forks.

The total construction cost of the narrow-gauge railway was estimated at

two million dollars. Under the terms of an agreement signed on 25 May

1906 the Klondike Railway qualified for a government

subsidy.66

After the railway was completed, the horse-drawn stages that had

previously run between Dawson and Grand Forks were discontinued. Service

to the creeks tributary to the rail line was provided by daily passenger

stages and freight wagons operated by the railway company.

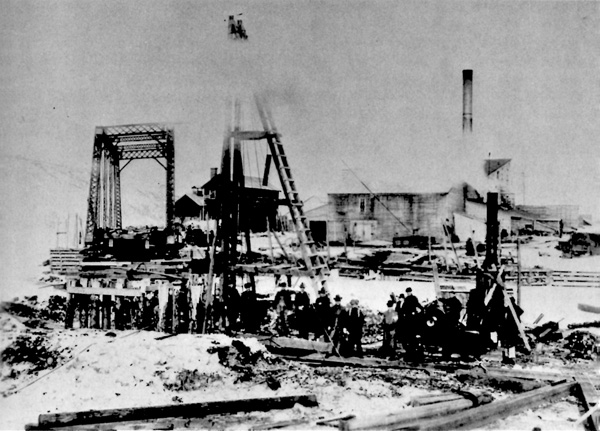

82 The steamboat landing at Klondike City, steamers Lightning

and Tyrrell in the foreground.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

83 A Klondike Mines Railway train en route to the creeks with a

load of timber. Dawson is in the background.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Unlike the White Pass and Yukon Route railway, the Klondike Mines

Railway encountered severe financial difficulties from the very

beginning. After 1906-07 the company abandoned winter operations for

reasons of economy. In 1909 the directors reported that expenditures

exceeded revenues by 100 per cent and petitioned the territorial council

for financial aid. The council responded by granting assistance for a

period of two years. Nevertheless, it was apparent by 1909 that placer

mining could not sustain the railway much longer and, as the general

manager of the Klondike Mines Railway Company put it, "the future of the

railway hinge[s] on [the] development of quartz mining." But quartz

mining never progressed beyond the optimistic appraisals that were made

for it and by 1913 the railway's operations were curtailed to the

12-mile section between Dawson and Grand Forks. Finally, in July of

1914, the company abandoned operations completely.67

An analysis of the failure of the Klondike Mines Railway underlines

one of the many problems involved in any study of the Yukon.

Superficially, the company's failure could be attributed to the economic

decline that characterized the period from 1900 to 1914. However,

assuming the promoters felt (as they must have) that the railway could

make a profit, even as late as 1904 when construction could have been

abandoned, and taking into account the fact that between 1907 and 1914

gold production exhibited a moderate but uninterrupted upswing, it seems

clear that the reasons for the failure of the Klondike Mines Railway

Company are not to be found in declining gold production but rather in

the nature of gold mining itself.68 The conversion to

capital-intensive mining which the railway facilitated reduced the need

for transportation of the type provided by a railway. The railway relied

upon continuous, revenue-producing operation in order to show a profit

whereas capital-intensive placer mining in the Klondike required rail

service on an irregular basis. The conversion to machine-orientated

mining, moreover, was concentrated in an area adjacent to the railway's

right of way. The acquisition and consolidation of individual claims

into concessions, an integral part of this conversion, led to a decline

in population in the creek communities served by the railway and was

followed by a coincident decline in transportation revenues. In the end,

the very dredges that the railway had helped to transport to the creeks

proved to be its nemesis. When quartz mining, the development on which

many in the Klondike had pinned their hopes for the future, failed to

materialize as a satisfactory alternative to placer mining, the

railway's fate was sealed.

VI

After 1900 the importance of roads and trails as a transportation

factor increased enormously. The period when inflated prices and wages

had compensated for inadequate domestic overland transport disappeared

with the passing of the gold rush, and the construction of new roads

and the improvement of old ones marked a deliberate attempt on the part

of the territorial authorities to reduce transportation costs to a level

commensurate with new economic conditions.

Road building in the Yukon was complicated by three things:

the nature of the territorial economy, the climate and the terrain

over which roads were located and from which material was taken to build

the roads themselves. Because the economy during the period

1900-14 was based on a single nonrenewable resource that was easily

exhausted, many roads became obsolete shortly after they were built. As

the frontier of mining activity expanded, especially in the Klondike

district, new roads were required to link the new working properties

with Dawson, the transportation and supply hub of the region. In

general, the territorial authorities were responsive to the demands for

new roads of this type and increased expenditures for road construction

"in order to keep pace with the new conditions and assist in the rapid

development of our mining interests" were made as a matter of

course.69 But where roads were required for exploration and

prospecting purposes with no guarantee that any discoveries would in

fact result, government assistance was negligible, in keeping with the

peculiar concept of laissez faire characteristic of the times. Another

problem directly related to the territorial economy concerned the

location of roads. Typically, a road was built to follow the path of

least resistance, in most cases a creek bed, where maintenance costs

were generally higher as a result of poor drainage, but where the cost

of construction generally was low. While it might have been more

expedient in the long run to build roads along the hillsides, other

considerations outweighed the advantages to be gained from doing so.

Construction costs would have been increased enormously. In the Yukon,

where economic prospects dimmed between 1900 and 1914 and where the life

span of a road depended on the richness as well as the concentration of

a mineral deposit, the risks were too great to justify this added

expenditure. Because the mineral deposits and the techniques of

extraction were generally of the placer type, the deposit tended to be

"worked out" much more rapidly than a lode deposit of comparable value.

Given this built-in obsolescence, quantity rather than quality came to

be the determining factor governing policy. The soundness of this

approach was vindicated by the fact that road locations were constantly

being modified to meet the changing needs of the mining community. Since

roads were built to serve the mining industry, not vice versa, the

location of a road was altered whenever it came into conflict with the

location of a working claim.

84 A Klondike Mines Railway train and the Yukon Gold Company's

Dredge No. 1. Dredging presaged the end of the railway.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

85 A 20-horse team hauls a dredge spud weighing 27 tons

to Bear Creek from Dawson.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

The Yukon winter was not as serious an obstacle to road transport as

might be initially suspected. In fact, road conditions were poorest

during the spring and fall with the result that in July 1902 the

territorial council passed an ordinance restricting vehicles to two

horses between 15 April and 31 May, and 15 September and

31 October, and stipulated the use of four-inch tires on heavy

wagons to prevent road damage.70 Hard-packed snow furnished

the Yukon road system with its best surface of the year, facilitating

the movement of people and supplies as well as the principal agents of

motion, horses and dogs. After 1900 a network of "winter trails" was

developed to supplement existing wagon roads. These trails were 75 to 90

per cent cheaper to build than conventional roads, requiring only the

removal of brush and trees, and snow providing the surface.71

They furnished remote communities off the water routes with better

access to Dawson during the winter than at any other time of the year.

The adverse effects of winter on the regular roads occurred during the

spring, when the spring runoff turned roads into virtual swamps,

sometimes causing slides and washouts. It was not until asphalt became

a practical alternative to gravel at a much later date that winter

proved to be a serious deterrent to road rehabilitation and

construction.

Apart from the economic factors that governed policy, the most

serious obstacle to road construction involved the terrain over which

roads were built. The existence of permafrost required techniques of

road construction that were quite different from those that were used

south of the 60th parallel.

Permanently frozen ground, or permafrost as it is commonly called,

lies under a layer of overburden known locally in the Yukon as "muck."

This overburden acts as an insulator, protecting the frozen ground from

the heat of the sun's rays and effectively inhibiting melting. If

removed as a preliminary to the preparation of a roadbed, the permafrost

will melt, causing a softening of the subgrade and making for an

unstable road surface. Fortunately, the economics of road building

between 1900 and 1914 generally precluded any ambitious attempt to

remove the overburden and therefore permafrost did not prove to be a

serious problem. In cases where the overburden was removed inadvertently

or through ignorance, the subgrade could be repaired by re-covering the

exposed permafrost with an artificial overburden of brush and

vegetation. While road builders in the Yukon learned through trial and

error not to tamper with permafrost, those involved in the construction

of the Alaska Highway did not have the benefit of this experience. As we

shall see in a later chapter, one of the major problems encountered

during the construction of the highway derived from a lack of knowledge

concerning the nature of permanently frozen ground.

Along with permafrost, certain soil properties geologically

characteristic of the Yukon added to the already difficult task of road

construction. When available, gravel was used for road surfaces. Gravel

was not always possible to obtain, however, forcing road contractors to

substitute whatever was available, glacial mud,

clay or decomposed schist. None of these alternatives were particularly

satisfactory. Clay and glacial mud were adequate so long as

the road was so drained that water could not combine with them. When it

did, the surface became a quagmire, practically impassable. Decomposed

schist, on the other hand, lacked binding sediment and required constant

grading and maintenance to keep it up.72

Ideally, wagon roads were constructed on a stable earth base covered

with broken stone or gravel, the former being preferred. Once the

surface had been laid, it was graded. Heavy grading required six to

eight horses. If the roadbed were well drained, the road could handle

heavy traffic with minor maintenance. On swampy ground, depressions and

muskeg were corduroyed and covered with earth. This type of road, unlike

the gravel type, required continuous maintenance because the earth

surface deteriorated rapidly under heavy use. Corduroy was also used on

main thoroughfares where gravel was not accessible. Timber for bridges

and culverts was cut from native spruce and lasted for eight to ten

years under stress. Wagon roads varied in cost from $1,500 to $3,300 per

mile, substantially more than the $250 to $350 per mile expended on

winter trails.73

Because of the climate, the terrain and the economics of road

construction, maintaining the territorial road system was as important a

factor in the overland transportation system as the construction of

roads themselves. Roads were poorest in the spring, a result of winter

icing and the spring runoff. To counteract winter icing, road crews cut

and maintained ice trenches during the winter to concentrate the water

and to prevent, so far as was possible, damage to the road. In addition

to this, ice formations or "glaciers," as they were also called, were

cut and the roads were kept plowed. During the spring, maintenance crews

were at their busiest: protecting roads from the spring runoff; removing

snowdrifts, snowslides and other debris from the road surface; opening

up culverts and waterways, sometimes by steam thawing; diverting water

away from roadbeds to prevent washouts, and repairing damage resulting

from water sluicing. Yet despite these preventive and cleanup measures,

the arrival of spring continued to be attended by a general

deterioration of the territorial roads. As one official observed, "the

very conditions which put roads in bad shape will hinder any steps being

taken towards their permanent improvement until such time as the snow is

melted and the ground thawed." During the summer, maintenance crews

repaired ditching, replaced gravel, regraded road surfaces and built up

shoulders and soft spots. Bridge cribbing was ballasted or renewed and

decking was replaced when necessary.74

86 Roads and trails in the Klondike and Mayo districts.

(Map by S. Epps.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

The innovations in mining technology that occurred on a large scale

after 1903 added a new dimension to the maintenance problem. Hitherto,

maintenance crews had concerned themselves almost exclusively with those

problems resulting from the action of natural forces. The effect of

hydraulic monitors and dredges on the contour of the land, however,

exacerbated the already large task involved in maintaining the road

system. Tailings from both operations changed existing drainage systems

and buried roads. Problems of this nature were especially acute on the

Bonanza Creek road where tailings filled water channels, producing

winter icing and spring washouts.75

Between 1900 and 1914 some fourteen hundred miles of road were

constructed in the Yukon Territory. The majority of these roads were

built to give access to groups of working claims and to link small

communities with the closest supply centres. As a general rule they

were built to complement river transportation routes. In only a few

isolated cases were roads constructed for what would now be called

development purposes.76 Geographically, roads were of two

types: intradistrict roads and interdistrict roads. The former were

built within each of the mining districts established by the Mines

Branch of the Department of the Interior (the Dawson or Klondike, Duncan

or Mayo, and Whitehorse districts). These roads had a regional rather

than a territorial significance, their function being determined by the

special requirements of the individual district in which they were

built. The interdistrict roads, on the other hand, were those that

connected one mining district to another.

In terms of mineral production and population density, the Klondike

district was the most important district during this period and it was

there that road and trail construction was concentrated. Before the

Klondike district was provided with an adequate network of roads and

trails, however, a solution to the problem created by Dawson's location

had to be found. Cut off from the centres of mining activity by the

Klondike River to the south and by the Yukon River to the west, Dawson

required substantially improved connections over both before a

satisfactory road programme could be undertaken. The first step toward a

solution to this problem was taken in 1900-01 with the construction

of the Ogilvie Bridge over the Klondike River. The bridge's 155-foot

steel span replaced the cable ferry that had previously carried traffic

across the river. Once completed, road construction proceeded

vigorously. By 1914 the Klondike district was covered with a network of

roads serving the main creeks and their tributaries. Of these, the

principal were the Ogilvie Bridge road, the Bonanza-Indian River road,

the Hunker-Dominion road, the King Solomon Dome-Sulphur road and the

Klondike road. Stages and freighting

outfits operating out of Dawson used these roads to supply the stores

on the creeks and to deliver mail and newspapers to the people who lived

there.77 Between 1906 and 1914 the Klondike Mines Railway

competed with roads contiguous to its right of way, but the economic

difficulties that plagued it and the curtailment of its winter

operations after 1907 resulted in the railway having only a negligible

effect on road transportation in the district as a whole.

Another region for which Dawson acted as a transfer point was the

Sixty Mile mining district, located on the west side of the Yukon

River. Although the gold rush had resulted in a rapid decline in the

importance of this area, prospecting and mining had continued there,

especially on Glacier and Miller creeks. In order to afford improved

communication between Dawson and these creeks, a cable terry was built

across the Yukon River at Dawson in 1902.78

The cable ferry was an ingenious expedient applied to the problem of

crossing rivers in the Yukon where economic circumstances did not

justify the erection of a bridge. Until the end of the Second World War

when roads rapidly superseded water as the primary highways of

transportation, the cable ferry was the most common form of river

crossing in the territory. A relatively simple device, the cable ferry

consisted of a steel cable strung between two towers on each side of the

river. A scow was attached to the cable with a sliding bridle tied to

two cleats, one near each end of the same side of the scow. By adjusting

one side of the bridle with a tightening or a loosening action, the scow

could be angled into the current so it would travel in the desired

direction, the current providing the motive force.79

All traffic moving west of Dawson was taken across the river on the

cable ferry. The scow had a six-horse—one-wagon capacity. When the

cable ferry could not be operated safely — generally at the

beginning or at the close of the navigation season — a canoe was

used instead.80

The erection of the cable ferry resulted in an increase in the volume

of traffic over the river. In 1902 a pack trail that had been cut the

previous year from West Dawson to Glacier was brought up to the standard

of a "passable" wagon road. Increased mining activity in the area over

the next two years was followed by the construction of a good wagon road

in 1904. This new wagon road, in turn, had a salutary effect on mining.

During the winter a sled trail was used to connect Glacier and