Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 13

All that Glitters: A Memorial to Ottawa's Capitol Theatre and its Predecessors

by Hilary Russell

The Circuits

In the same year as RCA Photophone was organized, the Radio

Corporation of America (RCA) bought the theatre chain interests of two

of the biggest vaudeville circuits, B. F. Keith and Orpheum, as well as

the film producing company FBO or Film Booking Office owned by Joseph P.

Kennedy. The deal was officially closed in February 1929. The new

company, Radio Keith-Orpheum (or RKO), was firmly established in the

industry both in exhibition and production. The amalgamated theatre

circuits provided outlets for "Radio Pictures," the sound movies of the

producing company.1

In Canada, the merger was compounded by an agreement reached in 1929

whereby RKO and Famous Players Canadian Corporation formed a new

company, Radio Keith Orpheum Canada Limited, to operate 12 first-run

houses. Ottawa's RKO Keith theatre was included in the deal.2

The theatre became the RKO Capitol in 1931: as Famous Players eventually

supplanted RKO, a few years later, the initials RKO were discarded.

It would be an oversight to write about the history of Canadian

exhibition without reference to the circuits that controlled most movie

palaces and other important houses. However, only those circuits that

owned the Ottawa Capitol will be examined in detail.

In the United States and Canada, circuit ownership had a fundamental

impact on the entertainment presented in a theatre, the decor and size

of the house, as well as on film production in Hollywood. Only large

corporations could afford the investment involved in building movie

palaces. They could retain expensive architects, and could indulge in

the rivalry with other giant corporations which resulted in

progressively more gaudy and outlandish developments in theatre

architecture, decoration, stage entertainment and special effects. With

affiliated exhibitors, large circuits virtually monopolized first-run

exhibition in large urban centres.3

Many circuits were also involved in film production and distribution.

Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, a huge New York-based company enmeshed

in all phases of the movie industry, began to acquire theatres in about

1919 to provide adequate and profitable playing time for the prime

interest, Paramount Pictures. Loew's, on the other hand, entered

production in 1919 to protect vast theatre holdings from Famous Players

films and profits. B. F. Keith's was not involved in film production

until the RKO merger.

The film-producing arms of the companies had guaranteed exhibition in

hundreds of first-run houses, and could finance productions with the

assured box office. The circuits were thus able to squeeze independent

exhibitors out of business or into affiliations. Independent producers

could be denied access to chain theatres, and an independent exhibitor

could be refused popular films or forced to rent a "block" of company

films in order to secure one of exceptional commercial

value.4

B. F. Keith's and other vaudeville circuits maintained booking

offices to provide contracts for vaudeville acts. "High class" acts at

competitive prices were booked mainly into chain theatres with large

seating capacities. The contracted performers, of course, toured the

circuit.

Three vast continental circuits operated Ottawa's movie palace during

its lifetime. The Capitol became the object of interesting circuit

rivalries from the time it opened.

Loew's Ottawa was built as a link in the Eastern Canadian chain of

Loew's theatres which offered vaudeville and photoplays in luxurious

surroundings.

A subsidiary Canadian corporation supervised the venture, which was

at least partially financed through sale of stocks. Some of the

contractors had a vested interest in the theatre: at least one company

was paid in gold-based bonds issued on the first mortgage at 12 per cent

interest. These bonds were cashed at a handsome profit when the theatre

was sold in 1924.5

Loew's Ottawa was one of the last houses in the chain to be built in

Canada. An Ottawa newspaper announced in 1920 that Loew's planned five

theatres in western Canada, but the programme was never carried out. By

the end of 1920, a building boom that had swept Loew's was

over.6

The vaudeville acts Loew's Ottawa presented were arranged by Marcus

Loew Booking Agency in New York. The theatre showed many films made by

Metro Studios,7 Loew's producing company.

The same month as Loew's Ottawa opened, Famous Players Canadian

Corporation announced that the company would open within the next year a

theatre on Queen Street with a capacity of 2,600. The circuit was well

aware that Ottawa probably could not have supported two similar houses

with capacities over 2,500. In these days, it was common for a circuit

to challenge another's new theatre (or the promise of one) by

threatening to build a bigger, more expensive theatre within a few

blocks of the original. In a small town or city, the latter might be

ruined by such competition, and the challenger hoped that this awareness

would prompt the owner to lose his nerve and sell or would encourage a

would-be owner to give up his plans to build.8

Famous Players Canadian Corporation was a homegrown, aggressive

theatre circuit. It had acquired the name Famous Players Canadian and

the franchise for distributing Paramount productions in 1920. Initiated

in 1916 as The Regent Theatre Company and financed by a coterie of

Toronto businessmen, the company prospered, and by early 1919 it owned a

number of theatres in Ontario and had procured another name, Paramount

Theatres Limited, although the circuit as yet apparently had no

connection with Paramount films. These were distributed in Canada by The

Famous Players Film Service, an Allen concern. In June 1919, Select,

Triangle and Metro films were among the major releases handled

throughout Canada by Regal Films Limited, the distributing arm of

Paramount Theatres Limited. (Their officers were practically identical,

J. P. Bickell headed Regal, and its managing director was N. L.

Nathanson.)9

That month, two rumours were published in Moving Picture

World: Famous Players-Lasky of New York would deprive the Allens'

Famous Players Film Service of the Canadian distributing rights for

Paramount pictures in September and would award the franchise to Regal

Films Limited: and the New York company had "acquired a substantial

interest in the theatres controlled by Paramount Theatres Limited." The

magazine's vigilant Toronto correspondent was substantially

accurate.10

Famous Players Canadian was incorporated in January 1920 with a

reported capital of $15 million and an 18-year Paramount franchise.

Adolph Zukor, head of Famous Players-Lasky (later Paramount Publix) was

the president of the new company and, it was later maintained, had

invested $100,000 in the venture. Contemporary news releases

acknowledged that Famous Players-Lasky had made "a large cash investment

in the new Canadian company," but that "the majority of directors" would

be Canadian and "the bulk of the securities and control of the

enterprise would be in Canadian hands."11 Nearly $12 million

in shares was offered to the public, $4 million in first preferred and

the rest in second preferred and common stocks.

Royal Securities Limited of Montreal underwrote the capitalization

for $4 million.12 This finance and bond-selling company had

been sold to W. Killam by Lord Beaverbrook in 1919. Contemporary and

certain secondary sources consulted made the assumption that in 1920

Beaverbrook's spectre was still with Royal Securities.13 The

link between Famous Players Canadian and Beaverbrook appeared the more

real as he had recently acquired "large motion picture interests" in

Great Britain. Moving Picture World recorded an announcement made

in Toronto in March 1920 which went so far as to "understand" that

Beaverbrook was a "heavy investor" in Famous Players Canadian. It

continued, "he was slated for a place on the company's board, but felt

that it would not be good policy to appear as a director."14

Possibly in this instance Beaverbrook's name was being exploited in the

hope of winning investors.

Famous Players Canadian took over the 20 theatres previously operated

by Paramount Theatres Limited, and set its sights on acquiring 20 more.

An extensive building programme was immediately launched, and theatres

were bought or built in Montreal, Peterborough, Toronto, Hamilton, Sault

Ste. Marie, Winnipeg, Regina, Calgary, Vancouver and Victoria.

The building of a Famous Players" Ottawa theatre also got under way.

Its walls had attained a height of ten feet when construction ceased.

Ostensibly, the theatre was placed on the unfair list by the Building

Trades Council of Ontario for not abiding by approved wage

scales.15 Possibly Loew's had called an elaborate bluff.

The contest between Loew's and Famous Players was complicated by the

announcement in 1923 that B. F. Keith's planned to construct a

half-million dollar vaudeville theatre, possibly on Famous Players'

Queen Street site. On the heels of this publicity came the announcement

that Famous Players was going to buy Loew's Ottawa. It had just

purchased Loew's Montreal.

Negotiations ended when the B. F. Keith Company of Canada Limited,

newly incorporated with a reported capitalization of $5 million, took

over Loew's Ottawa in September 1924. The new company's headquarters

were in Montreal, and its president was Edward F. Albee of New York. The

corporation did its own financing, and no stock was to be issued to the

general public.

Five other theatres were purchased by the new company, the Princess

and Imperial in Montreal, Shea's Hippodrome in Toronto, the Lyric in

Hamilton, and the Majestic in London. An American source wrote that

these theatres previously constituted Canadian United Theatres, a chain

operated by Mike Shea and Joe Franklin. The Canadian Moving Picture

Digest merely reported "a number of Canadian interests are merged in

the new Keith undertaking."16

Though a new company had been formed, the Keith vaudeville circuit

was not a newcomer to Canada. In 1913 it had erected two deluxe

vaudeville theatres, the Imperial in Montreal and in Saint John, and

since at least 1906, Keith vaudeville acts had been booked into

affiliated Canadian houses by its subsidiary, United Booking Office.

Neither was Keith vaudeville new to Ottawa audiences in 1924. The

Franklin theatre, operated by J. M. Franklin, and Bennett's

(subsequently the Dominion) theatre had presented Keith acts. B. F.

Keith's was one of the oldest circuits, begun in 1893 when it opened one

of the first super deluxe vaudeville houses in Boston.

B. F. Keith initially provided the money and gave the circuit its

name. He died in 1914, long before the circuit had peaked. (In 1920 it

reportedly controlled more than 400 theatres.) Before and after Keith's

death, Edward F. Albee was the driving force of the circuit. It became

renowned for building palatial vaudeville theatres, for helping to

"clean up" vaudeville, and for instistituting the "continuous

show."17

Loew's Ottawa theatre was not in financial difficulty at the time of

the sale to Keith's. The fourth annual meeting of the board of directors

of the local holding company (Loew's Ottawa Theatres Limited) reported

that the theatre had earned $40,000 profit in 1923, compared to a small

deficit the year before.18 Following the sale, Loew's

holdings in Canada dwindled to two theatres in Toronto and one in

London. Famous Players Canadian Corporation had acquired Loew's theatres

in Hamilton and Windsor. Loew's disengagement was seemingly voluntary:

in April 1923 the company had proclaimed that it planned to dispose of

all its Canadian holdings in order to pursue expansion in the New

England states.19

Coincident with the B. F. Keith takeover in Ottawa came the

announcement from N. L. Nathanson that Famous Players was proceeding

with the construction of its Queen Street theatre. He added

significantly that Famous Players was the distributing arm of Paramount,

MGM, Pathe and other producing companies, and that his company was a

Canadian organization, 95 per cent of its stock being owned by 1,700

resident Canadians. The Canadian Moving Picture Digest retorted

in an article entitled "Famous Players Patriotic Line of Defense," "he

forgot to mention that Famous Players Canadian Corporation is a

subsidiary of the Famous Players Company."20

Famous Players Canadian had grown from strength to strength since its

incorporation. Sidney S. Cohen, chairman of the board of the Motion

Picture Theatre Owners of America, was so alarmed by the company's might

in 1924 that he felt constrained to issue

a needful warning to theatre owners to exercise eternal vigilance

against any such deplorable state of affairs as exists in our fair

neighbour to the north — Canada. One man there controls the

distributing rights to the product of every so-called "big company" in

addition to theatres in any number of key spots. The predicament of the

independent producers and distributors is fraught with

danger.21

Yet only five years before the Allens had owned the predominant

Canadian theatre chain (Fig. 119). Following the transfer of the

Paramount franchise, the Allens' fortunes had plummeted as those of

Famous Players Canadian soared. Only a year later, Jule Allen had to

deny a report that his circuit had capitulated. In 1922, the Allens were

in deep financial trouble. With an array of creditors at their heels,

they were forced into assignment. In February of that year an Allen

spokesman had confirmed that the sale of the circuit to Famous Players

Canadian had been approved by both boards of directors. The cost to

Famous Players of taking over about 50 Allen theatres was reputed to be

$5 million. Apparently the Famous Players Canadian offer was later

withdrawn "because of alleged changes in the Allen circuit." Further

extensive negotiations were embarked upon, during which First National

(an American concern) and "other interests" made offers for the

beleaguered circuit.22

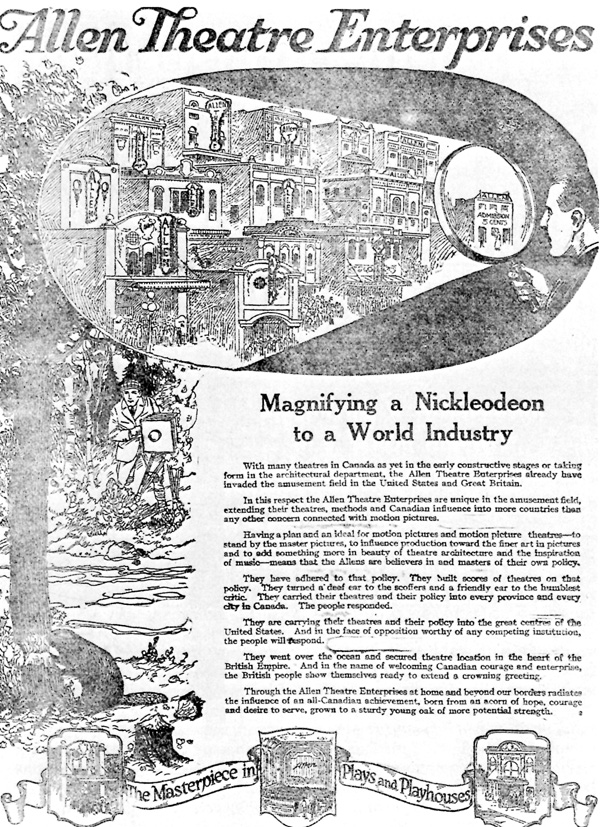

119 Before the fall: Allen Theatre Enterprises.

(Mail and Empire,

Toronto, 28 August 1920.)

|

By 1923 the surrender was complete. At the annual general meeting of

Famous Players Canadian in December, N. L. Nathanson related that the

company had paid $392,073 in cash and stocks for the assets of Allen

Theatres Limited to the company's receiver, thus gaining control of

about 20 theatres, and bringing the total number of theatres operated by

Famous Players Canadian and affiliated companies to 64, a number without

precedent for a theatre chain in Canada. In less than a year their

holdings had increased to 82.23

But the company remained unsatisfied with its lack of the largest

theatre in Ottawa. One month after the B. F. Keith takeover, it was

rumoured that Keith and Famous Players Canadian were combining to

operate a few houses for mutual interest, foreshadowing the combine of

1929. Nothing immediately came of this, nor of Famous Players' offer to

sell its Queen Street site. In July 1925 it purchased a large adjoining

property in order to accommodate "a huge picture

palace."24

New plans for this site were advertised every year until 1929. In

1926. it was to be occupied by a 12-storey building with a theatre "at

the rear." In 1927 the circuit was going to build a legitimate theatre

on the site, as Ottawa's only legitimate theatre, the Russell, had

closed. In 1928 Thomas Lamb was said to be in Ottawa planning a

$1,250,000 Capitol theatre. Many details were announced. It was to have

only one box — a royal one — reserved for visiting members of

the royal family and their Canadian representatives. Atlas construction

was building the theatre, which would be permanently equipped for sound

movies. Ray Tubman would manage it, and the opening was slated for

January 1929. The last theatre proposed (in March 1929) was going to

introduce to Ottawa an interior finished in "gorgeous Oriental style,"

it was to cost $750,000 and to accommodate 2,400 patrons.25

After the 1929 RKO-Famous Players agreement, the Queen street site was

finally sold. Famous Players Canadian had achieved its goal of owning

the biggest theatre in Ottawa.

About two months before on 7 March 1929, the public was informed that

control of Famous Players Canadian had passed into Canadian hands,

fulfilling N. L. Nathanson's longterm ambition. American shareholders

were bought out although the Paramount franchise was

retained.26 Adolph Zukor could not be counted out of the

company's dealings. Though he relinquished his position as president, to

"protect" the contract between Paramount and Famous Players, he became a

member of a newly formed three-man voting trust. He could be outvoted by

the other two members, N. L. Nathanson and I. W. Killam, the latter the

principal stockholder in Famous Players Canadian.27 Though

Zukor could have retaliated by withdrawing the lucrative Paramount

franchise from the Canadian company if he had been frequently outvoted,

it was also to his advantage to maintain the contract with a chain in

Canada which, in 1930, had a near monopoly on first-run exhibition, was

afforded a substantial proportion of all revenues from theatre

admissions and controlled 207 of 299 chain theatres.28

The corporation's publicity at the time of the voting trust agreement

stressed that the company had grown steadily more Canadian as it

expanded, so much so that a week before the agreement, "the only

Broadway factors left in this large, many-millioned growth of a few

years were two words of a name, the rentals paid for films, and the

dividends to a minority of shareholders."29 No records

listing the various shareholders in the company could be found for this

period. It is doubtful, however, that Zukor's hold on the company was as

tenuous as that described in the previous paragraph. Though Zukor

maintained effective voting control before 1929, apparently Nathanson

was allowed considerable latitude in directing company

policy.30

In the fall of 1929, Nathanson was brought down by the marshalled

forces of Adolph Zukor, I. W. Killam and several of his fellow

directors. They rejected his plan for an alliance with the British

Gaumont company for the stated reason that it was controlled by the

American Fox concern. In all accounts, Killam took at this time an

especially firm and patriotic stand against the scheme. Outvoted by the

voting trust who refused to place the offer before the shareholders,

Nathanson resigned as managing director, his position being assumed by

Arthur Cohen.31

Less than a year later, in August 1930, the voting trust and a

majority of the company's directors and shareholders agreed to Paramount

Publix' offer to exchange five shares in the Canadian company for four

of its own. After the exchange, J. P. Bickell assured the shareholders

that the affairs of the company would be carried on "under the same

policy and the same progressive manner" as before, and the returns from

dividends would be higher because of "the underlying assets of the

larger company with its diversity of operation."32 Paramount

Publix assumed complete control, securing 93.786 per cent of the total

issued shares. In about 1953, Paramount trimmed its holdings to 51 per

cent. These shares were taken over in 1967 by Gulf and Western

Corporation. The Canadian Film and TV Weekly attested in 1969

that Canadian investors had lost two opportunities in the last decade

alone to gain control of Canada's biggest theatre-owning

company.33 Famous Players Limited now controls over 400

theatres, including the few remaining movie palaces.

|

|

|

|