|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 13

All that Glitters: A Memorial to Ottawa's Capitol Theatre and its Predecessors

by Hilary Russell

Building a Movie Palace: The Capitol

A movie palace was an extremely complex structure to design and

build. To be successful it usually required the collaboration of an

architect, a structural engineer, and electrical engineer, a heating

and ventilating expert, an acoustics consultant and an interior

decorator.1 It was these experts' job to produce a building

that was comfortable and well ventilated, had exemplary sight lines

and acoustics, with enough circulation space and exits for thousands of

patrons, and the appearance of being unstintingly luxurious. Yet, in

most cases, a movie palace had to be built and opened in the shortest

possible time so that its owners could begin to recoup their

investment.

Some of the grandest movie palaces took between one and two years to

build, equip and decorate. Usually, their opening dates were predicted

months ahead of their actual openings.

It is not...[an overstatement] to describe cinema building

operations as an unceasing headlong rush from the time the boarding

surrounds the vacant site to the moment when the last painter and

chair-fixer are being "shushed" out of the back door whilst the mayor

and corporation are crossing the red carpet...to the front door to the

opening ceremony.2

At Loew's (Ottawa) opening, representatives from Government House and

City Council encountered a lobby hung with Canadian flags, bought at

the last minute to disguise unfinished plasterwork.3

The Ottawa Citizen announced on 24 July 1919 that Bate McMahon

Company would begin to construct the following week a Loew's theatre on

the corner of Bank and Queen streets.4 Its cost was estimated

at $500,000 and the theatre's opening was predicted for the following

January.

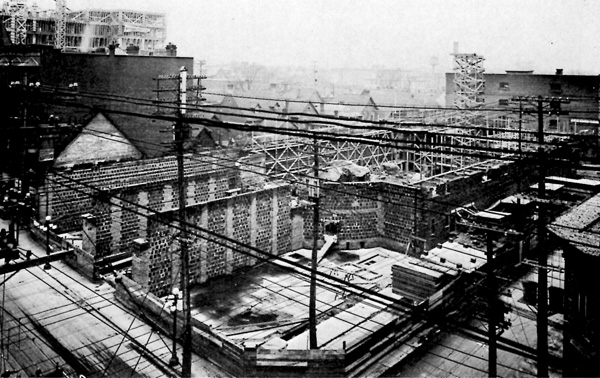

To make way for a building that extended 99 feet along Bank Street

and 264 feet along Queen, a number of one-storey brick and brick veneer

offices and commercial establishments (all except one fronting on Bank

Street), a livery stable and a few iron sheds were demolished. A

considerable portion of the lot was empty on Queen Street. In their

place rose a four-storey movie palace of brick over a steel frame or

"composite construction" (Figs. 66-67).

66, 67 Loew's (Ottawa) theatre under construction in 1919. The gentleman

with the moustache and spats in Figure 67 resembles Thomas Lamb.

(Photograph courtesy of Miss Helen Ewart.)

|

Steel frame construction, though relatively expensive and new, had

many advantages. It allowed a greater speed of erection than reinforced

concrete in situ construction or the building of load-carrying

brick walls of statutory thickness. It produced an initially drier

building which could be plastered and painted sooner than a reinforced

concrete structure. "In auditorium construction the cavities resulting

after stanchion casing between the outer wall and the inner flush skin

[could] be used for upcast ducts in connection with the ventilating

system."5 As well, "in being able to span reasonable distances,

steel frame construction offered an easy solution to the problem of

creating stage areas and proscenium openings." Finally, it produced more

floor space than buildings with thick load-carrying brick

walls.6

The outer and inner brick walls of the theatre were constructed

simultaneously. The space developed between them, the cavity wall,

accommodated the ties which joined the two structures and provided

insulation. Air space and cinders between the poured concrete floor (at

ground level) and the interior hardwood flooring afforded additional

insulation.

The movie palace architect and engineer were faced with the problem

of constructing balconies that seated more than a thousand, projected 50

to 100 feet, rose at an angle of 20 to 30 degrees, spanned wide spaces,

had a depth of two or even three storeys, yet were free from severe

vibration when the theatre was being filled and emptied.7

Great cantilevered balconies were the solution; in addition, they

obviated the need for view-obstructing columns in the auditorium.

"Immense loads could be transferred to the wall stanchions using a

minimum of material" through a criss-cross-cantilevered system of

steel structural members and girders.8

A greatly simplified explanation follows of the construction method

employed for the 1,077-seat balcony of the Capitol and the rest of the

movie palaces:

Usually, such a balcony is fed at two or more levels through its

thickness in the manner of the seats of an amphitheatre, and the large

spaces left are utilized as retiring rooms, smoking rooms, and lounges

generally....These great balconies are only partially built on the

cantilever principle. A great lattice girder 10 or 12 feet deep is first

placed at the nearest point to the front of the balcony which will

provide sufficient depth. The cross beams are then placed running as

cantilevers to the front edge. Through the spaces of this great lattice

girder the tunnels feeding the seats have sufficient headroom to

pass.9

It was not the case, as one observer complained, that the movie

palace dome, "a feature that needs a maximum of support," was "gaily

dragged in and suspended from heaven by goodness knows what

means."10 The flat roof of the theatre, comprising fabricated

steel trusses supporting steel I-beams, joists and boards, and a coat of

tar and gravel, supported the metal lath and plaster-suspended domes of

the Capitol's grand foyer and auditorium. Angle irons were knitted into

the metal lath network, which was shaped into a dome and suspended from

the steel decking of the roof by a myriad of steel hangers or

trusses.

The metal lath network provided an ideal key for a minimum quantity

of fibrous plaster which was applied from the under side of the dome.

The plaster was smoothed and shaped on application with hand-held wooden

or metal "running moulds," whose templates were cut to resemble a

reversed cross section of the form they reproduced. The plaster dome

might be "run" as many as ten times, and between each application, the

plaster was allowed to set. Finally, 1/32 inch of plaster of paris, or

the "white coat" was skimmed over the fibrous plaster.

The basic form of the dome was defined in this way. Cast plaster

enrichments were applied later, or, if they were heavy, were attached

directly to the metal lath with fibres and plaster (Figs.

68-69).11

68, 69 The dome of Pantages theatre (Toronto) under construction in

1920. 68 The framework for the metal lath and the tree hangers

are clearly visible. 69, After plastering the hole in the centre

accommodated the cable of the chandelier, which was attached to a winch

whose platform was supported by she steel of the roof. The gaps in the

plasterwork at the top of the photograph served as the "air return."

(Micklethwaite photos.)

|

This dome construction was common in movie palaces and was

structurally sound. The dome would not be jeopardized by the breaking of

one or several of the steel hangers. But the dome could be damaged by

the impact of a body falling off the catwalk that usually encircled the

dome under the roof. It is possible that such a body might fall right

through the dome, but its metal lath probably did not very easily

rupture, and no instance was discovered of someone taking that route

into the auditorium or grand foyer (Figs. 70-72).

70, 71, 72 Details of roof and dome construction in the Ottawa Capitol.

The area between the rim of the dome and the roof accommodated catwalks

and ventilating ducts. In Figure 65 (Montreal Capitol dome), a board

covers an area damaged when someone missed his footing on the catwalk.

The victim was rescued, and did not end up among the balcony seats.

|

After the roof and the shell of the building were fairly well

completed, it was the job of the ornamental plasterers, painters,

decorators and other subcontractors to make the structure into a movie

palace under the architect's guidance (Figs. 73-74).

73, 74 Two of the architect's plans with

instructions on decoration. 73, Plan of auditorium and grand

foyer ceilings. 74, Cross-section, grand foyer, auditorium and

stage.

(Famous Players Limited.)

|

Miss Ann Dornin of Thomas Lamb's office in New York supervised the

work of G. T. Green Ltd., the local firm responsible for exterior and

interior painting, the ornamental plastering firm of Peter B. Baxter of

Montreal, and William Eckhardt of New York, who was responsible for the

decorative paintings and murals. Mm. J. A. Ewart was the local

supervising architect.

It does not appear that "interior decorations were sent up boxed from

the United States, each piece numbered, to be erected according to

instructions."12 The duty and shipping costs involved in such

a system would have been prohibitive. As well, it was Lamb's custom to

employ local craftsmen and materials when available.13 He

maintained an office in Toronto where the plans for his Canadian

theatres were drawn up.

The blueprints for Loew's Ottawa theatre, which included

specifications for the plaster decoration required, were submitted to

Baxter's plastering firm. Novel designs were modelled in clay to

specifications and plaster casts produced. The firm no doubt maintained

plaster moulds of most of the fairly commonplace mouldings and motifs

employed.14 From these flexible gelatine moulds were

made15 from which numerous castings would be duplicated.

Gelatine moulds were best suited to work requiring much repetition

without excessive cost. They also reproduced undercut relief modelling,

and, perhaps best of all, could be melted down and

remoulded.16 Cast plaster panels were obviously delivered to

Toronto's Pantages theatre (see Fig. 69), and it is possible that

Baxter's firm may have shipped tons of breakable ornamentation from

Montreal. But often a plastering firm working out of town set up a small

shop on the site or rented one a short distance a way.

Fairly small ornaments were cast in fibrous or solid plaster in one

piece. Sometimes they were additionally backed with cheesecloth, burlap

or some other reinforcement. They were fastened to a plastered wall or

ceiling with moist plaster, which was blended with a small wet brush.

Running ornaments and mouldings were cast in sections, perhaps two or

three feet long, and fixed in the same way. Breaks and joints between

the castings were smoothed (or "jointed") with plaster. Large sections

of ornament were cast in fibrous plaster as this material, reinforced

with hemp fibre, was light (less than one quarter the weight of solid

plaster), tough and quickly dried. These large sections were nailed or

screwed in place, or affixed with fibre and plaster (Figs.

75-76).17

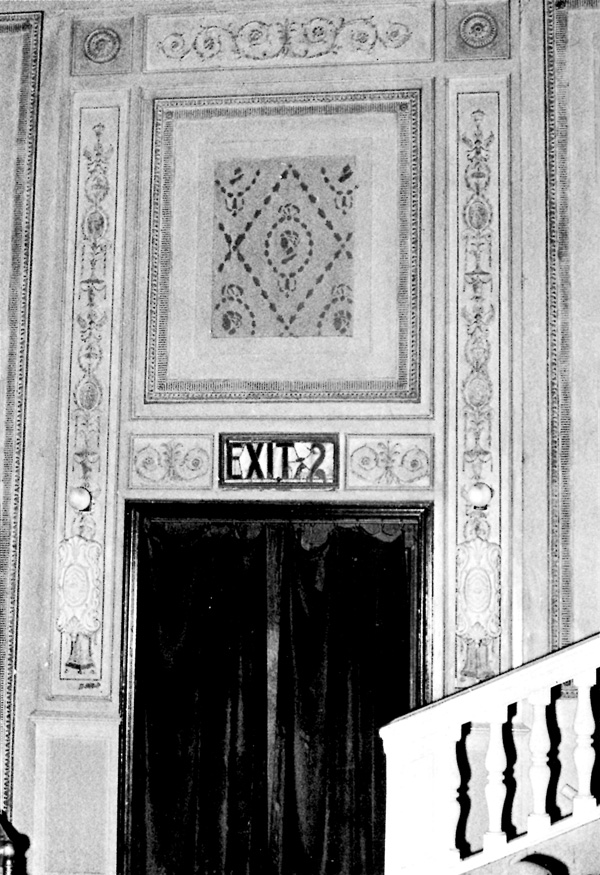

75, 76 Examples of the Capitol's low relief plaster decoration —

running ornament cast in identical sections, and individual ornament

cast in one piece. 75, Decoration around the rim of the

auditorium dome. 76, Adam arabesques and plaster medallion over

the doorways in sine grand foyer mezzanine.

|

Cornices were cast in fibrous plaster as hollow shells and reinforced

with pencil rods, or were run "on the bench" (not in situ). The

template of the running mould was cut to leave beds in which mouldings

and enrichments, cast in sections, were embedded.

Large free-standing features were produced in piece moulds and were

fitted and stuck together. Certain of these features were left hollow if

they had no supporting function. But each baluster which, like a plain

column, was cast from two identical moulds, was filled with plaster and

was supported by a steel rod in the centre. Supporting columns probably

had a core of masonry, structural steel, wire lath and plaster mixed

with coarser mortar, and were "cased" with two vertical plaster

casts.18

Plaster ornament was the cheapest expensive-looking decoration

available.19 Plaster was also used as a cheap substitute for

marble. The columns in the auditorium, lobby and grand foyer, and the

balustrade of the main staircase were scagliola, a rock-hard plaster

composition which closely resembled marble (Fig. 77).

77 Plaster friezes and free-standing and engaged

columns in the sidewall arches of the auditorium.

The column and the pillar with the quasi-Ionic

capitals are "scagliola."

|

Mr. Fred Balmer, whose plastering firm decorated Loew's Uptown in

Toronto, described the production of a scagliola column. It required

considerable expertise. A two-foot strip of stretched oilcloth large

enough to go around the plaster column was laid down, and veining colour

applied by swirling on the surface a bunch of silk threads knotted at

one end and dipped in pigments of suitable marble colour like sienna. On

top of this, Keen's cement, a very fine plaster fortified with cement,

was gently applied until it was a quarter of an inch thick. The ensemble

was then wrapped around the column, and the oilcloth removed at a safe

time. When the whole column had been treated and was dry, it was rubbed

down with a pumice stone, followed by another fine stone, and then

polished and oiled to give it a gleaming marble-like

appearance.20

The steps of the main staircase were marble. They were reportedly

shipped to the site numbered in order.21 Other areas subject

to excessive wear and team, like floor trim, wall bases and radiator

covers, were faced with marble.

The final movie palace touches were made with paint. Two-dimensional

designs and specifications for the colours used throughout the theatre

were laid down by William Eckhard's firm, which was wholly responsible

for the free-hand art work. G. T. Green's firm did the rest of the

painting, including any stencilling that decorated the theatre in 1920.

Mr. Green does not think that much stencilling was done in the theatre

at that time, but conceded that in the 1920s stencilling was a popular

method of decorating large public buildings and even private

homes.22 The earliest photographs available of the theatre's

interior reveal that many of its wall areas were stencilled.

Stencilling, like plaster ornament, was inexpensive. The stencil work

seen in the Ottawa Capitol was relatively uncomplicated as it involved

only two colours (Fig. 78).

78 A stencilled wall panel in the Capitol's auditorium, 1970.

|

Plasterwork was not painted in the same way as woodwork. G. T. Green

was instructed to apply three coats of white lead mixed with linseed

oil, turpentine and japan drier to "green" and even wet plaster. This

step was to be followed by an application of ground colours and raw

linseed oil. (Usually plasterwork had to be aged and its suction allayed

before it was painted. It could be aged artificially by applying a

solution of zinc sulphate.23) The procedure employed in the

Capitol was completely new to Mr. Green and seemed reckless. He was told

that it was followed in all American movie palaces. He waited in vain

for the plaster to fall off.

The Capitol and other movie palaces looked much more expensive than

they really were. Most of them in Canada cost less than $1 million, often

including the cost of the site. The building type could be

characterized as "architecture of illusion," and it was thoroughly appropriate

that illusionistic edifices were built for motion pictures.

The method and spirit of movie palace architecture were very close

to those of the movies themselves. Poplars and palanquins, palm trees

and pergolas were imitated in lath and plaster as they would be on a

film set.24

Many of the Capitol's former patrons would be surprised to learn

that they had once gasped at wire lath and plaster domes, and wooden and

scagliola columns and balustrades.

|