|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 13

All that Glitters: A Memorial to Ottawa's Capitol Theatre and its Predecessors

by Hilary Russell

In the Beginning

To understand the Capitol and theatres like it, the movie palace

phenomenon must first be examined in its historical perspective. The

evolution of the movie house is a romantic story in the great American

"rags to riches" tradition. Until 1902 there was no such thing as a

movie theatre in a permanent location, though motion pictures as a

commercial medium were then eight years old. During these years they

were generally exhibited in penny arcades and fairground tents, and also

were crowded into vaudeville theatre programmes. After 1902 they found

exclusive and more or less permanent homes in small, stuffy converted

stores with rudimentary furnishings, characterized by many as "firetraps

and pestholes [which up set] the social balance and public

morals."1 A little over a decade after the appearance of the

primitive store theatre, movies had become the feature attraction in

colossal, sumptuous edifices too splendid to be called theatres.

Motion pictures were initially displayed in a viewing apparatus about

the size of a filing cabinet. This device, often credited to Thomas A.

Edison and called a "Kinetoscope," was essentially a coin-operated

peepbox in which one viewer could watch for a minute or less through a

slightly magnifying lens an illuminated cylinder of about 50 feet of

celluloid film revolving on spools. These machines were first

commercially exhibited in North America on 14 April 1894 at 1155

Broadway, New York, by Andrew and George C. Holland of Ottawa. Soon

afterward, Kinetoscopes appeared in "Edison parlours" (small stores

which also offered Edison phonographs), in curio shops and as fairground

novelties (Figs. 1-3).2

1 The forerunner of the movie house, a Kinetoscope parlour, around

1897-98, 946 Market Street, San Francisco.

(National Film Board:

photo credited to Peter Bacigalupi.)

|

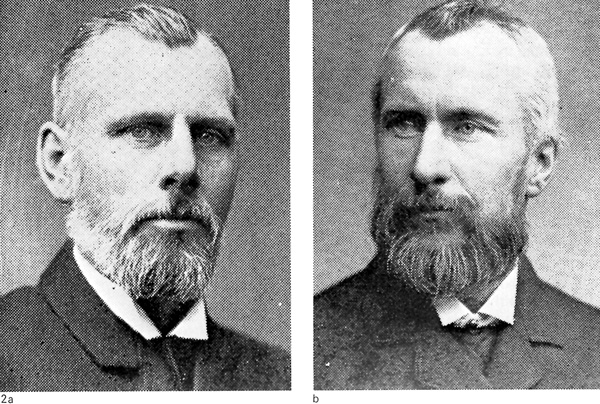

2 The first public exhibitors of Edison's Kinetoscope, Ottawa's Holland

Brothers, Andrew M. (left) and George.

(Canadian Film Institute.)

|

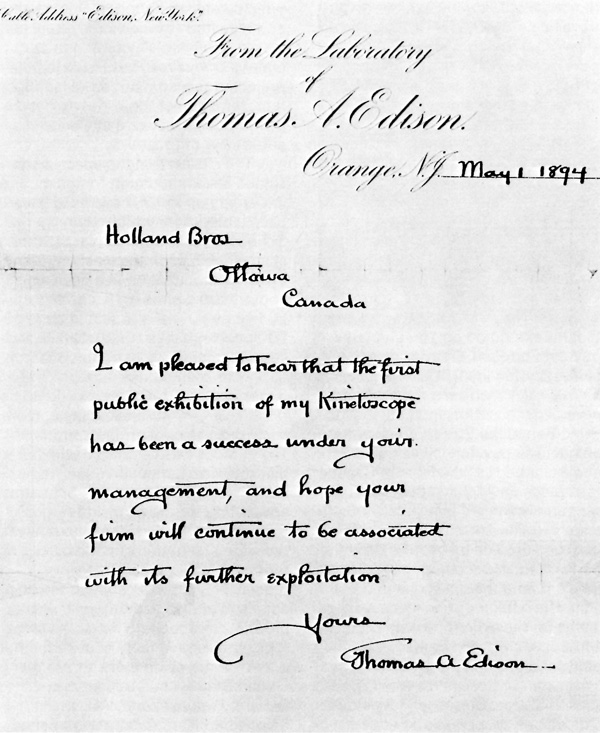

3 Edison's letter to the Holland Brothers acknowledging their pioneering

achievement. The exhibition referred to took piece in New York City on

14 April 1894.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

On 23 April 1896 motion pictures were screened to a paying audience

in a vaudeville theatre, Koster and Bial's Music Hall, Herald Square,

New York. "Thomas Edison's Latest Marvel, The Vitascope" shared the

billing with six vaudeville acts (Fig. 4). The Vitascope was a screen

projector developed by Thomas Armat, though acquired and sponsored by

Edison, and was based on the principles of the Kinetoscope. Motion

pictures became "life sized," and were revealed to the Koster and Bial

audience on a "gold framed screen," but the Vitascope movies, though of

increased footage, remained very similar in content to those seen

through a Kinetoscope peephole.3

4 Koster and Bial's programme, April 1899. As in Kinetoscope days,

little bits of scenery or action are featured.

(Ben Hall Collection,

Theatre Historical Society.)

|

After their commercial screen debut, motion pictures continued to be

shown in vaudeville theatres as one of many attractions on the bill.

Little expenditure was required to introduce moving pictures to a

vaudeville programme.

A simple screen was erected, often of plain muslin on a wooden or

iron frame, and an area sealed off for projection equipment. When the

stage was in use...the screen was lifted into the fly tower or carefully

rolled and stored at the back behind the flats.4

Motion pictures were associated with vaudeville for about 30 years in

the United States and Canada. Initially, the novelty of seeing

life-sized moving pictures was popular with vaudeville patrons. But

early moving pictures were short (100 to 1,000 feet in length), often

flickering and hard on the eyes (mostly because of imperfect

projection), and usually were devoid of narrative interest. Such

subjects as a moving train, sea waves, or various vaudeville acts were

filmed. By the turn of the century, moving pictures had lost their

novelty value, and were offered in vaudeville houses merely as "chasers"

to indicate that a new show was approaching and the house should be

cleared.5

By about 1914, with the introduction of feature-length movies, the

star system and a permanent industry in Hollywood, motion pictures had

come a long way from being a poor relation as a commercial medium and

had eclipsed their former master, vaudeville, in content, scope and

commercial appeal. Throughout the 1920s theatres continued to be built

with stage facilities as vaudeville was still popular, though seldom the

feature attraction, and theatres with a straight vaudeville policy had

become virtually a thing of the past. Furthermore, stage performances

tended to endow a theatre that showed movies with a certain

respectability.6 The humble and even disreputable beginnings

of motion picture exhibition had not been forgotten.

Between 1896 and 1902, besides being shown in vaudeville theatres,

moving pictures were exhibited by travelling showmen (mostly in the

summer in Canada) in community halls, empty stores rented for a week or

two, on vacant lots covered with tarpaulin, and at amusement parks,

circuses and fairs.

Although in accounts of Canadian film history, Toronto, Ottawa and

Montreal vie for the distinction of being the first Canadian city in

which travelling showmen projected moving pictures. Ottawa may have the

edge in the contest.7 John C. Green, a magician by trade,

early and frequently insisted in Moving Picture World and in the

Canadian Moving Picture Digest that his exhibition on 15 June

1896 in West End Park, Ottawa, was the earliest in Canada. His date

appears to be five weeks too early; contemporary newspaper accounts

indicate that an exhibition of the Edison Vitascope at an open-air

pavilion in West End Park and described as "the first...in Canada" took

place on 21 July 1896.8 This description is entirely

plausible, as Ottawa's Holland brothers, who had introduced the

Kinetoscope in the United States, had also secured "the sole right for

exhibiting the Vitascope in Canada." The Hollands had made arrangements

for the exhibition with O'Hearn and Soper's Electric Railway Company,

and this company had engaged a magician (whose name was variously

spelled Belzac, Belsac, and Belsaz in Ottawa newspapers) as an added

attraction. (Green no doubt was "Belzac," and used a more exotic name

than his own.) In his reminiscences, he recalled that he had contributed

a 30-minute magic show and had described four Edison 50-foot films which

were strung together in a belt and repeated as long as the projector was

in operation. According to an Ottawa Daily Free Press reporter,

the projected scenes included "a laughable representation of the widow's

kiss," a whirlpool, the waves at Coney Island and a view of Broadway.

The closest thing to specially designed accommodation for the movies

in Canada up to 1902 seems to have been a black tent which John A.

Schuberg (alias Johnny Nash), a travelling showman in the western

provinces, averred that he had devised about 1900. Schuberg's tent

measured 20 feet by 60 feet and seated about 200 people. It was made of

black canvas with an inner tent of black canton flannel to keep out the

sunlight when it was windy. The "sidewall" could be raised every 20

minutes at the end of each show to cool off the patrons. The exterior

was decorated with a marquee-like banner on poles, together with fairly

lurid paintings or posters advertising the movie inside (Fig.

5).9 Schuberg conceded, "I may not have been the first to

think up the black tent, but I had not heard of any

others."10 Such modesty was uncharacteristic of early

exhibitors. It was appropriate in Schuberg's case. as black tops had

become fairly popular by that date with travelling exhibitors in the

United States. In a 1916 article in Moving Picture World, William

H. Swanson related that he had opened "the very first black top tent

that was ever put up" in Booneville, Indiana, in July, 1897. His tent

was of dyed black canvas and was lined with black cotton cloth. His

exhibition was interrupted when a rain storm washed all the dye out of

the canvas, but a tent-maker subsequently produced for him a permanently

black tent. Swanson later contrived a red canvas tent lined with black

cloth with "properly protected ventilators in the 'top'" — he had

noticed that a great number of his black-top patrons were regularly

overcome by the summer afternoon heat. If it is true, Swanson's account

of the entertainments offered in his "Red Dome" perhaps vaguely

foreshadowed later movie palace extravaganzas.

The exhibition...consisted of 2,000 feet of motion pictures, the

singing of the "Holy City" by an illustrated song singer, poses

plastique, fire and serpentine dancing staged with proper electrical

effects, electric glass water fountains on each side of the stage, a

spray of water from the proscenium arch on which stereopticon slides

were projected, silk rags with electric fans underneath and gelatine red

effects thrown on them while they were blown in the air from the stage

floor.11

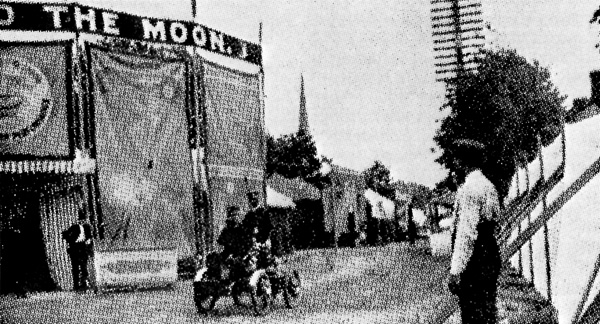

5 John A. Schuberg's tent theatre at a 1900 street fair. This was the

earliest type of structure especially designed for moving picture

exhibition.

(Canadian Film Digest; photo courtesy of National Film

Board.)

|

Between 1903 and 1905 another type of structure emerged which was

specifically adapted to motion pictures. George C. Hale of Kansas City

built for the St. Louis Exposition an imitation Pullman car in which

moving pictures taken from moving trains were projected. The attraction

was billed as "Hale's Tours and Scenes of the World." The entrance to

the "theatre" was fashioned to resemble the observation platform of a

caboose, and the ticket collector was sometimes dressed as a train

conductor. About 70 patrons, ensconced in regulation coach seats, could

watch life-sized tracks seemingly disappearing under the coach and

spectacular scenery flashing by on a screen or sheet at the "forward

end." Special effects heightened the illusion; these were provided by

"an elaborate equipment of levers, pulleys, wheels, and sound-making

devices."12 In addition, the structure was frequently joggled

either mechanically or by an attendant outside. Thus, the patron not

only heard the locomotive whistle, the wind rushing by and the brakes

being applied, but he was jolted and tipped from side to side as the

"train" rounded a curve or gathered speed. Motion pictures had yet to

find a home in a solid, permanent structure. Many exhibitors adopted

Hale's device; imitation trains proliferated as an amusement park

attraction. As well, they appeared in Vancouver, Winnipeg and Toronto by

about 1905;13 but the novelty of the exhibition soon wore

off, a contributing factor being that exhibitors were hard-pressed to

change their programmes often enough to attract new patronage, in spite

of the fact that films were being produced expressly for Hale's

Tours.

Until about 1905-06 such shortages of films generally obliged

exhibitors to keep moving. They usually bought a limited quantity of

films from producing companies and exhibited in as many locations as it

took for their prints to wear out. Permanent movie theatres were not

established in quantity until there was sufficient film available for

rent to exhibitors from film exchanges to allow for regular changes of

programme on one site, and until the advent of the story picture. When

these conditions were met, the general standard of motion picture

exhibition took no great leaps forward. Between about 1905 and 1907,

more or less permanent cinemas were established in small converted

stores, dance halls and converted penny arcades. Though these were their

habitual locations, they could also be found in skating rinks,

deconsecrated churches, or in virtually any building (preferably on a

main street) that was available at a reasonable rental (Figs. 6, 7).

6, 7 Two Canadian "converts." 6, A converted barn in Dundas,

Ontario, ca. 1909. (Archives of Ontario.) 7, The Dreamland in

Edmonton about 1910.

(B. Brown Collection, Archives of Alberta.)

|

To convert a small commercial establishment into a movie theatre,

enterprising exhibitors replaced the store fronts with a set of doors

and a small wooden box office set back from the sidewalk, thus creating

a tiny, wind swept "lobby" which was decorated with florid movie

lithographs. The strident music and announcements of a phonograph and a

barker in this area were additional enticements. Usually, the theatre's

name was inscribed on either a large canvas, wooden or electric sign

over the entrance doors.14 Some of these premises were

perhaps 25 feet wide and 100 feet long and, as auditoriums were narrow,

dark, and ill-ventilated. They seated as many as the room would hold,

either on unfastened "kitchen" chairs, wooden benches nailed together in

rows, or on folding chairs rented by the day from undertaking or

catering establishments. (In the latter case, patrons were forced to

stand when the owners reclaimed their chairs.)15

When there was a full house, the auditorium was oppressively hot; a

1907 store show exhibitor recalled that "there was an average of two

women fainting every Saturday night, and they were wedged in so tight

they couldn't fall."16 On such nights, the air in the

auditorium quickly became stale and sour. Some measure of relief was

afforded by thoughtful exhibitors who installed small wall fans (which

mostly churned up stale air) or who occasionally left a door open. From

time to time, vain attempts were made to deodorize the auditorium by

aiming a garden sprayer filled with cheap scent over the heads of the

assembly.17

It was widely assumed that the best picture was projected in the

darkest auditorium, thus any windows were covered with black cloth (or

even paper), and interior decorations were, in most cases. non-existent

or minimal.18 Often the projector was merely roped off in the

middle or at the back of the room. If a cloth-covered projection booth

was provided, it was usually barely large enough for one projector and

the operator, and he could not move about without agitating the "walls"

of the booth. Like many of his colleagues, the operator in the tin-lined

booth at the Vitascope on Mount Royal East in Montreal could not stand

upright.19 The projectors were hand-cranked, and were

equipped with a stereopticon attachment, frequently used to project a

slide asking for "One Moment Please."20 The film fed through

the projector accumulated in a heap either in a galvanized iron tank or,

in the "cheaper" houses, in a barrel, cloth bag, or a basket on the

floor. When the film broke, the operator was obliged to paw around in

the tangle of film to find the right end. He was not always successful,

an early exhibitor remembered, and "when the reel was run off the next

time, the last part would come first, then the next part would probably

be upside-down, and the end came in the middle of the

picture."21

A painted or plastered wall, a bed sheet or a large canvas served as

the screen. In front of it, a "classy" store theatre had a small stage

or platform used by the lecturer who interpreted the movies and by

singers of "illustrated songs." Illustrated songs were a variety show

invention, but they usefully filled the interval between reels in a

movie house. The ballad singer (or singers) was accompanied by a pianist

(installed on or near the "stage") and by a series of stereoptcon slides

appropriate to the mood and story of the song.22 (The editor

of Moving Picture World once unkindly suggested that the singers

worked with slides so that the darkness would spoil the aims of

projectile throwers in the audience.)

The pianist (who was sometimes also the ballad singer) played an

accompaniment for the movie. but in many cases this was simply whatever

he felt like playing or knew by heart. A few houses in 1908 had a

three-piece orchestra consisting of a pianist, a violinist and a

drummer. If the members were in a playful mood, they might race each

other, and "the heroine could die to the tune of 'Turkey in the Straw'

played four times the usual speed for all the orchestra

cared."23

The programme was changed every 15 to 30 minutes, and the patron was

charged five cents though theatres with elaborate illustrated song

presentations often levied a dime (Fig. 8). These five-cent theatres,

considered the province of the poor and uneducated, swarmed across the

continent after 1905 and were largely concentrated in poorer shopping

districts and slum areas. They were disdained, apparently, as dens of

vice by large sections of the population.24 According to

Adolph Zukor, his first theatre, "The Comedy," was "not an exclusive

theatre. In fact, the ushers carried blackjacks."25

8 Nickelodeon Recollections, published in Moving Picture World,

vol. 37 (10 August 1918), p. 83.

|

Store theatres, or, as they came to be called, nickelodeons, are

usually discussed in secondary works on the film industry as forerunners

of the movie palace. They have received this attention partly because

the phenomenon was fairly short-lived and widespread, and partly because

of their jarring contrast to the movie palaces built only ten years

later.26 Yet there appears to be comparatively little

published research on the genesis and evolution of the vaudeville house,

which movie palaces more closely resembled.27 Like the

palaces, vaudeville houses followed the basic design of the legitimate

theatre with balconies, orchestra, boxes and stage. Though they paled

beside the opulence of the great movie palaces, many vaudeville houses

were pretentiously appointed.

The Keith-Albee circuit is reported to have built... the finest

theatres in the world for vaudeville. Beautiful lobbies with oil

paintings that cost thousands of dollars, rugs that cost more thousands,

dressing rooms that compared to the finest hotel suites.... They were

cathedrals.28

But even the earliest movie theatres aspired to middle-class

acceptance and money. One of the earliest, if not (as is often claimed)

the first regular commercial cinema, opened at 262 South Main Street in

Los Angeles in April 1902, was advertised by its owner, Thomas L. Tally,

as "The Electric Theatre. For Up-to-date High Class Entertainment.

Especially for Ladies and Children" (Fig. 9).

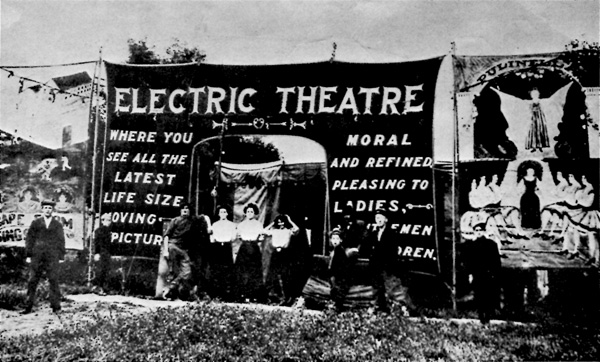

9 This photograph is often identified as Thomas Tally's 1902 Electric

Theatre in Los Angeles. It appears to be a canvas-fronted fairground

show.

(Canadian Film Institute.)

|

In October of the same year Canada's first lasting movie house, the

"Edison Electric Theatre," was opened by John A. Schuberg at 38 Cordova

Street, Vancouver. One of its printed programmes for February 1903

announced that an usher was in attendance to see that the ladies

obtained desirable seats.29

As a travelling showman, Schuberg had exhibited movies for two weeks

in 1898 on Cordova Street. He recounted that he had "rented a fairly

large, empty warehouse..., set up the equipment near the front and hung

the screen at the back. As the show could only run about 30 minutes,

seats were not necessary." But Schuberg provided no comparable

description of his 1902 Edison Electric beyond the biographical comment

that he opened "a similar house" in 1903 in Winnipeg in a high-ceilinged

storeroom.30

Tally's Electric Theatre offered movies as the exclusive

entertainment, while Schuberg's Edison Electric supplemented the

programme with vaudeville acts. Though the absence of film exchanges and

the scarcity of films must have precluded frequent and regular changes

of programme, both enterprises were quite successful and their owners

opened other theatres.31

The astonishing commercial success of John Harris and Harry Davis'

"Nickelodeon" opened in Pittsburgh in June 1905 was the real impetus

behind a flood of store-theatre openings. This theatre does not seem to

have initiated an exclusive motion picture programme on a permanent

basis as it is sometimes maintained. Probably, it became the most famous

of the early movie theatres because it made a great deal more money than

its predecessors.32 The owners were among the first to infuse

the showmanship into their store theatre enterprise which was eventually

to lead the industry to construct movie palaces. They adopted the name

"Nickelodeon" for their establishment, a combination of its admission

price and the Greek word for theatre. A projector, a phonograph and a

white sheet were installed in an empty store, and the auditorium was

dressed up with theatre chairs from the local Grand Opera House. Harris

and Davis also introduced alot of stucco, burlap, paint and incandescent

lights as well as piano accompaniment to the silent

drama.33

The success of this theatre coincided with the establishment of film

exchanges, and in 1906 so many store theatres opened that in October of

that year The Billboard of New York reported,

"No one is in a position to estimate the number of these exhibits

which are now in operation, for an estimate today would be worthless

tomorrow. In all big cities they seem to be on every business

block."34

This was also a significant year for Canadian exhibition. The first

lasting exclusive moving picture theatre in Toronto, "The Theatorium,"

was opened by John Griffin in March, 1906 on Yonge Street near Queen,

near the site of the present Yonge Theatre (Fig. 10). Griffin described

the Theatorium as

"not much more than a hole in the wall, for it was only seventeen

feet wide and a hundred feet deep. But it was a first-class site. That's

where people were passing up and down."35

Moving pictures and variety acts were offered for five cents. Griffin

noticed that his admission price seemed too low; many people were

ashamed to be seen going in. He raised the price to ten cents and so

prospered that, together with his son Peter he eventually operated the

Majestic, a legitimate theatre converted to vaudeville and movies, and

eight store theatres in Toronto as well as a number of combination

(vaudeville and movie) theatres and store shows in other Ontario centres

including Hamilton, St. Catharines, Sarnia, Chatham, Woodstock, Thorold,

Welland, Kingston, and Brockville.36

10 Toronto's first permanent movie house, John

Griffin's store theatre on Yonge Street. Originally called Theatorium,

its name was changed to The Red Mill by the time this photograph was

taken.

(Canadian Film Digest; photo courtesy of

Theatre Department, Metropolitan Toronto Central Library.)

|

The Theatorium was a marked contrast to Toronto's deluxe vaudeville

house, Shea's Yonge Street, built in 1899. According to a contemporary

newspaper account, Shea's lobby was beautiful, its walls tiled in white

with large oval mirrors in each panel, surrounded by wreaths in rose and

green tile. The reviewer was particularly impressed with the asbestos

drop curtain, "the Chief thing of beauty," on which was a painting, "The

Rising of the Mists," by Gustave Hahn.37

What was to become the first national Canadian circuit was begun in

the fall of 1906 by Bernard Allen and his sons Jay and Jule, American

emigrants from Bradford, Pennsylvania. They opened a store theatre (also

called the Theatorium) on Colborne Street in Brantford, Ontario, which

they equipped with 150 kitchen chairs and a bed sheet tacked on a rough

board frame for a screen. With its continuous show for five cents

admission, it was so profitable that the Allens could afford to spend

$2,000 equipping "The Wonderland," their second theatre in

Brantford.38 By 1909, the Allens had formed a film exchange

to serve their growing circuit. The chain soon spread to other western

Ontario centres, and eventually was expanded from Quebec to British

Columbia (Fig. 11).

11 A 1909 Allen Theatre in Berlin (Kitchener) Ontario. Handmade and

movie posters substitute for a marquee.

(Archives of Ontario.)

|

Another Canadian chain was started in 1906 by C. W. Bennett of

London, Ontario. Bennett Theatrical Enterprises were mostly concerned

with vaudeville theatres, though they operated several movie houses.

Bennett establishments could be found in London, Hamilton, Ottawa, St.

Thomas, Montreal, Quebec City, Saint John, Halifax and Sydney (Fig. 12).

The circuit foundered when it attempted to expand into South America. By

1909-10, its theatres had been sold, mostly to local businessmen.

12 Members of the Bennett vaudeville theatre

circuit. On the right, a closer look at Bennett's theatre, Ottawa (later

the Dominion).

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Bennett movie theatres were uniformly named "Unique," and seem to

have been little better than store shows, Bennett vaudeville theatres

were affiliated with the Keith circuit and were considerably grander.

"Bennett's," one of the circuits vaudeville theatres in Hamilton, was

a veritable jewel with decor of light green and red, with red

plush seats and red plush curtains in the boxes which were embellished

with cupids and floral designs and brass railings. The theatre even had

an isolated chamber for acts featuring trained

animals.39

It was designed by E. C. Horn of New York, and built in 120 days in

1907 (Fig. 13).

13 View of proscenium arch and stage area of the Savoy vaudeville

theatre in Hamilton, operated by the Bennett circuit between about 1907

and 1909.

(Famous Players Limited.)

|

Bennett's vaudeville theatre, which opened in December 1906,

introduced regular showings of moving pictures to Ottawa under the

patronage of the Governor General, Lady Laurier and the Mayor. Although

the movies were only a minor attraction on the bill, the Journal

reviewer enthused that they were "the best ever shown in

Ottawa."40 He was also fulsome in his description of the new

theatre's interior, which he judged as

handsome — decorated with many beautiful paintings and scenic

effects. Decorative effects in entrance are of Pompeian style with

Bacchante figures worked out to advantage. In the dome of the main part

of the ceiling, the paintings are magnificent, being worked out in old

Italian style. The centre figure represents music, with a fairy dancer

on one side and on the other figures representing music.

The paintings were the work of Frank Righetti of New York, and the

theatre's architect was E. C. Horn. In addition, the theatre provided 18

exits, a ladies' parlour with a "courteous maid," writing material and

recent magazines for waiting patrons, and a telephone messenger

service.41 For the next 14 years this theatre, renamed the

Dominion when the Bennett circuit expired, was Ottawa's "number one"

vaudeville house.

Within about a year of this theatre's successful presentation of

motion pictures in a permanent location, at least three store theatres

opened in Ottawa; the Unique (a combined penny arcade and auditorium)

and People's on Rideau Street, and the Nickel at 140 Albert.

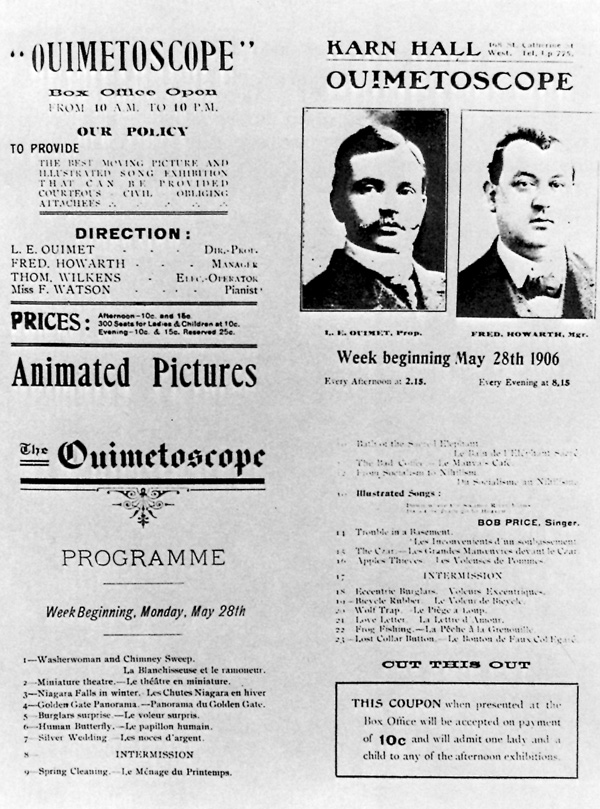

The year 1906 was also a key year for moving picture exhibition in

Montreal. In January L. Ernest Ouimet opened what was to become one of

Montreal's first successful enduring movie houses in Poire Hall, a

rented dance-hall and former vaudeville theatre on the corner of Ste.

Catherine and Montcalm streets. It attracted so many patrons that in the

spring it was closed for alterations. Its kitchen chairs were exchanged

for theatre seats, its capacity enlarged from 450 to 600, and another

entrance was provided on Ste. Catherine Street. Ouimet began imitating

legitimate theatre operations, offering two shows a day and "illustrated

songs," and reserved seats for 25 cents (Fig. 14). In April Ouimet

opened a similar house in Karn Hall, another rented dance-hall, between

Peel and Metcalfe on Ste. Catherine. He planned to shift the programme

from the first to the second "Ouimetoscope" after a week's run. The

second theatre (which was a second-storey establishment) closed about a

month later42 (Fig. 15). Nevertheless, the success of the

first Ouimetoscope seems to have generated such nickel theatres as the

Cinematograph Canada on St. James, the Starland and the Crystal Palace

on St. Lawrence, the National Biograph on Notre Dame Street West, and

the Nickel on Ste. Catherine Street West.

14 Exterior of Ernest L. Ouimet's "Ouimetoscope" one of Montreal's first

enduring movie houses.

(Canadian Film Digest.)

|

15 Programme of the second Ouimetoscope, with a photograph of its young

owner.

(Canadian Film Digest.)

|

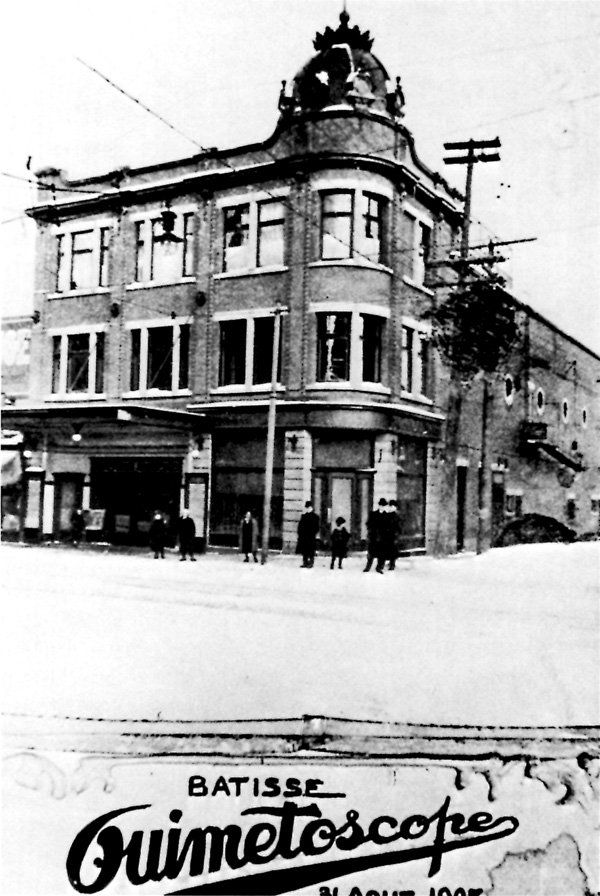

In May of 1907, Ouimet demolished his first theatre on Ste. Catherine

and Montcalm. A building even more significant was to take its place. He

opened on the site in August 1907 the first deluxe movie theatre on the

North American continent. This Ouimetoscope reportedly cost about

$50,000 and was one of the first movie houses constructed as such from

the ground up. With dimensions of 42 feet by 150 feet, it seated 1,000

in plush surroundings and offered such amenities as a tiled lobby,

reserved seats for 35 cents, a balcony, checkroom facilities and a house

magazine. It operated on a theatrical basis, with two shows a day and a

10-minute entr' acte. A seven-piece orchestra and illustrated

songs supplemented six reels of moving pictures (Figs.

16-18).43

16 Exterior of the 1907 Ouimetoscope, the first deluxe movie house in

North America.

(Canadian Film Digest; photo courtesy of National Film

Board.)

|

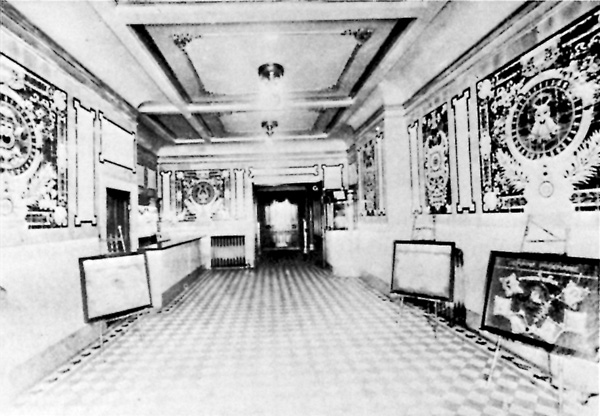

17, 18 Lobby and auditorium of the 1907 Ouimetoscope in January 1908.

The motifs on the tiled lobby walls depict theatrical muses. In the

auditorium, notice she orchestra pit, comfortable theatre seats, and the

decorated balcony and box fronts. Evidence of the check room can be seen

in the coatless audience.

(Canadian Film Digest; photos courtesy of

National Film Board.)

|

According to Ouimet, the only other building at all comparable to the

Ouimetoscope was a 1,000-seat movie theatre in Pittsburgh, apparently

built for the purpose in 1906 or 1907 by Sigmund Lubin. His theatre had

"an elaborate nickelodeon front," but unlike the Ouimetoscope operated

as a "grind" house with five- and ten-cent admissions; its entertainment

was two reels of moving pictures, one illustrated song and a piano

player.44

In general, between 1907 and 1910, moving pictures were neither

sophisticated nor long enough to warrant such exclusive surroundings,

and the Ouimetoscope did not long maintain its splendid programme, and

by 1910 had deteriorated to a "grind" house. Nevertheless, between about

1907 and 1912 many exhibitors relentlessly pursued respectability and

the "family trade" by dressing up their makeshift or newly built

theatres and by paying some attention to the comfort and safety of the

audience.

At first, most attention was concentrated on the building fašade.

Arched fronts (over the lobby and entrance doors) appeared at least as

early as 1905, and by 1909 they apparently graced the majority of

five-cent theatres. If they were symmetrical and proportional they

created a pleasing effect, but many were not and the feature came to be

known as a "Coney Island front"45 (Fig. 19).

The fairground or midway past of moving pictures could be recalled in

other exterior treatments which nearly put a circus wagon in the

shade.46 Lobbies and fronts were crowded with a profusion of

cheap plaster decorations (always called "gingerbread decorations" by

purveyors of good taste writing in Moving Picture World) which

were painted colours that "shout[ed] louder than the most leather-lunged

barker."47 A quantity of electric lights supplemented these

decorations, and were intended as enticements to passers-by, on whom

exhibitors largely relied (Figs. 20-22).

19, 20, 21, 22 Fašades of "new, improved" movie

houses. 19, A "Coney Island" front, Princess Theatre, Melville,

Saskatchewan. (Moving Picture

World.) 20, The Starland in

Calgary, ca. 1909, with very faint glimmerings of movie palace

glitter. (Glenbow-Alberta

Institute.) 21, The Starland in

Montreal dressed up for the coronation of George V, 1911. (Moving Picture World.) 22, A good example of gingerbread style —

the Majestic in Winnipeg in 1911.

(Moving Picture World.)

|

To this purpose, Sigmund Lubin had introduced in 1906 or 1907 pressed

metal fronts which were fitted over and camouflaged the old store fronts

and extended well above the first storey. These could be bought for

between $1,500 and $2,000 and, painted and strung out with electric

lights, were meant to suggest that a "real theatre" lay behind the

fašade. The 250-seat Starland, opened on St. Lawrence Boulevard in

Montreal in 1907, had a front of this type which, unfortunately, fell

victim to a fire not long after the opening.48

Other artifices to impress the middle class included "etched plate

glass mirrors," "tiled flooring," potted plants, and "artistically

framed" lithographs in the lobby area.49 The second storey

Red Mill in Hamilton in 1907 (and a number of other theatres which

possessed a flight of steps) dazzled patrons with "Rainbow Stairs."

These were made of glass, and covered running water illuminated by

varicoloured bulbs. The impression gained was that of walking up a

waterfall.50

Nevertheless, a nickelodeon patron was often ushered from a bright

and overdecorated front into a gloomy interior as, until indirect

lighting systems came into vogue in about 1910, interior decorations

could be considered virtually a waste of money. With the advent of aisle

lights and properly dimmed and shaded auditorium lighting, interior

decorations could be illuminated without interfering with the projection

of the picture.51 As well, patrons no longer had to grope and

stumble around in the darkness attempting to find empty seats.

By about 1908, folding chairs had given way to "cheap tip-up chairs

with veneer seats and backs." Unupholstered opera chairs also began to

appear in movie theatres. Exhibitors were counselled in 1909 that

"upholstered seats are not desirable...from any point of view," as

unupholstered seats were cooler in the summer and perfectly comfortable

for the comparatively short time patrons were seated. Nevertheless, in

about 1910 the spring seat with "pantasote" or fabric cover began to win

adherents.52

Other features common to legitimate and vaudeville theatres appeared

in some movie houses. These included sloped floors, balconies, waiting

rooms, toilet facilities for staff and patrons, and fire exits. The

phonograph and barker were replaced by a uniformed doorman and uniforms

were provided for the ushers. These advances, to some extent, kept pace

with the generally improved quality and entertainment value of moving

pictures, but as well, were often made in response to new governmental

regulations on safe moving picture exhibition.

Like Ernest Ouimet, other exhibitors whose makeshift theatres had

prospered began to build movie theatres from the ground up. However,

between 1907 and about 1911-12, this type of movie house was probably

the exception, and was by no means ipso facto de luxe. For

example, Vancouver's Maple Leaf theatre built in 1907 accommodated 500

kitchen chairs. Indeed, many flimsy structures were hastily put up, as

their proprietors did not expect them to last for more than one

season.53 Among the theatres of the new improved type that

were operating in Canada in 1911 were the new Starland in Montreal, the

Starland in Winnipeg, and the Princess in Vancouver. The Winnipeg

Starland seated about 750 and was served by a four-piece orchestra. Its

interior decorations were "in deep rose and bronze with many hanging

flower baskets."54 Shortly after its opening, a Moving

Picture World correspondent provided the following description of

the 450 seat Princess in Vancouver.

The front of the building follows in its general design the

Romanesque style of architecture. Inside, it is modern in every respect.

The auditorium is lighted by hundreds of softly colored incandescent

lights, so arranged that there is no glare, the light being thrown

against a mauve ceiling and reflected downward. The picture screen of

white satin is placed back of the proscenium arch. The arch is fringed

on the inner side by a beautiful decoration in art glass, through which

the lights shine softly....The slope of the floor is so arranged that

every person in the audience can see over a picture hat....On the right

side of the auditorium, at the side of the stage, is a comfortable

retiring room, with all modern accessories.55

It was the successful introduction of the multi-reeled or

feature-length film that demanded the most fundamental changes in

exhibition. High turnover, the basis of nickelodeon profit, was no

longer feasible.56 Furthermore, such feature-length moving

pictures as "Quo Vadis?" and "Judith of Bethulia" rivalled legitimate

productions in content, "class," and length, and needed more elevated

and formal screening surroundings than fusty nickelodeons. In New York

City, the producers of these features leased first-class Broadway

theatres and were confident enough to charge first-class Broadway

prices.57 The movies had achieved a measure of

respectability.

Henry L. Marvin decided to enter the exhibition field with the idea

conceived by Ouimet five years before: that motion pictures required a

special, "high class," expensive theatre. In February 1913 he opened the

Regent at ll6th Street and 7th Avenue, the first deluxe theatre built

expressly for showing movies in New York City (Fig. 23). From the Regent

it was a short step to the glorious excesses of the movie palace.

23 The Regent, opened in 1913, New York's first deluxe movie theatre,

designed by Thomas W. Lamb.

(Ben Hall Collection, Theatre Historical

Society.)

|

|