|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 13

All that Glitters: A Memorial to Ottawa's Capitol Theatre and its Predecessors

by Hilary Russell

Zenith—The Palaces

When the Regent opened,

bigger and more respectable theatres were being converted to the

showing of films. New York, in 1913, could count 986 movie

houses—of all kinds—though even the largest and finest of

these suffered from all the architectural ills of the day: tiers or

avalanching galleries supported by view-killing columns, hard wooden

"opera chairs," and becalmed ventilation systems.1

An architectural innovation which distinguished the Regent from

pretentious vaudeville houses and legitimate theatres of the time was

the replacement of the usual "double cliff hangers" by a single balcony

with a gentle slope and "exemplary sight lines." Instead of being the

usual obstructions in the orchestra. the supporting balcony columns were

set behind the last row of seats. This solution established a

first-class reputation for the Regent's young architect, Thomas W.

Lamb.2

The Regent also differed in dedicating "its operahouse splendor, with

its gilded stage boxes and fancy curtains" to motion pictures.

Nevertheless, for the first ten months of its existence, the Regent was

also distinguished by being a commercial failure. Its patrons were

"embarrassed and baffled to find all this grandeur surrounding something

as unimportant as movies."3 Then S. L. ("Roxy") Rothafel

burst upon the scene and transformed the place into a success.

It was Roxy's touch as the theatre's manager that set the tone for

its movie palace successors. He introduced rose-tinted lighting in the

auditorium, a new ventilating system and a scored orchestral programme

suited to the changing moods of the silent feature. The sound was

provided by a 16-piece orchestra, a separate string ensemble and New

York's first pipe organ in a theatre.4

In April 1914, Thomas Lamb's and Roxy's next theatre, the Mark

Strand, opened on Broadway and 47th Street, New York, and earned the

name of "Broadway's first genuine movie palace." Its decoration.

entertainment and staff were far grander than those of the Regent. The

Strand accommodated 3,000 in plush upholstered seats in an auditorium

"done as a sort of neo-Corinthian temple topped by a vast cove-lit

dome."5

The opening of the Strand's cosmetic suite was marked by a formal

tea, Richard Barthelmess and Marion Coakley, stars of "The Enchanted

Cottage," presiding. They were justified in celebrating "a lounging

room...of satin and rosewood, with gold leaf on hand-carved

decorations, and furnished in Louis XVI furniture and

tapestries."6

The Strand's splendid opening night so impressed the New York

Times drama critic in 1914 that he wrote,

Going to the new Strand Theatre last night was very much like

going to a Presidential reception, a first night at the opera, or the

opening of a horse - show....I must confess that when I saw the

wonderful audience last night in all its costly togs, the one thought

that came to my mind was that if any one had told me two years ago that

the time would come when the finest-looking people in town would be

going to the biggest and newest theatre on Broadway for the purpose of

seeing motion pictures I would have sent them down to visit my friend,

Dr. Minas Gregory at Bellevue Hospital.7

A series of articles in Moving Picture World in 1910 had

complained that the level of moving picture exhibition in New York City

was much lower than that found in other locations. The principal cause

of this disgrace was that the city's building laws prohibited the

erection of a moving picture theatre seating more than 300. Boston,

Philadelphia, Baltimore and Chicago—in fact, "all the great cities

of the Union"—could boast of up-to-date deluxe picture theatres

which provided for the creature comforts of their patrons. And this type

of theatre, the editor had been told, found "its best expression"

abroad, in London, Paris, Rome and Berlin. But in 1914, after the

openings of the Regent and the Mark Strand, the editor could assert that

"this country leads the world by a safe margin in the number of modern.

large and well-appointed moving picture theaters."8

Together the Regent and the Strand played a role similar to that of

the 1905 Pittsburgh nickelodeon in influencing the evolution of movie

theatre construction. The prerequisites for a movie palace were

established, though theatre buildings and their seating capacities,

stages, orchestras and theatre organs became bigger and more expensive,

their decoration and ushers gaudier, and entertainment programmes more

spectacular.

The main ingredients of a movie palace were a central location in a

large urban area, immense seating capacity, huge grand foyer and lobby

areas and extravagant, eye-popping decor. A movie palace was covered

with gilded plaster shaped into all manner of embellishment, and often

studded with classic columns, arcades of mirrors, and crystal

chandeliers. It was also characterized by palatial lounges and restrooms

and regiments of smartly uniformed ushers. Standard movie palace

equipment included galleries of oil paintings, acres of broad loom and

plush upholstered seats, damask and velvet draperies and a blazing

marquee. The palace's hallmarks were comfort, cleanliness and opulence.

It provided "super" stage shows and first-run film showings,9

accompanied by a mammoth theatre organ and a resident orchestra at the

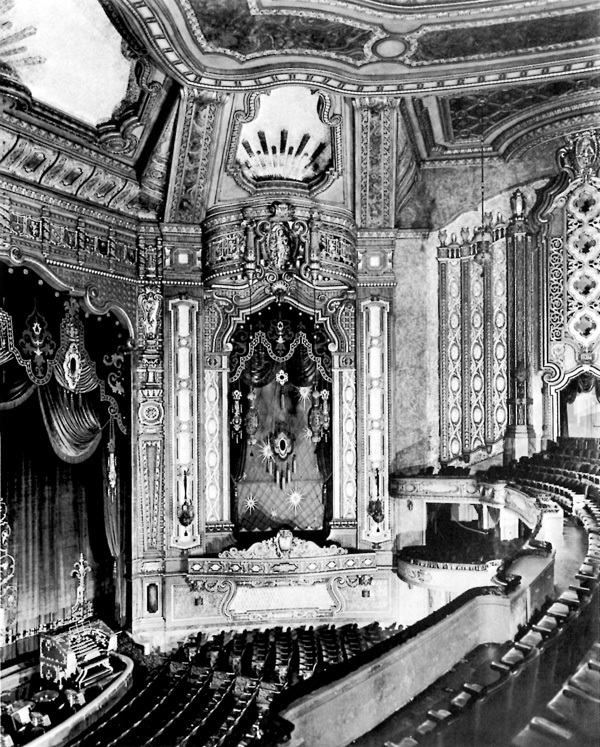

highest scale of admission for motion picture entertainment (Figs.

24-26).

24, 25 Decorative components of movie palace

flamboyance 24, Marquee of the Paradise theatre, Chicago, John

Eberson, architect. (Chicago

Architectural Photographing Company Collection, Theatre Historical

Society.) 25, Auditorium of

Ambassador theatre, St. Louis, George and C. W. Rapp, architects.

(Chicago Architectural Photographing Company

Collection, Theatre Historical Society.)

|

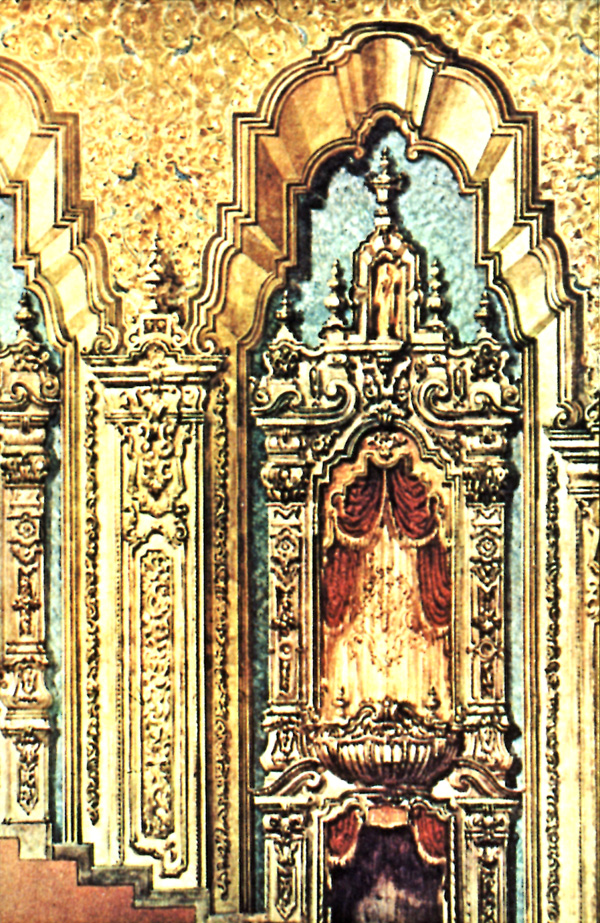

26 Drawing of grand foyer, Michigan Theatre, Detroit,

Michigan, George and C. W. Rapp, architects.

(Chicago Architectural Photographing Company Collection,

Theatre Historical Society.)

|

Only a few hundred of these palaces were built, and exclusively in

major metropolitan centres because of their cost and large patronage

requirements. Far more numerous were the deluxe movie theatres that

were built in small towns and in larger urban areas throughout the movie

palace era. The scale, entertainment programme and decor of a movie

palace distinguished it from a deluxe movie theatre. Movie palaces

might entertain 6,000 patrons and deluxe houses usually accommodated

under 2,000; compared to movie palaces, they had much smaller lobbies

and foyers, and fewer, less flamboyant ushers. Their stage shows, if

they offered any, were not as grandiose, and they were equipped with

smaller theatre organs and orchestras.

While the decor of most deluxe houses was mainly derived from that of

19th-century legitimate theatres, there were no limits to the sources

of inspiration for the movie palace architect, and no decorative style

or combination of styles was too excessive or outrageous to consider.

(Because of this, Dorothy Parker termed the movie palaces' decorative

style "early marzipan.")10 From 1914 to 1922 "Adam" and

"Empire" decorations were applied on a scale hitherto unknown, but

after 1922 nearly every decorative style known to man found its way

into the movie palaces (Figs. 27-29). Not only were Baroque, Medieval,

Moorish, Far Eastern, Persian, Hindu, Byzantine, Babylonian, Aztec and

Egyptian decorative themes translated into plaster and paint, but new

decorative styles were born (Figs. 30, 31). William Fox was offered a

choice between "Rolls Royce" and "Hispano-Suiza" decorations for his two

Detroit theatres by competing firms. He finally opted for "Eve Leo"

style, named after the distinctive decorative style of his wife, Eve Leo

Fox.11

27, 28, 29 A range of decorative styles employed by one movie palace

architect, Thomas W. Lamb. (Motion Picture News.) 27, Lamb

designs for the State Theatre, Syracuse, N. Y. Left to Right: study of

main ceiling detail of proscenium arches; detail of balcony arches.

28, Detail of sidewall balcony arches, Ohio Theatre, Columbus,

Ohio. 29, Stage and proscenium arch of the Plainfield Theatre,

Plainfield, N.J.

|

30 Dome in Fifth Avenue theatre, Seattle.

(Terry Helgesen photo.)

|

31 View towards the stage of Grauman's Egyptian theatre, Hollywood,

designed in 1922 by Meyer & Holler.

(Wurlitzer

Catalogue.)

|

In addition, ornamentations in legitimate and vaudeville theatres

tended to be concentrated on the auditorium ceilings, proscenium arches,

and balcony and box fronts. But the architects of these great

"democratic" theatres — the movie palaces —

tended to splash interior decorations from stem to stern.

The deluxe movie theatre was within the means of a small corporation,

or perhaps even an individual businessman. Movie palace ownership, on

the other hand, was virtually limited to vast multi-million-dollar

theatre-owning chains such as Loew's, Fox and Paramount, which usually

supplied motion picture and vaudeville entertainment to their theatres

from their producing companies and booking offices.

Because of the circuit ownership, many movie palaces resembled one

another, as a successful formula in one city would be applied elsewhere.

But there were intense rivalries between these powerful corporations,

and each tried to outdo the other in the largest urban areas in

providing magnificent showplaces for more and more lavish entertainment

programmes.

Of course, the grandiose theatres were primarily dedicated to showing

motion pictures, and after about 1932 they did this exclusively.

Numerous theatres of such size and magnificence would not have been

built if there had been no movies to present in them: moving pictures

were tremendously popular and were a cheap form of entertainment, both

for the patron and the exhibitor. Also the theatre was no longer limited

in its seating capacity by the necessity of seeing a performer's

features on the stage. Still, the stage attractions were an integral

part of the programme of a large urban theatre whose opulence in many

cases effectively complemented its grand stage and orchestral

presentations (Fig. 32).

32 A stage show rivalling the ostentation of movie palace decor.

(Theatre Historical Society.)

|

The evolution of the movie palace was closely related to major

developments in the motion picture industry. The impact of the

feature-length film has already been discussed. Further, a film like D.

W. Griffith's "Birth of a Nation" grossed millions, and

was seen by more people than had attended any classic stage

presentation in 50 years. It also had cost an unprecedented amount of

money. This aspect of film production became related to movie palace

architecture. Extravaganzas seemed to require extravagant

surroundings.12 On the correspondence between film content

and movie palace decor, a British author noted;

Many of the great cinemas seem imbued with the feeling of

particular movies. One can imagine the Babylonian orgies of

Intolerance among the Egyptian splendoors of Grauman's,... Lilian

Gish wanly isolated in the organ tower of the Astoria, Brixton, and

Douglas Fairbanks, sword in hand, leaping down from a toothed Moorish

arch in Finsbury Park.13

The palaces were monuments to the virility and permanence of a new

industry which not two decades before had inhabited ramshackle studios

and temporary theatres and had been considered by many to be a

manifestation of a passing fancy.

At the same time, the construction of movie palaces was an excessive

attempt by the industry to sweep its somewhat disreputable origins

under the rug. More was needed than rat-free, clean, ventilated

buildings to banish the middle-class prejudice against what had been

considered lower-class entertainment.

On the other hand, some of the most sumptuous palaces were built in

slum areas in large urban centres. Thomas Lamb declared that his palaces

were designed to lift the "average patron" out of his "daily

drudgery."14 George Rapp, another prominent movie palace

architect, justified the flamboyance of his buildings.

Watch the eyes of a child as it enters the portals of our great

theatres and treads the pathway into fairyland. Watch the bright lights

in the eyes of the tired shopgirl who hurries noiselessly over carpets

and sighs with satisfaction as she walks amid furnishings that once

delighted the hearts of queens. See the toilworn father whose dreams

have never come true, and look inside his heart as he finds strength and

rest within the theatre. There you have the answer to why motion picture

theatres are so palatial.

He went on to say, "here is a shrine to democracy where there are no

privileged patrons. The wealthy rub elbows with the poor —

and are better for this contact." Harold Rambusch, head of a major

decorating firm, had another view. "In a sense, these theatres are

social safety valves in that the public can partake of the same luxuries

as the rich and use them to the same full extent."15

The palaces provided a good deal of the excitement of going to the

movies. They could even be a consolation if the feature was

disappointing. The gilded palaces were "just like in the movies," and

were designed to put the patron in a mood receptive to the entertainment

offered. According to the most renowned showman of the period, S. L.

Rothafel, "theatre entertainment...takes place, not only on the stage,

but in the box office, in the lobby, the foyer, the restrooms, and the

auditorium itself....As a consequence, the architects' work has a direct

bearing upon the commercial success of the theatre he

designs."16

The gaudy, giddy, glorious movie palaces occupied a brief era in

American history which lasted less than two decades and spanned two

international crises, the Great War and the Great Depression. In Canada

the movie palace era was even more brief; it began in earnest after the

First World War had ended. Its boom years were between 1919 and 1921.

Comparatively few palaces were built in Canada after 1921, as by then

there were enough of them to satisfy the requirements of most large

urban populations in Canada. As well, the Canadian palaces do not bear

comparison with such great circuit showpieces as the Capitol or

Paramount in New York, the Avalon in Chicago, the Midland in Kansas

City, or the San Francisco Fox. In Canada, however, numerous deluxe

movie theatres and "combination" houses (which offered both vaudeville

and movies) were built between 1912 and the end of World War I (Figs.

33, 34). Among these were Halifax's 1,160-seat Casino, opened early in

1917 with a green, gold and pearl interior and a "Thermo" system of

ventilation, and the Imperial in Saint John, opened in 1913. Built by

the Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit, the Imperial vaunted six boxes, a

balcony, and 1,800 seats, 800 of which were leather-upholstered. In

addition to a "women's parlour" and a "men's parlour", it offered "a

rest room for children." A large chandelier in the auditorium

illuminated a colour scheme of "old rose, old ivory and Moorish tints

with gold."17

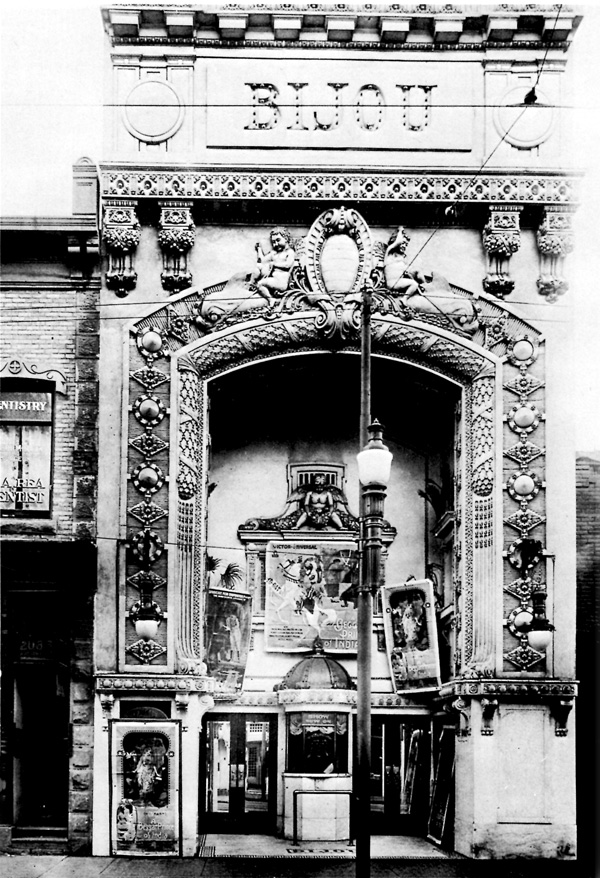

33, 34 Pretentious fašades from 1913 and 1914.

33. Calgary's Bijou, a movie theatre built in about 1914.

(Glenbow-Alberta Institute.) 34 The National Theatre (previously the Victoria)

in Winnipeg in 1918, a combination house opened in 1913. (Manitoba Archives.) (See p. 34.)

|

In Quebec, the most splendid deluxe houses were, not surprisingly,

erected in Montreal. In this category were the Colonial, Family,

Imperial, and Strand, built between 1912 and 1913, and the Regent and

the St. Denis, opened in March 1916. Of this group, the St. Denis was

the most remarkable and seems to have been Canada's first movie palace.

It reportedly cost well over $1 million to build, seated over 2,500,

and employed a 14-piece orchestra and a "$30,000" Hope-Jones Unit

Orchestra (or theatre organ). Though stage shows were included in its

programmes, the primary entertainment was moving pictures.18

Moving Picture World provided the following description of the

theatre's interior in 1918;

The decorations...are pleasing, being carried out in classical

style with the utmost refinement and restraint. Instead of having

draperies enhancing the beauty of the interior the desired effect is

achieved by stucco, worked in bas-relief, painted in cream, gold and

blue. On the walls and ceilings a certain richness is obtained by

medallions...from the Italian period. The great sunbursts over the main

boxes could be characterized as Egyptian. While the general squareness

and simplicity of the whole design is Greek. Thus, although no one

period of art has been adhered to, ideas have been drawn from every

country to form one complete and satisfying whole.19

The Gazette reviewer at the opening had characterized the

decoration of the auditorium differently; to him it was "a free

interpretation of the Adams [sic] style depending chiefly on

color schemes to emphasize the decorative effects instead of using the

familiar plaster figures."20

Despite these attractions, the first Canadian movie palace was a

white elephant for at least the first two years of its existence. Its

lack of patronage was explained as the result of a poor location, far

from the theatrical centre. As well, a Moving Picture World

correspondent surprisingly recorded, the bane of the St. Denis'

existence was that it was smack in the middle of a French Canadian

district, and "the French-Canadians are not theater going people, as

years of statistics and experience have proved."21

The St. Denis' closest Montreal rival in size and decor was the

Imperial which originally seated over 2,000 and was built by the

Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit. Its foyer and lobby were decorated with

"marble wainscoting," "fumed oak" woodwork and bronze chandeliers, and a

"broad marble staircase" led patrons to the mezzanine. Ivory, gilt and

old rose were prominent colours in the auditorium, which was graced by a

"huge bronze chandelier," loge boxes, large plaster figures above the

sidewall arches, and a Wurlitzer theatre organ, probably the first in

Montreal.22

Though not in the same league as the St. Denis, the 850-seat Strand,

the 650-seat Colonial (built in 1912-13) and the 1,000-seat Regent

(opened on the same day as the St. Denis) were deluxe photoplay houses

which catered to "fashionable" clientele. The Strand's exterior sported

"green mosaic" decorations, the Colonial's lobby was domed and lined at

floor level with "marble tile," and the Regent's wall panels were

"finished in imported French silk tapestry."23

Among notable deluxe photoplay and combination theatres built in

western Canada were the Dominion and Rex in Vancouver, opened in 1912

and 1913 respectively; the National and Pantages in Winnipeg, opened in

1913 and 1914; Pantages in Edmonton, opened in 1913, and the Allen in

Calgary. Of these theatres, probably the most unusual decor belonged to

Vancouver's Dominion. The dome in the auditorium was partly composed of

ornamental art glass in amber, green and red. The effect produced was

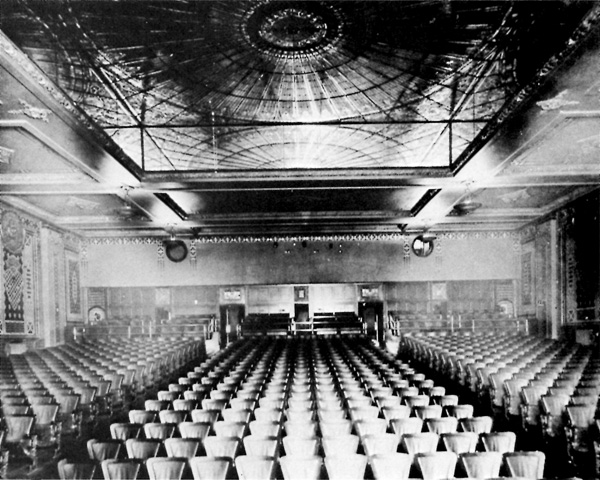

enhanced by judiciously placed mirrors24 (Fig. 35).

35 The glass-domed auditorium of the Dominion Theatre, Vancouver

photographed in 1924.

(Famous Players Limited.)

|

The Calgary Allen was built in 1913 and was the Allen chain's first

deluxe theatre. It accommodated 840, had a "commodious" balcony, and

offered organ accompaniment for its movies (Figs. 36-37). This theatre

received considerable attention in sources consulted. In 1919 it was

called "the first really modern house in Canada," and in 1925 "the first

[in Canada] of the large and impressive exclusive picture

palaces."25 In 1913 the Allen may have had the most

comfortable seats, the best projection and the largest balcony of any

Canadian movie theatre, but its designation as a "palace" is probably

unjustified. Compared to other exclusive movie theatres of the time, its

interior was elaborately decorated but, unlike subsequent movie palaces,

the decorations used neither rivaled nor surpassed those of a legitimate

or vaudeville theatre.

36, 37 Calgary's Allen theatre. 36, Fašade;

the murals on the left and right behind the columns on the second floor

perhaps serve to give the impression that the fašade is a Hollywood

false front. (Glenbow-Alberta

Institute.)37, View of

auditorium from the balcony in 1930. The organ "pipes" are exposed, as

they would be in a church. Later, it became fashionable in movie theatre

architecture to obliterate the memory of the organ's church past, to

conceal the pipes and to display the console prominently. (Famous Players Limited.)

|

Like the Calgary Allen, Toronto's Regent theatre, opened in August

1916, figured prominently in sources consulted. It was the first house

of what became the biggest Canadian theatre chain — Famous Players

Canadian Corporation — and was Toronto's first super-deluxe theatre

dedicated chiefly to movies (Figs. 38. 39).

38, 39 Photos taken about 1924 of the Regent's fašade and auditorium.

According so a Mail and Empire review on 26 August 1916, the

interior was "finished in white and gold, the effect being uniformly

rich."

(Famous Players Limited.)

|

This is not to say that no grand Toronto theatre exhibited movies

before 1916. Between the Theatorium opening in 1906 and the opening of

the Regent, four large and luxurious combination houses had been built

in the city; Shea's Victoria opened in 1910, Loew's Yonge Street theatre

in December 1913 and its bizarre roof-top Wintergarden two months

later, and Shea's Hippodrome in 1914.26

Unlike the other deluxe movie theatres that have been mentioned, the

Regent was a rebuilt legitimate theatre. It had opened as the Toronto

Opera House in about 1880 on Adelaide near Bay. Its programme had

deteriorated to "lurid melodramas" by the time it became the Majestic in

1902. By about 1910. it had been turned into a combination

theatre.27

In 1916, N. L. Nathanson, E. L. Ruddy, J. P. Bickell, W. J. Sheppard,

and James Tudhope formed the Regent Theatre Company and converted the

Majestic into the Regent which they advertised as "Toronto's beautiful

picture playhouse — the finest theatre of its kind in

Canada."28 Thomas W. Lamb was the architect of this

transformation. He arranged for the theatre's two balconies to be replaced

by one with a "long, easy gradient," and for the construction of a

mezzanine floor and lounge rooms. "The seating arrangement, interior

decoration and street front were entirely changed;" little remained but

the walls of the original theatre. The final product seated 1,475, and

also accommodated a 14-piece orchestra and a theatre

organ.29

Like the New York Times critic at the opening of the Mark

Strand, the Mail and Empire reviewer at the Regent's opening was

inspired to recall the bad old days of the movie theatre,

When the first local moving picture theatre opened... some years

ago in an out-of-the-way corner that had not proved much use for

anything else, undecorated walls that were thick enough to keep out the

light, plain, hard chairs that left kinks in a person's back, and a

white curtain were considered good enough equipment for the experimental

enterprise. No one would have prophesied in those days that the time

was coming when the opening of a theatre for screen drama would be a

social event. Last night saw a gathering for the formal opening of the

Regent theatre that indicated how much the movies has [sic] risen

in dignity in the past decade. There was an automobile line on Adelaide

Street that looked as though the season was at its height with a big

attraction playing at a legitimate theatre.30

At least one person in the opening night audience was slightly

disappointed. Bill Gladish reported in Moving Picture World.

An unfortunate part of the opening was that the house was not

quite finished, The $11,000 Cassavant organ was not ready for use

while several features of the handsome structure required finishing

touches. There was sufficient in evidence, however, to arouse the

unqualified admiration of the gathering. It was something entirely new

for a Toronto audience to find itself able to roam through the

promenade, reading, reception, and rest rooms — all richly

furnished and well aired....The aisles and stairs of the house are

covered with rich red carpet, while the general decorations are of the

so-called Adam's period, gold and blue in color.31

In 1917, the 1,700-seat Allen theatre (later named the Tivoli) was

built at Richmond and Victoria, apparently to "outdeluxe the

Regent."33 These two theatres were the first shots fired,

so's to speak, in a theatre-building war between the Allens and the

Nathanson circuit — later Famous Players Canadian Corporation

— during which most of the Canadian movie palaces were built, as

these circuits vied for patrons "with the energy of peacocks in a mating

dance."34

The Toronto Allen was the circuit's first luxury theatre in eastern

Canada, and "the first large house [in Toronto] to be constructed from

excavations to roof for the picture projection."35 The

interior was decorated in the by then familiar Adam style, predominant

colours being old rose, gold and grey. But it also contained some

features unusual for a large Toronto theatre. No stage as such was

provided, and the organ were installed in an area immediately under the

screen. As well, access stairways were replaced with inclined ramps, and

instead of a balcony or gallery. tiers of seats were built up in Roman

amphitheatre style (Figs. 40-42).36

40, 41, 42 The Allen (later she Tivoli) in Toronto, C. Howard Crane,

architect. Photos taken in October 1930. This theatre, unlike the Regent,

was built for movie shows. The geometrically decorated panels in the

auditorium and foyer were probably recent additions, and do not

harmonize with the interior's overall Adam derived decorative scheme.

(Famous Players Limited.)

|

Following the opening of this theatre, the Allens quickly won the

first campaigns of the circuit war. By 1919 the Allen circuit was

predominant in Canada, controlling 45 theatres in many major

metropolitan centres (see Fig. 119). In 1920 it was operating

nine showy theatres in Toronto (all with capacities under 2,000) —

the Danforth, Parkdale, Beach, Beaver, St. Clair, Bloor, College and

Royal as well as the original Allen.37 Two of these —

the Royal and the Beaver were bought ready-made. The rest were designed

for the Allens by C. Howard Crane of Detroit, a noted movie-palace

architect who was responsible for nearly every Allen theatre built in

the circuit's golden years.

Among Crane's other Canadian designs were the Allen (later the

Capitol) in London, opened in 1918; the Allen (renamed the Metropolitan)

in Winnipeg, opened in 1919; the Allen (later the Strand) in Vancouver;

the Allen (later the Capitol) in St. Catharines; the Allen in Windsor

and the Walkerville in Walkerville (whose names were changed to Palace

and Tivoli respectively), all opened in 1920; the Allen (renamed the

Palace) in Calgary opened in 1921; and Allen's Palace in Montreal,

opened the same year (Figs. 43-45). The Montreal theatre was the only

house that Crane and the Allens built in Canada with a seating capacity

of over 2,500; naturally, it was their most spectacular Canadian

effort.38 The opening programme was in keeping with the

extravagance of the theatre (Fig. 46).

43, 44, 45 Three more examples of C. Howard Crane's Canadian designs.

43, Mezzanine foyer of Metropolitan theatre (previously Allen) in

Winnipeg. 44, Auditorium of Walkerville theatre (later the

Tivoli) in Walkerville. 45, Grand foyer and rear of auditorium of

Allen Palace in Montreal.

(Famous Players Limited.)

|

46 The Allen (Palace) opening programme, Gazette (Montreal), 13

May 1921. The following description of the Allen's opening programme by

a Gazette reviewer on May 16 may give tome idea of she

"atmospheric illustrations" providing: "The Overture [was] followed by

the anvil chorus illustrated by a modern smithy scene set and a

quartette of... voices. The tableaux which included real fire struck

from the iron being effectively placed on either side of the stage

between the Cornithian columns [sic). The Miserere from ll

Trovatore followed with the background of the prison and afterwards the

famous duet from the final act of Rigoletto and the Donna e Mobile

aria."

|

C. Howard Crane adhered to the "standard" or "hard top" school of

movie-palace design. More or less following the Beaux Arts tradition of

opera and vaudeville houses, the movie-palace architects in this

"school" employed conventional neoclassical motifs and designs for their

"basilica-like emporiums."39

The dean of the standard school, Thomas White Lamb of New York, was

responsible for creating the largest and grandest Canadian movie palaces

(Fig. 47)40 He designed about 16 Canadian theatres between 1913 and

1921. Nine of these had seating capacities exceeding 2,000, and the

Imperial (formerly Pantages) in Toronto with its capacity of 3,626 was

the largest movie palace built in Canada. (New York's Roxy, by

comparison, had a capacity of over 6,000.) To put Lamb's achievement in

perspective, it should be noted that only about 17 Canadian theatres

with capacities exceeding 2,000 were built before 1930 with moving

picture exhibition firmly in mind.

Besides Toronto's Regent and Imperial theatres, Lamb's other Canadian

commissions were four western houses for Famous Players Canadian

Corporation — all named the Capitol — in Winnipeg, Calgary,

Vancouver and Victoria. He was the consulting architect in the 1927

rebuilding of what became the Capitol in Quebec City.

He designed the Capitol (formerly the Temple) in Brantford (his only

Canadian theatre not commissioned by one of the big circuits), the

Capitol in Montreal, and all the vaudeville-and-movie theatres built for

the Loew circuit. These included Loew's Yonge Street theatre and

roof-top Wintergarden, opened in 1913 and 1914, and, between 1917 and

1921, Loew's Uptown in Toronto, Loew theatres in Montreal, London,

Windsor, Hamilton, and Loew's Ottawa theatre.

|