Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 13

All that Glitters: A Memorial to Ottawa's Capitol Theatre and its Predecessors

by Hilary Russell

Sound

The decoration of the Capitol and other movie palaces had no

constructional significance, and may have been wasteful and excessive in

the view of modern theatre architects, but according to Theodore Jung,

architect, colleague and relative of Thomas Lamb, these decorations

were not without acoustic significance. Although the design of movie

palaces, with their long, raking balconies and ever-present domes, would

seem to have presented a host of acoustical problems, such were lacking

in the majority of Lamb's theatres.1

Acoustically, said Mr. Jung, a movie palace required an uneven

surface. The grilles and various ornaments broke up and absorbed sound

waves, thus preventing unpleasant echoes. Draperies and textile panels

in the auditorium performed the same function. Sometimes under these

textile panels there was additional sound-absorbing material like

Ozite.2

Movie palace sound did not emanate from a series of speakers in all

areas of the auditorium, but from the orchestra pit, the front portion

of the stage, and from the organ grilles. Mostly musical sound waves

were deflected from the sounding board to all parts of the auditorium.

The sounding board was the curved ceiling area between the proscenium

arch and the farthest reaches above the sidewall arches. Its surface was

relatively unbroken, and usually displayed a large mural in keeping with

the rest of the house decorations (Fig. 113).

113 Another view of the Capitol's sounding board, to show the relative

positions of the organ grilles in the sid-wall arches (to the left and

right of the sounding board) and the auditorium dome.

|

An additional "sounding board" was found to be necessary after the

Capitol's orchestra pit fell into disuse and was covered over, forcing

visiting orchestras to play on the stage. The Ottawa Civic Symphony had

a plywood backdrop built to prevent their music from escaping into the

fly tower. The Tremblay Concert Series also built a "sound barrier" that

rested on this drop.

In 1920, however. the orchestra played from the pit to accompany

vaudeville acts and silent movies. The sizes of these orchestras ranged

from 15 to 20 musicians in the smaller palaces like the Capitol to 40 or

50 in the biggest (Fig. 114).3 The orchestras alone were

often considered to be worth the admission price, and in pre-radio days

introduced millions to classical music.4 Many of these movie

palace orchestras had very good reputations, and sometimes formed the

nuclei of municipal symphony orchestras when their movie palace days

were over.5

114 The orchestra of the Palace theatre, Calgary, in an eastern mood.

The muscians have temporarily abandoned their positions in the orchestra

pit visible at the bottom of the picture.

(Glenbow Alberta Institute).

|

The musicians had to be competent in order to provide the appropriate

mood for swiftly changing scenes on the screen. The orchestra leader

constantly kept an eye on the screen to coordinate the musical

accompaniment. In the big palaces, he could mechanically adjust the

speed of the movie with dials on his conductor's desk.6

Many movies were furnished with cue sheets or specially prepared

scores, but the largest palaces usually employed a musical director who

imaginatively scored the movies that were to run in the theatre with the

aid of a large music library. Otherwise, conductors in smaller houses

relied on Erno Rapee's helpfully cross-indexed Moods and Motives for

Motion Pictures or some other text when no score was

provided.7

In a "Musical Suggestion Synopsis" published in Moving Picture

World in 1918. the following was proposed for the Metro production

"Her Boy:"

Theme for the Mother—Andantino. Suggest "Consolation," Liszt;

"Remembrance," Debussy, or "Melodie," Tschaikowsky. An emotional drama

taking place in the South. It is patriotic in the extreme, and will

require a medley of patriotic songs if possible. Many pathetic

selections are required with a Southern atmosphere to them. Use "Ol'

Kentucky Home," "Swannee River," etc., as fill in music for neutral

scenes. In the fourth reel soldiers are singing "We'll Hang the Kaiser

to a Sour Apple Tree." Use the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" as the

melody necessary. This should be followed by church music. Cue sheet can

be obtained from Metro Exchange.8

In nickelodeon days, a lone piano, or a little later on, a piano, a

violin and a set of drums had accompanied the short reels, not only for

entertainment purposes, but also to drown out the noise of the projector

in the auditorium.9 And only rarely did the accompaniment

have much rapport with the scene being projected. In reviewing the

performance of a pianist in an unpretentious movie theatre in 1911 Louis

Reeves Harrison wrote with some surprise, "she had evidently done some

thinking ahead, possibly she had read a summary of the plays in advance:

anyway she was on time at every change of scene with something suited to

the sentiment."10

In some nickelodeons, fitting sound effects were provided by someone

hidden behind the screen or elsewhere in the auditorium who was equipped

with whistles, hollow blocks, pistols with blank shells, pieces of

broken glass, and other miscellaneous objects. Some mysterious sound

effects were explained by an article in the Moving Picture World

in 1907:

The sound of horses' hooves upon a pavement is made very realistic

by the use of a pair of cocoanut shells which are applied to a marble

slab in a corresponding manner... Sand paper blocks...have a number of

uses; the escape of steam from a locomotive, splash of water and a

number of other effects are produced by this common

article.11

In movie palace days, a barrage of sound effects was combined in the

theatre organ, an instrument capable of imitating any orchestral sound

and then some (Fig. 115). The large four-manual instruments could

produce about 20 ready-made sound effects. Interestingly, these effects

were produced mechanically with some of the same instruments used in the

nickelodeon. To quote from a cinema organ guide, "horses hoofs are

simply half cocoanut shells clapped together by mechanical

means."12

115 The Mighty Wurlitzer. The Rudolph Wuriltzer Company's illustration

of their premise, "The Wuriltzer combines the world's finest pipe organ

with all the different voices of the Symphony Orchestra under the

control of one musician."

(Wurlitzer Catalogue.)

|

Theatre organs were standard equipment in movie palaces and any other

movie house of any pretensions.13 Theatre organs and their

lofts had no precedent in any other building, and were a movie palace

phenomenon. Organ solos could be attractions rating the marquee's

attention. As well, theatre organs provided ideal accompaniment for

silent movies. Combined with the ornamental grandeur of the house, the

theatre organ and orchestra gave the movie palaces their atmosphere,

transported their patrons from mundane concerns, and did away with

memories of tinkling pianos in stuffy nickelodeons.

The theatre organ was cheaper and more versatile in the long run than

a full orchestra. But no matter how wonderful its theatre organ was, no

movie palace could dispense with its orchestra, as it accompanied live

acts and was an added note of class. Neither could movie palace owners

afford to pay an orchestra to play for every show, and this was

also a physical impossibility for the musicians. Thus, many movie shows

were accompanied only by a theatre organ.14

Organ chambers (or lofts), usually located behind the sidewall

arches, accommodated the theatre organ's pipes and percussion with their

accompanying wind chests and swell shutters. These were controlled,

together with the blower generator and relay panel, by the console, and

were connected by hundreds of fine wires enclosed in flexible electric

cable and a metal wind trunk.15

This arrangement of pipes far away from the console was possible

because Robert Hope-Jones, the father of the theatre organ (or unit

orchestra), had devised "a system for opening and closing the valves in

the pipes with electromagnets, which were, in turn, controlled by

sterling silver electrical contacts under each key on the

console."16 Hope-Jones also invented the system of stopkeys

(usually arranged in a semicircle above the keyboard of the console)

which controlled the ranks of pipes at different pitches. The theatre

organist could thus change his stops easily and frequently to keep up to

orchestral and even dance-band tempos, unlike the church organist who

relied on clumsy draw stops. The theatre organist was assisted by the

pistons (white buttons) placed underneath the manuals (or keyboards)

which allowed him to change his combinations of stops

instantaneously.17

A standard 32-note pedalboard together with toe pistons worked

various ranks of pipes and sound effects. The balanced swell pedals at

the organist's feet controlled the volume of sound produced in the

chamber.18

Though it received a big build-up in the Ottawa Citizen at the

opening, the Capitol's organ (which was subsequently installed) was a

modest affair, with two manuals (the upper, solo and the lower,

accompaniment) and nine or ten ranks of pipes.19 It was

capable of no sound effects and could not even rise from the pit,

dramatically lighted. It was built by Warren and Son, Ltd., of

Woodstock, Ontario, primarily church organ builders. It contained such

stops as Fugara and Zart flute, abnormal to theatre organs. It did not

have a horseshoe console like more expensive organs. Its variously

coloured stopkeys were arranged in a straight line. It had eight pistons

for the keyboard which were only adjustable from the loft, and one toe

piston that brought in the full organ. It had a standard pedal-board,

and a crescendo and a solo pedal. The black paint on only the left hand

pedals was considerably worn down. Only a section of the console was

made of mahogany. The remainder was soft wood — possibly pine

— with a mahogany stain. The console was placed slightly under the

stage apron on the left of the orchestra pit.

Although two organ chambers were designed for the theatre, one behind

each sidewall arch, there is much evidence that only one of them had

been used.20 One chamber was bare of any hardware, save

brackets to support a windtrunk, and there was no take-off from the main

windtrunk that would have allowed an extension into the other

chamber.

There was a single phase, 400-volt, five-horsepower blower with

wooden casing and a metal fanwheel, together with a direct current

generator in a small, blocked-off section of the chamber. This was a

somewhat unusual arrangement, as ordinarily the organ blower was

installed in the theatre's basement. The remainder of the organ chamber

accommodated two windchests, one tremulant box, swell shutters, the

relay panel, and nine or ten ranks of wooden and metal pipes, as well as

the xylophone, harp and percussion instruments. All this hardware was

installed through an access door halfway up the exterior of the

building. The stairs leading to the door were removed after installation

(Fig. 116).21

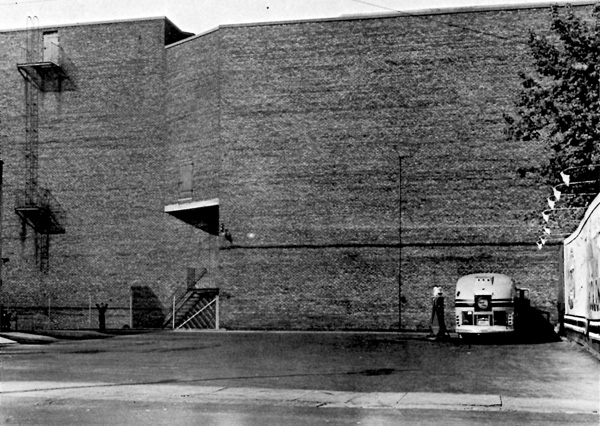

116 One of the access doors to the organ loft — accessible only by

ladder from the outside.

(Famous Players Limited.)

|

It is not certain exactly what duplication of stops occurred or how

many ranks the Capitol organ had as its relay board was too dirty to be

readable. The access door (leading outside) had been left slightly open

for years. Much of the chamber's equipment was smashed or removed to

make way for air-conditioning ducts in 1953.

The console was listed in an inventory as early as 1937 as being in

bad condition (Figs. 117-118). It was probably last played in about 1930

or 1931.

117 The neglected Capitol organ. (In contrast, see Figure 116, p.

111.)

(Geoffrey Paterson photo, 1969.)

|

118 The very fine Wurlitzer in the Portland Paramount.

The original's bench in the Capitol was similar to the

one seen here.

(Theatre Historical Society.)

|

The era of the theatre organ and orchestra came to an end more or

less with the introduction of sound movies. They caused a revolution in

all phases of the movie industry, in its production, personnel,

equipment and theatres. Contrary to popular belief, sound movies were

not first produced in 1926-27.22 Experiments had been made

ever since the inception of moving pictures, though an adequate

amplifier was first developed about 1914. Sound engineers were refused

financial support from the movie industry for a number of good reasons.

Producers had large stocks of expensive silent films suitable for a

world market, as well as actors and actresses under contract whose

dramatic technique was pantomine. (As well, some of them were illiterate

or could speak little English, thus could not read scripts.) Production

and theatre equipment would have to be bought or altered at enormous

cost to accommodate sound movies. Not the least consideration was that

silent films had attained good quality, were popular and made money, and

all experimental showings of talking movies had been obvious

failures.23

In 1927 Warner Brothers was facing bankruptcy, and joined with

Western Electric to produce "Vitaphone" sound movies, hoping such a

gimmick would save the studio. To the surprise of most observers.

talking pictures were an overwhelming success from then on. It soon

became apparent that "any sound film, no matter how bad, could fill any

theatre, however ratty, while across the street the most super silent

movie played to empty seats in the most sumptuous movie

cathedrals."24

It cost between ten and thirty thousand dollars to equip a theatre

for sound. By 1930, 234 different types of sound equipment were being

produced for theatres.

B. F. Keith's (later Ottawa's Capitol) first presented sound movies

on 27 April 1929. It was not enough to have the biggest and most ornate

theatre in Ottawa. Business had been affected adversely since the

Regent's sound installation, Ottawa's first, in December

1928.25 Other Ottawa theatres had been wired for sound while

Keith's was showing silent movies. A number of movie theatre managers,

including J. M. Franklin of B. F. Keith's, had announced in September

1928 that sound installations for their houses were imminent. According

to a Citizen report, the musicians "sort of climbed up on the

various managers' collective necks and retractions were in

order."26 As the Keith orchestra had signed a two-year

contract, the musicians sat in the pit until September 1931. For the

last six months they did not play a note.

The RCA Photophone engineer who supervised the installation at

Keith's announced that "about thirty miles of wire, two truck loads of

other accessories, and from 8 to 20 dynamic loud speakers" were required

to convert a big theatre. Through the "beam" system of sound

distribution and the proper placement of loudspeakers, the theatre was

"literally sprayed with sound", which was distributed to all parts of

the house with equal intensity.27

RCA Photophone was the manufacturing subsidiary of RCA organized in

1928. It produced both sound-on-disk and sound-on-film, the two

commercial methods of recording and producing sound movies, though it

was chiefly concerned with the former.28 RCA Photophone

projectors were equipped for both methods, like most other projectors at

the time, RCA Photophone equipment was designed and built by General

Electric and Westinghouse.

Sound movies eventually caused vaudeville to be discontinued in the

palaces. It became obvious to exhibitors that talking movies drew crowds

without this expensive additional feature. B. F. Keith's (Ottawa)

dropped vaudeville in June 1929. It was revived with great success in

September 1929, but was finally discontinued in May 1930. It was

presented intermittently in the 1930s, and even once in a while in the

1940s.

It is not certain precisely how acoustical considerations derived

from talking pictures affected theatre design. Dennis Sharp asserts,

The talkies created an immediate demand for a new type of

auditorium an acoustic box muffled to keep the sound in and

protected to stop noise penetrating from outside. It proved to be the

most fundamental change in cinema design since the industry

began.29

Surely theatres had not in pre-talkie days welcomed penetrating

street noises and escaping musical sounds. Movie palaces eventually

adapted quite well to sound movies, though of course they had not been

designed to be dotted with loud speakers. Initially, certain acoustical

problems like "sidewall echoes" and "standing waves" were reported but

these were solved by 1930 with the development of multi-cellular,

high-frequency horn loudspeakers.30

It is sometimes maintained that the "realism" of sound movies had a

profound effect on theatre design. "Music, talk, and natural noises were

not entirely in accord with the lavish unreality of the theatres or the

pastiche nature of their lush stage setting."31 This may be

true to the extent that sound movies limited the imagination of the

patron and made the theatre less of "a place to dream in." It seems that

the fundamental impact of sound movies was that they more or less

deprived the palaces of their stage shows, their lighting extravaganzas,

their orchestra, and their organs. Thus sound movies influenced theatre

architecture in that the theatres built after the decline of vaudeville

palpably needed no stages with huge proscenium arches,32 no

sounding boards, no orchestra pits and no box seats. Furthermore, the

success of sound movies indicated to movie palace magnates that very

modest houses could pack them in: the quality of the movie, not the

quality of the theatre, was the determining factor. Theatres built

thereafter were generally far less grandiose and less imaginative.

|

|

|

|