|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 13

All that Glitters: A Memorial to Ottawa's Capitol Theatre and its Predecessors

by Hilary Russell

"Lamb and Adam"

With the exception of the Wintergarden, all Lamb's Canadian theatres

generally resembled each other in their spatial organization and

decoration, though they differed in scale and scope. His auditoriums

were generally domed and supported large chandeliers; most of them had

elaborately decorated proscenium arches, ceilings and sidewall arches.

They were also characterized by large and extravagant colonnaded lobbies

and foyers, and elegant lounges and waiting rooms.1

The exteriors of Lamb's theatres were "invariably treated in the

classical manner, often faced with terra cotta blocks, simulating the

work of the masters of the Renaissance or facsimiles of parts of the

Louvre."2 Like most movie palace fronts, they gave only a

premonition of the glories that awaited inside, thereby reversing the

nickelodeon principle of a very flashy front and a more solemn

interior.

47 A 1928 portrait of Thomas W. Lamb.

(Motion Picture News.)

|

The interiors of Lamb's Canadian theatres (again, except the

Wintergarden) were decorated in the "Adam style." Until about 1925, Lamb

"hewed closely to the brothers Adam for inspiration, so much so that one

critic suggested, only half in jest, that the firm's name be changed to

'Lamb and Adam.'"3

The Adam style was derived from the unique decorative treatment for

the interiors of stately mansions and country houses devised by the

18th-century Scottish architect, Robert Adam (with the assistance of his

brother James).4

The Adam style could broadly be described as neoclassical with a

difference. Influenced by the domestic decoration of the ancient Romans

and the decoration and colour employed by the Cinquecento artists, Adam

departed from the prevailing English neoclassicism which demanded a

ponderous interior treatment with stereotyped forms and decorations

according to classical canons.5 Though Adam did not foresake

formal symmetry, he ignored these classical prescriptions, and lavishly

applied graceful plaster ornamentation devoid of any constructional

significance. He produced a fanciful, linear decorative style

characterized by lightness, movement and elegance and which was

calculated to "please the ladies." This was achieved by decorating the

wall panels, attenuated pilasters, entablatures and ceilings of his

interiors with plaster bas-relief ornaments which, until about 1780,

became more two-dimensional and tended to smallness of scale and

"subenrichment of enrichments,"6 "The result was antiquity

selected, rearranged, flattened, and made more decorative and more

elegant by an eighteenth-century master."7

Typical motifs in Adam decoration were arabesque and grotesque

decorated panels, combining such elements as flowing rinceaux,

anthemia, urns, confronting griffins and sphinxes, putti and swags. Adam

employed numerous elliptical, semi-circular. and circular forms in his

plans: paterae, rosettes, medallions, cameos, semi-circular tympani and

arched wall niches, lunette-shaped fanlights, semi-domes and octagonal

caissons. Many of his ceilings were built up of ovoids and concentric

circles (Fig. 48).

48 Design of the ceiling of the library or great room at Kenwood,

Robert Adam, architect, 1767. Many of the typical Adam motifs listed can

be seen in this illustration.

(B. T. Batsford, The Decorative Work of

Robert and James Adam, 1901.)

|

The richness and delicacy of Adam's decoration depended also on his

use of colour.

It appears that Adam very early conceived of coloured grounds and

white decoration, with judicious use of gilding; that his colours while

sometimes pale were often full bodied and strong, that the colours were

not limited to pastel tints generally thought of as "Adam; that the most

important place for colour in an early Adam room was the ceiling, but

that by the mid-1760's his walls were equally colourful; and that he

was not content with the mere "picking out of details with

colour."8

The Adam style was extremely popular in England and Scotland up to the

reign of George IV. Its influence percolated through English society

until it was manifested in the embellishment of small houses and

village shopfronts and the designs of silversmiths and makers of

Sheffield plate.9

The Adam style was also influencial in Canada and the United States

until the 1830s.10 in the United States, Adam's ideas were

spread by the brothers' two-volume The Works in Architecture, by

architect Asher Benjamin's publication The American Builder's

Companion, and by the work of such New England architects as Samuel

MacIntyre and Charles Bulfinch. Adam motifs also appeared in the

furniture designs of Thomas Shearer, George Hepplewhite and Thomas

Sheraton. The Adam style was not transferred undiluted to America, but

was modified and complicated in personal, imaginative versions developed

by its adherents.11

Though it declined by 1820 in the hands of the "New York School" into

a profusion of "attenuated, overwrought ornament," the style again

became popular in the United States and Canada in the so-called Beaux

Arts period when artistic and architectural styles of all sorts were

revived by artists and designers.12

Thomas Lamb no doubt encountered this revival when he was studying

architecture at the Cooper Union in New York. Lamb, a countryman of

Adam's, was born in Dundee in 1871 and emigrated to the United States in

his youth. Following his Cooper Union training, he worked for a short

time as a building inspector, and received his first theatre-designing

assignment from William Fox in 1909.13

Fox's City Theatre, 14th Street, New York, was unlike the theatres

which later made Lamb famous. It was a small theatre, built according to

the prevailing "high class" ideas, with two balconies. It mainly housed

stage shows, though Lamb was requested to allow space for a projection

booth.14

Between 1913 and 1919 Lamb's reputation as a first-class movie

palace architect was firmly established. His Regent and Mark Strand

theatres, New York's first deluxe movie house and first movie palace,

have already been discussed. His next notable achievements were the

daringly stageless Rialto and Rivoli theatres in New York, both

impressively designed in Adam style. His tour de force was

New York's Capitol theatre, of unprecedented size and magnificence.

Its style was Adam and Empire; it seated 5,300 and it was the largest

theatre in the world at that time.

All these theatres came to be managed by S. L. "Roxy" Rothafel, who

ensured that the entertainment presented matched the decor and scale of

the buildings which housed them. Thus the combination of Lamb and Roxy

was pretty much directly responsible for the movie palace

phenomenon.

Lamb explained that he had adapted Adam designs to his movie palace

interiors because he "felt that this style of decoration most ably

reflected the moods and preferences of the American

people."15 Probably, the style was suited to Lamb's purposes

as it was both grand and familiar; it was a "living room" style that

conveyed the desired impression of elegance and costliness without being

intimidating and forbidding. As well, Adam embellishmnents, in low

relief, were relatively simple and inexpensive to reproduce in cast

plaster, compared to more involuted decorative styles.

Lamb must have felt that the moods and preferences of the Canadian

people were decidedly similar. The decoration of his first Canadian

theatre, Loew's Yonge Street, opened in December 1913, was a somewhat

heavy example of Adam revival. The theatre was chiefly intended for

vaudeville. But Lamb departed from his Adam predilections in his

decoration of Loew's Wintergarden. a vaudeville theatre built on top of

Loew's Yonge Street theatre.16 As it is the exception to

most generalizations that can be made about Lamb theatres up to 1920,

the Wintergarden is discussed in detail.

To reach the Wintergarden, the patron took one of three elevators

from the foyer of the downstairs theatre, or ascended seven flights of

stairs whose scagliola banister was swarming with chubby putti

interspersed with hefty rinšeaux and rosettes (Fig. 49). The

elevators and stairs terminated in a small foyer, decorated only with a

neoclassical plaster cornice and a plate reading "Strike your Matches

Here."

49 Grand staircase leading to the Wintergarden. Notice the original Loew

lambrequins and the gas fixture.

|

The recognizable Lamb features in the theatre's interior are the

well-designed sight lines and single curving balcony, and the balanced

proportions of the sidewall boxes and the proscenium arch. Instead of

Lamb's usual plaster decorations, leafy branches of real trees, dipped

in fire-proofing solution, were woven on lattices in the upper boxes and

on wires strung just underneath the sidewall arches, the ceiling and the

undersides of the balcony and the projection booth which, unlike his

later designs, physically projects into the auditorium. Some artificial

leaves and flowers are also suspended in these areas and the surfaces

are a mass of foliage (Fig. 50). The supporting pillars of the balcony,

ceiling and upper boxes, and the "columns" flanking the exit doors, the

proscenium arch and sidewall arches are decorated in plaster to resemble

tree trunks. In all the "engaged tree trunks" the plasterwork is

extended into plaster branches until they diminish into two-dimensional

painted branches and leaves. A full moon projects slightly from behind

the painted leaves on one side of the sounding board.

50 View from the Wintergarden stage. The auditorium's entrance doors

are in the right sidewall and are not visible. The stairway at the rear

leads to the mezzanine and balcony. The ceiling and the undersides of

the projection booth and balcony are hung with artificial wisteria

blossoms, real and artificial leaves, and "garden lanterns."

|

The rest of the theatre's decoration is painted. Trellises of

climbing roses, cleverly painted to give a three-dimensional impression,

abound in the sidewall arches. surround the proscenium and decorate the

balcony and box fronts. The trellis effect is taken up in the design of

the organ grills. A peculiar mountainous landscape rises unexpectedly

from the trellis above the proscenium arch (Figs. 51-52). The remaining

walls of the theatre (the rear wall of the auditorium and the hallways

and stairs between the balcony and orchestra and behind the boxes) were

painted to resemble a walled garden, teeming with creeping and flowering

plants, small exotic trees, birds and woodland animals (Fig. 53).

51 Sidewall arch with leafy, painted, and plaster decorations.

The organ grilles are over the doorways on the balcony level.

|

52 View of Wintergarden stage with "picture sheet" (screen)

lowered by rigging and accompanied by its own curtains.

|

53 Painted decoration in the mezzanine balcony.

|

Thomas Lamb may not have designed another theatre like the

Wintergarden, a presumption which is difficult to verify because of the

number of theatres he designed. Almost certainly it is unique in Canada.

It presaged the "atmospheric" movie palace interiors (which were

designed ten years later by John Eberson, and later still by Lamb),

whose domes were decorated to give the impression of a tropical sky

complete with stars and clouds.

None of Lamb's ensuing Canadian movie palaces differed radically from

the others (Figs. 54-57), and it is possible that one of his Canadian

theatres may have had an identical twin in the United States or

elsewhere. He built a trio of American palaces for the Loew chain

between 1929 and 1932 in which "the same castings for ornamental plaster

work, the same sets of detailed drawings, identical carpeting and light

fixtures — even the same elephants on the newel posts were

used."17

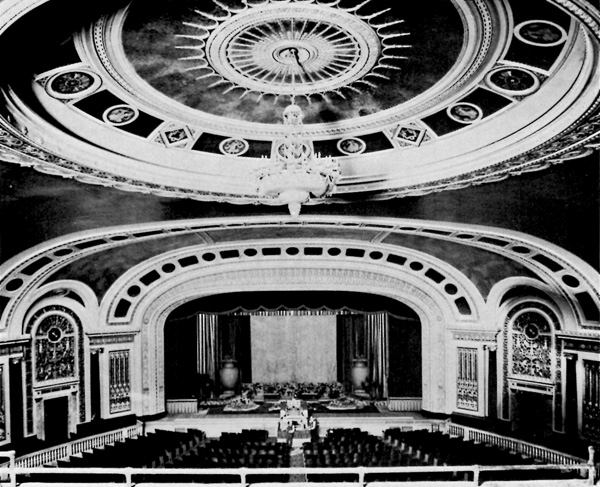

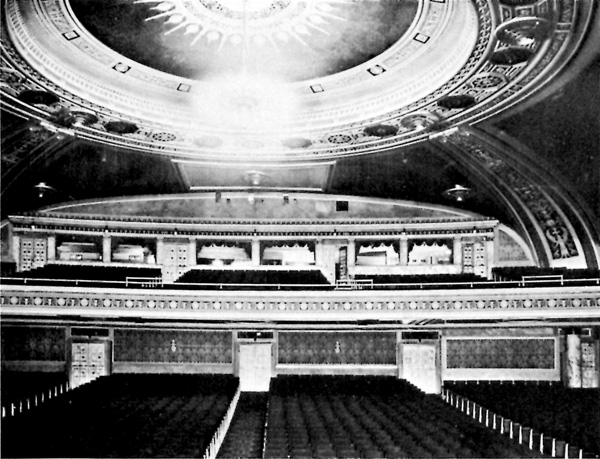

54, 55, 56, 57 Four similar Lamb auditoriums. 54, Capitol

theatre, Calgary. Photo taken about 1924. 55, Capitol theatre,

Vancouver, September 1930. 56, Capitol theatre, Winnipeg, May

1949. 57, Capitol theatre, Windsor, October 1930.

(Famous Players Limited.)

|

Cameos, medallions and arabesque panels were perhaps the most

frequent elements in the decorative schemes of his Canadian theatres. In

their auditoriums, the predominant colour scheme was old rose, gold,

ivory and grey.18 As well, in contemporary descriptions of

Lamb's new houses, such phrases as "Sienna marble," "wall mirrors,"

"brocade panels" and "crystal electroliers" tend to recur. Several

identical motifs could be found in more than one theatre. For example, a

cast plaster circular panel depicting dancing putti could be seen in

Loew's theatre in Montreal and Ottawa's Capitol. Replicas of the

"sunburst" chandelier in the auditorium of the Ottawa Capitol hung in

the Capitol theatres in Calgary, Winnipeg, and Windsor (Fig. 58).

58 One of Thomas Lamb's favourite auditorium chandeliers.

This one hung in the Ottawa Capitol. (See Figures

54, 56, and 57.)

|

Nevertheless, Lamb's stock Adam ornament appeared in new combinations

and, to some extent, certain theatres would seem to have called for

unstandardized architectural solutions (Figs. 59-61). For example the

Temple in Brantford, opened in December 1919, held 1,700 patrons on one

floor.

59, 60 Variations on a theme in lobby decoration.

59, Loew's Montreal, built in 1917. (Famous Players Limited, 1930.) 60, Capitol theatre, Vancouver. (Famous Players Limited, 1930.)

|

61 Capitol theatre, Montreal. (Photo taken in 1971.)

This theatre was not substantially altered during its

lifetime. It was demolished in 1974.

|

Another, the Imperial in Toronto, by contrast was the "largest

theatre in the empire" (Figs. 62-64). Certain features appeared in only

one of Lamb's Canadian theatres. The Ottawa Capitol's grand foyer had no

known equal, nor did the Montreal Capitol's great elliptical coffered

dome in the auditorium (Fig. 65).

62, 63, 64 Lamb auditoriums. The Temple, later the Capitol (62)

in Brantford, contrasted with another Lamb theatre without a balcony and

of similar capacity, Loew's, later the Capitol, in London, Ont.

(63), These bear little resemblance to Toronto's Pantages

theatre, later the Imperial (64), whose capacity was over 3,000

(Figs. 62 and 64 photographed about 1924; Fig. 63 taken in 1930.)

(Famous Players Limited.)

|

65 The auditorium of the Montreal Capitol. There is a

light fixture in each of the coffers.

|

Lamb trusted that the decoration of his theatres was "really

educational for those interested in...[architecture], in decorative

painting, modeling, etc." It was thus "essential for the architect to

follow a style to its most minute detail if he [wished] to avoid the

lash of criticism."19 Most of Lamb's theatres in Canada are

thus reasonably good examples of Adam revival in decoration as he

handled Adam motifs faithfully and with a good sense of balance.

But Lamb and those who followed his pedagogical approach sometimes

stimulated the strictures he sought to escape.

"This irresponsible reproduction of all the great architectural

treasures of the ages," wrote one horrified savant, "so cheapens public

taste that one wonders if a whole generation is not now arising whose

artistic appreciation will be so warped that in years to come, Americans

visiting the great sites of antiquity will be heard to remark: 'So this

is the Taj Mahal; pshaw...the Oriental theatre at home is twice as big

and has electric lights besides.'"20

|