|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 23

Gaspé, 1760-1867

by David Lee

Part II: The Fisheries of Gaspé

Par les yeux et par les narines, par la langue et par la gorge,

aussi bien que par les oreilles, vous vous convaincrez bientôt que,

dans la péninsule gaspésienne, la morue forme la base de la nourriture

et des amusements, des affaires et des conversations, des regrets et

des espérances, de la fortune et de la vie, j'oserais dire, de la

société elle-même.

Abbé Ferland

Of Cod and Other Fish

The fishing industry dominated all forms of life in Gaspé. As Abbé

Ferland observed,1 there was no way to escape the odour of

cod. Few people in the district were not dependent on the fisheries;

most men and adolescent boys worked on the fishing boats while the

women, girls and younger boys worked on the beach curing the fish. The

merchants, clergymen, doctors and lawyers who provided services in the

district were quite likely to be paid in fish. The fishermen bought

their store goods with fish and paid their church tithes with it; they

manured their gardens with fish and made soap from it. And naturally

fish dominated everyone's diet.

Abbé Ferland claimed that the Gaspé fishermen would not eat the best

quality cod, "la morue marchande" which was exported to Europe, because

they found it "trop insipide" and preferred the cod sent to feed the

slaves of the West Indies and Brazil, "la morue de réfection." They

shunned the good fish and ate "la chair tachetée [qui] dnéote que les

mouches y ont déposé leurs oeufs. Ces matières étrangères produisent de

la fermentation dans les parties voisines et leur donnent un goût plus

piquant." They also ate the lean parts of whale meat but not the blubber

although the Indians ate it.2

The Gaspé fisheries enjoyed two advantages over other dry-cod

producing areas in North America, particularly Newfoundland. Since

there was little spring fog in Chaleur Bay, cod could be caught and

cured up to six weeks earlier than at Newfoundland and spring was the

season when the cod swarmed in their greatest numbers along the shore.

However, the shipping lanes around both Gaspé and Newfoundland suffered

from the menace of icefields in the spring. On the richest Gaspé

fishery, extending from Cap des Rosiers to Cap d'Espoir, the season

lasted from May to mid-November and actually encompassed two seasons.

The spring and summer season was the most productive, supplying the

ships which left for Europe before the autumn freeze-up. The fall and

winter season consisted of whatever cod could be caught after the ships

left. Some of this fish was eaten locally, but most was sent to Europe

in the spring after the ice had left the shores. There was also some

winter fishing — "tommy-cod fishing" — done through the ice

of the St. Lawrence River.3

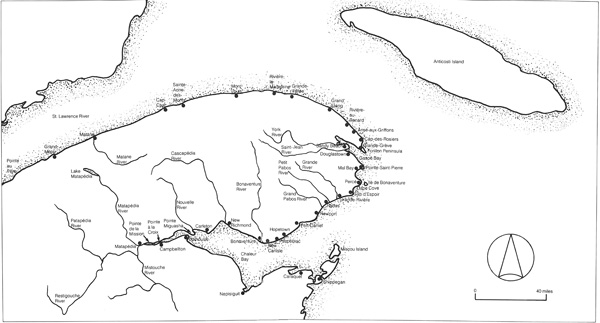

2 The Gaspé Peninsula.

(Map by S. Epps.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

The other advantage of the Gaspé fisheries was that the fishermen

had to go only two or three miles from shore to find plentiful fish;

thus, only small, relatively inexpensive boats were required. The

berges or chaloupes they used were 18 to 20 feet long in

the keel and 6-1/2 feet wide in the beam. They were outfitted with two

sprit sails, oars, compass, anchor and a small

cooking stove. They could carry up to eight quintals of fish, which

was more than the two-man crew could normally catch (or "make" as it

was termed in Gaspé) in one day. In a good year one berge could

make as much as 300 quintals. The berges were pointed at both

ends and appeared fragile, but were solidly made and could withstand

fairly heavy seas. Normally the keel was made of birch, the timbers of

cedar and the planks of pine or cedar; there was usually no deck. A

fisherman could buy a berge in 1777 for less than £8 and

by the 1830s they were reported to cost from "nine to ten Pounds in

goods or Provisions sold at an advance of about seventy-five per

cent."4

Larger vessels were employed in whaling and in fishing for cod on the

Orphan Banks, which were farther out in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The

"bankers" carried six to ten men and could stay at sea for a few days

until they were full. They were more costly and by the 1860s even the

large Gaspé fishing companies had given up and allowed the banks to

become dominated by American fishermen.5

No fisherman was truly self-employed for he was dependent on the

powerful merchants to purchase his fish and market it. The fishermen

were subject to three systems. Some men were employed directly by the

merchant-exporters to work on the firms' boats and beaches, and were

paid in credit at their stores. Most fishermen turned over their catch

to the merchants to pay for the provisions and equipment which they had

earlier been advanced on credit. A third group were those who worked for

la moitié de ligne; they worked for bourgeois who provided

the fishermen with berges and bait in return for half the value

of the fish that they caught. This meant that the two fishermen in each

berge each received only one-quarter of the proceeds of their

lines (and they supplied their own lines). The bourgeois received

all the fish at the beach and arranged for its curing and sale to the

exporters; the fisherman's share of the catch was then credited to his

account at the company store. Under this system the fisherman in effect

worked for the bourgeois, but received his payment in the end

from the large companies.6

Beginning in the late 18th century, shoremen were brought down from

the St. Lawrence river parishes to supplement local labour. The planters

had hiring agents in the parishes, of which Saint-Thomas-de-Montmagny

(near Quebec City) supplied the most men, and by 1820 their number was

estimated at 500 out of a total of 1,800 working on the Gaspé fisheries.

By the 1830s some were coming down to fish on their own. They were

considered poorly-skilled fishermen, but they were able to make a little

money by using the small, unappropriated beaches on the

north shore between Matane and Cap-des-Rosiers. In 1832 a few were

reported permanently settled at Sainte-Anne-des-Monts and in later

years others settled the north shore, eking out a living by subsistence

fishing, practising very little agriculture and cutting wood only in the

winter.7 Although spring and summer were the busiest times,

the winter, too, was a time of work. Wood had to be cut for fuel and

building purposes, some fishermen had a few chickens and occasionally a

cow to care for, and the fish-curing flakes on the beach and boats and

nets had to be repaired. Some were lucky enough to get a few weeks'

employment with the big fishing companies making the drums in which cod

was sometimes packed. There were also a few winter jobs with the whalers

making the barrels in which whale oil was exported.8

Few of these jobs paid workers in cash and, indeed, there was very

little cash to be found anywhere in the Gaspé economy. The fisherman

gained his necessities at the company store on credit and paid his

account with fish during the fishing season. For larger transactions

bills of exchange were used,9 but fish was the general medium

of exchange. The best source of capelin for bait was Grande-Rivière;

there the seigneur charged two and one-half quintals of cod for every

boat which came to gather bait. The Roman Catholic priests of Gaspé were

called missionaries, but the parishioners were expected to pay

something toward their subsistence. The tithe could be in the form of grain

or potatoes, but generally it was fish which the missionary could keep

for himself or redeem for goods at the company store. At Percé

parishioners were expected to pay the priest one-half quintal of cod for

every boat they had, but there, as in most places in Gaspé, tithing was

very irregular and unreliable; however, in 1838 the people of Paspébiac

agreed to pay their priest one-half quintal of fish per

family.10

Although the Gaspé fisheries had several advantages over competitors,

one problem of which the local industry was always aware was pollution

of the fishing waters. In 1765 a government surveyor visited Gaspé Bay

and suggested that the French might have diminished the local cod

fishery by throwing fish offal into the waters of the bay. The cod would

eat the offal instead of the bait offered by the fishermen and it also

hurt the quality of the fish that fed on the offal.11 Renewal

of the Gaspé fisheries under British sovereignty increased pollution. As

early as 1769 the problem was considered serious at Pabos and a petition

from the few residents complained particularly about the behaviour of

fishermen from the thirteen colonies to the south.

At a time when every Individual on the Continent seems Tenacious

of his liberty, permit us, the Poor & Ill-treated Fishermen of

Gaspey & Chaleur Bay [to complain about the] Number of Schooners

& deck'd vessels amounting to some hundreds yearly, from the

Southern Governments, which not only fouls the Shalop & Boat Fishing

grounds by the Distructive method of heaving over the Garbage of the

Fish, but even keeps within our Capes & Headlands. A practise so

distructive in itself that the French, was well aware of & punish'd

with the utmost vigor. . . . Let us humbly entreat the Sons of

Liberty, who knows us to be a conquer'd Government & naturely

polite, to give the Skippers of their Vessels for the ensuing year

strict orders not to Oppress us more than we are allready, by the

aforesaid practise, remembering that they themselves thought His

Majesty's Ship was an incroachment last year in Boston Bay,

notwithstanding she never foul'd the Ground with Cod heads or Sound

bones.12

Over the years numerous petitions were sent by Gaspé fishermen

imploring the government to impose and enforce laws prohibiting visiting

fishermen from throwing fish offal into the water.13 They

always blamed visiting fishermen and their accusation may have been

accurate; local fishermen found it easier to dispose of their refuse

and, of course, had a greater interest in the long-term welfare of the

fisheries. Legislation introduced in 178814 prohibited the

dumping of ballast in Gaspé harbours and of fish guts, offal or gurry

within two miles of shore, but it was not enforceable because of the

weak judicial system in Gaspé. Besides, the dumping of fish refuse

farther out at sea harmed the fisheries just as much for the cod was a

migratory fish. In 1824 the assembly passed new legislation which

forbade dumping offal within six leagues of shore.15

Americans were considered the worst culprits because not only did

they throw their refuse overboard, but also their fishing depleted the

supply available to Gaspé fishermen. Charles Robin noted in 1772 how

early the presence of American fishermen on the Orphan Banks was felt on

the Chaleur Bay fisheries.16 During the American

revolutionary war when very few fish were taken, Nicholas Cox noted that

the fishery quickly recovered.17 Americans who came later to

catch mackerel also affected the Gaspé cod fishery because the local

fishermen used the mackerel for bait to catch cod.18

The treaty of 1818 between the United States and Great Britain

forbade American fishermen to catch, dry or cure fish within three miles

of British territory though they could land for wood, water, shelter and

repairs; however, restrictions against coming ashore only meant that

they had to dispose of their refuse at sea. By this time, Gaspé

residents suspected that they dumped at sea in order to distract the cod

from leaving the banks to follow "their natural course near the

shores."19 M.H. Perley noted that although the "Crown

Officers in England" had interpreted that the three-mile provision

should be measured from the headlands, Americans were still fishing in

Chaleur Bay in 1850.20

Fish Production

It is difficult to determine the exact impact of American fishermen

on the Gaspé fisheries, but we do know that exports of most Gaspé fish

rose fairly steadily during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Codfish production for example, was reported to have been 28,000 to

30,000 quintals in 1777, the year before American privateers ravaged

the Gaspé fisheries,21 but during the years of the American

Revolution, cod production was probably no higher than that required for

local consumption. The fishery must have recovered quickly after the war

for 25,500 quintals were exported from Gaspé in 1784.22 During the 19th

century, exports continued to increase: in 1811 they were reported at

26,691 quintals and, with a few minor declines, rose to 62,747 quintals

by 1835. Statistics after this year are incomplete; however, exports

for later years have been found:

| Year | Number of Quintals of Cod |

| 1842 | 98,062 |

| 1848 | 80,339 |

| 1864 | 102,846 |

| 1865 | 120,278 |

| 1867 | 111,731 |

Total figures for cod exports would be higher for it was shipped in

other measures than quintals; for example, casks, hogsheads, barrels,

pacquets, caisses, tierces, kegs, firkins, bundles and boxes.

Other cod products exported included tongues, sounds (cod heads) and

cod-liver oil. Further, total cod production in the District of Gaspé

would have been even greater for a good deal was consumed

locally.23

In 1861 Gaspé Bay was declared a free port, thus attracting a great

deal of shipping to Gaspé; many of these ships took cod on their return

voyages. The destinations of the 351 ships which cleared the port of

Gaspé Bay that year are shown below.24

| Number of Ships | Destination |

| 15 | Great Britain |

| 6 | United States |

| 1 | Portugal |

| 119 | Spain |

| 112 | Nova Scotia |

| 32 | New Brunswick |

| 15 | Newfoundland |

| 32 | Prince Edward Island |

| 13 | Italy |

| 6 | Brazil |

Pierre Fortin, stipendiary magistrate charged with supervising the

fisheries in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, enumerated many examples of

shipping leaving the Gaspé district in his report for the year 1864.

Following are a few examples.25

(1) One Charles Robin and Company ship left Paspébiac in June taking

cod to Rio de Janeiro; it returned (via New York with freight) in time

to take a larger cargo of cod to Brazil again in November.

(2) Another made two trips to Boston early in the year; returning

the second time, it "touched at Sydney" to bring coal to Paspébiac, then

took cod to Naples in October.

(3) Another brought salt from Jersey in the spring; took cod, oats,

herring, shingles and other products to Barbados in June; returned with

sugar and molasses in September, and took cod to Brazil in October.

(4) J. and Elias Collas of Jersey launched a 94-ton ship from their

Pointe-Saint-Pierre shipyard in the fall which went to Portugal in

November with cod.

(5) A ship belonging to John Fauvel of Pointe-Saint-Pierre arrived

in Gaspé Bay in May from Jersey with general cargo, left for Cadiz in

June with cod, returned in ballast, and left in November to take cod to

Naples.

Although cod was the main source of income for Gaspésians, other

types of fishing were carried on. Whaling began in Gaspé Bay about the

turn of the 19th century; according to tradition, an American from

Nantucket instructed the Boyle brothers of Gaspé Bay in his methods of

whaling.26 Whaling, a high-risk enterprise, was never

actively encouraged by the government. It required a good deal of

capital even to begin because it required schooners large enough to

carry about 12 men and capable of operating on the high seas (primarily

the north shore of the gulf). One season of poor sailing weather could

completely ruin a whaler.27

Over the years the gulf whale population declined because of

overkilling and the whalers moved into the Strait of Belle Isle and the

Atlantic along the Labrador coast, but by the 1860s even these areas

were depleted. Fortin tried in vain to encourage the Gaspé whalers to

go farther afield, to the Greenland coast, for example; he claimed that

they were notoriously bad navigators and gave as an example the fact

that the ships taking Gaspé cod to the world markets were still captained

by foreigners (presumably Jerseymen).28

Little whale meat was exported. It was the oil, refined for

lanterns, which led men to pursue whales. The oil-refining operations were

based at L'Anse-aux-Cousins and Penouil in Gaspé Bay. The task of

reducing the blubber to oil and preparing casks for its handling is

reported to have employed about 100 people, employment which would have

lasted about two and a half months in the autumn after the whaling

season ended.29 Although the production figures shown below

are scanty, they indicate that whaling was a very capricious enterprise.

| Year | Gallons of Whale Oil |

| 1810 | 15,360 |

| 1820 | 18,000 |

| 1832 | 18,000-20,000 |

| 1861 | 33,600 |

| 1862 | 26,000 |

| 1863 | 14,400 |

| 1864 | 25,014 |

| 1865 | 14,420 |

| 1866 | 12,230 |

| 1867 | 25,890 |

In 1810 the 27 whales caught produced 480 barrels or 60 tons of oil;

valued at £31 per ton, the yield was £1,860. In 1864 oil was

valued at 65 cents per gallon.

Salmon exports from the Gaspé district generally came from the

Cascapédia and Restigouche rivers. Salmon experienced a dramatic decline

in mid-century and only strong legislative measures saved them from

extinction. Despite charges that the Restigouche Indians were the chief

cause for the decline, many other factors were involved. The Indians

were accused of taking salmon before they spawned, but it was Europeans

who totally blocked some streams with nets and dams for lumber mills or

who choked the rivers with sawdust. There had long been laws governing

the salmon fisheries, but there were no means of enforcing them until

the mid-1850s when Fortin was made stipendiary magistrate to oversee

the Gaspé fisheries. Subsequently an overseer was appointed for the

Restigouche River only; in 1861 he reported no breach in the fishing

rules and a consequent increase of 60 barrels caught in the river that

year.30 Fortin noted that a Mr. Price had constructed a

fine fish-way on the Matane River, but no salmon had been seen above it;

before Price's milldam had been built the river had produced 25 to

30 barrels a year.31

In 1790 the Restigouche River alone is estimated to have produced

6,000 barrels of salmon; by 1823 production had fallen to 1,000 barrels.

By the 1850s salmon had almost totally disappeared from the district,

but came back slowly during the following decade. The figures below

show the amount exported from the Gaspé district in the 1860s.

| Year | Number of Barrels |

| 1864 | 483 |

| 1865 | 517 |

| 1866 | 703 |

| 1867 | 950 |

In the 1860s sport fishermen using the artificial fly first began to

fish the magnificent salmon rivers of Gaspé and licensing of the sport

began to bring in some revenue. It was probably Jefferson Davis's visit

to Gaspé in 1866 (when he caught 160 salmon) that brought Gaspé salmon

to the attention of sport fishermen.32

Charles Robin mentioned gathering oysters as early as 1769, but they

never became a popular object of the Gaspé fishermen's search. In 1859

Fortin transplanted a number of oysters from Caraquet to Gaspé Bay

"according to the latest and most generally adopted European method."

Few survived and Fortin attributed the failure to the muddy bottom of

the bay.33

Many other fish were caught, especially for bait. Capelin, the chief

food of the cod, were netted along the shores of Gaspé and were also

popular for manuring local gardens, a practice which was later

forbidden. Capelin were especially plentiful at the beginning of the

fishing season, but if they became scarce as the season progressed, the

fishermen turned to herring, then mackerel and later even to squid,

smelt and trout.34 Other fish exported from Gaspé in small

amounts included pickled and smoked herring, trout, shad, eels, sardines

and mackerel.

Although mackerel were plentiful in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Gaspé

fishermen left them to American fishermen who pursued them with scores

of ships. Fortin particularly lamented the lack of adventure among Gaspé

fishermen who would not pursue whales to Greenland or take advantage of

local mackerel resources. The United States market was enormous and

American fishermen came long distances to fish in international waters

just off the Gaspé coast, but Gaspé fishermen preferred the easier life

of fishing for cod in coastal waters.

Sir William Dawson felt the Gulf of St. Lawrence mackerel fisheries

should be left to the Americans. Mackerel, he said, was a "vagrant,"

making the fishery unreliable from year to year. Further, fishing on the

open seas raised the risk of calamity; the cod fishery was much safer

and more dependable. Dawson added, "Our comparatively thinly settled

coasts could ill afford the frequent unsuccessful voyages and terrible

disasters and loss of life that attend the American mackerel

fisheries."35

It is interesting that lobsters, although abundant in Gaspé, were

never exported. Indeed they were seldom eaten locally, the fishermen

rejecting them as nothing more than a nuisance which often tore their

nets. Not until the 1870s when American businessmen set up canneries on

Chaleur Bay were the Gaspé lobster resources exploited.36

Gaspé Fishing Companies

Gaspé Bay and Paspébiac were the two major centres for the

exportation of cod and for the first 30 years of the 19th century two

Jersey companies shared the Gaspé fisheries on a non-competitive basis.

Francis and Philip Janvrin dominated the fisheries of Gaspé Bay and

even held shares in Charles Robin and Company, which controlled the

fisheries on Chaleur Bay, including Percé. Many smaller companies tried

to compete with the two large firms and some succeeded, especially later

in the 19th century, but many failed, particularly in the 18th

century.

In the period from 1760 to 1775 there were numerous traders, many

operating out of Quebec on a small scale along the coasts, who bartered

salt, fishing equipment and provisions, for fish, furs and skins. An

early example was William Van Felson, a native of Holland, who took a

15-ton schooner to Gaspé in 1763 with a cargo of "Sea stores &

utenzils for the fishery"; he continued trading at Bonaventure until the

American Revolution.37

Beginning in 1766 a Quebec-based trader, William Smith, with two

merchant partners in London had erected several store houses at

Paspébiac and Bonaventure and traded goods with the Indians for the

salmon they caught on the Cascapédia and Restigouche

rivers.38 As noted earlier, John Shoolbred took over these

operations but was driven out by American privateers in 1779.

Charles Robin first came to trade along Chaleur Bay in 1766 and, like

Van Felson and Smith, resided on the fisheries much of the time;

however, his supply base was Jersey rather than Quebec. Other

small-scale merchants who came to trade seasonally along the Gaspé

coast included a firm from Halifax.39

Guernsey fishermen who were also traders are known to have been on

the Forillon shore of Gaspé Bay by at least 1767.40 The LeMesurier and

Bonamy families are shown on a census of 1777 as having 17 fishing boats

and, besides their families, 58 people working for them (probably

brought in every spring for the fishing season). After the revolutionary

war the business was run by Thomas LeMesurier and his brothers and by

1789 they were reported to be bringing in 100 fishermen from Guernsey

every season and exporting 10,000 to 12,000 quintals of cod to

Europe.41 Charles Robin later commented that it was not a

profitable business and apparently the LeMesuriers sold out to the

Janvrins in 1792.42 Some of the Guernsey people, among them the Bonamy

and LeMesurier families, remained on the Forillon peninsula and were

joined by workers from Jersey brought out by the Janvrin

Company.43

Francis Janvrin was a shareholder in Charles Robin and Company as

early as 1787 and he and his sons continued as shareholders for at

least 50 years.44 The Janvrins, emulating the Robin firm,

established their first fishing operations at Cape Breton Island in

1783 and then expanded to the District of Gaspé. Although some of the

Janvrin family came out to Cape Breton to direct the fisheries there,

their operations in Gaspé were run by a resident agent who received

occasional visits from the Janvrins living at Cape Breton. Their first

fishing station, slow to prosper, was at Grande-Grève, but success

eventually came and the company flourished and expanded.

The devastating war in Europe in the first years of the 19th century

resulted in a greatly increased demand for fish and in response the

Janvrin company established new fishing stations at Gaspé Bay,

Pointe-Saint-Pierre, Mal Bay, Cap-des-Rosiers and Anse-aux-Griffons.

Their business was extensive, exporting dried cod to Brazil as well as

Europe. They entered an agreement not to compete in the North American

fisheries with some Guernsey fishing companies known as the "Arichat

and Gaspé Society." The Janvrins were to have no Guernsey competition in

Cape Breton and Gaspé Bay in return for not entering the Newfoundland

fisheries.45 Further, the Janvrins and the Robins did not

trespass on their respective fishing areas in Gaspé.

The Janvrins sold their fishing business — it is not known

why — to two Jerseymen who had been general managers for Charles

Robin and Company. John Fauvel, who had worked at Paspébiac, seems to

have purchased the Mal Bay fishing post.46 In 1857 William

Fruing bought the fishing stations of Gaspé Bay and the Forillon

peninsula. In 1861 the Fruing company was reported to be exporting

18,000 quintals of cod to several Mediterranean

countries.47

The Janvrins and their successors nearly monopolized the Gaspé

fisheries from Mal Bay to Anse-aux-Griffons. Only one merchant, the

Loyalist Daniel McPherson from Philadelphia, successfully competed with

the Janvrins, but he depended heavily on them for supplies.48

Charles Robin indicates that McPherson's "Fishery and supplying

business," established at Douglastown in the 1780s, enjoyed only modest

success, but by 1802 McPherson had gained enough to buy the seigneury of Ile aux

Grues (Crane Island) near Quebec to which he soon retired. His business

then appears to have been continued by his son John and son-in-law Henry

Johnston who added to McPherson's business by acquiring the Janvrin

properties at Pointe-Saint-Pierre49

Many investors had lost a great deal of money attempting to establish

fishing posts in Gaspé after the American Revolution and Robin lists a

dozen firms that failed with heavy losses.50 Charles Robin

flourished on Chaleur Bay, but only by means of great self-sacrifice,

energy and business acumen; meanwhile the Janvrins hung on until the

world market improved after 1800. They virtually had Gaspé Bay, with its

excellent harbour and curing beaches (especially at Grande-Grève, the

best beach in the Gaspé district) to themselves, their only competition

being the small business run by McPherson on the south shore of Gaspé

Bay.

These firms dominated the Gaspé fishing industry between 1790 and

1830 except for a few pedlars who sailed along the coasts of Gaspé every

summer touching at each small port and cove. These itinerant traders

were often able to sell goods at prices considerably lower than those

offered by the large companies, but they seldom had any salt and

usually sold their goods for cash only. (Both salt and cash were scarce

in Gaspé.) Some of these independent merchants did take fish, but there

were complaints that they traded alcohol for fish and corrupted the poor

fishermen.51

It was difficult for an entrepreneur to break into the Gaspé fishing

industry which was so firmly controlled by the two large companies. The

first man to successfully break into the monopoly and offer true

competition was John LeBoutillier. He, too, had come from Jersey at an

early age to work for the Robins. About 1830 he established a small

fishing post at Percé. He appears to have received some financial

backing from François Buteau, a Quebec merchant who had been trading

seasonally in Gaspé for 20 years and who participated in the fishing

industry at his seigneury of Sainte-Anne-des-Monts. Starting cautiously

and at first specialising in the export of "la morue de

réfection" to Quebec, they were soon able to expand and by 1836 added

posts at Anse-aux-Griffons and Paspébiac. Buteau apparently left the

firm early, but LeBoutillier was soon joined by his sons and the firm

grew; however, it never reached the proportions of Charles Robin and

Company. In 1850 they were reported to be exporting 20,000 quintals of

fish a year (compared to the 40,000-50,000 quintals exported by the

Robin Company) and by the 1860s they had posts at Gaspé Bay, Percé and

Anse-aux-Griffons.52

About 1838 three brothers who had been working for Charles Robin and

Company began a merchandising and fish exporting business on the

Paspébiac barachois adjacent to the Robins. David, Amy and Edward

LeBoutillier were Jerseymen, but only distantly related to John

LeBoutillier. The LeBoutillier brothers seem to have been the first

Gaspé fishing firm to establish a fishing post on the Labrador coast.

They opened posts at Ile de Bonaventure and Miscou Island as well, but

their headquarters and shipping centre remained at Paspébiac. From there

they were reported, in 1852, to be exporting about 20,000 quintals of

cod.53

The LeBoutilliers showed that competition with the two large firms

was possible and several other people quickly followed their lead. The

Jersey firm of Hamon and LeGros began a fishery at Newport in the early

1830s and the Quebec-based firm of Georges and Ferdinand Boissonault

opened one at Bonaventure. Though this end of Chaleur Bay was not rich

in cod, by 1850 the two brothers had 150 boats in service there, each of

which brought in about 100 quintals a season. Around 1843 William Hyman,

a native of Russia, began a small operation on the Forillon peninsula

which lasted into the 1960s.54

None of these companies fished for whales; that was left to the

specialists — the Boyle family of Gaspé Bay. Von Iffland noted in

1821 that the Boyles had, at L'Anse-aux-Cousins, "des fourneaux avec des

chaudières énormes où ils font bouillir la chair de ces poissons après

l'avoir coupée en morceaux. Des tubes, à ce qu'il m'a paru, transportent

l'huile dans un grand réservoir." By the 1830s the refining operations

had been moved to Penouil where the Boyles and others erected "quelques

chétives baraques; là sont amoncelées des masses de lard de baleine, que

l'on fait fondre dans d'immenses chaudiéres, afin d'en extraire les

matières grasses et huileuses."55

In 1818 the assembly of Lower Canada discussed various problems in

Gaspé and Jean Taschereau spoke at length about the need to get more

Québécois merchants interested in the district because its economy was

dominated by outsiders.56 Of all the Gaspé entrepreneurs

noted above, only François Buteau, the Boissoneault brothers and perhaps

the Boyle family were native to Canada and they were not leaders in

their field.

The majority of the capital and management for the Gaspé fishing

industry came from the Channel Islands because people there were willing

to risk the large initial investment required to become established in

the fishing industry. As important as the capital were the many hard

years they were willing to invest in directing the fisheries. The fate

of two such investors, Frederick Haldimand and Charles Robin, will be

examined to show that the fishing industry dominated not only the lives

of the fishermen, but also the lives of management.

|