|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 23

Gaspé, 1760-1867

by David Lee

Introduction

The peculiar and remote situation of the County of Gaspé, as

similate it in some respects to a separate Colony from Lower Canada,

being divided from the other populous parts of the Province by a

Wilderness of Four hundred miles, without roads, or any other than Water

Communication.

William Fruing

William Fruing, general manager of the Charles Robin and Company

operations at Paspebiac, attributed the "peculiar" situation of the

District of Gaspé to its poor communications with the "populous parts of

the Province."1 In 1828 an average voyage between Gaspé and

the provincial capital, Quebec City, took a week. Marine communications

naturally depended on the weather — the length of time for the trip

varied from less than a week to more than two. From December to May all

shipping ceased and the only contact Gaspé had with the outside world

was by means of the occasional brave traveller going overland. It was a

long time before communications improved and in the interim Gaspé

remained "peculiar and remote," virtually a terra incognita.

Geography and Fisheries

Normally Gaspé was the first land encountered by Europeans travelling

to Canada. Gaspé Bay offered a large, safe harbour which had attracted

European ships as early as the 16th century. After long and stormy

Atlantic voyages many ships headed for its refuge where they could

anchor and rest, repair damage, get fresh water and fuel, and perhaps

hide from enemies. With this amount of marine traffic, one would not

think of Gaspé as separate and unknown in Canada, but few passengers

ever disembarked at Gaspé Bay. After a few days' rest the ships continued

on to the "populous parts of the Province," along the St. Lawrence

River valley.

The cod fisheries of Gaspé were perhaps better known in Europe than

in Canada. The fisheries attracted some European ships to the shores of

Gaspé and eventually a few Europeans settled on these shores, but even

these permanent residents really knew little more than the coastlines

and their settlements were never beyond sight of the sea.

The reason for this ignorance of their own area was, of course, its

topography. As Father Chrétien Le Clercq noted in 1691, Gaspé is a

country full of mountains, woods and rock."2 Even the Indians seldom

ventured far into the interior and no Europeans crossed the width of the

peninsula until 1833. Minerals in the interior were unknown and

unexploitable. The timber industry did not develop until the 19th

century because the rivers were too wild and poor transportation also

prevented the development of an extensive fur trade although

occasionally the settlers travelled a few miles up the rivers to lay

nets to catch the salmon which abounded there. Although some at the

valleys contained fertile soil, agriculture always remained secondary to

fishing.

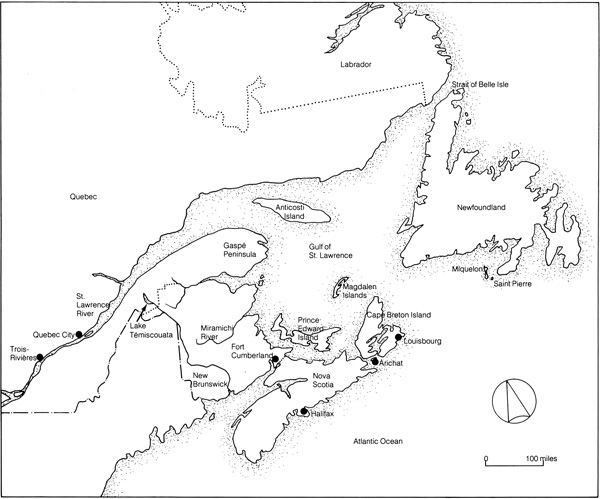

1 The location of the Gaspé Peninsula.

(Map by S. Epps.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

The riches of the Gaspé cod fisheries had attracted Europeans since

the 16th century. Cod are caught in areas of shallow water, known as

"banks," extending from Labrador to Cape Cod; they range from five to

ten pounds on the coastal or near coastal banks and up to 100 pounds on

the offshore banks. Cod feed principally on herring and capelin and in

spring they follow these fish as they migrate from deep water to the

banks where they spawn in summer. Rich in protein, cod has been a

dietary staple in Europe for centuries.

Although the people of Gaspé were largely ignorant of the land, they

knew well the sea and all the nearby cod-fishing banks. There were major

offshore banks near Anticosti Island and Miscou Island as well as the

famous Orphan Bank out in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. More important,

though, were the coastal banks. The richest of these was along the shore

between Cap des Rosiers and Cap d'Espoir; but cod could be found along

the entire shoreline of Gaspé, from Cap Chat and Matane on the St.

Lawrence River to the mouth of the Restigouche River in Chaleur

Bay.

Cod dominated the lives of every Gaspé resident. Every summer day

the fishermen, two or three men to a shallop, would go a mile or two

offshore and fish until their shallops were full. They would then

immediately return to land where the "shore-men would split and

eviscerate the fish, wash them and place them in salt. In the "green"

fishery the cod would remain in salt until it reached its market; in the

"dry" fishery the cod remained in salt for only a few days before it was

taken out to dry in the sun and wind. Some green cod was produced in

Gaspé (especially late in autumn when the weather turned cold and wet),

but Gaspé was more suited to the dry cod industry. Along the shores were

many shingle beaches upon which the smaller Gaspé cod could be laid out

to dry. At night and when it rained the fish were gathered together and

sheltered from the wet. In later years it became more common to erect

flakes of boughs on which the cod could be laid; air could circulate

more freely and hasten the drying process. After a month or so of drying

they were ready to be loaded on ships. If ships were not yet available,

the fish were piled in large mounds and protected from the rain by

branches.

The French exploited the Gaspé cod fisheries for over 150 years and

their value was one of the attractions which drew the English to their

conquest of New France. Cod from Gaspé was an important dietary staple

in France and a valuable source of foreign exchange when exported to

other countries. The Gaspé fisheries contributed perhaps one-fifth of

the dried cod produced by New France.3 The fisheries employed

thousands of men and stimulated the ship-building industry; the French

navy esteemed the fisheries because the experienced seamen they produced

were invaluable in the event of war.

Gaspé to 1758

For a long time the French came to Gaspé to fish only in the summer,

but by the 18th century a few small permanent fishing posts had been

established along the coasts of the peninsula. By the time General James

Wolfe came to ravage the coasts of Gaspé in 1758, there were 500 to 600

permanent residents in these settlements. An equal number of fishermen

came to Gaspé from France (as well as a few from Quebec) to fish in the

summer and then return home in the autumn.

French fishing settlements were normally established at the mouths of

streams where fresh water was available as well as wood for fuel and the

construction of houses, boats and flakes. Other considerations included

sheltered harbours, good beaches exposed to reliable breezes, proximity

to fishing grounds and the length of the fishing season. The waters off

Percé held the richest fisheries and there were good beaches on the

nearby mainland, but Percé had no harbour. Gaspé Bay had excellent

harbours, but fewer cod and a shorter fishing season. Chaleur Bay did

not have fishing grounds as prolific as those of Percé, but its

barachois (lagoons enclosed by triangular sandbars formed by tidal

action) provided splendid harbours and beaches. Fishing shallops and

small schooners could sail through the narrow tickle (or goulet) and

anchor safely in protected water; at high tide ocean-going vessels could

anchor in the roadstead outside the barachois, and all the shore

operations of the fishery could be performed on the sandbar. During the

summer months throughout the 19th century, the fishermen lived in shacks

on the beach; in autumn, when the frantic pace of the fishing operations

declined, they retired to more substantial houses on higher ground

where they were closer to the forest and its wood and

game.4

In the French regime the fishing settlements of Gaspé developed with

virtually no encouragement from government authorities in Quebec or

Versailles. Although Gaspé was nominally under the jurisdiction of the

governor of Québec, he exercised no real authority in this remote area.

Percé in the summer was a wild scene: fishermen from France fought over

the best sites on the beaches, and after a hard day's work on the

fisheries there was much drinking, gambling and fighting. It was also a

convenient place for smugglers and fugitives to contact ships sailing

for Europe.

Several seigneuries were granted in Gaspé, but only the seigneury of

Grand Pabos was ever developed. When the Lefebvre de Bellefeuille family

went to live there permanently, the French authorities were provided the

opportunity to install a Gaspé resident with some local authority.

Georges Lefebvre de Bellefeuille was created sub-délégué de l'intendant

in 1737 though he had little effective power to enforce law and order in

the area. In 1757 a ne'er-do-well, Pierre Revol, was appointed agent of

the governor at Gaspé Bay, but he died the next year, three days before

Wolfe and his men arrived at the bay. Many suggestions had been made to

fortify Gaspé Bay, but defence was another matter the French government

neglected in Gaspé. The settlements and economy of Gaspé developed on

their own without any encouragement from — indeed in the ignorance

of — the French government. The people developed a sense of

independence and, in effect, Gaspé became virtually a colony in itself.

Gaspé after 1758

After Louisbourg fell in 1758, Wolfe visited Gaspé and devastated

the French settlements at Mont-Louis, Gaspé Bay, Pabos and

Grande-Riviere. His men destroyed over 15,000 quintals (hundredweight)

of dried fish, more than 100 houses and over 150 boats. Some of the

population had already fled to Quebec and most of the remainder was

transported to France. A few families, especially from Pabos and

Grande-Rivière, hid in the woods where, for the next few years, they

lived off the land, hunting and fishing. In 1759 and 1760 a number of

Acadians fled northward from the Miramichi and established a settlement

at the mouth of the Restigouche River, near a Micmac village. Quebec

fell to Wolfe in 1759, but the French king still hoped to save New

France in 1760 by sending out a fleet of ships, men and provisions. The

fleet went first to Chaleur Bay where they found the Acadian refugees. A

British fleet followed them up the bay and defeated the French and their

Acadian and Indian allies in July 1760. They also destroyed a large

number of the temporary buildings the Acadians had erected at their

settlement (called Nouvelle-Rochelle) as well as most of the Acadian

sloops and schooners. The British fleet then returned to Louisbourg,

leaving the French on the bay. In the fall the British sent a few ships

back to the Restigouche, received the surrender of the French troops who

had remained there, and sent them back to France.5

After the Conquest some of the original French residents of Gaspé

returned to the sites of their former homes on Chaleur Bay. These people

were skilled in catching and curing cod; it was probably from them that

later arrivals learned the technique. Of the Acadian refugees, some

moved to Quebec and some were subsequently transported to Nova Scotia,

but many remained to settle permanently on Chaleur Bay. Soon after the

Conquest the celebrated riches of the Gaspé fisheries began to attract

English-speaking settlers to the area. A census of 1765, though not

complete, reported a population of between 300 and 325 Europeans, about

one-sixth of them English.6 In 1774 Charles Robin brought 81

Acadians to Gaspé from their exile in France.7 A census of

1777 reported more than 500 Europeans permanently residing in

Gaspé.8 Over the years other groups, the Irish and the

Channel Islanders, appeared and in 1784, 500 to 600 Loyalists arrived.

By 1808 the population had risen to 3,200 people.9 After the

Loyalists came there was little immigration but the population increased

extraordinarily by natural growth. Table 1 shows the growth of the

European population of Gaspé in the early 19th century.10 By

1852 the population had increased to 19,546 and by 1861, to 24,518

people.11

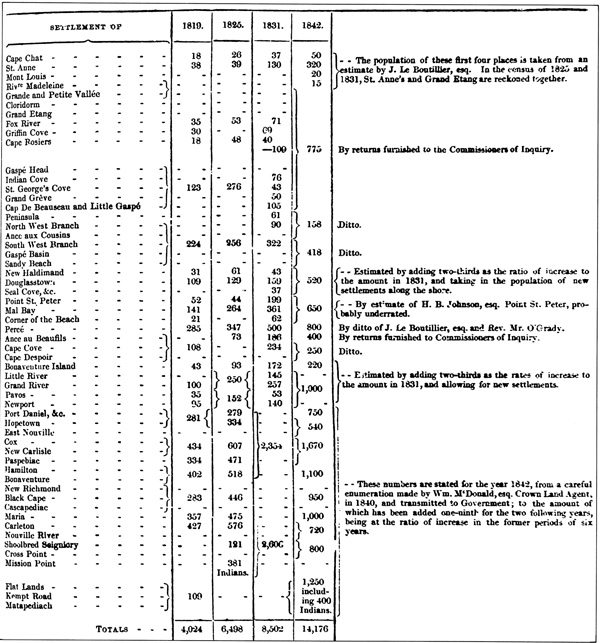

Table 1. "Comparative View of the Population of the District

of Gaspé in the Years 1819, 1825, 1831, and 1842."

(Public Archives Canada, MG11, CO42, Vol.

504, p. 23.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Gaspé had been bypassed, neglected and ignored by the French

authorities in the 17th and 18th centuries and had become virtually a

separate colony unto itself. A similar attitude of neglect was displayed

by the British government after it obtained the sovereignty of Gaspé. As

William Fruing observed, Gaspé came to resemble "in some respects ... a

separate Colony from Lower Canada."12

Because of its rugged topography and remote location, Gaspé was never

truly a part of Quebec or Canada in the period between the Conquest and

Confederation. This study examines three aspects of this period in Gaspé

history: (1) government neglect of Gaspé interests; (2) the predominance

of the fishing industry in the area, and (3) the unintegrated and

diverse population of Gaspé.

|