|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 23

Blockhouses in Canada, 1749-1841: A Comparative Report and Catalogue

by Richard J. Young

Part I: A Comparative Study

Blockhouses and Harbour Defence

Blockhouses played only minor roles in the extensive, sometimes

elaborate fortifications built for the security of harbours such as St.

John's, Newfoundland, Halifax, Saint John, New Brunswick and Kingston.

They were used, for the most part, as temporary expedients for defence

in times of crisis or war, while the plans for permanent works of

fortification for these harbours were endlessly shuffled between the

engineers, the Board of Ordnance and parliament.

The regulations of the Board of Ordnance permitted a local commander

to undertake only temporary, emergency fortifications on his own

authority. Small batteries, blockhouses and redoubts —

inexpensive works which could be built quickly in moments of crisis

— accounted, therefore, for many of the works of defence in these

harbours. Such works were built by different engineers with conflicting

ideas, often on the fragments of earlier plans or on the ruins of

earlier works. In England the prevailing attitude of the government was

that the security of ports in British North America could be achieved

much more cheaply and effectively by maintaining the superiority of the

British fleet than by building permanent land defences. The commander of

a colonial station and his chief engineer may have held contrary

opinions, but the superior wisdom of Whitehall usually prevailed.

The geographical contours, the different uses and varied strategic

importance of each harbour and town determined the nature and history of

the fortifications built in the four harbours mentioned above. The

variation was considerable. Blockhouses were usually advanced posts to

the main point to be defended, and provided defensible barracks which

could occupy a redoubt, support a battery, protect a road, or be joined

by picketing to other blockhouses to defend an extensive tract of land

which could not be regularly fortified.

St. John's, Newfoundland

From the year 1583, when Sir Humphrey Gilbert finally and officially

claimed the harbour for the Elizabethan crown, St. John's became the

main refuge of the British fishing fleet in the North Atlantic. In times

of war, the fishing vessels were convoyed to St. John's in the early

spring, dispersed to favourite fishing waters in summer, and reassembled

in the harbour in October to be convoyed back to Britain. As well, St.

John's became the administrative port for the "admiral" of the fishing

fleet. Although the economics of the English West Country fishing

industry discouraged long-term settlement, seasonal habitation gradually

gave way to a permanent establishment. In the long struggle between

England and France for control of the Newfoundland fisheries during the

first Elizabeth's reign, fortifications were begun for the defence of

the harbour.

Although a small stockaded fort (Fort William) had been built in 1790

for the accommodation of troops, measures for defence of St. John's had,

from the beginning, been concentrated at the harbour's narrow entrance.

The soaring cliffs which formed the small gut at St. John's made the

harbour a natural stronghold. Until early in the 19th century, the

succession of sea-level batteries, chains and towers in this entrance

provided the main defence of the harbour. Little more was needed. A few

guns at the mouth of the harbour made St. John's almost impregnable to

assault from the sea.

The gradually sloping ground at the back of the harbour behind the

town could not be defended, however. Four times the town of St. John's

was attacked and forced to surrender. (It was taken by Le Moyne

d'Iberville in 1696, by Saint-Ovide de Brouillan in 1708, by

D'Haussonville in 1762, and finally by Amherst, who recaptured the fort

in 1762.) Each time, the successful assaults came from the landward

side behind the town. The tiny Fort William was destroyed and rebuilt no

fewer than three times. Several coves and bays to the north and south of

St. John's provided a number of easy landing places for troops. If an

attacking fleet went unobserved, a surprise attack from the land could

not be repulsed.

The British government was unwilling to spend huge amounts of money

to fortify St. John's against a regular siege. As long as the fleet was

considered secure and the small regular garrison housed, a seasonal town

could not justify further expense. After the embarrassment caused to the

British crown by the easy French victory at St. John's in 1762, Captain

William Debbeig was sent out to investigate the harbour defences and to

look for possible alternatives to the existing defences of St. John's.

Debbeig's instructions clearly outlined government opinion of

fortifications in Newfoundland.

The Protecting the Vessels, Seamen, and Fishing Utensils from a

sudden Attack, as has been said above, is the main point. The protection

of the Inhabitants settled on the Island, is neither practicable nor

desirable. The Choice of a secure port where ships can retire to, seems

to be the only means of affording them protection; and Batteries and

Forts, at the same time that they defend the Entrance may afford

security to the Stores. A large Fortress which would require a numberous

Garrison, would afford no protection to the Shipping against a Force

capable of laying Seige to it, and against a lesser force, the Batteries

which are proposed for the Defence of the Entrance of the Harbour alone

would be sufficient... As to the Garrison that can be allowed, their

number must entirely depend on the size of the Works, and that must

again depend on the Situation of the Ground. The less number requisite

to defend the Works, the better; but Two Hundred men, or three Hundred

at the most, if necessary, may be granted.1

Captain Debbeig duly made his recommendations, which were ignored for

almost a decade. During the American Revolution, when Britain was again

forced seriously to reconsider the defences of the port, a strengthening

of the works and the erection of new fortifications were ordered.

Captain Robert Pringle superintended the works, which followed closely

Debbeig's earlier recommendations. New batteries were built at the

harbour mouth, a chain was installed across the gut, and Fort Townshend, an

earthwork, rose above the town behind Fort William.2

In 1793, war between England and revolutionary France again brought

the fortifications of St. John's into focus and under criticism. Colonel

Thomas Skinner, the Commanding Royal Engineer at St. John's, finally

turned the opinion of the government toward considering a citadel.

Neither Fort William nor Fort Townshend adequately covered the town or

harbour. Each fort provided only security for its own garrison —

but even this was an uncertain safety: it had been conceded by all the

engineers ever stationed at St. John's that these forts were commanded

from the ranging hills behind the town. Signal Hill, the north-side

eminence at The Narrows, could, with proper fortification, be made into

a final, safe retreat against a regular siege. It commanded the harbour

but could not completely protect the town. If the British were to keep

Newfoundland, Skinner and all the engineers who followed him argued,

Signal Hill was the point to be fortified.

It was at the back of the highest ridge on Signal Hill that the

British built the only blockhouse for defensive purposes in the history

of St. John's. The blockhouse was begun in 1795 and was intended to be

the focus and high point of the Signal Hill defences. The lower storey

was 30 feet square and built of stone. This storey was considered

bomb-proof and contained space for 150 barrels of powder and other

artillery stores. The upper storey was used as quarters for officers and

artillerymen; it was wooden, and was turned diagonally on the storey

below. The roof was flat and was intended to mount ordnance. Two

batteries, east and west of the blockhouse, were built at the same

time.3

In the two succeeding decades an extensive system of fortification

was built to occupy Signal Hill, but under no systematic plan. The

blockhouse was demolished in 1814 to make way for

a Martello tower — part of an extensive proposal for a

permanent citadel by Captain Elias Walker Durnford, R.E. This tower and most

of the works which Durnford proposed were never built. Two blockhouses

were built later on the hill, but were used mainly as signal towers and

seem to have had no defensive significance.

With this one exception, the absence of blockhouses at St. John's is,

for the most part, explained by the government's reluctance to fortify

the town. The only measures taken for defence at the back of the

harbour were Fort William and Fort Townshend, which were established

solely for the security of the government and regular troops. Wooden

musket-proof blockhouses would have done little to defend the batteries

located in The Narrows. Batteries were established at various times at

the out-harbours and coves near St. John's but, unlike the rest of

Canada, no blockhouses were built to barrack the troops or protect the

batteries at these points.

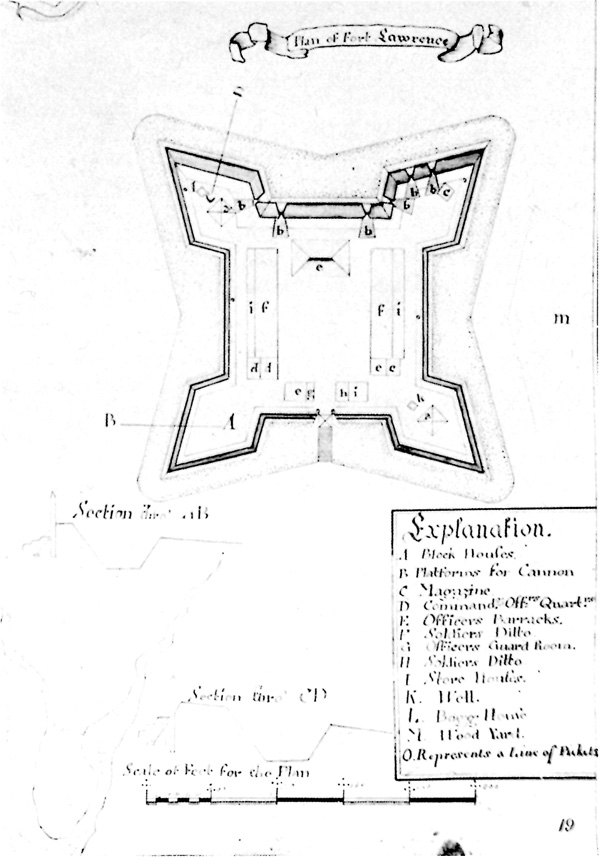

13 Plan of Fort Lawrence, 1755.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

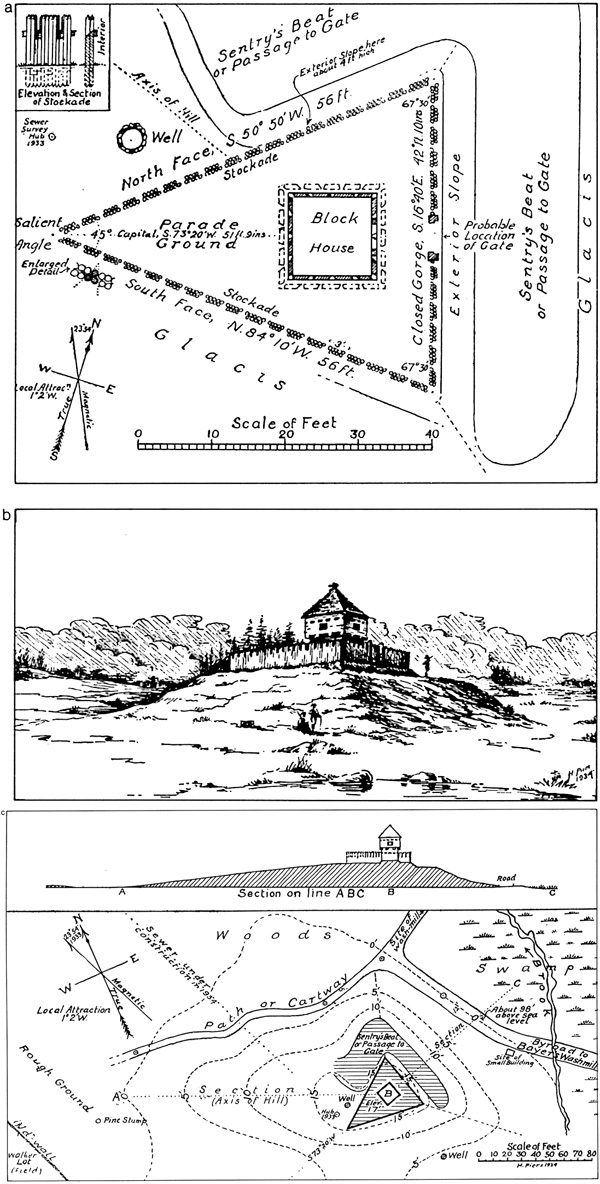

14 The middle peninsula blockhouses at Halifax, 1751, by Harry

Piers; a, plan of the site of the blockhouse and stockade;

b, perspective restoration looking northwest; c, general

contour plan and section of the site.

(Harry Piers, "Old Peninsular Blockhouses and

Road in Halifax, 1751; Their History, Description, and Location,"

Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society, Vol. 22 [1933], pp.

96-153.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Halifax, Nova Scotia

Like St. John's, Halifax was an important naval base from the day it

was founded, but the geographical features of Halifax harbour, unlike

St. John's, provided no easy answers for protection against sea

assaults. The relative vulnerability of the harbour, however, was

balanced against the fact that an attack on Halifax had to be made

directly by sea: no suitable landing place for troops existed short of

St. Margaret's Bay, 25 tortuous miles to the west. Consequently little

attention was ever given to the landward defences at Halifax except in

the very early period. Efforts at fortification were concentrated at

points on each side of the harbour entrance, and on a series of citadels

behind and above the town. The ultimate safety of the harbour rested

with the power of the British navy. Frantic attempts at fortifying

Halifax in times of war alternated with extended periods of total neglect in

times of peace. The 14 blockhouses built in the Halifax defence system

between 1749 and 1808 were temporary buildings erected in

emergencies.

The three peninsular blockhouses described earlier were the first to

be built at Halifax. These blockhouses were constructed early in the

first winter of the settlement in an attempt to seal off the peninsula

from Indian attacks. The rapid growth of the town, however, and the

large garrison stationed there continued to discourage any attempt by

the Indians against the peninsula. The three small blockhouses built to

meet the rumoured emergency of that first winter very soon became

unnecessary defences.

15 Watercolour by Harry Piers of the middle peninsular blockhouse,

Halifax, 1751.

(Public Archvies of Nova Scotia.)

|

16 Watercolour by Miss S.E. Harper of the west blockhouse

at St. Andrews, New Brunswick.

(New Brunswick Museum.)

|

The Naval Yard

In 1762 the rumour that a large French squadron was cruising the

North Atlantic and the subsequent capture of St. John's, Newfoundland,

in July of that year necessitated hurried preparations at Halifax. Work

on Citadel Hill was halted in order to provide men to strengthen the

batteries at the south end of the peninsula. Attention was also given

for the first time to the defences of the naval yard. Building of the

dockyard had been started in 1759, and its site, north of the town, was

a bad choice from the point of view of defence. Major John Henry

Bastide, the Commanding Royal Engineer at Halifax, had informed General

Amherst a year earlier that "the Naval Yard [could] not possibly be

brought within the line of Defense proposed for the Town."4

The naval yard's security lay in the fact that an enemy could attack it

only after passing the fortifications farther out the harbour. In the

emergency of 1762 the sole measure taken for the defence of the

dockyard and the stores deposited there was the entrenchment of Maugher

blockhouse.5 This blockhouse — placed on a small hill

above the dockyard — had been built before the crisis.

Work on the Halifax fortifications was completely suspended with the

coming of peace in 1763. The problem of the naval yard defences was

left without attention until the American Revolution. By that time, a

great quantity and variety of naval stores for the north Atlantic fleet

was deposited at the Halifax dock yard. Concern about the safety of

these stores was responsible for the government's taking more temporary

measures for the defence of the yard in 1775. Lord Suffolk wrote to

Governor James Legge on the subject,

The ruinous State of the Fortifications at Halifax had been the

Subject of frequent consideration, but as the ablest Engineers who have

been consulted upon it have concurred in opinion that the Harbour is too

extensive and the advantages of Attack too many to admit of any regular

effectual plan; all Ideas of that kind have been laid aside.

It is judged proper however upon the present occasion to direct

that some Works upon a temporary plan of defence should be constructed

for the Security of the King's Naval Yard, and the Board of Ordnance

will by this conveyance send out orders to that Effect to the principal

Engineer at Halifax.6

A month later, in November, Legge reported to Dartmouth that Captain

William Spry, R.E., was employed "in preparing some Temporary Works for

the security of the [naval] Yard."7 In September 1776 Spry

advised General Eyre Massey that three bastions behind the naval yard

were finished, and a double stockade with loopholes completely

surrounded the yard. Two blockhouses had been constructed outside the

north and south walls of the enclosure. Spry also reported that the

blockhouses intended for guardrooms to the bastions and as secondary

defenses of the lines were "ready to raise."8

Fort Needham, north of the naval yard, was also begun in 1776. It was

an earthen redoubt constructed on Pedley's Hill, and was intended to

cover both The Narrows and the naval yard. It contained barracks for 50

men. A blockhouse called Fort Coote was built at the northwest end of

the naval yard on a projecting point. It covered the naval yard and

protected the approach to Fort Needham. Three 18-pounders were mounted

at Fort Coote.9

None of these defences for the naval yard was ever tested, but

Captain James Straton, R.E., wrestling with the same problem in 1796,

criticized the earlier temporary works.

As for putting the Dock Yard, hors d'Insult — from an Enemy

beseiging Citadel Hill Work — it is impossible — not

even the strongest Fortress that could be erected on Needham Hill, would

prevent it — much less the two little Redoubts that were there, and

the three detached Bastions open in the Gorges, and connected only by a

common Picketting, the whole lying on the side of a Hill Just above the

Dock Yard, whose summit effectually commands those Works — and

everything near it. They never could have resisted a spirited

Attack.10

Two other blockhouses were built at Halifax during the Revolution. A

large octagonal blockhouse three storeys high, 50 feet in diameter and

designed to barrack 200 men was constructed in 1776; it was built in a

large square redoubt on the summit of Citadel Hill.11 The

hill's defences consisted, at that time, of a maze of batteries and

irregular earthworks begun by Bastide in 1761 and elaborated by Spry

during the Revolution. The earthen redoubt which occupied the top of

the hill mounted 14 24-pounders in its embrasures. The blockhouse was

built in the centre of the square. Eight six-pounders mounted on the

building's second storey could be fired through portholes in all eight

faces of the octagonal blockhouse, and effectively covered the guns of

the redoubt.

Fort Massey, a square earthen redoubt on a small hill south of the

citadel at the junction of present-day South and Queen streets, was also

built in 1776. Spry reported to Massey on 4 September 1776 that "two 24

pounders [are] mounted, the post defencible, and will be finished in ten

days."12 This redoubt covered the southern approach to the

citadel and protected green-bank and barbette batteries situated below

it. A blockhouse designed to accommodate 39 men was built in the

southeast corner of the redoubt. Two barracks and a small magazine were also

included in the work.13

The fortifications at Halifax were again permitted to fall into

disrepair after the end of the American Revolution. The next crisis to

erupt was the war between England and France in 1793. His Royal

Highness, Edward, Duke of Kent, had taken command of the forces in Nova

Scotia in 1792. The war with France provided Edward with the excuse he

needed to proceed with his plans for reshaping the defences at Halifax.

In spite of the Board of Ordnance's attempts to obstruct him, Edward

managed, during his command at Halifax, to carry out an extensive revision

and strengthening of the Halifax fortifications. Among his works were

two blockhouses.

In 1795 Edward ordered a blockhouse to be built in the rear of the

York Redoubt. Construction of this eight-gun battery had been started

the year before to guard the western entrance to the harbour. The

blockhouse was intended as a keep for the battery and for the small

powder magazine nearby. Artillerymen stationed at the battery were

lodged in the blockhouse, and its second storey mounted two small

carronades.14

Another blockhouse 40 feet square was built inside Edward's star fort

on Georges Island, and provided barracks for the regular troops

stationed on the island. The blockhouse was designed to lodge 40

men.15 Its roof was left flat in order to mount additional

ordnance within the fort.

The renewed war with France in 1807-08 occasioned the building

of more defence works at Halifax. The works which the Duke of Kent had

built a decade earlier were patched up, and two new works were begun at

the north end of the peninsula. Fort Needham had fallen into ruins since

the American Revolution, and it was completely rebuilt in 1808. A

battery was constructed to protect The Narrows at the same time. Midway

between the refurbished fort and the new battery, a blockhouse was built

in 1808. It stood slightly to the north of Fort Needham, and mounted two

12-pounders in its second storey. It also contained a small magazine.

This blockhouse covered the battery and protected the northern

approaches to Fort Needham.16 Another blockhouse was

constructed inside Fort Needham redoubt in order to replace the

barracks, which were out of repair. General Hunter had received

approval to erect a stone tower in the fort, but the shortage of time

and manpower forced him to build the blockhouse as a temporary

measure.

Repeated proposals had been made since 1760 to provide once more for

the defence of the narrow neck of the peninsula. The recommendations

made usually suggested a series of redoubts with blockhouses and

batteries en barbette to occupy the high points of land between the

Northwest Arm and Bedford Basin. Fort McAlpine, which General Hunter

ordered built in 1808, was the only defence ever erected for this area.

It was a large pentagonal redoubt with a two-storey pentagonal

blockhouse inside which was begun in the summer of 1808. The work was

intended to cover the approach to Halifax from the Bedford road, and to

prevent troops from landing on the north shore of the

peninsula.17 The three blockhouses built in 1808 were the

last to be erected in Halifax.

17 Watercolour by Capt. Reid of the east

blockhouse at St. Andrews, New Brunswick.

(New Brunswick Museum.)

|

18 A sketch of the Liverpool blockhouse.

(Public Archives of Nova Scotia.)

|

Saint John, New Brunswick

The harbour and town of Saint John was a post of only minor

importance to the British. But by the time of the American Revolution

the supply of timber from the Saint John River area was becoming

absolutely necessary for providing masts for the British navy; moreover

the river was the only communication route between Quebec and Halifax in

time of war. The troublesome raids made by Ethan Allen and his company

of rangers into New Brunswick and Nova Scotia prompted General Massey to

write to General Howe in 1777 asking for reinforcements to establish a

post at the mouth of the Saint John River, a request which Howe

approved. In November 1777, Massey sent Captain Shudholme with 50 men

and two frigates to establish the post. With them were a small

blockhouse (prefabricated in Halifax) and four six-pounders to be

mounted in it, to facilitate the troops' task.18 The

blockhouse was erected, palisades dug in, and an abatis thrown up before

winter set in. A barracks for 100 men was added during the winter. The

post was named Fort Howe. It was situated on a high ridge at the

northern extremity of the harbour, which it commanded; immediately

across the harbour from it were the ruins of Fort Frederick. Another

blockhouse was built the next year, at the other end of the high ridge

overlooking the Saint John River.19

In the crisis of 1793, Governor Thomas Carleton thought it proper and

necessary to build some temporary defences against sudden attack.

Dorchester Battery was erected at the southern end of the Saint John

peninsula. Behind it, a 20-foot-square blockhouse was built to protect

the new work. The blockhouse mounted four four-pounders in the second

storey. Mortar Battery, Graveyard Battery and Prince Edward Battery

were built in the same year. Carleton informed Dundas that he had

undertaken these works on his own authority, but that "by the voluntary

assistance of the Inhabitants, I was Enabled to execute [the works]

without incurring any expence to Government."20

Not until the War of 1812 were any further measures undertaken to

defend Saint John. With the outbreak of the war, attempts were made to

put the town and harbour into a state of defence sufficient to repulse

any small, sudden American attacks. If there was ever a large regular

siege, the troops at Saint John were to embark in a flotilla of boats

and retreat up the Saint John River, which could be easily defended

against a pursuing army.

The fortifications built at Saint John during the War of 1812 were

concentrated on the peninsula where the town stood and along the western

shore of the harbour. (The eastern side was considered indefensible.)

The British strategy was that, if the harbour could be adequately

covered by the guns of the peninsula, the western shore and Partridge

Island, then the enemy could not land on the eastern side. If a hostile

fleet could be kept out of the harbour, there was no suitable landing

place closer than 50 miles to the east.21

The line of defence began with Dorchester Battery and blockhouse,

which were located on the southwestern tip of the peninsula. The

battery and blockhouse were built in 1793 and were strengthened during

the War of 1812. In 1815 the battery mounted two 24-pounders on

traversing platforms. The blockhouse, which was 20 feet square in the

lower storey, stood immediately in the rear of the battery. The

blockhouse's upper storey mounted two four-pounders to cover the guns in

front and to prevent an assault by land in the rear.22

Mortar Battery was located 211 yards west of the Dorchester

emplacement. In 1811 this battery mounted three 24-pounders on

traversing platforms, two eight-inch mortars and one eight-inch

howitzer.23 The battery was a semicircular earthwork which

was intended to cover the entrance to the inner harbour.

Graveyard Battery was located 150 yards north of Mortar Battery. It

was a semicircular work which mounted three 24-pounders on traversing

platforms24 and commanded the inner harbour. It had no

blockhouse.

About a quarter of a mile from the Graveyard Battery guns was a small

circular barbette work called Prince Edward Battery. The five

18-pounders mounted there commanded the inner harbour.25 The

work was situated near water level.

At the back of the town, on a hill commanding the main road into the

settlement from the interior, Johnston's battery and blockhouse were

built. This work was begun in 1811 and was completed during the war. The

battery mounted two nine-pounders on wooden platforms. The second

storey of the blockhouse contained two four-pounders.26

At the northern end of the harbour, at the base of Fort Howe hill,

stood the stone powder magazine capable of containing 750 barrels of

powder. On the hill above the magazine, Fort Howe, the small stockaded

work built in 1777, lay in near ruin. The rotten stockades and four

six-pounders in the blockhouse provided a focal point for the defence of

the town and magazine below.27 Slightly to the west and rear

of Fort Howe stood the blockhouse built in 1778. This position

commanded Fort Howe and the mouth of the Saint John

River.28

The fortifications defending the western shore of the harbour began

with Fort Frederick. This fort, which had been established in 1758 by

Colonel Robert Monckton, was in almost total decay. The fort stood at

water level, on a small point of land near the mouth of the river

directly across the harbour from the town and Fort Howe. In July 1812,

Captain McLaughlan, the resident Royal Engineer at Saint John, decided

that the fort should be reconstructed. He believed that guns situated at

this point would provide a good extra defence of the inner harbour and

the town, and would support the batteries on the opposite shore. If an

enemy succeeded in taking Fort Frederick, he could not turn the guns

against the town; the fort was commanded by the heights of Fort

Howe.29 Nicolls, the Commanding Royal Engineer at Halifax,

could see little sense in spending money to rebuild a fort which was

commanded on all sides.30 However, Major General George

Smith, the commander of the New Brunswick forces, instructed McLaughlan

to proceed with his plans for reconstructing Fort Frederick and to begin

the one-storey blockhouse the latter recommended be built

there.31

A blockhouse called Fort Drummond was begun in July 1812. It was

built 1,400 yards along the western shore from Fort Frederick and was

identical to Dorchester Battery blockhouse. It mounted one four-pounder

and one six-pounder on wooden carriages in the upper

storey.32 The ammunition for these guns was stored at Fort

Frederick. The Drummond blockhouse stood on a hill which commanded the

road to Musquash. If an enemy were to land in Magaguadavic Bay, he would

have to pass the work in an advance on the town.

Carleton Tower, the first Martello tower to be built at Saint John,

was begun in July 1814. The tower stood on a hill 200 yards behind

Drummond blockhouse and commanded both the blockhouse and the road to

Musquash as well as the western side of the harbour. Three four-pounders

were mounted in the second floor of the tower and two long 24-pounders

were mounted on its top.33

Partridge Island, at the southwest end of Saint John Harbour, was the

final and most important defence on the western side. Late in 1812, the

lighthouse on the island was converted to a musket-proof barracks for 60

men. The level ground on which the lighthouse stood was enclosed with an

earthen parapet 5.5 feet high. Six 24-pounders mounted behind the

parapet34 commanded both the eastern and western channels of

the harbour. In November 1812, McLaughlan began a blockhouse in the

opposite quarter of the parapet curve from the lighthouse.35

This blockhouse was built to provide quarters for the officers stationed

on the island, and a cookhouse for the men lodged in the lighthouse.

The seven blockhouses described above were the only ones constructed

at Saint John.

19 Blockhouse on Windmill Hill, Lunenburg.

(Public Archives of Nova Scotia.)

|

20 Map by Lt. Pooley, RE, of Liverpool

Harbour, 1820.

(Public Archives of Nova Scotia.)

|

Kingston, Ontario

The necessity of establishing an alternative post at the head of the

St. Lawrence River developed in 1794, when Britain finally agreed to

withdraw her troops from those western posts which lay, it was

determined, in American territory. The post at Carleton Island, which

Twiss had begun in 1778 and which had served as the naval depot for

Lake Ontario and as the transshipment point for supplies to the western

posts, had to be abandoned. Despite some serious objections about

shallow water and the problems of fortifying the place, the British

chose as their alternative Haldimand's Cove, near Kingston. Approval of

the site and authorization to fortify it came from England in 1794. The

Duke of Portland wrote to Dorchester,

should Haldiman's Cove, near Kingston, be found to be better

adapted than any other place, for the immediate purpose of a Military

Post, and for connecting the necessary Communication and Carriage of

Stores etc. between Lower and Upper Canada, your Lordship will of course

fortify it with that view.36

The problem of strengthening the cove to protect the naval depot

proved to be a formidable one. The high ground at Point Henry could not

be occupied as a citadel without an elaborate and expensive system of

fortification. The rising ground on the west side of Kingston harbour

behind the town commanded the harbour, Point Frederick, Navy Bay and the

dockyard. No single system of defence could occupy the whole area. In

the absence of any simple, inexpensive solution to the problem of

defending Kingston, the British relied on continuing peace with the

United States and ignored the question of the harbour's fortifications.

A report on the state of the fortified military posts in Upper Canada,

prepared by Lieutenant Colonel Bruyeres for Prevost in August 1811, did

not mention Kingston.37

Sir George Prevost was aware of the undefended state of Kingston, and

fully realized that an American attack on the post would cut

communications between Upper and Lower Canada and deprive the British of

the naval resources of Lake Ontario.38 Several times in the

first year of the War of 1812, Prevost considered moving the naval

stores to York in order to get them away from the American frontier; but

the need for a strong post at the head of the line of navigation of the

St. Lawrence and the momentum of the war delayed his decision.

In the meantime, Kingston had become established and would have

proved difficult to move. The naval depot, dockyard and shipbuilding

yards remained where they were. The post's importance increased as the

war proceeded. The garrison was increased considerably in the summer and

fall of 1812, and temporary works for the harbour's defence were begun.

During the war, extensive work was undertaken at Point Henry for the

protection of the naval yard. A series of batteries and blockhouses was

erected at various other points in an attempt to protect the town and

harbour. These works were all temporary ones, intended to take the best

advantage of the ground that time allowed.

In the first months of the war, a battery was begun on Point

Frederick to protect the entrances to Kingston harbour and Navy Bay. A

small blockhouse was constructed behind the battery in order to cover

the work and to provide barracks for the artillerymen. When Lieutenant

Colonel Bruyeres visited Kingston in December 1812, he recommended that

another blockhouse be built on Point Frederick. This blockhouse was to

be much larger than the one supporting the battery: 48 feet square in

the lower storey, and capable of barracking 160 men in hammocks.

Bruyeres hoped that this blockhouse would provide additional protection

for the dockyard.39 Work on the blockhouse began in the

spring of 1813. It was located where the Martello tower on Point

Frederick now stands.

To protect the outer channels of Kingston harbour, a small blockhouse

and single-gun battery were established on Snake Island in 1813. The

island is about four miles southwest of the mouth of the

harbour.40 Work also began in 1813 on the defences for the

western side of the harbour and the defence of the high ground behind

the town. The object of the batteries and blockhouses built there was to

prevent an enemy landing on the western shore near the town. In

addition, if the Americans could have occupied the rising ground behind

the town, their cannon would have commanded the entire area, except Fort

Henry. However, the ground was too extensive and time

was too short to prepare anything but a series of small works

connected by a line of palisades.41

The defences on the western side of the harbour began at Murney's

Point where a redoubt (consisting of an earthwork battery with

blockhouse en barbette) was constructed in 1813.42 About midway between

Murney's Redoubt and the battery on Mississauga Point, a small

blockhouse was built on the water's edge to protect the end of the line

of picketing behind the town.43 On Mississauga Point, a

four-gun battery co-operated with the battery at Point Frederick to

defend the entrance to the inner harbour. Behind Mississauga Point, on

rising ground which commanded the battery, blockhouse no. 1 was built.

Blockhouse no. 2 was erected on a triangular piece of land at the corner

of Grass and School streets. This work was the second in the line of

palisades rising behind the town. Blockhouse no. 3 was the next work in

the line. Here the picketing was formed into a bastion and the

blockhouse stood in the gorge.44 Midway between this work and

blockhouse no. 4, a redan was formed in the palisading and a line

barracks established. Blockhouse no. 4 was situated on a hill

overlooking the main road entering Kingston from York. The picketing at

this point was formed into a bastion with the blockhouse inside.

Blockhouse no. 5 commanded the main road out of Kingston toward

Gananoque, and was the last post in the line. The picketing was formed into

a bastion around the blockhouse, and then continued sharply down the

hill to the water's edge.45

Since all the blockhouses built in this line of picketing were

erected at the same time and for the same general reasons, it may be

safe to assume that they were very similar to each other, if not

identical. They were all intended primarily as defensible barracks.

Blockhouse no. 5 measured 30 feet square in the lower storey, and was

reported to be capable of containing 45 men on iron

bedsteads.46 Blockhouse no. 2 was described as being similar

to no. 5.47 The only visual evidence available is a painting of an "old

blockhouse at Kingston"; the blockhouse is not identified (see

Fig. 39) but is probably no. 5.

The ten blockhouses built at Kingston in the War of 1812 were the

only ones ever erected there.

|