Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 23

Blockhouses in Canada, 1749-1841: A Comparative Report and Catalogue

by Richard J. Young

Part I: A Comparative Study

Seven Blockhouses: A Comparison of their Construction Details

This chapter is intended as a broad introductory survey of technical

details of seven blockhouses for which there is the most construction

information. These seven examples cover the whole period of blockhouse

construction in Canada. They also represent a wide range of shapes,

sizes, functions and defensive situations. The seven blockhouses to be

compared are Fort Edward blockhouse, Windsor, Nova Scotia; Fort St.

Joseph blockhouse, St. Joseph Island, Lake Huron; St. Andrews

blockhouse (west blockhouse), St. Andrews, New Brunswick; the octagonal

blockhouse at Coteau-du-Lac, Quebec; The Narrows blockhouse on the

Rideau Canal, Ontario; Fort Wellington blockhouse, Prescott, Ontario,

and Madawaska blockhouse, near Edmunston, New Brunswick.

Historical Background

Fort Edward blockhouse, built in 1750 by Colonel Charles Lawrence on

a rise of land near the junction of the Avon and St. Croix rivers, stood

just within the main gate of a small stockaded fort. It survives as the

oldest blockhouse in Canada.

Construction of Fort St. Joseph blockhouse was started in 1797; it

was built after a design by Gother Mann, and stood in the centre of a

square palisaded fort with bastions at all four corners. The whole fort

was situated on the crest of the highest ground on the island and

overlooked the south channel of the St. Mary's River.

St. Andrews blockhouse (west blockhouse) was built by the inhabitants

of St. Andrews in 1812. It stood on a point of land at the western

extremity of St. Andrews harbour. The blockhouse was built to support a

battery raised a few months earlier to protect the town against American

privateers.

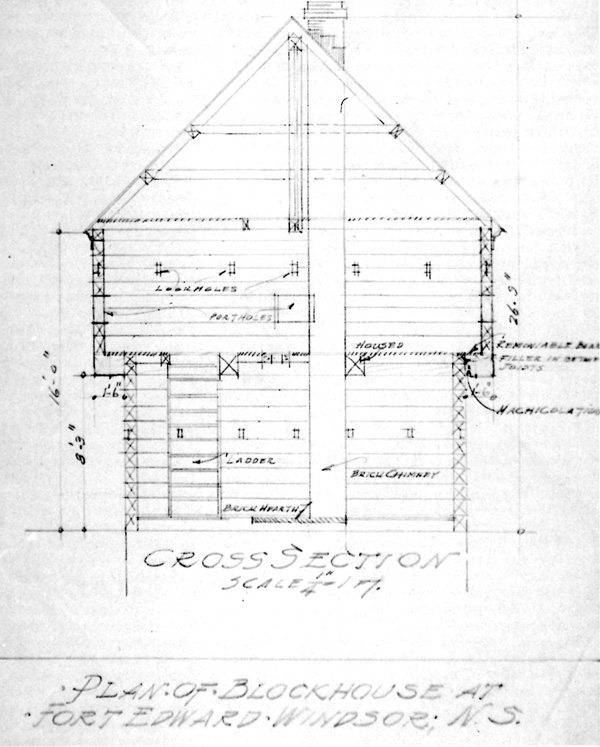

1 Cross-section of Fort Edward blockhouse by Harry Piers.

(Public Archives of Nova Scotia.)

|

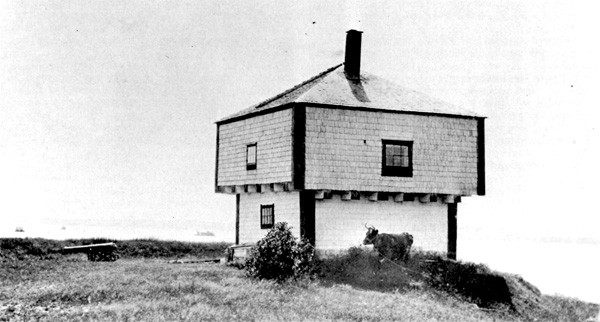

2 South elevation of Fort Edward blockhouse by Harry Piers.

(Public Archives of Nova Scotia.)

|

The octagonal blockhouse at Coteau-du-Lac, built in 1814 on a

triangular piece of land bordered on two sides by the St. Lawrence

River and on the third by the canal which bypasses the Coteau rapids,

was supported on the landward side by a ditch, palisades, redans and two

other blockhouses. The sides of the triangle were defended by picketing

and earth works and a battery was raised at the point.

The Narrows blockhouse, which was built in 1831-32 as one of a

series of fortifications protecting the Rideau canal, was located 70

feet south of lock no. 35 on the man-made causeway at the narrowest

point in Rideau Lake, the top water level of the canal.

Fort Wellington blockhouse, built in 1838-39, was the largest

and most elaborate blockhouse attempted in Canada. It stood in the

middle of a large, strong earthen redoubt beside the St. Lawrence

River.

The Madawaska blockhouse was built in 1841 at the confluence of the

Saint John and Madawaska rivers. Situated on a rise of land due east of

Little Falls on the Madawaska, it was built as a border post primarily

to protect the portage route around the falls.

It is clear from the construction details available for these

blockhouses that a certain sophistication of building techniques took

place with the passage of time. Blockhouses grew bigger, were more

solidly built and more carefully planned, especially after the War of

1812. An important consideration in any attempt to see an evolution in

blockhouse construction over this period is the element of planning.

Those blockhouses which were built in peace time, or were considered

important enough to be designed by an engineer, or were built when

adequate time and money were available, naturally showed the effects of

such considerations. But the majority of the 200-odd blockhouses

erected in Canada were built to fill an immediate need. They were

hastily constructed for very temporary purposes with a minimum of time,

labour and money. Such blockhouses were closer to the rude American

origins of the structure. Few records and fewer examples of this type

survive. The blockhouse built on the Madawaska River in 1841 was one of

the last to be erected, and it was also one of the most carefully

planned. If any blockhouse could be considered to represent an ideal, it

would be this one. Its basement had stone walls three feet thick. Two

partition walls two feet thick divided this first floor into two rooms

which served as magazine and artillery stores, and a commissariat store

with provisions for 100 men. The two upper storeys were composed of pine

logs hewn to 15 inches square, dovetailed together at the ends and

secured with hardwood dowels. The top storey was turned diagonally on

the one below. The middle storey contained 24 woodenberths and was used

primarily as a barracks. The top storey had curbs and blockings for

traversing guns immediately behind each of the four port holes. It was a

well-planned and carefully built post. If lightning had not struck it in

1855, it might stand today as the best example of a blockhouse in

Canada, and one of the most sophisticated blockhouses built in North

America.

Some 82 years earlier, in 1759, Major Patrick Mackellar, an engineer

stationed at Halifax, sent a proposal to the Board of Ordnance for

blockhouses to be built at Halifax. If Mackellar's proposals had been

accepted, his blockhouses would have

been identical to the Madawaska blockhouse, belying an evolutionary

theory of blockhouse construction.

The posts of Dartmouth Fort Sackville and across the Isthmus I

think might be much more secure with good Blockhouses than they are at

present, especially for small parties, they would be better habitations,

more Tenable and with a few annual Repairs, infinitely more durable.

They should be built with the lower storey of masonry or even drystone

if good. This Storey to be planned into small Magazines for provisions

and powder and to be sunk in the ground with a Ditch and palisades round

it, the two upper Storys to be of Logs Clap-boarded and Roofed as Houses

are with a Stack & Chimney in the middle. The uppermost story to

Lay Diagonally upon the middle one, and to project two or three feet

over with a Machicouli in the projection, to Fire into the Ditch, and

upon the Angles below.1

Mackellar's proposal, even though it was never carried out, is good

evidence that, even at the time of the early English settlement of Nova

Scotia, engineers at least were aware of the utility of blockhouses and

had clearly defined ideas about how to build good ones.

Form

The fact that engineers were not always permitted to build as they

wanted or thought best did not alter the fact that blockhouses

continued to be extensively used. There was, in the minds of engineers,

most military men and local colonists, a fairly well-defined concept of

what a blockhouse was and how it could be built. This concept was

derived from the American colonial experience and was transferred to

Nova Scotia and eventually to all of Canada by American emigrants and

the British Army. In North America, blockhouses were usually

distinguished by the following form: a single structure, two storeys

high with an overhanging second storey, loopholes and portholes for

ordnance, and machicolation in the overhang to permit defenders to direct a

downward fire. It was this characteristic form which most blockhouses

shared, with occasional modifications in shape, size and structural

components, because of the idiosyncracies of individual builders and

the demands of each local situation.2

Palisades

The first, fundamental defence of the blockhouse, whether it stood

alone or in a larger defence system, was the palisading which surrounded

it. Originally it was the palisades which determined that blockhouses

had second storeys. The picketing which formed a palisade was usually

composed of cedar posts

10 to 14 feet long, pointed sharply at the top. A trench was dug into

the ground below frost level and the pickets lined into it, sometimes in

double rows. Wooden stringers attached to the pickets by nails or pegs

stabilized and strengthened the line. Loopholes were cut through the

picketing, and occasionally platforms were constructed so defenders

could fire over the top of the pickets. Ditches were dug outside the

palisade to present an even more imposing obstacle to those attackers

who might have succeeded in reaching them.

The Fort Edward blockhouse stood within a stockaded fort. The

palisades, in this case, described the perimeter of the fort — a

regular square 85 yards on each face, with bastions in the four corners.

A ditch surrounded the picketing.

The Fort St. Joseph blockhouse also stood within a stockaded fort, a

square with bastions in the corners. Platforms were built inside the

bastions to mount cannon. A ditch surrounded the palisades, as in Fort

Edward.

The St. Andrews blockhouse had a tall line of palisades connecting

the blockhouse with the extremities of the breastwork, thus forming a

sort of redan.

The octagonal blockhouse at Coteau-du-Lac stood on a triangular

piece of land bordered on two sides by the St. Lawrence River and on the

third by the Coteau canal. The northwest side of this triangle, facing

the river, was picketed as far as the battery which stood on the

point.

Documentary evidence would suggest that there was no picketing at

The Narrows blockhouse.

The Fort Wellington blockhouse stood in the centre of a strong

redoubt built to withstand artillery fire. The palisades ran along the

top of the high earthen ramparts; but palisading was of only secondary

importance in the planning of this formidable redoubt.

There is no documentary evidence of palisades at the Madawaska

blockhouse.

Walls

The walls of blockhouses were almost invariably built of hewn square

timbers laid horizontally on each other. It was this thickness of wood

which proved a relative security against musket balls and arrows. Long

hardwood dowels or "tree nails" were pierced through adjoining logs at

regular intervals to add strength. Small crevices between the timbers

were caulked with a variety of materials. The interior walls were

sometimes plastered, especially if any of the rooms inside were being

used as barracks. The exterior walls were either clapboarded or shingled

to prevent the rapid deterioration of the square timbers. If the

walls were not covered at the time the blockhouse was initially

built, they were usually covered when time or money became

available.

Those blockhouses along the Rideau canal which were built with stone

lower storeys, the Fort Wellington blockhouse which was built entirely

of masonry, except for the wooden gallery which ran along the outside of

the third storey, and the Madawaska blockhouse, were exceptions in that

they did not have square timber walls. These blockhouses were built in

times of peace and were intended to be permanent fortifications;

therefore more care was taken with their design and construction.

The walls of the Fort Edward blockhouse were pine square timbers,

nine inches high and six inches thick, laid horizontally. The blockhouse

was a relatively small one measuring 18 feet square in the lower storey.

The fact that it was prefabricated in Halifax and carried overland to

its destination may, perhaps, account for the relative lightness of the

timbers. All the blockhouses used in the British conquest of Acadia

were prefabricated like this one and carried by the troops to their

respective posts. Smallness and lightness would have been an important

consideration in the design of these buildings.

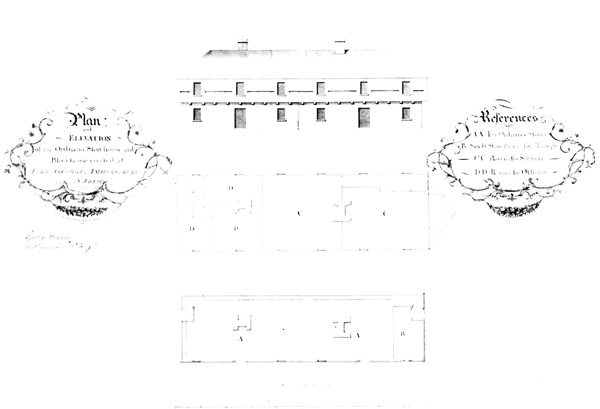

The walls of the Fort St. Joseph blockhouse were of hewn square

timbers approximately 14 inches thick. This blockhouse and others built

to the same specifications (at Amherstburg and Fort George) were

intended primarily as defensible barracks and were very large — 26

feet by 96 feet. Single timbers of that length were, of course,

unmanageable, and so logs of different lengths were married at irregular

intervals. The internal arrangement of rooms and framing provided

much-needed lateral support in these structures. Cedar shingles covered

the exterior of the St. Joseph blockhouse, but were later replaced by

sheet iron as fire prevention.

The walls of the St. Andrews blockhouse were hewn timbers 12 inches

square. The exterior was covered with cedar shingles. This blockhouse

measured 18 feet 6 inches square in the lower storey.

The walls of the octagonal blockhouse at Coteau-du-Lac were of square

timbers, laid horizontally on an octagonal plan.

The lower storey of The Narrows blockhouse was of stone masonry 30

inches thick and 10 feet high. Munitions were stored on this floor,

which accounts for the thickness of the walls. The blockhouse was

square, 24 feet on a side in the lower storey (exterior measurement).

The second storey was built of hewn cedar logs 15 inches square.

The walls of Fort Wellington blockhouse were entirely of grey stone,

hammer dressed. The lower two storeys had walls four feet thick; those

of the third storey were two feet thick. The exterior measurement at the

base of the blockhouse was 50 feet on a side.

The Madawaska blockhouse was three storeys high. The foundation

rested on bedrock, so the basement (which was 7 feet high) was exposed.

The walls of the basement storey were stone, three feet thick. The two

upper storeys were of pine logs hewn 15 inches square, and were secured

by strong hardwood dowels two feet long placed every three feet. The

exterior of the first floor of the blockhouse measured 30 feet

square.

Cornering

The knowledge of a variety of cornering techniques was integral to

the development of horizontal log construction in the early American

colonial period. In Canada there is little variation in such techniques

in those blockhouses still extant. Only two cases seem to have deviated

from the predominant dovetailing method of cornering.

At Fort Edward blockhouse, the earliest for which there is any

information, the timbers were simply halved at the ends and nailed

together. This blockhouse and a number of early blockhouses built in

Nova Scotia were prefabricated in Halifax and shipped with the troops as

they established posts. Either the French (whom Governor Cornwallis

employed to square the timber) were unfamiliar with the sophisticated

methods of dovetailing or — more likely — it was thought that

simply halving the ends of the timbers would facilitate the erection of

the blockhouses when they reached their destinations.

The only other case where dovetailing seems not to have been used was

the octagonal blockhouse at Coteau-du-Lac. Here, Red River frame

construction may have been used: the logs were laid horizontally but

were mortised to vertical posts at the corners. This type of frame was

used extensively in western Canada; the best example is the bastion

blockhouse at Nanaimo, British Columbia.

Those blockhouses which had stone walls, of course, followed the

whims and training of the professional masons who built them.

3 Photograph of west blockhouse at St. Andrews, New Brunswick.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

4 Plan and elevation by Gother Mann of ordnance blockhouse

and storehouse erected at Fort George, Amherstburg and St.

Joseph Island in 1796.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Overhang and Machicolation

Overhang and machicolation were archaic defence features, but ones

which gave the blockhouse its distinctive form. The device of

machicolation was a simple one derived from mediaeval fortification

techniques, and made a good deal of sense in the early

days of Indian warfare. Holes were cut through the floor of the

overhanging upper storey so the defenders could direct a downward (or

machicoulis) fire on an enemy who had breached the palisades and reached

the blockhouse. The second storey thus provided a place of final

retreat; it could conceivably have meant the difference between a

successful and an unsuccessful defence of the post.

The second storey itself was an important feature of the blockhouse's

defence. Because the second storey stood higher than the palisades, a

garrison armed with muskets and a small amount of ordnance could direct

a formidable fire in all directions. In some blockhouses the top storey

was turned diagonally on the lower, thus reducing the amount of

machicoulis fire which could be brought to bear, but allowing the total

fire-power of the blockhouse to be used more efficiently.

The Fort Edward blockhouse was built with an overhang of 17 inches on

all four sides. Machicoulis fire could be directed by removing boards 11

inches wide which ran around the whole perimeter of the upper

storey.

Fort St. Joseph blockhouse had an overhang of 18 inches around the

perimeter of the building allowing machicoulis fire to be directed

downward through loopholes cut through the floor of this overhang. Plugs

were fitted into the loopholes when they were not in use.

The St. Andrews blockhouse had an overhang of two feet on all four

sides. Loopholes were cut through this projection.

The octagonal blockhouse at Coteau-du-Lac had an overhang of 18

inches on all eight sides. There is no information available on

machicolation.

The Narrows blockhouse was built with a two-foot overhang around the

perimeter of the second storey. Machicoulis fire could be directed

through four portholes cut in the overhang located in the middle of

each wall directly below the loopholes. The gunports consisted of a

removable pine board 16 inches by 3 feet 4 inches by 2.5 inches

thick.

The Fort Wellington blockhouse is the one instance of blockhouse

construction in Canada in which the overhang was actually a separate

gallery around the perimeter of the third storey. It was a framed wooden

gallery three feet wide supported by huge stone corbels projecting from

the top of the second storey. Eight doors led out to this gallery from

the third-floor barrack area. Machicoulis fire could be directed

through loopholes located between each set of corbels. Removable boards

covered these loopholes when not in use.

The top floor of the Madawaska blockhouse was set diagonally on the

lower. Machicoulis fire could be cut through the four projecting angles,

where loopholes were cut along the base of the triangle formed.

Loopholes

Loopholes were cut through the walls of all blockhouses. The garrison

could fire at assailants in the open area around the blockhouse without

exposing themselves. Loopholes were splayed on the outside and toward

the bottom to allow a defender a wide angle of fire.

The Fort Edward blockhouse had 23 single-rifle loopholes in the lower

storey and 24 in the upper. The holes were 4.5 feet above floor level.

Each loophole was cut and angled in such a way that lines drawn through

the centres of all of them would meet in the middle of the blockhouse.

This is an interesting feature and one which gave the blockhouse an

effective 360-degree field of fire.

On the evidence of the available plans, there were no loopholes in

the lower storey of the Fort St. Joseph blockhouse. The reconstructed

blockhouse at Fort George, built on the same plan, does have loopholes

in this storey. The second storey of the Fort St. Joseph blockhouse had

loopholes which were long horizontal slits cut around the whole

perimeter of the fort, centred between the portholes. A board, hinged

above, covered the openings when they were not in use.

There is no information available on loopholes for the St. Andrews

blockhouse.

There is some confusion from plans and later pictorial evidence

concerning the octagonal blockhouse at Coteau-du-Lac. It appears that in

the first storey there were horizontal loopholes in each face on either

side of the central windows. The second storey had long horizontal

loopholes above the portholes in each bay. These would also have let out

smoke when the cannon were fired.

There were no loopholes in the lower storey of The Narrows blockhouse

since it was used for storing munitions and provisions; however, there

were small ventilation ports. The second floor had one horizontal

loophole 4 feet long and 4 inches high in each of the four sides. They

may have had wooden plugs when not in use.

Single-rifle vertical loopholes were cut in the south and southwest

walls of the ground floor of the Fort Wellington blockhouse. The

magazine, armoury and storeroom on this first floor were ventilated. In

the second storey, single-rifle vertical loopholes were cut through the

stone, each splayed outward and

downward. Like the blockhouse at Fort Edward, all were angled in such

a way that lines drawn through their centres would meet in the middle of

the building. In the wooden gallery which formed the overhang on the

blockhouse, the loopholes were six-inch square holes, 14 of them on each

side, cut through the thin gallery walls.

The Madawaska blockhouse had eight horizontal loopholes, each eight

feet long, separated by the four portholes. The same arrangement existed

in each storey. The openings were filled with two-inch pine glazed

sashes. Pine stoppers were hinged under the loopholes to reduce the

opening when necessary.

Portholes and Ordnance

Portholes were cut in all blockhouses. They served the double

function of gunports for ordnance to fire through and ventilation ports.

The openings were splayed to allow guns to pivot in order to increase

the field of fire. Portholes were ordinarily cut into the upper storey,

since that floor projected above the palisades and any ordnance mounted

would be most effective there. Large openings in the lower storey were

usually cut higher in the walls and were intended as windows.

The Fort Edward blockhouse had four portholes in the upper storey,

one in the centre of each side. The openings measured 1.0 feet 5.5

inches high and 1.0 feet 7 inches long. The bottom of each porthole was

1.0 feet 6.75 inches above the floor. The original ordnance consisted of

four-pounders without carriages. Cornwallis was supplied with 40 of

these guns for the blockhouses he contemplated. They probably rested on

swivel mountings.

There were four large openings in the lower storey of the Fort St.

Joseph blockhouse — undoubtedly windows. On the second storey there

were six porthole-windows in each of the long sides and one in each of

the short sides (located near the corner to provide light for the

stairwells). Most likely these openings were simply windows for light

and fresh air, since the upper storey was used as a barracks. The

openings were 3 feet 9 inches above the floor and had ledges on the

outside. Since there were guns mounted on platforms in the four bastions

of the fort, it seems doubtful that anyone ever intended to mount

ordnance in the blockhouse.

The St. Andrews blockhouse had two windows with side-hinged

shutters, located in the side of the lower storey, facing the water.

There were four portholes, one in the centre of each side, in the upper

storey. The blockhouse mounted one four-pounder iron carronade on a

standing wooden carriage.

The first floor of the octagonal blockhouse at Coteau-du-Lac had

openings two feet square in the centre of each face. They were three

feet above the floor. Since this was a barracks room, these openings,

with shutters hinged outside, were undoubtedly intended as windows. In

the second storey was a rectangular porthole measuring 1.5 feet high by

4.5 feet long in each of the eight faces. These portholes were placed

close to the floor. Since the blockhouse was apparently fitted up to

mount a 24-pounder on a traversing platform on this floor, these

openings were intended as gunports. The long slit above each porthole

could serve as a loophole, and would also allow the smoke from the large

gun to escape.

There were two portholes in the east, west and south walls and one in

the north wall of The Narrows blockhouse. The north wall porthole

retains the original dimensions — 33.5 inches long 26.5 inches

high. The other portholes were later enlarged for windows. No

information is available indicating what, if any, ordnance was

mounted.

The four large openings on the second floor of the Fort Wellington

blockhouse are quite high in the wall and suggest that there was no

intention of mounting ordnance here. There are also windows in the

gallery of the third storey. The 1838 specifications for the blockhouse

instructed the contractor to make the windows in the French or English

style, with two-inch-thick frames which were to be glazed.

There were four portholes, 2 feet 8 inches square, in the centre of

each side of the top storey of the Madawaska blockhouse. There is no

available information about the nature of the ordnance mounted. A plan

of the blockhouse indicates curbs and blockings immediately behind each

gunport, suggesting that a traversing gun was intended.

Roofs

All the blockhouses had pitched roofs, necessary (for obvious

reasons) in the Canadian climate. The nature of these roofs was

naturally determined by the shape of the underlying blockhouse. Square

blockhouses — such as those at Fort Edward, St. Andrews, Fort

Wellington, The Narrows and Madawaska — had pyramidal roofs. The

king-post type of support was the rule in these cases, the king-post

often reaching from the peak of the roof through two stories to the

foundation. The long rectangular blockhouse at Fort St. Joseph had a

hipped roof with queen-post truss support. The octagonal blockhouse at

Coteau-du-Lac had an octagonal hipped roof, with rafters spanning from

each of the eight corners and the middle of each face, all bearing on

the central chimney.

The roofs were usually covered with cedar shingles, although the

blockhouses at Fort St. Joseph, Coteau-du-Lac and Madawaska had roofs

covered with sheet metal. Fort Wellington had a tin-covered roof.

An attempt was made at Fort Wellington to make the roof

splinter-proof by filling the space between the tie beams and the roof

with a solid layer of nine-inch-thick cedar poles.

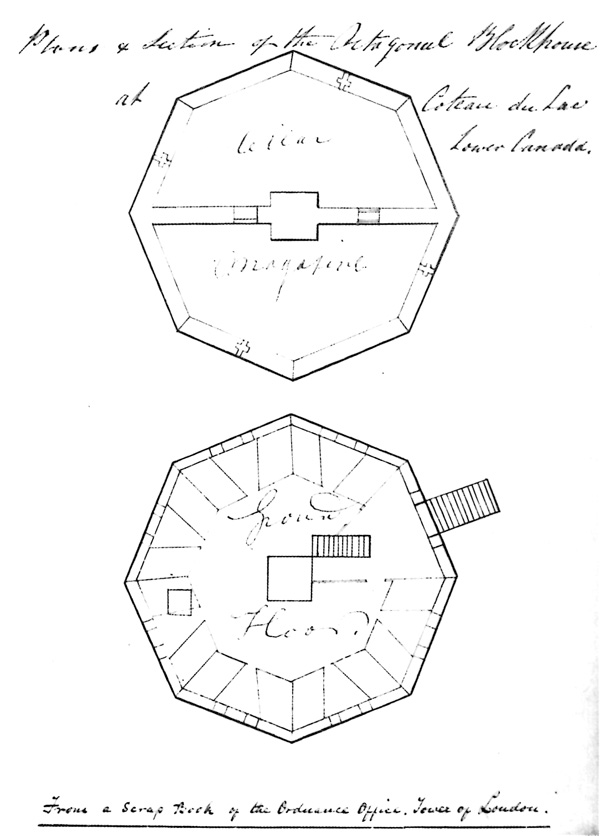

5 Plan of octagonal blockhouse, Coteau-du-Lac, 1823.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

6 Plan and section of octagonal blockhouse, Coteau-du-Lac, 1823.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

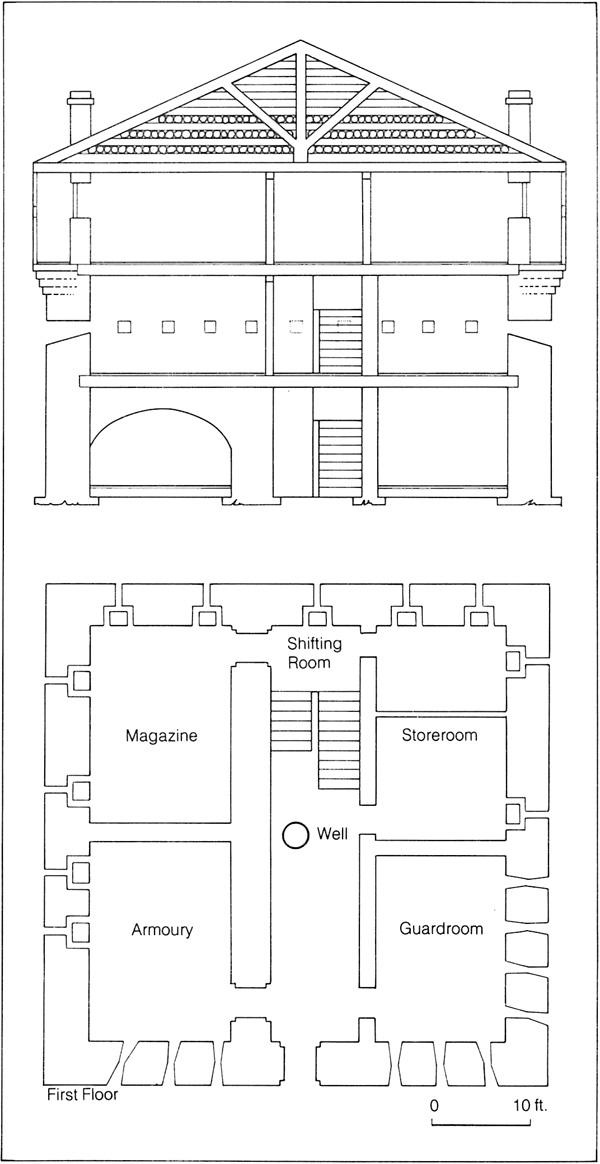

7 Fort Wellington, 1839 blockhouse.

(Drawing by D. Ford from an original in the Public Archives of Canada.)

|

Flooring

The floors of the blockhouses were invariably laid with

two-inch-thick softwood planking.

Heating

In the early period, blockhouses were heated by simple hearths or

fireplaces. As stoves became more readily available in the late 18th

century, these marvelous inventions were introduced. Most blockhouses

had central brick chimneys and could be adequately heated with one or

two stoves, although the larger ones (at Fort St. Joseph and Fort

Wellington) needed more elaborate heating systems. At Fort St. Joseph,

the blockhouse had two interior chimneys, each with two fireplaces on

each floor, making a total of eight fireplaces in the two storeys. The

blockhouse at Fort Wellington had two brick chimneys with a number of

stoves feeding into them on all three floors.

Room Use and Interior Organization

Ideally, the blockhouse served best when it was designed as a

self-sufficient defensible post — the magazine, armoury, store

house and barracks all combined in a single building. Money, time and

labour frequently made it necessary for blockhouses to serve all of

these functions even when they were not designed to do so. They were so

easy and cheap to construct, one of the more adaptable types of

fortification, and had few limitations. In general the blockhouse was

considered an extremely practical defense structure.

The Fort Edward blockhouse was the principal work inside Fort Edward.

It was probably used only occasionally as barracks because the fort

contained barracks sufficient for 200 men. Ordnance was mounted on the

second storey, which was used mainly as a watchtower. The lower storey

probably contained small arms and was used as a guardhouse since it was

situated near the main gate.

The Fort St. Joseph blockhouse was constructed as a

blockhouse-barrack. The lower storey was subdivided by wooden partitions

into four rooms: an ordnance storeroom; a room for provisions and

commissary stores; a room for the Indian Department stores, and a

regimental storeroom. The upper storey was divided into two large

barracks for soldiers and three smaller ones for officers.

The St. Andrews blockhouse was constructed by the townspeople of St.

Andrews to discourage American privateers. It was used as a small-arms

depot and also as a barracks for the artillerymen. Local militia on

active duty also used it. The second storey mounted a four-pound

carronade.

The basement of the octagonal blockhouse at Coteau-du-Lac was divided

into two sections by a stone wall; one room served as a powder magazine,

the other as a cellar for provisions. The first floor was fitted up as a

barracks with three-tiered bunks along the outer walls. The top floor

was intended to mount a 24-pounder on a traversing platform, but it is

doubtful if the gun was ever actually installed. For a time in 1815, the

top floor was used as a garrison hospital where hammocks were hung for

the patients.

The first floor of The Narrows blockhouse was an unpartitioned

munitions and provisions store. The second storey barrack would have

contained about 20 men, but was usually the residence of the lockmaster

and labourers.

The Fort Wellington blockhouse was the largest and most elaborate in

Canada. The first floor of the three-storey stone building was divided

by thick walls into four rooms and a central corridor. The magazine,

located in the northwest corner, measured 20 feet by 14 feet and was

vaulted. The armoury, in the southwest corner, was identical to the

magazine. The other two rooms in the first floor were storerooms, each

of which measured 22 feet by 14 feet 9 inches by 10 feet high. The

second floor was divided into two rooms and, apparently, used as barracks.

The third storey was also used as barracks with a small room

later partitioned off as a hospital. The gallery around the third floor

was planned to be used only for defence.

The first storey of the three-storey Madawaska blockhouse was of

stone. A partition wall two feet thick divided the area into two rooms.

One room served as a commissariat store with provisions for 100 men; the

other as a magazine and artillery store. The second storey of the

blockhouse was used as barracks. Eight wooden berths were headed against

four posts supporting the upper floor, and 16 more bunks were situated

against the walls. Hammocks could also be hung to accommodate additional

men. The third floor had curbs and blocking behind each porthole to

mount a traversing gun.

|