|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 16

The Cochrane Ranch

by William Naftel

The British American Ranche Company

Regrouping

Cochrane had reserves and an alternative plan and as soon as it be

came apparent that disaster had struck for the second winter in

succession, he began to deploy the resources he had been husbanding.

On 21 March 1883 Cochrane was assigned the leases of the Eastern

Townships Ranche Company and the Rocky Mountain Cattle Company held by

his political confrères, Brooks and Colby.1 In addition,

lease No. 26 held by Gagne, Pratt and Company and totalling 64,000 acres

was assigned to James Cochrane. These three assignments received

cabinet approval on 17 April and provided the Cochrane ranch with

170,500 acres of grazing land running southwest from Fort MacLeod

between the Peigan and Blood Indian reserves, and between the Belly and

Waterton rivers to a line of latitude just south of the present town of

Cardston and close to the international boundary. This actually did not

effect the possession of the company's lease of 100,000 acres or so of

grazing land along the Bow River and it is a commentary on the

senator's determination that although he claimed to have personally lost

over $100,000 on his Canadian ranching operations,2 there

seems to have been no question of abandoning the leases. With $15 to $20

thousand tied up in fencing and buildings alone, he had no intention of

writing it off.3

All that was therefore required was an about-face on the subject of

sheep ranching to which he had been so firmly opposed two years before

and this switch was accomplished without much trouble. As early as March

it had become evident to Cochrane that the Bow River leases were "better

adopted for a hardier animal like the sheep," and examples in Montana

could be quoted to show that if the technique known as "close herding"

were adopted, flocks of sheep might graze in cattle lands without the

anticipated damage occurring.4 Again the forces were

marshalled and Colby, who had previously protested strongly against the

grazing of sheep, was persuaded to state that there was ample room in

the Northwest for both cattle and sheep ranchers,5

This conversion prompted a few cynical remarks from David Lewis

Macpherson the new minister of the Interior, and Macdonald.6

The prime minister, moreover, was getting a little edgy on the subject

of ranching companies. Some

8 or 9 companies got Ranches on giving the assurance that they

were both able and willing to stock them. It turns out that they all

lied and merely got their leases for the purpose of selling them....

These speculators [he was not referring to Cochrane] now club

together to make one large Company with a range [?] the size of a

province to speculate upon, and propose to hawk this around in

England.7

Cochrane, however, was immune to difficulties. They could be swept

away in no time. He wanted to raise sheep, he wanted to do it with no

restrictions on numbers, and if Sir Joseph Pope, the prime minister's

secretary, would kindly arrange a meeting with Macdonald, all could be

arranged in a very few minutes.8 Though it took nearly four

months of continual nagging from the end of March until the beginning of

July, the Department of the Interior finally gave in and on 11 July the

company was informed that they might graze sheep on the Bow River leases

on condition that they place five head of sheep for every ten

acres.9

There seems, however, to have been a quid pro quo involved, in

that this concession was seized upon as justification for finally

rejecting Cochrane's claim that the company should be allowed to

purchase five per cent of its leasehold, which claim he had been

pressing vigorously up to this point. However much of an non

sequitur the comment may seem, Macpherson observed that, in view of

Cochrane's desire to withdraw his cattle and replace them with sheep,

the company had therefore lost all claim to purchase five per cent of

the leasehold.10 The senator may have accepted this as part

of a bargain; certainly the flow of letters on the subject from himself

or his agents stopped once he received permission to graze sheep.

This, however, did not solve the entire sheep-versus-cattle question

and the matter was the subject of much debate in the grazing country

where a number of persons were expressing keen interest in sheep

raising. Petitions pro and con were forwarded to Ottawa: the South

Western Stock Association of Fort MacLeod urged that sheep not be

permitted in its territory: 124 residents of the Sheep Creek and High

River areas asked that sheep not be banned from their

district.11 During a visit to the Northwest in the summer of

1884 the deputy minister of the Interior, Burgess, discussed the subject

with various interested parties and the result was the formulation of a

new policy. Henceforth sheep were free to graze without permit in the

territory north of the Highwood and Bow rivers, while south of that line

the grass was reserved for cattle alone.12

Unlike the American situation, the bitterness between sheepmen and

cattlemen never developed to any great extent although it was certainly

there and from available evidence it would seem that the boundary

arrived at was mutually satisfactory The decision is perhaps most

interesting for the purposes of this paper insofar as it reflects the

decline in favour of the Bow River district in the eyes of cattlemen. In

1881 it had been considered the prime cattle grazing country by experts

and investors. After two disastrous winters for the Cochrane stock, its

abandonment to sheep raised scarcely a murmur from the big ranchers

whose centre was now Fort MacLeod.

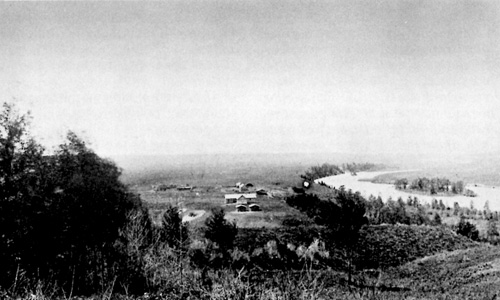

21 Living quarters of the British American ranch, circa 1886, Ernest

B. Cochrane on the couch.

(Glenbow Alberta Institute.)

|

Establishment

As soon as matters were well in hand on the new range at Fort

MacLeod, attention was turned once more to the Bow River leases and in

February 1884 a new company, the British American Ranche Company, was

incorporated to handle them. The new company did not arrive in a very

happy atmosphere for the collapse of cattle ranching at Big Hill after

two costly years had led to strains in shareholder relationships and

management in both the East and the West. At Big Hill the capable

Kerfoot had threatened to resign in January 1884, probably over

disagreements with Montreal. In Montreal the annual meeting of the

shareholders of the Cochrane Ranche Company in February 1884 was

characterized by some bitter in-fighting. McEachran at one point accused

White, Browning and Cochrane of holding private meetings on company

business behind his back, while Browning and Cochrane accused McEachran

of doing all he could in his power to ruin the credit of the company and

by his conceit and pomposity hindering his own advancement.13

The meeting was generally an unpleasant one and one of its

accomplishments was a surreptitious move to dismiss White. This came to

nothing when McEachran refused to co-operate.14 In the end it

was left to Cochrane to remark tactfully while he was out West in July

that the directors would be glad if White would relieve them of the

expense of management as soon as he could do so without loss to

himself.15 The implication seems to be that White was a

scapegoat for the company's difficulties. He had already been replaced

as treasurer that spring by A. E. Cross.

On a more constructive level, this particular meeting made

arrangements to dispose of the Cochrane ranch holdings to its new

corporate entity, the British American Ranche Company.16 The

new company may have been formed more from the necessity of preserving

the government from embarrassment than any other reason for under the

terms of its charter the Cochrane Ranche Company could have raised sheep

and horses without the necessity of another incorporation. In strictly

legal terms, the statutory limit of 100,000 acres per lessee was not

encroached upon as the over one-quarter million acres controlled by the

Cochrane Ranche Company around Calgary and around Fort MacLeod was held

in the name of a variety of separate individuals and corporate entities.

Nevertheless, perhaps for political reasons or possibly as a means of

raising new capital, the company was established which had the effect of

whittling the acreage down to a size more in keeping with the spirit of

the law.

On 19 January 1884 Cochrane, Hugh MacKay, William V. Lawrence,

William Cassils, Charles Cassils and William Ewing, all but Cochrane

residents of Montreal, submitted a petition for Letters Patent of

Incorporation for the purposes of "breeding and rearing of horses, mules,

sheep, cattle and swine" in the North-West Territories. The proposed

capital was $200,000 to be divided into 2,000 shares of $100 each of

which 1,030 were subscribed by the petitioners. The largest shareholder

was William Cassils with 420 shares, but 400 of these were held in

trust. The senator held 300 and his son-in-law, Charles Cassils, held

50.17

The required letters patent were granted on 5 February and two weeks

later on 19 February the new company bought the Bow River leases from

the Cochrane Ranche Company for $55,000.18

The way was not all clear yet for the Department of the Interior of

1884 was not the relatively compliant institution of 1881. In March 1885,

following the example of the parent company, the British American Ranche

Company filed assignments for leases totalling 189,000 acres. This

covered the 100,000 acres of the original Cochrane lease, the 55,000

acres of ranch No. 44 originally leased to Baynes and in December 1882

assigned by him to Browning and the 33,000 acres of ranch No. 43 leased

to A. W. Ogilvie and assigned by him to the Cochrane Ranche Company in

June 1884.19 Once these assignments were filed, the

department consulted the Department of Justice on the legality of

registering them. The Justice Department replied that whatever the

original intent of the legislation, nothing specifically forbade the

assignment of leases.20 Accordingly, approval was given on 26

May 1885.

Horses

The British American Ranche Company had been incorporated for nearly

a year before it took possession of the leases. In the interim, between

the time the cattle left and the British American Ranche Company became

an active operation, Kerfoot introduced an aspect which had hitherto

played a minor role — horse ranching.

By June 1883 about 490 horses were on the range south of the

Bow21 and over the next few years these were built into a

good-sized herd: 550 head in May 1885 and 609 by September of that year.

In November 1886 after the purchase of the "Harper Band,"22

one of the finest herds in the West and probably from the Gang ranch in

British Columbia, the horses, now legally part of the British American

Ranche Company, reached their peak in numbers — 1,013. A year later

there were 964 horses and at the time of the sale of the assets and

transfer of part of the lease to the Bow River horse ranch in August

1888 there were 920 horses.23 The number of pure-bred

stallions imported to raise the quality of the stock began with four,

two thoroughbreds and two Clydesdales. This was increased in 1885 by

four half-bred Percherons and then, with the addition of the Harper band

in 1886, to a total of eight thoroughbreds and six half-breds, with an

emphasis on the Clydesdales and Percherons. At the time of the sale

there were nine thoroughbreds and one half-bred.

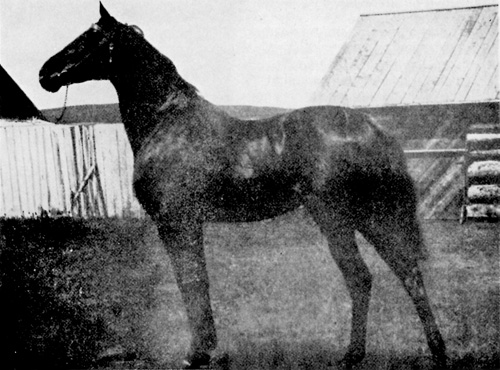

22 Konrad, foaled in 1874 by Rebel Morgan and brought in with

Cochrane's first herds, was the first thoroughbred in Alberta.

(L. V

Kelly, The Range Men: The Story of the Ranchers and Indians of

Alberta (Toronto: Briggs, 1913.)

|

Horse ranching became a major part of the British American Ranche

Company's operations and to handle it the lease was in effect divided in

half. Buildings and corrals were erected on the south bank of the Bow

River where Jumpingpound Creek debouches. This involved the expenditure

of a fair amount of capital so it is evident that a good return was

expected.

The demand it was intended to supply was a mixed one. It is evident

from the proportion of heavy draught animals among the stallions that

much of the market was expected to be homesteaders looking for farm

animals to pull plows and wagons. Cowboys' interest was expected and

great hopes were placed in the need of the North-West Mounted Police for

remounts. However, none of these markets developed to any great extent.

Settlement lagged even after the completion of the CPR and the expected

population explosion simply did not occur for another decade. Cowboys

were a limited market and initially it proved exceedingly difficult to

persuade the Mounted Police to buy their horses locally rather than from

eastern breeders. The effort was hardly worthwhile. The decision to

dispose of the Bow River properties was taken in late 1887 and the

buildings, implements, lease and lands of the horse-ranching operation

south of the Bow River were sold to the Bow River Horse Ranche

Company.24

Sheep

In stocking the new sheep ranch, the same procedure was followed as

had been used for starting a cattle herd: foundation stock was imported

from the western United States, mostly Montana and Wyoming, and purebred

rams were brought in to gradually raise the quality through careful

breeding. The American stock was mostly Merino and Rambouillet in

background, crossed with Shropshires or Oxfordshires.25 In

April 1884, along with the announcement of the purchase of the Bow River

operations, the British American Ranche Company also stated its

intention of importing some 6,000 sheep.26 The actual number

imported, however, may have been rather more, somewhere between 7,000

and 8,000 depending on which of the available figures are

used.27 The purebred stock consisted of some 2,000

Shropshire rams which arrived on the ranch in

mid-October.28

The usual jinx seemed to be operating when the arrival of the sheep

was signalled by a heavy snowstorm, but then the situation began to

improve. For one thing, the sheep had been driven slowly and were in

good shape — "fat as butter" was one comment.29 For

another, despite the early snowstorm, the winter of 1884-85 was the

kind that the publicists wrote about — mild and open — so the

sheep were able to forage on their own, requiring no hay until February.

By mid-February the snow had vanished, the streams and springs were

reopening, and the sheep had come through splendidly. Thus far the

operation gave every prospect of bearing out the hopes of its promoters

and of the deputy minister of the Interior, Burgess, who felt that is

was bound to become a valuable industry within a very short

time.30

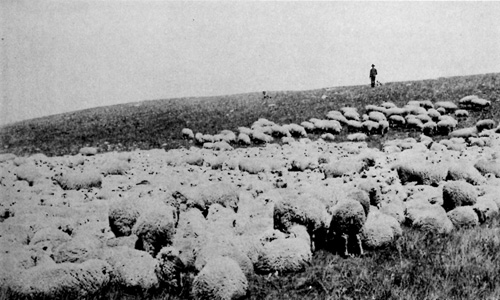

23 A band of sheep on the British American ranch, circa 1885-88.

(Glenbow Alberta Institute.)

|

With all this cheerful outlook after the successful wintering of the

herd had become a matter for public comment, disaster struck when a

prairie fire caught some of the sheep and 400 died in the

flames.31 It was a bitter blow and Kerfoot stated publicly

that the fire had been deliberately set in order to damage the stock.

Nothing more was heard of this charge, but it was an indication that the

emotions which sparked bitter range wars in the United States were not

entirely absent from the Canadian experience.

Nor was this the last misfortune. L. V. Kelly records that a corral

into which had been herded a large flock of sheep was drifted in during

a late snowstorm, allowing the sheep to wander off over the fence.

Driven by the storm, they headed across country until they come to a

deep slough three miles away and there 300 drowned. Another heavy loss

is said to have occurred at lambing when "hundreds and hundreds" of

ewes died giving birth.32

Possibly because of these misfortunes, Browning qualified the

company's commitment to stock the range with the statement that the

sheep had been placed on the range, "with a view to testing the fitness

of that . . . section for sheep grazing."33 Late spring saw

the company with about 8,000 sheep which may or may not represent an

increase as two sets of figures are available for the number of sheep

actually imported. Even after the main lambing season was well over, the

size of the flock had increased to only 8,200. The sheep ranching

operations of the British American Ranche Company never developed beyond

this stage. In late 1866 there were 7,525 sheep on the ranch, the

following year, 7,439, and in 1888 8,570.34 Proposals to

erect a woollen mill near Calgary did not come to fruition until long

after they were first made in 188335 and the wool clip, which

in the first season amounted to 50,000 pounds, was sent to Montreal for

disposal.36

Though the British American operations, both sheep and horse, never

suffered the major setbacks of its predecessor on the site, there was

never any of that run of good fortune so necessary in the initial years

of a new operation. Management troubles persisted and in 1887 Kerfoot

resigned. It appears to have been the same old story of conflicts

between an eastern-based management and a western operation and many

disagreements arose when directors' decisions had unhappy results for

which Kerfoot received the blame.

Kerfoot's resignation was a stormy one and he eventually sued the

company successfully for the remainder of the salary due on his

five-year contract.37 Nevertheless, he remained bitter over

what he considered his bad treatment by the management. He went into

ranching in partnership with his father-in-law, W. Bell Irving, just

west of the British American ranch lease, and prospered. He died in 1910

in the parade of the Spring Stock Show in Calgary when his horse fell

and crushed him.38 His replacement as manager was Ernest

Cochrane, the senator's youngest son, who might be expected to be more

amenable than his predecessors to direction from Montreal.

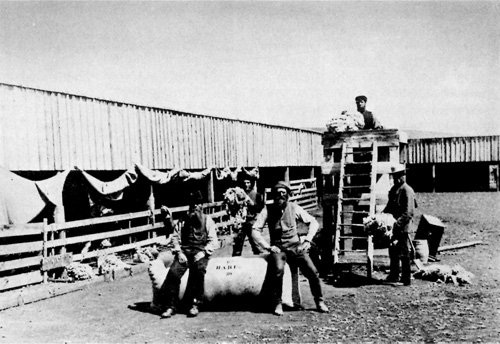

24 Baling wool on the British American ranch, circa 1885-88.

(Glenbow Alberta Institute.)

|

There were other problems. L. V Kelly mentions such things as

disease, bad water, unfortunate accidents, thieves and

storms.39 One major difficulty was presented by wolves which,

deprived of the buffalo, found a welcome substitute in the herds of

cattle and sheep which replaced them. The company kept a pack of

wolfhounds which proved useful in controlling the wolves, but losses

remained high.40

Possibly of more moment than the various handicaps imposed by nature

were those imposed by man, of which two, rental and markets, will be

noted briefly and the third, instability of the leases, discussed in

some detail. In 1885 the rental of the leased lands had been doubled

from one cent to two cents per acre. When dealing in tens of thousands

of acres, such a rise was not insignificant although even by the

standards of the day the rental still seems a bargain.41

Though it roused the protests of George Stephen, president of the CPR,

who saw one of the few prospects of long-haul freight diminishing before

his railway had scarcely got up steam, the Department of the Interior

stood firm.

As far as markets were concerned, the company had the misfortune to

enter the field just as Australia was rapidly developing into the

leading wool and mutton producer in the world. Between 1881 and 1891 the

number of sheep in Australia increased from 78 million to 125 million

and concurrently the price of wool dropped to a level that made life

difficult for Canadian producers.42 William Pearce summed up

the situation in Alberta as it stood in 1889.

The low price of wool has retarded this industry, which when

prosecuted on a large scale does not appear to have been a highly paying

enterprise; at the same time, in every case where a settler has not had

more sheep than he could personally look after — that is a flock of

from 500 to 2,500 — it has proved most

profitable.43

Assaults on the Leasehold

Probably the most serious and certainly the most interesting of the

problems which led to the winding up of the British American Ranche

Company were those connected with maintaining the leasehold intact, a

problem which remained insurmountable not just for the Cochrane

interests, but also for every rancher in the Northwest. Two forces were

acting to break up the leases: the corporate interests of the CPR and

the Hudson's Bay Company, and the individual interests of the

homesteader-squatter. Of the two, the CPR and the Hudson's Bay Company

were acceptable because they operated from a statutory basis and

acceptance of their land claims was inherent in signing a lease, but the

squatter was dangerous because he acted outside the law, considering it

of no account in the face of his land hunger.

The CPR had been granted 25 million acres of land in the Northwest

which its agents were to choose from the odd-numbered sections and the

Hudson's Bay Company received, in addition to a cash settlement, 1/20 of

the land in the fertile belt. The Cochrane leases stood athwart the main

railway line as it was announced in September 1882 and the CPR and the

Hudson's Bay Company were well aware of this convenient location. Hence

the lands were a prime target and considerable areas were turned over to

the two companies. Up to 1 November 1886 this had totalled 37,160 acres

and over the next two years the total mounted rapidly until by 1 May

1888, a total of 116,394 acres were withdrawn from the operation of the

lease.44 This was not the set-back it might seem for the

companies had no intention of disposing of them immediately and were

quite content to continue leasing arrangements. Nevertheless over the

ranching company's objections,45 they had now to pay rent to

at least two different masters, the government and the companies,

one of whom might dispose of its holdings at any time with a minimum

of notice. Ownership of half of its leasehold by a private corporation,

while it does not seem to have hampered the ranching operations in any

way, added one more element of insecurity to those which already

existed.

Of a much more serious nature were the actions of the agricultural

squatters who plagued every large ranching outfit in the Northwest.

Squatters were living proof of the adage, "The grass is always greener

on the other side of the fence." It is difficult to support their

actions especially in the early years before the turn of the century.

With countless millions of acres of some of the finest agricultural

land in the world free for the asking between Winnipeg and the Rockies

on fulfilment of minimal conditions, some individuals headed straight

across the empty prairies to the reserved grazing leases. There they

settled on some spring or stream, declaring that no other spot would do

and that anyone who suggested they move elsewhere was a tyrant and a

despot.

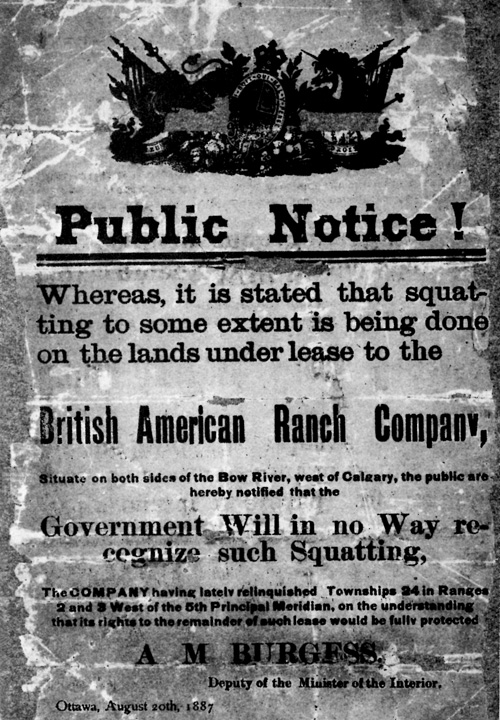

25 Notice to squatters.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

In resolving this problem, Macdonald's government was of very little

help for, though the lease-holders clearly had the law on their side,

the towns, which resented any restriction on settlement and hence

business, and the settlers represented heavy political pressure. The

government learned early that any strong action was interpreted as

aiding vested interests in suppressing the "little man." Worse still,

in its immigration propaganda it had consistently given the impression

that every single acre in the Northwest was available for

homesteading.

The problem was compounded by the fact that while many of the

squatters seem to have been genuinely interested in settlement, others

were well aware of their own nuisance value and in many cases they made

it clear that they would be willing to move on if they were compensated

for their "improvements."

The first open challenge to the position of the lessees came early.

At a settlers' meeting held in Ellis's billiard hall in Calgary on 10

October 1882, called to discuss the system of reserving land from

settlement for ranches, townsite reserves or Indian reserves, a resolution

was carried unanimously which stated, among other things.

That whereas the Dominion Government has seen fit to grant leases

for cattle ranges already, covering nearly all the good agricultural

land in the best portion of the proposed Province of Alberta. . . . That

it is also the opinion of this meeting that the provision in the leases

empowering and compelling the lessees of cattle ranges to prevent the

location of settlers upon the land so leased, is objectionable and

contrary to the best interests of the country.46

The most interesting feature of this resolution was the fact that its

mover, E. A. Baynes, was Cochrane's son-in-law. While he and Cochrane

never got along well,47 it seems unlikely, at least at this

early stage when his connection with the Cochrane ranch was close, that

Baynes would have moved such a resolution without the senator being in

some way aware of what he was doing. Certainly he would be representing

the views of the Cochrane ranch when he objected to an amendment to his

resolution (which nevertheless received an overwhelming majority) that

the ranchers be given two years notice.48

There is a possible explanation for the anomalous position taken by

Baynes in moving his resolution. Slightly rephrased, it would in fact

approximate the position of the Cochrane ranch and the other working

ranches as well. In an 1884 interview Browning stated the company's

position at that time.

While the ranchmen claim that they have the entire rent of the

land leased to them, they have no desire to exclude bona fide

settlers from such portions of their leases which may not be

necessary for grazing purposes. The trouble heretofore has been in

squatters, not settlers, going upon choice hay lands, valuable river

fronts, and lands with springs which are absolutely necessary for cattle

during winter, with no intention of settling, but with the object of

being bought off or selling their pretended rights to innocent

settlers. What the ranchemen think they are entitled to is that parties

desiring to settle upon their leases should ask and receive permission

to do so before attempting to take possession, and where there is not

good reason for refusing their request, they may rely upon being allowed

to occupy the land.49

As expressed, this viewpoint was reasonable enough to appeal to the

new deputy minister of the Interior, A. N. Burgess, on his first trip to

the Northwest during the summer of 1884. While in the grazing district

he discussed the question with a number of the lessees and found all but

one or two in favour of the location of settlers on the leases. He

concluded that despite efforts to create an impression to that effect.

no necessary or natural conflict existed between the agricultural

settlers and the grazing leaseholder. He illustrated his contention with

reference to the problems of the Cochrane herds, suggesting that had

there been scattered throughout the lease from 50 to 100 settlers

engaged in mixed farming from whom hay could have been purchased, a large

proportion of the cattle lost might have been saved. Aside from that,

the presence of settlers would mean a ready supply of extra help at

round-up time. On the other hand, he noted firmly, those who trespassed

on the leases with the idea of going into competition with the lessee,

probably using his bulls and stealing a few calves now and then or with

the intent of extorting some consideration for leaving, deserved no

sympathy.50

So eminently reasonable was this view that Macdonald accepted it. It

was absurd, he said, to suppose a great industry which would supply the

remainder of the Northwest with their stock cattle could be allowed to

be destroyed at the mere caprice of a few squatters. The government

would not, he continued, allow its policy in this matter to be impeded

by every squatter who chose to come in on these lands when there was

plenty of land in other parts of the country.51

Unhappily for the ranchers, this was about as far as government

action went and despite the fine words they were left pretty much to

deal with the situation as it arose. In these early years the ranchers

almost invariably eschewed violence and resorted to legal proceedings or

else made the required payment for "improvements." Hence in May 1883

White bargained with a couple of squatters named Heath and Jones who had

settled on the southern range. White offered them $800 to get off, but

they held out and received $1,000 "for their improvements."52

This attitude, in sharp contrast to the direct action with gun or rope

so common in the United States, is at least partly explained by the

prevailing philosophy of law and order. At one time rustlers were

flourishing in the Pincher Creek area and a group of ranchers met to

discuss the menace. The identity of the culprits was suspected and many

felt that action should be taken; lynching was one remedy suggested and

feeling was running high. At this point one of the leading men, E. W.

Godsal, said, "But, gentlemen, the British just don't settle matters in

this way." To this there could be no argument: the meeting ended and

they all went home.53

As the railway grew closer, however, would-be settlers became more

frequent and tempers grew shorter. Whether for blackmail or for farming

purposes, the settlers picked the finest locations on springs and river

flats. By 1887 25 miles of continuous fence between Fort Kipp and Slide

Out on the Belly River shut out the range cattle from the water and the

shelter of the valley.54

The attitude of sweet reasonableness which had prevailed did not

interest those eager for land. No matter how polite the procedure, an

eviction was an eviction and all of those whose title to their land was

vague watched with increasing uneasiness as ranchers exerted themselves

to maintain their leases inviolate. The resentment of squatters and

settlers at the refusal of the government or the ranchers to concede

immediately what was considered to be the "right" of homestead entry

boiled to the surface in a meeting held at the farm of John Glenn on 5

April 1885 at which was formed the Alberta Settlers Rights Association.

In the language of outrage their spokesman, Samuel Livingstone,

telegraphed the resolve of the meeting to Sir John A. Macdonald. All

the townships about Calgary ought to be immediately thrown open for

homestead entry and settlement and settlers therein who had complied

with the normal homestead requirements should be granted their patents

"immediately." Further, settlers ought to be allowed to import cattle

on the same terms as the lessees; that is, free. To reinforce their

demands and indicating the depth of feeling over the issue, the meeting

concluded by pressing for immediate action "to prevent repetition of the

trouble which now unhappily exists in these Territories" and resolved

further "that the halfbreeds in these Territories are entitled to and

should receive the same privileges as regards lands as have already been

conceded to their brethren in Manitoba."55 Coming little more

than a week after the confrontation at Duck Lake which heralded the

Northwest Rebellion, such language was extreme indeed, though it was

more temperate than John Glenn's threat uttered at the meeting to hold

his land "with a shot gun."56

In a sense, however, the result was a degree of success for the

government made immediate, if discreet, inquiries through local

contacts. The information received tended to discount the Alberta

Settlers Rights Association as a front for lawyers and

merchants,57 but actions of the government thenceforth with

regard to the leases indicate that they had recognized the political

strength if not the legal validity of the settlers' compliants.

The years between 1885 and 1892 were bad ones for the ranchers. The

two men who occupied the post of minister of the Interior during that

period, Thomas White and Edgar Dewdney, were inclined to favour the

settler. One of White's first moves was to revise the terms under which

grazing leases were held. This was done, interestingly enough, simply by

ministerial order despite, or perhaps because of, its very considerable

significance.58 This procedure avoided the requirements to

publicly proclaim an order in council or act of parliament. Under its

provisions, on leases granted in future, homesteaders were entitled to

take up land on the same terms as on Dominion lands and to settle

without first receiving permission of the lessees. Furthermore, no more

grazing leases would be approved for as long as 21 years and old leases

would be cancelled whenever opportunity offered. The old leases,

however, were not abrogated unilaterally but remained in force and

settlers were still required to seek permission if they wished to

settle. This requirement, however, seems to have become increasingly a

dead issue, so much so that Dewdney (then lieutenant governor of the

North-West Territories) was said to have told those settlers who asked

his advice to go ahead and settle on the leases and the ranchers would

not attempt to turn them off.59

The British American Ranche Company found itself in an unenviable

position with the eastern borders of its lease within a few miles of

the mushrooming town of Calgary. The position was made more awkward on

account of "many citizens of Calgary being agitators against

leaseholders."60 Accordingly under some pressure from the

Department of the Interior which in turn was under much pressure from

settlers, the British American ranch agreed to give up Township 24,

Range 2, the area of the lease closest to Calgary.61 Delay

in implementing this agreement, reached in late summer 1886, aroused

fierce resentment among settlers "who pinned their faith to the promises

of a cabinet minister who is supposed to be an honorable

gentleman."62 The minister was asked rhetorically, "how it

comes that one company hold [sic] 80,000 acres of leased land,

lying waste, with the conditions unfilled, when good settlers are being

refused 160 acres each" and it was suggested that Albertans would like

to know "which the government desire to have in Alberta, bullocks and

wethers, or settlers."63

The minister, however, was hardly neglecting the interests of the

settlers for at the end of March 1887 he was pressing Cochrane to

relinquish an additional township.64 Cochrane agreed, extracting

in return a promise that the department would do its best to protect his

rights to the balance of the lease. The minister himself wrote:

The promptness with which your Company gave up the two townships

in order to remove difficulties with settlers, makes me feel very

anxious to protect you, so far as the Government can, in your remaining

territory, and you may depend, therefore, upon our doing whatever is

properly within our power.65

He was to have plenty of opportunity to indicate the extent of his

power for Browning had just submitted a bitter complaint about the

activities and attitudes of the squatters. According to Ernest Cochrane,

who was now the manager,

Morrison was out among some of the settlers

the other day, pretending to be looking for land — he asked

one man if the B.A.R.C. Coy would not turn him off if he settled on

their lease and the fellow's answer was "Oh, show them a box of matches

and they will leave you alone" and then proceeded to tell how he was on

one of the Townships lately thrown open, but if he had not got his entry

before long he would have done some burning.66

It is unfortunate that at this juncture the company would seem to

have overstated their case, or rather had not undertaken to properly

document it. That summer Burgess visited the Northwest and made a point

of thoroughly investigating the complaints in Browning's letter. In June

and in July he paid separate visits to the range in company with Ernest

Cochrane and the superintendent of mines, William Pearce. Unhappily

for the company's credibility, all that was located, aside from some

empty houses which were possibly not even on the range, was one

squatter. On speaking to the man, nobody was more surprised than Ernest

Cochrane to learn that the man was on an odd-numbered section that he

had bought from the CPR after the ranch company had declined to buy it.

About all this trip netted the ranch company was the frosty observation

from Burgess that "The officers of the Ranche Company should inform

themselves, much more definitely in regard to the position of the

trespassers they complain of before any action on the part of the

Department would be justified."67

Much more damaging from the long-range point of view was Burgess's

advice to the minister that it would be difficult to defend warning

trespassers to move from even-numbered sections in the more remote and

less used portions of the leasehold in the face of the fact that the

company had refused to purchase an odd-numbered section in part of the

range which was valuable for its hay.68

This was unfortunate for the company and indeed for the future of the

big ranches for, as subsequent events make clear, squatters certainly

were on the land and were to cause a great deal of trouble. It is not

improbable that this incident coloured the department's attitude for

some time to come. The Department of the Interior did, however, go so

far as to approve a warning to would-be squatters that no claims to

land on the British American ranch's lease would be recognized. This

notice was drawn up by William Pearce as the result of a meeting between

Ernest Cochrane and the minister on 20 August 188769 and

widely distributed by the company as well as published in the newspaper.

but to no avail. Though Pearce, the department's man on the spot, became

increasingly sympathetic,70 in the end it made little

difference.

By the fall of 1888 some 15 squatters on the lease had openly taken

possession of choice portions. A petition in their favour was being

circulated in Calgary under the benevolent eye of D. W. Davis,

Conservative MP for Alberta, and it was signed by every leading citizen

and merchant;71 the Calgary press had been producing

indignant editorials championing the little man versus the big

company72 and on 3 August 1888 Dewdney succeeded to the post

of minister of the Interior after seven years as lieutenant governor of

the Northwest. Dewdney made no secret about his desire to people the

Northwest with industrious homesteaders and in his view hundreds of

thousands of acres locked up in grazing leases would accomplish nothing

toward that end. Publicly the department was as committed as ever to

support the legal rights of all parties, but privately the outlook was

not good for the lessees. Although the squatters case was legally shaky,

they were evidently in his favour. Concerning the petition of the

squatters on the British American ranch, Burgess (who invariably

reflected the prejudices of his superiors) advised Dewdney, "It is quite

clear that if we are to touch this case at all in the interests of the

settlers, it must be by way of a compromise."73

26 Bow River horse ranch, west of Calgary, circa 1885-88.

(Glenbow Alberta Institute.)

|

Withdrawal

By this time, however, the British American Ranche Company and the

Cochrane family were well on their way to withdrawing entirely from

the Bow River, a decision which had been made by November 1887 if not

before. At the annual meeting of the shareholders on the eighth of that

month the directors were authorized to sell, transfer or otherwise

dispose of the assets of the company and wind up its

affairs.74 By June 1888 all the horses and the buildings,

implements and lands south of the Bow River had been sold to the Bow

River Horse Ranche Company, an outfit financed and managed by a group of

English capitalists. The area remaining in this part of the lease

amounted to about 23,788 acres and its assignment was approved by the

cabinet in January of the following year (Fig. 29).75

27 William F. Cochrane, "manager of the Cochrane Ranch until it sold

out to the Mormons."

(L. V. Kelly, The Range Men: The Story

of the Ranchers and Indians of Alberta (Toronto: Briggs,

1913].)

|

In June 1888 the senator had still evidently intended to keep his

hand in by some means and he took steps to retain, in the name of the

British American ranch, part of the lease north of the Bow, Township 26,

Ranges 2 and 3, and Township 25, Range 2, the rest to be given up for

settlement. Despite these adjustments in January 1889, the government

was still pressing in favour of settlers and Burgess suggested that the

company be asked to give up that part of their tract lying nearest

Calgary.76 Since they had just given up three townships, this

further request, made when Cochrane was in Ottawa for the opening of

Parliament, may have been the last straw. Whatever the reason, at a

meeting with departmental officials on 11 June, Cochrane agreed to give

up the remainder of the lease "in order that there may be no obstacle,

so far as the company are concerned to settlers obtaining entry for

lands within the leasehold,"77 on condition that the

government sell to the company three-quarters of Section 10, Township

26, Range 4 at the going rate of $2.00 per acre and grant Ernest

Cochrane homestead entry for the remaining quarter-section. This section

was the site of the company's headquarters buildings. Such a settlement

was agreeable to all. On 27 September 1890 the sale of the

quarter-sections to the company was finalized and Ernest Cochrane

obtained his patent for the remainder on 13 April 1892.78

(Ernest Cochrane's patent was cancelled in November 1900 in favour of

the Cochrane Ranche Company and in August 1905 the patent was sold

outright to Peter Collins.)

On 29 August 1888 the Calgary Herald carried an advertisement

for the sale of 7,000 head of sheep and 41,000 acres of

leasehold.79 Most of the sheep, it is said, were bought by

Thomas Ellis, a settler on Jumpingpound Creek who had come with his

family from Lanark County, Ontario, in 1886.80 The leasehold

was, as noted, returned to the government. However, the company remained

in the sheep-ranching business on a reduced scale for a short time as

they still had 4,000 sheep on the range in 1889 although officially

classed as a non-lease holder:81 evidently it was not

possible to dump an entire flock of over 8,000 sheep on the market at

once. The company itself maintained a corporate existence for some time.

In 1896 it still held title to the three quarter-sections around the

ranch headquarters at Cochrane, subject at that point to a writ of

fieri facias (a writ employed against the goods of an

unsuccessful defendant). This writ, dated 26 February 1896, was issued

in the suit of the Cochrane ranch versus the British American ranch, the

amount in question being $1,680.33.82 It had evidently proved

more difficult than had been foreseen to disentangle the operations of

the senator's two companies.

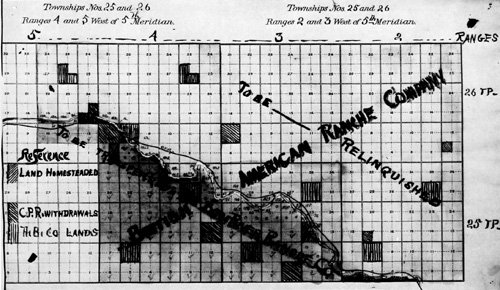

28 Map showing the disposition of the British

American Ranche Company lease, April 1887.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

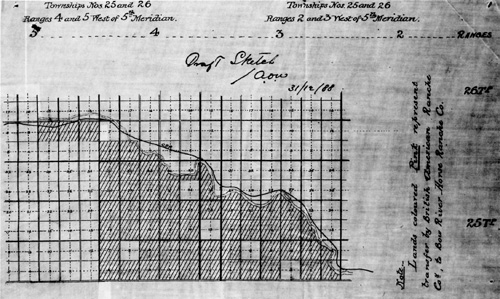

29 Map of Bow River horse ranch, December

1888. Lands coloured pink on the original are indicated by hatching.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

The disappearance of the sheep-ranching operations of the British

American ranch was not an isolated incident comparable to the withdrawal

of the cattle operations to the south. Despite McEachran's observation

in 1887 that the industry was "eminently successful,"83 by

1889 the commissioner of the North West Mounted Police could state that

"The large sheep ranches are disappearing and I think the industry will

resolve itself into keeping small flocks on

homesteads."84

Had the world price for wool remained high, the British American

Ranche Company would have fought to stay in business. As it was, the

nuisance of squatters and wolves combined with a generally unprofitable

world trade situation made it simply not worthwhile to continue in

operation.

|