|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 16

The Cochrane Ranch

by William Naftel

Empire

The First Cattle Drive

By early summer 1881 some stock was already on the range, a number of

thoroughbred stallions and mares brought out by Cochrane and McEachran.

These were quartered at a ranch on the southern edge of what was to be

the lease at the point where it met the Elbow River (probably that

shown on Fig. 13 as "Ranch bought from King") which was under the

supervision of E. A. Baynes the senator's son-in-law; a Mr. Baxter, and

six former Mounted Police.1

Shortly after this the first lot of the imported breeding stock

arrived; six purebred Shorthorns and one Hereford, all bred at

Hillhurst.2 By autumn about 50 purebreds had reached Big

Hill, travelling via rail and steamer to Fort Benton and on foot to

Calgary. They were principally Herefords with some Aberdeen Angus and

Durham Shorthorns, all under two years old and averaging in cost

$140.86. The Angus, it was observed, stood the long journey best,

followed by the Herefords.3

While these represented but a part of the 300 or so purebred stock

planned to be imported, they were only a fraction of the total stock,

which was to be brought in from the United States. The range cattle had

no particular breeding, but they were a step up from the wiry longhorns

common before the arrival of the railway in the central states made long

exhausting drives unnecessary. The process of bringing this basic stock

of range cattle up to an acceptable standard through breeding them to

the purebred bulls accounted for a lengthy delay before the ranch was

expected to make a significant return on the capital investment.

Walker was in charge of buying the cattle, a job he began early in

the summer of 1881. This was no easy task as the good market for beef

which made ranching such an attractive proposition did not

differentiate between beef cattle and breeding stock, hence prices were

high. The Chicago Times noted:

The strong prices paid for cattle the past two months, have

affected their value to the furthest limits of the Western grazing

country, and have revived an interest in the growth and feeding of

cattle which will be felt for a long time. Several large herds have

changed hands in Colorado, Montana and Wyoming lately at a handsome

profit to the original owners. A large amount of idle capital seeking a

safe and profitable investment will be put into stock this year all over

the West.4

In addition to high prices, McEachran reported heavy losses of stock

in the districts where the company had planned to purchase breeding

cattle, with a consequent effect on prices.5 Accordingly the

investment in cattle would have to be higher than had been planned

initially.

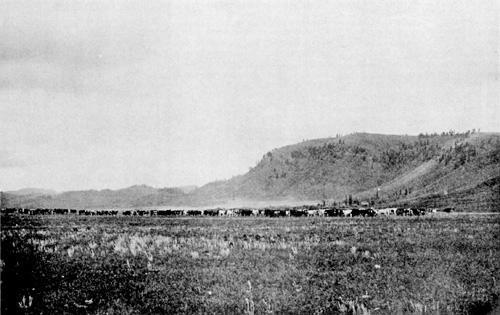

17 A herd of cattle west of Calgary, Cochrane

ranch, 1882 or 1883.

(Glenbow-Alberta Institute.)

|

The first purchase, 500 head from Walla Walla, Washington, was

supervised by Mose McDougall. The drive hack was a long and costly one

for McDougall was drowned in the Hell Gate River near Missoula, Montana.

Other purchases followed; Walker on one occasion bought 3,000 head when

he met some ranchers while waiting for a stage in Dillon,

Montana.6 Most of the cattle were purchased in Montana and

the main herd, numbering six or seven thousand, cost $16 a head

delivered at the boundary. The cattle were purchased from six different

outfits—I. G. Baker and Company, Harrison and Company, Pollard and

Baker, and the firms of McKenzie, Strong, and Price.7 They

were well chosen and within their limits they were big, fine animals,

well finished, well developed and carrying weight easily.

The cattle were to be delivered to the international boundary by the

vendors and from there I. G. Baker and Company undertook to deliver them

to Big Hill at $2.50 a head. The trek, which was to become a byword in

the Northwest for hard driving, was supervised by Howell Harris as far

as the border where Frank Strong, foreman for Baker's, took over. To

speed the proceedings up, Strong divided the herd in two, the steers in

the first batch and the cows and calves to follow. The pace was wicked,

the steers averaging 15 to 18 miles per day, the cows and calves close

to 14. The cowboys "tin-canned" and "slickered" them (kept them moving

by rattling tin cans and waving slickers) from morning to night without

a break and kept them so closely herded at dark that they had scarcely a

chance to graze, although in any case they were usually so tired that

they preferred resting to eating. This sort of pace taxed the steers to

the limit; its effect on the cows and calves was cruel. A number of

wagons trailed along in the van to pick up straggling calves, but they

were scarcely sufficient to save all those that fell behind. Too young,

weak and hungry to keep up with the grown stock, they dropped out, were

piled in the wagons when there was room, or left to die. Some calves

were traded off by the cowboys for a pound of butter, a drink of milk or

tea, or to whiskey traders who, to their considerable profit, accepted

calves as legal tender.8

Such a massive drive could not fail to attract notice even in

conditions of sparse settlement. Lachlan Kennedy, a Dominion land

surveyor, met 2,800 head near Fort Calgary on 2 September and a few

weeks later passed another herd of 1,800 further south at the Willow

Creek ford.9 The governor general, the Marquis of Lorne, also

encountered the herds during his tour of the Northwest. That part which

had already arrived in Calgary when his Excellency passed through was

drawn up for vice-regal inspection by Baynes and one of the foremen, Mr.

Barter. An exhibition of roping was put on by the cowboys, who were "all

armed to the teeth," and who impressed the party with their

skill.10 The governor general passed three separate herds and

though one must bear in mind the almost complete inexperience of the

expedition's chronicler, the Reverend James McGregor, a Scots

Presbyterian clergyman, plus the fact that he may have been reflecting a

discreet official point of view, it is recorded that the members of the

vice-regal party were impressed by the small death toll. This, of

course, is a direct contradiction of the version that has been passed

down to posterity. They travelled along the route taken by the drive for

some 300 miles, passing most of it in the process, and only occasionally

at distant intervals saw a carcase. Calves only a month old, claimed Mr.

McGregor, made their daily journey as well as their

mothers.11

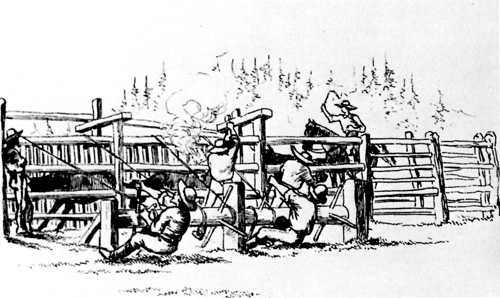

With the cattle at last on hand, the first thing to do was to brand

them. They could not be loosed on the range without brands and they had

to be turned onto the range to graze and gain strength before winter.

Time was short and there were thousands of cattle. The solution adopted

by the ranch management was to put on a "hair brand," one that was

simply scraped in the hair with a knife or with acid, and leave the

permanent branding until the spring round-up. This step was to lead to

considerable problems. (Later Walker devised a contrivance for branding

full grown cattle, a "squeezing gate," that was

an excellent idea but did not, unfortunately, always work

satisfactorily.12)

18 Round-up on the Cochrane ranch, showing Walker's "squeezing

gate."

(Canadian Illustrated News, Vol. 26, No. 22 (25 Nov.

1882), p. 340.)

|

In the meantime, there was much additional work. Sheds had to be

erected for the thoroughbred stock, both cattle and horses, and hay was

put up at different points to feed them.13 The stock from

Washington and Montana, being native, was expected to fend for itself on

the open range.

To date, $124,780.01 had been spent on cattle of which 6,799 head,

including 58 thoroughbred bulls, were on the ranch.14 At this

point, with nearly 7,000 head of exhausted stock and only enough winter

food for the thoroughbreds, winter closed in early and hard. The months

of unending cold and snow that followed gave the lie to all the

glittering expectations. There was no sign of those mild open winters during

which cattle fattened on the protein-rich grass cured on the stalk in

the fresh mountain air. The miserable starved animals, far from their

accustomed ranges, had no idea where the springs and grazing areas were

even if they could have reached them under the snow. Drifting ahead of

the winds, they gathered for shelter in the snow-filled coulees and

there they died by the hundreds of cold and starvation. To be fair to

the country the winter was probably not more severe than could have been

expected. Had the cattle been fit and accustomed to the range, they

probably would have borne out the expectations of the investors as to

the wintering capabilities of the Northwest cattle country. Such,

however, was not the case and losses were heavy, close to a thousand

head according to Walker.15

The Empire Grows

In Montreal, the senator and his colleagues were no doubt shaken, but

were evidently undeterred by the set-back. Nonetheless, they were all

good businessmen and the company began to take steps to hedge its bets.

The shareholders independently applied for certain choice grazing

leases bordering the Cochrane leases with the evident intent of

circumventing regulations and increasing the area available to the

Cochrane ranch.

In February 1882 Charles Carroll Colby applied to the Department of

the Interior for a grazing lease for a tract of land between the Belly

and Waterton rivers. On the seventeenth of that month the senator's

son-in-law, Baynes, applied for a lease of Townships 25 and 26 in Range

2, and half of Township 26 in Range 3, west of Calgary. On the

twenty-first, E. T. Brooks applied for a lease in the vicinity of

Colby's, south of Fort MacLeod.16 In addition, on 17

February Cochrane wrote the minister in connection with his

"understanding with the goverment that I should have on behalf

of the Cochrane Ranche Coy, the first claim of the lands required

by that Coy, for grazing purposes,"17 and submitted a

formal application for the required lands at Big Hill. Another

application of which original request has not survived was from A. W.

Ogilvie for a lease on the eastern border of the Cochrane ranch.

Under the authority of PC 722 of 11 April 1882, the requested grazing

leases were authorized and the accompanying map (see Fig. 10) indicates

just how well the senator marshalled the "Old Boy Network" of

Parliament Hill, the Eastern Townships and the Montreal financial

community. To the west of Calgary the Cochrane Ranche Company received

Ranch 42, consisting of 100,000 acres in that part north of the Elbow

River of Townships 24 and 25 in Range 3, Townships 25 and 26 in Range 4,

and the eastern halves of Townships 25 and 26. Just to the east, Ogilvie

received Ranch 43, consisting of 34,000 acres comprising that part north

of the Elbow River of Township 23, Township 24 and the southern half of

Township 25, all in Range 2. On the northeast borders of the Cochrane

ranch lease, Ranch 44 — 55,000 acres made up of the northern halves

of Township 25 and Township 26 in Range 2, and Township 26 in Range 3

— was leased to Major Baynes. These three leases made up a neat

block of 189,000 acres of choice grazing land along the Bow River west

of Calgary.

In the southern part of the province, under the name of the Eastern

Townships Ranche Company, Brooks was granted Ranch 34, consisting of

33,000 acres between the Belly and Waterton rivers in Townships 5 and 6,

Range 26, and Township 5, Range 27, all west of the fourth meridian.

Continuing on from the southern border of this lease. Colby, in the name

of the Rocky Mountain Cattle Company, received 73,500 acres, Range 25,

described as the land between the Belly River and the Waterton River and

its north fork, and the northern limit of Township One and extending

westward to the western limit of Range 29 W.4. These two leases made up

a neat package bounded almost entirely by natural frontiers of rivers or

mountains and totalling 106,500 acres.18 Colby was as

determined as Cochrane to get precisely what he wanted. The bother of

straightening out the borders of leases he found to be a nuisance and

once matters had been arranged between himself, Ogilvie, Brooks and

William Mitchell19 (later senator) of Drummondville, Quebec,

he requested of the Department of the Interior:

In order to avoid further annoyance and complication I beg

respectfully to request that you will be good enough to give immediate

instructions that no further applications be received upon any of the

lands mentioned in the enclosed memoranda and that the said lands be

included in the list of unopposed applications.20

If further evidence is needed of the close relationship between these

two ranching companies it need only be noted that the rent for the

Eastern Townships Ranche Company was paid in February 1883 not by

Brooks, the lessee, but by Colby.21

Influence

While this is not the place to discuss the subject in detail, it is

evident from the references made thus far, and even more so from a

detailed perusual of the relevant files, that influence, particularly

political influence, played an open and acknowledged part in the

granting of the grazing leases. Forty-six leases were authorized in

March 1882 and of those awarded to individuals, a number were

Conservative members of Parliament — A. T. H. Williams (killed on the

steamer Northwest during the Rebellion), D. O. Boudreau, Thomas

Temple, O. Ford Jones, and Alexander Shaw — as well as those

connected with the Cochrane project. Some, such as Lieutenant Colonel

Francis W. DeWinton, the governor general's secretary, had other

connections; those of no particular influence themselves found that

mountains became molehills with the aid of a friendly MP. In this last

situation was Strange whose difficulties dissolved when he obtained help

from W. T. Benson, MP, himself a cattle breeder, and Alexander Gunn, MP,

who though the Liberal who had personally defeated Macdonald in Kingston

in 1878, must have been privately a friend of the prime

minister.22 How much political influence could be found among

the directors of the various leases granted to corporate entities makes

for interesting speculation if the Cochrane Ranche Company is any guide.

Certainly the Allans of Montreal who formed the North-West Cattle

Company carried much political weight and so did Captain John Stewart of

the Stewart Ranche Company. It cannot be doubted that Macdonald

considered the granting of leases of tens of thousands of acres of land

as a useful way of paying off political debts or creating new political

obligations. The entire procedure was quite open and it must be assumed

that such opportunities as this were considered as part of the

perquisites of political life.

By the spring of 1882 Cochrane had acquired control, either himself

or though friends, of two of the finest ranching areas in the Northwest.

Most of the Bow River country between the government reserve

around Calgary and the Indian reserve at Morley was in his hands. Though

experience was to indicate that the area had its drawbacks, public

opinion considered it to be the prime grazing area of the whole

Northwest and for the senator to acquire virtually the entire block is

an indication of the influence he was able to bring to bear. The

southern block, controlled by Colby and Brooks, though isolated, was

obviously a choice area even then and was to become one of the finest

ranching locations in the country.

The First Round-Up

The Cochrane Ranche Company again ran into trouble during the spring

round-up in 1882 for the hair brands so hastily applied the previous

fall had virtually disappeared when the cattle shed their winter coats.

To ensure that the company suffered no greater loss than that already

endured, McEachran issued specific instructions to Walker to round up

every unbranded head on the range and put the Cochrane "C" on it.

Assistance was obtained from those settlers already in the vicinity,

many of whom were glad to help if only for the chance to socialize. Help

they did until they discovered to their dismay that when Walker received

an order he carried it out to the letter, in this case even if it meant

branding stock which, though identifiably belonging to someone else,

was nonetheless considered to be unbranded. The settlers quit in a body

and scattered across the range to the many hidden coulees and ravines

where in self-defense they began to appropriate calves and unbranded

cows and steers, most of which were probably Cochrane stock. A

respectable number of animals changed owners in this way. The settlers,

who declared that they would have been faced with ruin had they let the

big ranch proceed unchecked, acquired new stock while the Cochrane

ranch lost a number of cattle and acquired a harvest of ill-will among

the small holders that was a long time dying.23

Once the losses, about a thousand head, were known, it was possible

once again to set out on a buying trip both to continue building up the

herd and to replace the dead stock. Early in the spring, Walker went

down again to Montana and arranged for the purchase of four or five

thousand head from the large ranching outfit of Poindexter and Orr. He

was on the point of closing the deal when a wire from McEachran informed

him that arrangements had been completed to have I. G. Baker and Company

handle the purchase of stock. That company had decided to go into the

ranching business and it would be, it was considered, more profitable if

the cattle for the two firms were purchased together. On arrival at Fort

Benton on his return, Walker received a second wire which to his dismay

informed him that the deal with Baker's was off. Hastening back to

Poindexter and Orr's, a 300-mile journey, he was informed that in the

intervening weeks the price had risen. If he wished to buy the same herd

he would have to pay $25,000 more. That was enough for Walker. He paid

the price, but sent in his resignation to take effect as soon as a

replacement could be found, a process that was to last five months.

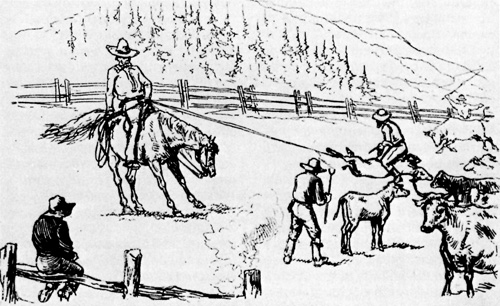

19 Round up on the Cochrane ranch.

(Canadian Illustrated News,

Vol. 26, No. 22 [25 Nov. 1882], p. 340.)

|

At that, the deal was not too bad for the contract, signed 16 May

1882, called for the purchase of the herd at $25 per head. Although this

was more than the $16 paid the previous year, it was the best they were

to do for some time for later in the summer they were paying T. C. Bates

and F. M. Good $45 per head, and Baker's $40 per head.24

Walker himself did well after he left the company. Obviously he had

little faith in the management of its affairs, for he withdrew his

investment as well as his services. A good businessman, he took out his

equity not in cash but in the form of a sawmill which he had persuaded

the company to build earlier. This proved a wise move, for Calgary was

already expanding rapidly and with the arrival of the railway the town

was to boom. Those who were in on the ground floor did well indeed.

The Second Drive

There still remained the task of transferring some thousands of

Poindexter and Orr cattle north to their new range on the Bow River. The

ensuing drive and its sequel proved to be a repeat of the previous year.

The herds were driven hard and reached Fish Creek just outside Calgary

in September only to be faced with a bitter snowstorm. Bad drifting

buried the trail and formed great banks blocking the weakened animals.

Poindexter offered to leave his cowboys for a month if Walker, whose

replacement had not yet arrived, would let the cattle stay where they

were for that time to recoup their strength, but Walker refused. He had

been ordered to get the cattle to the range as soon as possible and

insisted on Poindexter delivering them to Big Hill as the contract

specified. Accordingly, using some strong local steers to break trail,

the herd was driven to Big Hill where Poindexter is reputed to have said

"Here they are, I have carried out my contract and delivered at the Big

Hill. Count'em now because half of them will be dead

tomorrow!"25

The Second Winter

This was the welcome that greeted the new treasurer of the ranch,

Francis (Frank) White, who with an experienced cattleman from Virginia,

W. D. Kerfoot, was to take over from Walker. White was a capable

accountant who had worked with eastern railways, but he had no ranching

experience and was described at this initial stage in his new career as

"apparently a fish out of water."26 Although he caught on

quickly, White was to learn the business the hard way. Kerfoot, a member

of a good Virginian family, had drifted west and was hired by James

Cochrane in August at Fort Benton "to take charge of the cattle or

other stock."27

Apparently what the directors had in mind was White as a business

manager who would make sure that economy was the prime concern with

Kerfoot, the practical cattleman, answerable to him. The ranch was, it

is clear, a business proposition, not a hobby.

White arrived on the ranch on 17 September, the night one of the

first frosts of the season hit, and Kerfoot arrived at about the same

time. On 30 September it began to snow on the range, probably the same

storm that met the new cattle at Fish Creek. The next few weeks brought

miserable weather steady snow for over a week, then a combination of

snow, sleet and rain. By 8 October the trail to Calgary was blocked,

though two days later Browning and James Cochrane were able to get

through on their way east.28 The new herd, numbering 4,290

head, appeared on 19 October by which time the snow had stopped and been

succeeded by bitter cold. Unwilling to get caught again in the spring,

White began to brand the new stock on the twenty-fourth, but by the

twenty-ninth it had begun to snow again. By 1 November it was apparent

that the Cochrane Ranche Company was in for another bad winter.

Snowstorm still continues, cattle suffering badly from herding. 3

dead near house, others falling. Concluded to give up the idea of

branding and sent cattle down to feed. Killing weak ones for

Indians.29

The rest of the winter was another set-back for the Cochrane herds.

For some reason, inexplicable in that both Browning and James Cochrane

were at the ranch until October and had seen the condition of the ranges

with their own eyes, the order was given to keep the cattle within the

bounds of the Cochrane lease.30 All through the winter the

village of Calgary was treated to the sight of long strings of bawling

cattle walking downstream along the tops of the river banks heading

instinctively toward the still open grazing country to the south and

east. Always they were driven back to the frozen range. White spent a

good deal of the winter travelling around the grazing country trying to

buy feed and although he succeeded to a surprising extent, even writing

letters to Ottawa to pry local government supplies loose, it was not

enough.

Spring was late that year and when the snow finally disappeared in

June the herds had been decimated. The extent of the disaster had been

apparent long before this. Early in May Cochrane had observed that

The past winter has been a particularly severe one on Cattle and

the losses sustained by the Company from this cause have been so

enormous that if they were to become actually known to the public a very

serious blow would be dealt to stock raising in the north west and much

injury would result to the Western Country

generally.31

A month later the news was even worse,

Recent letters inform me that our losses are enormous, over three

thousand (3,000) head, but we hope that the past winter will prove to

have been an exceptional one, and that there may not be such another for

many years.32

Allowance must be made for the fact that Cochrane was still trying to

talk the government into selling him five per cent of the lease and had

an interest in crying poverty,33 but even given

overstatement, the directors had evidently had enough. They had probably

begun to realize this as soon as the bills for extra feed began to come

in from White and had no intention of waiting to see if another winter

would be as bad. On his way down to Fort Benton in April 1883 to

purchase enough cattle to permit the company to fulfill its contracts,

White met the post heading north for MacLeod and Calgary. Among the

letters was one from Browning advising him of the company's decision to

change the base of its cattle operations to the area between the

Waterton and Belly rivers, south of Fort MacLeod.34

Failure

Of the thousands of cattle imported from the United States, it has

been said that by the spring of 1883 something in the vicinity of 4,000

remained.35 This is probably exaggerated, but so devastated

were the herds that in order to preserve what was left as well as honour

the government contracts, it had been necessary for White to purchase

extra stock at Fort Benton. For this they would have to pay; one

quotation for 250 steers worked out to $65 a piece, $20 more than the

price considered extravagant the previous year.36 There was

no choice, however; from the herds around the ranch site only 90 steers

and 20 barren cows could be found to fill the Indian department

commitments.37

At the beginning of May the plans were drawn up for the last

round-up, at which time Kerfoot accepted the position of manager at Big

Hill — for $2,500 a year and a house — while White moved down

to manage the southern range. White, however, continued to act as

treasurer until a new man, A. F. Cross, was appointed in the spring of

1884. At the round-up the cattle were divided into two herds; the first

moved out on 7 July, the second shortly afterward.38 One day

in July 1885, while doing the laundry beside Fish Creek, two girls of an

English family recently settled in the area became conscious of an

approaching deep rumble and in a few minutes a great herd of cattle

appeared coming over and down the bank of the other side of the stream.

The girls fled as the cattle forded the creek and passed on. When the

dust settled, clothes, washboards, everything but a battered tub had

disappeared.39 And so disappeared the great herds of cattle

from the Cochrane ranch.

The degree to which the failure of the Cochrane ranch affected the

Bow River district is witnessed by the fact that it was not until after

the turn of the century that the cattle population in the area exceeded

that of late 1882.40

A number of factors should be considered in assessing responsibility

for the ranch's failure. At this time the winters were harder than

usual, but it was unfortunate for Cochrane's reputation that other

cattle owners in the area suffered no more than the usual losses

attendant upon any industry dependent on the vagaries of

nature.41 It is only fair to note here that the suggestion

has been made that the small ranchers who were the other occupants of

the area were located in more rugged country and that the deep ravines

of this area, the Wildcat Hills, provided excellent shelter while the

hilltops were blown bare enough to allow cattle to graze.42

One can fault Walker for too rigid adherence to his orders when his

extensive western experience must have warned him that there would be

difficulties. A little flexibility on his part might have worked

wonders. And one must attribute part of the problem to the troubles

inevitable in any pioneer operation. The process of sorting out facts

from the hyperbole of the publicity about the northwestern grazing lands

was bound to be painful.

Nevertheless, Cochrane must be blamed for the failure of the ranch on

the Bow River. His unbounded determination, self-confidence and optimism

would finally make the Cochrane ranch an outstanding success on its new

southern range, both from the point of view of the investor and of the

cattle breeder, but led him to minimize the very real difficulties any

pioneer operation must face. His interest arose out of the enthusiastic

observations of surveyors and explorers which, however sincere, were not

based on a solid foundation of long experience in the area. He had

preferred their opinion to the opinions of old-timers such as "Kootenai"

Brown, a long-time resident of the foothills. Brown had met the senator

out on the range during an early scouting trip the latter was making to

locate suitable grazing land. Enthusiastically Cochrane told Brown,

"We're going to bring in several thousand head of cattle here. They

ought to live where buffalo lived and we should not need to feed them

hay in a mild climate like this where you have so little snow." Brown

warned him that this was not neccessarily true; that buffalo, like

sheep, ate grass right to the roots and then, having eaten a range

down, moved on, travelling thousands of miles in a season. Buffalo, he

went on, stood into a storm whereas cattle would drift with the wind

regardless of where it might lead. Finally, he advised cutting hay for

the winter, but to no avail for Cochrane only laughed.43

The prevailing simplistic belief was that once one had brought in the

necessary cattle, land and climate had combined to such a favourable

extent that one need do no more than guide the fat beeves toward the

waiting railway cars at marketing time. If in fact the Cochrane outfit

really believed, as its spokesman informed the Marquis of Lorne, that

the entire vast herd would require so little supervision as to need only

20 hands, then disaster was inevitable.44

A major error, and one made not only by Cochrane, was the acceptance

of the free-ranging system within the limits of the lease. As the name

implies, the cattle were allowed to wander where they wished within the

boundaries of the lease and naturally gravitated toward the best ranges.

Consequently these were eaten down in short order, leaving only

second-rate grasses for the difficult winter months.

One can fault Cochrane for trying to direct too closely a new

enterprise in an unfamiliar environment from half a continent away as well as

for the type of direction. At times too much dependence was placed on

eastern techniques — cattle at Hillhurst did not wander freely

over the entire countryside in winter so they were not allowed to cross

the lease boundaries at Big Hill and had to feed on the second-rate

grasses left after unmanaged summer grazing. At other times not enough

dependence was placed on eastern techniques — although the grass

did cure on the stalk and Chinooks often kept the snow cover to a

minimum, hay was also required.

In short, it would seem that all the attractive aspects of the

Northwest, no matter how they differed from conditions in the East, were

accepted with an open mind, but the possible drawbacks, particularly

those which involved spending money, were not acknowledged.

Most contemporary opinion blamed Cochrane. Macdonald averred that

"his loss of cattle is mainly attributable to his want of management

caused by his parsimony, more so than by the coldness of the

climate."45 The Honourable D. L. Macpherson said that

I am persuaded that it was mainly owing to the rapid and

injudicious manner in which the cattle were driven into the country that

the losses of last winter occurred. The cattle had not time to regain

their strength before the winter was upon them, and it being unusually

severe, the mortality among them was consequently

great.46

While both Macpherson and Macdonald might be forgiven if they were

reluctant to admit that in the Northwest they might after all have drawn

a bad hand, their opinions were supported by others less likely to be

biased. One of these, Moreton Frewen, observed later that "it was their

fault rather than their misfortune — The wonder was handling their

herd the way [they] did, that they did not lose the whole."47

Alexander Burgess, deputy minister of the Interior, was rather more

tactful, but worried about the effect of so many carcases of Cochrane's

cattle on the sensitive eye of the land hunter.48

It is to the senator's credit that once the hard lessons were learned

on the Bow River, new methods were applied on the southern range. All

ranchers had realized that it was simply not enough to turn the cattle

loose on the ranges and expect them to go forth and multiply. This was

made abundantly clear by the disastrous winter of 1886-87 wherein

it became apparent that heavy stock losses were not the sole province

of the Cochrane ranch. In the latter part of the 1880s it became

increasingly common to put up at least enough hay to feed all the calves

over the winter, to erect shelters at strategic points and to yard the

cows about to calve. These steps had an impressive effect on the rate of

increase and the industry began to approximate the predictions made for

it at the beginning of the decade.

|