|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 16

The Cochrane Ranch

by William Naftel

Introduction

What is now the southwestern corner of the province of Alberta is

grazing country. The foothill grazing lands form the boundary between

the Alberta plateau and the Canadian Cordillera, or Rocky Mountains. The

terrain is rough, split by draws and coulees carrying the streams that

originate in the mountains. The elevation of the ranges varies

considerably from 3,000 feet in the east to 4,500 feet in the west.

It is no coincidence that the grazing area coincides with the

effective limits of the area subject to Chinook winds. These warm, dry

winter winds are a phenomenon the extent of whose geographic penetration

defines the grazing corridor as much as the availability of superb

grasses and good water. The effect of the winds is such that the snow is

melted, the grass is revealed and cattle can (in theory) range as freely

in winter as in summer. Sometimes, however, the Chinooks do not

come.

Along with the Chinooks was an other fortunate natural coincidence

— the rich native grasses which thrive in the summer cure on the

stalk, producing a natural hay. "They thus preserve all their nutritious

qualities, and made excellent feed for the winter, a fact which is

proved by the fat condition of all stock wintered in that

country."1 The attractive qualities of the grasses result

from the soil minerals which produce a plant rich in proteins and the

dry winds of late summer that dessicate them while they are still on the

stalk. The types of grasses found vary according to altitude and

rainfall. On the lower levels are blue gama, spear grass, western wheat

grass, June grass and Sandberk's blue grass. Porcupine grasses and wheat

grasses begin to predominate as the true prairie is approached and on

the higher levels, foothill species such as the fescue, oat grasses, and

again, wheat grasses, predominate.

The region most suitable for grazing, at least in the eyes of

experienced farmers from the East, was considered to run "from the

boundary line north to Morleyville, including the belt of land extending

from twenty-five to thirty miles east of the Rocky

Mountains."2

It is a lush and beautiful country — green rolling hills covered

in knee-high grasses and watered by abundant streams, rivers and springs

which burst forth from the slopes in profusion. Presiding over all, the

frosted peaks of the Rockies glitter in the sun of a clear day, their

serried ranks disappearing over the distant horizons to the north and

south. Small wonder the early observers rhapsodized over the district,

but these men were but passing travellers whose explorations and

observations were limited to the summer months. The solid Scotsmen who

manned the Hudson's Bay Company forts throughout the Northwest learned

early that the foothill Indians did not want them. The Blackfoot, the

fiercest of all the Plains nations, refused to allow traders into their

territory and the Hudson's Bay Company had to be content with posts on

the fringes, such as at Rocky Mountain House and Fort Edmonton.

Accordingly, there was little of the careful observation and long

experience by fur traders that paved the way for the settler in other

corners of the Northwest. There was no one to temper the largely

justifiable enthusiasm of the itinerant observers with words of caution,

no one to note that on the rare occasions when the Chinooks did not

blow, winter in the Bow Valley could be as long and as hard as in the

Red River Valley.

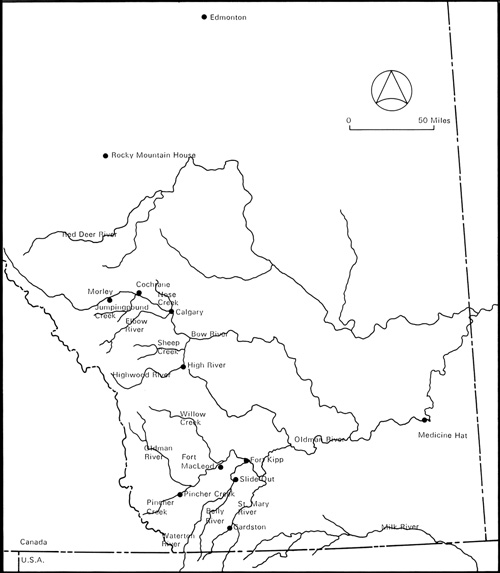

1 Map of southern Alberta, showing sites mentioned in the text.

(Map by S. Epps.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

The suitability of the foothills for cattle raising had been known

since the first detachments of the North West Mounted Police penetrated

the area in 1874 and attempts were made at that time to develop a

ranching industry. The first appearance of cattle on the foothill ranges

came shortly after the establishment of the Mounted Police at Fort

MacLeod gave some assurance of law and order. Hoping to acquire

government contracts, Joe McFarland and Henry Olsen arrived from Montana

in 1875 with a herd of dairy cattle and located a few miles downriver

from the fort. In the fall of 1874 a man named Shaw drove 500 beef

cattle across the mountains from British Columbia where ranching had

flourished in the interior since gold-rush days. Although en route to

Fort Edmonton, Shaw paused at the Methodist mission at Morley on the Bow

River where he remained at the urging of the Reverend John McDougall,

not just over the winter but for an entire year, the cattle surviving in

good health.3

Other herds were brought in from Montana in the 1870s with some

success so far as the welfare of the cattle was concerned. It would

appear that these pioneer cattlemen were less fortunate financially for

three main reasons: lack of markets, Indian raids, and lack of official

encouragement.

The major part of the market was the North-West Mounted Police

detachments and contracts for their supply were held by the active and

enterprising firm of I.G. Baker and Company of Fort Benton, Montana.

While this firm was willing to buy all the beef locally available, the

growth potential of the market was clearly limited, particularly in view

of the announced intention of the government to cut, rather than

increase, the strength of the force. There was no Canadian market nearer

than Georgian Bay and the American ranching industry was unlikely to

allow the passage of Canadian cattle across the border unchallenged. No

other markets existed.

Another limiting factor began to develop toward the close of the

decade. The decline of the buffalo was initially greeted with enthusiasm

by ranchers for cattle were attracted to the migrating herds and

disappeared more completely than any rustler could hide them. With the

disappearance of the buffalo, however, a new problem arose. With their

staple food gone, the Plains Indians for the first time were faced with

large-scale starvation and such cattle as were on the prairies offered a

temptation too often impossible to resist. In fact, it would appear that

there was not as much cattle stealing as the often desperate condition

of the Indians might have warranted, but the stockmen tended to place

the blame for any dead or missing cattle on the Indians. Whether the

responsibility lay with the Indians or not, losses were high enough to

be discouraging and played a part in inhibiting the early development of

the industry.

Associated with this factor was the attitude of the Mounted Police

which was not particularly favourable to the cattlemen, being founded on

the entirely justifiable belief that the Alberta country was not yet

ready for settlement. As late as 1882 the commissioner of the force was

to write concerning the Blackfoot tribes whose territory this was:

This powerful tribe... has but recently come into contact with white

men, and their experience of them is almost altogether of the Police

Force. They are as yet perfect savages able to mount at least 1000

warriors, exceptionally well armed and equipped.4

By 1882 other observers were more impressed by the decline of Indian

power, but undoubtedly the description would have rung true for the

pre-1880 period. The influence of the Mounted Police with the Indians

rested on prestige rather than strength, hence they were unwilling to

precipitate disputes over stolen cattle or to treat them as some

stockmen, with American precedent in mind, suggested. The police were

generally of the opinion that those who brought cattle into a frontier

area must be willing to accept the consequent losses.5

Accordingly, by 1879 the first attempt to introduce ranching to the

Northwest had petered out with the return to the United States of a

number of stockmen who had come up from the ranges of Montana to make a

new start.6

The National Policy of the Conservative Party which led to Sir John

A. Macdonald's return to power in 1878 had in it more than the creation

of an eastern manufacturing complex. Its most important components for

the future were those which promoted a transcontinental railway and the

settlement of the Northwest, both designed to secure for the young

Dominion the vast, empty territories acquired in 1869 from the Hudson's

Bay Company. It was easy to build the railway: simply supply enough

capital and it would be done. To fill the West with settlers, however,

was another matter. Thousands of people must be persuaded to move to a

new and quite unknown land. Such a vast migration would, under the best

circumstances, take time; meanwhile the rolling prairies lay empty,

inhabited only by dwindling herds of buffalo, some few thousand Plains

Indians and a scattering of itinerant and discontented Métis.

It lay empty, but not unnoticed. Apart from the desire to colonize

characteristic of 19th-century western nations, there lurked below the

southern horizon the dark shadow of Manifest Destiny. By the end of the

1870s, American expansionism was more subtle than it had been even a

decade earlier; nonetheless, twisting the Lion's tail was still a

permanent feature of Fourth of July rhetoric. Much of the oratory was

simply that — rhetoric — but in the American Midwest the

message was still eagerly digested by election audiences. There the

available supply of new homesteads was begining to run out, but the

desire for land was as strong as ever. To the north lay the virgin

prairies of the Canadian Northwest and it was easy to translate simple

land hunger into a desire to extend to this empty territory the benefits

of a governmental system which made full use of such resources. While at

this point it was fairly clear that the United States government would

not resort to military means to extend its domains, it was obvious that

considerable pressures were being exerted which made it equally certain

that, short of war, that government would do all it could to obtain the

Canadian West. It was, therefore, imperative that the Northwest be

occupied by Canadians, on the assumption that possession is nine points

of the law.

Once the contract to construct the Canadian Pacific Railway had been

let and the line built, settlement, it was expected, would eventually

take care of itself. Even with the best of luck, however, this would

take some time and in the interim it was deemed necessary to take some

action to hold the western end of the prairie as settlement moved

westward along the railway line. A western ranching industry, eminently

successful in the United States, might provide the means to occupy a

potentially vulnerable and certainly empty region.

A more immediate reason for the encouragement of such a programme

also existed. In line with the aims of the National Policy there was no

reason why the Canadian livestock industry, as well as the manufacturing

industry, should not be encouraged. The more of the domestic demand that

could be supplied the better and, as eastern breeders were showing, a

profitable market in England awaited those prepared to supply a high

quality product.

Another important consideration was the need to develop through

traffic on the CPR in order to justify the enormous construction costs.

This was particularly true of the expensive sections north of Lake

Superior where local traffic would be nonexistent. A thriving cattle

trade between the Rocky Mountains and the Montreal stockyards would

prove a valuable addition to the balance sheet.

That beef was the mainstay of the foothills economy within two years

of the collapse in 1879 of the initial ranching attempts there is

directly attributable to the actions of the new Conservative

administration. First, on 21 October 1880, a contract was signed with a

Montreal consortium for the construction of the CPR. Secondly, the

government had, as a means of encouraging settlement, begun to press on

in earnest with the surveys of the Northwest and thirdly, was now

insisting that the Indians settle themselves on their designated

reserves.

All three of these objectives were attained with a surprising degree

of efficiency (in view of the concurrent mishandling of the Métis

problem). The completion of the CPR well within its allotted term is a

familiar story. The surveys were models of precision and accuracy that

have dismayed generations of lawyers who have elsewhere found inaccurate

surveys sources of endless, profitable litigation. Through a combination

of tact and firmness the Indians had been nearly all settled on reserves

by 1881-82 where, even during the 1885 Rebellion, they remained quiet

with but few exceptions.

With the railway under contract and the prospect of a reliable system

of land tenure free from harassment by Indians, the Northwest lay open

for exploitation.

In the context of the times, however, to most people the former

Hudson's Bay Company territories, with the possible exception of the Red

River settlement, were a remote and inaccessible region peopled by

savage Indians and rebellious Metis. The parliamentary debates at the

time of the granting of the CPR contract reveal that a large and

influential segment of Canadian opinion saw the Northwest as an asset to

be sure, but one whose exploitation might best be left to future

generations who could more easily bear the cost. Even the many convinced

exponents of the virtues of the new territories believed that

development hinged on the success of a Pacific railway which could take

years to complete.

Nevertheless, in 1881 the Cochrane Ranche Company Limited, inspired

by Senator Matthew Henry Cochrane, industrialist and cattle-breeder,

made Big Hill, now Cochrane, Alberta, the centre of Canada's first major

venture into the ranching industry. With the hearty encouragement of the

Dominion government, Cochrane and his fellow investors sank tens of

thousands of dollars into the ranch, but after two years of

overconfidence, hard winters and managerial rigidity, the ranch was

forced to move its cattle further south to a more equable climate closer

to the border, leaving the Big Hill site to the British American Ranche

Company, a corporate cousin dealing in horses and sheep.

One might well question what significance an apparent failure might

have, but in fact its impact was considerable, centring on its position

as the pioneer large-scale ranching operation in the Canadian West and

on the personality of its founder, Senator Cochrane. His decision to

take the first step was an influential one. In exercising his widely

respected judgement, Cochrane gave practical support to the opening of

the West by influencing fellow members of the eastern financial

community to invest in the Cochrane ranch and in the grazing country.

(Although his fellow investors obtained their own leases at about the

same time as Cochrane, most of their ranches were not operating for a

year or two.) A waiting crowd watched his errors, saw the CPR become a

reality, and at the first opportunity launched a score of other ranches.

In so doing, however, they had to fit themselves into the ranching

legislation hammered out between Cochrane and the Department of the

Interior to accommodate the requirements of the Cochrane Ranche Company.

It was under this legislation, lasting scarcely a decade, that the first

wave of organized settlement was introduced into the far West.

The following two chapters will summarize government grazing, import

and quarantine regulations affecting the Canadian ranching industry and

discuss the capitalists involved in the Cochrane ranch. Subsequent

chapters will trace the establishment and decline of the Cochrane ranch

at Big Hill, its transfer to more southern ranges, and the activities of

the Cochrane ranch's successor and corporate cousin at Big Hill, the

British American Ranche Company.

|